While haemorrhoidal dearterialization and mucopexy are accepted as a valid alternative to haemorrhoidectomy, differences exist regarding the fixed or variable location of the arteries to be ligated. Our aim was to shed light on this issue of arterial distribution in candidates for surgery.

MethodsThe study included consecutive patients diagnosed with Goligher grade III and IV haemorrhoids, who had undergone Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation (DG-HAL) and rectoanal repair (RAR) at 2 medical centres in Spain. The main objective was to evaluate the number and 12-h clock locations of arterial ligatures necessary to achieve Doppler silence.

ResultsIn total, 146 patients were included: 111 (76%) men, and 35 (24%) women. Average age was 54 years (21–84). Grade III and grade IV haemorrhoids were diagnosed in 106 (72.6%) and 40 (27.4%) patients, respectively. The average number of ligatures per patient was 7 (range 2–12).

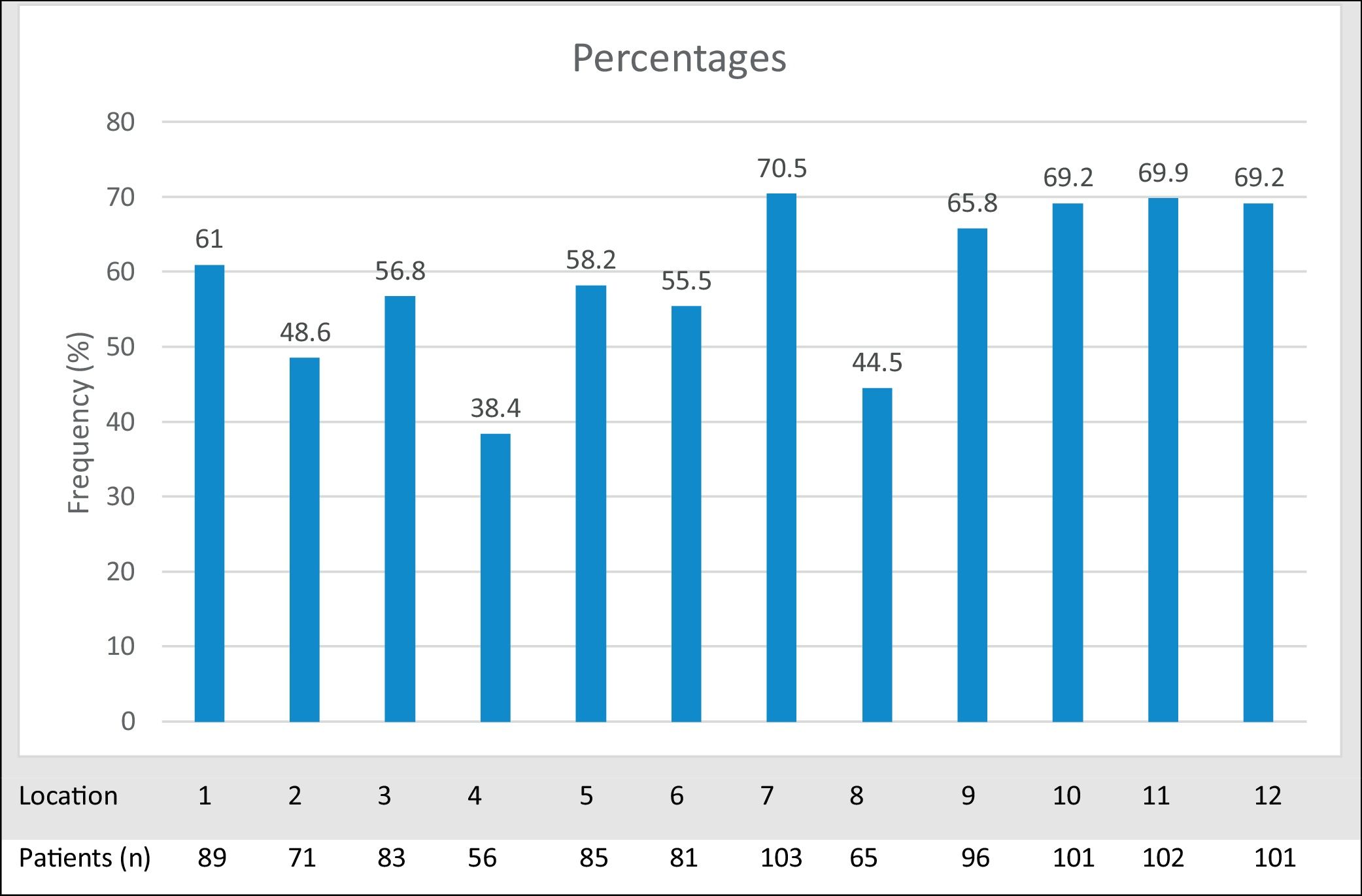

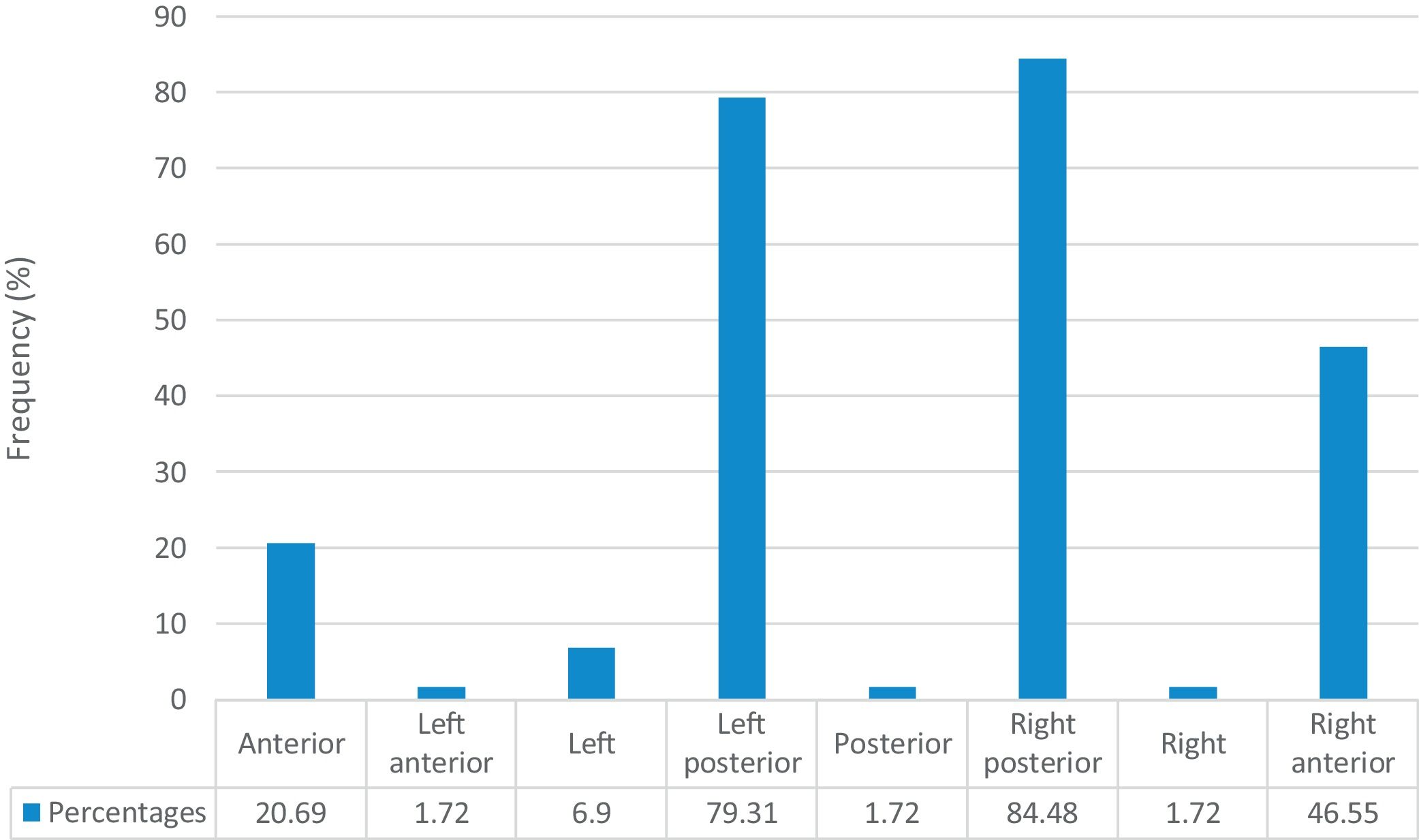

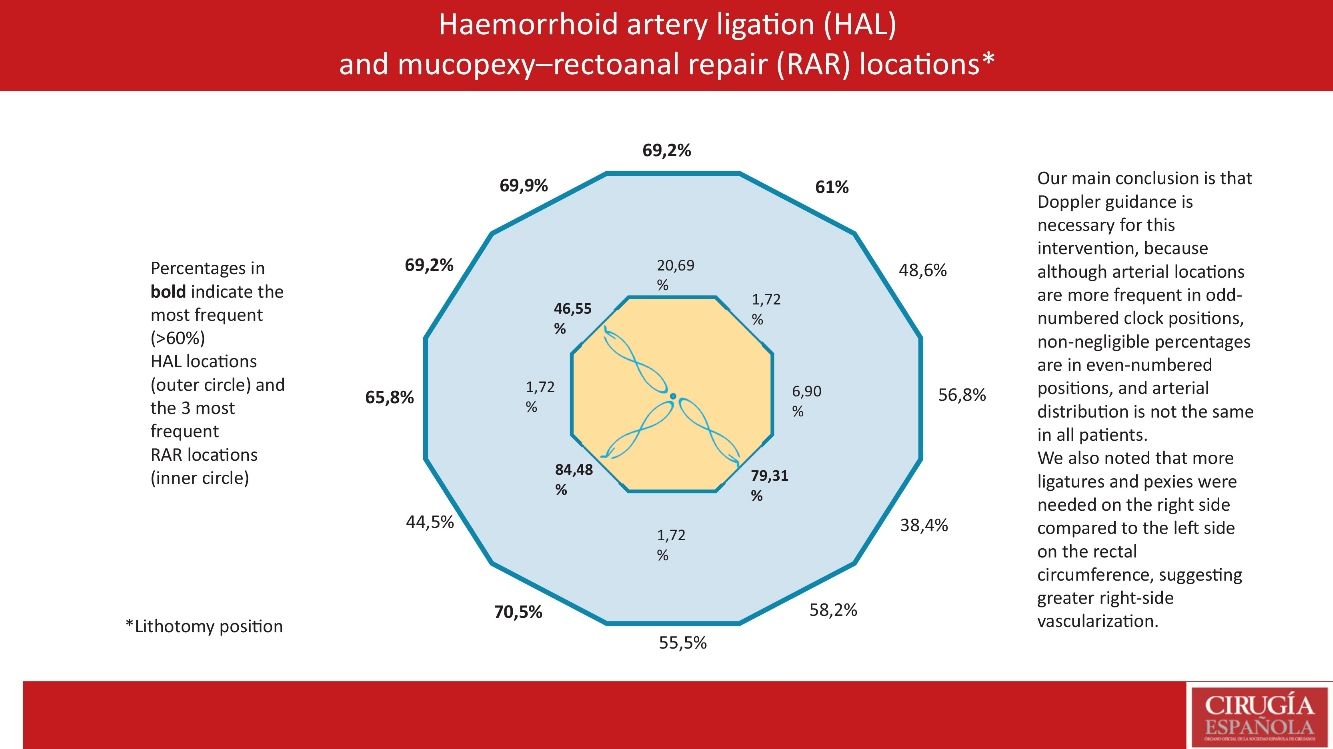

Ligature percentages greater than 60% occurred at clock positions 7, 11, 10, 12, 9, and 1. The average number of mucopexies per patient was 3 (range 1–4). The most frequent mucopexy locations were the left posterior, right posterior, and right anterior octants.

ConclusionsWhile the greatest frequency of arterial ligatures occurred in odd-numbered clock positions, non-negligible percentages occurred in even-numbered clock positions, which, in our opinion, makes the use of Doppler necessary, given that arterial distribution is not the same in all patients. We also noted that more ligatures and mucopexies were needed on the right half of the rectal circumference than on the left side, suggesting greater right-side vascularization.

Aunque la desarterialización hemorroidal y mucopexia es técnica aceptada como alternativa válida a la hemorroidectomía, existen divergencias en lo que se refiere a una localización fija o variable de las arterias a ligar. Nuestro objetivo ha sido arrojar luz sobre esta cuestionada distribución arterial en pacientes quirúrgicos.

MétodosSe han incluido consecutivamente pacientes con diagnóstico de hemorroides de III y IV grado operados mediante desarterialización hemorroidal guiada por Doppler (D-HAL) y reparación rectoanal (RAR) en dos centros hospitalarios españoles. El principal objetivo fue evaluar el número necesario de ligaduras arteriales y su localización horaria para conseguir un silencio Doppler.

ResultadosSe han incluido consecutivamente 146 pacientes, 111 (76%) varones y 35 (24%) mujeres, con una media de edad de 54 años (21–84), 106 (73%) fueron diagnosticados como grado III y 40 (27%) como grado IV. La media de ligaduras por paciente fue de 7 (2–12). Se encontraron porcentajes de ligaduras superiores al 60% en las posiciones horarias 7, 11, 10, 12, 9 y 1. La media de mucopexias por paciente fue 3 (1–4), siendo las localizaciones más frecuentes los octantes posterior izquierdo, posterior derecho y anterior derecho.

ConclusionesAunque los puntos horarios impares son los de mayor frecuencia de localización arterial, porcentajes no despreciables de localización ocurren en las posiciones pares lo que, en nuestra opinión, hace que el uso del Doppler sea necesario dado que la distribución arterial no es constante en todos los pacientes. Hemos podido constatar también que en la semicircunferencia derecha han sido necesarias más ligaduras y pexias que en el lado izquierdo, lo que sugiere una mayor vascularización derecha.

Although the gold standard for advanced haemorrhoidal disease (Goligher grades III-IV) is still resective surgery,1 there currently seems to be a trend — based on a different aetiopathogenic orientation — towards less invasive surgical treatment, which results in a shorter hospital stay and a faster return to normal life.2 The aetiopathogenesis of haemorrhoidal disease is much debated, as different factors are involved. However, the theory based on increased arterial flow vascularizing the haemorrhoidal piles is plausible. Haemorrhoids are sinusoids (ie, structures with no vascular wall), and there is no anal canal capillarity between arteries and veins. Hence, increased blood flow leads to hyperplasia of the corpus cavernosum recti, increasing the size and posterior descent of the haemorrhoidal plexus.3 In recent decades, this aetiopathogenic theory has resulted in the development of different techniques and devices for the surgical treatment of advanced haemorrhoidal disease.4

Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal artery ligation (DG-HAL) and Rectoanal repair (RAR) with personalised mucopexy have been increasingly used as an alternative to haemorrhoidectomy.5–8

However, there is no consensus as to whether Doppler use contributes significantly to satisfactory outcomes,4,9 and the existence of a fixed location of the distal branches of the superior rectal artery is similarly debated.10–12

This study aims to shed light on arterial distribution in patients with Goligher grade III-IV haemorrhoids treated with third-generation HAL + RAR.

MethodsPatientsOur study included consecutive patients operated on at 2 medical centres in Spain between 6 June 2016 and 29 November 2022. Inclusion criteria were Goligher grade III haemorrhoidal disease and Goligher grade IV haemorrhoidal disease with no circumferential or reducible prolapse. Exclusion criteria were inflammatory bowel disease, previous anal surgery, and current associated proctological pathology. Before the procedure, all patients signed an informed consent document pursuant to recommendations of the Ethics Committee of our Hospital. The procedure was performed in accordance with state-of-the-art and ethical standards.

Objectives and methodsThe main objective was to evaluate the number and location in 12-h clock positions of arterial ligatures necessary to achieve Doppler silence. A secondary objective was to evaluate the number and location of mucopexies in the prolapsing haemorrhoids, dividing the rectal circumference into octants (8 equal parts). Incidents and postoperative complications were also evaluated after one and 4 weeks.

Data were prospectively included in a spreadsheet (Microsoft Excel) consisting of 93 fields. Given the objectives of this particular study, data from only the following fields were analysed: demographic data, haemorrhoid grade, symptoms, surgery duration, number and location of arterial ligatures, number and location of mucopexies, anaesthesia type, hospital stay, and incidents or postoperative complications after one and 4 weeks. Office follow-up visits were scheduled on days 7–9 and 4 weeks after surgery. Postoperative pain was measured during in-person interviews, using a visual analogue scale (VAS), recording average defecation pain and resting pain. Postoperative pain treatment was paracetamol 1 g/8 h, alternating with dexketoprofen 25 mg/8 h for the first 3 days, follows by analgesia on demand after day 4. If pain was severe, tramadol 50 mg/8 h was prescribed. Longer follow-up data on subsequent complications, recurrences, reinterventions, and patient satisfaction were outside the scope of this study.

Surgical techniqueSurgery was performed in 2 phases: DG-HAL (Doppler-guided haemorrhoidal dearterialisation), followed by RAR (mucopexy of prolapsing haemorrhoids). A HAL-RAR wireless system was used (Trilogy Wi-3; AMI Agency for Medical Innovations GmbH, Feldkirch, Austria), consisting of a self-illuminatingproctoscope fitted with a Doppler transducer (ultrasonic frequency 8.2 MHz).

With the patient in the lithotomy position, the proctoscope was inserted in the distal rectum and gradually rotated 360 degrees clockwise to detect haemorrhoidal arteries. Each detected artery was ligated through the proctoscope window (above the Doppler transducer) using specifically designed 2/0 polyglycolic acid sutures (AMI Suture AHAL70) fitted to an FR 27 5/8 circle needle with a tapered round point. The HAL procedure terminated once Doppler silence was achieved. RAR was performed only on prolapsing haemorrhoids identified before and during surgery. Ligature locations were recorded as 12-h clock positions on a chart, with position number 6 placed on the posterior medial line. Mucopexies were located on a sphere divided into octants.

Statistical analysisQualitative data were recorded as absolute and percentage frequencies, and quantitative data as means with their standard deviation (SD) and as outliers. Differences between locations were evaluated using the paired Student t-test and non-paired signed-rank test pursuant to the Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS v9.4 software (SAS Inst., Cary, NC, USA).

ResultsA total of 146 patients were included in the study, with a mean age of 54 years (range 21–84); 111 (76%) were men and 35 (24%) women. Grades III and IV haemorrhoids were diagnosed in 106 (73%) and 40 (27%) patients, respectively. Reasons for surgical intervention were haemorrhoidal prolapse (observed in all patients; 100%), and bleeding (observed in 127 patients; 87%). Pain and obstructed defecation were reported by 28 (19%) and 35 (24%) patients, respectively. Spinal anaesthesia was administered to 56 patients (38%) and general anaesthesia (laryngeal mask) to 90 patients (62%). Average surgery time was 40 min (range 25–70). Outpatient surgery was performed in 90 patients (62%). The remaining

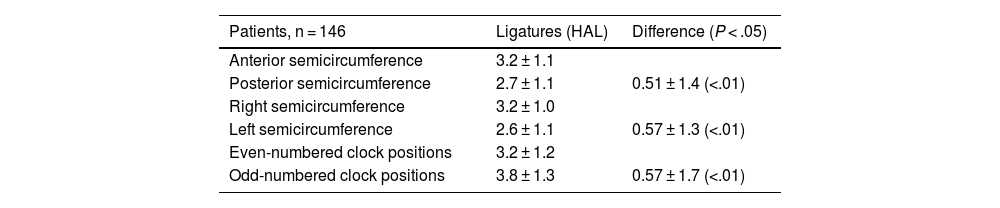

56 patients (38%) were hospitalised overnight: 17 who did not meet the criteria for outpatient surgery, and 39 who refused same-day discharge. Regarding the main objective (number and location in 12-h clock positions of arterial ligatures), data were obtained for all 146 patients. An average of 7 ligatures (range 2–12) were performed per patient. Arterial ligation percentages greater than 60% were observed for the following clock positions (Fig. 1): 7 (70.5%), 11 (69.9%), 10 (69.2%), 12 (69.2%), 9 (65.8%), and 1 (61%). The average number of arterial ligatures in odd-numbered clock positions was significantly higher than in even-numbered clock positions. On dividing the rectal circumference according to the 12-h clock into anterior (positions 10, 11, 12, 1, and 2) and posterior (positions 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8) halves, and right (positions 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11) and left (positions 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5) halves, significantly higher numbers of ligatures were found in the anterior half versus the posterior half, and in the right half versus the left half. Table 1 reports mean ± SD locations of the arterial ligatures.

Haemorrhoid artery ligation (HAL) locations (mean ± SD).

| Patients, n = 146 | Ligatures (HAL) | Difference (P < .05) |

|---|---|---|

| Anterior semicircumference | 3.2 ± 1.1 | |

| Posterior semicircumference | 2.7 ± 1.1 | 0.51 ± 1.4 (<.01) |

| Right semicircumference | 3.2 ± 1.0 | |

| Left semicircumference | 2.6 ± 1.1 | 0.57 ± 1.3 (<.01) |

| Even-numbered clock positions | 3.2 ± 1.2 | |

| Odd-numbered clock positions | 3.8 ± 1.3 | 0.57 ± 1.7 (<.01) |

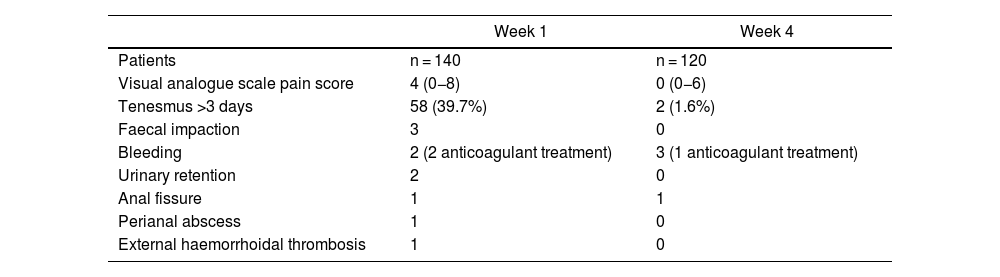

Regarding our second objective (number and location of mucopexies), data were obtained from 59 patients, who underwent an average of 3 mucopexies (range 1–4) per patient. The most frequent mucopexy locations were the right posterior (84.5%), left posterior (79.3%), and right anterior (46.6%) octants (Fig. 2). Table 2 summarises week one and week 4 follow-up complications. After one week and 4 weeks, 6 patients and 26 patients were lost to follow-up, respectively. Average VAS pain score was 4 at week one, and no pain was reported at week 4. While rectal tenesmus of more than 3 days was observed in 39.7% of the patients, by week 4 it was only reported by 2 patients, and then only as an occasional occurrence. Enemas were required by 3 patients due to faecal impaction during week one. Bleeding occurred during week one in 2 patients, both of whom were receiving anticoagulant treatment (factor Xa inhibitors), and then during week 2 in 3 more patients, one of whom was being treated with acenocoumarol. All patients receiving anticoagulant treatment were switched to low-molecular-weight heparin 3 days before surgery, and none required further surgery. A patient with no coagulation problems who bled in week 2 required surgical haemostasis.

Haemorrhoid artery ligation (HAL) and rectoanal repair (RAR) complications.

| Week 1 | Week 4 | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients | n = 140 | n = 120 |

| Visual analogue scale pain score | 4 (0−8) | 0 (0−6) |

| Tenesmus >3 days | 58 (39.7%) | 2 (1.6%) |

| Faecal impaction | 3 | 0 |

| Bleeding | 2 (2 anticoagulant treatment) | 3 (1 anticoagulant treatment) |

| Urinary retention | 2 | 0 |

| Anal fissure | 1 | 1 |

| Perianal abscess | 1 | 0 |

| External haemorrhoidal thrombosis | 1 | 0 |

Acute urinary retention in 2 patients required catheterisation, anal fissures in another 2 patients required no surgical intervention, one patient with perianal abscess in week one required drainage, and external haemorrhoidal thrombosis in one patient resolved spontaneously.

DiscussionAnatomical studies performed on cadavers have investigated vascularisation of the distal rectum,10,13 while in vivo studies provide information on the number and distribution of haemorrhoidal arteries in patients with haemorrhoidal disease, covering all or some of the Goligher grades.12,14

In our study, focused exclusively on patients with advanced haemorrhoidal disease (Goligher grades III-IV), we found an average of 7 arteries per patient. In relation to artery location, we observed divergences with other studies. We found ligation percentages greater than 60% in 6 clock positions (7, 11, 10, 12, 9, and 1), largely corroborating the Miyamoto et al. results,12 which reported 75.7% and 71.8% of locations in clock positions 7 and 11, respectively, compared to 70.5% and 69.9%, respectively, in our study. In the Trilling et al.14 series, the highest number of ligatures was found in clock positions 7, 5, 9, 3, and 2, and the lowest number in clock positions 6 and 12, which contrasted with our finding of clock positions 4 and 8 having the lowest arterial ligature percentages.

When we analysed rectal circumference halves, significantly more ligatures were placed in the anterior half than in the posterior half, and likewise, on the right side than on the left side. We also observed more arterial ligations in odd-numbered clock positions, broadly corroborating other studies3,15,16 and seemingly confirming a greater frequency of arteries located in odd-numbered clock positions.

Those findings may suggest that placing ligatures only in odd-numbered clock positions may be adequate treatment for haemorrhoidal disease, thereby obviating Doppler use. Nonetheless, Avital et al.11 reported that if Doppler had not been used, at least 1 artery would have gone undetected in 29% of their patients; in our study, non-negligible percentages in even-numbered clock positions would have gone undetected without the use of Doppler. We suggest, therefore, that a higher rate of arterial locations in odd-numbered clock positions does not justify abandoning Doppler use. Given the different methodological and inclusion criteria among studies comparing short- and medium-term clinical results with and without Doppler,17,18 it is difficult to arrive at any conclusive opinion. Therefore, establishing whether complete dearterialization is necessary — for which Doppler use is necessary — requires more comparable studies reporting longer-term results (more than 5 years).

In agreement with other authors,4 we believe that mucopexies should be personalised and should not follow a fixed pattern in terms of number or location. Regarding the second objective of this study, which was to identify mucopexy location, and considering that pexies are only performed on prolapsing piles, the 3 main locations were found to be the right posterior, left posterior, and right anterior octants. Those locations are quite close to the locations reported to be most frequent in haemorrhoidectomy, specifically clock positions 11, 7, and 3, bearing in mind that our left-side mucopexy was actually posterior left rather than purely left at 3 o’clock. It was difficult to establish a location and frequency correlation between arterial ligatures and mucopexies. Note, however, that more ligations and pexies were performed on the right half of the rectal circumference than on the left half. The anatomical study by Aigner et al.13 shows that, while the right branch of the superior rectal artery is divided into anterior and posterior branches, the left branch remains on the left side; furthermore, there is no fixed location for the subsequent division into different haemorrhoidal arteries that vascularise the haemorrhoidal plexus. Our results suggest that the right half may be more vascularised than the left half, a distinction that has also been noted by Miyamoto et al.12 and Trilling et al.14 Increased blood flow as an aetiopathogenic factor in haemorrhoidal disease, together with greater right-side vascularisation, may explain the higher rate of haemorrhoidal prolapse found on the right half of the rectal circumference.

No incidents occurred with the Trilogy device, whose compact and wireless design greatly improved ergonomics. As for complications directly related to the technique at week one and week 4, while dearterialisation as an alternative to haemorrhoidectomy first raised interest because it reduced postoperative pain, the subsequent inclusion of mucopexy means that the technique is not painless. In our study, an average VAS-scored pain level of 4 during week one was reported by patients during in-person interviews. Interviewing is important, since patients may confuse somatic pain with tenesmus, which is visceral. Note that all patients had been preoperatively informed of the possibility of postoperative rectal tenesmus in week one. Rectal tenesmus is undoubtedly the main disadvantage of this technique, as also commented by Sobrado et al.6 While around 40% of our patients experienced rectal tenesmus for more than 3 days, this symptom had almost completely resolved by week 4. Our rate of rectal tenesmus was higher than reported in the literature (10%–24%)18 and can only be explained by the difficulties of assessing a symptom as subjective as the sensation of a full rectum.

No serious complications were detected in the immediate postoperative period. One patient required a second operation due to bleeding, and another patient required debridement of a perianal abscess. All other complications were resolved with medical treatment. As regards the technique, 2 of our patients developed anal fissures in locations that coincided with a mucopexy that was probably too low. We consider this a technical error that should obviously be avoided. The 2 patients, who had no sphincter spasms, were successfully treated topically (0.75% hyaluronic acid rectal ointment + 3% vitamin E).

ConclusionsOur main conclusion is that Doppler guidance is necessary for this intervention. Although arterial locations are more frequent in odd-numbered clock positions, non-negligible percentages are located in even-numbered positions, and arterial distribution is not the same in all patients. We also noted that more ligatures and mucopexies were needed on the right side compared to the left side of the rectal circumference, suggesting greater right-side vascularisation. However, larger studies are needed to confirm this asymmetry in the distribution of the terminal branches of the superior rectal artery.

Author contributionsAll authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Dr. Puigdollers, Dr. De Balle and Dr. Rovira-Argelagues. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Dr. Puigdollers, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no competing interests to declare that are relevant to the content of this article. Dr. Puigdollers has participated in five surgical workshops proctoring the HAL-RAR technique with the third-generation wireless Trilogy system for which he received no remuneration.

FundingA.M.I. Agency for Medical Innovations (Im Letten 1, 6800 Feldkirch, Austria) has provided funding for statistical analysis and assistance with the English version of the manuscript, as well as for data collection from medical records.

Data availabilityAll data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. The data are published in literature as shown in the reference list. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

The authors thank Juan F. Dorado (PeRTICA) for assistance with the statistical analysis and Ailish Maher for assistance with the English in a version of this article.

Please cite this article as: Puigdollers A, de Balle M, Rovira-Argelagues M. Distribución de las arterías hemorroidales en pacientes con hemorroides de grado III y IV tratados mediante ligadura arterial y reparación rectoanal. Evaluación del guiado Doppler. Cir Esp. 2024;102:69–75.