Online reputation is nowadays particularly significant in the context of hotel firms due to the high sensitivity and enormous influence of electronic word-of-mouth activities of customers. Since there is still no clear set of online reputation-generating factors, the aim of this paper is to contribute to this knowledge considering the role of family governance as an antecedent of hotel online reputation. Specifically, our purpose is to explain whether the heterogeneity among family firms regarding their family influence on the business exerts a significant effect on online reputation of hotel firms, investigating how family ownership and family management dimensions interact in terms of influencing online reputation. Our findings, based on a sample of 157 Spanish family hotels, indicate a positive influence of family ownership on a hotel's online reputation, augmented by a positive moderating effect of the family management represented by the presence of a family CEO managing the hotel.

Fombrun (1996:72) defined a firm's reputation as ‘a perceptual representation of a company's past actions and future prospects that describes the firm's overall appeal to all of its key constituents when compared to other leading rivals’. Literature has usually shown that a favourable reputation is beneficial to a firm, being a valuable resource positively related to customers’ behaviour intentions (Tat Keh and Xie, 2009) that leads to better firm performance (Roberts and Dowling, 2002). However, with the advent of the Internet and the customers’ improvement of accessing to information, the current notion of firm reputation has evolved and expanded towards the so-called online reputation (Bakos and Dellarocas, 2011). The online reputation is especially important in the hospitality industry and, particularly significant in the context of hotel firms, considering the high sensitivity and enormous influence of electronic word-of-mouth activities of customer on a hotel's online reputation (Cantallops and Salvi, 2014; Melián-González et al., 2013).

The review of literature regarding a hotel online reputation can be divided into studies examining organizational consequences of online reviews and those analysing antecedents that influence customers to write online reviews. In the first stream (consequences), there are abundant studies pointing out how a favourable hotel online reputation through the online assessments of customers positively influence on firm sales and performance as well as on customers’ attitudes towards the firm (Qiang et al., 2009; Sparks and Browning, 2011). Similarly, in the second stream (antecedents), researches have focused, on the one hand, on customer background's factors such as satisfaction, failure and recovery or sense of community belonging (Bronner and Hoog, 2011; Crotts et al., 2009; Nusair et al., 2011; Swanson and Hsu, 2009) and, on the other hand, on organizational characteristics such as firm's image, innovation, quality of product and services, and governance features (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Inversini et al., 2010; Morrison et al., 2010), as some main causes of a favourable or unfavourable hotel online reputation.

In terms of organizational governance antecedents, one of the most relevant factor influencing hotel online reputation is related to family involvement (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Morrison et al., 2010). However, and despite a number of works focusing in some adjacent treatments (Kong, 2013; Paek, 2012; Peters and Kallmuenzer, 2015; Sampaio et al., 2012; Singal, 2014), this topic is unexplored to date. Since organizational governance issues determine an essential part of firm's abilities and intentions (Mishina et al., 2012), it is expected that the presence of the family in the ownership and/or the management of hotels strongly influence resources and capabilities, goals and behavioural intentions, all of which may have a significant influence on their online reputation (Chrisman et al., 2012; Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013).

Considering this gap in the literature, and on the basis of the combined arguments proposed by the familiness view (Habbershon and Williams, 1999; Habbershon et al., 2003), the organizational identity theory in the context of family firms (Dyer and Whetten, 2006; Scott and Lane, 2000; Zellweger et al., 2013) and the socioemotional wealth (SEW) theory (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007, 2011), the aim of this paper is to analyze the influence of family involvement on a firm's online reputation over a sample of 157 Spanish family hotels. Looking for heterogeneities among family firms (Chua et al., 2012; Chrisman et al., 2012) in this matter, we specifically investigate on the interaction between the two main dimensions characterizing family influence in the business – ownership and management dimensions – in order to explain how they influence and interact in terms of hotel online reputation.

This study contributes in several specific ways to this line of research. First, our investigation is one of the first attempts to examine whether the presence of the family in the business impacts on the reputation of hotels, considering that hotels are companies belonging to a sector usually characterized by a very high presence of family businesses (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Merino et al., 2015; Morrison, 2002). Second, we look in greater depth into the role of a specific reputation dimension, the so-called online reputation, based on the assessment provided by customers, which is a form of reputation increasingly important for hotels, an industry where a favourable electronic word-of-mouth reputation is vital for competitiveness (Duan et al., 2008; Melián-González et al., 2013). Third, basing on several sources of theories, measures and methodologies, our paper entails an integral analysis of the family influence – that include ownership and management – allowing a global examination of how family governance heterogeneity affects online reputation among family hotels (Chua et al., 2012; Michiels et al., 2013). And fourth, our paper shows new evidence regarding the Spanish hotel context, one of the world's most prominent hospitality industry – holding the second position in world tourism, in terms of both number of travellers (after France) and revenues (after USA) (Pereira-Moliner et al., 2010) – and very well representative of typical family firms – with a concentrated shareholder base as well as a high proportion of family members active in management (Merino et al., 2015; Sánchez-Marín et al., 2016), which can be a particularly appropriate context for studying the influence of family on hotel reputation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. After a review of relevant research about online reputation in hospitality industry, we then explain the theoretical framework used to develop two hypotheses based on the particularities of family governance in terms of firm online reputation. Next, we describe our methodology, including sample description, variables measurement and statistical analyses. Then we present our results to, finally, elaborate on the discussion and main contributions of this study.

The role of online reputation in the hotel industryThere has been past hotel industry literature examining both antecedents and effects of corporate reputation in order to have a well-rounded understanding of this concept (Tat Keh and Xie, 2009). Basically, regarding online reputation consequences, researchers agree with the idea that because online comment is an important factor when choosing a hotel, a favourable online reputation positively affects the sustainability of a competitive advantage (Levy et al., 2013). Greater visibility on the web or positive online opinions lead to hotels achieving higher occupancy levels and room reservations (Qiang et al., 2009), improvements on their confidence perception (Papathanassis and Knolle, 2011), and increases in sales and performance (Ye et al., 2009).

Concerning the antecedents, prior research on the hospitality industry has found some factors motivating the generation of electronic word-of-mouth, a proxy of online reputation (Cantallops and Salvi, 2014). Aspects related to the customer background perceptions such as customer satisfaction and dissatisfaction levels, failure and recovery capacities, sense of community belonging and social identity, pre-purchase expectations and customers’ delight, have been identified as main motivations for writing reviews (Bronner and Hoog, 2011; Casaló et al., 2015; Crotts et al., 2009; Nusair et al., 2011; Swanson and Hsu, 2009). From the viewpoint of organizational characteristics, literature has mainly focuses on factors related to firm's image and commitment, capacity of innovation, quality of product and services, level of past performance, corporate social responsibility practices and governance characteristics (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Inversini et al., 2010; Mishina et al., 2012; Morrison et al., 2010; Ye et al., 2009).

In that vein, one of the least explored organizational factors influencing hotel online reputation is related to the governance characteristics of family firms (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Morrison et al., 2010). Despite some recent articles on hospitality industry have investigated how family ownership and management affects social responsibility programmes (Singal, 2014), entrepreneurial spirit (Peters and Kallmuenzer, 2015), organizational climate (Kong, 2013; Paek, 2012) and employee satisfaction (Sampaio et al., 2012), the influence on online reputation remains untested to date. Since governance determines firm's abilities and intentions (Mishina et al., 2012), it might expect that the involvement of the family in the governance – ownership and management – of the hotel strongly influences resources orientations and behavioural purposes that affect firm online reputation (Chrisman et al., 2012).

Thus, our research is positioned in the former lines, analysing the impact of family involvement in ownership and management on a hotel's online reputation. We develop these relationships below.

Theoretical framework and hypothesesThe influence of the family in a firm's reputation can be mainly explained by three main theoretical frameworks. Firstly, the familiness view, based on the peculiarities of family firm's resource and capabilities (Habbershon and Williams, 1999; Habbershon et al., 2003), proposes that family firms are more reputed due to the more trustworthiness long-term relationships established among the family firm and the clients and the rest of stakeholders (Huybrechts et al., 2011). Secondly, organizational identity theory in the context of family firms (Scott and Lane, 2000; Zellweger et al., 2013) suggests that the higher influence on the identity between the family and the firm the greater is the family's concern for reputation (Dyer and Whetten, 2006; Zellweger et al., 2013). And thirdly, both factors in family firms emphasized the pursuit of a favourable reputation, which provides an outcome that affords affective value to family members in terms of SEW preservation and family goals (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007).

Common measures of family involvement include the level of family firm ownership and the family presence in management (Chrisman et al., 2012; Villalonga and Amit, 2006). Accordingly, we use both dimensions, family ownership (in hypothesis 1) and family management (in hypothesis 2), to develop arguments explaining the power of families to pursue a favourable online reputation.

Family ownership and online reputationFocusing on family ownership, four main arguments lead us to highlight a positive influence of family control on a firm's online reputation. Our first argument relies on the familiness view of resources and capabilities of family firms (Habbershon and Williams, 1999; Habbershon et al., 2003) indicating that, overall, family firms have a more reliable reputation. According to Aronoff and Ward (1995), family firms are perceived as more trustworthy than others because customers often know the owners as well as the family members active in the business. Then, family-owned firms can cultivate a long-term relationship and generate trust with customers that can improve the family firm reputation (Huybrechts et al., 2011). Positive customer perceptions of family control and relationship-based business interactions within and between organizations create stakeholder efficiencies, enhancing the reputation of family firm (Aronoff and Ward, 1995). The family's reputation and relationships with suppliers, customers, and other external stakeholders are reportedly stronger and more value laden as the family control, via ownership, increase (Habbershon and Williams, 1999). Furthermore, the association of the family with the products and services offered by the company can provide motivation to maintain and improve its quality, which will likely lead to an even greater degree of trust and better reputation (Huybrechts et al., 2011).

Secondly, and connected to the fore-mentioned idea, a firm with a strong presence of the family in its ownership may be more interested in augmenting family reputation via the business due to a closer identification with the firm (Dyer and Whetten, 2006). Family visibility is especially prominent in concentrated-owned family companies, which often advertise their family roots and association as “a family company” (Miller et al., 2013). In that vein, it is common for such firms to have family members serving as visible executive figureheads. Having the family name associated to the firm can be a powerful incentive to improve reputation. As a negative reputation would be detrimental for the family firm, and family members involved in the family firm are associated to this name, they might well make great efforts to uphold it (Dyer and Whetten, 2006). Indeed, several authors indicate that many family owners are convinced that the sustainability not only of themselves but of their subsequent generations relies on the generally acceptable conduct and reputation of the business (Miller et al., 2013). Thus family businesses have a strong incentive to ensure the long-term success and vitality of their firms, consistent with a long-term orientation and concern for firm reputation (Singal, 2014).

Thirdly, and linked to the previous argument, the intensified identification of the family with the firm motivates family owners to pursue a favourable reputation for its contribution to the preservation of family's socioemotional wealth (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). Family firms exhibit a heightened concern for reputation and a strong inclination to pursue nonfinancial goals, ultimately protecting the family's own socioemotional endowments (Zellweger et al., 2013), even at the expense of harming their financial returns (Berrone et al., 2012). By doing this, concentrated family ownership gives family members the power to monitor the firm, to select board and management members and to enact policies that protect or enhance family wealth objectives, orientating the decision making to pursue a favourable reputation (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013). Thus greater family control should be related to greater power to pursue and protect a favourable reputation as a part of the family's socioemotional wealth.

And finally, because the family is usually the principal owner, family firms are sometimes said to have a reputation of being less risky to do business with, as failure would have a high personal cost (Schulze et al., 2003). The high ownership that controlling owners have might result in high personal endangerment in family businesses. Gomez-Mejia et al. (2007) suggest that family firms will also accept a higher risk of lower financial performance in order to maintain family control, adopting less risky strategic decisions. Because of the less diversified portfolio of family owners, they do not want to risk their socioemotional wealth, the future of the next generations, their name, and the reputation of their own family (Berrone et al., 2012; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Since the possibility of failure in the context of hotel industry is one of the most important concerns for customers in hospitality industry (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Singal, 2014) as well as for suppliers and banks, they may perceive family firms, as the proportion of family ownership increases, to be more trusted and then, more reputed (Huybrechts et al., 2011).

We can complement these arguments by those concerning the particular context of the hotel industry. In that regard, some studies find that hotels with family ownership invest more in social responsibility programmes (Singal, 2014), adding additional dimension to creativity, entrepreneurial spirit (Peters and Kallmuenzer, 2015), business enthusiasm and emotional/physical closeness with customer (Getz and Carlsen, 2005; Morrison, 2002) that potentially can have a positive impact on a hotel's online reputation. Considering all the above, we formulated our first hypothesis in the following terms:H1 There is a positive relationship between family ownership and firm's online reputation: the more ownership in the hands of the family, the more favourable online reputation.

Whereas all family firms are at least partly owned by families, only some of them are managed by family members. Typically, this management takes the form of a founder or family descendent who acts as the CEO (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006), the figurehead we focus as representative of the family management dimension. Considering that the CEO has enough discretion to make major decisions without undue interference from other family members or owners (Cruz et al., 2010; Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006), the fact that this CEO belongs or not to the controlling family will likely moderate the relationship between family ownership and a firm's online reputation (previously developed in hypothesis 1).

Entering in specific arguments, first, literature highlights that having a firm's CEO as a member of the controlling family embodies one of the major socioemotional wealth preserving mechanisms (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). The achievement of socioemotional wealth includes several specific objectives, among which reputation stands out. Sustaining firm reputation is associated with the favourable family image and the social capital building (Berrone et al., 2012). Compared to non-family CEOs, family CEOs are part of and will remain (emotionally) attached to the firm, are more identified with the firm (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013), developing and maintaining trusting relationships with suppliers, customers, and support organizations (e.g., banks and financial institutions), as well as building closer ties with the local community (Zellweger et al., 2013). Family CEOs are driven by more than economic self-interest, wishing to make a significant contribution to their organizations’ mission, longevity, and stakeholders (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006) and, finally, investing to strengthen their reputation (Ward, 2004). In addition, family CEOs whose names are on the business and whose past, present, and future are tied to the reputation of their firm may act as especially solicitous stewards, manifesting in lifelong commitment to the firm and competent management of resources and investments (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006). Because the family name and fortune are at stake, and because they will be there for the long term, family managers may focus on specific efforts to promote and benefit a favourable firm reputation (Craig et al., 2008; Huybrechts et al., 2011). Family CEOs’ concerns for the image and reputation of family make them more reluctant to infringe codes of conducts and violate moral codes (Dyer and Whetten, 2006), conducting them to be a trustworthy partner, pursue environmental actions and conform to social and institutional norms (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006).

Secondly, high family control provides family CEOs a feeling of employment security and a real buffer against unexpected (negative) firm performance (Cruz et al., 2010). Compared to non-family CEO, a family CEO is less likely to be susceptible to threatening moves by other parties (for instance, non-family outside directors or external investors) when family ownership is larger (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). Then the non-family CEO is more likely to be focused on more utilitarian and financial objectives – to respond to family and non-family shareholders’ expectations – than his or her family counterpart will be, so the psychological contract should be more protective and socioemotional-oriented for the latter than for the former (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007). Accordingly, stronger family involvement increases a family CEO's disposition and discretion to pursue non-financial objectives related to the preservation of family's socioemotional wealth, within which highlight a favourable firm reputation.

And thirdly, the continuity of family firms – provided by the long CEO tenure and family successions – may positively influence the personal reputation of family businesses (Huybrechts et al., 2011). It is commonly found that the average family CEOs tenure is longer than those of non-family CEOs (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011; Ward, 2004). Whereas non-family CEOs might see their job as a short-term objective, family CEOs are more likely to view their position as a long-term commitment so it would be more important for them to make sure that the family firm has a positive reputation (Aronoff and Ward, 1995). Bearing that in mind, some studies reveal that family CEOs, having spent considerable time in their jobs, try to prove themselves qualified for their positions enhancing reputation leading to a way of enduring several future family generations (Steier, 2001).

Furthermore, these arguments can be reinforced with several specifics from the hotel industry literature that have also highlighted some positive implications derived from the existence of a family CEO. To this end, some studies show that family CEO contributes to one of the dimensions of reputation, say labour environment (Paek, 2012; Kong, 2013). In that line, Kong (2013) confirms that presence of family CEO impacts positively on professional skills, work implication, labour satisfaction and performing mediating functions among workers (Paek, 2012; Sampaio et al., 2012). Thus, considering all the above, we expect a positive influence of having a family CEO in the relationship between family ownership and hotel's online reputation.H2 The relationship between family ownership and firm's online reputation is positively moderated by the presence of a family CEO.

We draw on a sample of Spanish hotel firms in which the main data was manually collected in several steps and from different sources. We gathered data from the population of Spanish hotel firms (Spanish Statistical Office, 2013). In order to select a representative sample of this population we utilized a stratified random sampling which guarantees a sampling error lower than 2% (for a 95% confidence interval). This random selection process was carried out based on the identification of active Spanish hotels from SABI (Analysis System of Spanish Balance Sheet) database once they had been stratified by their category (number of stars). Later, the hotels were selected for each and every stratum using the Excel (version 2013) random function. Thus, initially our sample was composed of 231 hotels. Later, we eliminated those firms that did not offer financial and corporate information individualized by establishment and we extracted the outliers to avoid distorting the results. The suppression of elements of the sample supposes a loss of information. We have been very cautious, only eliminating the values placed out of the interval (Q1−3RQ; Q3+3RQ) where Q1 is quartile 1, Q3 is quartile 3 and RQ is the inter-quartile range or the difference between quartiles 1 and 3. This treatment of extreme values offers the advantage of robustness. Thus, the final sample was integrated of 157 Spanish hotels. Regarding potential no-response bias, we assessed it by comparing early and late chosen firms by the random selection process. Variables of firms belonging to the first round of random process (85% of the sample) were contrasted with those belonging to the second round of random process (15% of the sample). As t-Student and chi-squared tests showed that there are not significant differences between the two groups, we concluded that non-response bias is not a concern.

Three distinct sources of information have been used to collect our data, minimizing then the risk of common method variance biases (Podsakoff et al., 2003). First, financial and corporate governance information was obtained from SABI database, gathering for year 2014 the economic and financial situation of our sample of hotels from official registers. Secondly, information regarding online reputation, online reviews and number of rooms of hotels were collected from TripAdvisor website on April 23rd 2014. To obtain homogeneous information, a short-time span was ensured using a special programme, which provided the information in a few minutes, following a similar procedure to Yacouel and Fleischer (2012). Finally, data regarding whether the hotel belongs to a chain or not was captured from hotels websites.

Variables measurementA summary list of our dependent, independent, moderating, and control variables, together with their definitions and sources, is provided in Table 1.

Variables description.

| Variable | Description | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Dependent variables | ||

| Online reputation | Average online popularity ranking calculated in a 0–100 scale as: 100−[(TripAdvisor ranking position/Number of hotels in TripAdvisor ranking)*100] | TripAdvisor Website |

| Explanatory variables | ||

| Family ownership | Fractional equity ownership of the family (subsequently centred) | Own elaboration from SABI database |

| Family CEO | Dummy variable taking value 1 if the CEO of the firm is a family member and value 0 otherwise | Own elaboration from SABI database |

| Control variables | ||

| Chain | Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm belongs to a hotel chain and value 0 otherwise | Hotels Websites |

| Rooms | Number of rooms | TripAdvisor Website |

| Online reviews | Number of online user reviews | TripAdvisor Website |

| Age | Number of years from firm inception | SABI database |

| Generation | Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm is more than 30 years old, and value 0 otherwise | Own elaboration from SABI database |

Online reputation is the dependent variable and it is measured as the online popularity ranking available in TripAdvisor website (Ye et al., 2009). In order to build the TripAdvisor popularity ranking, an algorithm is utilized, which is based on travellers’ reviews, and includes three primary factors that have an impact on the ranking the quality of reviews (considering location, quality of rest, rooms, service, quality-price and cleanliness), the quantity of reviews (considering the number of reviews received) and the age of reviews (considering that older reviews have less impact than recent reviews) (TripAdvisor Popularity Ranking, 2017). This measure has been previously used in literature as a proxy of online reputation in hotel industry (Marchiori and Cantoni, 2011; Yacouel and Fleischer, 2012; Chevalier and Mayzlin, 2003), and it is relevant for online reputation research because the aforementioned website provides information available for many people simultaneously and they can develop views similar to those expressed previously (Marchiori and Cantoni, 2011). According to Chevalier and Mayzlin (2003) and Casaló et al. (2015), this rating provides a standardized measure that is consistent across all hotels in TripAdvisor.

Family ownership is our independent variable that has been measured as the fractional equity ownership of the family, that is to say, as the proportion of common shares held by the family shareholders (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007; Hsu, 2011). To capture this variable, the percentage of firm shares held by shareholders having the same surnames is tabulated for each firm (Hamelin, 2012). Although centering has no consequence on the estimation accuracy, hypothesis tests, or standard errors of regression coefficients, this reduces multicollinearity (Hayes, 2013). For this reason, we centred family ownership, by taking each score and subtracting from each the mean of all scores.

Family CEO is our moderating variable that has been measured as a dummy variable that categorized as 1 when the CEO is a family member and 0 otherwise, following similar operationalization of other studies (Cruz et al., 2010). We identify whether the CEO belong to the family or not based on the matching between the CEO surnames and those of the family shareholders and directors (Villalonga and Amit, 2006).

Control variables. To control some other factors that might affect firm reputation, we take into consideration whether the hotel belongs to a chain or not, as a measure of firm independence (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007), the number of rooms of the hotels, as a measure of firm size (Peters and Kallmuenzer, 2015), the number of online reviews, as a measure of firm relevance (Duan et al., 2008; Sparks and Browning, 2011), firm age, as a representation of family and firm maturity (Singal, 2014) measured as a number of years from the firm inception; and generation, as a proxy to measure generational stage of the family firm (Ward, 1988; Pindado et al., 2015), using age of the firm to distinguish between first generation and second or later generation, considering 30 years as the cut-off point (Fiss and Zajac, 2004).

Research designWe tested our hypotheses by means of multiple regression analyses, which were specified as follows:

where i indexes the firm, t indexed time, and μit denotes the error term.Preliminary, model 1 only measures the effect of control variables on online reputation, as specified by Eq. (1). Model 2 has been generated to test hypothesis 1, to find out if there is a positive direct relationship between the level of family ownership and online reputation. Family CEO is entered as a variable in model 3. Finally, model 4 is utilized to examine whether the relationship between family involvement in ownership and hotel online reputation, is moderated by family management, through the consideration of CEO family status, as we stated in hypothesis 2. We used an interaction model in which the effect of the independent variable X (family ownership) on the dependent variable Y (online reputation) depends on the coefficients (β) of X and the interaction term XZ (Family ownership*Family CEO). Therefore, we calculated the derivative of regression model 4 (∂online Reputation/∂family ownership=β1+β3 Family CEO) to test if family ownership and online reputation are statistically related (at the value of Family CEO), with the substantive significance of the relationship given by the direction and magnitude of the ∂online reputation/∂family ownership estimate (Vanderkerkhof et al., 2015).

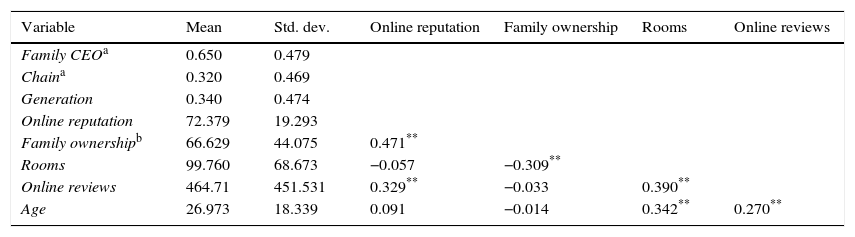

ResultsDescriptive statistics and regression resultsBy and large, the sample under study is characterized by medium-size firms not belonging to a hotel chain and with a long period of experience. The average number of hotel rooms is 99.76 whereas the average of years from inception is 27, similar to the numbers (112 and 20, respectively) in the overall Spanish hotel industry (Spanish Statistical Office, 2013). Thirty two percent of our sample includes hotels belonging to a chain, analogous again to the percentage reported for the whole Spanish hotel industry (29.56%) (Hosteltur, 2013). In terms of family involvement, on average, families hold about 66% of hotel ownership whereas almost 60% of hotels are headed by a family CEO. Regarding online reputation, the online customer valuation of hotels is positive and quite high (72.38 in a 0–100 scale) taking into account a considerable number of online reviews per hotel (464). Therefore, the comparison of some selected characteristics of the sample with the population of the Spanish hotel industry suggests that despite some differences (e.g. five and four-star hotels are overrepresented among hotels of the sample compare to population), the selected characteristics of our sample (average number of rooms, average of years from inception and percentage of hotels belonging to chain) are similar to the Spanish hotel industry. A comparison of selected features of sample firms to population of Spanish hotel industry and descriptive statistics for all variables and correlation matrix are described in Tables 2 and 3, respectively.

Comparison of selected characteristics of sample firms to population of Spanish hotel industry.

| Panel A. Comparing average number of rooms, average of years from inception and % of hotels belonging to chain | ||

|---|---|---|

| Population | Sample | |

| Hotel rooms | 112 | 99.76 |

| Age | 20 | 27 |

| Chain | 29.56% | 32% |

| Panel B. Comparing the number and proportion of hotels included in each category (number of gold stars) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold stars | Population (number of hotels) | Population (%) | Sample (number of hotels) | Population |

| Five | 216 | 3% | 10 | 6% |

| Four | 1657 | 27% | 59 | 34% |

| Three | 1854 | 30% | 52 | 30% |

| Two | 1536 | 25% | 35 | 20% |

| One | 934 | 15% | 18 | 10% |

| Total | 6197 | 100% | 174 | 100% |

Descriptive statistics and correlations.

| Variable | Mean | Std. dev. | Online reputation | Family ownership | Rooms | Online reviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family CEOa | 0.650 | 0.479 | ||||

| Chaina | 0.320 | 0.469 | ||||

| Generation | 0.340 | 0.474 | ||||

| Online reputation | 72.379 | 19.293 | ||||

| Family ownershipb | 66.629 | 44.075 | 0.471** | |||

| Rooms | 99.760 | 68.673 | −0.057 | −0.309** | ||

| Online reviews | 464.71 | 451.531 | 0.329** | −0.033 | 0.390** | |

| Age | 26.973 | 18.339 | 0.091 | −0.014 | 0.342** | 0.270** |

Online reputation: the online customer valuation regarding location, quality of rest, rooms, service, quality-price and cleanliness (in a 0–100 scale). Family ownership: the proportion of common shares held by the family shareholders. CEO family status: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the CEO of the firm is a family member and value 0 otherwise. Chain: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm belongs to a hotel chain and value 0 otherwise. Rooms: the number of rooms. Online reviews: the number of online user reviews. Age: the number of years from firm inception. Generation: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm is more than 30 years old, and value 0 otherwise.

Table 4 shows multiple regression results. We examined multicollinearity through variance inflation factors (VIF), finding moderate levels of correlation between our variables as all VIF values were below the suggested warning level proposed in previous studies (Hair et al., 1998). According to the results, hypothesis 1, which was based on the argument that online reputation is more favourable when the ownership in the hands of the family is higher, is supported because the estimated parameter in model 2 indicates that there is a significant positive relationship between online reputation and family ownership (β=0.402; p<0.01). Family CEO showed a positive and significant effect on online reputation, as did family ownership, in model 3. In model 4, we test our hypothesis 2: the positive moderating effect of family management on the relationship between family ownership and online reputation. The cross-product term (Family ownership*Family CEO) is statistically significant above and beyond the statistical significance of its constituent parts (family ownership and family CEO) and R2 increases when product term is introduced, confirming its positive influence on online reputation.

OLS regressions. Effects of family ownership on firm online reputation and moderating influence of family CEO.

| Panel A. Multiple regression analyses (OLS) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

| β | VIF | β | VIF | β | VIF | β | VIF | |

| Chain | −0.067 (0.407) | 1.148 | 0.053 (0.491) | 1.262 | 0.045 (0.565) | 1.268 | 0.043 (0.574) | 1.268 |

| Room | −0.371*** (0.000) | 1.365 | −0.232*** (0.007) | 1.518 | −0.208** (0.017) | 1.563 | −0.187** (0.031) | 1.590 |

| Online reviews | 0.355*** (0.000) | 1.345 | 0.277*** (0.001) | 1.393 | 0.287*** (0.001) | 1.400 | 0.289*** (0.000) | 1.400 |

| Age | 0.120 (0.418) | 3.950 | 0.058 (0.675) | 3.981 | 0.054 (0.693) | 3.982 | 0.048 (0.725) | 3.985 |

| Generation | −0.019 (0.898) | 3.952 | 0.033 (0.810) | 3.973 | 0.047 (0.732) | 3.987 | 0.056 (0.681) | 3.992 |

| Family ownership | – | 0.402*** (0.000) | 1.281 | 0.243** (0.048) | 3.166 | 0.120 (0.385) | 4.098 | |

| Family CEO | – | – | 0.204* (0.093) | 3.111 | 0.146 (0.242) | 3.323 | ||

| Family ownership×family CEO | – | – | – | 0.223* (0.063) | 3.067 | |||

| N | 157 | 157 | 157 | 157 | ||||

| Adjusted R2 | 0.132 | 0.258 | 0.267 | 0.279 | ||||

| R2 change | 0.160 | 0.126 | 0.009 | 0.012 | ||||

| F change | 5.752*** | 10.023*** | 9.106*** | 8.542*** | ||||

| Durbin–Watson | 1.816 | |||||||

| Wald test: total effects (β1+β3) | 0.343*** | |||||||

| Panel B. Conditional effect of X (family ownership) on Y (online reputation) at values of the moderator (family CEO) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family CEO | β | Std. dev. | t | p | LLCI | ULCI | |

| 0 | 0.053 | 0.061 | 0.870 | 0.385 | −0.067 | 0.175 | |

| 1 | 0.282 | 0.107 | 2.628 | 0.010 | 0.070 | 0.495 | |

Online reputation: the online customer valuation regarding location, quality of rest, rooms, service, quality-price and cleanliness (in a 0–100 scale). Family ownership: the proportion of common shares held by the family shareholders. CEO family status: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the CEO of the firm is a family member and value 0 otherwise. Chain: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm belongs to a hotel chain and value 0 otherwise. Rooms: the number of rooms. Online reviews: the number of online user reviews. Age: the number of years from firm inception. Generation: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm is more than 30 years old, and value 0 otherwise.

VIF: Variance inflation factor. LLCI/ULCI: lower/upper-limit of confidence interval (95%). p values in parentheses.

To rightly interpret this moderating effect, the calculation of marginal effects is essential, considering not only the coefficient of the interaction term but also the coefficient of family ownership and the value of our moderator family CEO. We use the PROCESS tool (Hayes, 2013), a custom dialogue box for SPSS, which automatically produces output from the pick-a-point approach to probing interactions whenever a moderation model is specified with family ownership's effect on online reputation moderated by family CEO. As family CEO is dichotomous, PROCESS generates θFamily Ownership→Online Reputation for the two groups defined by values of family CEO, along with standard errors, and p-values for a two-tailed test of the null hypothesis that θFamily Ownership→Online Reputation=0. We can examine the simple slopes and interpret the results as follows (Table 4, panel B): (1) when there is a non-family CEO, there is a non-significant relationship between family ownership and online reputation (β=0.053; t=0.870; p=0.385); (2) when there is a family CEO, there is a significant relationship between family ownership and online reputation (β=0.282; t=2.628; p=0.010). Additionally, the sum of the coefficients of Family ownership and Family ownership*Family CEO, which reflects the total effect of the variable on online reputation when a family CEO is present (β1+β3), is positive and significant, as the Wald test indicates (β=0.343; p<0.01). Therefore, hypothesis 2 is supported, that is to say, family CEO has a moderating influence on online reputation reactions to family ownership. Fig. 1 graphically represents the marginal effect of family ownership on online reputation by family CEO status.

Finally, some control variables such as online reviews and firm size also have significant effects on online reputation. In particular, the number of online reviews positively affects online reputation, while hotel size has a strong negative effect on it. Therefore, it seems that, regardless of the family presence in ownership and management, smaller hotels have better online reputation than larger ones and that online reputation is more likely to emerge in hotels with a higher number of online reviews.

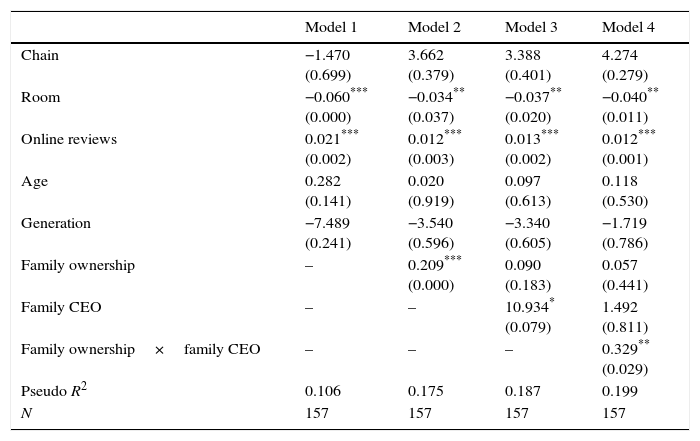

Robustness analysisAfter testing hypothesis with multiple regressions approach, we found our results also robust to other alternative methodologies. Firstly, we have substituted the OLS method estimation for the quantile regression (Table 5). Whereas the OLS estimation approximates the conditional mean of the variables given certain values of the predictor variables, quantile regression aims to estimate the conditional median. One advantage of quantile regressions over OLS regressions is that the former are more robust against outliers, avoiding assumptions about the parametric distribution of the error process. As shown in Table 5, the results are very similar to OLS when quantile regressions are used, confirming the validity and robustness of our outcomes.

Quantile regressions. Effects of family ownership on firm online reputation and moderating influence of family CEO.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chain | −1.470 (0.699) | 3.662 (0.379) | 3.388 (0.401) | 4.274 (0.279) |

| Room | −0.060*** (0.000) | −0.034** (0.037) | −0.037** (0.020) | −0.040** (0.011) |

| Online reviews | 0.021*** (0.002) | 0.012*** (0.003) | 0.013*** (0.002) | 0.012*** (0.001) |

| Age | 0.282 (0.141) | 0.020 (0.919) | 0.097 (0.613) | 0.118 (0.530) |

| Generation | −7.489 (0.241) | −3.540 (0.596) | −3.340 (0.605) | −1.719 (0.786) |

| Family ownership | – | 0.209*** (0.000) | 0.090 (0.183) | 0.057 (0.441) |

| Family CEO | – | – | 10.934* (0.079) | 1.492 (0.811) |

| Family ownership×family CEO | – | – | – | 0.329** (0.029) |

| Pseudo R2 | 0.106 | 0.175 | 0.187 | 0.199 |

| N | 157 | 157 | 157 | 157 |

Online reputation: the online customer valuation regarding location, quality of rest, rooms, service, quality-price and cleanliness (in a 0–100 scale). Family ownership: the proportion of common shares held by the family shareholders. CEO family status: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the CEO of the firm is a family member and value 0 otherwise. Chain: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm belongs to a hotel chain and value 0 otherwise. Rooms: the number of rooms. Online reviews: the number of online user reviews. Age: the number of years from firm inception. Generation: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm is more than 30 years old, and value 0 otherwise.

p values in parentheses.

Secondly, we also utilized Generalized Regression Neural Network (GRNN) analysis, which is designed to continuous dependent variables. Prior research has confirmed that GRNN is useful to analyze firm data because it is impassive to atypical values (Pao, 2008). Likewise, GRNN analysis can measure the impact of variables in the regression models providing the sensitivity of network results to the change of independent variables. Thus, each and every independent variable has an impact value on the dependent variable, which is expressed in percentage units and they must come to 100%. Furthermore, looking for a higher robustness of the results applying GRNN, we have split the sample, devoting 80% of the firms to build the models (training data) and 20% of the companies to test the models previously generated (testing data). The obtained results are displayed in Table 6. As we can test with model 2, family ownership variable is the most important, having the 31.48% of the impact on online reputation. Therefore, H1 is confirmed again. GRNN analysis also confirms H2, as the multiplicative interaction is the most relevant variable in model 4, representing the 30.89% of the influence on online reputation.

Generalized regression neural network analyses. Effects of family ownership on firm online reputation and moderating influence of family CEO.

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | Training | Testing | |

| Impact % | Impact % | Impact % | Impact % | |||||

| Chain | 2.532 | – | 1.304 | – | 1.639 | – | 1.021 | – |

| Room | 36.573 | – | 18.630 | – | 13.088 | – | 11.302 | – |

| Online reviews | 38.906 | – | 30.165 | – | 26.133 | – | 26.336 | – |

| Age | 19.956 | – | 17.799 | – | 1.279 | – | 0.612 | – |

| Generation | 2.033 | 0.613 | 0.741 | 0.528 | ||||

| Family ownership | – | – | 31.489 | – | 30.152 | – | 14.997 | – |

| Family CEO | – | – | – | 26.968 | – | 14.310 | – | |

| Family ownership×family CEO | – | – | – | – | – | 30.894 | – | |

| N | 157 | – | 157 | – | 157 | – | 157 | – |

| R2 | 0.372 | – | 0.473 | – | 0.540 | – | 0.615 | – |

| F | 108.411*** | – | 17.942*** | – | 15.770*** | – | 9.246*** | – |

| RMSE | 98.365 | 98.621 | 95.104 | 95.630 | 93.649 | 94.081 | 91.502 | 91.860 |

| MAE | 9.429 | 9.768 | 8.844 | 8.911 | 8.803 | 8.866 | 9.100 | 9.181 |

Online reputation: the online customer valuation regarding location, quality of rest, rooms, service, quality-price and cleanliness (in a 0–100 scale). Family ownership: the proportion of common shares held by the family shareholders. CEO family status: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the CEO of the firm is a family member and value 0 otherwise. Chain: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm belongs to a hotel chain and value 0 otherwise. Rooms: the number of rooms. Online reviews: the number of online user reviews. Age: the number of years from firm inception. Generation: Dummy variable taking value 1 if the firm is more than 30 years old, and value 0 otherwise.

RMSE: Root Mean Square Error. MAE: Mean Absolute Error.

The influence of family involvement on hotels online reputation remains unexplored to date despite both the significant presence of families in business structures (Merino et al., 2015) and the increasing impact of electronic word-of-mouth customers activities on the online reputation of hospitality firms (Cantallops and Salvi, 2014). Since governance determines firm's abilities and intentions (Mishina et al., 2012), it can be expected that family involvement in the hotels’ ownership and management has a strong influence on resources orientations and behavioural purposes that affect firm online reputation (Chrisman et al., 2012). Following this reasoning, this paper contributes to filling this gap by analysing the impact of family involvement on a sample of 157 Spanish family hotels. Building on insights from familiness view (Habbershon and Williams, 1999), organizational identity theory (Zellweger et al., 2013) and SEW framework (Gomez-Mejia et al., 2007), we proposed that higher family ownership positively influences hotels online reputation and that the presence of a family CEO strengthens this relationship.

Our results, as expected, our results show that hotels controlled by a family, in terms of majority ownership, have a favourable effect on a firm's online reputation. Family controlled hotels involve, then, greater trustworthy image, long-term relationships, closer identification with the firm, and socioemotional aims that influence favourably their reputation (Cruz et al., 2010; Zellweger et al., 2013). Additionally, it seems to be in accordance with the studies which claim that family involvement triggers greater concerns regarding social responsibility (Singal, 2014), more enthusiasm and identification with the enterprise and higher intimacy and interconnection with customers (Getz and Carlsen, 2005) and more emotional attachment to the business (Morrison, 2002). These potential advantages of family firms in the hotel industry can also contribute to a better reputation as a means to obtain superior performance.

Furthermore, family hotels managed by a family CEO exhibit an increasing online reputation, which can be coherent with the arguments of closer identification and commitment (Miller and Le Breton-Miller, 2006) and greater SEW preservation (Cruz et al., 2010; Gomez-Mejia et al., 2011). In terms of the hotel industry literature, the positive impact of a family CEO on internal professional skills, work implication and labour satisfaction (Kong, 2013) also have as a consequence an external favourable hotel online reputation (Steier, 2001). Taken this into consideration, our results do not find support for the negative implications – both, on employee relationships and on long-term planning (Paek, 2012; Sampaio et al., 2012) – of having a family CEO in terms of online reputation.

In addition, our findings indicate that family involvement in a hotel generates greater online reputation, but in different ways. While family ownership dimension exerts a direct and significant effect on online reputation, the management dimension, considered by the CEO family status, plays a positive moderating role, intensifying the relationship between family ownership and online reputation. This result is consistent with the assertions of Miller and Le Breton-Miller (2006) referring to family CEOs as people who have a great level of power and discretion to act without owners, board or top team intervention. It seems that family ownership interact positively with the family CEO in order to create a virtuous circle of long-term commitment, socioemotional wealth preservation and future generations’ endurance, which make family highly involved and compromised with online reputation (Deephouse and Jaskiewicz, 2013).

This study, therefore, academically contributes in several ways to the literature of hospitality and family business. Firstly, this paper contributes an unexplored area to data, giving theoretical and empirical support to the positive influence of family involvement on hotel online reputation. In that vein, our results point out as a positive outcome in terms of reputation the presence of families owning and managing hotels (Getz and Carlsen, 2005). Secondly, we contribute to the understanding of the heterogeneity of family firms (Chua et al., 2012), by means of an interactive analysis of the influence of family ownership and management dimensions on online reputation, acknowledging the direct effect of the former and the indirect effect of the latter. Thirdly, this paper shows evidence regarding the importance and positive impact of family involvement for hospitality industry development in Spain, a context usually characterized by a high embeddedness of families into the business (Merino et al., 2015). And fourthly, this research proposes and establishes the electronic assessment provided by customers as a proper measure of hotels online reputation, a proxy that is increasingly accepted in order to consider as an important part of the picture for analysing hotels competitiveness (Melián-González et al., 2013).

Regarding practical implications, one of the most notable practical suggestions of our study is for investors interested in firms with competitive advantages associated to reputation. They should consider in their investment decisions what is the degree of involvement of owning families in the ownership and management of hotels as they influence reputations levels of hotels and, in turn, should be a good indicator of firms’ sustainability. Another important implication is related to the management of online reputation of hotels, which should be a relevant criteria for the decision of selecting a family CEO in for managing the firm, as it may be essential for improve reputation. Family CEO is especially important in the hotel sector where his/her functions tend to be even closer to the customers (and rest of stakeholders). Finally, our results also should be considered in case of hotels with a low degree of familiness in terms of ownership, on which an appropriate combination of family and non-family managers – including the CEO – should be more consistent in terms of online reputation.

Finally, this study is not without limitations, which, in turn, may provide fruitful lines for future research. Firstly, the influence of socioemotional wealth preservation, although mentioned in the arguments of the papers, should be estimated in a more direct way in the relationships between a hotel's online reputation and family involvement (Berrone et al., 2012). Secondly, a direct interaction between online reputation and firm performance would be desirable in order to interrelate it with CEO family status. General literature has confirmed that improving CEO reputation, although not normally associated to higher future firm performance, is usually related to greater satisfaction of stakeholders – mainly customers and shareholders – and in turn, to subsequent improvements in the reputations of the top managers themselves (Sánchez-Marín and Baixauli-Soler, 2014). Nevertheless, the increase in power and discretion of the highly reputed CEO can also explain arrogant or excessively risky behaviour, a lack of ethical principles, or the neglect of management tasks that, in the long term, provoke a decrease on online reputation and subsequently, firm performance (Wade et al., 2008). Fourthly, a complete examination of these relationships should incorporate the positive and negative aspects of the usually powerful family CEOs in family hotel firms in order to see how they fit into the pursuit of favourable reputation, as well as the achievement of business goals (firm performance) and/or socioemotional family endowments. And fifthly, the use of cross-sectional data may limit the causality of the proposed and analyzed relationships. Future studies should address this important issue. To date, unfortunately we do not have the information available to run a longitudinal analysis but, meanwhile, we have tried to show literature regarding several measures of robustness (Michiels et al., 2013), which, at some extent, guarantee the steadiness of hypothesized relationships.

Nevertheless, and summing up, this paper constitutes an important first step in highlighting the importance of family involvement, both in terms of ownership and management, as an essential governance mechanism for developing a favourable online reputation for hotels.