Clinical practice guidelines are tools that have been able to streamline decisions made in health issues and to decrease the gap between clinical action and scientific evidence.

ObjectiveThe objective of the study is to share the experience in the development and to update the guidelines by the Sistema Nacional de Salud de Mexico.

Material and methodsThe methodology in the development of the guidelines consists of 5 phases: prioritisation, establishment of work groups, development by adoption of international guidelines of de novo, validation and integration in the Master catalogue of clinical practice guidelines for its dissemination.

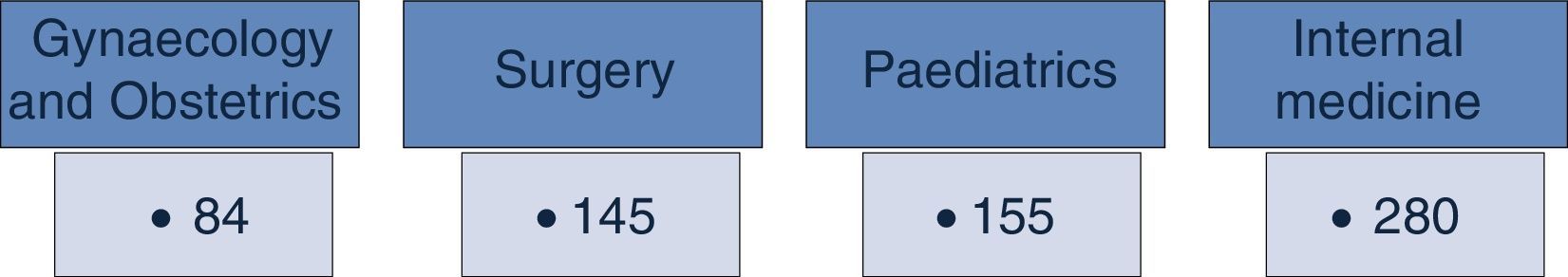

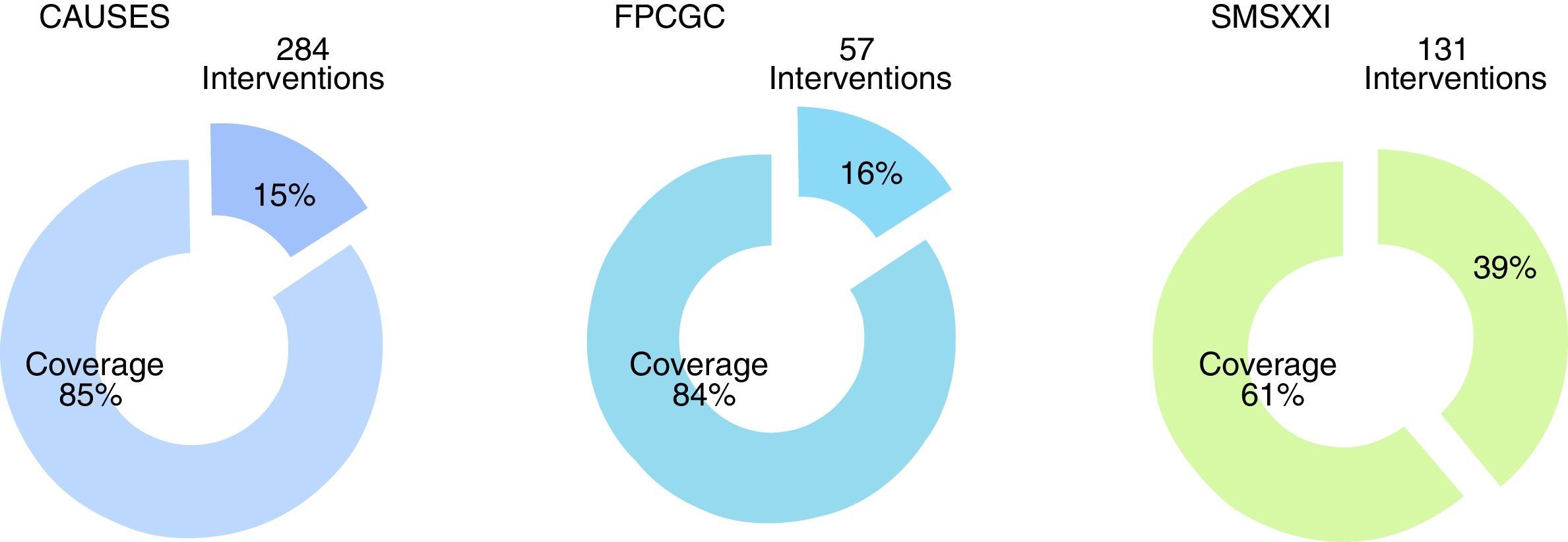

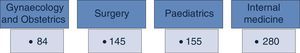

ResultsThe Master catalogue of clinical practice guidelines contains 664 guidelines, distributed in 42% Internal Medicine, 22% Surgery, 24% Paediatrics and 12% Gynaecology. From the total of guidelines coverage is granted at an 85% of the Universal catalogue of health services, an 84% of the Catastrophic expenses protection fund and a 61% of the XXI Century Medical Insurance of the National Commission of Social Protection in Health.

DiscussionThe result is the sum of a great effort of coordination and cooperation between the institutions of the Sistema Nacional de Salud, political wills and a commitment of 3477 health professionals that participate in guidelines’ development and update.

ConclusionMaster catalogue guidelines’ integration, diffusion and implantation improve quality of attention and security of the users of the Sistema Nacional de Salud.

Las guías de práctica clínica son herramientas que han demostrado hacer más racionales las decisiones en salud y disminuir la brecha entre la acción clínica y la evidencia científica.

ObjetivoEl estudio tiene como objetivo compartir la experiencia en el desarrollo y actualización de guías por el Sistema Nacional de Salud de México.

Material y métodosLa metodología en el desarrollo de guías consta de 5 fases: priorización, conformación de grupos de trabajo, desarrollo por adopción de guías internacionales o de novo, validación e integración en el Catálogo maestro de guías de práctica clínica para su difusión.

ResultadosEl Catálogo maestro de guías de práctica clínica aloja 664 guías, distribuidas de la siguiente forma: 42% son de Medicina Interna, 22% de Cirugía, 24% de Pediatría y el 12% de Ginecología y Obstetricia. Del total de las guías, se da cobertura al 85% del Catálogo universal de servicios de salud, al 84% del Fondo de protección contra gastos catastróficos y al 61% del Seguro Médico Siglo XXI de la Comisión Nacional de Protección Social en Salud.

DiscusiónEl resultado es la suma de un esfuerzo de coordinación y cooperación de las instituciones del Sistema Nacional de Salud, de las voluntades políticas y del compromiso de 3,477 profesionales de la salud que participan en el desarrollo y actualización de las guías.

ConclusionesLa integración, difusión e implantación de las guías del Catálogo maestro mejora la calidad de la atención y seguridad de los usuarios del Sistema Nacional de Salud.

Clinical practice guidelines are tools which have been able to streamline decisions made in health and to decrease the gap between clinical action and scientific evidence.1–3 Their implementation reduces bias in decisions made by healthcare professionals and helps to improve the quality of that healthcare. Both the patient's and the professional's role is enhanced during care, and effective communication can be made between the different decision makers.4–7 they also help to increase efficiency and in contention of health costs.8,9

The globally accepted concept of clinical practice guidelines is the one proposed by the US Institute of Medicine: “a set of recommendations, developed systematically to help health professionals and patients take decisions regarding the most appropriate medical attention, selecting the most appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic opinions to approach a health problem or specific clinical condition”. The US Institute of Medicine recently added: “based on systematic reviews and risk/benefit assessment of health interventions”.10,11

The use of clinical practice guidelines creates a challenge for the health system and it is therefore essential to identify usage barriers and facilitators with regards to the recommendation construction procedure, quality of the guidelines and their relationship with all the social, legal and ethical aspects which would be involved in daily practice.12,13

In Mexico, clinical guidelines have been published by different medical associations or health institutions, including the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social.14–17 However, until 2007, no standard model existed for their presentation. Methodology and processes of creation were diverse and were not often accompanied by validation procedures. In the face of this scenario, a frequent result was a multiplicity of efforts and uncoordinated products which resulted in clinical practice guidelines of varying quality, based more on the consensus of experts rather than rigorous scientific evidence.18

The Programa Sectorial de Salud 2007–2012 (PROSESA) defines its third strategy of “positioning quality on the permanent agenda of the Sistema Nacional de Salud” and as a line of action is committed to promoting the use of clinical practice guidelines and medical care protocols. Similarly, the fourth strategy of PROSESA 2007–2012 seeks to “develop planning, management and assessment tools for the Sistema Nacional de Salud”, and is committed to the “integration of the master catalogue of clinical practice guidelines”.19

Under this context the “Specific action programme for the development of clinical practice guidelines 2007–2012” was developed, the purpose of which was to establish a national reference to promote clinical and managerial decision-making based on recommendations sustained by the best available evidence, with the firm aim to reduce the use of unnecessary or ineffective interventions and facilitate patient treatment to the maximum benefit, minimum risk and at an acceptable cost.20

The internal regulation of the Ministry of Health, article 41, authorises the Centro Nacional de Excelencia Tecnológica en Salud (CENETEC-Salud) to establish jointly with the Sistema Nacional de Salud Institutions sufficient methodology to draw up clinical practice guidelines, promote and coordinate their integration and disseminate them in order to guide the decision-making of health service professionals and users.21

The first agreements resulted from a workshop of consensus celebrated in July 2007, with participation from the National Health System's public institutions. The agreement which led to the creation of the National Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines in 2008 was subsequently derived from the commitment set out in PROSESA 2007–2012, and from the political will of the people involved in the events. This body acts as an advisory service to the Ministry of Health and its purpose is to unify the criteria of prioritisation, development, adaptation, updating, dissemination, usage and assessment of the clinical practice guidelines in the National Health Institutions. The National Committee for Clinical Practice Guidelines comprises Ministry of Health representatives, the heads of different health institutions, chairpersons of the Academia Nacional de Medicina de México and the Academia Mexicana de Ciencias, and also representatives from previously accepted civil associations.22

The cooperation between institutions for the development of clinical practice guidelines is the responsibility of the Strategic Work Group made up of representatives from the Sistema Nacional de Salud whose functions involve working with clinical practice guidelines. This work group creates the agreements which are subsequently submitted for analysis and, if appropriate, for approval by the National Committee of Clinical Practice Guidelines. The Strategic Work Group also communicates the agreements to the operational work groups, which formulate the clinical practice guidelines.

The aim of this article is to inform the medical community of the work and effort involved by the institutions of the Sistema Nacional de Salud de Mexico for the development of clinical practice guidelines whose purpose is the improvement in health care quality and the safety of our patients, in addition to optimal planning and resource management.

Material and methodsThe public institutions of the Sistema Nacional de Salud have reached an agreement regarding the methodology for the development of clinical practice guidelines sustained by the best available scientific evidence which consists of the following phases (Fig. 1).

Priority will be given to the development of clinical practice guidelines in the following order of diseases or interventions:

- (a)

Diseases and interventions listed in the Universal Catalogue of Health Services which has the highest incidence and prevalence in the country, particularly those relating to hospitalisation, emergencies and general surgery, and those highlighted by the National Commission of Social Health Protection in its capacity as the financer of said services.

- (b)

Diseases or interventions which are generally not high in incidence but which due to their characteristics, represent a high expenditure for the family or the patient and are listed by the National Commission of Social Health Protection in their Catastrophic expenses protection fund.

- (c)

Diseases which affect children under 5, proposed by the National Commission of Social Protection in Health, and under the XXI Century Medical Insurance programme cover.

- (d)

Condition or illness associated with a high frequency of sequelae or adverse events, and which form part of the governmental programmes, and institutional or national priorities.

- (e)

Groups related to diagnostics and groups related to outpatient health care.

Once the Strategic Work Group proposes which clinical practice guidelines should be developed, it presents them to the National Committee of Clinical practice guidelines in compliance with the annual working plan, coordinated by CENETEC-Salud.

Formation of work groups for developing the guidelinesOnce the guidelines have been defined, groups of professional health experts in the diseases or interventions to be developed are formed and accept their responsibility to draw up the corresponding clinical practice guidelines, working altruistically and under no conflict of interest. The groups of experts meet together to receive training in theoretical and practical methodology which consists of 3 main focal points: the development process of a clinical practice guideline, the structuring of clinical questions and a systemised process of information search in specialised areas.

Development of the clinical practice guidelinesThe process of development of a clinical practice guideline is completed through the adoption and adaptation of already existing guidelines or new ones, depending on the existing documents and the need for response to the questions established in the guidelines.

- (a)

Adoption and adaptation. The process of adoption and adaptation of clinical practice guidelines is a strategy which helps to reduce delivery times and duplicity of efforts, using a uniform, simple and systematic methodology for this proposal. The process consists of searching for clinical practice guidelines which have already been published, either nationally or internationally and which offer a response to the goals and objectives of the proposed theme. These guidelines are then submitted for assessment through the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation (AGREE II) system and if they are of an acceptable quality, they are adopted and adapted to the national context.

- (b)

De novo development. If there are no reference guidelines, the group of experts develops the guideline from scratch using a systematic search of available literature and interpretation of events, related with the previously defined population through critical analysis of systematic reviews, meta-analysis, randomised clinical trials, and observational studies. When evidence is limited or nonexistent, the recommendations issued include a consensus of option from the group of experts.

The construction of clinical questions is a starting point and key element in the development of the guideline, with priority given to controversies between clinical practice guidelines, risks and factors which have direct impact on morbidity, diagnosis and treatment. The structuring of the clinical questions is through the PICO system (patient, intervention, comparison, and outcome) and with consideration of the context in which the recommendations will be applied.23

Once the clinical questions have been formulated, the protocol of systematically searching for information in specialised areas is systematically introduced. The design and use of the information search protocol is aimed at systematising the search process, to release relevant information which is independent of selection bias. The protocol must be flexible, reproducible and validated.24

The creation of a search protocol essentially necessitates development of the title of the guideline, key words and terms related to the subject, the focus of the guidelines (prevention, diagnostics, treatment, etc.), and the types of documents sought. Initially the latter would be clinical practice guidelines or if they are unavailable, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, randomised clinical trials, or observational studies.

The time estimated for the development of a clinical practice guideline is between 12 to 18 months. During this time both authors and guide coordinators will communicate by telephone and four face-to-face follow-up meetings are arranged to focus all the time and efforts of all participants. These last one week each, until the guideline has been fully integrated.

Validation of the guidelinesThe first validation is the reproduction of the search protocol by a librarian or similar professional. This search protocol must be precise (concordance between that searched and that found), exhaustive (provide the maximum results possible about the specific search), be available in the data base and free from selection bias.

Once complete, the guideline is sent to a group of independent specialists for its validation, i.e. to confirm that evidence and recommendations are in keeping with clinical practice guidelines. If the validators have comments, these are returned to the group of experts with scientific evidence to support them.

Integration into the master catalogue of clinical practice guidelinesThe National Committee of Clinical practice guidelines meets every 3 months in an ordinary session and this is when the guidelines which have been validated up until this time are integrated. When they are fully approved, they form part of the Master Catalogue of clinical practice guidelines for publication and dissemination.

ResultsThe National Committee of Clinical practice guidelines establishes a common agreement regarding the annual work, which serves as the general directive for confirmation of policies, criteria and strategies for the development of clinical practice guidelines.

The methodology agreed by the Institutions of the National Health System for the adoption and adaption of guides for the creation of a search protocol, has served as the base for the successful development of clinical practice guidelines.

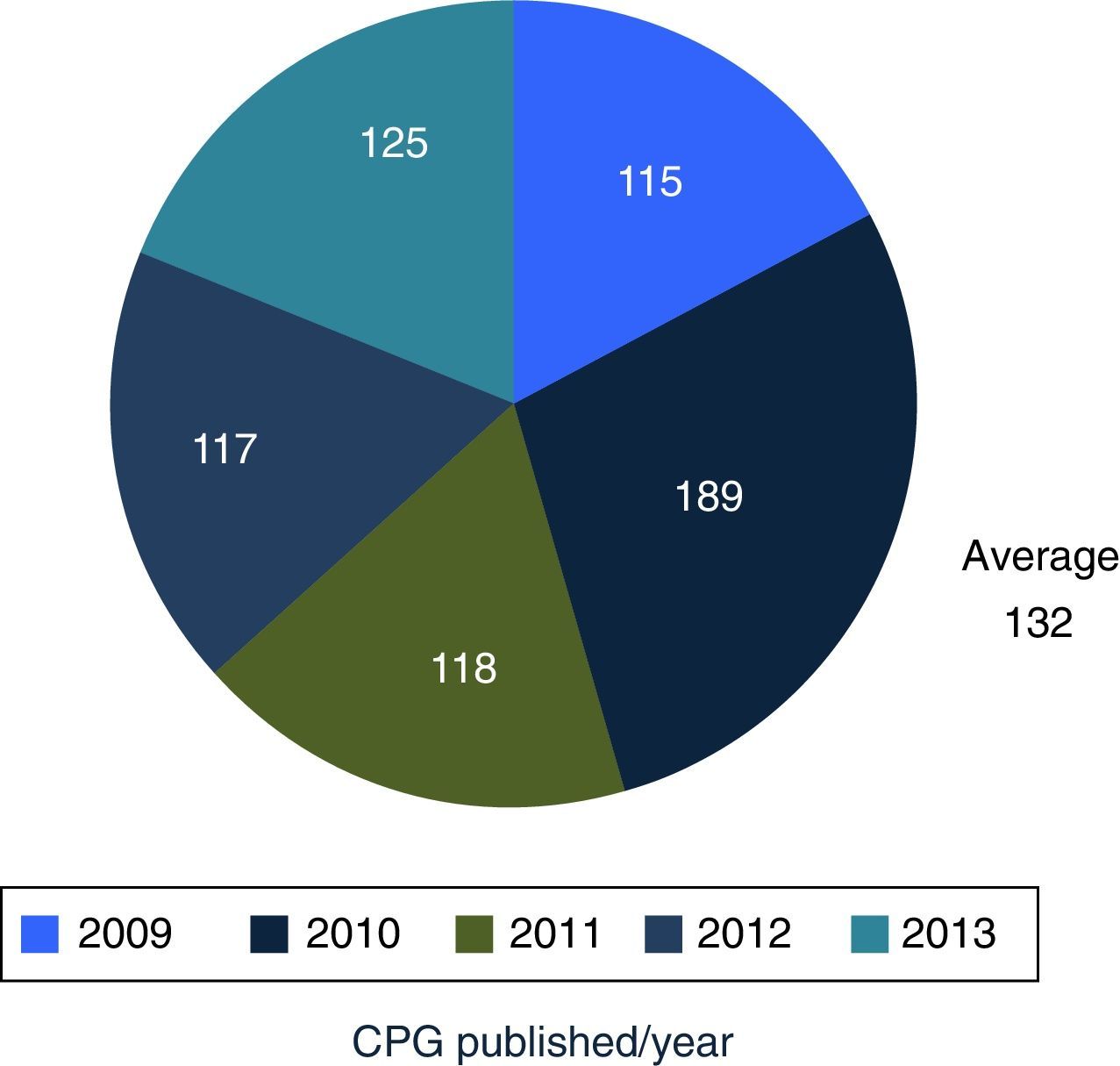

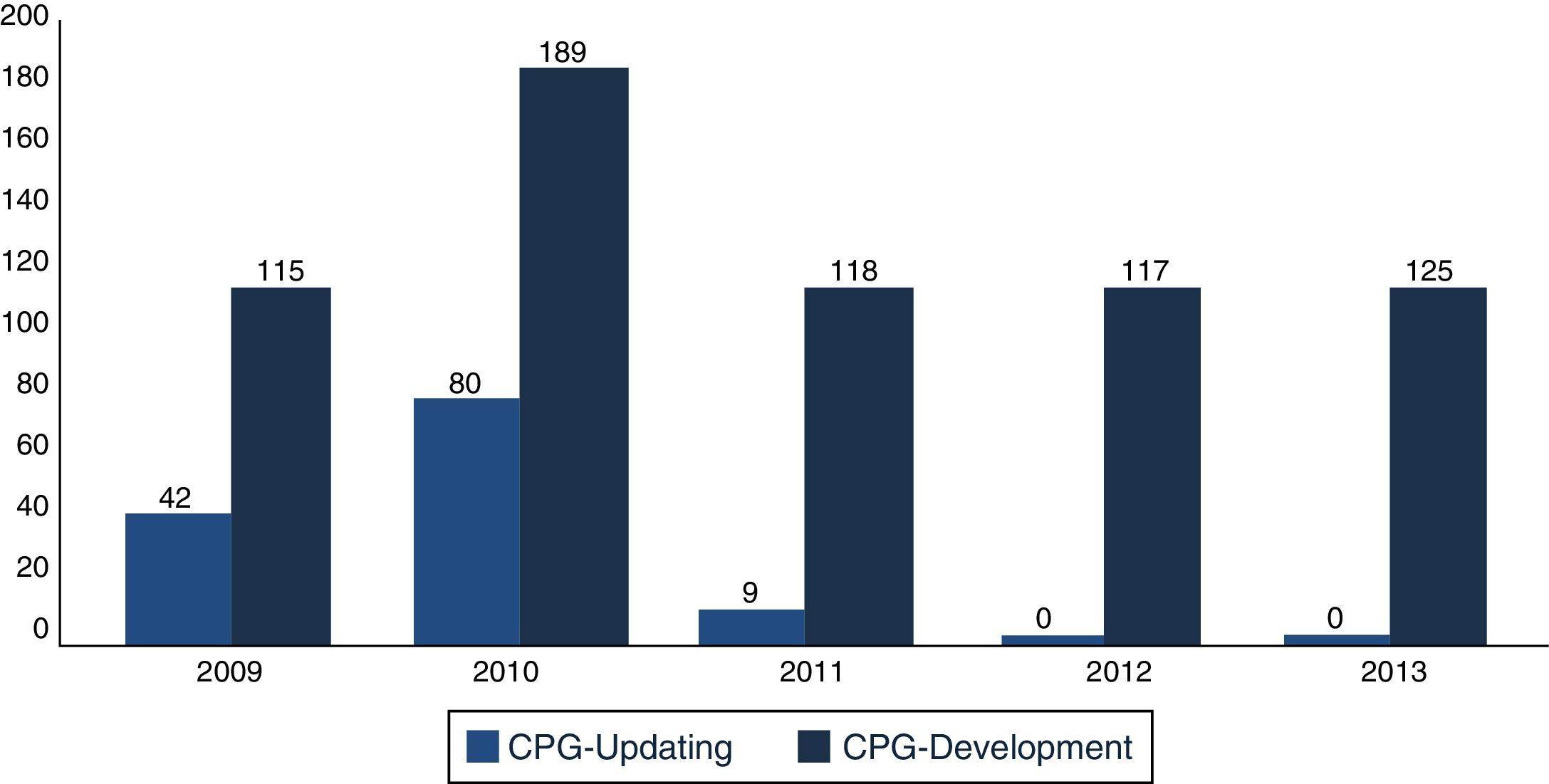

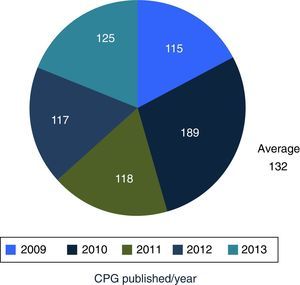

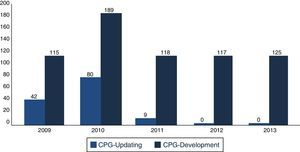

In December 2013, the Master Catalogue of clinical practice guidelines contained 664 published guidelines (Fig. 2), distributed into medical specialties: 42% are internal medicine, 22% surgery, 24% paediatrics and 2% gynaecology and obstetrics (Fig. 3).25 From the pool of guidelines pending updating, 31% were updated in accordance with the criteria established for them (Fig. 4).

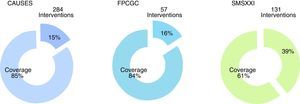

From the total of guidelines published in the Master Catalogue of clinical practice guidelines coverage of interventions by the National Commission of Social Protection in Health is granted at an 85% of the Universal catalogue of health services, an 84% of the Catastrophic expenses protection fund and a 61% of the XXI Century Medical Insurance (Fig. 5). Moreover, the clinical practice guidelines offer coverage to priority programmes such as maternal mortality, diabetes mellitus type 2, neoplasias and cardiovascular diseases.

Clinical practice guidelines published in the Master catalogue of clinical practice guidelines, by intervention coverage of the National Commission of Social Protection in Health (NCSPSH).

CAUSES: Universal catalogue of health services; NCSPSH: National Commission of Social Protection in Health; CEPF: Catastrophic expenses protection fund; XXIMI: XXI Century Medical Insurance.

At present, the Master Catalogue of clinical practice guidelines has approximately 2 million consultants, mainly in Mexico, and other countries including Peru, Unite States, Colombia, Equator, and Spain.

DiscussionMexico began to formally produce clinical practice guidelines in 2007, publishing its first 115 guidelines in 2009, and an average of 132 guidelines are published per year. Compared with the 6 centres developing guidelines in North America, Europe and Pacific, Mexico is the newest of them all.

The result is the sum of the efforts of inter-institutional coordination and cooperation from the Sistema Nacional de Salud, in which 3,477 health professionals have participated, through multi-disciplinary professionals consisting of GPs, specialist doctors and academics, as well as experts from different institutions and federal entities of the country.

At present, the 664 published guidelines demonstrate a standardised presentation format throughout the country, which promotes their reading and comprehension. These guidelines are available and accessible in the main portal of the coordinator centre (CENETEC-Salud) and the institutions which collaborate in its integration.

As a centre which develops the guidelines, one of its crucial goals is that all guidelines adhere to a protocol of bibliographical search, which has been agreed in such a way as to be reproducible, public and accessible. The coverage of interventions in the National Commission of Social Protection in Health are defined as the major objective (hospitalisation, emergencies and general surgery) and now is the moment to conduct an analysis of the published guidelines and establish the criteria for determining their validity and updating them to fit in with new guidelines in keeping with society's needs and those of the Sistema Nacional de Salud.

On an inter-institutional basis the editorial review process needs supporting so that a document without grammatical or design observations may be obtained. Without this, the final quality of the documents itself may be impacted even if there is no effect on the content of the evidence and recommendations.

The integration of the Master Catalogue of clinical practice guidelines has been a priority for the National Development plan and the Sectorial Health Programme in Mexico. The essential condition for its success is the commitment, will and coordination of the decision makers who are responsible for public health policies in Mexico. However, at the moment, it is essential to establish and reinforce the links which necessitate clinical practice guidelines in everyday medical practice: the training of health professionals, patient and family participation in healthcare, research into issues of scientific interest, standardisation of medical procedures and improvement of health organisations in general.

Within the limitations identified in the development of the guidelines, is the initial heterogeneity in handling medicine based on evidence. The capacity of its authors, resulting from the formation of the groups of experts, is thus of vital importance, as is its continuity throughout the development of the guideline.

The institutional strategies governing guideline dissemination have been reported in the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social. However, there is no proof of the impact their usage has created.26 There is therefore an urgent need for a strategy which would involve the Sistema Nacional de Salud in the dissemination, usage and follow up of how the clinical practice guidelines are being used, so that continuous feedback would be made towards their development, updating and optimisation.

The next stepsThe National Committee of Clinical practice guidelines will take the necessary measures to coordinate the methodology for updating and developing the new guidelines, updating methodology to involve epidemiological transition of the country and patient safety, and also develop cost-effectiveness analysis for taking health care decisions. The necessary strategies will also be formulated so that nongovernmental organisations may participate in the development and updating of the guidelines.

ConclusionsThe integration of the Master Catalogue of clinical practice guidelines, its dissemination and usage leads to accessibility to the best scientific evidence and recommendations applied to the country's population, promotes less variability of clinical practice guidelines, optimises planning and management of resources, and improves the quality of care and safety of the Sistema Nacional de Salud users.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sosa-García JO, Nieves-Hernández P, Puentes-Rosas E, Pineda-Pérez D, Viniegra-Osorio A, Torres-Arreola LP, et al. Experiencia del Sistema Nacional de Salud Mexicano en el desarrollo de guías de práctica clínica. Cirugía y Cirujanos. 2016;84:171–177.