After a steady growth in global offshoring activities, it appears now a marked flow in the opposite direction with both a partial and full reversal of offshoring decisions. Research on reshoring put less stresses on the operation of dispersed facilities of an intra-firm network manufacturing. The purpose of this paper is to address the relevance of strategic capabilities for the operation of international manufacturing to the reshoring decision. The paper reports on retrospective studies of three European based companies, which have had recent reshoring experience. We adopt qualitative research using a case-based methodology that includes multiple in-depth interviews based on three companies. The study demonstrates that managerial challenges in the operation of dispersed facilities have played an important role in the reshoring decision. The findings allow understanding how the capability dimensions, ‘thriftiness’ and ‘learning’ being the most important, connect with the phenomenon of reshoring.

Manufacturing in offshore facilities has been apparent since the 1980s and has become one of the most important changes made by multinational companies (Hernández and Pedersen, 2017; Jacob and Strube, 2008). In spite of the fact that this tendency is still ongoing, over the past 10 years there has been a noticeable movement in the opposite direction; this includes both a partial and full reversal of previous offshoring decisions. This phenomenon has been termed reshoring (Ellram et al., 2013), or backshoring (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen, 2014).

The reshoring phenomenon has attracted the attention of both the media and academia, as it is an indication of a change from an established trend in global manufacturing configurations. In their literature review on manufacturing backshoring, Stentoft et al. (2016) indicated that out of 20 papers selected between 2009 and 2016, 14 had been published from 2014 and later, which is a strong indication of a growing interest by researchers in this topic. Other authors acknowledge the rise of interest on this phenomenon, since the majority of articles were published within the past three years – between 2015 and 2017 (e.g. Barbieri et al., 2018; Wiesmann et al., 2017). This view is supported by Tate et al. (2014) who write that a significant portion of US companies (40% of 319 companies) are actively involved in reshoring. The CBI European survey in 2014 found that one-third of the surveyed firms had moved production back to their home market in the last three years (Wilkinson et al., 2015). Dachs and Kinkel (2013) also report a similar ratio of backshoring in offshoring firms, based on 3300 companies from the European Manufacturing Survey (EMS).

With the rapidly increasing amount of publications on this topic, an array of motivations have been identified by scholars (e.g. Foerstl et al., 2016; Fratocchi et al., 2016; Stentoft et al., 2016). In this, the most reported are related to a decrease in cost-savings, indicating that reshoring is either governed by a cost increase witnessed in the host location (Tate et al., 2014) or a failure to realise the cost benefits from offshoring (Kinkel and Maloca, 2009). Despite literature has focused on the failure to realise the cost benefits, there are other drivers less investigated by extant literature. For instance, a lack of expected quality (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen, 2014; Fratocchi et al., 2014; Martínez-Mora and Merino, 2014), proximity to R&D (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen, 2014; Kinkel and Maloca, 2009; Tate et al., 2014), and difficulties due to the physical and psychic distance (Gray et al., 2013; Kinkel, 2014a, 2014b; Tate et al., 2014), etc.

Unfortunately, in today’s international manufacturing, there is a number of companies that they make relocation decision rather influenced by the competitiveness of offshore manufacturing operations. Scholars have argued that reshoring may follow from the inability of firms to manage complex challenges created by offshore production (Manning, 2014). Moreover, it has been suggested that there is a need to understand whether or not reshoring decisions are driven by difficulties in disseminating relevant knowledge and the long-term adaptations of manufacturing operations in dispersed facilities (Ellram et al., 2013; Gray et al., 2013), and the role of learning in reshoring and insourcing (Bals et al., 2016). All of these reasons belong to the operation of a single firms’ dispersed facilities. To the best of our knowledge, the operational issues that influence the phenomenon of reshoring have not been investigated so far. In particular, there is a need to evaluate the reshoring decisions from a ‘how’ perspective.

Meanwhile, to address the above mention drivers going beyond cost factors, issues captured by the management of activities in international manufacturing networks could help understand how reshoring actually follows from a ‘failure’. Shi and Gregory (1998) identified a list of capabilities of international manufacturing networks, derived from the configuration and coordination of the network. This included targets accessibility, thriftiness ability, learning and mobility. Centres on Shi and Gregory's (1998) research, studies suggest that by effectively managing the flows of goods and knowledge in the network of dispersed facilities, the strategic capabilities for international manufacturing may be realised (Colotla et al., 2003; Miltenburg, 2009). Thus, extending the existing literature, we argue for the value of looking at the phenomenon of reshoring from the strategic capabilities of intra-firm network operation viewpoint. Specifically, this study concerned with, how the dimensions of network-manufacturing capability infer the phenomenon of reshoring.

Since case study research has the potential to disclose better an understanding of how the activities performed in the decentralised environment (Ellram et al., 2013), we select case-study methodology with multiple cases. Our work centres on the analysis of in-depth case studies of three companies – two Spanish origin and one Swedish origin – from different industry sectors. Studied companies have recently reshored some or all of their manufacturing activities from disperse locations.

By applying the network manufacturing capability perspectives to the reshoring context, this study advances our knowledge of global manufacturing. In particular, our study views manufacturing reshoring from the perspective of operation or management of activities in dispersed facilities, that explains the relationship between drivers and reshoring phenomenon via individual dimension of capabilities. Hence, the findings have implications both for reshoring research and research on capability development in international operations. Moreover, present research uncovers valuable insight from failure-in-offshoring cases that, we believe, will help practitioners to address the challenges of reshoring more effectively.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. The second section presents the background literature concerning reshoring and provides a theoretical background to frame the study from network manufacturing perspective. The third section is concerned with the methodology used for this study. The within-case analysis is reported in the section ``Within-case analysis’’, and the fifth section discusses the cross-case analysis and findings of the study. We conclude by outlining contributions, pointing out the limitations of this study, and suggesting future research directions.

Research backgroundManufacturing reshoringThe phenomenon of transferring the manufacturing facility from host locations has been addressed by several authors, using the terms reshoring or backshoring: “re-concentration of parts of production from own foreign locations as well as from foreign suppliers to the domestic production site of the company” which is totally owned by the home company (Kinkel and Maloca, 2009; p. 155). According to Ellram et al. (2013), reshoring can be defined as moving manufacturing back to the country of its parent company. Alternatively, “moving production in the opposite direction of offshoring and outsourcing is termed as backshoring or insourcing” (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen, 2014; p. 60). In defining partial reshoring, Baraldi et al. (2018) added the concept ‘selective reshoring’, i.e., in addition to whole manufacturing operations the relocation also concerns specific individual activities, even very particular activities. Further, reshoring is fundamentally concerned with where manufacturing activities are to be performed, independent of who is performing the manufacturing activities in question. Therefore it is a location decision only, as opposed to a decision regarding location and ownership (Gray et al., 2013). In this paper, we follow Fratocchi et al. (2014) and Tate et al. (2014) in viewing the phenomenon, as a reverse decision of a previous offshoring process which might be whole or part of a facility.

We have conducted an extensive literature search based on a collection of papers published from 2000 to 2018. Using various sources (e.g. Web of Science, Science Direct), with a predetermined set of keywords (e.g. “reshoring”, “backshoring”, “manufacturing relocation”, “global manufacturing”), a selection of 55 potentially relevant papers were chosen. Through the snowballing approach, this set was extended to a total of 78 publications. These selected articles were then categorised into two streams; articles that are concerned with relocation, that is, reshoring (33), and articles that deal with offshoring, local manufacturing, outsourcing, and make-or-buy decisions (45). Further investigation of the second category led to the inclusion of eight additional articles to the first set, and these 41 sources were used to gain knowledge of the recent works on reshoring. In previous studies, some authors have mainly been interested to focus exclusively on reshoring motivations (e.g., Bals et al., 2016; Barbieri et al., 2018; Foerstl et al., 2016; Fratocchi et al., 2016; Stentoft et al., 2016; Wiesmann et al., 2017). Together, these studies reported a vast array of motivations for reshoring. Numerous studies have attempted to categorise those drivers or motivators (for example, Barbieri et al., 2018; Wiesmann et al., 2017).

Specific attention has been given to the motivations for reshoring to the ends: reduction in cost advantages and/or differentials between the home and host locations, and looking beyond the cost perspectives. Adopting cost-based drivers of reshoring, scholars (e.g., Di Mauro et al., 2018; Ellram et al., 2013; Foerstl et al., 2016; Fratocchi et al., 2014; Kinkel and Maloca, 2009; Kinkel, 2012; Wiesmann et al., 2017) have identified the main reasons, such as increased labour cost, increased logistics cost, shrinking market size, government incentive and exchange rate fluctuation, among others. On the other hand, the phenomenon of reshoring has been viewed focusing on how to obtain unique sets of resources and competences able to give a sustainable competitive advantage to the company, i.e., resource-based driver for reshoring (Grappi et al., 2018). In this end, company’s decision to reshoring mirror the efforts in developing and/or ensuring critical assets by moving activities back to the home location. For instance, to ensure expected production quality (Ancarani et al., 2015; Canham and Hamilton, 2013), to ensure higher level of flexibility and volatility (Wu and Zhang, 2014), a wish to have production close to R&D, a focus on core activities, and automation (Arlbjørn and Mikkelsen, 2014; Fratocchi et al., 2016; Tate, 2014), to get access to materials, infrastructure and/or suppliers (Ellram et al., 2013).

It is worth noting that, above mentioned latter group of drivers are not directly affected by the cost differentials between the home and host locations, rather influenced by the competitiveness of performing manufacturing activities in dispersed facilities. Despite this group of factors play a significant role, studies neglect the explanations based on causal empiricism of these factors that may help to further our understanding (Delis et al., 2017; Wiesmann et al., 2017). For instance, according to Dachs and Kinkel (2013), the barriers of international manufacturing are not explicitly present in the extant literature. Moreover, Fratocchi et al. (2014) conclude that firm-level factors are at the issue and deserve closer attention. Therefore, in this research we seek to overcome this shortcomings.

A resource-based view perspective on reshoringWhile the theoretical underpinnings of offshoring have been extensively discussed in extant literature, the theoretical foundation of reshoring are more fragmented. In this respect, Fratocchi et al. (2016) and Martínez-Mora and Merino (2014) pointed out that theoretical perspectives based on international business literature (TCE, RBV, OLI) can sufficiently explain the location choices of firms including the reshoring phenomenon. A broader perspective has been adopted by Barney (1991) who argues that strategic resources and capabilities are considered crucial drivers for a company’s location decisions. With respect to the resource-based view (RBV), firm’s resources and capabilities are the foundation of its strategy. Grant (1991) viewed capabilities as ‘organisational routines’, which are made up of coordinated actions to deploy resources. Capabilities involve complex patterns of coordination between people and other resources. Turning to RBV in operations management research, Hitt et al. (2016) state that “orchestrating capabilities, including leveraging the collective capabilities, produces not only stronger and synergetic outcomes but does so in a way to produce ambiguity of cause and effect. This ambiguity makes…. it difficult to imitate” (p. 79).

Effective and efficient use of resources and desired capabilities is a necessary condition for achieving target performance, which in OM terms means that resources must be managed effectively. According to RBV, reshoring strategies could be motivated by the firm’s inability to develop specific resources abroad, and/or to properly exploit the resources in disperse facilities in order to establish competitive advantage (Canham and Hamilton, 2013). Consistent with theoretical approaches such as the RBV, current research delineates the operational decision-making process of a company (involved in international manufacturing) focused, not because of a direct cost problem but, primarily on how to obtain unique set of resources and competences to give competitive advantage.

It is worth noting that, in the context of international manufacturing, activity management generally regard the interactions between the single firm’s home and host facilities, i.e., intra-firm network management. Since, the reshoring process involves decisions as well as changes in the network structure and operation of both the home and host facilities (Baraldi et al., 2018); on its part, manufacturing in dispersed facilities raises the need to pay attention to the network-manufacturing capabilities that generate competences of the firm. A discussion to which we turn in the next subsection.

Network-manufacturing capabilitiesManufacturing strategy is a collective pattern of decisions that acts upon the formulation and deployment of manufacturing resources (Cox and Blackstone, 1998). It aims to align a company’s resources and capabilities to achieve competitive advantage (Slack and Lewis, 2015). In the scope of international manufacturing, the motivation and reasons for going global might be the internal or external pressures of the firms, as described in the ‘eclectic model’ (Dunning, 1980). On the merits of becoming global in manufacturing, a market-based perspective focuses on the aspects that are external to the company, whereas low-cost resource perspectives and issues of size are a focus on the internal aspects of the company (Carr, 1993). From a global production network point of view, manufacturing strategies are in fact an artefact of the reasons that initially determine the globalisation intentions (Größler, 2010). We take manufacturing strategy as the starting point of network configuration, henceforth to derive the network manufacturing capabilities.

Scholars (e.g. Rudberg and Olhager, 2003; Shi and Gregory, 1998) define intra-firm networks as the global manufacturing networks consisting of multiple interconnected facilities owned by the parent company and/or which have direct control over them. Among others, Porter (1986) was the first to posit the distinctive issues of network manufacturing such as, how a firm’s activities are configured worldwide and how the activities are performed. Kogut (1990) distinguishes these activities: initial – which includes access to raw materials, cost and skill differences, and market coverages; and sequential – the coordinated management of the global network. Hence, the decision-making process related to global manufacturing activities involves decisions concerning the configuration of facilities – which primarily addresses structural decisions to design a network, and the coordination – which addresses the operation of activities in globally dispersed facilities (Colotla et al., 2003).

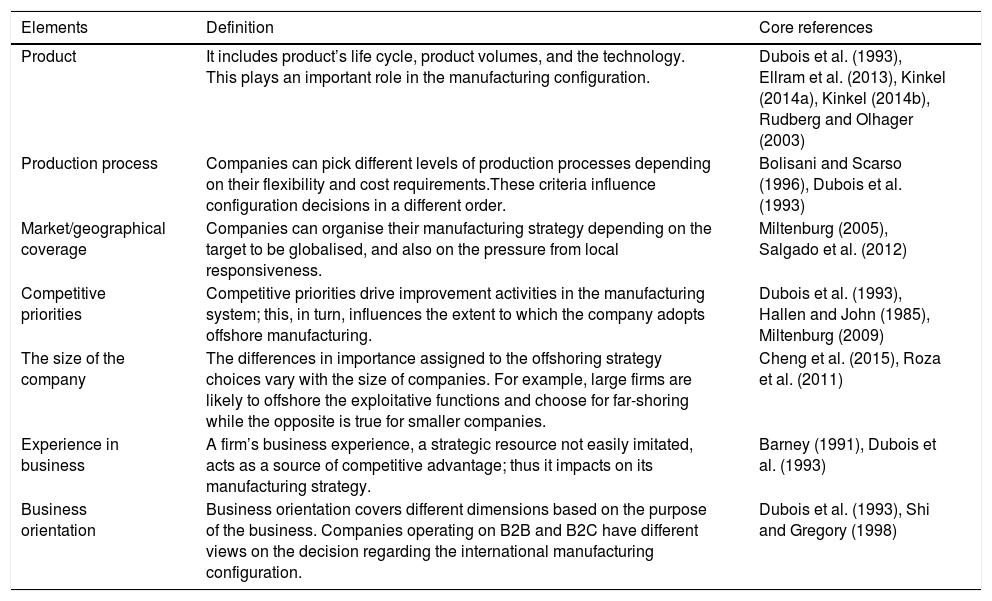

The configuration determines the arrangement of the facilities – i.e. where each activity in the value chain takes place – in the international manufacturing network. This is the first building block of the international manufacturing network (IMN) since the question of where to manufacture and how to serve the customers is answered here. According to Miltenburg (2009), there are many levers for configuration, such as size, focus and the capabilities of the facility, geographic dispersion, and the degree of integration. Meanwhile, configuration decisions are driven by the contextual factors of the market region and the products selected. A comprehensive list of elements linked to the configuration choice is given in Table 1.

Manufacturing strategy elements related to offshore manufacturing.

| Elements | Definition | Core references |

|---|---|---|

| Product | It includes product’s life cycle, product volumes, and the technology. This plays an important role in the manufacturing configuration. | Dubois et al. (1993), Ellram et al. (2013), Kinkel (2014a), Kinkel (2014b), Rudberg and Olhager (2003) |

| Production process | Companies can pick different levels of production processes depending on their flexibility and cost requirements.These criteria influence configuration decisions in a different order. | Bolisani and Scarso (1996), Dubois et al. (1993) |

| Market/geographical coverage | Companies can organise their manufacturing strategy depending on the target to be globalised, and also on the pressure from local responsiveness. | Miltenburg (2005), Salgado et al. (2012) |

| Competitive priorities | Competitive priorities drive improvement activities in the manufacturing system; this, in turn, influences the extent to which the company adopts offshore manufacturing. | Dubois et al. (1993), Hallen and John (1985), Miltenburg (2009) |

| The size of the company | The differences in importance assigned to the offshoring strategy choices vary with the size of companies. For example, large firms are likely to offshore the exploitative functions and choose for far-shoring while the opposite is true for smaller companies. | Cheng et al. (2015), Roza et al. (2011) |

| Experience in business | A firm’s business experience, a strategic resource not easily imitated, acts as a source of competitive advantage; thus it impacts on its manufacturing strategy. | Barney (1991), Dubois et al. (1993) |

| Business orientation | Business orientation covers different dimensions based on the purpose of the business. Companies operating on B2B and B2C have different views on the decision regarding the international manufacturing configuration. | Dubois et al. (1993), Shi and Gregory (1998) |

Next, the coordinated management of network manufacturing defines how the production facilities are interconnected and linked to realising the company’s strategy (Cheng et al., 2015). Coordination involves the alignment and integration of activities in a value chain, which are interdependent but performed by different entities (Martinez and Jarillo, 1991; Srikanth and Puranam, 2011). Designing the activity coordination in dispersed facilities typically includes the decision regarding the degree of centralisation and the exchange of resources across facilities (Hayes et al., 2004). Research on “coordination” (e.g., Martinez and Jarillo, 1989; Reger, 2004) has traditionally distinguished two basic mechanisms, i.e., formal and informal mechanisms of coordination. In this, formal mechanisms involve the centralisation – the level and position of decision authority – and the standardisation of processes and procedures. As such, the activity coordination is mostly supported by a pre-established work procedure which acts as a means of impersonal communication. Next, informal coordination involves activities where two or more entities make substantial contributions of resources as well as know-how toward a previously agreed aim (Bergek and Bruzelius, 2010). More specifically, with an increased interdependence of multiple facilities in a network, informal coordination implies a greater use of personal communication among system-sensitive members, and a mix of impersonal methods of communication (Mascarenhas, 1984).

A manufacturing firm’s competitive position fundamentally depends on the resources and can be adjusted by its capabilities or practices (Teece et al., 1997). Network capabilities and practices emerge as important factors for successfully implementing a manufacturing firm’s production process (Dagnino, 2004). The specific capabilities that result from the dispersion of manufacturing facilities and their integration are called network-manufacturing capabilities (Shi and Gregory, 1998). Therefore, the capabilities necessary to achieve the goals of network-manufacturing are realised through the configuration of manufacturing facilities, and the way manufacturing activities are managed over the network. The advantage gained from the network-manufacturing capabilities through superior resources and/or a superior deployment of resources results in a competitive advantage (Colotla et al., 2003). Eventually, “these capabilities result in a better competitive firm performance” (Jin and Edmunds, 2015; p. 751). Shi and Gregory (1998) proposed a list of strategic capabilities, i.e., target accessibility, thriftiness ability, learning and mobility, of a multi-facility international manufacturing network. In the following paragraphs, we have discussed these four dimensions and identified the characteristics or attributes related to each dimensions of capability.

Target accessibility. Target accessibility comprises the aim of selecting the facility location in a manufacturing network (Cheng et al., 2011). Therefore, the advantages of accessibility are very similar to those of the reasons for dispersion of facilities. Ferdows (1997a) originally identified three classes of location advantages. In addition, other authors have refined and extended those reasons for configuration. Although the list was long, only the three major factors – i.e. access to low-cost production, proximity to market, and access to skills and knowledge – have been empirically validated (Feldmann and Olhager, 2013). Shi and Gregory (1998) highlighted that these are more sensitive to global changes; for example, customer requirements, future trends, information, and competition. Unexpected changes in the external forces might fuel the reconfiguration of global production and related strategies. Hence, an understanding of these driving forces behind the network configuration is essential to the understanding of the missions of international manufacturing.

Thriftiness ability. Economies of scope reflect the ability to develop more efficiency through networking. This ability is mainly obtained from sharing technology, engineering, manufacturing, and development competencies within a manufacturing network for different products (Shi and Gregory, 1998). The benefits of economies of scope are high when competencies, for example, centralised product development, are bundled in a facility and then transferred to other facilities in the network. Hence, the economies of scope ability is fostered by the extent of competencies to perform activities in the dispersed facilities of a network. Economics of scale refers to the advantages gained by the concentration or aggregation of production volume across facilities in a network. If a manufacturing network allows the production of a particular product in multiple facilities, then the bundling of production volume – that is, the degree of concentration – gives rise to achieving the economies of scale. Moreover, this feature is primarily linked to the basic network configuration (Shi and Gregory, 1998).

Learning ability. Learning in a manufacturing network composed of transferring internally generated knowledge – e.g. acquired in the home facility – to the other facilities in the network (Colotla et al., 2003). Learning ability is mainly derived from the coordination of dispersed facilities (Shi and Gregory, 1998). Usually, this starts in a facility as it develops processes and technologies, and emphasises lateral knowledge flow in the network. Hence, the degree of knowledge exchange, for example, product knowledge or process related knowledge, among the facilities of a manufacturing-network is the means of learning ability.

Mobility ability. Companies operating facilities in dispersed locations usually derive their advantage from a superior mobility ability through the transfer of products or processes between facilities; also from managerial skill mobility to accelerate the acquisition of skills, knowledge or culture (Miltenburg, 2009; Shi and Gregory, 1998). In order to realise the mobility within a manufacturing network, resources – such as technology or processes – must be duplicated (Kogut, 1990). Thus, mobility is higher when the facilities are able to produce the same products, or when the products produced in different facilities require identical processes and technologies. Therefore, the mobility is reflected by the degree of duplication of the activities in the multiple facilities.

In the remaining of this paper, we shall apply the above-mentioned capabilities in order to map the management of activities in manufacturing networks of our studied cases, on the following ground. These capabilities have been recognised as important contributors to a firm’s network operation performances (Andrésen et al., 2012). Hence, are inherently tied to a manufacturing firms’ success, other way round, failure. Therefore, paying attention to these dimensions will allow us to interpret the reshoring motivations within the realm of a company’s goal-oriented decisions.

MethodThe nature of our research question suggests an explicit aim to gain an insight into the phenomenon of reshoring (empirical evidence is still scarce), and to explore its linkage to the capabilities derived from the operation of networks. In doing so, by referring to the literature we identified the attributes representing the network-manufacturing capabilities. From the context, we seek to gain a better understanding of the relationship between the operations of intra-firm networks and reshoring. Therefore, we engage with a disciplined iteration between theoretical attributes and the empirical data from a particular context (Ketokivi and Choi, 2014). A case-study approach was chosen to gain a detailed understanding of the study phenomenon. Case research has the potential to disclose better an understanding of how the activities performed in the decentralised environment (Ellram et al., 2013). Moreover, unconstrained by the rigid limits of questionnaires and models, case studies can give rise to new and creative insights and have a high validity with practitioners (Voss et al., 2002). A qualitative research is essential for analysing a specific situation in greater depth and detail (Eisenhardt, 1989; Rowley, 2002).

Based on the work of Miles and Huberman (1994) and Yin (1994), we adopted a multiple case study designs to increase the possibility of generalising findings in an analytic way. Moreover, multiple cases enable broader exploration of research questions (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). We have employed a multi-case method focused on a single unit of analysis, i.e. an intra-firm manufacturing network for a product/product group. The dispersed facilities of an intra-firm network are held exclusively under the focal firm, thus allowing us to gain in-depth insights into the dimensions of our interest.

Case selectionWe adopted a theoretical sampling method, in which cases are selected because they are particularly suitable for illuminating and revealing an unusual phenomenon, thereby extending relationships and logic among attributes (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). Case selection was performed in two actions, by adapting the sampling suggestions of Miles and Huberman (1994). Firstly, manufacturing companies in geographical proximity – headquartered in Madrid and Stockholm – were considered as potential candidates. In addition, sampled companies had maintained a relationship with our institutions. In fact, accessibility is very important (Patton, 1990), to get the best data access in order to learn from retrospective cases. The choice of cases is instrumental to the access to the companies and the investigation of whether reshoring is due to beyond cost factors (Hartman et al., 2017). In this vein, we approached the companies those had extensive offshored manufacturing experience and also faced challenges in operating their dispersed facilities and subsequently reshored/ backshored some or all of their offshored activities; i.e. similarity in context (Johnston et al., 1999).

Secondly, cases were selected based on their willingness to participate, that is, organisations that had communicated the information openly. Taking into account both the time and cost needed to conduct the case studied, and the purpose i.e., gaining an insight into the failure-in-offshore cases, companies were chosen for the likelihood of offering theoretical insight (Eisenhardt and Graebner, 2007). We have selected three manufacturing companies, first two companies’ headquarters in Spain and third one in Sweden, for an in-depth analysis to understand the relevance of network operations to the reshoring phenomenon while ensuring that views were captured from multiple business areas. The number of cases is considered acceptable for a multiple case-study research (Barratt et al., 2011); meanwhile, a small sample was chosen because of the expected difficulty in obtaining comprehensive information from a large number of cases. Further, current investigation is neither prone to the sector of manufacturing nor to the ‘country of origin’ effect.

Data collectionData were collected with semi-structured questionnaires and a study of company reports. The data collection was compiled by interviewing the manager involved in the manufacturing strategy formulation and/or implementation, the international operations manager, and the plant manager of each company. All respondents were selected as the most appropriate informants because of their involvement and/or in-depth knowledge of manufacturing in their dispersed facilities. This reduces the likelihood of misinterpretation and increases the availability of multiple viewpoints. To minimise differing and incomplete views (e.g. Case-C, differing views on product quality – home vs host centric), we asked to re-discuss the possible reasons, which led to convergence (Voss et al., 2002).

To improve rigour and increase validity, a set of questions was prepared in advance [Supplementary file]. Together with an introduction letter, questions were sent to each interviewee before the interview session. Multiple interviews were conducted, in which an individual interview typically lasted from 2 to 4 h. Interviews began with the introduction of the basic information of the companies and continued with open questions related to the operation of dispersed facilities. There were two researchers present at each interview. Interviews were recorded and transcribed literally. To avoid the misinterpretation of facts and figures, case descriptions were sent back to the interviewee. After several iterations of correction, the case reports were finalised. This established the chain of evidence and guaranteed construct validity (Yin, 2009).

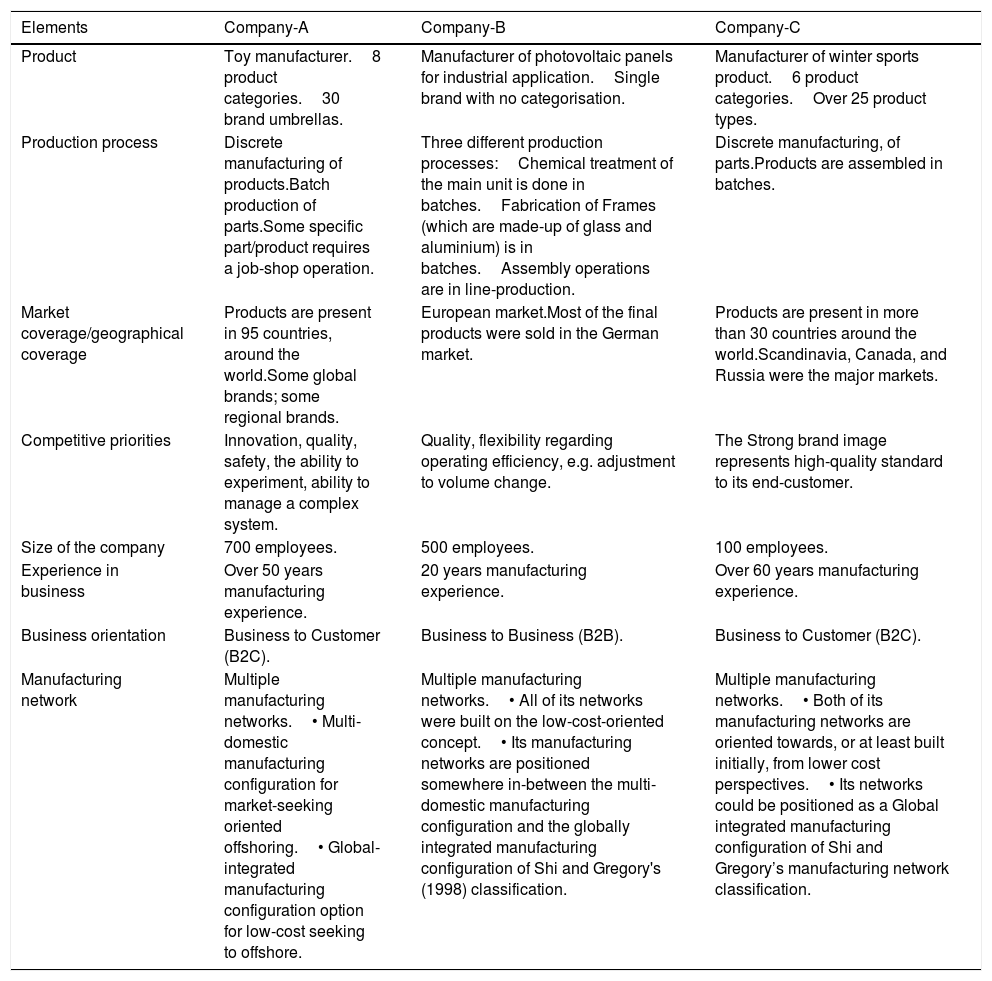

Based on the written description of our case studies, the key characteristics of the companies are presented in Table 2. Company names are disguised to maintain anonymity, to comply with their request. Studies were carried out between February-May 2015, and February–April 2016.

Key characteristics of studied case companies.

| Elements | Company-A | Company-B | Company-C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Product | Toy manufacturer.8 product categories.30 brand umbrellas. | Manufacturer of photovoltaic panels for industrial application.Single brand with no categorisation. | Manufacturer of winter sports product.6 product categories.Over 25 product types. |

| Production process | Discrete manufacturing of products.Batch production of parts.Some specific part/product requires a job-shop operation. | Three different production processes:Chemical treatment of the main unit is done in batches.Fabrication of Frames (which are made-up of glass and aluminium) is in batches.Assembly operations are in line-production. | Discrete manufacturing, of parts.Products are assembled in batches. |

| Market coverage/geographical coverage | Products are present in 95 countries, around the world.Some global brands; some regional brands. | European market.Most of the final products were sold in the German market. | Products are present in more than 30 countries around the world.Scandinavia, Canada, and Russia were the major markets. |

| Competitive priorities | Innovation, quality, safety, the ability to experiment, ability to manage a complex system. | Quality, flexibility regarding operating efficiency, e.g. adjustment to volume change. | The Strong brand image represents high-quality standard to its end-customer. |

| Size of the company | 700 employees. | 500 employees. | 100 employees. |

| Experience in business | Over 50 years manufacturing experience. | 20 years manufacturing experience. | Over 60 years manufacturing experience. |

| Business orientation | Business to Customer (B2C). | Business to Business (B2B). | Business to Customer (B2C). |

| Manufacturing network | Multiple manufacturing networks.• Multi-domestic manufacturing configuration for market-seeking oriented offshoring.• Global-integrated manufacturing configuration option for low-cost seeking to offshore. | Multiple manufacturing networks.• All of its networks were built on the low-cost-oriented concept.• Its manufacturing networks are positioned somewhere in-between the multi-domestic manufacturing configuration and the globally integrated manufacturing configuration of Shi and Gregory's (1998) classification. | Multiple manufacturing networks.• Both of its manufacturing networks are oriented towards, or at least built initially, from lower cost perspectives.• Its networks could be positioned as a Global integrated manufacturing configuration of Shi and Gregory’s manufacturing network classification. |

Data analysis was carried out simultaneously with the data collection, which provides the flexibility to make relevant adjustments throughout the process (Eisenhardt, 1989). The decision rule maintained for data entry into our analysis was: any change reported was verified by a document or at least one other respondent. There was high agreement among the respondents about the critical issues of how the network operation was performed, and how they faced complexities.

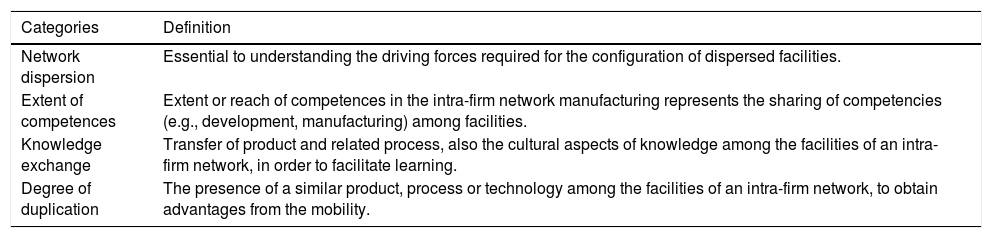

Data were analysed in the light of the methodology proposed by Miles and Huberman (1994), which consists of three main phases. (i) Data reduction: Reducing the qualitative data through coding. In the coding process, categories were selected based on the attributes linked to the network-manufacturing capabilities, as outlined in Table 3. Moreover, the information about configuration (vis-à-vis the elements of Table 1) and the operation of activities were interpreted to perform the detailed coding. (ii) Data display: Each case is presented in the within-case analysis section, with headings: offshore decision scenario, operation of activities in intra-firm network, and network-manufacturing capabilities. Moreover, a table was created to illustrate the capabilities across all cases. (iii) Drawing conclusions and verification: Using four selected dimensions of capabilities, a cross-case comparison was conducted. To increase the reliability of the findings, an explanation of each case was tested twice by looking into the field notes to see how well supported they were.

Basic definition of coding categories.

| Categories | Definition |

|---|---|

| Network dispersion | Essential to understanding the driving forces required for the configuration of dispersed facilities. |

| Extent of competences | Extent or reach of competences in the intra-firm network manufacturing represents the sharing of competencies (e.g., development, manufacturing) among facilities. |

| Knowledge exchange | Transfer of product and related process, also the cultural aspects of knowledge among the facilities of an intra-firm network, in order to facilitate learning. |

| Degree of duplication | The presence of a similar product, process or technology among the facilities of an intra-firm network, to obtain advantages from the mobility. |

The quality of any case study research depends on four different criteria: construct validity, internal validity, external validity, and reliability (Yin, 2009, p. 40). Construct validity has been met by the measures for the concept being studied, i.e. capability dimensions from the literature, definition of the unit of analysis, and having key informants review the case report (Yin, 2009). Internal validity only applies to experimental studies (GAO, 1990), and the present study’s exploratory purpose for not addressing the internal validity. External validity of case studies concerns the analytical generalisation, not to generalise statistically (Yin, 2009, p. 10). A multiple case study design provides breadth; each case serves as a distinctive experiment and as an analytic unit. Hence it has higher external validity than single cases (Voss et al., 2002). Reliability is concerned as to whether the same results can be obtained by repeating the data collection procedure (6 and Bellamy, 2012). These have been assured through the use of a case study protocol – to standardise the investigation – and by developing a case study database (Yin, 2009).

In addition, triangulation – multiple perspectives to converge on the phenomenon – has been met by interviews from different informants with different responsibilities, and by multiple researchers involved in gathering and interpreting the data (Patton, 1999). Also, the interview data were supplemented by other sources, such as company presentations, documents and the annual report (Miles and Huberman, 1994).

Within-case analysisCompany-AOffshoring decision scenarioStarted in 1957, Company-A is operating successfully in its facility in Spain where it had the full capability to manufacture products from concept development, design/sketches, mould creation, to production and assembly operation. Over the last decades, the company experienced a steady increase in sales (163,770 K€ in 2005–2006 to 247,896 K€ in 2014–2015). As part of its continuous improvement initiative, during 2008–2009 the company decided to start manufacturing activities in Mexico and China. The facility in Mexico – proximity-to-market oriented offshoring – was to serve the regional market with reduced logistics-related costs. In order to consider the local market requirements, there were some co-development of products with the home facility. The facility in China – low-cost production oriented offshoring – was to achieve the benefits of the lower-cost of manufacturing inputs. The final products (bicycles and tricycles for kids) were to serve the European customer. This facility was designed to manufacture according to the home-based development requirements; hence, the network decision intended to keep the core competencies internal to the company.

Operation of activities in intra-firm networkThe facility in Mexico was equipped to manufacture and test components, and to assemble final products. The home facility based management focused only on controlling the raw materials (e.g. purchasing, inbound transportation, raw material inventory) of some selected products. This choice was to obtain the scale benefits in purchasing. The coordination of other activities was through the formal structure, e.g. “formal reporting structure for any changes in the production schedule” as mentioned by the plant manager, hence mostly through impersonal communication. To date, Company-A is operating this facility in its international manufacturing context.

The facility in China was equipped with production machinery, testing and assembly as well. The raw materials were usually sourced from regional markets. Product development activities were located at the home facility. In addition, purchasing, production management, inventory and transportation activities were co-managed by the home facility. The coordination of purchasing, inventory and transportation was in a formal structure, which was to exchange the standard requirements. However, the centralised decision regarding the production management, i.e. to ensure the quality standard, was in combined structure of formal and informal (personal communication) coordination. Despite this, with the increase in pressure to be competitive, Company-A suffered from poor operational performance in processing orders, transportation lead-time, and customer service of products manufactured in Chinese facility. As mentioned by the international operations manager: “….it became difficult to ensure the quality and the delivery lead-time”. The fact was that, in order to ensure the product quality, the company witnessed a higher than expected number of personal and impersonal communications. Moreover, exposed to the changes in market requirements, shorter delivery lead-time became critical. As mentioned by the international operations manager, “we have been trying to reduce the usual lead-time from 90 days to 45 days, …… but without success. This restricts a quicker response to the changing nature of customer demand”. In 2014, Company-A’s management team decided to bring back the production from the facility in China to its home facility in Spain.

Network-manufacturing capabilitiesAccessibility. In locating the facility in China, the drivers for offshoring the production were the advantages of lower labour and raw-materials costs as compared to the home location. However, some changes in the advantage were apparent. As mentioned by an interviewee, “…we have observed an increase in wages in China, ……though the change in the wage rate was not so high, the added complexity in getting the right products on time leads to an overall higher cost”. Hence, Company-A experienced partial benefits from the accessibility due to the changes in strategic resources, i.e. increased labour costs at a price higher than the expected level.

Thriftiness. According to the design of the low-cost oriented production network, the home facility held development, purchasing and production competences while the host facility held production competence. However, in the operation of dispersed facilities, the advantage regarding economies of scope was indistinct due to the problem raised with excessive communication. Company-A management stated, “….managers (of the home facility) need extra travel to ensure the product quality”. This reflects the low reach of production competencies in this network-manufacturing. A poor level of thriftiness ability is depicted here, as the advantages of centralised product development and purchasing were diminished by the weak integration between the home and host facilities.

Learning. The home facility was responsible for product development and design, hence provided knowledge to the network. Knowledge transfer in the opposite direction was not apparent in Company-A’s network, which is reflected by the international operation manager stating, “…it (network management) was not designed to train the host employees in the home or another facility. ….Besides, the home-based managers mostly hold the responsibility for the output quality”. Hence, the network manufacturing of Company-A suffered from the lack of active participation of all facilities. Furthermore, as the products produced in multiple facilities were completely different, there was no possibility to bring production employees from another facility to provide in-depth process related knowledge. Thus, interdependency between facilities is needed to increase their knowledge sharing.

Mobility. According to the design of network-manufacturing, i.e. considering the focus of a scale producer and product portfolios are different for each facility, Company-A stated that they have no mobility of product or process.

Company-BOffshoring decision scenarioCompany-B’s manufacturing activity was originated in the U.S. In order to serve the European market, in the early 1990s, the company started to manufacture with headquartered in Spain. This facility was completely independent, and its further expansion and diversification were owned by the home facility in Spain. After ten years of successful business, in response to increased product demand, the company decided to expand its manufacturing from two lines to ten lines of production. As part of this, they started a Greenfield facility in China and a joint venture facility in India. These choices were mainly focused on the lower-cost of production inputs, since the final products were distributed from its home facility to serve the European market.

Operation of activities in intra-firm networkThe offshore facilities of Company-B were equipped with standardised machinery for production, testing and assembly units. Raw materials were sourced mostly from regional markets. Before the offshoring, Company-B had production process standardisation for transferring the product lines. The coordination of activities was designed to maintain the operation of network facilities through pre-established work procedures. As the management states, “…when we developed the offshoring strategy, it was expected to manage the facilities only through a formal structure”. However, for the time being, the quality of the products coming from the offshore facilities was lower than that of the home facility. In order to maintain the quality standard, the centralised management was forced to change the coordination steps. Managers needed to travel from the home to the host facility, which were intended to transfer production competences to host employees. This showed a preference for informal means of coordination to mitigate the complexities rapidly. However, there were still quality defects in the products from offshore facilities, and those required to be processed again in the home facility. As stated by the international operations manager, “….just after a few years, the management of our company realised that we had already doubled our coordination and quality assurance efforts compared to its starting period. However, the final product remains below the quality standard; some products even have to be processed in our home facility again”. Hence, the issues of the network-manufacturing operation, i.e. an excessive coordination to maintain the product quality, was driver for the reshoring decision.

Moreover, delivery lead-time was also crucial to utilise the global production capacity of Company-B. Often, in cases of increased demand, the centralised management had to manage the trade-off between long-haul transportation versus the high weight-to-cost ratio of the product. Which is reflected by “…there were insufficient network-level flexibilities to deliver products on time”.

Network-manufacturing capabilitiesAccessibility. The offshore facilities of Company-B aimed to increase its production capacity as well as to attain benefits of lower cost. It is remarkable that the access regarding a low-cost production input was deemed capable here since the company did not witness any change in costs. However, the functionality of its international manufacturing largely strived for other dimensions of the network-manufacturing capabilities.

Thriftiness. Company-B had invested in machinery aimed to ensure required quality products from offshored facilities. Internally, the company had the competence to process its high-tech products. This was reflected as the plant manager stated: “…our (product’s manufactured in Spain) quality level was much closer to the quality of market leader”. The reach of know-hows (production and quality control) to offshore facilities became the most important issue in order to make the network manufacturing a success. However, excessive travel from the home to host facilities, as well as an additional task performed in the home facility indicates an insufficient level of competence transfer between facilities. As mentioned by the plant manager, “… sometimes we had to perform extra work (on products coming from other facilities) to make them saleable”.

Learning. Though the home-centric management put extra administrative efforts (through travel and communication) to transfer the process-related knowledge, the results were not reflected in final products. As highlighted by the management, “…we have several unplanned trips, …however, similar types of problems exist”. Hence, limitations in knowledge transfer appear as a serious impact on the learning capability, because the product (host’s) quality remained below the standard level.

Another interesting observation is the cultural aspects of knowledge transfer difficulties. This is highlighted by the international operations manager stating, “cultural differences and differences in the mindset cause differences (between home and host employees) in ways-of-doing. …for example, the host managers had a general tendency to say ‘yes’ before understanding what we said. However, we found a similar problem… later again”. Therefore, the network management has suffered from the working attitude of knowledge receivers. Hence, managing manufacturing activities in the facilities of Far-East locations gave rise to issues of human aspects as well as cultural differences that were also crucial for knowledge transfer.

Mobility. The primary condition for obtaining advantages from the ‘mobility’ within a network-manufacturing is seen here in the case of Company-B. That is, according to network configuration, there were duplications of production processes among its facilities. Though there were managerial movements – both, planned and unplanned travel – from the home to the host facilities, Company-B experienced a low degree of operating efficiency. The management of the company stated, “… similar types of problems in their products (dispersed facilities) continued, as in the early days of offshore manufacturing”. Hence, network-manufacturing ability to create learning through the ‘mobility’ was poor.

Company COffshoring decision scenarioCompany-C was established in 1944, headquartered in Stockholm, Sweden. Between 1957 and 1967 it made significant expansion in home location, and in early 1980s, ownership was changed. Starting from a very low level with limited experience, it showed a steady increase in turnover (e.g. 7025 K€ in 2007 to 20,104 K€ in 2015). In the early 2000s, the company implemented two offshore outsourcing (joint-venture) decisions. One was to manufacture two different winter sports products in Lithuania, and another to manufacture a winter sports (different from Lithuania) product and a standard game product in China. Primarily these decisions were to reduce the total cost of manufacturing. Since the final products were distributed from its home facility to its European customers, its network-manufacturing were viewed as a low-cost production decision (Ferdows, 1997b).

Operation of activities in intra-firm networkBoth of its offshore facilities were equipped to manufacture all parts of the final product. R&D and product design activities were located in the home facility. The centralised management of Company-C focused on coordinating its activities: purchasing and raw material, production, and logistics management for both of its offshore facilities. Such coordination involved both direct and indirect support on different levels.

The purchasing and raw-material activities were continually monitored by a host-centric purchasing manager. Moreover, there was centralised coordination to ensure the frame agreement of purchasing in its network-manufacturing. However, in dealing with its Far-East facility the company faced difficulties in managing raw-materials. “There were some unexpected changes in the raw material inputs” – as mentioned by the international operations manager. Usually, this type of problem was managed through informal communication. On the other hand, for the facility located nearshore, the company preferred to select a home-location based supplier in order to solve such types of difficulties.

The coordination of production-related activities was mainly to transfer the design concept developed at the home facility. This was facilitated through the standardised production process with comprehensive instructions. Despite this, there were products lacking in quality that were distributed to the European based warehouse or sellers. For example, “durability of stickers, proper positioning of stickers, colour fade-offs” as mentioned by the international operations manager. Potential reasons for these types of quality defects were deduced from the comments of the plant manager, “unexpected raw-material inputs, frequent changes of production workers, instructions were not followed”. Usually, problem-oriented complexities were managed through direct communication from the home facility. However, these incurred additional costs to the total cost of manufacturing.

Products manufactured in dispersed facilities were delivered directly to the sellers or distributed from a warehouse located near the company’s home facility. The distribution of final products from the facility in China to the majority of its European customer bases required six to eight weeks lead-time. Some products had to be returned due to unexpected errors in the product. Moreover, as a manufacturer of sports items, Company-C is exposed to the seasonality of three to four months of seasonal products. Thus, a delivery lead-time of 6–8 weeks (from the Far-East facility) was a long time. This forced the company to maintain a safety stock. However, it was not worthwhile to maintain large safety stocks for such seasonal products.

At a glance, the company experienced challenges to ensure the quality of the raw material and also to manage the product quality with the expected lead-time. The fact was that, on the one hand, in order to maintain the quality standard additional administrative efforts were evident; on the other hand, unexpected changes in the raw-materials and long delivery lead-time led to the overall disadvantages for the intra-firm network manufacturing.

Network-manufacturing capabilitiesAccessibility. The initial drivers for the network configuration were the advantage of lower labour and raw materials costs. In managing its network-manufacturing, the company experienced the difficulty of obtaining raw materials of consistent quality. Company-C’s management stated that “… in the Far-East facility, though there was a person assigned to purchasing…… we observed unexpected raw-materials inputs. Managers (home facility) had to travel to support them”. In addition, the inconsistency of production employees was evident, “it was unexpected that… in the Chinese facility, there was inconsistency in factory workers”. Apart from the access to cheaper production inputs, Company-C strived for a consistent quality of raw materials and the stability of labour. The consequences of these challenges of accessibility were reflected in the final product, as well as in other dimensions of network-manufacturing capabilities such as learning.

Thriftiness. As the network-manufacturing strategy developed, the home facility of Company-C provided the R&D, product design and procurement competencies to the facilities in their network. Though other facilities were designed to have the production process competencies, production coordination for the Chinese facility required excessive attention. As stated by the international operations manager, “instructions were not interpreted in the same way, which required detailed interpretations, …thus leading to extra administrative efforts”. Hence, there was a low reach of competences in the dispersed facility.

Learning. Centralised mechanisms to transfer the product design and production-related knowledge involved both formal – i.e. written instructions – and informal/direct travel of the production manager. As mentioned by the international operations manager, “the production manager from Sweden, usually travels to the offshore facilities. This is to check the activities according to the written instructions, … also to demonstrate the production to the employees”. Hence the home facility conducted a high-reach product development activity and generated knowledge to the dispersed facilities in the network. However, according to the comment of the plant manager, “production instructions were not followed….…ensuring the quality standard is difficult”, a low degree of learning is reflected. Moreover, as noted earlier, the inconsistency of the production employees resulted in an overall diminishing rate of learning in the Chinese facility.

Mobility. The degree of duplication is the prerequisite to achieve network-level mobility. Here in the case of Company-C, the network manufacturing showed limited mobility ability. This is because the individual facilities were dedicated to manufacturing a different product or product groups. As stated by the interviewee, “it is not possible to train the employees (e.g. Chinese) in another facility (e.g. Sweden)”.

Cross-case analysis and discussionEven if the three studied companies are not fully similar, regarding offshoring and reshoring they have a close similarity; hence knowledge can be deduced from them. All three companies offshored their activities to extend their capacity and also to reap the benefits of lower production costs from Far-East locations. The studied companies acknowledged that product quality and network integration were the major challenges they had experienced in their network manufacturing. Concerning the extent of competences, failure to establish the reach of competences in the dispersed facilities was apparent from the additional work performed – to fix the defects – in the home facility (Company-B). Likewise, Company-A demonstrated the limited integration of the home and host facilities which restricts the advantages of centralised management of R&D and purchasing. Concerning knowledge exchange, studied companies suffered from poor learning abilities due to the one-way transfer of knowledge, limited participation of the host employees, the inconsistency of production employees, and cultural and human aspects. Each of these issues is likely to affect the quality of the products manufactured in the dispersed facilities. Therefore, the reshoring of host facilities to the home locations was viewed here as the ease of knowledge exchange within an acceptable reach of activities.

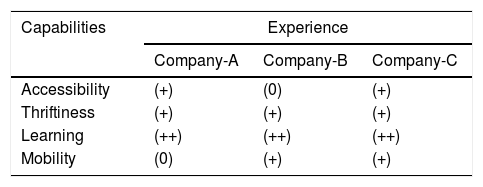

The most important insight that the studied companies disclosed was that they experienced managerial challenges throughout their network-manufacturing journey. Accordingly, this study discloses interesting points in terms of level of network-manufacturing capabilities. Table 4 displays the level of relevance to the choice of reshoring regarding the different capabilities analysed. It demonstrates the influence of the capability dimensions from ‘not manifested’ to ‘high relevance’. Interesting for this paper, all companies mentioned the role of thriftiness and learning capabilities in their reshoring decision. In the following, we will present the results on the state of capabilities in detail.

Findings from the case study.

| Capabilities | Experience | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Company-A | Company-B | Company-C | |

| Accessibility | (+) | (0) | (+) |

| Thriftiness | (+) | (+) | (+) |

| Learning | (++) | (++) | (++) |

| Mobility | (0) | (+) | (+) |

‘0’, ‘+’, and ‘++’ indicate the level of relevance to the choice of reshoring: ‘not manifested’, ‘moderate’ and ‘high relevance’, respectively.

Accessibility. As discussed in the offshoring decision scenarios in section 4, the three studied companies (reshored facilities) focused heavily on access to the lower-cost of production inputs. That is, in their strategy for international manufacturing, the network dispersion decision was made concerning either cheap materials and/or a lower wage rate compared to their facilities in the European region. Regarding accessibility, Company-A experienced a small drop in the wage-gap, and Company-C experienced quality variations in production inputs with targeted costs. The fact is that both of these companies struggled to evaluate constantly whether the expected gap continued and how to sustain the target accessibility. For example, apart from the access to a lower cost-of-production, Company-C strived for access to the availability of skills to maintain the consistency in raw materials. Hence, once an offshore decision has been made it is necessary to improve the capabilities in strategic resource access.

Thriftiness. All the studied companies have offshore manufacturing strategies to keep their core competences internal to the home facility. For instance, product design and development competences were fully internalised for all three companies. Hence, for the ‘thriftiness’ capability, with an emphasis on the economics of scope, know-how on production processes and quality control represent the important competences for other facilities in their network. Interestingly, all the cases display extra control mechanisms, very little network learning and economies of scope. In the case of Company-A, limited integration between home and host facilities acted as a barrier to achieving the advantage from the centralised management of R&D and purchasing; while, Company-B experienced additional work performed at the home facility in order to fix the quality problem, viewed as the low reach of process competences in the host facilities. Company-C provided extra effort on control, which was to protect the unexpected changes in raw materials and errors in the products. The analysis reveals that companies provide excessive efforts in integration and control in order to support the low reach of desired competences in dispersed facilities.

Learning. Learning, in the perspective of manufacturing in intra-firm dispersed facilities, is focused mainly on gathering and fulfilling functional knowledge to perform specific needs and is stimulated when one facility is affected by the knowledge of the others. From the experience of the three companies, we see how the challenges of network learning have been reflected in the product quality vis-à-vis the choice of reshoring. For Company-A, one-way knowledge transfer and a limited level of active participation of the host facility represents its knowledge exchange scenario. Company-B reveals a flawed learning ability which was reflected as inefficient transfer of engineering know-how; in addition, the cultural and human aspect was considered as a challenge for knowledge exchange. Company-C viewed the issues of production-related knowledge transfer as not only a lever for learning but also realised that the inconsistency of production employees made it difficult to achieve the long-term advantages from learning and competencies, thereby causing irregular quality defects. These findings showed that long-term network learning was an obvious influence on the company’s network manufacturing strategy, due to its linkage to the quality of products manufactured in dispersed facilities.

Mobility. The degree of duplication of products, processes or managerial skills between facilities is the prerequisite for the advantage from mobility in network manufacturing. The dispersed facilities of our studied companies were designed to have a fixed product or product group. Thus, to realise the ‘mobility’ within their network, the duplication of processes and managerial skills was to be expected. Despite the expected advantages of the mobility through the degree of duplication using the standardisation of processes, Company-B has not seen the benefit (e.g. operating efficiency) from ‘mobility’ in their dispersed facilities. Which was due to a lack of synergy between the facilities of its network. Hence, the mere existence of duplication possibility cannot ensure benefits from mobility; this also requires a strong synergistic effort in the network. Therefore, the relationship between the integration requirements and ‘mobility’ has been demonstrated by this case, indicating its influence on the company’s manufacturing strategy.

To sum up, the analysis reveals that network-manufacturing capabilities are indeed essential for the companies to infer the phenomenon of reshoring. The findings of the case study show that how the characteristics that explain the capabilities influenced the choice of reshoring. Most interesting, thriftiness and learning capabilities – as determined by the extent of competencies, network-integration and knowledge exchange – appear to be commonly linked to the reasons for reshoring. Companies saw that difficulties to open up and exchange required knowledge in the network has made decision makers more keen to bring back the disperse facilities, thereby ensuring the ease of improving overall quality.

Using the RBV of the firm, it has been argued that the competitive advantage of network operation should be gained through access to resources (from dispersed location) and the capabilities to deploy resources. For an intra-firm manufacturing network, the capabilities to deploy resources refers to the capabilities required to obtain advantages from the operation of dispersed facilities. An empirical analysis of our case study demonstrated how a lack of network integration and knowledge-exchange abilities, among others, emerge as the reasons behind the poor quality product, which forced the companies to reshore facilities. In this respect, according to the call of Fratocchi et al. (2016) to tie reshoring with RBV, this research has highlighted the firm’s inability to develop capabilities when operating in foreign contexts.

Conclusions and future researchIn recent years, research has been conducted to identify the drivers and/or motivators of reshoring. In this, scholars have identified quality and delivery lead-time, among others, as being the underlying problems that restrict companies in fulfilling their promises of manufacturing in global locations. Next, researchers opine that increasing difficulties in managing long-distance facilities nullify the benefits of the lower cost of production inputs in dispersed locations. The research encompassing these two important aspects linked to reshoring is limited. In this paper, we look at the phenomenon of reshoring from the viewpoint of operations or management of activities in dispersed facilities. It shows that how the decision of reshoring has relevance to the challenges of getting or developing specific capabilities; for instance ‘thriftiness’ and ‘learning’ as being the most interconnected.

The findings of this study contribute to extant literature on the management of multinational firms in general, and literature on international manufacturing in particular. First, the findings point to the importance of integration and knowledge exchange as a vehicle to ensure the quality of products from dispersed facilities. While the topic of product quality has mainly been treated from a production competence perspective, this study also indicates that excellence in each dimension of network-manufacturing capabilities refines overall product quality of global firms. Second, it shows that adoption of capability dimensions to the study of motivations for reshoring contributes to a better understanding of the relocation of manufacturing facilities from dispersed locations. Taken together the findings of this study shows that the adoption of network operations contexts, to complement the well-established motivations beyond cost factors, contributes to a better understanding of the reshoring of manufacturing back from the host location. In this way, we explicitly answer the call to examine “the effect of reshoring and insourcing experience on firm capabilities and their intentions to reshore and insource” (Foerstl et al., 2016; p. 505).

The findings also have valuable implications for practitioners. Firstly, the discussion of different capability dimensions and their implications on the reshoring phenomenon provides a picture of the necessary (lack thereof) capabilities that may help managers to prioritise the coordination of international manufacturing. For instance, organisations need not only to focus on target accessibility (e.g. lower cost of production inputs) but also to focus on managing or developing other dimensions of capabilities in order to maximise the benefit of international manufacturing. Practitioners can thus manage the dispersed facilities in a more target-oriented manner. This insight further supports the need for senior decision makers to move beyond the cost differential and work with the management of activities in network facilities in order to carefully evaluate what problems may be addressed. Secondly, the description of the operation of activities in dispersed facilities, drawing on the experience of failure cases, unveils how the difficulties in network operation could limit the target advantage of offshoring. Such difficulties might be due to the lack of coherence between strategy formulation and implementation. Therefore, an interplay among the decision-makers, managers involved in strategy formulation and international operations managers seems crucial here. Hence, organisations should actively manage the interactions among managers to increase the success rate, i.e. to obtain the advantages of offshore manufacturing.

There are several limitations of the study. First, the selected cases for this study are limited to the context of industries. Research should consider firms from several industries to introduce the possibility of industry-specific findings. Second, we have developed this research adopting a multiple case-study method, and a qualitative data analysis technique. Accordingly, we have considered potential approaches (such as, multiple interview at each company, interview and data analysing conducted by more than one researcher, having interview data cross-checked with the interviews, and having a detailed case study protocol) to ensure the validity and reliability of our findings. However, the statistical generalisation of larger set of population is not mentioned. Third, as a proposal for future research, we suggest longitudinal case studies on companies that have offshoring and consequent reshoring experience in order to understand the initial decision scenario and its consequences on reshoring decision, thereby gaining new and useful insights.

Moreover, even if our study accurately conceptualises problems related to network integration and/or knowledge exchange from some ‘failure in offshore manufacturing’ cases which were initially focused to either cost-saving or a proximity to market motive, the findings of this study do not explain the motivations of reshoring for other focused type of offshoring, e.g., access to skills and knowledge. In further investigations it might be possible to consider the initial objectives of going abroad in more detail, during selection and analysis of failure-in-offshore manufacturing. Lastly, our study provides interesting insights mainly based in failure cases of offshoring and how the lack of some abilities which ended up in reshoring. Findings of this research thereby broaden our understanding of the motivations beyond cost aspects. However, identifying and studying other perspectives would expand our knowledge of reshoring phenomenon. For instance, recent research has shown that (Grappi et al., 2018) the influence or the reaction of the home market might be behind some reshoring decision, and are worth investigating.

The help extended by European Commission through the EMJD program “European Doctorate in Industrial Management (EDIM)”, during the research is sincerely acknowledged.