In the current economic context where the behaviour of firms is carefully examined by the markets, the corporate reputation which is generated by organisations among their stakeholders may facilitate their success. Since employees are actively involved in its shaping and influence the overall perception of the firm's corporate reputation, the aim of this research is to improve the management of the employee views of reputation in order to increase its global evaluation. To do this, we analyse whether the existence of a characteristic management style influences the employee views of reputation, studying the effect of control variables such as employee age, gender, level of education or job position. Using a sample of 148 employees of Spanish accounting audit firms, we develop a specific tool for measuring the reputation from the employee perspective of service SMEs, as well as confirming that a strong participative management style promotes a better perception of reputation by employees than a competitive style. Hence, this study reflects that men prefer a competitive management style. Also, a high level of education along with job position has a positive impact on the preference of a participative style with the job position being the main moderating variable of the proposed model.

In recent years, the global financial system has been shaken by the biggest wave of financial scandals in U.S. and Europe, including Spain. This has led to a deep crisis of confidence in the whole control system of information transparency offered by all the companies, especially those that receive the savings of citizenship (García Benau and Vico Martínez, 2003). Indeed, the auditing sector has been one of the most damaged due to tighter control standards (Ruiz-Barbadillo et al., 2000; Carrera et al., 2007) and the bad reputation of their audited companies, having a direct impact on their professionals (Humphrey et al., 2009).

Since reputation is an intangible asset source of competitive advantage that ensures the development and survival of firms (Martínez León and Olmedo Cifuentes, 2010), professionals and academics have increased their interest in it, reflecting the critical role that reputation has in business management (Chun, 2005). Furthermore, it has become a key objective in the audit industry, because customers and users of these companies may be very sensitive to reputation. In this sense, firms more visible in the capital markets tend to be more concerned about engaging highly reputable auditors, consistent with such firms trying to build and preserve their own reputations for credible financial reporting (Barton, 2005). Another aspect to take into account is the way in which these companies are managed because it reflects their corporate reputation. Thus, the management style developed should be analysed. Finally, we must not forget that the fees that firms can earn are determined by the reputation that they have with consumers (Moizer, 1997), influencing their customer engagement and business results.

Traditionally, all the tools and studies have measured perceived corporate reputation through external stakeholders (customers, financial analysts, managers of other companies and society in general, among others) using the tools of Fortune, Reputation Institute (RepTrak) or Merco (in Spain). Indeed, the first academic approaches to the analysis of reputation in the field of auditing (Moizer, 1997; García Benau et al., 1999; Moizer et al., 2004) have focused on the study of the reputation and image of the auditors from the point of view of their customers (the audited companies). However, there is an important gap in the study of reputation from the view of employees and their influence in shaping the corporate reputation of the firm, since this group is the most influential in the perception of corporate reputation of external stakeholders. As audit firms are labour intensive services, the previous influence of employees is stronger (Helm, 2007; Davies et al., 2010).

This research focuses on the study of the employee views of reputation in SMEs audit firms and how to improve it as a previous and necessary step in the configuration of the reputation of the organisation, given the important role that this collective plays. In addition, the leadership style developed by their managers in the company is studied from the employee perspective.

Thus, the aim of this research is to analyse how the management style of senior management influences the employee views of reputation, given that it is strongly influenced by the personal and social identity of both groups. To get this, the paper is structured as follows. First, we review the literature about corporate reputation, identity and image, highlighting the important role of employees in its configuration. Next, we study the managerial styles, describing their different typologies. From this review, we establish several hypotheses that are empirically tested in audit firms that operate in Spain, including four control variables related to organisational staff (age, gender, level of education and job position), by using a path analysis whose estimation is developed by using AMOS 18. Several results are obtained and widely discussed including the most significant conclusions in the last section of this paper.

Corporate reputation and its estimation in audit firmsAlthough reputation is a term used in several disciplines (Fombrun and Van Riel, 1997; Arbelo Álvarez and Pérez Gómez, 2001; Rindova et al., 2005), all of them agree that it is a perception which develops over time (Weigelt and Camerer, 1988; Podolny, 1993; Fombrun, 1996), and reflects the evaluations that different stakeholders, both internal (managers, employees) and external (consumers, users) (Fombrun and Shanley, 1990; Chun, 2005) have of a company. Additionally, reputation is compounded by a set of dimensions (Weigelt and Camerer, 1988; Dollinger et al., 1997; Ferguson et al., 2000), which will be discussed in section ‘Dimensions of corporate reputation’.

Thus, reputation is defined as ‘a perceptual representation of a company's past actions and future prospects that describe the firm's overall appeal to all its key constituents when compared to other leading rivals’ (Fombrun, 1996: 72). In this line, Gotsi and Wilson, 2001 understand reputation as ‘a stakeholder's overall evaluation of a company over time’, and this evaluation is based on the stakeholders’ direct and indirect experience with the company. Therefore, most authors agree that reputation is the ‘global (i.e., general), temporally stable, evaluative judgement about a firm that is shared by a multitude of constituents’ (Highhouse et al., 2009a,b: 1482). In this line, the authors Weiss et al. (1999: 75) understand reputation as ‘a powerful global perception by which an organisation is helped to achieve higher estimates or respect’.

However, the study of reputation in the field of audit firms has not always been supported on previous conceptualisations based on organisational perspective. Several studies in auditing use corporate image and corporate reputation as synonyms, and both have been used as a proxy for the quality of audit service (García Benau et al., 1999; Moizer et al., 2004; Cameran et al., 2010a,b). That is why both terms are differentiated from an organisational perspective of reputation (Villafañe, 2004) in the next section. In any case, other research has shown that customers tend to rely more on the social status of the audit firm than on the quality of their work (Rao et al., 2001), because they are unable to evaluate in its entirety.

In general, the reputation of the audit firms has been studied from a financial perspective, through (Moizer, 1997): (a) the audit fees, (b) the value of the shares of the audited customers, and (c) the effects of changing auditor to the audited company. In addition, several financial indicators of the audits (assets, leverage, ROA) and its customers (new value of their shares after changing of auditor) have been used to estimate the image (Srinivasan Krishnamurthy et al., 2006; Weber et al., 2008).

In any case, all these studies have been developed from the external perspective of investors or customers (CFOs of audited companies). However, the objective of this research is to study the reputation from an internal viewpoint of the audit firm, as the offered by its employees.

Relationship among corporate reputation, identity and imageTo analyse the relationship between these three concepts it is essential to consider that reputation is the judgement or evaluation that is made of the behaviour of the firm (audit), from its identity and image (Davies and Chun, 2002). Both terms refer to the public perception of a certain organisation (Gotsi and Wilson, 2001), being important to define each one and highlight the main differences among them and how they relate to each other.

Corporate IdentitySelame and Selame (1988) define the identity of a company as the visual expression of the organisation, according to the vision it has of itself and how it likes to be seen by others. Therefore, it is a symbol that reflects the way the company wants to be perceived (Mínguez Arranz, 2000). This corresponds to the three dimensions of identity described by Sanz de La Tajada (1994): (a) what the company is; (b) what the company says of itself; and (c) what the public believes the company is.

In this sense, Sanz de La Tajada (1994) specifies that identity is defined by two types of traits: (a) physical, i.e., icon-visual elements such as logo, brand or external signs that allow the firm to be recognised by different groups of people (Dowling, 1994) and (b) cultural, such as organisational values and beliefs that members have of the firm (Whetten and Mackey, 2002). Hence, identity is projected in four different ways (Mínguez Arranz, 2000; Chun, 2005): who the organisation is, what it does, how it does (it) and where it wants to go. These projections are manifested in four visible areas: (a) products and services, about what the company makes or sells; (b) the environment, referred to the place or places where the activity is developed; (c) communications, about how the firm explains what it does to their stakeholders; and (d) the behaviour of the company with its employees and its environment (Mínguez Arranz, 2000).

Therefore, corporate identity refers to the set of visual, cultural, environmental and behavioural aspects that are shared by a group of individuals and have a differentiator and strategic value (Mínguez Arranz, 2000), representing what the company has chosen to be (Arbelo Álvarez and Pérez Gómez, 2001).

Consequently, reputation collects all attributes or specific aspects of identity, giving them a long-lasting effect because they are created within the organisation (such as organisational history, strategy or business plan, and organisational culture). This allows the audit firm to be recognised by different stakeholders.

Corporate imageThe corporate image may be defined as the overall impression (beliefs and feelings) that an organisation creates in the minds of their audiences (Dowling, 1994) in terms of what the company says about itself and what the people say about the firm (Arbelo Álvarez and Pérez Gómez, 2001). Image configuration is influenced by the projection that members of the organisation make of it, because it influences the perception that external stakeholders have of the company (Bromley, 2000). Image is constructed through (Capriotti, 1999): (a) communications in massive media, as commercial messages and other information controlled by the organisation; (b) interpersonal relations, in terms of the influence of reference groups and opinion leaders; and (c) personal experience that stakeholders have with the company. In the case of audit firms, the latter two are more important, as the media communications of the audits are limited by Spanish law.

Thus, Sanz de La Tajada (1994: 131) defines corporate image as ‘the set of mental representations, both emotional and rational, that an individual or group of individuals associated with a company have, as a result of the experiences, beliefs, attitudes, feelings and information that this group of individuals perceived the company’. That is, the ideas used to describe or remind the firm, in this case to the audit.

Consequently, the corporate image is built from corporate identity (physical and cultural traits), and reflects the personality or way of operating that is perceived by external stakeholders regarding the organisation. Therefore, image is a reflection of identity, whose final destination is to achieve a positive public attitude towards the audit. The consolidation of the positive or negative image that the firm develops over time (Villafañe, 2004) is a part, in turn, of corporate reputation, as shown in Fig. 1.

In this sense, Arbelo Álvarez and Pérez Gómez (2001: 5) determine that ‘reputation is the sum of the identity, image, perceptions, beliefs and experiences’ that stakeholders link ‘in the long term with the company, involving practically all the organisation’.

Employee views of reputation: a reflection of corporate identity and corporate imageAs mentioned above, the identity and the image are part of the perceived corporate reputation. The aim of this section is to highlight the importance of employees in the determination of these three concepts, justifying the need to study their perspective in audit firms.

The identity of the audit is formed by its internal stakeholders, where employees have an important role because they determine and disseminate what the company says about itself. Employees are participants of cultural traits that define the identity of the organisation (Sanz de La Tajada, 1994), especially in terms of their behaviour. Their beliefs about the firm also explain its identity as proposed by Whetten and Mackey (2002).

Another perspective is how employees affect the corporate identity that the audit shows outside both when providing its services and in the environment in which they operate, in the form of communicating it and, especially, in their behaviour with other stakeholders (Davies et al., 2010; Helm, 2011). Therefore, the employee is a fundamental subject in the definition and dissemination of corporate identity.

The corporate image matches the external perception of the audit, with employees being the key actors on its configuration because their impressions (views and beliefs), result of their experiences, attitudes, feelings and information, are transferred to other stakeholders with which the firm interacts (Davies et al., 2010; Helm, 2011), generating a set of interpersonal relationships (Capriotti, 1999).

Consequently, if the reputation includes the evaluation of identity and image of the audit and employees are a significant part of both, they are therefore determinants of global reputation of the audit firm. Thus, we can say that employee views of reputation are the result of corporate identity and image that, in turn, are influenced by their personal and social identity. In fact, according to Arbelo Álvarez and Pérez Gómez (2001), how employees see the company reflects what they will say about it to other stakeholders, determining the external reputation of the audit. For all these reasons it is considered necessary to study the perception of the reputation of an audit from the perspective of their employees.

Dimensions of corporate reputationFollowing the study of corporate reputation from an organisational approach, identifying the different dimensions that make up the concept according to the literature is necessary. With reference to this, several tools have been used to measure reputation. Their analysis allows one to compare the views that stakeholders have of a company, and adopting the best standards and determining dimensions of this intangible asset. There is clearly a triple perspective study (Martínez León and Olmedo Cifuentes, 2009; Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León, 2011): (a) conducted by prestigious institutions, supported by the contributions of Fortune, Financial Times, Reputation Institute, and Merco; (b) developed in a academic field, with the work done by Peters and Waterman (1982), Caruana and Chircop (2000), Cravens et al. (2003), De Quevedo Puente (2003), Helm (2005, 2007, 2011), and López López and Iglesias Antelo (2006, 2010), among others; and (c) exposed especially in the area of audit firms, which include investigations of Moizer (1997), García Benau et al. (1999), Moizer et al. (2004), and Cameran et al. (2010a,b). In particular, Moizer (1997) argues that reputation is a multidimensional construct, where the causal line between the quality of the audit work and the audit firm's reputation is very thin due to the intangibility of the service. Therefore, an audit's reputation is not determined primarily by the quality of service, but how the firm is generally seen (especially by the financial community). Consequently, other dimensions to measure the reputation of these companies should be considered including their human resources (García Benau et al., 1999). It is also important to note that most studies about reputation in auditing have been based on Moizer's ideas (1989) (Cameran et al., 2010a,b), not taking into account the organisational perspective that is used here.

In fact, the reputation dimensions of the tools and researches not conducted in auditing were determined from an organisational perspective, as proposed in this research. Thus, Table 1 shows the main dimensions, its conceptualisation and the work behind them. Consequently, in the field of accounting audit firms, as well as including the provision of services and human resources, it also seems appropriate to consider other dimensions to analyse its impact.

Dimensions of corporate reputation from the organisational perspective.

| Dimension | Importance for corporate reputation | Authors that proposed the ideas | |

| Financial position and value creation | Its greater assessment implies a major reputation for the company. | - Fortune- Reputation Institutea- Merco- Weigelt and Camerer (1988)- Fombrun and Shanley (1990)- Dollinger et al. (1997) | - Caruana and Chircop (2000)- Mínguez Arranz (2000)- Cravens et al. (2003)- Iglesias Antelo et al. (2003)- Helm (2005, 2007) |

| Human resources | They constitute a stakeholder group itself and their perception and relationship with other stakeholders (suppliers, customers…) is going to influence these last. | - Fortune- Reputation Institutea included in Fombrun (1996), Fombrun et al. (2000) and Fombrun and van Riel (2003)- MERCO- Villafañe (2004)- Caruana and Chircop (2000) | - Peters and Waterman (1982)- Cravens et al. (2003)- De Quevedo Puente (2003)- Helm (2005, 2007)- Martín et al. (2006)- López López and Iglesias Antelo (2006) |

| Management quality and managerial ability | The knowledge, skills and attitudes of managers in corporate governance have an impact in the company's visibility in the environment (external reputation) and influence directly the perception of internal stakeholders (internal reputation). | - Fortune- Reputation Institute with RepTrak- MERCO- Mínguez Arranz (2000)- De Quevedo Puente (2003) | - Dollinger et al. (1997)- Caruana and Chircop (2000)- Villafañe (2004)- Helm (2005, 2007)- Martín et al. (2006) |

| Business leadership | The degree of admiration and feeling that the organisation causes have an effect on its reputation. | - Financial Times- Reputation Institutea- Mínguez Arranz (2000) | |

| Ethics, culture and corporate social responsibility | All of them have an influence on the organisational behaviour and functioning, affecting reputation. | - Fortune- Financial Times- Reputation Institutea- MERCO- Fombrun et al. (2000)- Villafañe (2004)- Cravens et al. (2003)- Helm (2005, 2007) | - Peters and Waterman (1982)- Weigelt and Camerer (1988)- Fombrun and Shanley (1990)- Villafañe (2004)- Iglesias Antelo et al. (2003)- López López and Iglesias Antelo (2006)- Martín et al. (2006) |

| Products and/or services | Customers, as stakeholders, assess the overall reputation of the organisation according to their experience or knowledge about the products and/or services offered by the company, so that the more positive is that perception, the greater reputation the company has. | - Reputation Institutea- MERCO- Caruana and Chircop (2000)- Mínguez Arranz (2000) | - Cravens et al. (2003)- Helm (2005, 2007)- Martín et al. (2006) |

| Brand image | Its consolidation in the long term generates reputation. | - Mínguez Arranz (2000)- Chun (2005) | - Helm (2005, 2007) |

| Innovation | It affects both products and services, as processes and systems that improve the competitive position of the firm and its reputation. | - Fortune- Financial Times- Reputation Institutea- MERCO- Villafañe (2004) | - Cravens et al. (2003)- De Quevedo Puente (2003)- López López and Iglesias Antelo (2006)- Martín et al. (2006) |

Among the many existing tools to measure the reputation from organisational approach there are very few adapted to SMEs, particularly in the audit industry. The developed approach in this sector has two orientations: (a) the level of the audit fees reflect their reputation (Wilson, 1983; Moizer, 1997); and (b) the reputation depends not only on the quality of service, but also on its staff or its customers (Moizer, 1997; García Benau et al., 1999). Thus, other organisational variables that have been gaining importance recently, such as ethics, corporate social responsibility, leadership or quality of management and managerial ability have not been considered. This gap has been covered by works such as Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León (2011) that developed a tool to measure the reputation of service SMEs, according to the results obtained from a Delphi methodology. It was elaborated with the collaboration of 16 experts from academia and the service industry, being later adapted to the audit firms (Martínez León and Olmedo Cifuentes, 2012).

Following this proposal, reputation is determined from eight dimensions (Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León, 2011): Financial position and value creation; Human Resources; Quality management and managerial ability; Business leadership; Ethics, culture and corporate social responsibility (CSR); Products and/or services; Brand image, and Innovation, and their respective attributes (25 in total). For employees, the main dimensions of reputation to evaluate are (Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León, 2011): Human Resources; Quality management and managerial ability; Business leadership; Ethics, culture and corporate social responsibility (CSR); and Innovation, along with the assessment of customer loyalty, as a representative item of the dimension Products and/or services.

Management style: an identity traitThe manner in which the managers of a company manage and control their employees depends largely on their attitude and leadership over the latter, and their perception of corporate identity and image that reflect in the organisational culture. For this reason Dowling (1994) recognises that the management style determines the vision of the organisation as an important step in the management of the image. In addition, managers must work to build a positive reputation as a prerequisite for the development of a successful organisation (Markwick and Fill, 1997), where employees are satisfied and motivated to work.

However, the existence of a gap between perception and reality of reputation requires that managers have information to remove it and promote the improvement of the outcomes and the strategic management of the firm. Such information would affect the shared identity and image, allowing communicating to employees that their performances are well received because they are a relevant interest group for the organisation (Markwick and Fill, 1997). That is why management style includes values and patterns of behaviour in which the management of a company is based on, in order to influence the behaviour of the rest of the organisation.

The management style has been a forgotten area of research in economic literature (Del Brío González and Junquera Cimadevilla, 2002), which has recently begun to develop, especially by its close relationship with organisational culture (Bititci et al., 2006), where the management style is a key element to understanding the culture of an organisation (Schein, 1985; Pheysey, 1993; Cameron and Quinn, 1999). As a result, each type of organisational culture has a predominant management and leadership style (Cameron and Quinn, 1999).

Therefore, both concepts, management style and organisational culture, are aligned to further their study (Bititci et al., 2006). Harrison (1987) suggests four types of organisational culture, based on the work of Hofstede (1980), which link organisational culture types (role culture, power culture, achievement culture and support culture) with management style. Following this idea, the model of Cameron and Quinn (1999) is the one that pays special attention to the management style as a configurative element of organisational culture (Olaz Capitán and Ortiz García, 2009). Thus the clan culture is based on a management style where the consensus and participation in a firm is essential in order to look for the best teamwork. To get it, a high commitment, loyalty and trust have to be encouraged among the members of the firm. That is why this management style is considered participative.

In the so-called adhocratic culture, management style is characterised by the permanent coexistence of risk in decision making, the creativity, innovation and a wide margin of manoeuvre in the actions of staff. It is an innovative management style.

In hierarchical culture, management style is directed to job security, permanence in the job position and the reduction of uncertainty as the basis for the functioning of the organisation; thereby a conservative management style is followed.

Finally, market culture develops a management style that promotes the aggressiveness of its members against changes in the environment as a way to reach the established results on time because the continuous improvement of the established goals is promoted. In this case, a competitive management style is developed.

Anyway, management styles are a reflection of the identity of the firm, because the behaviours and ways of running the company integrate a part of the cultural traits that define the identity (Sanz de La Tajada, 1994; Whetten and Mackey, 2002). Furthermore, the manner by which the company operates together with the behaviour that it has towards their employees is two ways to project its corporate identity (Mínguez Arranz, 2000; Chun, 2005).

Influence of management style on reputationAs stated previously, the corporate identity is a part of the company's reputation. Therefore, if the management style is one of the different ways to create and reflect the identity of a company, it also has an effect on reputation.

Starting with the idea that reputation is a view that members of an organisation reflect in and out of, and focusing on the view that employees’ have of their company, the management style developed within the firm can be a trigger of the more or less favourable employee views of reputation. That is, certain management styles will promote different views of reputation.

Despite the existence of different management styles, in this research we analyse two: participative and competitive, since they represent very different cultures, even antagonistic, reflecting different organisational identities. This fact has also been revealed in the empirical study, since both management styles are uncorrelated, which is not what happened with the rest.

The participative management style refers to the attitude of a superior that, except in unusual circumstances, makes decisions by consensus and sets organisational goals only after all involved members are consulted and their opinions are thoroughly considered (Miah and Berd, 2007). This management style balances the involvement of managers and subordinates in information processing, decision-making, problem solving (Wagner, 1994) and the functioning of the company, so there are greater customer orientation and innovative behaviours that facilitate organisational changes (Pardo del Val and Martínez Fuentes, 2004).

Thus, managers share the decision-making process with the rest of the members of the organisation, not just those who are formally authorised to do it, which involves establishing a system of information, training, rewards, authority delegation, and a characteristic leadership style and culture. This reality creates better intrinsic motivation of the staff, which helps them perform better and feel good in their job positions (Kim, 2002), being beneficial to their mental health and job satisfaction (Spector, 1986; Miller and Monge, 1986; Fisher, 1989). In fact, some researches have shown how participative management style has positive effects on employee satisfaction (Drucker, 1974; Likert, 1967; Bernstein, 1993; Kim, 2002).

The competitive management style is focused on each organisational member having to reach the completion of a certain task or goal, reducing the communication with the rest (Somech et al., 2009). Teamwork has a poor performance as a result of: (a) the lack of confidence among its members, because the ideas and resources of others are not shared, information is hidden and the efforts of others are blocked; and (b) the disruptions in communication and exchange of ideas (Somech et al., 2009). Thus, the morale of the group and its relationships are less important for this style of management (Cuadrado, 2001). Employees are more oriented to individual results that they must achieve and the rewards that it brings them, instead of the collaboration and involvement with other organisational staff. However, the degree of commitment to the objectives, according to the associated rewards with their achievement, makes employees become integrated into the organisation in order to perceive its functioning. Therefore, this knowledge will have some effects on the configuration of the reputation of the firm.

To sum up, the participative style is more democratic and focused on relationships, while the competitive style is more autocratic and task-oriented (Cuadrado, 2001). However, this latter style does not mean that there is no innovation behaviour among employees, because many times it will be necessary to achieve the agreed or imposed objectives (in this case, as a result of a more authoritarian style).

Model and hypothesesInfluence of management styles on employee views of reputationAfter reviewing the literature, it has been inferred that the management style developed by the senior management of a firm acts as an antecedent of the employee views of reputation, so the types of management styles that have more influence on reputation are explored.

First, participative management style is based on teamwork, consensus and participation of employees, forcing organisational staff to be more involved in the running of the company. This will require them to: (a) think strategically (Pardo del Val and Martínez Fuentes, 2004), encouraging their participation in the formulation and implementation of competitive strategy; (b) be involved in decision-making, not only strategic decisions, but also tactical and operational ones, claiming an updated vision of the internal and external situation of the organisation; (c) be personally responsible for the quality of their own work (Bowen and Lawler, 1995), because it allows achieving the established collective objectives and strategies, improving the functioning of the company (Hermel, 1990); (d) take appropriate action to satisfy the customer (Bowen and Lawler, 1995), meeting their needs and expectations, and guiding the activities of the company to them; and (e) have a commitment and self-control (Lawler, 1993).

In addition, employees are major recipients of knowledge of external information sources and a participative decision making improves the introduction and evaluation of more ideas in this process. In this sense, participative management style aims to promote the flow of ideas from abroad (Hafkesbrink and Schroll, 2009).

Consequently, the improvement of the view of the company's activity from their own employees has an effect on their involvement, the fostering of their personal fulfilment, their identification with the audit and their work in it, their sense of responsibility and their interaction with the outside. Therefore, they have a greater awareness of the importance of the reputation for the company and the need to contribute to their proper configuration, even interacting with external stakeholders to improve it.

In addition, participative management style improves job satisfaction (Kim, 2002), intrinsic motivation, productivity, creativity and the development of initiatives, reducing inter-group and intra-group conflicts and staff turnover (Rodríguez Pérez and Van de Velde, 2005). It encourages innovation, problem solving throughout the organisation (Lawler, 1993) and change management (Pardo del Val and Martínez Fuentes, 2004), getting employees more motivated and involved in introduce novelties (Quinn and Spreitzer, 1997). All of this increases the positive views of reputation of employees.

Thus, this management style among employees creates a greater view of the importance of reputation for the firm, and a more positive view of reputation, establishing the following hypothesis:H1 Employees that work under a participative management style have a better (higher) perception of reputation.

In the case of competitive management style, it is focused on achieving a task or goal, where employees concentrate on its achievement and worry about the reward they are going to obtain, reducing collaboration, communication and involvement with other members of the company and weakening teamwork and the development of dialogued solutions (Somech et al., 2009). Its impacts on employees are: (a) a clear focus on the goals or tasks to achieve; (b) a high motivation and interest in the pursuit of these objectives; (c) a limited interaction with other organisational staff; (d) a little exchange of ideas with others (Somech et al., 2009); and (e) a moderate self-control, because it is necessary to have continuous monitoring of their behaviour, to not breach the moral and ethical principles of good governance (Cuadrado, 2001).

Along with the above, the employee is neither involved in the formulation and implementation of organisational strategy, nor in making strategic, tactical and operational decisions, but is willing to meet the interests established by the organisation. This is why they have to share the required corporate identity which facilitates their interest in building the perception of the reputation that the company wants.

Since employees make an effort to combine the most organisational success with the professional and personal, and they have no decisive support of the other staff and managers, they will be very concerned about their reputation as employees and the reputation of the organisation where they work for, because this and the achievement of the objectives are going to determine their tenure in the company. As well, at the time of leaving the company, the reputation of the firm where they work and their own reputation are highly valued in the labour market.

Consequently, the competitive management style means for employees a sense of competition and dependence on their superiors that influence their views of the firm reputation and its culture. Thus, the more competitive the management style, the more increased view of the firm's reputation will have employees. We therefore propose the following hypothesis:H2 Employees that work under a competitive management style have a better (higher) perception of reputation.

Therefore, this research suggests that the consolidation of certain management styles, as proposed in the hypotheses, influence better employee views of reputation and can be used as a strategy to build a stronger internal reputation and its proper management.

Influence of control variables on employee views of reputationThe study of corporate reputation would not be completed if the role of other relevant variables in shaping the views and attitudes of employees are not analysed, i.e., personal characteristics. Some control variables are considered in this research to provide a better understanding of the assumptions made. Their inclusion is justified by previous researches, as developed by Ou (2007), who included in his study of reputation from the customer perspective the variables age, gender, income and education. In this research, taking into account the employee perspective, the control variables included are age, gender, level of education and job position.

The study of age as a control variable is justified by the diversity of the staff that work in a company. The age implies a lifetime experience (personal and professional) and a process of socialisation of the employee which may be related to their perception of reputation. This variable has also been studied in subjects linked with the reputation as the formation of the image (Baloglu and McCleary, 1999), because image is formed from personal factors, stimulating factors and consumption patterns of customers (González-Benito et al., 2000). Consequently, their analysis is considered important in this research.

Thus, it is supposed that the older the organisational staff, the greater experience and greater concern for the reputation of the company in which they work, since reputation determines the survival of the firm and their job stability. For this reason, the study hypothesis that arises is:H3 Older employees have a better (higher) perception of reputation.

Gender is an important variable when reputation is being studied. Caruana and Chircop (2000) and Davies et al. (2004) show that men and women have different perceptions of reputation. This can be justified by psychological reasons. At the organisational level, the fact that women suffer the phenomenon of vertical segregation, i.e., even with the same level of education, training and experience, they cannot reach the highest hierarchy levels. This may encourage their views of reputation to be different, so hypothesis proposed is:H4 Male employees have a better (higher) perception of reputation than female employees.

Level of education is another personal variable that, a priori, can influence the employee views of reputation. Higher levels of education are associated with an increased ability to process information and ability to discriminate between varieties of stimuli (Wiersema and Bantel, 1992). Although there is no evidence of the link between the level of education and perceived corporate reputation, skills and abilities to process information derived from a high educational level (Wiersema and Bantel, 1992) imply that the employee who has more knowledge and participation in management, is going to have a greater awareness of the importance of reputation and its proper configuration. Moreover, given that the level of education affects the social orientation of individuals (Kelley et al., 1990; Quazi, 2003), those employees with high educational levels will attach more importance to the configuration of the company's overall reputation.

Another aspect is that companies with senior management teams with a higher level of education are more likely to spend more resources on reputation management, because they recognise the need to manage it properly (Carter, 2006).

However, this does not require employees to have a more or less positive view of their company and, therefore, a greater view of reputation. But the fact that the employees with a higher educational level participate in the management of the company and being more sensitive to reputation management must involve their best perception. For this reason, the proposed hypothesis is:H5 Employees with higher level of education have a better (higher) perception of reputation.

Regarding the last control variable considered in this research, the job position, again no conclusive results have been found about its relationship with the employee views of reputation. Some authors have suggested that while an employee is placed in a position, the company is able to promote higher levels of identification with itself, the company can influence the employee's actions at work (Dutton et al., 1994). In particular, when the identification of an individual with the company is closely linked to his/her own image, he/she is more concerned about the company's reputation (Chatman et al., 1986). Consequently, and as employees identified more with the organisation should be managers and professionals because of their higher indoctrination about it, both groups have the most involvement in reputation management. Moreover, as the reputation management is developed at management levels, because it is an intangible source of competitive advantage, it is understood that the direction of the organisation is the group which is more sensitive and worried about reputation and has a better feeling about it, trying to redirect it when it does not have the sought value.

Hence, we understand that the higher management position holds, the higher view of reputation the employee will have. Based on this, we propose the following hypothesis:H6 Employees with higher job position have a better (higher) perception of reputation.

The control variables may also have significant relationships with management styles that are developed in the company, so they are analysed in detail. However, it should be noted that we are talking about two different groups. On the one hand, the control variables are derived from the employees (characteristic traits of them), while the existence of one or another management style depends on the firm. Despite this, it is believed that there is a significant correlation between how an employee views the management style and their age, gender, level of education and job position.

In relation to age, it may be expected that younger employees prefer a participative management style because they seek to acquire and share knowledge and experiences of their colleagues and superiors, to develop initiatives and to solve problems in consensus, being creative. By contrast, the older employees have already acquired such experience, so they prefer a competitive management style, in which targets and goals are set, seeking efficiency, which allow them to achieve promotions and improve their professional status and job position. Based on this, the two hypotheses are posed:H7 Younger employees are more identified with a participatory management style. Older employees are more identified with a competitive management style.

Gender variable may also influence management styles. Loden (1985) maintains that there are two types of leadership styles: the ‘male’ style, characterised by competitiveness, hierarchical authority, high control of the leader and the analytical resolution of problems; and the ‘female’ style characterised by cooperation, collaboration between the leader and subordinates, low control of the leader and problem-solving based on intuition, empathy and rationality. In this sense, Rosener (1990) states that women managers emphasise the participation, share power and information, and enhance the work of others; while Kaufmann (1996) states that the purpose of male management style is to access to the higher job positions of the organisation. According to this, we can appreciate a relationship between a participative management style with the developed by women, and a competitive management style with the developed by men. On this basis, two hypotheses are proposed:H9 Female employees are more identified with a participative management style. Male employees are more identified with a competitive management style.

In a similar way, the level of education influences the abilities and skills of employees and their preference to follow a management style or another. Specifically, and taking into account that the level of education affects the social orientation of individuals (Kelley et al., 1990; Quazi, 2003), we suppose that those with a high level of education have more knowledge and interpersonal, communication, learning and management skills, so they are able to take part effectively in teams, considering them useful for their professional and organisational development. However, employees with the lack of the necessary knowledge and skills for the position they develop, prefer to set some goals to achieve to their subordinates, and to monitor their implementation. Therefore, it raises the hypotheses:H11 Employees with a high level of education are more identified with a participative management style. Employees with a low level of education are more identified with a competitive management style.

Finally, job position may also influence the preferred management style. Thus, employees in lower hierarchical levels tend to be more specialised, both horizontally and vertically. To improve professionally, they need job enrichment. The existence of a participative management style allows them to grow professionally and benefit from all its virtues.

By contrast, the jobs located in the top of the organisational structure are related to the management, the achievement of goals and the development of strategic planning so they prefer to develop a competitive management style, which requires each one of their subordinates to understand their objectives, responsibilities and associated rewards. Therefore, greater job position, greater interest in developing a competitive management style.

However, as this research is in the field of audit firms, compounded by a vast majority of professionals, the point of the scenarios vary greatly. The work of auditors is developed mostly in teams, involving various professionals (junior auditors, audit assistants, senior auditors, etc.), which favours the establishment of a participative management style.

In contrast to this, those who develop less professional positions related to the management of the audit firm (secretaries, receptionists, etc.), depending on auditors and managers, prefer a competitive management style.

Based on the above, the following hypotheses are posed adapted to the sector:H13 Employees in high job positions are more identified with a participative management style. Employees in low job positions are more identified with a competitive management style.

This research focuses on the service sector, especially in accounting audit firms. Recent financial scandals have created a social perception that auditors are professionals who have been acting with too much freedom; ceasing to be guarantors of financial information to become advocates for the interests of the companies they audit (García Benau and Vico Martínez, 2003). Thus, people have ceased to believe that they work for the public interest and their reports and authorities that control them have lost the confidence of users. For that reason, people think that more regulation is required to ensure its independence.

This situation justifies the need to study the perception of the reputation of the SME audit sector, especially among their employees, as they are actively involved in its configuration and transmission through direct contact with customers, suppliers and society in general. Their contributions are valuable because they are witnesses of legislative changes and work processes generated lately.

However, the sector has traditionally suffered other problems such as a saturated market, the price war or the prominence of the Big Four, because of its high market share globally and nationally. These international Big Four audit firms has: (a) a significant size; (b) a professional conduct defined by the technical competence and the organisation, due to higher investments in human capital, better remuneration of its auditors and the increased time spent conducting audits (Moizer, 1997); and (c) the reflection of a successful image that emerges from combining their own fame and the maintenance of their celebrity clients (García Benau et al., 1999), providing a differentiated product in the audit market (Moizer, 1997). Consequently, these four large firms have better external projection of the image of its auditors (success, celebrity clients and modernity) that gives them a reputation differential with respect to SMEs, which may explain their prevalence in the general international market, the premium they receive for their services (between 16% and 37% depending on the country), and the more confidence in their financial reports (Moizer, 1997).

In this situation, SMEs audit firms do not have a recognised name and their services are considered as generic and with a lower perceived quality than provided by the Big Four (Moizer, 1997), clearly affecting their reputation level.

Therefore, the population of this research are Spanish SMEs accounting audit firms, because they have a greater homogeneity in their level of reputation, target market, management and turnover. In addition, this group is compounded by a large number of companies, which allows developing quantitative and empirical researches. So, we have included those who have more than two employees because the management style of their superiors is more noticeable. A group of 535 companies was obtained from the SABI database (Iberian Balance Analysis System).

Data collection and sampleData collection was developed by mailing questionnaires to the selected Spanish audits throughout 2010. After several contacts by various means (phone and e-mail), 106 firms participated in the research, obtaining 148 questionnaires from employees. The response rate is around 27.66%, representing 19.81% of the business population.

An initial descriptive analysis of the data allowed us to observe that the average age of respondents was 32.5 years old, so that 75% of the sample were 35 years or under, with 63.9% being women. The respondents stayed at their respective companies for an average of 6 years, and their level of education was predominantly university degree (76.8%), and among them 29.6% had a master. As for the job position, 13.4% were top managers, 14.1% were team leaders, 12% were audit assistants, and 15.5% administrative assistants. The first two groups basically develop management functions and the last two operational functions.

MeasuresDependent variable: employee views of corporate reputation in Spanish audit firmsItems relating to the assessment of the employee views of corporate reputation of their organisation have been extracted from Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León (2011), as shown in Table 2. In addition, we performed a pre-test with the collaboration of five practicing auditors and five university professors of accounting and finance area that allowed us to adapt the scale for measuring the employee views of reputation to the specific characteristics of the Spanish audit sector.

Dimensions, attributes and items to be valued by employees.

| Dimensions | Attributes | Items used to measure its attribute |

| I. Management quality and managerial ability | 1. Reputation of managers | - Managers are recognised for their good work by external stakeholders- Managers are recognised for their good work by internal stakeholders |

| 2. Smooth running of the company | - Company uses available resources properly- Company manages its assets properly- Company communicates the goals to the people who has to achieve them- Company evaluates set goals in relation with set objectives | |

| II. Business leadership | 3. Leadership position in the market | - Company is a leader in its activity |

| 4. Admiration and respect that the company raises | - Company is respected by the rest of the companies in its sector | |

| 5. Degree of credibility of the company | - Company has a high degree of credibility | |

| III. Human resources | 6. Ability to attract and develop talented staff | - Staff with the specific knowledge and abilities required are attracted |

| 7. Ability to retain talented staff | - Key employees for the company are kept | |

| 8. Employee satisfaction with the company | - Employees are satisfied with their company | |

| IV. Ethics, culture and corporate social responsibility | 9. Ethical commitment of top management | - Managers have an ethical commitment in the development of their activity- Codes of conduct are used to encourage ethical behaviour of employees |

| 10. Existence of values and beliefs shared by members of the company | - Cultural values and beliefs are shared by the members of the company | |

| 11. Environmental protection | - Company develops activities to protect the environment | |

| 12. Information transparency in the activities of the company | - Company considers as important information transparency in its activities | |

| V. Products and/or services | 13. Retention of customers: loyalty | - Company maintains long-term relationships with customers |

| VI. Innovation | 14. Innovativeness | - Your company has made an effort to reinvent the way it does business- Your company is a pioneer in introducing new services- Your company is a pioneer in introducing new processes to deliver services- Your company is a pioneer in introducing new technologies |

| 15. Development of new products and services | - Your company has increased the number of new services introduced in the last three years | |

The variable management style was measured by four items that represent the four management styles discussed above: participative (your manager promotes teamwork, consensus and participation among employees), innovative (your manager promotes individual initiative, risk taking and innovation), conservative (your manager promotes safety in employment, job tenure and the existence of low uncertainty), and competitive (your manager promotes aggressive competitiveness and the achievement of ambitious goals). These items were adapted from Cameron and Quinn (1999).

All items related to employee views of corporate reputation and management style are rated using a 7-point Likert scale, where 1 is a total disagreement with the item and 7 represents a total agreement. Its reliability and validity are guaranteed because they do not present significant differences in their results compared with metric scales (Dolnicar and Grün, 2007).

Control variablesIn our analysis, the variable age of employees has been measured by the number of years since their birth. Gender is a dichotomous variable (male or female), which implies that a negative relationship with another variable is related to the men perspective, while a positive relationship is related to women perspective. Level of education is measured considering the different Spanish levels of education (secondary, intermediate vocational training, higher vocational training, university degree, and master). Finally, job position has been encoded in audit-related positions and not audit-related positions, where the first involving a higher job position. This transformation was done to avoid dispersion problems of the data, given the wide range of job positions that can be found in the audit firms.

ProcedureAfter data collection, we examined the reliability of the items included in the measurement tool of the employee views of corporate reputation to verify it with internal consistency.

To examine the validity of the tool, we examined the content and construct validity. Content validity is ensured by having followed all the methodological and technical criteria established in the literature. Construct validity is checked by: (a) the convergent validity, which requires an exploratory factor analysis of principal components to group the used items in factors and to examine the structure of their interrelations with the definition of common underlying dimensions; (b) discriminant validity, which assesses the degree in which there are two different items which should measure different concepts, for which the correlations between constructs are calculated; and (c) the nomological validity, which checks that the measuring tool behaves as expected with respect to other theoretically related constructs. The analysis of correlations and theoretical relations verify the validity of the construct.

In any case, the validity of the proposal is confirmed by the estimation of a structural equation model following the method of Anderson and Gerbin (1988). So, first the quality of the measurement of the constructs is analysed, through a confirmatory factor analysis, and then the structural model used to determine the employee views of corporate reputation is estimated.

Finally, to test the proposed hypotheses a path analysis is developed, studying the interrelation between management styles and employee views of reputation as well as the influence of the control variables.

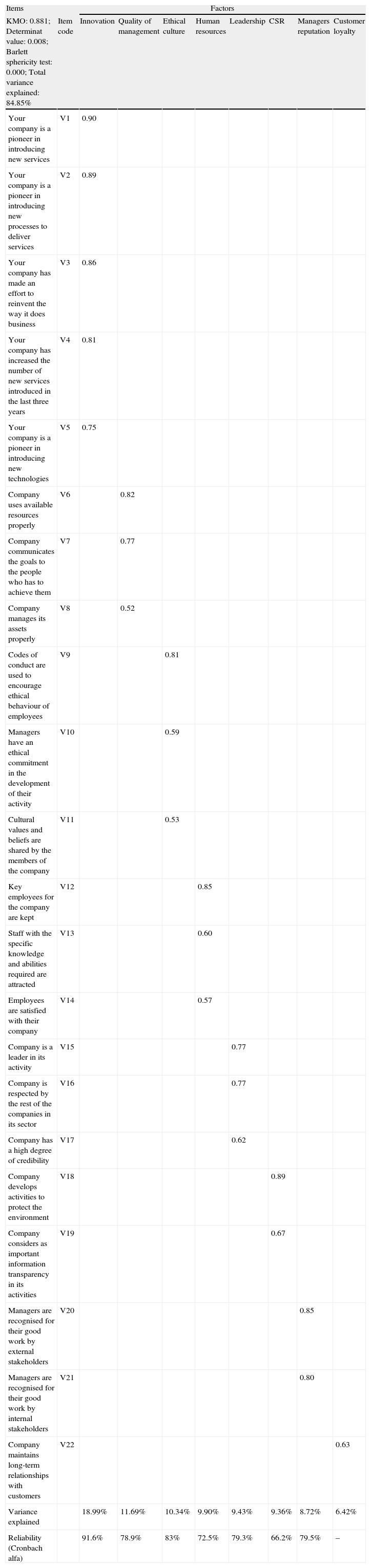

ResultsQuality of the employee views of corporate reputation measureThe reliability was analysed using Cronbach alpha, which reached a value of 92.9%, being an excellent indicator of internal consistency. Convergent validity was verified by an exploratory factor analysis of principal components which confirmed the creation of similar factors that the obtained by Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León (2011). Table 3 shows the eight factors obtained: (1) Innovation, which includes all items proposed; (2) Quality of management, which includes the proper use of resources, communication of goals and the development of skills; (3) Ethics and corporate culture, since it focuses on issues concerning codes of conduct, ethical commitment and shared values and beliefs; (4) Human resources, consisting of three items on employee attraction and retention and the level of satisfaction of them; (5) Leadership, in terms of respect, credibility and becoming an industry leader; (6) Corporate social responsibility, which includes information transparency and environmental protection; (7) Reputation of management staff, about the recognition of their good management; and (8) Customer loyalty with a single item related to it. Therefore, created factors have important similarities with the theoretical model proposed by Olmedo Cifuentes and Martínez León (2011).

Exploratory factor analysis of the employee views of reputation: rotated component matrix.

| Items | Factors | ||||||||

| KMO: 0.881; Determinat value: 0.008; Barlett sphericity test: 0.000; Total variance explained: 84.85% | Item code | Innovation | Quality of management | Ethical culture | Human resources | Leadership | CSR | Managers reputation | Customer loyalty |

| Your company is a pioneer in introducing new services | V1 | 0.90 | |||||||

| Your company is a pioneer in introducing new processes to deliver services | V2 | 0.89 | |||||||

| Your company has made an effort to reinvent the way it does business | V3 | 0.86 | |||||||

| Your company has increased the number of new services introduced in the last three years | V4 | 0.81 | |||||||

| Your company is a pioneer in introducing new technologies | V5 | 0.75 | |||||||

| Company uses available resources properly | V6 | 0.82 | |||||||

| Company communicates the goals to the people who has to achieve them | V7 | 0.77 | |||||||

| Company manages its assets properly | V8 | 0.52 | |||||||

| Codes of conduct are used to encourage ethical behaviour of employees | V9 | 0.81 | |||||||

| Managers have an ethical commitment in the development of their activity | V10 | 0.59 | |||||||

| Cultural values and beliefs are shared by the members of the company | V11 | 0.53 | |||||||

| Key employees for the company are kept | V12 | 0.85 | |||||||

| Staff with the specific knowledge and abilities required are attracted | V13 | 0.60 | |||||||

| Employees are satisfied with their company | V14 | 0.57 | |||||||

| Company is a leader in its activity | V15 | 0.77 | |||||||

| Company is respected by the rest of the companies in its sector | V16 | 0.77 | |||||||

| Company has a high degree of credibility | V17 | 0.62 | |||||||

| Company develops activities to protect the environment | V18 | 0.89 | |||||||

| Company considers as important information transparency in its activities | V19 | 0.67 | |||||||

| Managers are recognised for their good work by external stakeholders | V20 | 0.85 | |||||||

| Managers are recognised for their good work by internal stakeholders | V21 | 0.80 | |||||||

| Company maintains long-term relationships with customers | V22 | 0.63 | |||||||

| Variance explained | 18.99% | 11.69% | 10.34% | 9.90% | 9.43% | 9.36% | 8.72% | 6.42% | |

| Reliability (Cronbach alfa) | 91.6% | 78.9% | 83% | 72.5% | 79.3% | 66.2% | 79.5% | – | |

Furthermore, when the correlations between the items that compound each factor are analysed, and they are high and significant, then convergent validity is ensured.

The reliability of all the factors formed reaches 84.6%, and each of the factors is greater than 65%, as shown at the bottom of Table 3, so that the internal consistency of each factor and the construct used is high and acceptable.

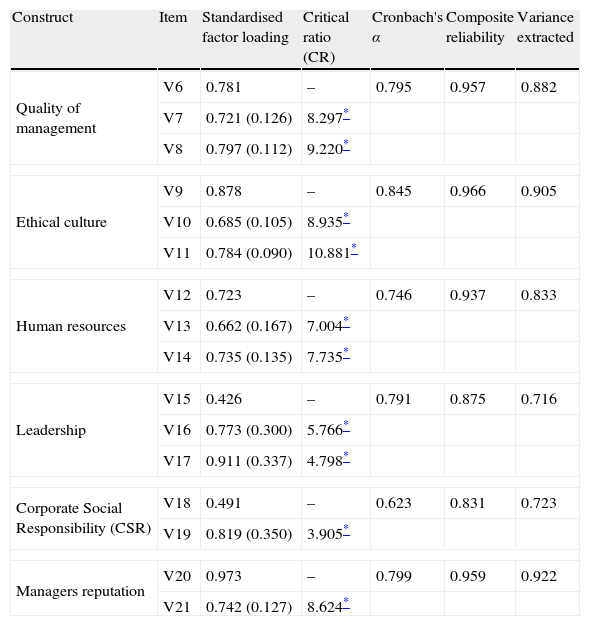

After this initial exploratory stage, we performed a confirmatory factor analysis on the results of principal component analysis. In the first estimation, we observe that the fit indices are not satisfactory, so the model is not acceptable. Thus, the model was adjusted eliminating the factors related to innovation and customer loyalty, as shown in Table 4. All fit indices exceed the threshold 0.9, indicating an acceptable fit of the model (Table 4). The mean square error is also low (RMSEA=0.059).

Confirmatory factor analysis results.

| Construct | Item | Standardised factor loading | Critical ratio (CR) | Cronbach's α | Composite reliability | Variance extracted |

| Quality of management | V6 | 0.781 | – | 0.795 | 0.957 | 0.882 |

| V7 | 0.721 (0.126) | 8.297* | ||||

| V8 | 0.797 (0.112) | 9.220* | ||||

| Ethical culture | V9 | 0.878 | – | 0.845 | 0.966 | 0.905 |

| V10 | 0.685 (0.105) | 8.935* | ||||

| V11 | 0.784 (0.090) | 10.881* | ||||

| Human resources | V12 | 0.723 | – | 0.746 | 0.937 | 0.833 |

| V13 | 0.662 (0.167) | 7.004* | ||||

| V14 | 0.735 (0.135) | 7.735* | ||||

| Leadership | V15 | 0.426 | – | 0.791 | 0.875 | 0.716 |

| V16 | 0.773 (0.300) | 5.766* | ||||

| V17 | 0.911 (0.337) | 4.798* | ||||

| Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) | V18 | 0.491 | – | 0.623 | 0.831 | 0.723 |

| V19 | 0.819 (0.350) | 3.905* | ||||

| Managers reputation | V20 | 0.973 | – | 0.799 | 0.959 | 0.922 |

| V21 | 0.742 (0.127) | 8.624* | ||||

Chi-squared Satorra-Bentler: 131.5; degrees of freedom: 90; CFI: 0.963; IFI: 0.964; NFI: 0.903; RMSEA: 0.059.

The results in Table 4 lets us confirm the reliability of the scale, since both Cronbach alpha and composite reliability are above the recommended value of 0.7 for all constructs. In addition, the explained variances are above 70%, and the standardised factor loadings are significant for all items. These results confirm the convergent validity of the employee views of corporate reputation model.

To check the discriminant validity correlations were calculated between constructs (Table 5). Since all factors are away from the unit, discriminant validity is confirmed.

Means, standard deviations and correlations between constructs.

| Construct | Mean | Std. deviation | Correlations | |||||

| F1 | F2 | F3 | F4 | F5 | F6 | |||

| F1. Quality of management | 5.393 | 0.899 | 1.000 | 0.592 | 0.591 | 0.521 | 0.488 | 0.436 |

| F2. Ethical culture | 5.222 | 1.041 | 1.000 | 0.584 | 0.404 | 0.410 | 0.529 | |

| F3. Human resources | 5.430 | 0.958 | 1.000 | 0.547 | 0.392 | 0.467 | ||

| F4. Leadership | 5.007 | 1.062 | 1.000 | 0.371 | 0.359 | |||

| F5. CSR | 4.926 | 1.157 | 1.000 | 0.306 | ||||

| F6. Managers reputation | 5.763 | 0.964 | 1.000 | |||||

To test the proposed hypotheses, we developed a path analysis as shown in Fig. 2.

To do this, we used the software package AMOS 18 following the method of maximum likelihood. To simplify and test the hypotheses, a joint variable of employee views of corporate reputation is used to relate to management styles. In particular, a construct with the weighted combination of the 6 obtained factors (dimensions) from the confirmatory factor analysis made previously is done.

Thus, the results of the proposed model are shown in Table 6. Several relationships are significant (p<0.05, two-tailed test), as well as the model fitting well according to the indicators shown in the bottom of Table 6.

Path analysis results.

| Regression | Std. factor loading | Std. error | CR | p* | Hypotheses | ||

| Participative style | → | EVCR | 0.396 | 0.106 | 5.215 | 0.000 | H1 (+) |

| Competitive style | → | EVCR | 0.238 | 0.083 | 3.262 | 0.001 | H2 (+) |

| Age | → | EVCR | −0.017 | 0.065 | −0.223 | 0.824 | H3 (+) |

| Age | → | Participative style | 0.110 | 0.051 | 1.325 | 0.185 | H7 (−) |

| Age | → | Competitive style | 0.006 | 0.066 | 0.067 | 0.947 | H8 (+) |

| Gender | → | EVCR | −0.094 | 0.126 | −1.190 | 0.234 | H4 (−) |

| Gender | → | Participative style | 0.016 | 0.098 | 0.189 | 0.850 | H9 (+) |

| Gender | → | Competitive style | −0.189 | 0.125 | −2.117 | 0.034 | H10 (−) |

| Level of education | → | EVCR | −0.071 | 0.066 | −0.829 | 0.407 | H5 (+) |

| Level of education | → | Participative style | 0.241 | 0.051 | 2.633 | 0.008 | H11 (+) |

| Level of education | → | Competitive style | 0.027 | 0.065 | 0.281 | 0.779 | H12 (−) |

| Job position | → | EVCR | 0.128 | 0.123 | 1.594 | 0.111 | H6 (+) |

| Job position | → | Participative style | 0.189 | 0.096 | 2.173 | 0.030 | H13 (+) |

| Job position | → | Competitive style | −0.015 | 0.122 | −0.161 | 0.872 | H14 (−) |

| Model fit | χ2 | Degrees of freedom | GFI | CFI | AGCI | IFI | NFI | RMSEA | Hoelter 0.01 |

| 2.091 | 2 | 0.996 | 0.999 | 0.942 | 0.999 | 0.983 | 0.018 | 630 |

EVCR: Employee Views of Corporate Reputation.

Both participative and competitive management style show a positive effect on the employee views of corporate reputation, indicating that both styles are precursors of reputation. Hypotheses 1 and 2 are accepted.

Second, not all established relationships with the control variables are significant. The only hypotheses accepted are: (a) H10, implying that male employees are more identified with a competitive management style; (b) H11, which explains why employees with a high level of education are identified with a participative management style; and (c) H13, where employees that are engaged in activities related to audit and, therefore, with a higher job position, show a greater preference for a participative management style.

When an individual analysis of each control variable (excluding the rest in the path analysis) is developed, the same results are obtained. Age does not moderate the model because it does not affect the principal relationship between management styles and reputation, being not significant. In the case of gender and level of education, they are partial moderators of the principal relationship because they only significantly affect one variable in the model. However, the individual results of the gender show that it has an indirect effect on the reputation, which indicates that the perception of the reputation from men and women may differ slightly. Regarding level of education, it only varies slightly in principal relationships between participative management style and reputation, without having any indirect effect on the rest of variables. Finally, job position moderates the model that links participative management style and the competitive with employee views of corporate reputation because it significantly affects the factor loading of the rest of the variables. In addition, when job position is studied as the only control variable included in the model, it also has the same indirect effect on the reputation that gender, being significant its relationship with reputation (which is referred to in H6).

To complete the results obtained, the correlations between the four control variables are analysed in detail. Several findings are obtained and its implications are shown in Table 7.

Conclusions from the correlations among variables control.

| Significant correlations | Sense of the correlation | Conclusions |

| Age – job position | Negative (−0.254)The younger the employee, the better job position. | This is because audit firms have audit assistants, junior auditors, etc., who are usually young graduates that have finished masters and passed the examinations to be to be entitled to exercise as auditor. However, SME audits find the problem that many of these young auditors prefer to work in firms of high reputation (BIG 4), because small firms and their services are recognised as generic and lower perceived quality (Moizer, 1997). Others, however, prefer to create their own audit firm. This is why that business suffers a high turnover of auditors, which is especially evident in the sample of this research (SMEs). |

| Age – level of education | Negative (−0.241)The younger the employee, the higher educational level. | This result shows consistency with the previous one because new generations are usually more prepared. In addition, for more than two decades a higher level of education to be entitled to exercise as auditor is required. |

| Gender – job position | Negative (−0.204)Male employees have more job positions related to audit work. | This is because the audit profession has been performed mainly by men for many years, which corroborates the horizontal segregation that exists in the industry. In addition, the audit sector is very masculine, since the signing of a report from a man appears to offer greater reliability to its customers and users (financial community) than the report that is signed by a woman. |

| Gender – level of education | Negative (−0.373)Male employees have a higher level of education. | This result shows consistency with the previous one because it seems that job positions not related to audit work and consequently require less level of education (receptionists, secretaries, etc.) are performed mainly by women. By contrast, their male partners played more professional job positions, requiring higher levels of education. |

| Level of education – job position | Positive (0.379)The higher educational level, the more possibilities to have a job position related to audit work. | To be an auditor or develop activities directly related to audit requires a high level of education, which is not required for other job positions developed in the office, not directly linked to the audit service. |

Horizontal occupational segregation means that women work in a small number of professions, considered feminine, related to caregiving, teaching or services. This reality comes from the process of wage-earning and commercialisation of labour; that is, as the productive and service activities have been passed from the domestic sphere to the organisations (business or public institutions), women have been filling force working, but in activities or sectors that they have already occupied (Ibáñez Pascual, 2008).

The aim of this paper has been to cover four gaps found in corporate reputation literature. The first involves the empirical application of a tool for measuring the employee views of corporate reputation, given their importance in shaping the company's corporate reputation (Helm, 2007, 2011).

The second gap has been to adapt this tool to the SME audit firms from an organisational perspective; since, in general, the tools used in academic and prestigious institutions (Fortune, Financial Times, Reputation Institute, Merco) are focused on large companies. Also, the researches on SMEs in the field of audit firms have used a financial perspective, equating reputation and image (whose differentiation has been described) to estimate the quality of services from a customer perception, comparing large audit firms with the rest and ignoring its internal stakeholders (García Benau et al., 1999; Moizer et al., 2004; Cameran et al., 2010a,b). This research emphasises in audits because they are labour intensive firms which make the overall reputation of the organisation depends heavily on employee-customer interaction (Davies et al., 2004, 2010; Helm, 2011). Thus, the proposed tool for measuring the employee views of corporate reputation of Spanish accounting audit firms from an organisational perspective consists of six dimensions: Smooth running of the business, Ethics and corporate culture, Human resources, Leadership, Corporate Social Responsibility and Reputation of manager.

The third gap that we have attempted to cover is to improve the management of this intangible asset in service organisations (audits). To get this, and taking into account the identity of the firm, we have demonstrated the importance of the management style developed by managers in the employee views of reputation, and what kind of management style can have more influence on the reputation has been explored. Thus, we have obtained empirical evidence that both participative and competitive management style have a positive and significant influence on employee views of reputation in Spanish SME audit firms. That both styles being significant shows that Spanish audits use them interchangeably and, even, in a complementary way. A consolidated participative management style promotes collaboration and the employee commitment and involvement in decision-making and organisational performance, while competitive management style seeks to achieve a number of objectives through an aggressive competitiveness among employees. Therefore, it seems that a management style does not have to be better than another, since each one is adapted to the identity and cultural circumstances introduced by each manager in the organisational unit and company. As a main conclusion we state that the existence of a distinctive management style assumed by employees (participative or competitive) will generate a better perception of the reputation of the Spanish SME audits.

Finally, the fourth gap covered in this research is derived from the introduction of control variables, which allowed us to study their effect on the reputation and management styles perceived by employees. Three basic conclusions have been reached in Spanish audit sector: (a) male employees prefer a competitive management style, as established by Loden (1985) about the male leadership style; and (b) a high level of education and job position has an impact on a preference for participative management style in the studied industry.

From the analysis of the correlations among the control variables a doubt may arise. If male employees prefer competitive management style (according to the hypothesis H10) and they are also those with a higher level of education (gender and educational level correlation), then how is possible that a higher level of education affects the preference of a participative management style (hypothesis H11)? In general, employees with higher levels of education are involved in audit activities (correlation between level of education and job position), and teamwork is essential in audits to the development of all the auditing activity. In general, men prefer a competitive management style, but the kind of audit work gives priority to teamwork so men auditors with a higher level of education have to opt for a participative management style that facilitates the development of their work.

The results of this research can help managers of Spanish accounting audit firms to improve the management of reputation. The management style that managers develop influences directly and positively the employee views of reputation, especially in the case of participative or competitive style. Moreover, this perception will be transferred to other stakeholders with which the audit interacts, such as customers, users of information, financial community and society in general. It justifies the great role that employees have in shaping the reputation of the firm and its external assessment.

Some aspects may be taken into account to manage the employee views of reputation. If the workforce is mostly male, they are going to be more identified with a competitive management style. However, the type of work can be decisive in order to facilitate the development of certain tasks, e.g. collaborative ones require a more participative management style. Other aspect is the level of education; employees with a higher educational level are more identified with a participative management style. This is something to consider when the organisational staff has to be managed, especially those professionals with higher added value, which just tend to have more training. Moreover, as a result of the above, the staff of higher job positions is also identified with the participative style.

It is also important to note that the participative style contributes more to better employee views of reputation than the competitive (see the standardised coefficients in Table 6). For this reason, the participative management style is recommended to the audit firms among employees with higher level of education and job position.

Despite this recommendation, excluding the competitive management style is difficult and even dangerous in audits. It can be managed properly to get the better reputation perspective of the firm and it also can be an incentive to try to achieve and exceed goals.

However, the present research has some limitations. One of them is that there is no single management style in business reality, whose characteristics coincide fully with the established typologies and the traits of different styles which are intermingled. When the management styles have been defined, we have appreciated that participative and competitive styles did not correlate, and the rest have to be excluded for their shared and simultaneous development.