The literature regarding entry timing suggests that pioneering orientation (PO) is a key determinant factor of new product performance (NPP) due to ‘first mover advantages’. The contradictory results and specific biases raise a research gap on which conditions and processes lead PO to a higher NPP. This paper proposes to fill this gap by designing and testing a model examining to what extent development of competitive tactics drive and explain the way from PO to NPP. We test the model on a sample of 224 footwear firms. Results show that, separately, each of the competitive tactics has a total mediating effect linking PO with NPP. Introducing the competitive tactics into a multiple mediator model the routes from PO to NPP through low cost and innovation differentiation are relevant and compatible. However, marketing differentiation is less effective. The study provides new ways of linking the entry timing and advantage strategy perspectives.

Strategies based on time, such as pioneering orientation (PO), are the key for obtaining competitive advantages in today's environment, and is for this reason that “one of the strategic launch decisions examined most frequently is when to enter the market” (Moreno-Moya and Munuera-Aleman, 2015: 9). The PO is defined as a strategy posture whereby the organisations consistently adopt cross-product market pioneering behaviours across (Mueller et al., 2012; Zahra, 1996). Market pioneer is the first firm to offer a distinctively new product to the market (Covin et al., 2000). The traditional approach of the entry timing highlights the significant competitive advantages of a PO (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998, 2013). However, several authors establish that PO also has important disadvantages, which can counter the obtaining and maintaining of first-mover advantages (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998; Markides and Sosa, 2013).

The current literature on this topic identifies a research gap about the need for further research on the prevalence of advantages or disadvantages, including not only direct relationships but, mediating or moderating relationships, including new measures of performance as well as to analyse these relationships through structural equation modelling (Moreno-Moya and Munuera-Aleman, 2015). Furthermore, traditional entry timing literature explains that potential first-mover advantages become performance through different drivers (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988). Entry timing literature has tried to identify these drivers from different perspectives – strategic, economic, consumer behaviour, etc. – (Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007; Gómez et al., 2016). However, it is necessary to develop new studies which clearly identify and contrast empirically these drivers to understand how PO leads to first-mover advantages, since the previous assumption considering some potential advantages are inherent to PO can not stand anymore (De Castro and Chrisman, 1995; Gómez and Maicas, 2011). In order to fill this research gap and following the proposals of Markides and Sosa (2013), the present study designs and tests a model that allows analysis of the role of competitive tactics – orientated to low cost, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation – as drivers of the relationship among PO and new product performance (NPP). We consider that key advantages of PO are related to differentiation and low cost benefits (Kerin et al., 1992), and although past research has considered that these effects are inherent to PO, following De Castro and Chrisman (1995), the competitive tactics play a key role to materialise the aforementioned advantages. We suggest a mediating effect of competitive tactics to lead PO to NPP. Specifically, we propose that firms follow low-cost and differentiation competitive tactics, deploying appropriate isolating mechanisms, to realise potential low-cost and differentiation sustainable advantages derived from the PO (Wu et al., 2007). Therefore, a more enriched view about the sources of sustaining the competitive advantage can be obtained by drawing insights from entry timing and competitive advantage approaches (Ruiz-Ortega and García-Villaverde, 2008; Zhao et al., 2014).

The main aim of this study is to determine the extent to which the development of competitive tactics oriented to low-cost competitive, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation can drive and explain how firms that develop a PO achieve a superior NPP. In addition, we explore if the three ways from the PO to the success of new products through competitive tactics are compatible in a multiple mediator model.

The main contribution of this paper is to identify the necessary mediating role of competitive tactics to ensure that the potential competitive advantages on low cost and differentiation derived of PO materialise on NPP. Thus, we provide new theoretical linkages, still limited, between entry timing perspective (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988, 1998) and competitive advantage perspective (Porter, 1985) to explain NPP, as it is suggested by De Castro and Chrisman (1995). Furthermore, in this study we avoid some biases found in previous studies regarding first mover advantages. First, avoiding the simplification of a great majority of studies that only differentiate between pioneer and follower firms, we consider the PO concept is based on market pioneer (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998). In this sense, an organisation that consistently exhibits market pioneering behaviours across product lines could be said to have adopted a PO (Mueller et al., 2012).1 Second, as opposed to the utilisation of self-definition measures, we measure PO as a continuum (Covin et al., 2000; Zahra, 1996), in which the starting point is the pioneer company, being the first firm that introduces a new product into the market, and the final point is the late follower, being the company entering late into a developed industry. Third, in relation to the bias on the performance measurement and the tendency of many studies to include the market share, we use NPP and consider it broadly in terms of profitability2 and sales growth of new products (Morgan et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2009). Fourth, in contrast to those studies examining only the direct effect of the PO in the firms’ performance (Robinson and Fornell, 1985; Urban et al., 1986), we include the influence of mediating variables. Finally, we develop the study in a sample of firms of a mature industry, the footwear industry in Spain, questioning the relevance of the traditional direct advantages linked to PO in these sectors (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988, 1998).

Our paper is divided into six sections. In the first, we develop an introduction to the study and we expose the proposed aims. In the two subsequent sections, we develop the theoretical framework and expose the proposed hypotheses. Sections four and five gather methods for developing our empirical study and the results obtained. Finally, in the sixth section, we provide the discussion and conclusions obtained in the study, limitations, managerial implications and future lines of research.

Theoretical frameworkEntry timing perspective: pioneering orientationTraditionally, the literature regarding entry timing has highlighted the superior levels of performance obtained by pioneer firms (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988). Following Covin et al. (2000: 177), we consider market pioneering “a particular form or manifestation of entrepreneurial behaviour whereby the organisation proactively creates or is among the first to enter a new product-market arena that others have not recognised or actively sought to exploit”. In contrast to the studies that focus on the roles of pioneer or follower, we consider the PO as a continuum of pioneering behaviours such that a high level of PO indicates a firm operating with a heavy bias towards early entry of uniquely innovative products into the market, while a low orientation indicates less of a reliance upon early entry as a business strategy as well as the introduction of more incrementally new products (Mueller et al., 2012). In our view, PO comprises a sum of entry timing decisions that depend on how managers perceive potential first mover advantages and disadvantages (Song et al., 2013).

Traditional entry timing perspective highlights that pioneer firms can take several low-cost and differentiation advantages that allow them to obtain a greater performance (Kang and Montoya, 2014). Thus, they have a better market position that makes the appropriation of scarce resources easier for them in relation to followers, their temporal position of monopoly allow them to differentiate from competitors and to access a broad customer base, they have an early access to the best distribution channels and promote the development of suitable investments to obtain differentiation advantages, they also have an influence on consumer preferences, and allow them to build entry barriers arising from cost advantages obtained (Kerin et al., 1992; Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998; Robinson and Chiang, 2002).

Studies have also pointed out several disadvantages for pioneer firms, which can negatively affect their performance, as changes in customers’ needs, the inertia arising from competitive success, pioneering inflexibility and the “vintage” and “free rider” effects of the follower firms (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988; Markides and Sosa, 2013). The doubts about the existence of net pioneer advantages are accentuated when firms face dynamic environments in technology and demand (Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007), in which new product success is not so evident.

In the last two decades, several surveys have exposed methodological limitations in the empirical studies of entry timing that raise doubts about the results obtained (Gómez and Maicas, 2011; Kerin et al., 1992; Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998, 2013; Szymanski et al., 1995; among others). Methodological limitations and the recognition of pioneer disadvantages question the net advantage in general performance for pioneer firms, and particularly, the NPP advantage.

Lieberman and Montgomery (1988) highlight the role of isolating mechanisms to explain the effectiveness of the first mover advantages. Suarez and Lanzolla (2007) show that pioneer firms could preempt competitors from accessing valuable spaces or production resources, achieve economies of scale from initial investments, create cost advantages via learning economies and practices, benefit from patenting key innovation, generate switching cost arising from buyers’ habit formation, consumer learning and reputation advantages, and benefit from high buyers’ searching cost, among other isolating mechanisms. Recently, literature highlights different classifications of first mover advantages isolating mechanisms (Gómez et al., 2016): resource pre-emptions, proprietary experience effects and leadership reputation (Day and Freeman, 1990), economic, pre-emption, technological and behavioural factors (Kerin et al., 1992); producer- and consumer-based (Golder and Tellis, 1993); technology leadership, preemption of scarce assets and switching costs/buyer choice under uncertainty (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988). Despite this extensive literature there are few studies that have tested the effectiveness of specific isolating mechanisms (e.g. Bouldin and Christen, 2008; Gómez and Maicas, 2011).

We consider that competitive tactics are linked to isolating mechanisms, since depending on the competitive tactic the firm follows, different isolating mechanisms are deployed (Gómez and Maicas, 2011; Markides and Sosa, 2013; Mueller et al., 2012). We propose that competitive tactics can drive the way from the PO to the NPP.

Scant contributions propose that the PO effect on a firm's performance can differ according to competitive tactics (De Castro and Chrisman, 1995; Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001). Other studies highlight divergent interrelations and constraints among entry timing and different competitive tactics to explain firm performance (Covin et al., 2000; Ruiz-Ortega and García-Villaverde, 2008). However, to our knowledge and in spite of the interesting implications, no research has attempted to analyse the mediating role of competitive tactics in the relationship between PO and NPP.

Competitive advantage perspective: competitive tacticsCompetitive advantage perspective, proposed by Porter (1985), recognises the importance of an attractive position (competitive advantage) derived from the strategic orientation of the firm together with industry structure. Following the traditional focus of Porter (1985), competitive strategy sets the orientation of the firm to get a favourable competitive position in the industry. Competitive tactics are the actions developed by a firm to establish its strategy (Barney, 2002: 13); these tactics therefore reflect its strategic orientation and form the basis of competition (Covin et al., 2000).

Porter's typology (Porter, 1985) differentiates among two main competitive advantages – low cost and differentiation–. Following Miller (1986), differentiation advantages can be achieved through two types of competitive tactics – innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation–. We propose the adaptation developed by Spanos and Lioukas (2001), which draws a distinction between the competitive tactics oriented to low costs, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation, considered as continuous factors.3

Low-cost competitive tactics are the clearest, as the actions through which the firm tries to become a low-cost producer in its industry. In order to achieve this aim, the firm develops economies of scale or scope, through access to resources or new technologies, increasing operational efficiency, improving quality control, etc. (Porter, 1985). On the other hand, differentiation tactics involve a different orientation from which the firm will seek to obtain high levels of performance from products that consumers perceive as unique and different (Porter, 1985). These differentiation tactics may be based on innovation – product or process–, or on the marketing effort. Thus, differentiation through innovation tactics will allow firms to enhance their appeal and reputation with customers for novelty in their products, processes and activities (Spanos and Lioukas, 2001). Firms can also develop differentiation tactics on the basis of the implementation of marketing activities designed to help the firm to influence consumer preferences and create in their mind the idea of product exclusivity (Gotteland and Haon, 2010).

The link between the entry timing and competitive advantage perspectivesEntry timing and competitive advantage perspectives have been largely developed separately. However, we find several studies that connect these two approaches (Kerin et al., 1992; De Castro and Chrisman, 1995; Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998; Covin et al., 2000; Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001; Ruiz-Ortega and García-Villaverde, 2008; Zhao et al., 2014; among others). Both perspectives aim to achieve sustainable competitive advantages. Although traditional entry timing perspective suggests that low-cost and differentiation competitive advantages are inherent to PO, the empirical evidence shows that this is not so and specific competitive tactics are needed to achieve sustainable competitive advantages (Kerin et al., 1992; Gómez and Maicas, 2011; Markides and Sosa, 2013). Thus, firms need to develop competitive tactics to get the effectiveness of potential first-mover advantages (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988). Competitive advantage perspective highlights the role of low-cost and differentiation competitive tactics to gain a sustainable competitive position in the industry (Porter, 1985). We propose that low-cost and differentiation tactics are specific actions that reflect the strategic orientation of the firm and they deploy the appropriate isolating mechanisms to realise potential low-cost and differentiation sustainable advantages derived from the PO. Thus, the competitive advantage perspective offers competitive tactics as solid drivers to lead PO to NPP. We propose that drawing insights from both approaches can provide a more enriched view about the sources of sustaining the competitive advantage in low-cost and differentiation.

From this approach, we can link competitive tactics with isolating mechanisms (Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007). Thus, the development of competitive tactics encourages the deployment of specific isolating mechanisms (Kerin et al., 1992; Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007), linked to the classical propose of Lieberman and Montgomery (1988). As we can see in Table 1, low cost competitive tactics display economies of scale from initial investments, cost advantages via learning economies and practices, cost advantages derived from causal ambiguity and imperfectly imitable knowledge and practices and preemption of valuable production resources. Innovation differentiation tactics unfold product and process innovation and patenting key innovations, linked to technology leadership. Finally, marketing differentiation tactics deploy cognitive switching costs arising from buyers’ habit formation, consumer learning and reputation advantages, high buyers’ searching cost and preemption of valuable market segments. Thus, the competitive tactics typology, linked to isolating mechanism, is adjusted to the traditional classification of competitive advantages – low-cost and differentiation – adopted by the entry timing perspective (Kerin et al., 1992).

Links between competitive tactics and deployed isolating mechanisms.

| Competitive tactics (Miller, 1986) | Isolating mechanisms (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1988) | Specific isolating mechanisms (Kerin et al., 1992; Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007; Gómez et al., 2016) |

|---|---|---|

| Low cost | Preemption of scarce assets Technology leadership | Economies of scale from initial investments Cost advantages via learning economies and practices Cost advantages derived from causal ambiguity and imperfectly imitable knowledge and practices Preemption of valuable production resources |

| Innovation differentiation | Technology leadership | Product and process innovation Patenting key innovations |

| Marketing differentiation | Switching cost/buyer choice under uncertainly Preemption of scarce assets | Cognitive switching costs arising from buyers’ habit formation Consumer learning and reputation advantages High buyers’ searching cost Preemption of valuable market segments |

By means of linking entry timing and competitive advantage perspective we propose the development of a causal model that allows us to connect specific factors from both perspectives to explain the firm's NPP. Thus, the link of competitive tactics with the deployed isolating mechanisms can explain and specify the ways by which PO achieves NPP.

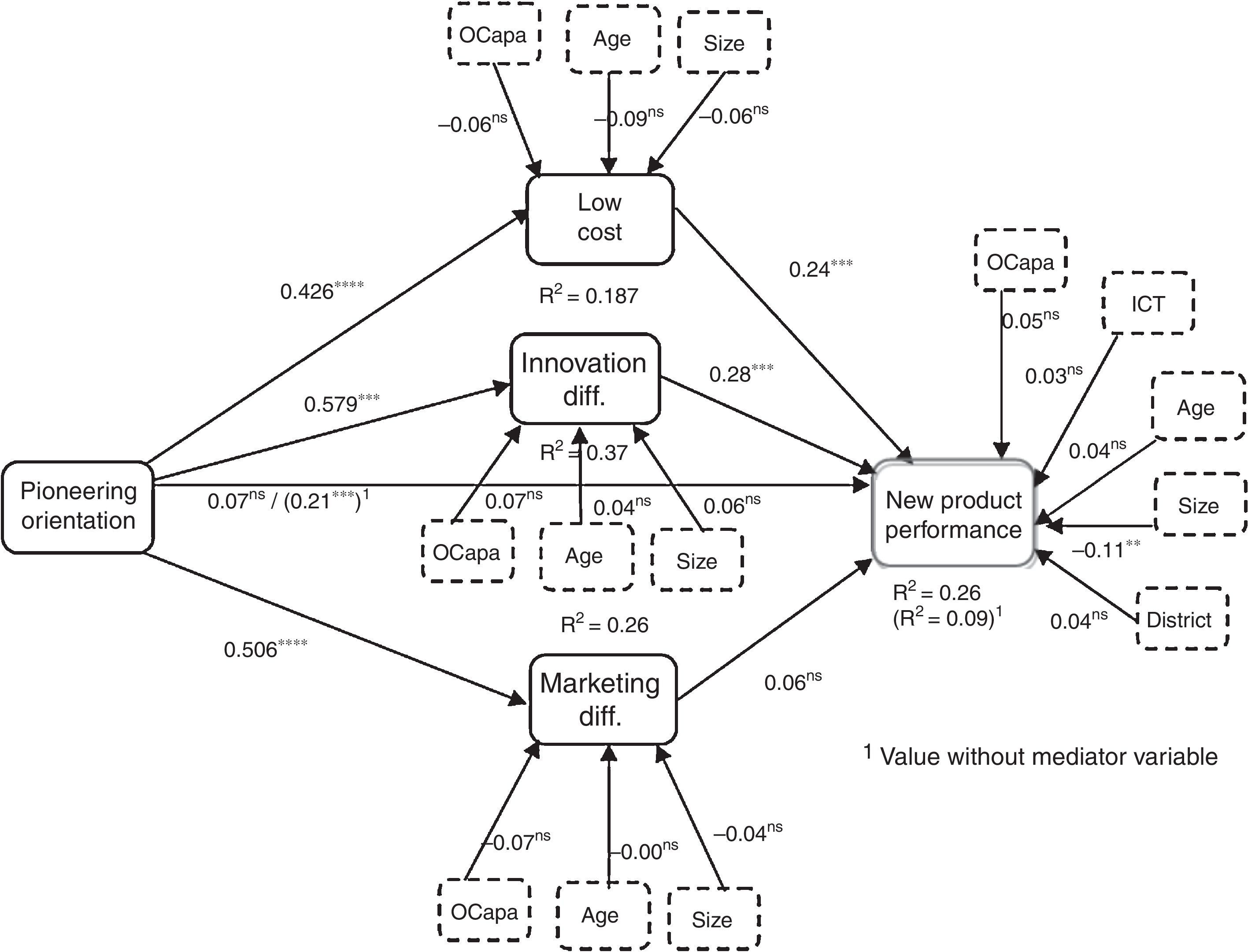

HypothesesPioneering orientation and new product performance: the mediating role of competitive tacticsWe propose that competitive tactics mediate the relationship between PO and NPP (Covin et al., 2000) (Fig. 1). Following Baron and Kenny (1986: 1176) “a given variable may be said to function as a mediator to the extent that it accounts for the relation between the predictor and the criteria. In other words, a mediator variable specifies how or why a particular effect occurs”. Thus, PO creates a high potential for firms to gain competitive advantages in cost and differentiation for new products. However, PO is not a sufficient condition to ensure a high performance of new products. In fact, the reaction of competitors and customers can reduce performance advantages of new products significantly. We consider that those firms capable of driving their PO to develop tactics of low-cost, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation will strengthen their competitive position derived from their temporary monopoly position and achieve greater performance with their new products (De Castro and Chrisman, 1995).

With the aim to raise the hypotheses on the mediator effect of competitive tactics, first we are going to justify the influence of PO on the competitive tactics, then the influence of the competitive tactics on the NPP and, finally, the mechanisms of mediation that lead this relationship.

The influence of pioneering orientation on the competitive tacticsIn the context of the discussion on both the advantages and disadvantages of pioneering and the methodological limitations of the studies, several authors state that the link between PO and competitive tactics is an important basis for obtaining greater performance (Covin et al., 2000; De Castro and Chrisman, 1995; Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001; Zhao et al., 2014). In this sense, pioneer firms will have incentives to develop competitive tactics that enable them to create entry barriers to protect them from imitation and the free-rider effect of late entrants (De Castro and Chrisman, 1995; Miller et al., 1989). Furthermore, we emphasise that the task of a pioneer firm when it comes to the market is to establish a strong competitive position and develop economic, technological and behavioural advantages. Because the critical success factor in an industry tend to be related to product functions and attributes, it is logical to think that pioneer firms will have incentives to develop competitive tactics aimed at both cost and differentiation, taking advantage of the benefits arising from entering the market as pioneer firms (Covin et al., 2000; Miller et al., 1989; Zhao et al., 2014).

The influence of the competitive tactics on NPPFrom the competitive advantage perspective (Porter, 1985) we consider that it is very important for companies to achieve an attractive competitive position derived from their competitive tactics. Through the development of these competitive tactics, firms should help increase customer utility. This utility derives from the fit between the company's offer and the needs of market players. Another effect of the competitive tactics, acting independently or in combination, is that it provides the conditions for sustainable competitive advantage. In this line, there are many studies that analyse and detect a significant influence of competitive tactics on firm performance (Parnell, 2011; among others).

The competitive tactics proposed by Spanos and Lioukas (2001) – low costs, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation – are traditionally linked to NPP. Thus, the firm, through product differentiation, can sell new products at a price significantly above the unit cost of production to achieve higher margins or produce at a lower cost compared to its competitors, thereby increasing significantly its sales.

Mediating effect of low cost competitive tacticsAs highlighted previously, PO is not enough to ensure a high NPP. Thus, the company needs to develop competitive tactics through which to get such a result. Several studies show that pioneer firms tend to achieve lower prices on their products, while gaining direct cost advantages over competitors (Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001; Miller et al., 1989). However, follower companies will try to imitate the successful products of pioneer firms, without paying some of the costs of innovation and risks linked to uncertainty. In this context, low-cost tactics can avoid, at least in part, the problems facing the pioneer companies. Thus, pioneer firms will tend to develop low-cost tactics in order to take advantage of their temporary monopoly position against competitors and to strengthen their cost advantages. In this sense, low-cost tactics can lead pioneer firms to develop a strong competitive aggressiveness – low costs and low prices, allowing them access to a wide potential demand (Karakaya and Kobu, 1994), a key issue in a mature industry.4 Therefore, pioneer firms will tend to develop low-cost tactics as a way to strengthen their market position and consolidate their NPP derived from its early entry into the market. In mature industries, a greater effort to reduce costs will allow pioneer firms to promote their new products more effectively, as competition grows more aggressive with access available to a large potential demand. Therefore, firms develop low-cost tactics in order to take advantage of their PO to get NPP, avoiding some obstacles that may appear. This discussion suggests that if firms orient their PO to development of low-cost tactics, it promotes NPP, in other words, competitive tactics oriented to low cost drive PO to NPP. According to these arguments, we propose the following hypothesis:H1 The development of low cost tactics mediates the relationship between PO and NPP in mature industries.

As we indicated previously, firms will only be able to get high NPP if they guide their PO to the development of competitive tactics. Differentiation tactics – both via innovation and marketing – also drive PO to obtain NPP.

On one hand, differentiation – innovation and marketing – tactics will mediate the relationship between PO and NPP. The literature highlights that as a consequence of developing a PO, firms enjoy advantages linked to differentiation (Carpenter and Nakamoto, 1994). However, these advantages will tend to fade over time, because, as the mature industries, customers’ needs become more sophisticated and new competitors enter the market trying to exploit the potential demand generated by the introduction of new products. In this situation, pioneer firms will need and will have incentives to develop differentiation tactics.

Through the development of innovations in products and processes, firms will strengthen their market position and take advantage of attractive new opportunities (Covin et al., 2000) and help them keep abreast of changes as they occur in the market and protect, in this way, their position against potential imitators (De Castro and Chrisman, 1995). Innovation differentiation tactics will allow pioneers to enhance their appeal and reputation with customers for novelty in their products, processes and activities, which will result in achieving greater NPP (Spanos and Lioukas, 2001). Thus, in mature industries, competitive tactics oriented to innovation differentiation will drive pioneers to new product success against follower firms.

In addition, through the development of marketing differentiation tactics, firms are able to strengthen their brand image, and achieve greater customer loyalty (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998). In this sense, the development of marketing differentiation tactics becomes an essential driver to the successful exploitation of new products on the market (Hughes and Morgan, 2007). In a mature industry, these tactics will facilitate the growth of pioneers in attractive niches and allow greater contact and proximity to customers, which will allow firms a better fit to customers’ preferences and gain a greater reputation for new products (Carpenter and Nakamoto, 1994; Szymanski et al., 1995).

Therefore, firms that guide their OP to the development of differentiation tactics, will have a protection against potential imitator and will get to influence consumer preferences that will allow them to obtain profits from new products (Gotteland and Haon, 2010). Thus, only those firms that guide their PO towards the development of differentiation tactics will result in better outcomes for new products. In this line, innovation and marketing differentiation drive PO to achieve a superior NPP. In line with these arguments, we can propose the following hypotheses:H2a The development of innovation differentiation tactics mediates the relationship between PO and NPP in mature industries. The development of marketing differentiation tactics mediates the relationship between PO and NPP in mature industries.

To test the proposed model, we have developed the corresponding analysis for a sample of firms in the Spanish footwear industry, which is a traditional, mature and labour intensive industry. In 2007, according to DIRCE,5 in Spain the industry comprised 4366 firms. In order to establish the register of firms, we used different databases,6 specifically: SABI7 and Camerdata.8 Finally, after we eliminated duplicated cases resulting from the use of various sources, we had a population of 1403 SMEs.

Once we had engaged in several in-depth discussions with academics and experts in questionnaire design and conducted a pre-test with several firms, we obtained the final questionnaire, which was sent by post to the whole population, specifically with a letter to the manager of the company.9 After two deliveries and a telephone monitoring we included only the questionnaires that were complete and had been answered by the CEO. We finally obtained 224 valid questionnaires, that is, a response rate of 16.97%. The sampling error is 5.96% (for a confidence level of 95%, and p=q=0.5). In relation to the representativeness of the sample through the obtained data of SABI's population, we analysed the existence of differences between population and sample in terms of size and age by means of an ANOVA test, obtaining very similar values for both groups. Also, in order to analyse the non-response bias, we check if firms that firms that responded were different from those who did not. Thus, a t-test for all the variables between responses obtained in the first and second sending was carried out. This analysis of “non-response bias” is based on the fact that firms who respond later (sample of firms responding to the second mailing) are considered closer to the non-respondents than early responders (Amstrong and Overton, 1977). In this case, we did not find significant differences between these two groups. We have also made a comparison between the mean value of the size variable between all firms and those included in the sample. In both cases, the obtained values were similar. We did not detect a “non-response bias” (Amstrong and Overton, 1977).

MeasurementPioneering orientation: We used a three-item scale adapted from the study of Zahra (1996) in order to measure PO as a continuum. The items of this scale are very similar to those proposed by Covin et al. (2000), which have been recently used by Mueller et al. (2012). This scale reflects a way of going about making decisions and taking actions that are related to innovation (Covin et al., 2000). This scale has also allowed us to use a variable that reflects the firm's level of leadership in the product market with regard to its competitors in the industry (see Appendix A). The items reflect two primary elements of pioneering – market timing and distinctiveness – (Mueller et al., 2012). Thus, PO is a continuous variable, spreading from the pioneer to the late follower (Zahra, 1996).

Competitive tactics: To measure competitive tactics we have used the scale developed by Spanos and Lioukas (2001), which differentiates between low-cost tactics (3 items), innovation differentiation tactics (4 items) and marketing differentiation tactics (4 items). This seven point Likert scale, gathers information about the extent to which the firm develops specific competitive tactics that provide the fundamental basis for achieving competitive advantages (Porter, 1985; Spanos and Lioukas, 2001). In this study we included this classification because of its suitability for gathering the selected typology of competitive tactics, which has been widely tested.

New product performance: This construct has been measured by profitability and sales of new products, as has been done in previous studies (Zhang et al., 2009; Carbonell and Rodríguez-Escudero, 2016). Following Gupta and Govindarajan (1984), the construct has been operationalised evaluating the CEO's self-reported importance and satisfaction for each item in the last three years (seven point Likert scale). Furthermore, through SABI database, we have objective information about growth of sales and returns over investment of a total of 85 companies in the sample. We have calculated the correlations between the measures on NPP included in our study and both objective measures. We discovered that the correlations between our subjective measure of NPP and growth of sales and returns over investment were positive and significant at level of 0.01. Therefore, we have verified the reliability of our measures of performance.

Control variables: In order to control the possible effects in NPP, we included five control variables – size, age, district membership, ICT resources and organisational capabilities–. The literature reveals controversy in the relationships between a firm's size and NPP. On the one hand, the greatest size is related to NPP, by allowing firms to gain access to relevant resources to develop and take advantage of innovations. On the other hand, firms with a smaller size can generate and exploit new products thanks to their flexibility (Acs and Audretsch, 1988). The measurement of firm size was based upon the number of employees. Age of firm has also been positively related with NPP, based on the benefits of the firm's experience (Autio et al., 2000). The time span we used for age comprised the number of years since the firm's creation up to 2008. In addition, we introduce the item “availability of Information and Communication Technology (ICT) resources” as a control variable. The availability of ICT resources has a positive influence on the firms’ competitiveness, influencing both firms’ tactics and performance (Consoli, 2012). The footwear sector is an industry characterised by the existence of industrial districts, so we introduce district membership as a control variable. Traditionally, the literature of industrial districts noted the positive impact of belonging to the districts on the performance of companies that integrate them (Signorini, 1994; Molina and Martínez, 2003; Cainelli and De Liso, 2005). This is a dichotomous variable, measured through the location of the company, adopting the value 1 when the company is located in an industrial district and 0 in other cases. Finally, we introduce managerial capabilities as a control variable. This variable is linked to organisational and managerial processes and it has been measured through an item extracted from Spanos and Lioukas (2001). The resource-based view points out those capabilities can lead to a sustainable competitive advantage (Barney, 1991). Managerial capabilities are essential to increase value creation in the company (Martelo et al., 2013).

In Tables 2 and 3 we provide the descriptive statistics and the correlation matrix for all variables in our study.

Correlation matrix.

| Constructs | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PO | |||||||||

| 2. Low cost | 0.41 | ||||||||

| 3. Inn. dif. | 0.59 | 0.67 | |||||||

| 4. Mark. dif. | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.73 | ||||||

| 5. NPP | 0.22 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.38 | |||||

| 6. Age | 0.11 | −0.07 | 0.11 | 0.03 | 0.02 | ||||

| 7. Size | 0.21 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.07 | −0.08 | 0.08 | |||

| 8. TIC | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.23 | 0.34 | 0.16 | 0.06 | 0.10 | ||

| 9. District | 0.14 | 0.24 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.10 | −0.27 | −0.03 | 0.02 | |

| 10. Man. cap | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.10 | −0.26 | 0.03 | 0.25 | 0.38 |

To test the model and the hypotheses, we used the technique called Partial Least Squares (PLS), with PLS-Graph software. The particularity of this technique is based on the fact that, although it is a structural equation model it is not based on covariance but on variance, which is applied to explain the variance of the dependent variables. This is a highly appropriate technique in this case, since PLS does not require normality in the data, establishes minimum requirements on sample and scales, is more suitable for small samples and is a recommended technique to test mediation hypotheses (Fornell and Bookstein, 1982; James et al., 2006). To determine the statistical significance of the coefficients in the structural model we used a bootstrap re-sampling procedure with 500 sub-samples.

ResultsMeasurement model evaluation10With regard to item reliability, after examining the loadings (λ), we note that all the indicators used in the study exceed the recommended value of 0.7. Table 4 shows the values obtained in composite reliability (ρc), which allows us to evaluate scale reliability. As we can observe, all constructs used in the study have a strict reliability, since they have values above 0.8 (Nunnally, 1978). Moreover, average variance extracted (AVE) allows us to evaluate convergent validity. In this case, all constructs must present a value greater than 0.5 (Fornell and Larcker, 1981), so we can confirm the convergent validity of all our constructs (see Table 4).

Finally, we use the mean extracted variance to evaluate discriminate validity (Fornell and Larcker, 1981). Thus, we compare the square root of the AVE (diagonal in Table 5) with the correlations between constructs.

The square root of the AVE is greater for all the constructs than the correlation between them, indicating that each construct is more strongly related to its own measures than to others. Therefore, we can confirm the discriminant validity. Thus, following the analysis carried out we can ensure the reliability and validity of the measurement model.11

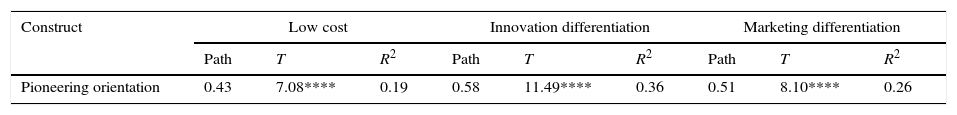

Structural model evaluationIn order to test our hypothesis, we create three models, one for each competitive tactic. The first hypothesis states the mediating effect of low cost tactics in the relationship between PO and NPP. To test the mediation hypotheses, we must fulfil the four conditions set by Baron and Kenny (1986). The first condition establishes a relationship between independent variable – PO – and dependent variable – NPP–. The results obtained (see Table 6) show that PO has a positive and significant effect on NPP. Thus, the “t” statistic shows a value of 2.81, so the results satisfy this condition (β=0.21, p<0.01).

The second condition establishes that the independent variable must have an influence on the mediator variable – low cost competitive tactics–. Table 7 shows that PO has a positive and significant influence on the development of low cost competitive tactics. This allows us, therefore, to fulfil the second condition (β=0.43, p<0.001).

The third condition establishes a relationship between mediator variable and dependent variable. The results also show a positive association between the development of low cost tactics and NPP. The data, which we show in Table 8, allows us to satisfy this condition (β=0.43, p<0.001).

Direct effect of competitive tactics on new product performance.

| Construct | New product performance | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Path | T | R2 | |

| Low cost tactics | 0.43 | 6.72**** | 0.22 |

| Age | 0.06 | 0.91ns | |

| Size | −1.06 | 1.88** | |

| District | 0.06 | 0.09ns | |

| ICT | 0.10 | 1.44* | |

| Managerial capabilities | 0.05 | 0.62ns | |

| Innovation differentiation tactics | 0.45 | 7.15**** | 0.23 |

| Age | 0.00 | 0.64ns | |

| Size | −0.17 | 2.53** | |

| District | 0.00 | 0.03ns | |

| ICT | 0.06 | 0.80ns | |

| Managerial capabilities | 0.06 | 0.81ns | |

| Marketing differentiation tactics | 0.36 | 5.37**** | 0.16 |

| Age | 0.04 | 0.54ns | |

| Size | −0.11 | 1.82** | |

| District | 0.04 | 0.55ns | |

| ICT | 0.03 | 0.37ns | |

| Managerial capabilities | 0.05 | 0.63ns | |

*p<0.10; **p<0.05; ***p<0.01; ****p<0.001.

Finally, the fourth condition establishes that the influence of the independent variable on the dependent variable must be eliminated or at least lowered when we include the mediator variable in the model. Thus, to test the mediator effect of low cost tactics in the relationship between PO and NPP we introduce this tactic and the control variables – age size, ICT resources, district membership and managerial capabilities – in the model (Fig. 2). When we analyse in an individual model these three variables, we observe that coefficient β decreases and the relationship between PO and NPP is not significant (β=0.05; compared with the original value of β=0.21). So, we can establish that low-cost tactics mediate totally the relationship between PO and NPP. Consequently, we can accept hypothesis H1.

The hypothesis H2a proposes the mediating effect of innovation differentiation tactics in the relationship between PO and NPP. As mentioned before, the first condition of mediation effect is satisfied, because PO shows a positive and significant effect on NPP. In Table 7 we can observe that PO has a positive and significant effect on innovation differentiation (β=0.58, p<0.001), so the results satisfy the second condition. Similarly, Table 8 shows a positive and significant effect of innovation differentiation tactics on NPP (β=0.45, p<0.001), so the third condition is fulfilled. For the fourth condition, we introduce, in a second model (Fig. 3), these competitive tactics in the relationship between PO and NPP. On this occasion, the coefficient β decreases (β=0.05; compared with the original value of β=0.21) and furthermore, the relationship between PO and NPP is not significant. Thus, the data show a total mediation effect of innovation differentiation tactics, so we can corroborate hypothesis H2a.

The hypothesis H2b establishes the mediating effect of marketing differentiation tactics. After the first condition of mediation effect is satisfied, we observe that results show a positive and significant effect of PO in marketing differentiation (β=0.51, p<0.001) and a positive and significant effect of marketing differentiation tactics on NPP (β=0.36, p<0.001). Likewise, we also test a third model with these three variables, again, keeping the control variables (Fig. 4). The obtained results show that the coefficient changes from a value β=0.21 to a value of β=0.05, and now the relationship between PO and NPP is not significant. So once again we obtain a total mediation effect of marketing differentiation tactics. Therefore, we can accept hypothesis H2b.

Finally, Fig. 5 shows the results obtained in the complete model, which includes PO, the three types of competitive tactics, NPP, and the five control variables. As can be observed, the model explains 26.2% of the variance of the NPP. When we analyse the impact of the three types of competitive tactics in a general model, only two – low cost and innovation differentiation – have a positive and significant influence (both p<0.001) on the NPP. The β value obtained for the innovation differentiation tactics (0.28) is higher than that obtained for the low-cost tactics (0.24). The marketing differentiation tactics show a positive but not significant influence on the NPP (β=0.06). Thus, the initially detected direct effect of PO on NPP disappears (β=0.07, non-significant, compared with the original value of β=0.21, significant) when we include the effect of the competitive tactics.12 If we multiply the significant ways, we can obtain the total indirect effect of PO on NPP through tactics, which is 0.27. As can be seen, the general model provides a significant improvement with regard to the setting of the three previous models. Thus, the R2 in the initial model is 0.090 and the R2 in the general model (with the competitive tactics) is 0.262, so there is an increase of 0.172 in R2. This increase shows that the mediator effect of competitive tactics is strong, because the obtained value for the f2 index is 0.23.13 Furthermore, the Q2 index of the dependent variable, NPP shows a positive value, therefore there is a predictive relevance for this variable in our model. Finally, in order to check the greater fit of the general model, besides the increase in R2, we have calculated the GoF index. This index of goodness of fit developed by Tenenhaus et al. (2005), arises as a result of the comparison between the technical PLS and other structural equations methods. As it happens with the R2, this index varies among 0 and 1. Although there are no thresholds of quality for this index, it is recommended to be greater than 0.31. For the general model, including the competitive tactics, the GoF index is 0.459. Thus, we note a considerable increase of fit in this model and, above all, it allows us to obtain a value above the recommended threshold.14

Finally, in order to test endogeneity problems, we have realised a different test. First, we have analysed the endogeneity in the relationship between PO and NPP through an augmented regression test as proposed by Davidson and MacKinnon (1993) and Wooldridge (2010). Also, we ran a Durbin-Wu-Hausman test. The tests failed to reject the null hypothesis of exogeneity. Therefore, the results reinforce the positive causal relationship of PO on a firm's NPP, limiting the reverse effect of the dependent variable.

Discussion and conclusionsDiscussionIn this study, we propose and test a model of the influence of PO on a firm's NPP, and how this relationship is mediated by the competitive tactics developed by the firm. First, the results obtained allow us to verify that PO has an initial positive influence on NPP. We also demonstrate that PO encourages the development of competitive tactics of low cost, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation in firms. On the other hand, we note that the development of low-cost, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation tactics positively and significantly influences NPP in the analysed firms. We detect a significant indirect effect of such PO through the competitive tactics analysed. In each of the three cases there is a total mediation effect, since the initial influence of PO on NPP vanishes when we include each type of competitive tactics in the model. These results contribute to demonstrate the influence of competitive tactics to promote success in those firms that tend to enter the market as pioneers. Thus, we find that those agile firms (Madhok and Marques, 2014) whose PO leads them to the development of appropriate competitive tactics will obtain greater performance derived from their new products.

When we observe, the results obtained in the general model we notice that PO encourages the development of the three analysed tactics. However, whereas the low-cost and innovation differentiation tactics have a positive and significant impact on NPP, the effect of the marketing differentiation tactics is positive but not significant. The results show that in order to improve the effectiveness of new products, pioneer firms direct their efforts both towards reducing costs, – in order to achieve economies of scale and cost advantages to access a large market with more competitive aggressiveness–, and towards differentiating through innovation, – adapting to customers, given their flexibility, and obtaining the income from new products as opposed to followers. However, we find that marketing efforts do not significantly affect the firm's NPP.

We consider that in the context of a mature industry, such as the footwear industry, firms can focus much of their efforts on marketing, promoting and advertising to increase demand for traditional products in new markets, thereby building on the reputation of their products. As Atuahene-Gima (1995) points out, marketing differentiation has less influence on NPP when firm introduce pioneer products, that represents radical changes to both the customers and the firm. In this sense, in these traditional markets, the firms are already widely known. Therefore, this marketing effort of pioneer firms can be inefficient in relation to the incorporation of innovation or cost reduction. In general, from the obtained results we can conclude that competitive tactics have different effects to drive the direction of the pioneers to the success of their new products.

In these types of mature industries, linkages of the pioneer with their consumers are based on the orientation of the firm towards the continuous development of innovations (Robinson and Chiang, 2002). The pioneer firms are already well known in the market, in this sense, one of the advantages of pioneers is that they “create” the market more than they enter it (Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001). Therefore, we propose that competitive tactics lead PO to NPP. Thus, the competitive tactics that determine their ability to consolidate the success obtained with a PO are the continuous development of innovations and their cost control.

Basically, the obtained results lead us to establish that firms with different levels of PO do not equally benefit from each competitive tactic option – cost leadership, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation (Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001).

These results lead to two further strategic implications. First, entry timing decision in itself is a critical decision, at both organisational and industry levels. Indeed, it is influential on subsequent tactic decisions. Secondly, the benefits of marketing differentiation have to be reevaluated.

ConclusionsThis study contributes to strengthening the link between the entry timing perspective (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998) and the competitive advantage perspective (Porter, 1985), linking competitive tactics with the deployment of isolating mechanisms to obtain and sustain effective first mover advantages (De Castro and Chrisman, 1995; Gómez and Maicas, 2011; Markides and Sosa, 2013; Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007).

The main contribution of the study is to test the mediating role of competitive tactics – low cost, innovation differentiation and marketing differentiation–, providing as it does a solid explanation of the benefits arising from the development of PO. Thus, when firms take advantage of their PO to develop appropriate competitive tactics they achieve higher NPP.

The obtained results highlight the relevance of competitive tactics to lead PO to the firm's performance, specifically to NPP (Covin et al., 2000). In this regard, we believe that the competitive advantages of low costs and product differentiation, which the literature traditionally attributes to pioneer firms, only generate and maintain if PO drives the firms to develop competitive tactics that enhance the entry and imitation barriers to achieve better NPP. Therefore, the competitive tactics of low cost and innovation differentiation play a driver role for the temporary monopoly position of pioneer firms to be effective. In this sense, one of the main contributions of the study is showing the heterogeneous effectiveness of competitive tactics developed to lead pioneer firms to obtain a high performance in their new products.

With this study, we also contribute to overcoming some of the limitations that the literature traditionally attributes to research on entry timing (Suarez and Lanzolla, 2007; Szymanski et al., 1995). In this regard, we note that we delimitate the pioneering analysis, by focusing on the firm's time of entry into the market. In this sense, we follow the recommendations of different authors (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998), and focus on the market pioneer, differentiating it from other figures (product pioneer and process pioneer), which some studies confuse with the market pioneer and hence create confusion in the results obtained. On the other hand, we define PO as a continuous variable spreading from the market pioneer to late follower (Mueller et al., 2012). Another contribution of this paper is that, considering the restrictions on the choice of market share as the only variable to measure firm's performance, we use a measure of NPP which includes both sales and profitability items. In addition, we establish the extension of the temporary horizon of measure to three years as an approximation to the sustainability of performance.

LimitationsWe acknowledge several limitations. Firstly, this is a cross-sectional study that has been developed in only one industry. This limitation is quite frequent in entry timing studies and may condition the validity of the obtained results, as such and as Lieberman and Montgomery (2013) established, the first mover advantages obtained in a specific industry15 can change over time. In this sense, Gómez et al. (2016) establish that certain industry dynamics such as market growth and technological discontinuity affect first mover advantages in terms of profitability and market share. In this sense, we consider that the variety of data included in the study proved a longitudinal approach to be very complex. Furthermore, solely the cross-sectional approach to achieve the proposed aims was utilised and it has often been used in studies on entry timing previously (Wiklund and Shepherd, 2003).

Furthermore, another limitation would be the possible mismatch between the CEO's perceptions and the objective reality. Following Spanos and Lioukas (2001) managerial perceptions have a huge influence on shaping the extension of the firm's behaviour. In this respect, we can justify the use of these subjective measures of performance.

Managerial implicationsFrom the conclusions, we can draw several implications for managers. In this regard, we believe that those firms entering the market as pioneers should seek to consolidate the advantages of the first entrant, adopting tactics to strengthen their cost and differentiation advantages in order to guarantee new product success. In this sense, from the information obtained in interviews with the managers as well as the results of the study, we can establish that in mature industries such as the footwear industry, in which there is a high competitive rivalry, pioneer firms must combine a continuous effort in cost reduction and the incorporation of product and process innovations to ensure high NPP. Thus, we encourage managers of the pioneer firms to direct their efforts to the development of competitive tactics of low costs, which will help them to consolidate their first mover advantages and compete with their new products in advantageous position relative to competitors. In addition, the managers of the pioneer firms in mature industries should also direct their efforts to the development of innovation-oriented tactics. In this way, the consumers will perceive the innovative nature of the products and they will be converted into references with which the rest of products introduced to the market at a later moment will be compared. However, as we have explained previously, the managers of pioneer firms should monitor the effectiveness of marketing efforts. Thus, as has been discussed previously, the marketing differentiation tactics could pose as more suitable for follower companies. The identification of these effects should help managers and stakeholders to make more effective entry decisions to sustain a firm's advantage, leading to a better NPP.

Future researchThe results obtained lead us to propose several lines of research. A possible extension of this paper would be to develop a longitudinal study to analyse how the industry dynamics conditions the evolution of first mover advantages over time (Gómez et al., 2016) or to take a context-oriented approach (Bamberger, 2008). Likewise, it would be interesting to conduct research that focuses on the development, launch and performance of specific products, noting the competitive tactics related to them. We also suggest incorporating how certain environmental conditions, such as dynamism or hostility (Lindelöf and Lofsten, 2006), affect the mediating role of each type of competitive tactics in the relationship between PO and firm's performance.

AknowledgementsThe authors are grateful to Lucio Fuentelsaz, Davide Consoli and José Emilio Navas-López, and to several participants at various conferences for their helpful comments. This research was supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness of Spain- ERDF [Project: ECO2013-42387-P and ECO2016-75781-P].

| Dependent variable | |

| New product performance (Gupta and Govindarajan, 1984; Zhang et al., 2009) | |

| Importance (Cronbach's alpha=0.909) | Satisfaction (Cronbach's alpha=0.928) |

| Importance of Profitability of new products | Satisfaction for Profitability of new products |

| Importance of Sales of new products | Satisfaction for Sales of new products |

| Independent variables | |

| Pioneering orientation (Zahra, 1996: Cronbach's alpha=0.958) | |

| This company is usually among the first to introduce new products to the market | |

| This company is this industry's leader in developing innovative ideas | |

| This company is well known for introducing breakthrough products and ideas | |

| Competitive tactics (Spanos and Lioukas, 2001) | |

| Innovation differentiation (Cronbach's Alpha=0.908) | |

| Expenditure on research and development for product development | |

| Expenditure on research and development for process innovation | |

| Emphasis on going ahead of competition | |

| Proportion of product innovations | |

| Marketing differentiation (Cronbach's Alpha=0.897) | |

| Innovations in marketing techniques | |

| Emphasis on the organisation of marketing department | |

| Expenditure on advertising and promotion | |

| Proportion of product innovations | |

| Low cost (Cronbach's alpha=0.849) | |

| Modernisation and automation of the production process | |

| Efforts to achieve lower costs per product with the increase of production | |

| Utilisation of productive capacity | |

According to Mueller et al. (2012), literature has emphasised pioneering as a specific exhibition of proactive behaviour. Thus, proactiveness encompasses a host of other behaviours as well and in doing so captures much more than PO. Proactiveness is an entrepreneurial orientation dimension, refers to a future perspective where firms try to develop new products, services, administrative technics, operating technologies or improvements on them, anticipating changes that arise in the environment (Covin and Slevin, 1989; Hughes and Morgan, 2007). From this perspective, the influence of PO upon firm performance can be lost among the commingling of proactiveness and the effect of PO may be overlooked in a broader analysis using proactiveness (Mueller et al., 2012).

Traditionally, the performance advantages of the pioneer have been measured by the market share of the firm, which is a bias in many studies of entry timing (Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998). In order to correct this bias, new performance measures are incorporated, as growth of sales, return of assets, profitability over investment, growth of margins, among others (Durand and Coeurderoy, 2001; Gómez and Maicas, 2011; Lieberman and Montgomery, 1998). Several studies from the marketing literature highlight the interest of focusing on the influence of entry timing on new products performance (Golder and Tellis, 1993; Robinson and Chiang, 2002; among others). Some articles propose combining measures of growth of sales and profitability relative of new products to avoid further biases (Zhou, 2006), as we do in this study.

As opposed to the risks initially established by Porter (1985) on the difficulties in achieving a successful balance of low cost orientation and differentiation orientation, we maintain that low cost tactics, innovation differentiation tactics and marketing differentiation tactics are compatible in facing up to competitive forces (Wright et al., 1995).

In mature industries, as the footwear industry, albeit unhampered by strong entry and imitation barriers, resource position barriers can be established, which favour a firm's expectations of obtaining FMAs (Makadok, 1998).

Central directory of Spanish firms.

We established the condition of not including in this study those companies that had less than five employees. This is because these firms can present characteristics substantially different with respect to the considerations detailed in the theoretical sections lacking the same operating structure and hence requiring a specific study (Spanos and Lioukas, 2001).

SABI is a database of Spanish and Portuguese firms that includes economic and financial information.

Camerdata is a database that combine a directory of all Spanish companies from the local Chambers of Commerce.

Despite the questionnaires were sent to the manager of the company, when the questionnaire had been filled we asked the respondent to report the person who answered the survey. Thus, those questionnaires that had not been filled by the manager were eliminated. Therefore, the managers who responded to the survey were CEOs, what allows us to have security that they have an overview of the company and have a deep knowledge of the operation of the company, so they can adequately answer the questionnaire. Anyway, the questionnaire was sent with a letter in which we explained those concepts that we believed may cause doubt. They also were offered an e-mail address and a phone contact to solve any doubt thereon. Likewise, the development of the pre-test prior to the survey with several managers allowed us to check if they had enough knowledge and allowed us to adapt those parts of the survey that could create a problem.

Before performing any further analysis, in order to check that there were not problems of multicollinearity, we analysed the VIF factors and the condition indexes. After these analyses, we can conclude that there are no multicollinearity problems among the variables included in the study since the VIF index does not exceed for any variable the value 5 recommended in the literature. In addition, the condition indexes are all under 15. Therefore, we can discard the existence of multicollinearity problems between the variables.

In order to improve the rigour of testing in the measurement model we have included a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The results of the CFA suggest that our measurement model provides a good fit to the data on the basis of a number of fit statistics. NFI: 0.901, NNFI: 0.906, CFI: 0.915 and IFI: 0.916. Therefore, the measurement model was accepted as a number of tests were conducted to assess its reliability and validity.

In order to provide robustness to the obtained results, we have replicated the model with a sample of firms and with an objective measurement of performance – sales growth–. The obtained results show, also in this case, that competitive tactics totally mediates the effect of PO on sales growth.

f2=Rincluded2−Rexcluded2/1−Rincluded2; f2>0.02 weak effect, f2>0.15 strong effect, f2>0.35 very strong effect.

Although the GoF index gives us indications of a good model fit, we have developed the EQS test to confirm the validity of our structural model. The obtained results in the confirmatory test of the structural model with EQS show higher indicators than those obtained in the CFA. It demonstrates the nomological validity of our model. Thus, the obtained results were as follows: NFI: 0.920; NNFI: 0.941; CFI: 0.954 and IFI: 0.954. Therefore, we can establish that the tests performed show the high validity of our structural model.

From this study, we cannot extract clear conclusions on whether the footwear industry is a special case with regard to the obtaining of first mover advantages. Additional theoretical developments and empirical analyses in different industrial contexts could help us to shed some light on this.