Synchronous multiple primary malignancies in the female genital tract are infrequent. From 50 to 70% of them corresponds to synchronous cancers of the endometrium and ovary. To our knowledge, this is only the third case report in the international literature of three concurrent gynaecological cancers of epithelial origin. A case is presented, as well as a literature review due to the infrequency of its diagnosis and the lack of information on the subject.

Clinical caseA 49-year-old woman, with previous gynaecological history of ovarian endometriosis. She underwent a hysterectomy and bilateral oophorectomy, as she had been diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia with atypia. The final histopathology reported synchronous ovarian, Fallopian tube, and endometrial cancer. An extension study and complete surgical staging was performed, both being negative. She received adjuvant treatment of chemotherapy and radiotherapy. She is currently free of disease.

ConclusionsThe aetiology is uncertain. There is controversy relating to increased susceptibility of synchronous neoplasms to pelvic endometriosis and inherited genetic syndromes. Its diagnosis needs to differentiate them from metastatic disease. Additionally, they are problematical from a clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic, and prognostic point of view. The presentation of more cases of triple synchronous cancers is necessary for a complete adjuvant and surgical treatment.

El desarrollo sincrónico de múltiples tumores en el tracto genital femenino es infrecuente. Del 50% al 70% lo constituyen el grupo de neoplasias sincrónicas de endometrio y ovario. Para nuestro conocimiento este es el tercer caso de cáncer triple sincrónico ginecológico, de la bibliografía médica internacional. Nos proponemos exponer un caso de nuestra unidad y hacer una revisión de la bibliografía médica de esta entidad, dada la infrecuencia de su diagnóstico y la escasa información al respecto.

Caso clínicoMujer de 49 años de edad, con historia ginecológica de endometriosis ovárica. Se le realizó histerectomía y anexectomía bilateral, por diagnóstico de hiperplasia endometrial con atipias. La anatomía patológica definitiva informó de neoplasias sincrónicas de ovario, trompa y, endometrio. Se realizó estudio de extensión y se sometió a la paciente a cirugía de estadificación completa, siendo negativas. Se administró quimioterapia y radioterapia adyuvantes. Actualmente se encuentra libre de enfermedad.

ConclusionesLa etiología es incierta. Existe controversia acerca de una mayor predisposición de las neoplasias sincrónicas a la endometriosis pélvica y a los síndromes genéticos hereditarios. En su diagnóstico es necesario diferenciarlas de la enfermedad metastásica. Además plantean problemas desde el punto de vista clínico, diagnóstico, terapéutico y pronóstico. Es necesaria la presentación de más casos de neoplasias triple sincrónicas para un tratamiento quirúrgico y adyuvante completo.

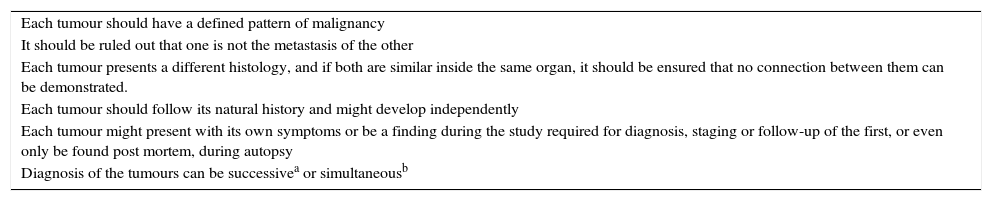

Malignancies which occur in one single subject, simultaneously or successively are termed multiple primary or synchronous tumours, provided they meet the outlined criteria1 (Table 1).

Diagnostic criteria of synchronous tumours.

| Each tumour should have a defined pattern of malignancy |

| It should be ruled out that one is not the metastasis of the other |

| Each tumour presents a different histology, and if both are similar inside the same organ, it should be ensured that no connection between them can be demonstrated. |

| Each tumour should follow its natural history and might develop independently |

| Each tumour might present with its own symptoms or be a finding during the study required for diagnosis, staging or follow-up of the first, or even only be found post mortem, during autopsy |

| Diagnosis of the tumours can be successivea or simultaneousb |

Synchronous tumours affect less than 1–2% of patients affected by cancers of the endometrium and ovary. The prevalence in epithelial cancer of the ovary corresponds to 10%, whereas in the case of adenocarcinoma of the endometrium it corresponds to 5%.2 Tubular adenocarcinomas have an incidence of 1%, most often being diagnosed by chance anatomopathologically following an operation. They generally occur in young, obese, nulliparous and premenopausal women, associated with hypoestrogenism.3 The average age of diagnosis is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.3,4 Some authors have described an association of double and triple synchronous tumours with hereditary genetic mutations, such as Lynch syndrome.5

Clinical caseA 49 year old woman, ex smoker, nulliparous, with a gynaecological history of ovarian endometriosis and a family history of paternal digestive tract tumour and a maternal aunt with breast cancer. An endometrial aspiration biopsy was performed for metrorrhagia. The anatomopathological diagnosis was endometrial hyperplasia with atypias. A scheduled hysterectomy was performed and bilateral adnexectomy. Final histopathology reported synchronous ovarian, right Fallopian tube, and endometrial cancer over extensive areas of ovarian endometriosis and myometrial adenomyosis. No pathological findings were reported in the ovary and contralateral Fallopian tube. The 3 malignancies were visualised without direct connection between them, with a different degree of infiltration. FIGO classification of each of the malignancies was adenocarcinoma of endometrium T1CG2, endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary T1A, and endometrioid adenocarcinoma of the Fallopian tube T1A. Immunohistochemistry revealed the same profile for the 3 malignancies: the presence of positive oestrogen and progesterone receptors, p53 negative and CK7 positive. Thoraco-abdominal computed tomography was requested, with no evidence of distant disease, and the patient underwent full staging surgery, including: peritoneal lavage, omentectomy, appendicectomy, pelvic and paraortic lymphadenectomy. Four and 5 lymph nodes were obtained in the right and left lymph node chains, respectively. At retroperitoneal level 2 lymph nodes were obtained, the anatomopathological study for both was negative. The patient received adjuvant chemotherapy treatment (taxol and cisplatin) and radiotherapy under oncological criteria, given the FIGO stage T1C G2 present in the endometrioid adenocarcinoma, with the objective of reducing the possibility of relapse (Fig. 1).

DiscussionThe aetiology of synchronous tumours is uncertain. Lauchlan proposed the extended müllerian system, which covers the epithelium from the ovarian surface, Fallopian tubes and uterus (neck and cervix) as a single morphological unit.6 Various authors a posteriori explained the possible presence of receptors in this müllerian system which would respond to carcinogens or hormonal factors.4,7 this would explain synchronous tumours of a similar aetiology, but not those of a different aetiology.

The patients are classically young, obese, nulliparous and premenopausal,3 like the patient presented. There is controversy in medical literature regarding the association of a greater predisposition for synchronous malignancies with pelvic endometriosis.2,8,9 Some authors argue the use of combined hormonal contraception in patients with endometriosis as a chemopreventive factor against gynaecological synchronous malignancies.10

Synchronous carcinomas of the endometrium and ovary pose various problems from a clinical, diagnostic, therapeutic and prognostic perspective; therefore a differential diagnosis with metastatic disease is of crucial importance. In favour of the presence of ovarian metastasis are: the small size of the ovarian lesion, bilateral involvement, pattern of multinodular growth, the presence of associated superficial implants, and prominent vascular lymphatic embolisation of the stroma of the ovary.1,11 Other methods which help us to differentiate synchronous tumours from metastatic tumours are: molecular studies, the presence of micro-satellites, flow cytometry or PTEN oncogene mutation12; although as yet there is no consensus amongst anatomopathologists as to their usefulness.13

Immunohistochemistry is of little value in differentiation, as both endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary and the uterus, primary and metastatic, have similar immunophenotypical characteristics.9

According to Dragoumis et al.14 in their review, treatment should be appropriate for both tumours, taking into consideration that the treatment of one tumour can lead to incomplete treatment of the other. Generally treatment with adjuvant chemotherapy with or without association with radiotherapy is the most used.

Synchronous tumours of the ovary and endometrium are tumours with a good prognosis, especially in the early stages. Survival at 5 years is 85.9% and at 10 years is 80.3%.4,15,16 Survival depends on the FIGO stage, the tumour's histology, and the association with adjuvant treatment.5,15 Relapse varies according to the different authors at around 15.1%4,15 or 34%5 at 5 years.

From an anatomopathological perspective these are tumours of difficult differential diagnosis with metastasis, with different therapeutic and prognostic implications. Studies which enable a differential diagnosis of both are necessary. In general, these are tumours with a good prognosis, as most are diagnosed in early stages and endometrioid histology predominates.

ConclusionsWe have only found 2 cases in medical literature on triple synchronous tumours of the ovary, endometrium and Fallopian tube, and therefore we consider that publishing this case is highly relevant. We do not know whether the prognosis and treatment are comparable to synchronous tumours of the ovary and endometrium, or conversely, whether they are more aggressive.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Gutiérrez-Palomino L, Romo-de los Reyes JM, Pareja-Megía MJ, García-Mejido JA. Tumores triple sincrónicos ginecológicos. Reporte de un caso. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2016;84:69–72.