Leakage from the colorectal anastomosis is one of the most feared complications after rectal cancer surgery1. When faced with this complication, the management strategy must be individualized to control the septic focus and try to preserve the intestinal continuity2,3. The combined transanal and transabdominal approach is an emerging treatment for anastomotic leaks3,4. The objectives of associated transanal revision during surgical reoperation are to assess the state of the tissues and the extent of the defect in order to carry out local treatment5. The current trend is to try to repair the defect, performing it in the first reoperation or in a second intervention after applying vacuum therapy and having achieved better control of the septic focus. This strategy aims to reduce the morbidity and mortality of this complication, preserve and reconstruct viable anastomoses, reduce the incidence of chronic anastomotic sinuses, and clearly identify those that must be dismantled.

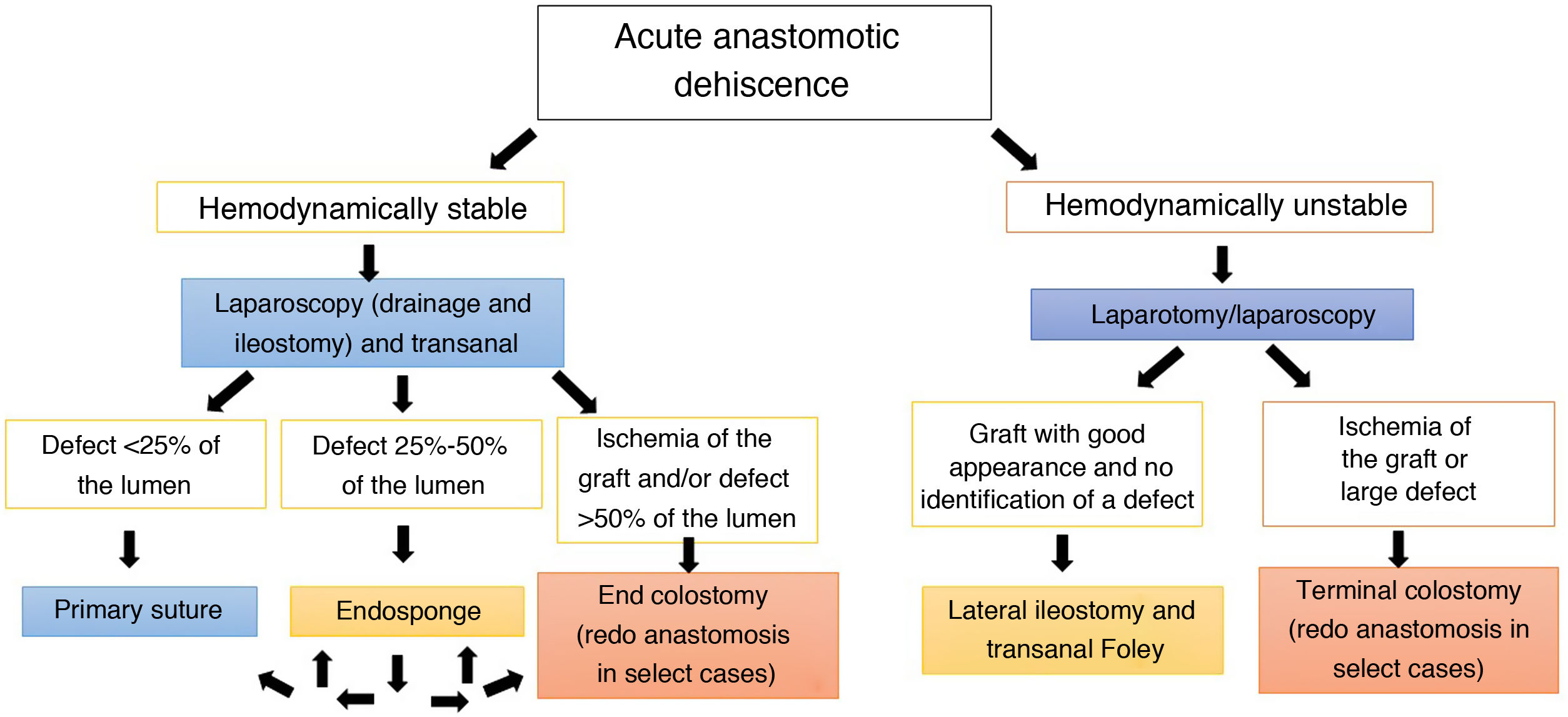

We want to share our current algorithm for reoperation due to acute extraperitoneal anastomotic dehiscence (Fig. 1).

In our algorithm, the suture or closure of the anastomotic defect may be performed when the dehiscence is small (<25%), the tissues are in good condition, the perianastomotic drainage is guaranteed from the abdominal field, and it is accompanied by a lateral ileostomy with lavage of the remaining colon. The suction drainage system (Endo-Sponge, Braun Medical®) is reserved for cases with intermediate defects and no ischemia. Closure of the defect will be attempted after 2–3 changes. In the event of major defects or failure of vacuum therapy, redo anastomosis or end colostomy is considered6.

In a situation of hemodynamic instability/septic shock, priority should be given to draining the septic focus and performing an ostomy (if not already existing). If there is no obvious ischemia, lateral ileostomy is better than colostomy7. Subsequently, and depending on the clinical evolution, another transanal revision surgery could be considered as a second procedure in order to repair the dehiscence when possible, apply vacuum therapy to improve drainage, or undo the anastomosis.

These treatment schemes must be accompanied by multimodal rehabilitation strategies (so that the patient is in the best physical, nutritional and psychological condition to confront an adverse event)8 and proactive programs for the early detection of dehiscence9.

Since 2017, our experience with the application of the algorithm has increased progressively. Between January 2017 and May 2022, we have reoperated on 21 patients for acute extraperitoneal anastomotic dehiscence with a 90-day postoperative leakage rate of 7.6%. On 15 occasions, the protocol was followed optimally (71%).

Among the patients who were managed in accordance with the protocol, 14 were treated with a combination of abdominal laparoscopic surgery and transanal revision. Due to the instability of one patient, we conducted an exclusively abdominal approach with an associated lateral ileostomy.

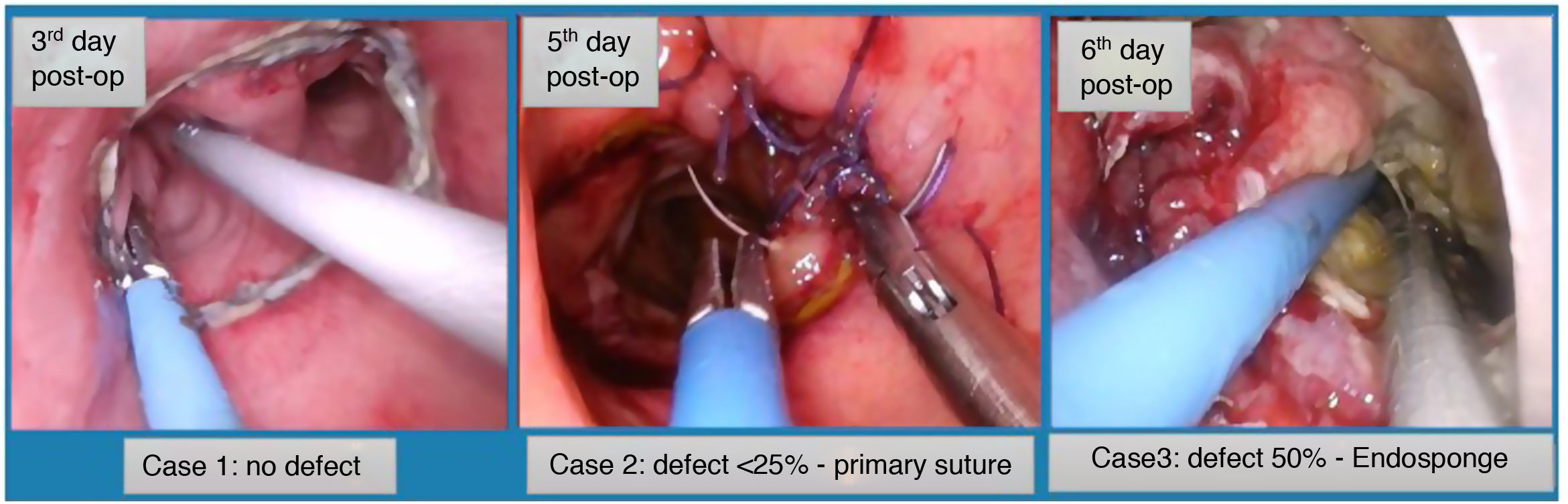

We conducted a TAMIS transanal approach in 86% of patients, while direct transanal access was used in 14% (2 cases) as they were ultra-low anastomoses. In 12 out of the 14 patients, we were able to perform an anastomosis-preserving strategy: in 8, the defect was closed; in 3, no anastomotic defect was identified during the TAMIS revision; and in one, the evolution was favorable with vacuum therapy, but the defect could not be closed. In all cases, the anastomosis was preserved, and the ileostomy was subsequently closed. On 2 occasions, the transanal findings indicated non-viability of the anastomosis with dehiscence greater than 50% due to ischemia of the graft. In the first case, the anastomosis was dismantled, and an end colostomy was created. In the second case, the side-to-side colorectal anastomosis was dismantled and a new manual coloanal anastomosis was performed. This patient developed graft ischemia and had to be reoperated to create an end colostomy, with a good subsequent evolution (Fig. 2).

Out of the 6 cases where the protocol was not applied, the patients were treated by abdominal access on 4 occasions (2 laparoscopy with conversion, one laparoscopy and one laparotomy), with 2 lateral ileostomies and 2 terminal colostomies. The other 2 cases were patients with ultra-low manual coloanal anastomoses with previous protective ileostomy and dehiscences with few clinical repercussions; these patients were treated with transanal drainage alone. All of these cases were left out of the algorithm.

In our case series about anastomotic leakage, we have had no mortalities.

Treatment of leaks must be individualized based on the patient’s clinical status, comorbidities, level of the anastomosis, presence or absence of a diverting stoma, and the time elapsed between the initial surgery and the diagnosis of the dehiscence2,3. The purpose of having an algorithm for the treatment of anastomotic dehiscence is to be able to systematize the management of one of the most feared complications of colorectal surgery.

The objective of sharing the algorithm is to show our evolution in the management of anastomotic leakage, as well as the establishment of systematic transanal revision in extraperitoneal dehiscence and the selective use of vacuum therapy. In cases of dehiscence, the priority is to drain the septic focus and divert the stool (if possible, with a lateral ileostomy). However, we have evolved towards trying to repair the anastomosis to avoid chronic sinus10, and thereby be able to increase the rate of ostomy closure and clearly identify those that should be dismantled. Time will tell if this also improves the functionality and the quality of life of our patients.