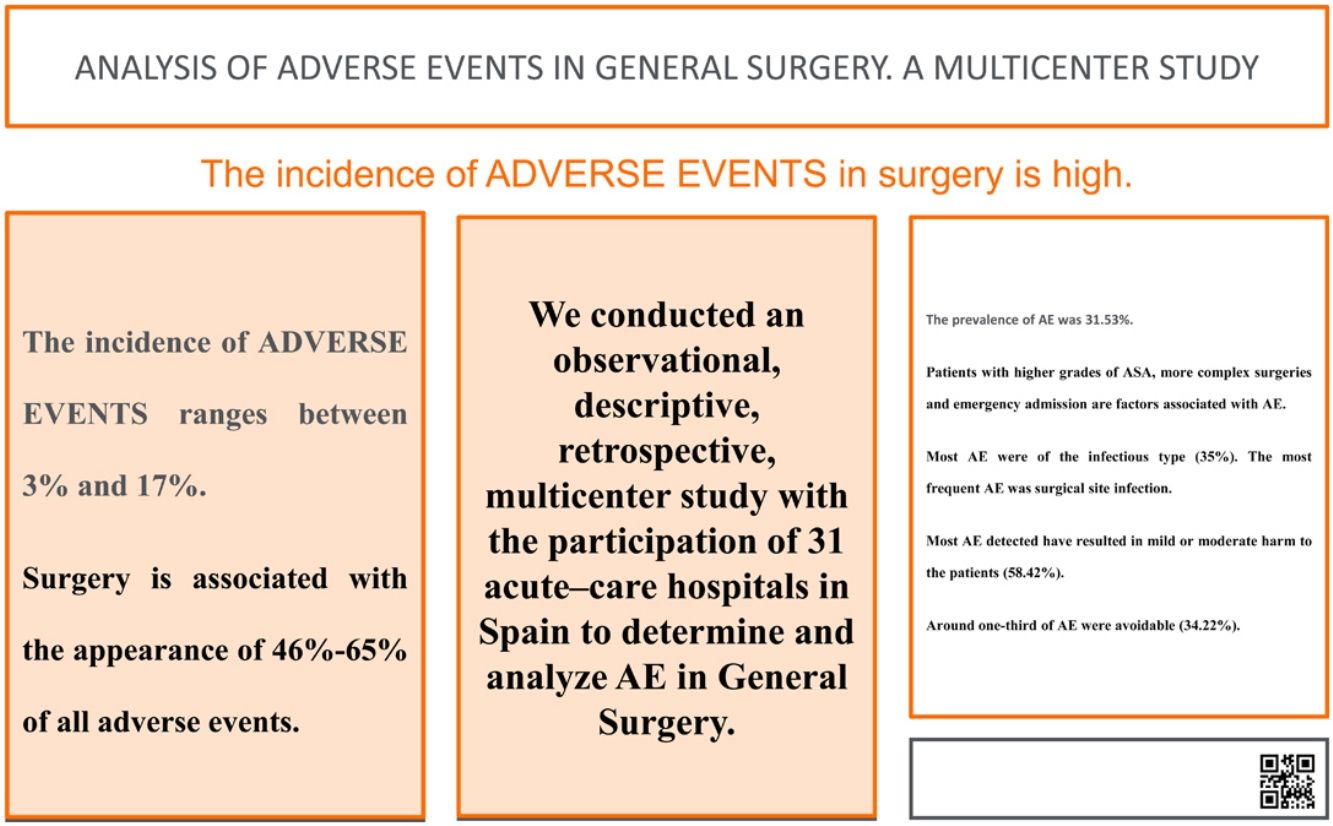

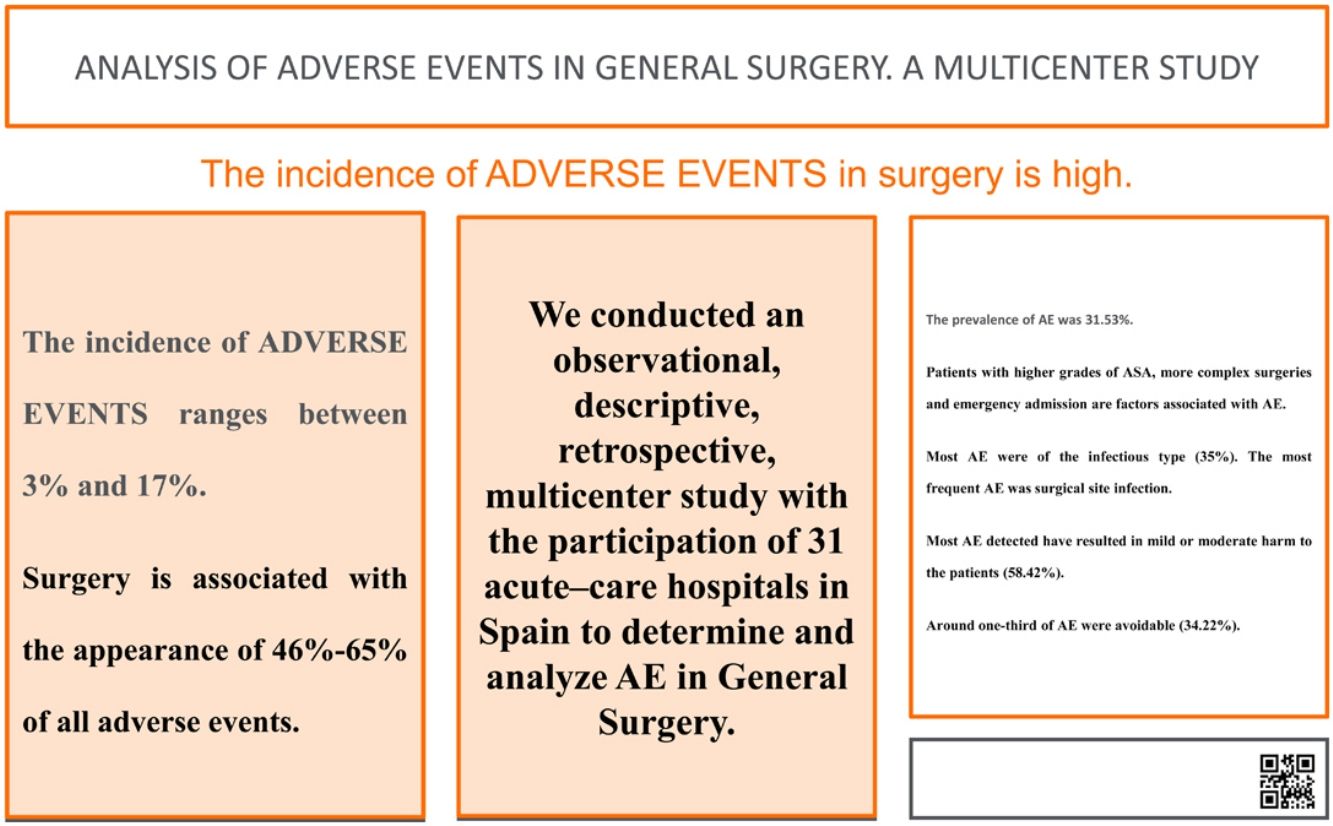

Knowledge of adverse events (AE) in acute care hospitals is a particularly relevant aspect of patient safety. Its incidence ranges from 3% to 17%, and surgery is related to the occurrence of 46%–65% of all AE.

Material and methodsAn observational, descriptive, retrospective, multicenter study was conducted with the participation of 31 Spanish acute-care hospitals to determine and analyze AE in general surgery services.

ResultsThe prevalence of AE was 31.53%. The most frequent types of AE were infectious (35%). Higher ASA grades, greater complexity and urgent-type admission are factors associated with the presence of AE. The majority of patients (58.42%) were attributed a category F event (temporary harm to the patient requiring initial or prolonged hospitalization); 14.69% of AE were considered severe, while 34.22% of AE were considered preventable.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of AE in General and GI Surgery (GGIS) patients is high. Most AE were infectious, and the most frequent AE was surgical site infection. Higher ASA grades, greater complexity and urgent-type admission are factors associated with the presence of AE. Most detected AE resulted in mild or moderate harm to the patients. About one-third of AE were preventable.

El conocimiento de los eventos adversos (EA) en los hospitales de agudos es un aspecto de especial relevancia en la seguridad del paciente. Su incidencia oscila entre un 3%–17% y la cirugía se relaciona con la aparición de entre un 46%–65% de todos los EA.

Material y métodosSe realiza un estudio observacional, descriptivo, retrospectivo y multicéntrico, con la participación de 31 hospitales de agudos españoles, para la determinación y análisis de los EA en los Servicios de cirugía general.

ResultadosLa prevalencia de EA fue del 31,53%. Los tipos de EA más frecuentes fueron de tipo infeccioso (35%). Los pacientes con mayores grados de ASA, mayor complejidad y un tipo de ingreso urgente son factores asociados a la presencia de EA. A la mayoría de los pacientes se les atribuyó una categoría de daño F (daño temporal al paciente que requiera iniciar o prolongar la hospitalización) (58,42%). El 14,69% de los EA se considerados graves. El 34,22% de los EA se consideraron evitables.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de EA en pacientes de CGAD es elevada. La mayor parte de los EA fueron de tipo infeccioso. El EA más frecuente fue la infección de herida o sitio quirúrgico. Los pacientes con mayores grados de ASA, mayor complejidad y un tipo de ingreso urgente son factores asociados a la presencia de EA. La mayoría de los EA detectados han supuesto un daño leve o moderado sobre los pacientes. Alrededor de un tercio de EA fueron evitables.

Knowledge of adverse events (AE) in acute-care hospitals is an important factor of patient safety (PS) and has been the subject of multiple national and international campaigns aimed at reducing the high numbers of preventable AE. In patients hospitalized in the United States, Australia, Canada, England and New Zealand, AE rates in hospitals range from 4% to 16%, approximately, 50% of which are considered preventable.

The Harvard Medical Practice Study (HMPS),1 a pioneer in the analysis of AE, has reported an incidence of AE of 3.7%. The specialties with the highest number of AE were surgical specialties (16.1%), while medical specialties presented the lowest rate (3.6%).

In the study by Vincent et al. conducted at 2 London hospitals, the authors found an incidence of AE of 10.8%, 48% of which were preventable. The specialty with the most AE was General Surgery, affecting 16.2% of patients.

In 2000, Davis et al. in New Zealand and Baker et al. in Canada obtained AE rates of 12.9% and 7.5%, respectively, and the surgery service had produced the majority of the AE.

The highest AE rates were reported by the Healey study, which was carried out in Vermont from 2000 to 2001 and included 4743 patients, who were followed prospectively. The authors found an AE rate of 31.5% (48.6% preventable). They attributed such high rates (4–6 times higher) to the fact that the study included exclusively surgical patients, had a broader definition of AE, and was designed prospectively.

In the ENEAS Study in Spain, the incidence of patients with AE directly related to hospital care was 8.4%, and approximately half were considered preventable (42.6%). The specialties who presented the highest incidence of AE were cardiac (20%), thoracic (20%), vascular (16.9%), urology (10.4%) and general (10.3%) surgery. Therefore, surgery services are considered high-risk for the presentation of AE.

The most common source for identifying AE are the administrative healthcare databases, mainly through a search for indicators of complications, according to the methodology proposed by the AHRQ (Patient Safety Indicators), or the review of medical records, with a screening questionnaire to determine the pertinence of the documentation for subsequent review.1 However, other studies carried out in our country using the trigger methodology (aspects of care associated with highly frequent AE) have reported AE rates >30%, both in medical specialties as well as in General Surgery.2–5

Considering the previous data and given the enormous relevance of AE in surgery, the present study was proposed to determine the AE present in the General Surgery and Digestive System Services, as well as to analyze their characteristics.

MethodsWe designed a retrospective, descriptive, observational, multicenter study for the identification and characterization of AE in General and Gastrointestinal Surgery (GGIS) services using clinical records for identification. Our study analyzed patients who had been treated surgically by the GGIS service from September 1, 2017 to May 31, 2018.

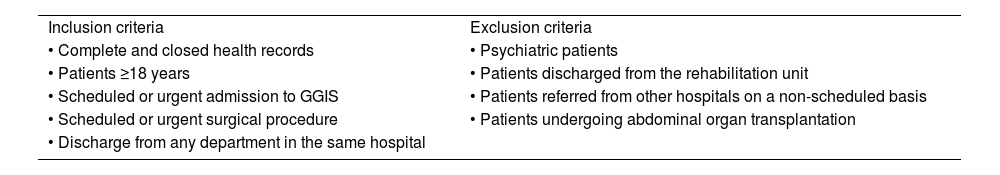

Inclusion and exclusion criteria are listed in Table 1. We calculated the sample size with an estimated probability of AE of 30% based on a population of some 80 000 annual surgical interventions by the participating surgery departments, a confidence level of 95% and a precision of 3%, which resulted in a sample size of 887 hospital records, distributed among the participating hospitals. To prevent loss of cases and data from affecting the estimated sample size, each participating study center was asked to include data for 40 patients.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| • Complete and closed health records | • Psychiatric patients |

| • Patients ≥18 years | • Patients discharged from the rehabilitation unit |

| • Scheduled or urgent admission to GGIS | • Patients referred from other hospitals on a non-scheduled basis |

| • Scheduled or urgent surgical procedure | • Patients undergoing abdominal organ transplantation |

| • Discharge from any department in the same hospital |

Each participating study center had at least one reviewer, who was either specialized in surgery or a resident doctor from the third year of specialty. Reviewers were trained by the research team using a video tutorial. Likewise, an instruction manual was created for the reviewers. When necessary, training was completed through individual training.

The project research team also acted as a consultant in cases in which there were doubts about specific cases in the detection of AE and their characteristics.

AE was defined as any unintentional harmful event that occurs to the patient as a consequence of healthcare that is not related to the natural evolution of their disease.6 When an AE was detected, a harm category was assigned, and the degree to which the situation could have been avoided was assessed. To determine the avoidable nature of the AE, the classification used in the ENEAS study was applied.7,8

The harm category was classified using a scale adapted from the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP)9 from categories E to I.

- -

Category E: temporary harm to the patient requiring intervention

- -

Category F: temporary harm to the patient requiring initial and/or prolonged hospitalization

- -

Category G: permanent harm

- -

Category H: harm requiring intervention to sustain life

- -

Category I: death of the patient

The preventability classification from the ENEAS study was used9:

- 1

Lack of evidence

- 2

Minimal probability

- 3

Mild probability

- 4

Moderate probability

- 5

Very likely

- 6

Total evidence

An AE that obtained a score greater than or equal to 4 was considered avoidable.

The AE were classified according to Table 2.

AE classification.

| AE classification: |

| • AE associated with the surgical incision: |

| - Surgical site infection |

| - Seroma |

| - Hematoma |

| - Laparotomy dehiscence |

| • AE associated with cancelled surgery |

| • Intraabdominal complication: |

| -Anastomotic fistula |

| - Intraabdominal collection |

| - Intraabdominal bleeding |

| -Idiopathic paralytic ileus |

| • Cardiorespiratory: |

| -Fluid overload and respiratory distress |

| • Urologic: |

| - Acute urine retention |

| - Urinary tract infection |

| • AE related to venous access: |

| - Central line infection |

| - Phlebitis of the peripheral iv |

| - Extravasation |

| • AE related to basic care: |

| - Poor analgesic control requiring attention |

| - Disorientation |

| - Ulcers due to decubitus |

| - Allergic reactions to medication |

| • Complication of a procedure (invasive) |

| • Hypocalcemia after thyroidectomy |

| • Other (not included in the former) |

A descriptive analysis was performed of the study population characteristics using absolute and relative frequency for the categorical variables and mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range for continuous variables, in accordance with the normality test (Kolmogorov Smirnov test).

The comparison of the main variables according to the presence or absence of AE was carried out using the non-parametric Mann-Whitney U, Student’s t, chi-square, or Fisher’s exact test, depending on its nature.

A prevalence study of AE was carried out by calculating the percentage of patients with at least one associated AE.

Data were collected in the RedCap Database and analyzed in the SAS statistical program for Windows, version 9.4. All analyses in the study used a significance level of 5%.

ResultsThe total number of records was 1132, which were entered according to the distribution by the 31 hospitals (Fig. 1). According to the 2018 national hospital audit, there were 120 records (11%) from hospitals with less than 200 beds, 455 records (40%) from hospitals with 200−500 beds, 396 records (35%) from hospitals with 501–1000 beds, and 161 records (14%) in hospitals with more than 1000 beds.

Average patient age was 58.15 years, with a minimum of 18 years and a maximum of 94. The average stay was 6.56 days, with a standard deviation of 14.32. There were 555 (49%) women and 577 (51%) men. 75.0% of the patients underwent scheduled surgery (849 patients), and 25.0% underwent urgent surgery (283 patients).

Out of the 1132 records in which the main diagnosis of the pathology (or the reason for admission) was specified, the most frequent was cholelithiasis (13.1%), followed by inguinal hernia (7.9%) and appendicitis (7.2%).

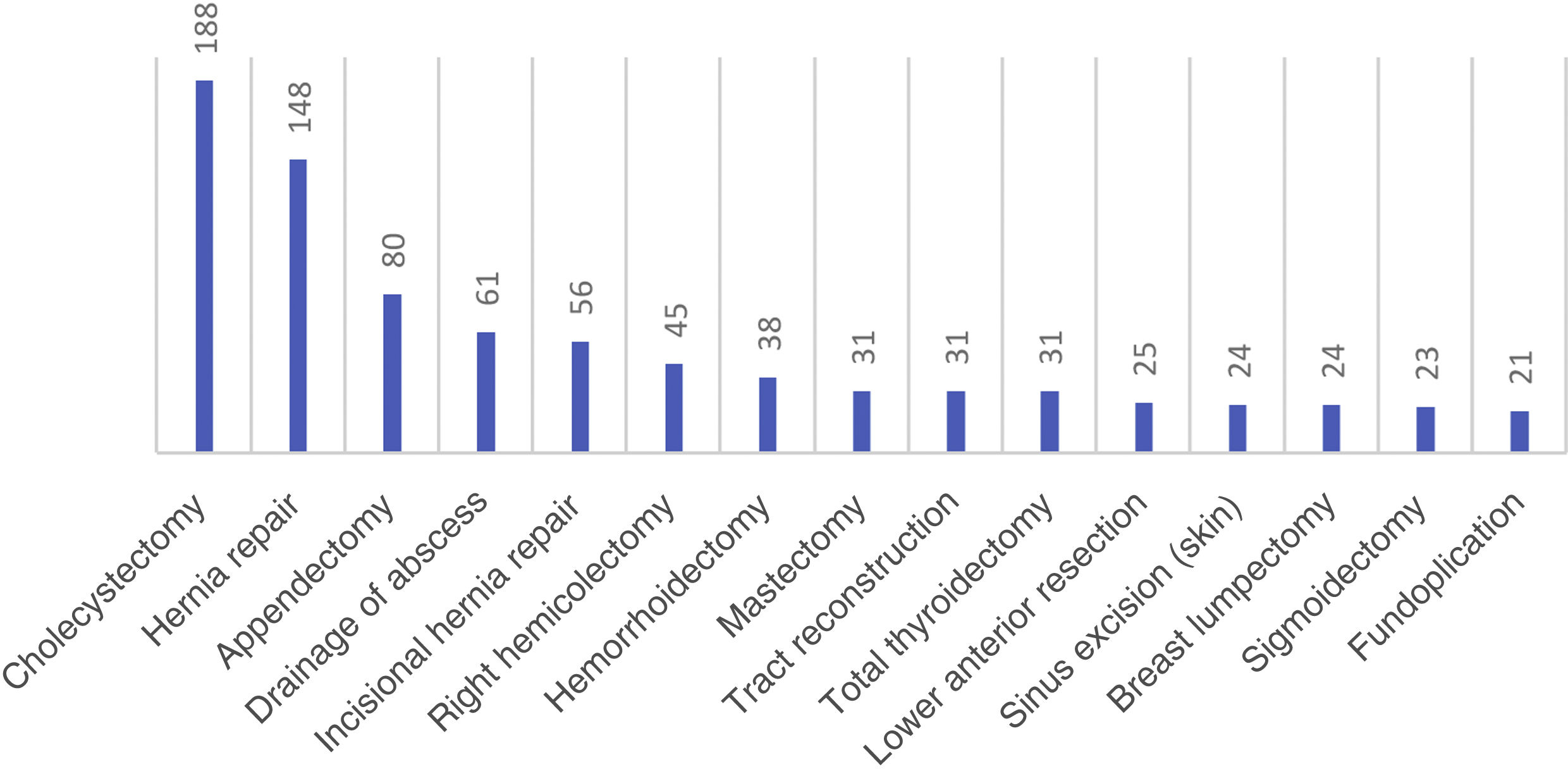

The most common procedure was cholecystectomy, followed by hernioplasty and appendectomy. The 15 most frequently registered primary procedures are shown in (Fig. 2).

Regarding the complexity of the surgical interventions, we found that 36.9% (418 records) of interventions had a low level of complexity, and 10% (113 records) were highly complex interventions. The remaining 52.9% were classified as procedures with moderate complexity (30.8% low medium complexity and 22.1% high medium complexity).

In terms of anesthetic risk, 54.07% were classified as ASA II.

The prevalence of adverse events was 31.54% (357 patients of the 1132 analyzed presented at least 1 AE). In total, 599 AE were found in all the records evaluated. Moreover, 69 patients had a second AE (6.10%), 28 a third AE (2.47%) and 16 patients had a fourth AE (1.41%).

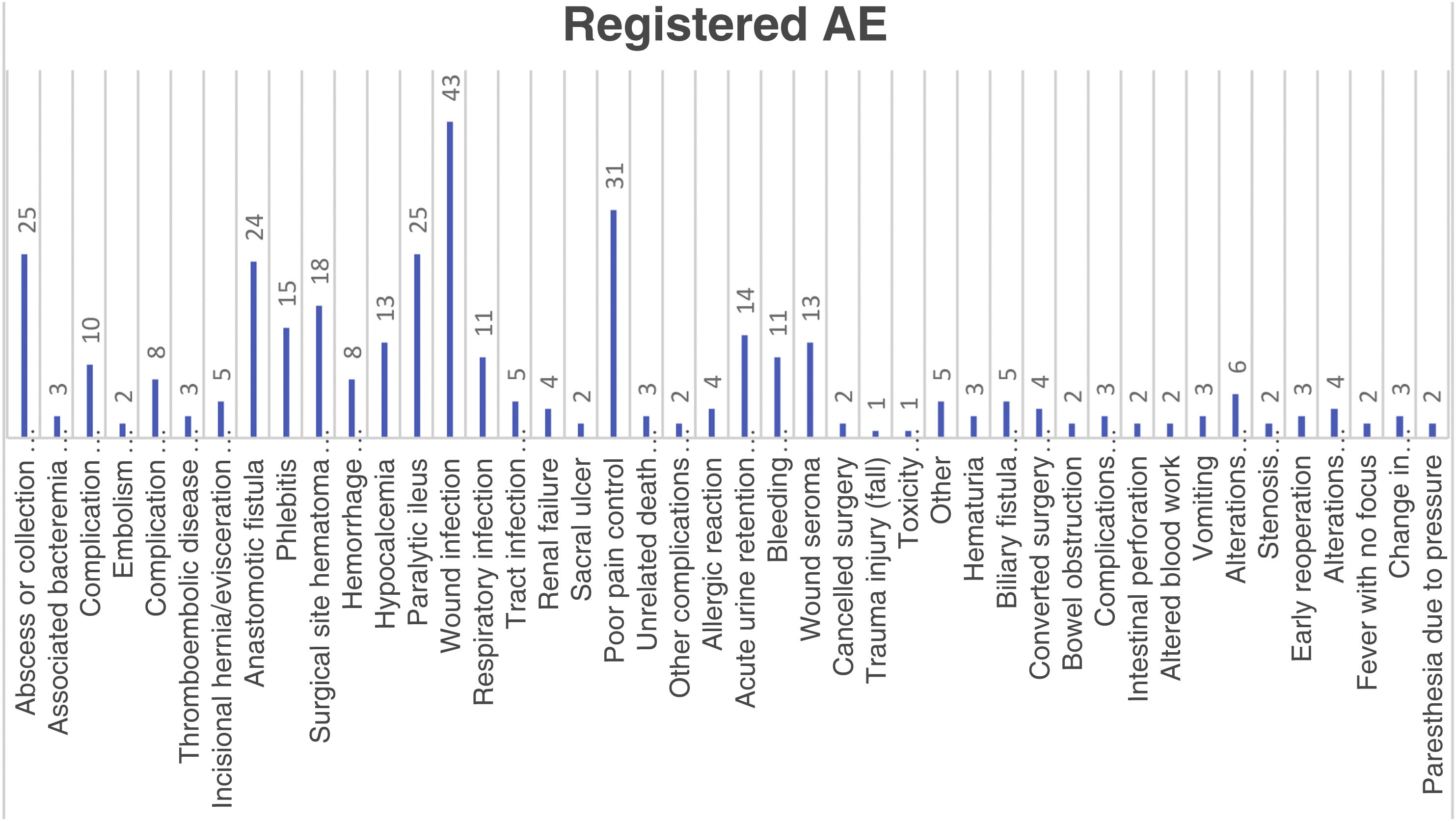

The most frequent group of AE was the infectious type, accounting for 35% of the total (126 records). The most common AE was wound or surgical site infection (43 patients), followed by poor pain control, intra-abdominal abscess, paralytic ileus, and anastomotic fistula (Fig. 3).

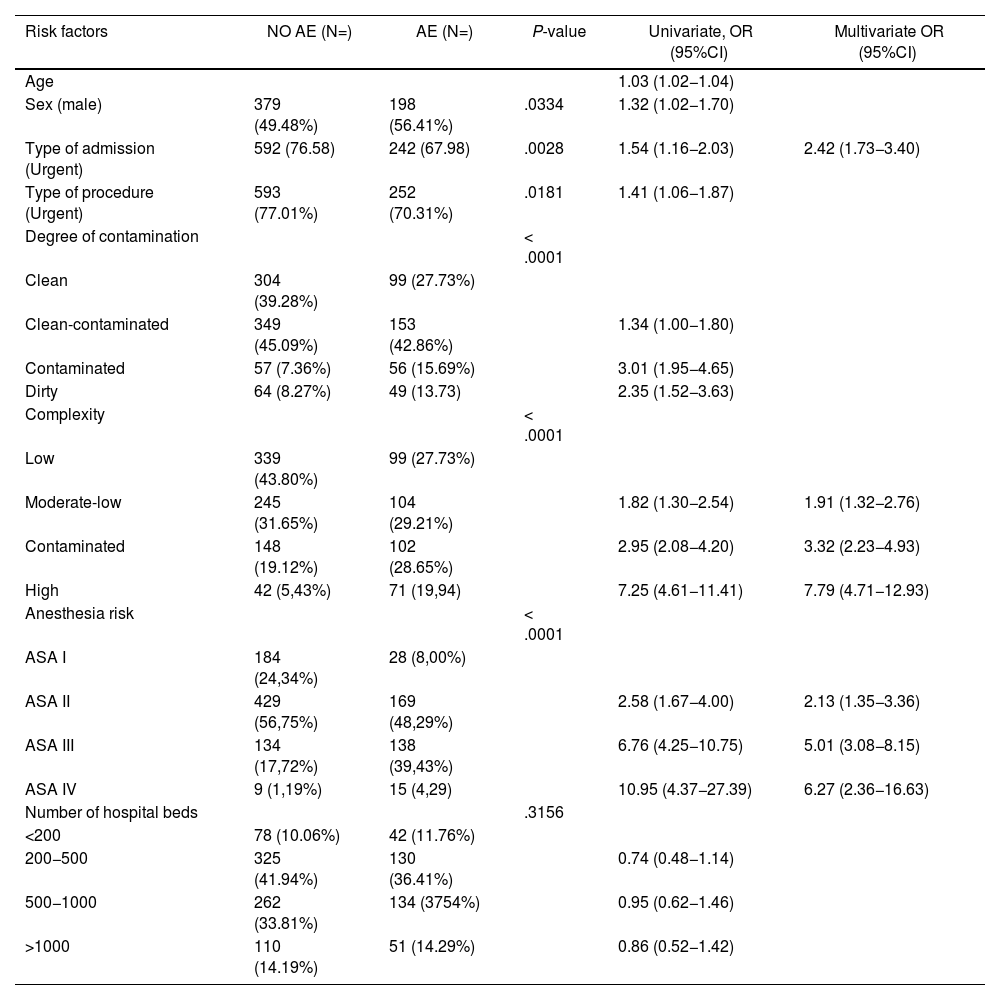

Patients with higher levels of ASA, greater complexity and urgent admission are factors associated with the presence of AE, having a high discriminatory power (area under the ROC curve = 0.741 [95%CI: 0.709−0.772]) and showing a sensitivity of 68.39%, specificity of 67.24%, PPV of 48.97% and NPV of 82.23% (Table 3).

Correlation of possible risk factors with AE.

| Risk factors | NO AE (N=) | AE (N=) | P-value | Univariate, OR (95%CI) | Multivariate OR (95%CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1.03 (1.02−1.04) | ||||

| Sex (male) | 379 (49.48%) | 198 (56.41%) | .0334 | 1.32 (1.02−1.70) | |

| Type of admission (Urgent) | 592 (76.58) | 242 (67.98) | .0028 | 1.54 (1.16−2.03) | 2.42 (1.73−3.40) |

| Type of procedure (Urgent) | 593 (77.01%) | 252 (70.31%) | .0181 | 1.41 (1.06−1.87) | |

| Degree of contamination | < .0001 | ||||

| Clean | 304 (39.28%) | 99 (27.73%) | |||

| Clean-contaminated | 349 (45.09%) | 153 (42.86%) | 1.34 (1.00−1.80) | ||

| Contaminated | 57 (7.36%) | 56 (15.69%) | 3.01 (1.95−4.65) | ||

| Dirty | 64 (8.27%) | 49 (13.73) | 2.35 (1.52−3.63) | ||

| Complexity | < .0001 | ||||

| Low | 339 (43.80%) | 99 (27.73%) | |||

| Moderate-low | 245 (31.65%) | 104 (29.21%) | 1.82 (1.30−2.54) | 1.91 (1.32−2.76) | |

| Contaminated | 148 (19.12%) | 102 (28.65%) | 2.95 (2.08−4.20) | 3.32 (2.23−4.93) | |

| High | 42 (5,43%) | 71 (19,94) | 7.25 (4.61−11.41) | 7.79 (4.71−12.93) | |

| Anesthesia risk | < .0001 | ||||

| ASA I | 184 (24,34%) | 28 (8,00%) | |||

| ASA II | 429 (56,75%) | 169 (48,29%) | 2.58 (1.67−4.00) | 2.13 (1.35−3.36) | |

| ASA III | 134 (17,72%) | 138 (39,43%) | 6.76 (4.25−10.75) | 5.01 (3.08−8.15) | |

| ASA IV | 9 (1,19%) | 15 (4,29) | 10.95 (4.37−27.39) | 6.27 (2.36−16.63) | |

| Number of hospital beds | .3156 | ||||

| <200 | 78 (10.06%) | 42 (11.76%) | |||

| 200−500 | 325 (41.94%) | 130 (36.41%) | 0.74 (0.48−1.14) | ||

| 500−1000 | 262 (33.81%) | 134 (3754%) | 0.95 (0.62−1.46) | ||

| >1000 | 110 (14.19%) | 51 (14.29%) | 0.86 (0.52−1.42) |

Regarding the harm category, most patient records corresponded with harm category F, specifically 352 cases (58.76%) of the total. In total, there were 88 serious AE (harm category G, H, I), representing 14.69% of the total. It is important to highlight that there were 17 deaths (2.83%) reported amongst the serious AE cases (category I).

In terms of preventability, 34.22% of AE were considered preventable, and 25.54% were considered to have a low probability of preventability (score 3).

DiscussionLarge epidemiological studies from the USA,1 Australia,10 the United Kingdom,11 New Zealand,12 Canada13 and Spain14 estimate the frequency of AE occurrence between 4% and 17%, and approximately 50% are considered preventable. However, a systematic review carried out in Germany of studies from 1995 to 200715 reported an incidence between 0.1% and 65.3%.

The AE rate detected in our study was 31.53%, which is higher than rates described in AE studies16 but similar to that described in studies where the trigger methodology had been used with hospitalized patients (between 7% and 40%).17

A scoping review by Schwendibeen concluded that half of AE were considered preventable, compared to 34% in our study.18

Many studies agree that the most frequent AE are mild, but some 7% of AE have been reported to result in patient death.19

In our study, regarding the severity of AE, the most frequent category of harm was mild harm: F with 58%, followed by category E. These results coincide with those described in the literature.20,21

It must be remembered that surgical specialties are considered a high-risk environment for the development of AE. Our study can be compared to the highest rates of AE described in the literature. This can be explained by the fact that all patients in the study have undergone surgery.

The most frequent group of AE is the infectious type, with surgical wound infection being the most frequent within that group. The systematic review by Anderson et al.22 stated that 3.79% of cases presented AE associated with the surgical wound, determining that these are the most common amongst the preventable AE. In our study, the most frequent group of AE was the infectious type, representing 35% of AE. The most common AE was surgical wound infection (12.04%), followed by poor pain control (8.68%), intra-abdominal abscess (7.002%), paralytic ileus (7.002%) and anastomotic fistula (6.72%).

When estimating preventable AE, there is great agreement between the different studies, despite different systems being used to define said concept. The proportion of preventable AE is estimated to be close to 50%.

In our study, we observed a total of 599 AE in 357 patients out of the 1132 analyzed, and

34.22% were considered preventable. Up to 48.41% of AE were considered to have a minimal or low probability of being preventable, and 17.36% were considered unavoidable.

In studies of surgical patients, it is worth highlighting the results of the ENEAS study, which estimated that 36.5% of AE in surgery patients were preventable.23 In the Australian paper on surgical patients,24 47.6% of AE were considered highly preventable and 20.8% were considered unpreventable.

The national study by Legaristi25 concludes a preventability of 53.5% in surgical patients, and the American study by Healey26 reports 48.6% in the same group of patients.

The vast majority of studies agree that mild and moderate AE (categories E and F) represent the majority of AE, and severe or fatal AE are the least observed. Although this distribution is maintained in surgical patients, the percentage of serious AE is higher in surgical patients than in all patients.27

LimitationsThe following factors can be considered limitations of this study:

One of the limitations is that it is a retrospective study. Although prospective studies are generally less likely to lose information, it would have been unfeasible to carry out the study. Furthermore, studies for the detection of AE are retrospective.

Source of information: Medical records provide a good source of information about care episodes, but some events may have been omitted. For this reason, we also analyzed both medical and nursing reports, ICU reports, laboratory tests and pharmacological prescriptions. However, the systematic and sequential review of the different documents specified in the project requirements makes the loss of relevant data unlikely.

Convenience Sampling: Although random sampling of services may have been considered ideal, it was deemed highly impractical because the departments were required to do time-consuming data collection work. In addition, the participation of a considerable number of services and their distribution amongst hospitals of varying complexities are factors that make our study representative of what happens in GGIS services across our country.

Large number of reviewers: The fact that there was a considerable number of reviewers could have been the reason for a lack of uniformity in the collection of information. However, the preparation of a detailed, practical manual addressing all aspects of the study, as well as the tutorial video providing examples based on electronic health records and the easy access to the review team, all minimize this possibility. In addition, universally accepted concepts were used, such as the definition of AE established by the WHO. The document delivered to the reviewers specified definition criteria based on the category of harm, preventability and complexity of the procedures, among other concepts, to standardize the results.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of AE in GGIS patients is high.

Patients with higher levels of ASA, more complex interventions and an emergency department admission are factors associated with the presence of AE.

Most AE were infectious. The most common AE was wound or surgical site infection.

Most of the AE detected have caused mild or moderate harm to patients.

About one-third of AE were preventable.

FundingResearch funders: European funds for regional development (FIS grant). Grant/contract number PI1701374.

Conflict of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz-López PM, Fuente-Bartolomé M, Pérez-Zapata AI, Rodríguez-Cuéllar E, Martín-Arriscado-Arroba C, Nogueras MG, et al. Análisis de eventos adversos en servicios de cirugía general y aparato digestivo. Estudio multicéntrico. Cir Esp. 2024;102:76–83.