The coexistence of hemifacial spasm and trigeminal neuralgia, a clinical entity known as painful tic convulsive, was first described in 1910. It is an uncommon condition that is worthy of interest in neurosurgical practice, because of its common pathophysiology mechanism: Neuro-vascular compression in most of the cases.

ObjectiveTo present 2 cases of painful tic convulsive that received treatment at our institution, and to give a brief review of the existing literature related to this. The benefits of micro-surgical decompression and the most common medical therapy used (botulin toxin) are also presented.

Clinical casesTwo cases of typical painful tic convulsive are described, showing representative slices of magnetic resonance imaging corresponding to the aetiology of each case, as well as a description of the surgical technique employed in our institution. The immediate relief of symptomatology, and the clinical condition at one-year follow-up in each case is described. A brief review of the literature on this condition is presented.

ConclusionThis very rare neurological entity represents less than 1% of rhizopathies and in a large proportion of cases it is caused by vascular compression, attributed to an aberrant dolichoectatic course of the vertebro-basilar complex. The standard modality of treatment is micro-vascular surgical decompression, which has shown greater effectiveness and control of symptoms in the long-term. However medical treatment, which includes percutaneous infiltration of botulinum toxin, has produced similar results at medium-term in the control of each individual clinical manifestation, but it must be considered as an alternative in the choice of treatment.

Desde su descripción en la literatura en la década de 1910, la coexistencia del espasmo hemifacial y la neuralgia trigeminal, conocida como tic convulsivo doloroso, es una entidad poco frecuente y al mismo tiempo interesante en la práctica neuroquirúrgica por su mecanismo fisiopatológico común, caracterizado por la compresión neurovascular en la mayoría de los casos.

ObjetivoPresentar 2 casos de tic convulsivo doloroso y realizar una revisión de la literatura breve de la literatura correspondiente; así como enlistar los beneficios que ofrece la cirugía y el tratamiento médico más comúnmente empleado con toxina botulínica.

Caso clínicoSe presentan 2 casos clínicos típicos de tic convulsivo doloroso, con ilustraciones representativas de imágenes por resonancia magnética de su etiología; así como la descripción de la técnica quirúrgica utilizada y del resultado inmediato en ambos caso y el seguimiento a un año. Se realiza una revisión de la literatura al respecto.

ConclusiónEsta entidad poco frecuente representa menos del 1% de las rizopatías por compresión vascular, vascular, que involucra en la mayoría de los casos al complejo vertebrobasilar por un curso aberrante dolicoectásico. El tratamiento estándar es la descompresión microvascular que ha mostrado la mayor eficacia y control a largo plazo de los síntomas. Sin embargo, el tratamiento médico que considera la infiltración de toxina botulínica ofrece resultados similares a mediano plazo en el control de cada manifestación clínica por separado, pero deben tomarse en consideración en la elección del tratamiento para cada caso individual.

In the decade of 1910, English and French doctors1 described a new clinical entity involving the co-existence of pain typical of trigeminal neuralgia (known as tic douloureux) and the presence of “convulsive” facial spasms; they sought an “epileptic” explanation for these involuntary movements. This description of simultaneous trigeminal nerve and facial disturbance is possibly the earliest. However, it was in 1920 when the term painful tic convulsif1 was coined by Cushing,1 referring to the co-existence of trigeminal neuralgia and hemifacial spasm as a result of the same pathophysiological mechanism.

ObjectiveIn this article, we present 2 cases of painful tic convulsive caused by neurovascular compression.

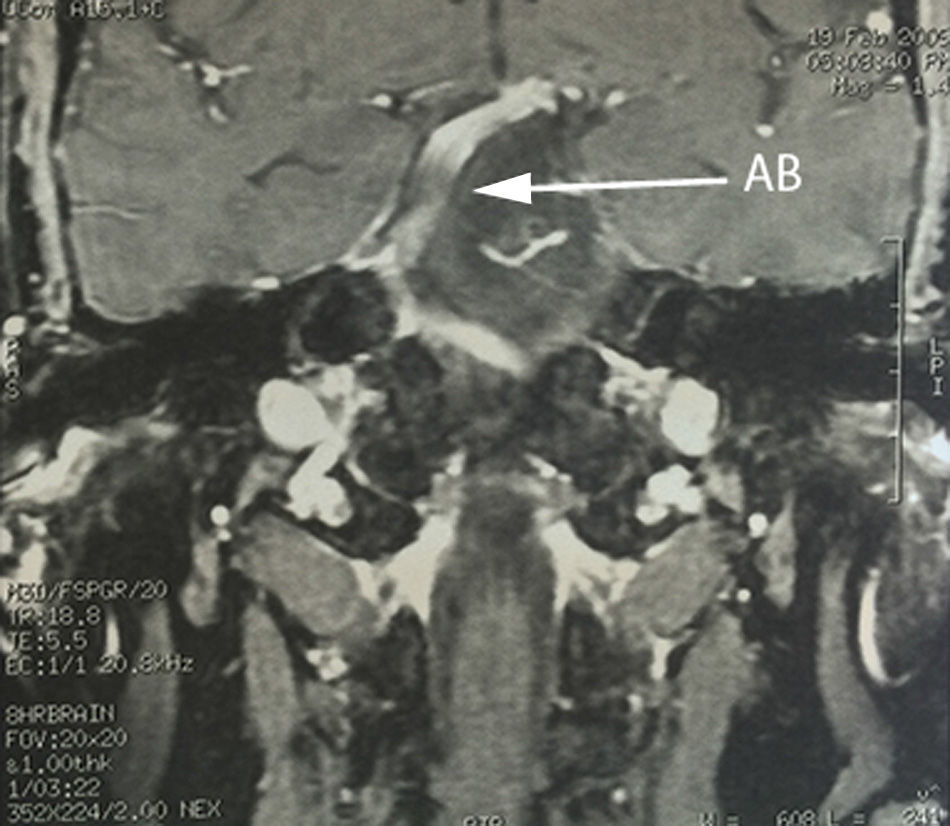

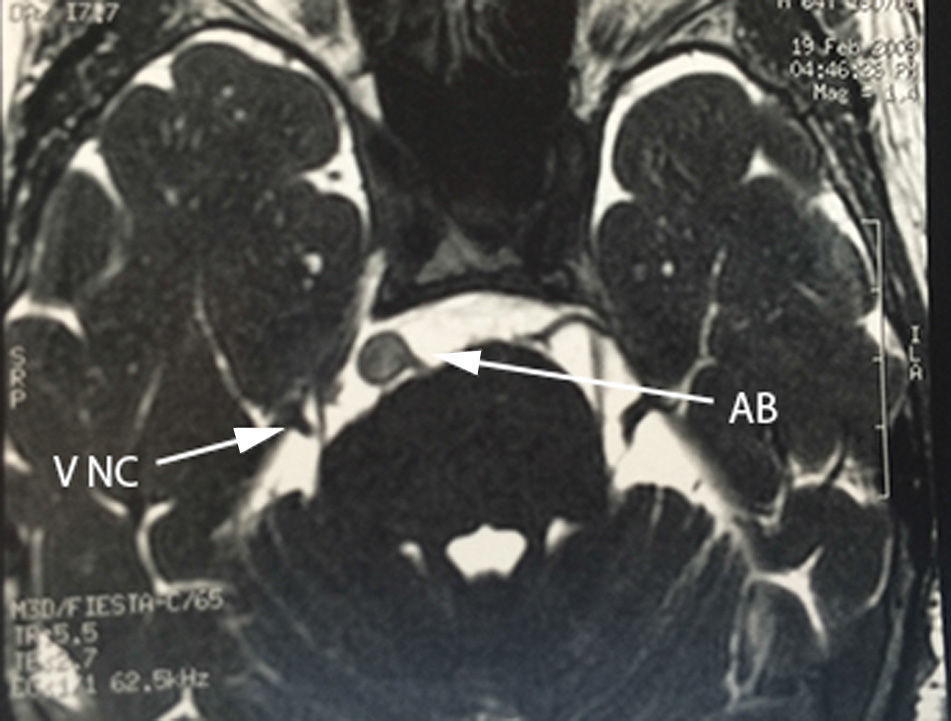

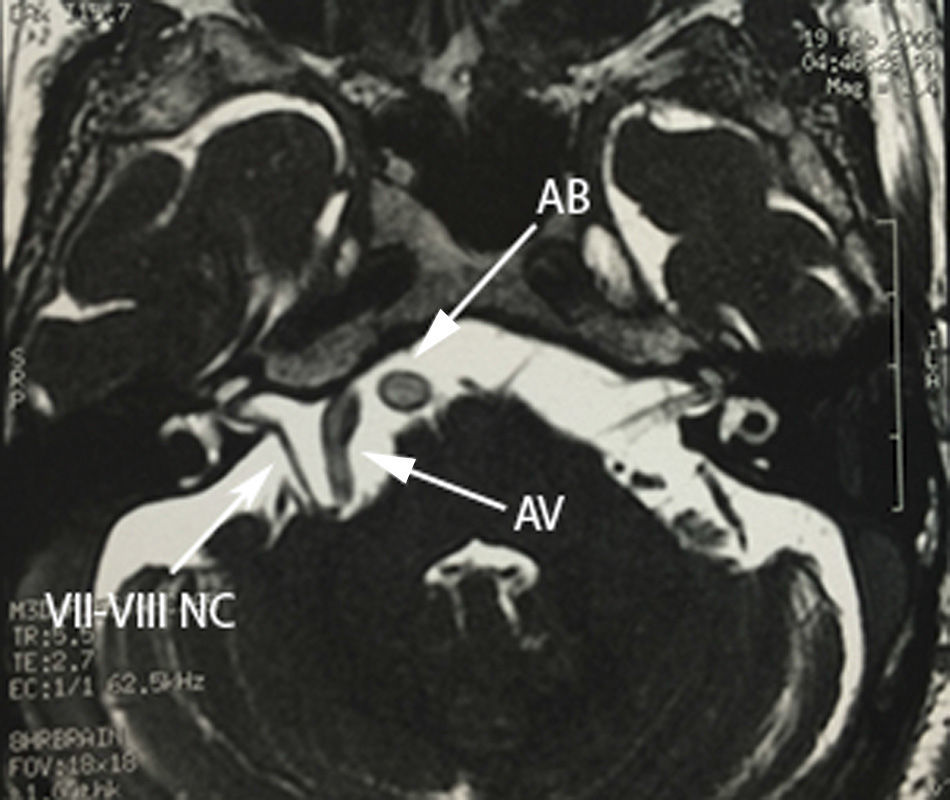

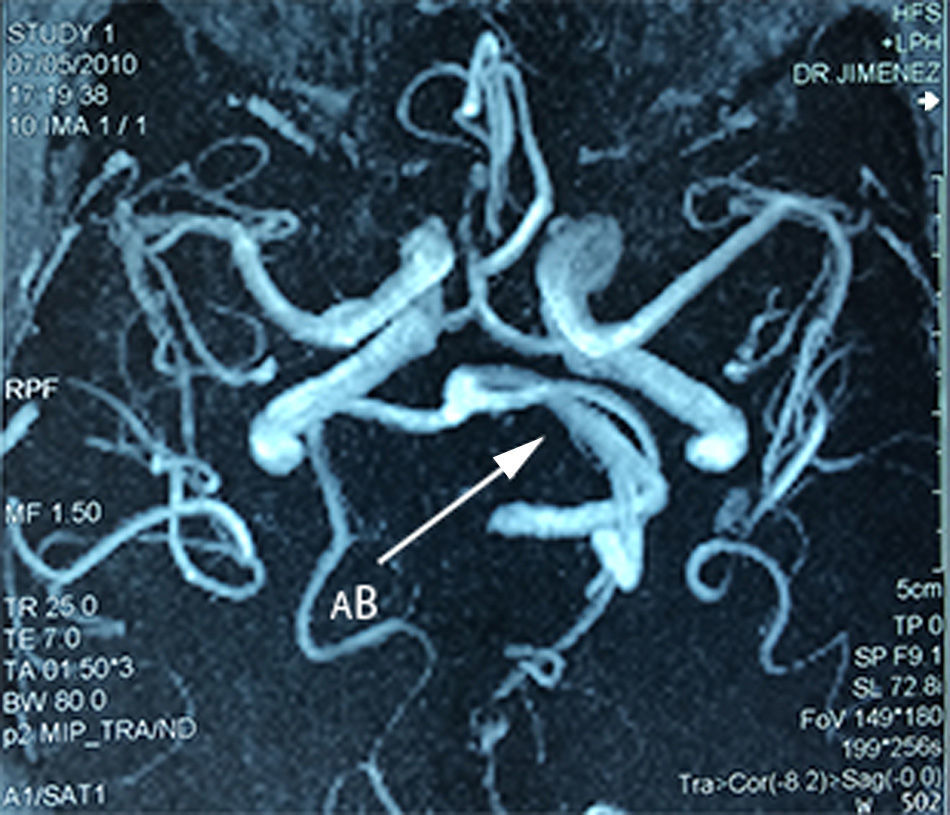

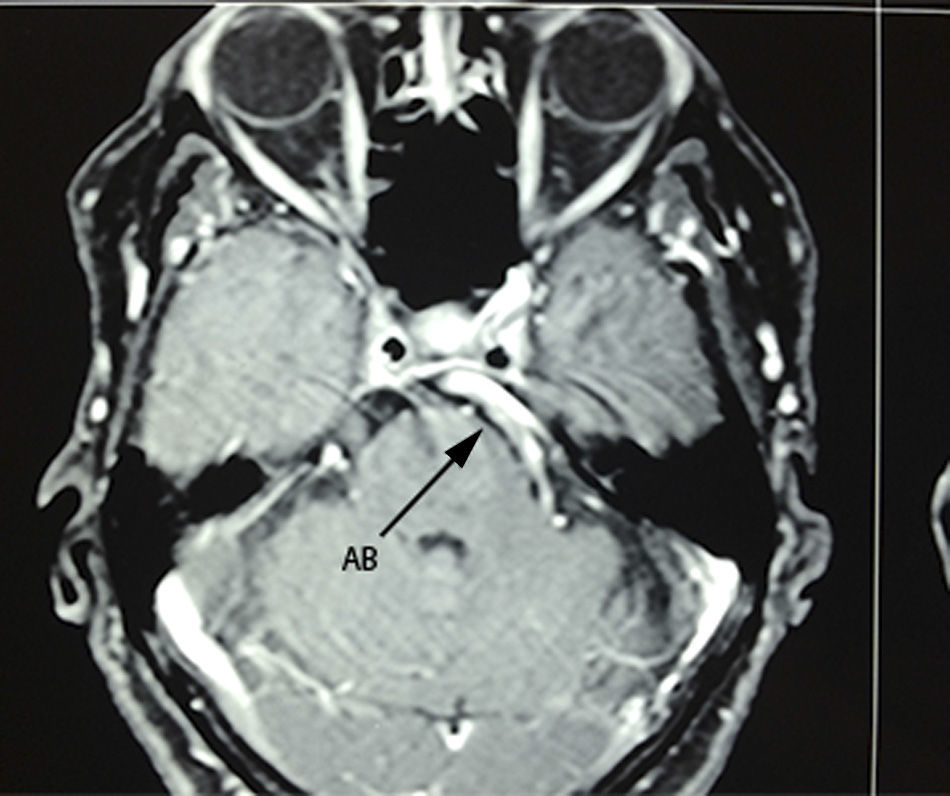

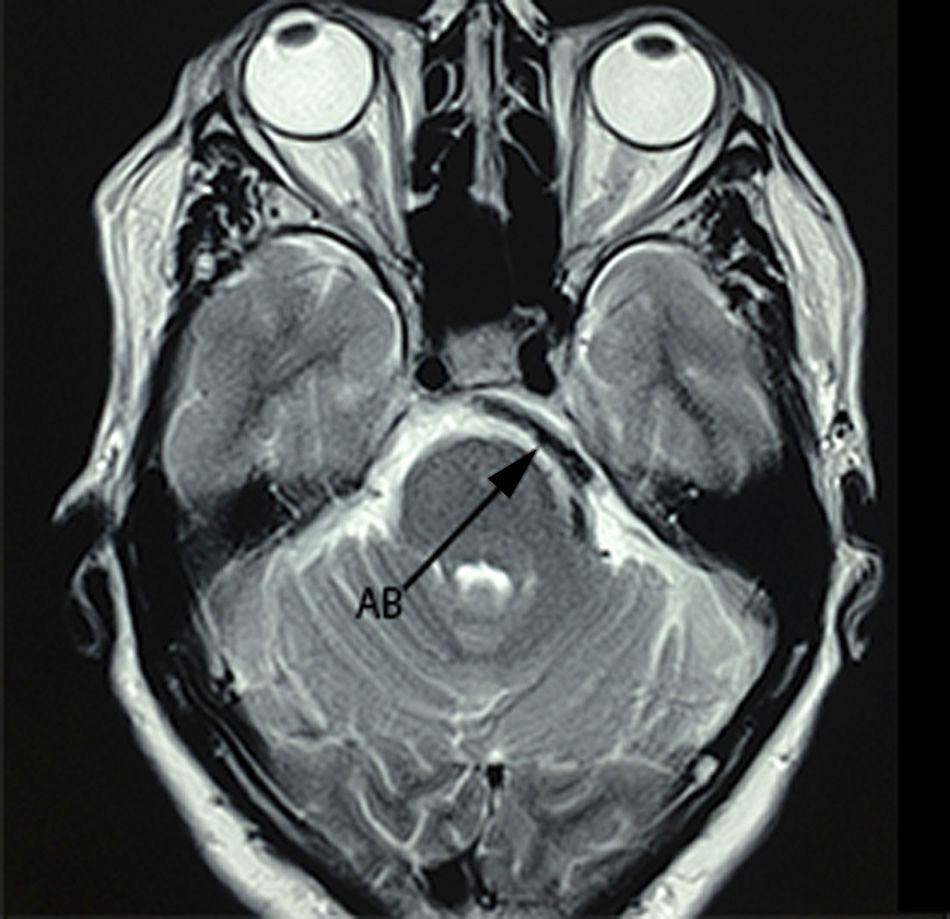

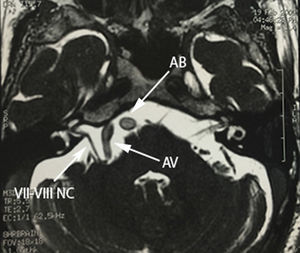

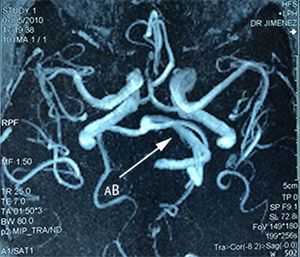

Case 1A 64-year-old male patient, with a 2-year history of systemic arterial hypertension and a 2 to 4-year history of Type 2 diabetes mellitus, presented with a 2-year history prior to admission of: predominantly right-sided bilateral tinnitus, a 1-year history of shooting, paroxysmal pain in ipsilateral V3, to which was added right-sided ipsilateral hemifacial spasm characterised by palpebral closure and elevation of the right labial commissure, triggered by blinking. Mild right-sided neurosensory hearing loss was identified during the study protocol, and the magnetic resonance study revealed dolichoectasia of the right vertebral artery and the basilar artery, which touches the trigeminal nerve in its cisternal segment and medial face, displacing it (Figs. 1–3). Surgical treatment by microvascular decompression was decided, using a right microasterional approach with Teflon, and compression of the vii-viii nerve complex by an ectatic basilar artery and compression of the fifth cranial nerve by the antero-inferior cerebellar artery.

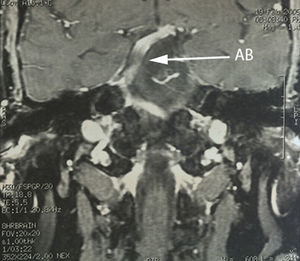

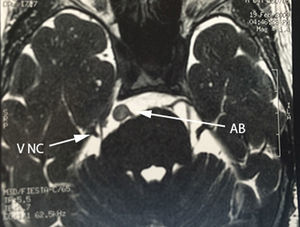

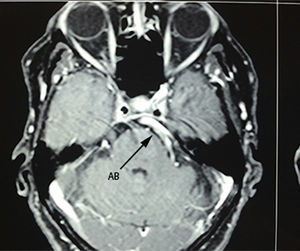

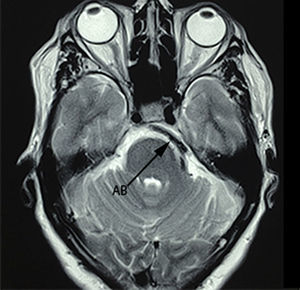

A 75-year-old female patient with a history of arterial hypertension, whose condition started 5 years prior to admission with shooting, paroxysmal pain in left ipsilateral V2-V3, to which was added ipsilateral hemofacial spasm over the course of 2 years, characterised by intermittent palpebral occlusion and elevation of the ipsilateral labial commissure. A study protocol was undertaken and a dolichoectatic course of the basilar artery was found on MRI that was compressing and displacing the cisternal portion of the trigeminal nerve, as well as absence of vii–viii complex before its entry into the acoustic pore (Figs. 4–6). Surgical management by microvascular decompression was decided with Teflon using a microasterional approach and direct vascular compression of the basilar artery to the vii–viii complex and of the vertebral artery to the trigeminal nerve.

Both cases’ symptoms were resolved, the paroxysmal pain involuntary movements stopped immediately after surgery with no hearing deficit or postoperative facial palsy. Likewise, neither patient presented recurrence of the pain or involuntary movements at one year's follow-up.

DiscussionThere are 3 series in the literature with the greatest number of painful tic convulsive cases. That of Han et al.,2 with a total of 1642 patients with hemifacial spasm and an incidence of 0.37% (10 cases) at one year's follow-up. Iwasaki et al.,3 with a total of 800 patients with hemifacial spasm and 400 with neuralgia of the trigeminal nerve, reported incidence of 0.66% (8 patients) of tic convulsive. Finally, the series of Cook and Jannetta et al.4 with the highest number of reported cases (11 patients), confirmed that the association of rhizopathies due to irritative hyperactivity has a very low frequency at 0.37–0.66% of all compressive neuropathies.2–5 With more than 20 years’ experience,5 5 cases of tic convulsive have been reported in our institution, added to which are the two cases we report in this article that were successfully treated. We used a microasterional approach and Teflon in all of the cases. In the most recent review reported in the literature, Jiao et al.,6 found a total of 71 cases published since 1920.

The most reported aetiology for this rare entity is vascular nerve compression,7,8 which in the majority of cases involves the vertebro-basilar trunk due to an abnormal or ectatic course, followed by the antero-inferior cerebellar artery and antero-superior cerebellar artery. It has been hypothesised that intimate contact, wear, and resorption of both histological surfaces (adventitial-epineural) are responsible for causing irritation and nervous hyperexcitability, which commonly involve sympathetic fibres, which would explain their appearance in periods of stress or anxiety.9 With regard to the temporality of symptoms, in most cases hemifacial spasm precedes the onset of trigeminal neuralgia; there is no clear explanation for this. Zhong et al.7 explain this phenomenon as having an anatomical basis, since the vertebral artery is closer to the vii–viii nerve complex than to the fifth cranial nerve. Consequently, abnormal displacement secondary to a dolichoectatic course of the arterial trunk places the vii–viii complex at greater risk. However, it is important to mention that, although vascular compression of the nerve elements is the most common aetiology involved in the development of this condition, it is neither essential nor unique in its genesis. In accordance with the above, involvement of the same nerve roots from tumour disease of the cerebellopontine angle has been reported. Interestingly, epidermoid cyst and not meningioma of the tentorial face of the cerebellum is the most commonly observed lesion after vascular disease. Zhang et al.8 review a total of 13 cases of painful tic convulsive reported in the literature since 1947, associated with the presence of a tumour in the posterior fossa, and discovered that 76.9% of cases were associated with the presence of an epidermoid cyst. It is interesting to observe that epidermoid cyst is the foremost tumour cause, above meningioma of the posterior fossa (the latter being more common), since the pathophysiological mechanism proposed for nerve involvement relates more to inflammation and the direct irritative effect of the keratin content of the cyst than the compressive effect of meningioma, which would explain the closer relationship that epidermoid cyst bears with the genesis of this double rhizopathy, compared to other local tumour aetiologies.10

A different entity, but with similar pathophysiology, has recently been reviewed by Dou et al.9: hemimasticatory spasm, defined by involuntary paroxysmal contractions of the unilateral masticatory muscles, with progressive hemifacial atrophy and shooting ipsilateral pain distributed trigeminally. This differs from painful tic convulsive in that the selectivity of the muscle spasm is confined to the muscles of mastication, principally the masseter, since, in hemimasticatory spasm vascular compression is confined to the motor root of the trigeminal nerve exclusively, in most cases by the superior cerebellar artery.

The recommended treatment for painful tic convulsive is microvascular decompression.2,7,8 However, careful study of each individual case by non-invasive imaging methods such as nuclear magnetic resonance with FIESTA and 3D time of flight (3D-TOF) sequences is the standard study protocol for detecting the aetiology of each specific case. The conventional approach in our institution, which involves minimal invasion technique by asterional microcraniectomy and dissection in a rostral–caudal direction adopted by the main author (R.R.), enables early identification of the trigeminal nerve and drainage of the cerebellopontine angle cistern with the consequent relaxation of the cerebellar parenchyma, which reduces excessive retraction and the risk of injury to the vii–viii complex. Zhang et al.8 recommend dissection in a caudal–rostral direction justified by the early mobilisation of the vertebral artery and to avoid sacrificing the petrosal vein complex of the cerebellopontine angle. In this regard, in the experience of the main author, this direction of dissection of the arachnoid requires excessive retraction which involves an unjustified risk of potentially disastrous nerve injury. Furthermore, in the experience of the main author, neurological deficit from sacrificing the petrosal vein complex has not been detected in any case operated.8 Another non-surgical treatment alternative is botulin toxin infiltration (Botox®), which has shown isolated favourable results. It is speculated that inhibiting and blocking neurotransmitters such as acetylcholine and glutamate in the nerve endings is responsible for the disappearance of muscular contractions, whereas blocking the activity of substance P alters the genesis of trigeminal neuralgia.10 Guyer et al.11 postulate the hypothesis of an analgesic effect achieved by toxin degradation products, with lower molecular weight. However, there is no molecular study that has identified these substances. The analgesic effect of botulinum toxin is known and accepted, but its main disadvantage is the temporariness of its effect. In this regard, Micheli et al.12 report a case of a 70-year-old patient with painful tic convulsive that responded favourably to botulin toxin infiltration in resolving hemifacial spasm and in significantly reducing the pain of neuralgia. However, the transient effect of the medical therapy resulted in a recurrence of symptoms and, therefore, retreatment every 12 weeks. The role of botulin toxin infiltration in the treatment of involuntary movements, which include hemifacial spasm, has been accepted, leaving no doubts as to the clinical benefit gained. However recurrence is the rule and repeat infiltration is necessary every 3.46 months on average, with 83% subjective improvement reported.13,14 Compared with the efficacy of microvascular decompression reported by Wang13 and Eboli et al.,15 with cure rates of 82–92%, and 84% permanence of clinical effect at 10 years, the surgical advantage is clear, although the medical alternative should always be considered for each individual case. Furthermore, the efficacy and mechanism of action of botulinum toxin in the treatment of pain syndromes, until recently the subject of constant debate, have been favoured by the growing scientific evidence regarding its analgesic effect.16–18 The debate is currently directed at the underlying mechanism of action. The single great disadvantage of this treatment is its short duration (<12 weeks) in pain control, even with great interstudy variability. Longer pain-free periods are achieved when the “trigger points” of the neuralgia are injected.17 The superiority of surgical treatment is evident in comparison, in definitive pain control reporting an average efficacy of 83.5% and 70% permanence of effect.19,20

Irrespective of the role of botulinum toxin in each separate manifestation, a beneficial effect has been highlighted for these simultaneous clinical symptoms through reports of isolated cases alone.12 However, no series has been published in the literature to date with a sufficient patient cohort to provide conclusions. It is a fact that the use of botulinum toxin is postulated as the best medical treatment for this rare condition. However, microvascular decompression surgery is the only treatment to have demonstrated beneficial effects long term or the permanent resolution of both symptoms.12

ConclusionsPainful tic convulsive is a rare disease with a frequency of <1% of the total number of rhizopathies due to vascular compression. Seventy-eight cases have been published in the literature to date, with the 2 described in this article. The aetiology most frequently associated with the genesis of this disease is vascular compression by an aberrant course of the vertebro-basilar complex. The incidence of compressive tumour disease is not negligible and in most cases corresponds to the presence of an epidermoid cyst of the cerebellopontine angle. The standard treatment for this rhizopathy of vascular compression is minimally invasive microvascular decompression using a microasterional approach with selective arachnoid dissection in the rostral–caudal direction. This technique has shown satisfactory outcomes in our experience; however, medical treatment with the injection of botulinum toxin is a less invasive alternative, with temporary relief of symptoms, and should be considered on assessing each individual case.

Ethical disclosuresProtection of human and animal subjectsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of dataThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols of their work center on the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Revuelta-Gutiérrez R, Velasco-Torres HS, Hidalgo LOV, Martínez-Anda JJ. Tic convulsivo doloroso: serie de casos y revisión de la literatura. Cir Cir. 2016;84:493–498.