Focal photocoagulation interrupts vascular leakage in diabetic macular oedema, and allows the retinal pigment epithelium to withdraw fluid that thickens the retina; this mechanism could be enhanced by dorzolamide, a topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor.

ObjectiveTo determine the efficacy of dorzolamide compared to placebo, in reducing retinal thickness after focal photocoagulation in eyes with diabetic macular oedema.

Material and methodsExperimental, comparative, prospective, longitudinal, double blind study in diabetics with focal macular oedema treated with photocoagulation. Treated eyes were randomly assigned three weeks after the procedure to receive dorzolamide (group 1) or placebo (group 2), three times daily for three weeks. Means of visual acuity, centre point thickness and macular volume were compared 3 and 6 weeks after photocoagulation within groups (Wilcoxon t) and between groups (Mann-Whitney-U).

ResultsSixty-nine eyes form patients aged 58.3 ± 8.3 years; 37 were assigned to group 1 and 42 to group 2. Mean centre point thickness changed from 178.4 ± 34μm to 170 ± 29.1μm in group 1 (p = 0.04), and from 179.2 ± 22.4μm to 178.6 ± 20.8μm in group 2 (p = 0.07); mean macular volume changed from 7.63 ± 0.52mm3 to 7.50 ± 0.50mm3 in group 1 (p = 0.002) and from 7.82 ± 0.43mm3 to 7.76 ± 0.42mm3 in group 2 (p = 0.013).

ConclusionsThe efficacy of dorzolamide was higher than that of placebo in reducing retinal thickness after focal photocoagulation in diabetics with macular oedema.

La fotocoagulación focal interrumpe la fuga vascular en el edema macular diabético, con lo cual el epitelio pigmentario retiniano puede retirar el líquido que engrosa la retina; este mecanismo podría facilitarse con dorzolamida, un inhibidor tópico de la anhidrasa carbónica.

ObjetivoDeterminar la eficacia de dorzolamida comparada contra placebo, para reducir el grosor retiniano después de la fotocoagulación focal, en el edema macular diabético.

Material y métodosEstudio experimental, comparativo, prospectivo, longitudinal, doble ciego, en diabéticos con edema macular focal tratados con fotocoagulación, aleatorizados 3 semanas después del procedimiento para recibir dorzolamida (grupo 1) o placebo (grupo 2). Se compararon los promedios de agudeza visual, grosor del punto central y volumen macular 3 y 6 semanas después de la fotocoagulación en cada grupo (t de Wilcoxon) y entre grupos (U de Mann-Whitney).

ResultadosSetenta y nueve ojos de pacientes con una edad ± desviación estándar de 58.3 ± 8.3 años; se asignaron 37 al grupo 1 y 42 al grupo 2. El grosor del punto central cambió de 178.4 ± 34μm a 170 ± 29.1μm en el grupo 1 (p = 0.04), y de 179.2 ± 22.4μm a 178.6 ± 20.8μm en el 2 (p = 0.7); el volumen macular cambió de 7.63 ± 0.52mm3 a 7.50 ± 0.50mm3 en el grupo 1 (p = 0.002) y de 7.82 ± 0.43mm3 a 7.76 ± 0.42mm3 en el grupo 2 (p = 0.013).

ConclusionesLa dorzolamida aplicada durante 3 semanas fue más eficaz que el placebo para reducir el grosor retiniano después de la fotocoagulación focal en diabéticos con edema macular.

Macular oedema is the most frequent cause of vision loss in diabetic retinopathy; when clinically significant, it involves risk of moderate vision loss (doubling of visual angle, loss of 3 lines on an eye chart)1, present in 6.8% of diabetic patients2.

In macular oedema, the thickness of the retina in the macula increases due to leakage of intravascular fluid coming from microaneurysms (focal leakage) or dilated capillaries next to a microvascular occlusion area (diffuse oedema). The thickening of the macula distorts photoreceptors, which causes vision loss3.

One treatment for macular oedema is photocoagulation, which reduces the incidence of moderate vision loss from 33 to 13% in a 3-year period1. In focal oedema, photocoagulation, the treatment of choice4, seals the leaking microaneurysms, and intraretinal fluid may retract towards adjacent capillaries and the choroid.

Under normal conditions, the retinal pigment epithelium transports water from the vitreous humour to the choroid, maintaining normal retinal thickness5. When the leakage of a microaneurysm exceeds the transport capacity of the pigment epithelium, the macula thickens; once the leakage ceases, the pigment epithelium progressively withdraws intraretinal fluid, which decreases the thickness of the macula.

The pigment epithelium of the retina withdraws the fluid through a Na/K+ ATPase located in the basolateral membrane, the activity of which is facilitated when the concentration of H2CO3 in the subretinal space increases. High levels of CO2 in the subretinal space reduce adhesion among the pigment epithelium and the neurosensory retina, and allows for the accumulation of intraretinal and subretinal fluid6; this condition is more common when there are high concentrations of carbonic anhydrases, as in the case of diabetes7.

Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors have been used orally for more than 50 years to reduce the formation of aqueous humour and to lower intraocular pressure, but they cause systemic adverse reactions; dorzolamide is a topical inhibitor of carbonic anhydrases, efficient as an ocular hypotensor, and usually well tolerated8, reaching peak concentrations of 24.0 μg/g in the cornea, 7.8 μg/ml in aqueous humour and 27.0 μg/g in the ciliary body. In the retina, it reaches a maximum concentration of 5.29 μg/g, which would explain its effect on intraretinal fluid9.

Dorzolamide has been efficient in treating macular oedema present in diseases such as retinitis pigmentosa10, choroideremia11 and retinoschisis12. The mechanism proposed for this response is the inhibition of carbonic anhydrases of the pigment epithelium, which favours the activity of Na/K+ ATPase and increases the transport of fluid towards the choroid.

The increase in the transport of fluid through the retinal pigment epithelium may facilitate the resolution of retinal thickening in eyes with diabetic macular oedema, once the capillary leak site is closed; this intervention would shorten the time of resolution of the thickening and probably limit visual dysfunction.

A study was carried out to determine the efficacy of dorzolamide, as compared to placebo, to reduce retinal thickness after focal photocoagulation, in eyes with diabetic macular oedema.

Material and methodsAn experimental, comparative, prospective, longitudinal and double-blind study was carried out in diabetic patients with clinically significant macular oedema from a general hospital in Mexico City, from February 1 to December 14, 2012. The study was authorized by the Research and Research Ethics commissions of the institution where it was carried out.

It included type 2 diabetic patients, of any gender and age, with any degree of diabetic retinopathy, presenting clinically significant macular oedema with focal angiographic leakage, to measure visual acuity and obtain a 6mm fast macular map of proper quality. Patients excluded from the study were those with other retinal diseases decreasing visual acuity, intraocular swelling, poor foveal fixation, patients who would develop opacity of mean after the first measurement, abandoned the treatment, failed to attend the third measurement, and those with fast macular map with measurement errors.

For all patients, measurement was made of visual acuity corrected with refraction, in decimal equivalent, and of macular thickness through a fast macular map with the Stratus optical coherence tomography equipment (Carl Zeiss, Dublin, US); measurements were carried out before treatment, and at 3 weeks and 6 weeks post-treatment. Only one retina specialist applied focal photocoagulation, according to the guidelines in the “Early treatment diabetic retinopathy study”.

Patients were invited to participate in the study 3 weeks after having received the focal photocoagulation. After patients were explained about the informed consent form and signed it, those who accepted to participate in the study were randomly assigned to one of 2 groups: 1 (dorzolamide 2%) or 2 (Polyvinyl alcohol).

Dependent variables were the thickness of the central point, measured in microns, and the macular volume measured in mm3, according to the automatic calculation of the fast macular map; the independent variable was the topical drug received, defined as the ophthalmological solution applied in the conjunctival cul-de-sac, every 8hours from 3 to 6 weeks after photocoagulation. Visual acuity was considered a secondary variable, defined as that found under subjective refraction and measured in decimal equivalent.

Fast macular maps were measured through the following standardised procedure: pharmacological mydriasis of at least 6mm (tropicamide 0.8% and phenilephrine 5%), identification of the retina plane through acoustic alert, optimisation of the z-axis and polarisation; the study was taken using flash. To verify map centring, the thickness of the central field was compared to the thickness of the central point; it was ensured that the last value was lower than that of the first and that the thinner area of the retina was within the central circle; all maps were obtained by only one investigator, other than the investigator who applied the treatment.

Measurement errors were considered to be: any deviation from the tomography line with optical coherence with respect to the real limit of the retina, a standard deviation relation of the thickness of the central point/thickness of the central point > 0.1 and at a signal intensity lower than 4.

The averages of the central point thickness and the macular volume were compared 3 and 6 weeks after photocoagulation among groups through the Mann-Whitney U-test; for each group the thickness of the central point and the macular volume at 3 weeks were compared to that at 6 weeks through Wilcoxon T-test. In addition, for each group, the averages of thickness of the central point and macular volume were compared prior to photocoagulation through the Friedman test after 3 and 6 weeks.

Values with p < 0.05 were considered significant; the information was stored and analysed with the SPSS software for Windows, version 20.

Results79 eyes of 63 patients were assessed, aged 41 to 73 years (average ± standard deviation [SD] 58.3 ± 8.3 years); 45 eyes (57%) were of female patients. The average ± SD of the time of evolution of the diabetes was 14.8 ± 7.1 years, fasting blood sugar levels 185.2 ± 83.7 mg/dl and glycosylated haemoglobin 8.88 ± 2.4%. Thirty eyes belonged to patients treated with insulin (38%) and 41 (51.9%) to patients with high blood pressure.

Visual acuity prior to photocoagulation reached an average of 0.54 ± 0.27; the degree of diabetic retinopathy was mild non-proliferative in 4 eyes (5.1%), moderate non-proliferative in 41 (51.8%), severe non-proliferative in 4 (5.1%) and proliferative in 30 (38%). The average ± SD of the thickness of the central point was 175.3 ± 27.3 μm and the macular volume 7.81 ± 0.57mm3; 3 weeks after the photocoagulation, the average visual acuity was 0.59 ± 0.26 (p = 0.03), the thickness of the central point average was 178.8 ± 28.2 (p = 0.09) and the macular volume average was 7.73 ± 0.48mm3 (p = 0.02). Thirty-seven eyes were assigned to group 1 and 42 to group 2.

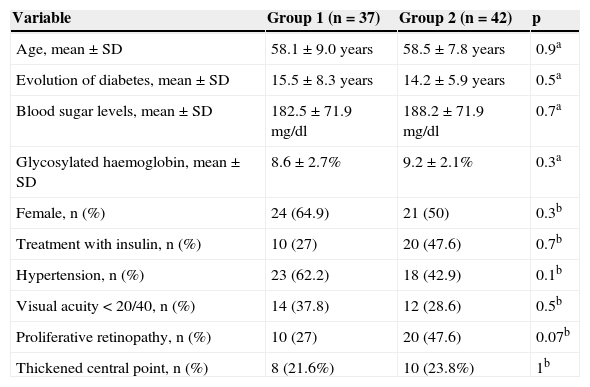

Systemic and ocular variables did not differ among groups 3 weeks after photocoagulation (Table 1).

Comparison of anatomical and ocular variables between groups, 3 weeks after photocoagulation.

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 37) | Group 2 (n = 42) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± SD | 58.1 ± 9.0 years | 58.5 ± 7.8 years | 0.9a |

| Evolution of diabetes, mean ± SD | 15.5 ± 8.3 years | 14.2 ± 5.9 years | 0.5a |

| Blood sugar levels, mean ± SD | 182.5 ± 71.9 mg/dl | 188.2 ± 71.9 mg/dl | 0.7a |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin, mean ± SD | 8.6 ± 2.7% | 9.2 ± 2.1% | 0.3a |

| Female, n (%) | 24 (64.9) | 21 (50) | 0.3b |

| Treatment with insulin, n (%) | 10 (27) | 20 (47.6) | 0.7b |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 23 (62.2) | 18 (42.9) | 0.1b |

| Visual acuity < 20/40, n (%) | 14 (37.8) | 12 (28.6) | 0.5b |

| Proliferative retinopathy, n (%) | 10 (27) | 20 (47.6) | 0.07b |

| Thickened central point, n (%) | 8 (21.6%) | 10 (23.8%) | 1b |

SD: standard deviation

a Mann-Whitney U-test.

b X2.

Before receiving the topical drug, the average of visual acuity was 0.55 ± 0.27, the central point thickness average was 178.4 ± 34 μm, and the macular volume average was 7.63 ± 0.52mm3. After implementing the topical drug, the average of visual acuity was 0.54 ± 0.28 (p = 0.7), the central point thickness average was 170 ± 29.1 μm (p = 0.04) and the macular volume average was 7.50 ± 0.50mm3 (p = 0.002).

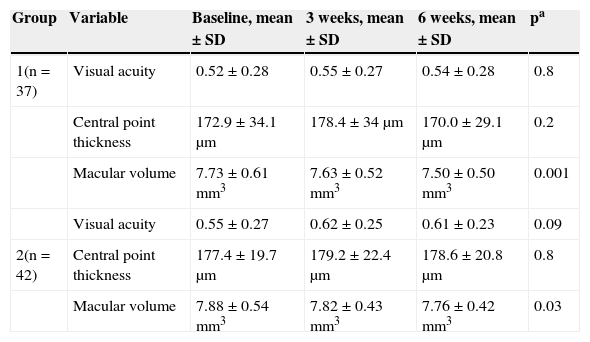

The averages for visual acuity and central point thickness did not vary significantly prior to photocoagulation, or 3 and 6 weeks after; the macular volume average at 6 weeks was significantly lower than that found prior to photocoagulation and 3 weeks after (Table 2).

Comparison of the average of variables in each group.

| Group | Variable | Baseline, mean ± SD | 3 weeks, mean ± SD | 6 weeks, mean ± SD | pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1(n = 37) | Visual acuity | 0.52 ± 0.28 | 0.55 ± 0.27 | 0.54 ± 0.28 | 0.8 |

| Central point thickness | 172.9 ± 34.1 μm | 178.4 ± 34 μm | 170.0 ± 29.1 μm | 0.2 | |

| Macular volume | 7.73 ± 0.61mm3 | 7.63 ± 0.52mm3 | 7.50 ± 0.50mm3 | 0.001 | |

| Visual acuity | 0.55 ± 0.27 | 0.62 ± 0.25 | 0.61 ± 0.23 | 0.09 | |

| 2(n = 42) | Central point thickness | 177.4 ± 19.7 μm | 179.2 ± 22.4 μm | 178.6 ± 20.8 μm | 0.8 |

| Macular volume | 7.88 ± 0.54mm3 | 7.82 ± 0.43mm3 | 7.76 ± 0.42mm3 | 0.03 |

SD: standard deviation.

a Friedman.

Prior to receiving the topical drug, the average of visual acuity was 0.62 ± 0.25, the central point thickness average was 179.2 ± 22.4 μm and the macular volume average was 7.82 ± 0.43mm3. After implementing the topical drug, the average of visual acuity was 0.61 ± 0.23 (p = 0.05), the central point thickness average was 178.6 ± 20.8 μm (p = 0.7) and the macular volume average was 7.76 ± 0.42mm3 (p = 0.013).

The averages for visual acuity and central point thickness did not vary significantly prior to photocoagulation, or 3 and 6 weeks after; the macular volume average at 6 weeks was significantly lower than that found prior to photocoagulation and 3 weeks after (Table 2).

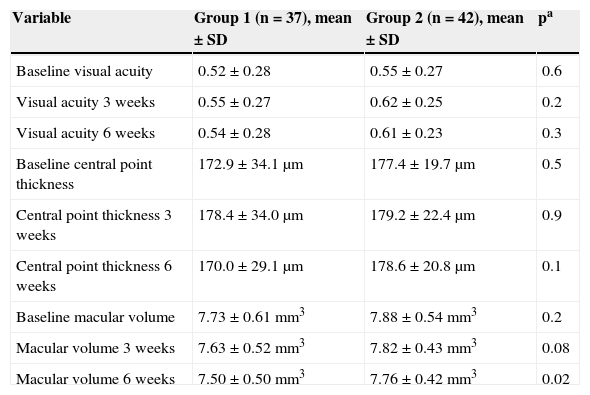

The comparison of averages of the variables among groups is presented in Table 3. The reduction of macular volume led to a significantly lower average in group 1, 6 weeks after applying photocoagulation.

Comparison of the average of variables between groups.

| Variable | Group 1 (n = 37), mean ± SD | Group 2 (n = 42), mean ± SD | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline visual acuity | 0.52 ± 0.28 | 0.55 ± 0.27 | 0.6 |

| Visual acuity 3 weeks | 0.55 ± 0.27 | 0.62 ± 0.25 | 0.2 |

| Visual acuity 6 weeks | 0.54 ± 0.28 | 0.61 ± 0.23 | 0.3 |

| Baseline central point thickness | 172.9 ± 34.1 μm | 177.4 ± 19.7 μm | 0.5 |

| Central point thickness 3 weeks | 178.4 ± 34.0 μm | 179.2 ± 22.4 μm | 0.9 |

| Central point thickness 6 weeks | 170.0 ± 29.1 μm | 178.6 ± 20.8 μm | 0.1 |

| Baseline macular volume | 7.73 ± 0.61mm3 | 7.88 ± 0.54mm3 | 0.2 |

| Macular volume 3 weeks | 7.63 ± 0.52mm3 | 7.82 ± 0.43mm3 | 0.08 |

| Macular volume 6 weeks | 7.50 ± 0.50mm3 | 7.76 ± 0.42mm3 | 0.02 |

SD: standard deviation

a Mann-Whitney U-test.

Eyes receiving dorzolamide 3 weeks after focal photocoagulation presented a significant reduction in central point thickness, which was non-existent in the eyes of those who received placebo. Although the macular volume decreased significantly in both groups, the average found 6 weeks after photocoagulation in eyes receiving dorzolamide was statistically lower than in the eyes receiving placebo.

When the retina is thickened due to abnormal leakage, the amount of leaked fluid is lower than that accumulated in a cavity, as in retinoschisis; dorzolamide has been efficient in eliminating intraretinal fluid in this disease, and therefore it was expected to favour a reduction of retinal thickness higher than the lubricant after photocoagulation.

Systemic carbonic anhydrases inhibitors have been used since 1988 to treat the macular oedema caused by several diseases13, although its use was restricted due to its systemic adverse events. These decrease with the administration of topical inhibitors, which are used as second line drugs to treat glaucoma14 and their efficacy to treat cystoid macular oedema in retinitis pigmentosa is similar to that of acetazolamide15.

It has been reported that the response to treatment with carbonic anhydrase inhibitors is better in macular oedema caused by pigment epithelium alterations than that presented in vascular diseases, such as diabetic retinopathy or venous occlusions16. Diabetic macular oedema with focal leakage does not affect the pigment epithelium and the amount of fluid leaking towards the retina exceeds the capacity of the latter to withdraw it; by closing microaneurysms with photocoagulation, topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitors may increase the transport of fluid towards the choroid, which does not occur when they are administered as the sole treatment.

After photocoagulation, fluid is also withdrawn through competent adjacent capillaries, the capacity of which increases through vasodilation. The procedure promotes this effect by increasing genic expression of angiotensin II receptor type 2 in the retina17. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors also induce retinal venous vasodilation18, which is higher with the administration of dorzolamide than with the administration of acetazolamide19.

Focal photocoagulation induces swelling, which may increase central point thickness; this change may be found even 3 weeks after the procedure20, and therefore, the administration of dorzolamide in this study was initiated after this period. In uveitis-induced cystoid macular oedema, carbonic anhydrases inhibitors reduce intraretinal fluid when there is no active swelling21, but when there is, they do not improve vision, which is why its use has decreased22.

The reduction of the thickening did not change visual acuity significantly in any group, but this was a secondary variable that shall have to be evaluated once the efficacy of dorzolamide to reduce retinal thickness has been demonstrated. In eyes with retinitis pigmentosa, Ikeda et al.10 reported that the resolution of thickening obtained with dorzolamide did not improve visual acuity, but it did improve retinal sensitivity; Genead and Fishman identified visual improvement in 31% of their patients with Usher syndrome treated with dorzolamide23.

In non-degenerative origin diseases, such as central serous choroidopathy, treatment with brinzolamide (another topical carbonic anhydrase inhibitor) showed a tendency towards visual improvement24.

To evaluate the efficacy of dorzolamide to improve visual function after focal photocoagulation and the best moment to administer it will require a specific design considering other variables associated with visual improvement.

ConclusionsDorzolamide applied for 3 weeks was more efficient than the placebo to reduce retinal thickness after focal photocoagulation in diabetics with macular oedema.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.