In the surgical treatment of esophageal cancer, robotic surgery allows performing an intrathoracic handsewn anastomosis in a simpler, faster and more comfortable way for the surgeon than open surgery and traditional minimally invasive surgery. With this, we avoid the use of self-suture instruments, some of which require a small thoracotomy for their introduction. However, the retrieval of the specimen requires the practice of this thoracotomy, of variable size, that can be associated with intense chest pain. We describe a technical modification of the classic robotic Ivor Lewis that allows removal of the surgical piece through a minimal abdominal incision, thus avoiding controlled rib fracture, as well as the possible sequelae of making an incision in the chest wall.

En el tratamiento quirúrgico del cáncer de esófago, la cirugía robótica permite realizar una anastomosis manual intratorácica de manera más sencilla, rápida y cómoda para el cirujano que la cirugía abierta y la cirugía mínimamente invasiva tradicional. Con ello, evitamos el uso de instrumentos de autosutura, algunos de los cuales precisan una pequeña toracotomía para su introducción. No obstante, la extracción de la pieza exige la práctica de esa toracotomía, de tamaño variable, y que puede asociar dolor torácico intenso. Describimos una sencilla modificación técnica del Ivor Lewis robótico clásico que permite la extracción de la pieza quirúrgica por una mínima incisión abdominal, evitando la necesidad de fracturar costillas de forma controlada así como las posibles secuelas de practicar una incisión en la pared torácica.

Two-stage transthoracic oesophagectomy has undergone several changes since it was described in 1946 by Ivor Lewis.1 Laparotomy and right thoracotomy have given way to minimally invasive approaches that seek to perform the correct oncological resections, thus reducing surgical aggression and the sequelae of the operation, among other parameters. In relation to postoperative pain, performing a right thoracotomy has promoted the application of epidural analgesia in order to control this adequately, favouring the patient's collaboration in their respiratory recovery. Minimally invasive surgery, the latest example of which is robotic-assisted surgery, reduces post-surgical pain but does not remove it completely, as a small thoracotomy, at least 6 cm, is still required, either for the insertion of autosuture instruments (circular endostaplers) and/or for the extraction of the surgical specimen.2

Our objective is to describe a technical modification in the original procedure that enables the surgical specimen to be extracted through a small laparotomy, with the patient presenting only small incisions in the chest wall, corresponding to the orifices of the trocars.

Surgical techniqueThis technique can be performed in all patients who have carcinoma of the oesophageal-gastric junction or oesophagus, middle third and distal third, and who, after neoadjuvant or non-adjuvant treatment, are candidates for minimally invasive or robotic-assisted transthoracic oesophagectomy. Although we have not detected this to date, this could be difficult in cases of large T3-T4 tumours, in which case, it would be advisable to extend the dimensions of the hiatus, sectioning both pillars.

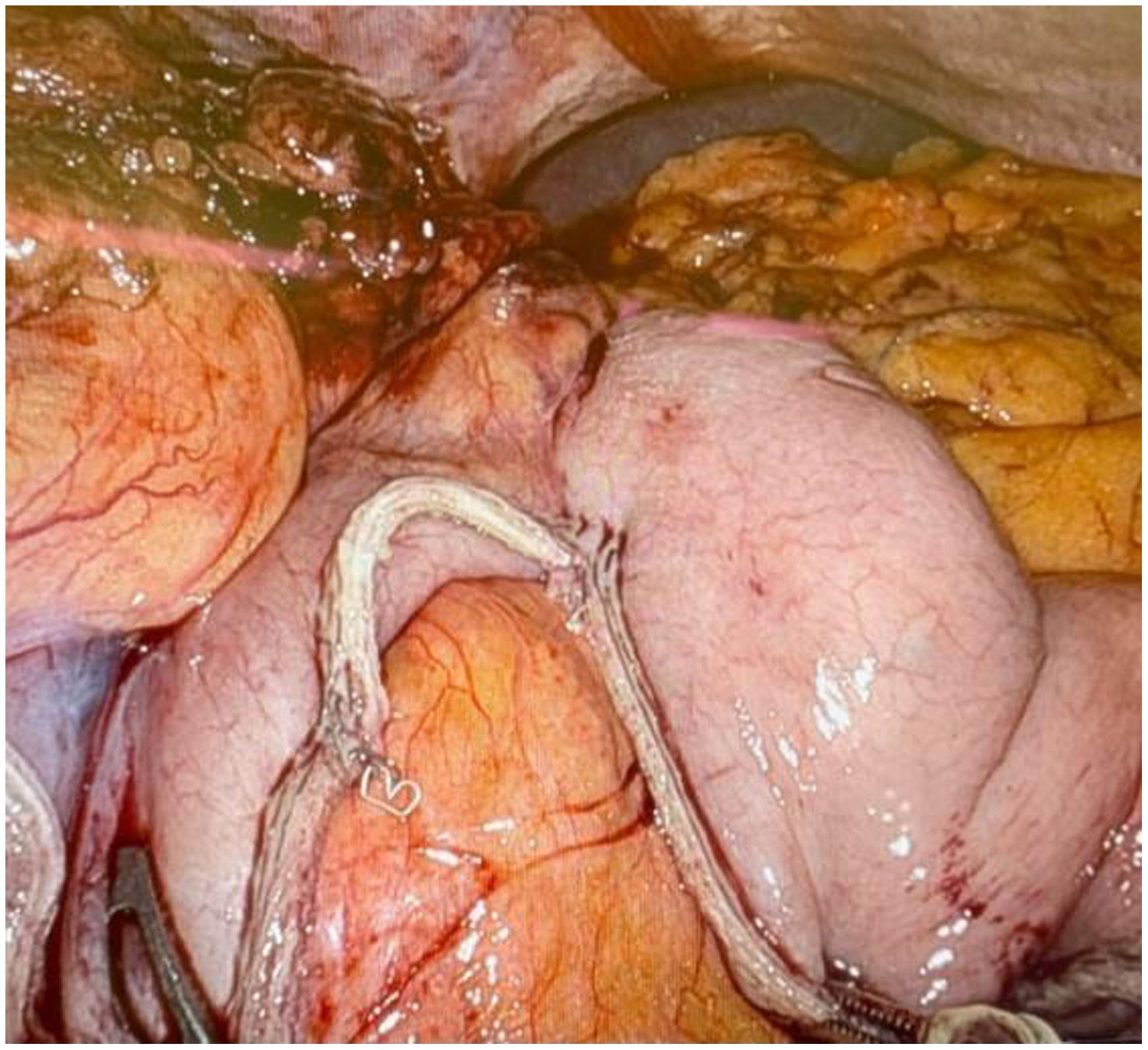

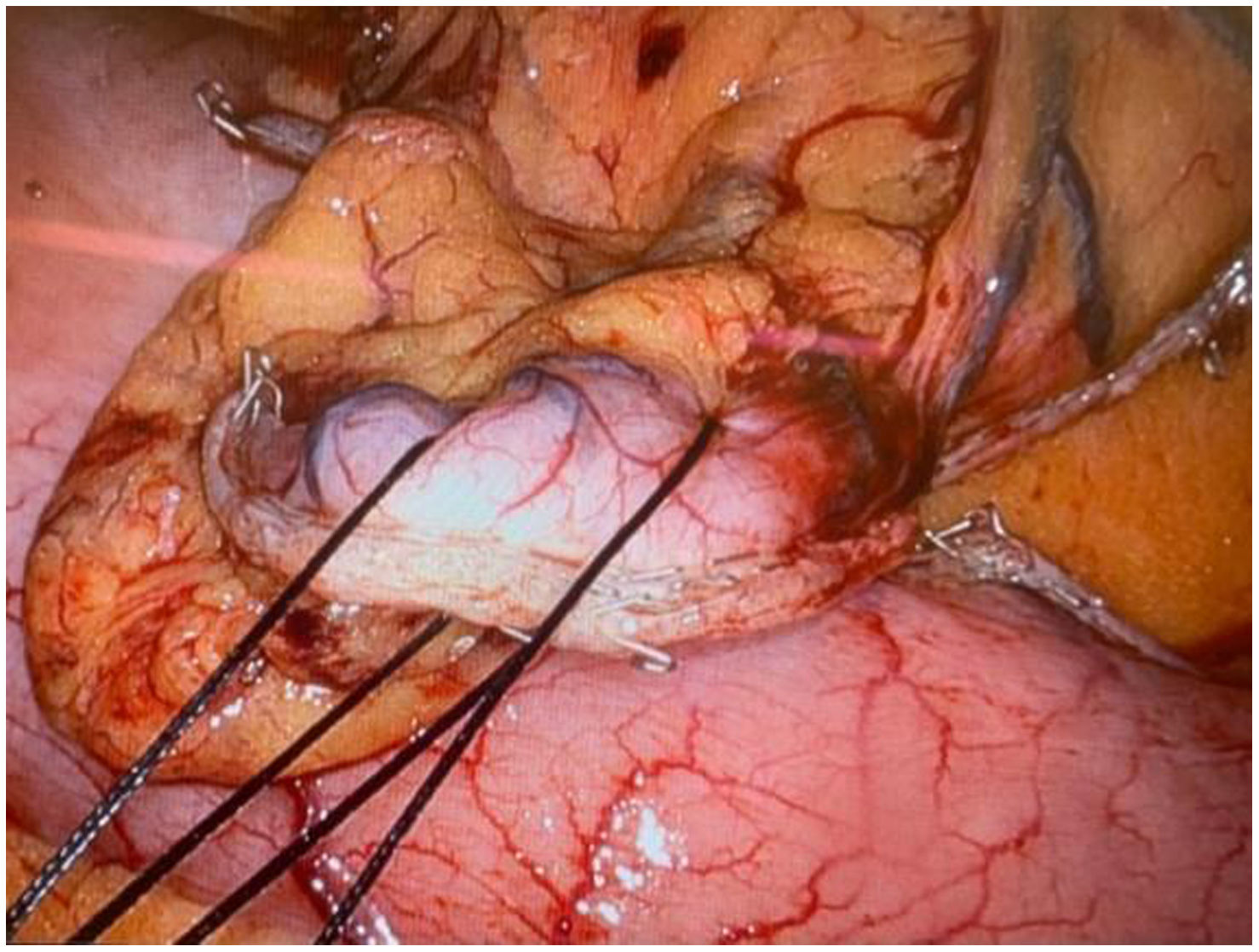

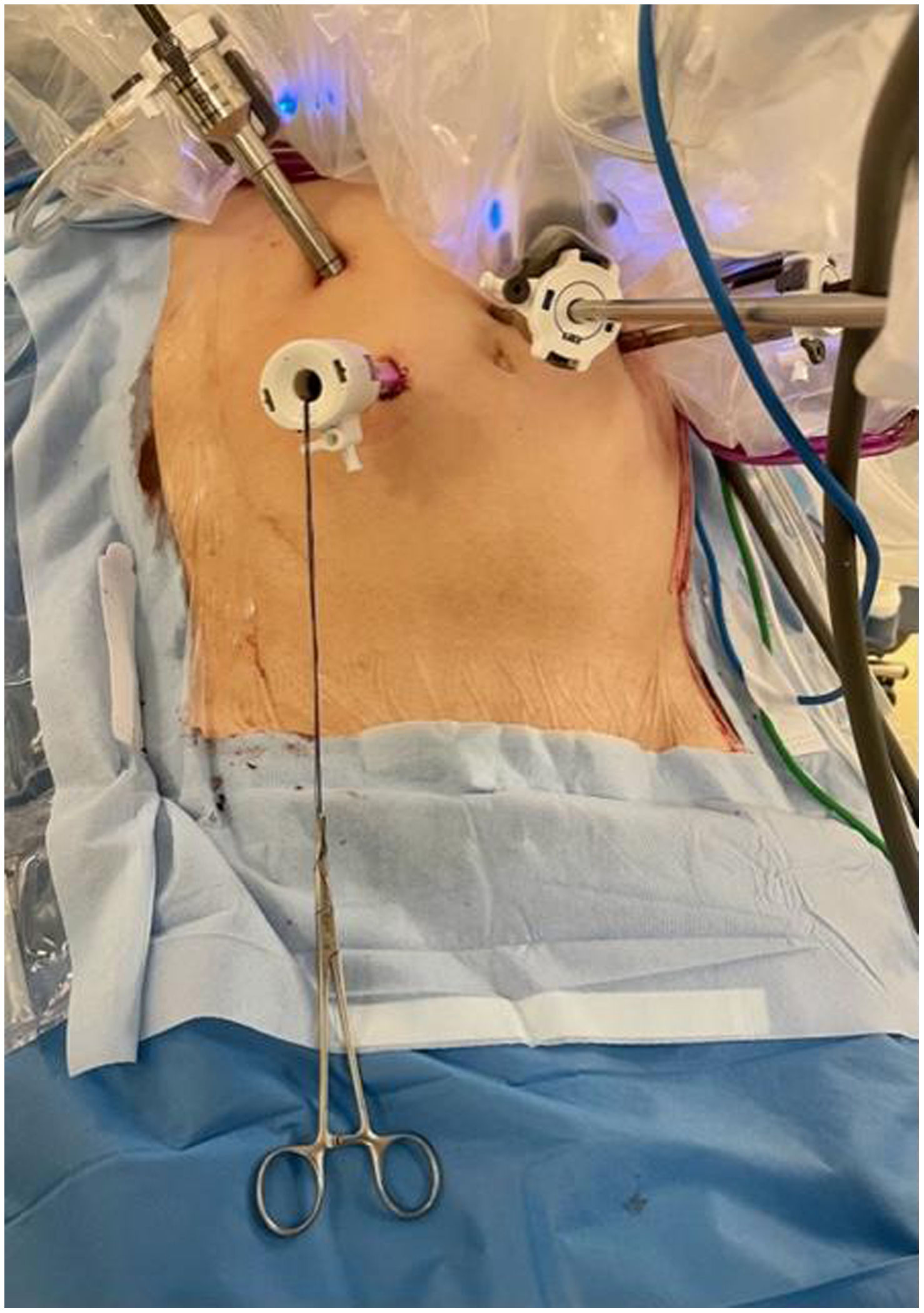

In the abdominal stage, after gastrolysis and lymphadenectomy has been performed, the gastroplasty is configured by means of several linear endostapler loads, in the caudo-cranial direction. The connection between the part and the plasty must be short, no more than 3 cm in length (Fig. 1), in order to be able to access the plasty without difficulty from the thoracic cavity, enabling definitive clamping and separation with maximum ease. Finally, we apply 2 silk stitches from zero to the distal end of the surgical part (Fig. 2), which we extract through the hole located in the right midclavicular line, and which corresponds to the accessory trocar (Fig. 3). Once the hemostasis of the surgical site and the entry points have been reviewed, the patient's position is moved to left semi-prone and thoracic stage begins.

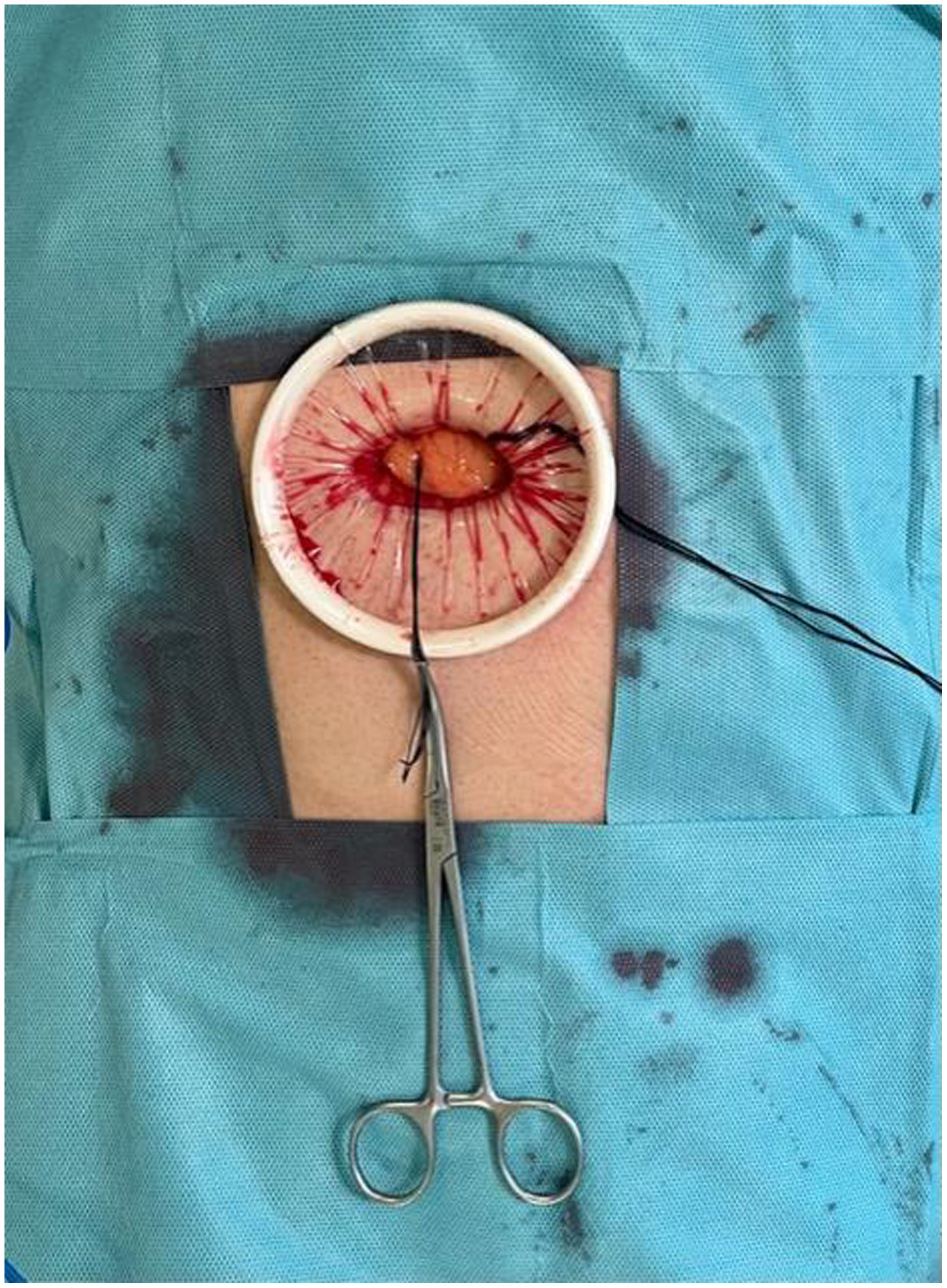

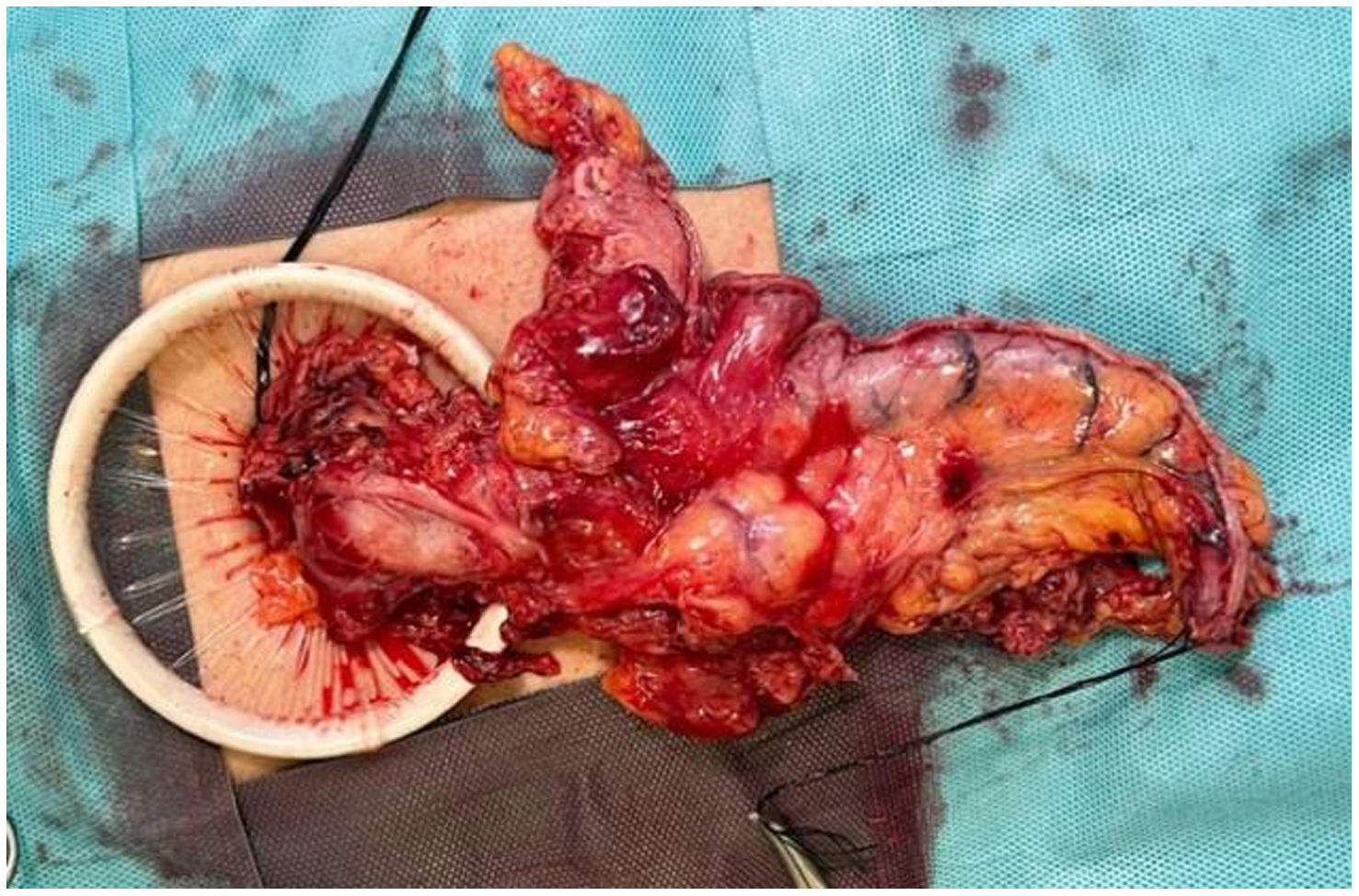

The corresponding dissection and lymphadenectomy are performed in the thoracic stage. Once the oesophageal cut-off point has been decided, this is carried out in layers by electrocoagulation. This makes it possible for an oesophageal mucosal impeller to perform a manual biplane suture. The proximal boundary of the specimen is sectioned 1−2 cm from the end with an endostapler, to avoid contamination and to refer it intraoperatively for anatomopathological analysis if deemed necessary. Subsequently, with forceps through robotic arms 2 and 4, the specimen is gently pulled in a cranial direction until the upper end of the plasty and the portion that joins it to the specimen are visualized. By means of a robotic endostapler, both structures are separated, ascending the plasty to the thoracic cavity while the assistant pulls the specimen caudally through the silk threads externalized in the abdominal wall. Once the manual oesophagogastric suture is completed and the drain is placed, the entry ports are closed and the patient's position is changed to supine for extubation. The entry hole of the accessory trocar is then extended to a maximum of 3−4 cm transversely and an Alexis system is introduced (Fig. 4). Finally, the surgical specimen is removed (Fig. 5) by removing the device and closing the small laparotomy (Fig. 6).

Minimally invasive surgery arises from the need to lessen surgical aggression, reduce the sequelae of operations and promote the early recovery of patients. In this direction, many studies have demonstrated its benefit in relation to postoperative pain and analgesic needs, compared to traditional approaches. Thoracotomy during Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy has determined the need for epidural analgesia, in addition to being associated with a non-negligible rate of respiratory complications. In fact, transthoracic oesophagectomy using laparoscopy and thoracoscopy has been shown to produce less pain, lower rates of pneumonia, and a reduction in hospital stay compared to classic or hybrid approaches.3 However, it is still necessary to perform a small thoracotomy and even controlled sectioning of ribs, either to introduce circular endostaplers into the chest cavity with which to make the anastomosis or to extract the surgical specimen. Dalmonte et al.4 describe the transabdominal extraction of the surgical specimen, however they perform this during the abdominal stage by transhiatal dissection and sectioning of the oesophagus from the abdomen above the tumour. This procedure is not applicable in the case of tumours of the upper middle third, which cannot be reached by the cranial section by this approach. In addition, they require a small thoracotomy to subsequently perform the anastomosis with a circular endostapler. The surgical specimen corresponding to the thoracic lymphadenectomy must be extracted through the thoracic entry ports. They also describe the fixation of the plasty to the right abutment and then retrieve and ascend it during thoracoscopy. This carries a risk of accidental release of the plasty and unwanted descent into the abdominal cavity during the thoracic stage. In our case, the resection is en bloc, applicable not only to Siewert II cardiac tumours, and by ascending the plasty attached to the part, the risk of gastroplasty descent is minimized. So far, we have not observed immediate or short-term complications, such as eventrations of the mini-laparotomy used for the extraction of the specimen, in the series of 6 patients.

On the other hand, the use of robotic systems in surgery improves the visualisation of the surgical field, permits greater mobility and angulation of the instruments, facilitates the dissection of structures, application of stitches and suturing in less space. All this makes manual oesophagogastric anastomosis easier than through thoracotomy or thoracoscopy, avoiding the introduction of instruments, some of which have a calibre greater than 2 cm.

In summary, the technical modification described is simple, risk-free in our experience, and enables us to minimise surgical aggression by avoiding the performance of a thoracotomy during robotic Ivor Lewis oesophagectomy.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Conesa Plá A, Martín DRA, Ruiz VM, Haro LFM. Ausencia de toracotomía mediante la sutura manual intratorácica y la extracción transabdominal de la pieza quirúrgica durante la esofaguectomía robótica de Ivor Lewis. Cir Esp. 2024;102:99–102.