Conservative breast cancer surgery is facing a new problem: the potential tumour involvement of resection margins. This eventuality has been closely and negatively associated with disease-free survival. Various factors may influence the likelihood of margins being affected, mostly related to the characteristics of the tumour, patient or surgical technique. In the last decade, many studies have attempted to find predictive factors for margin involvement. However, it is currently the new techniques used in the study of margins and tumour localisation that are significantly reducing reoperations in conservative breast cancer surgery.

La cirugía conservadora del cáncer de mama plantea un nuevo problema: la posible afectación tumoral de los márgenes de resección. Esta eventualidad se relaciona de forma negativa con la supervivencia libre de enfermedad. Diversos factores pueden incrementar la probabilidad de que los márgenes estén afectados, en su mayoría relacionados con características del tumor, de las pacientes o de la técnica quirúrgica. En la última década, muchos han sido los estudios que han tratado de identificar factores que puedan predecir la afectación de los márgenes quirúrgicos, aunque en la actualidad, son las nuevas técnicas utilizadas en el estudio de los márgenes y en la localización tumoral las que están propiciando una disminución significativa de las reintervenciones en la cirugía conservadora del cáncer de mama.

Breast cancer surgery has gradually evolved since its introduction to use increasingly conservative techniques, from the radical mastectomies described by Halsted in the early 20th century to the minimal lumpectomies performed today. However, this progress has led to a new problem: tumour involvement at the resection margin.

This possibility, which ranges between 20% and 40% for conservative surgery,1,2 favours local recurrence3–5 and, in most cases, requires reoperation with the extension of resection margins. This fact becomes more relevant in patients under 40 years of age, who have a lower rate of disease-free survival after ten years compared with older patients (34.6% vs 84.4%).6 In contrast, no differences have been found in patients with negative margins with regard to local recurrence in different age groups.7 While the importance of free margins is clear, other factors have been shown to be determinant in the probability of developing local recurrence. Systemic therapy is prominent among these factors, decreasing the rate of local recurrence. Tumour biology is another important factor, as in the case of tumours classified as “triple negative” (negative for progesterone, oestrogen, and HER2 receptors), which have an increased risk of local recurrence, regardless of treatment.8

On the other hand, the influence of resection margins around the tumour (defined in many centres as a distance between 0 and 2mm) on local recurrence is a controversial issue.5,9,10 However, most studies that have evaluated this issue have concluded that there is no correlation between local recurrence and tumour distance to resection margins, so that at present, the presence of close margins is not an indication for reoperation. In this regard, it is important to note that negative margins, whatever their size, might not be indicative of the absence of residual breast cancer, but would only point to a remaining tumour burden low enough to be controlled by radiotherapy.8 This assertion was demonstrated in a study of 1985 that concluded that up to 43% of patients had some type of satellite tumour nodule at a distance beyond 2cm from the main tumour, and this figure decreased to 11%–18% if the margin measured 3–4cm.11

Despite the undeniable importance of free margins in disease progression, at least half of patients undergoing reoperation will not present residual tumour (RT), which makes these surgeries avoidable and potentially unnecessary.12 Therefore, over the last decade, many studies have aimed to find predictors of positive margins (PM) and RT, and most of them agree on a number of factors that should be taken into account in the design of the surgical strategy. At the same time, several techniques and protocols for tumour localisation and assessment of the resection margins are being developed to decrease the rates of PM and RT.

The aim of this review is to analyse the available scientific evidence on the biological and technical factors associated with negative resection margins and no residual tumour to achieve the most conservative surgery possible for breast cancer.

Predictors of Positive Margins in the Surgical SpecimenAs discussed above, the involvement of the resection margins has been identified as an important risk factor for local recurrence,3 so that in most centres, the term “positive margins” is synonymous with reoperation, causing a resultant negative impact from the aesthetic and economic viewpoints, causing a delay in adjuvant therapy, and generating patient anxiety.

A number of mostly retrospective studies published during the last decade have identified specific factors that independently predict a greater risk of PM. These factors are as follows: young patients (<45–50 years old),13–15 large tumours (>20–30mm),15–21 multifocal tumours,15–17,20,21 the absence of a preoperative cancer diagnosis,13,17,18,21,22 microcalcifications on mammography,15,16 stereotaxic tumour localisation,23–27 the presence of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS),13,15,18,20,21 and lobular infiltration in histology studies.13,18–20,22

Recently, a prospective study was published in 2012 including 305 patients with non-palpable breast cancer who underwent conservative surgery.2 The results of the study, in accordance with the studies cited above, support the conclusion that the presence of microcalcifications, multifocal disease, stereotaxic tumour localisation (vs ultrasound), and the presence of DCIS are risk factors in both univariate and multivariate analyses; stereotaxic localisation vs ultrasound had a higher odds ratio on multivariate analysis, this difference was most likely related to the fact that tumours that are only observed by mammography are diffuse and less well-defined, making their detection and resection more challenging.

Another recent prospective study sought to identify preoperative factors that were useful in assessing the risk of requiring multiple operations compared with a single operation after lumpectomy.28 The results of the study, in univariate and multivariate analysis, agreed with the above-mentioned studies with regard to microcalcifications and lobular histology, which increased the risk of reoperation for positive margins. Another finding of that study (not previously described) was that grade 2 on the preoperative biopsy (moderately differentiated tumour) almost doubled the risk of reoperation compared with grade 1 (well-differentiated tumour), but there was no significant difference with grade 3 (poorly differentiated tumour), which had been found in another study.29

Shin et al.,30 also in 2012, showed that patients with radiographically dense breasts (>75% fibroglandular tissue) had a positive margin rate four times higher than patients with fatty breasts, which was most likely due to the difficulty of defining the tumour boundaries, a finding that was also demonstrated by Bani et al.31 This risk factor, along with the other four (DCIS, lobular histology, microcalcifications and tumour size difference >5mm between ultrasound and NMR), allowed the authors to develop a risk nomogram that led to the detection of up to 85% of patients with PM; this nomogram could be very useful in the preoperative identification of patients with significant risk of PM, allowing the patient's physicians to use the most appropriate therapeutic strategy for achieving negative resection margins.

Finally, it has also been proposed that preoperative chemotherapy and formalin fixation as well as the length of time from specimen removal to pathological analysis could determine an insufficient pathological assessment of the state of the margins and consequently give a higher rate of positive margins due to tissue shrinkage. The first of these factors has not been confirmed; in this regard, Soucy et al.32 found no significant differences in margin involvement between patients with and without preoperative chemotherapy. With regard to the remaining two factors, a study that analysed the weights and volumes as well as the distances between the margins and the tumour for 68 specimens after different periods of time concluded that there was no relationship with time or formalin fixation.33 However, this last fact is controversial, and studies have been published that appear to show reduced tumour size after formalin fixation.34 In addition, an experimental study published in 2010 that used MRI to compare the effect of formalin on different tissues concluded that this aldehyde causes a slight expansion of muscle tissue, fatty tissue retraction, and specimen flattening.35 With this data in view, it can be concluded at least that formalin fixation of the specimen could somehow alter the measurement of the tumour margins, but only future studies will clarify the importance of this fact.

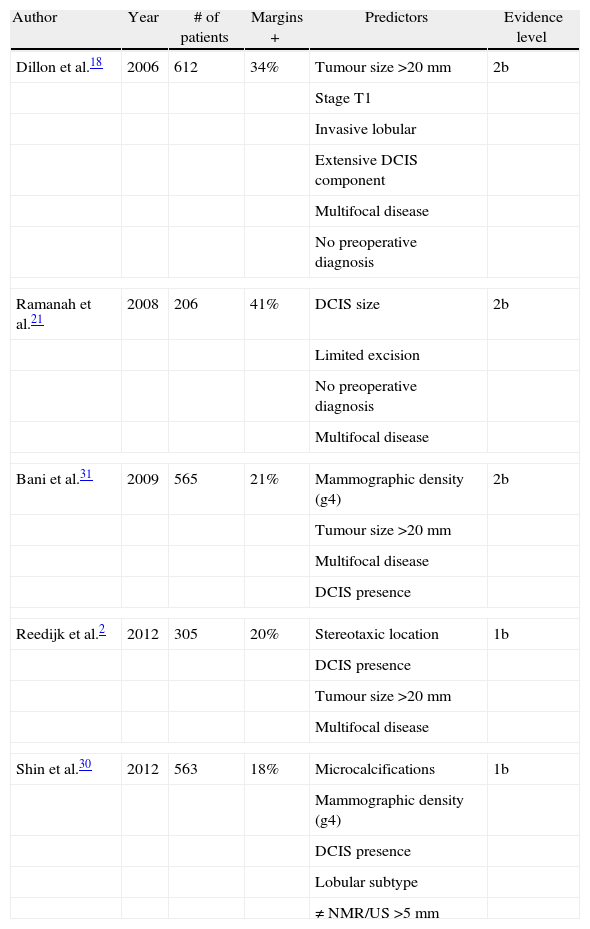

Schematically, Table 1 shows the main features and findings of the studies discussed in this section.

Predictors of Positive Margins in the Surgical Specimen.

| Author | Year | # of patients | Margins + | Predictors | Evidence level |

| Dillon et al.18 | 2006 | 612 | 34% | Tumour size >20mm | 2b |

| Stage T1 | |||||

| Invasive lobular | |||||

| Extensive DCIS component | |||||

| Multifocal disease | |||||

| No preoperative diagnosis | |||||

| Ramanah et al.21 | 2008 | 206 | 41% | DCIS size | 2b |

| Limited excision | |||||

| No preoperative diagnosis | |||||

| Multifocal disease | |||||

| Bani et al.31 | 2009 | 565 | 21% | Mammographic density (g4) | 2b |

| Tumour size >20mm | |||||

| Multifocal disease | |||||

| DCIS presence | |||||

| Reedijk et al.2 | 2012 | 305 | 20% | Stereotaxic location | 1b |

| DCIS presence | |||||

| Tumour size >20mm | |||||

| Multifocal disease | |||||

| Shin et al.30 | 2012 | 563 | 18% | Microcalcifications | 1b |

| Mammographic density (g4) | |||||

| DCIS presence | |||||

| Lobular subtype | |||||

| ≠ NMR/US >5mm | |||||

DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; US: ultrasound; g4: grade 4; Margins +: Margin positivity (%): NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance, NMR/US: tumour measurement difference between ultrasound and NMR.

Classification of the level of evidence according to The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence, Levels of Evidence Working Group, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM).

In our experience, up to 60% of female patients who undergo reoperation due to PM show no RT on the final histopathology. This finding is consistently described in the literature using percentages of approximately 50% in most studies.36,60 Thus, knowing how to predict which patients will not present residual tumour at reoperation would be very beneficial.

The first study was published in 1995, and the presence of RT was retrospectively studied in patients who had previously undergone excisional biopsy due to breast cancer.37 After reviewing 420 patients, of whom only 47% had RT, the authors concluded that the most significant risk factors in this regard were clinical presentation (palpable vs non-palpable) with 3% vs 11% and axillary status (metastatic vs free) with 14% vs 7%. On the other hand, Saarela et al.,38 after prospectively analysing 49 patients, found that tumour size was not related to the presence of RT, although the authors understandably found a relationship with multifocality, similar to other authors.39 However, those two studies are not comparable because of the size of the sample and because the latter only included patients with non-palpable tumours. Moreover, another study in 2004 determined that in tumours ≥20mm with PM, RT is present up to 14% more frequently than in smaller tumours.40 Another prospective study conducted with 47 patients41 supported this finding, establishing the cut-off point for tumour size at 30mm. This cut-off, coupled with the presence of HER2/neu+ as a risk factor, has also been described for PM,42 and a relationship between tumour volume and surgical resection specimen greater than 70% is known. In that study,41 nine other parameters were studied without finding statistical significance, including an extensive intraductal component, palpable tumours, and axillary lymph node metastases.

In 2009, a surprising study concluded after retrospectively analysing 303 patients that the RT rate did not differ between patients with close/positive margins.39 These unexpected data are in disagreement with another methodologically similar study, which concluded that there was a lower rate of residual tumour involvement with greater margins.43

In 2012, Halevy et al.29 developed a probability score for finding RT at reoperation after PM based on six parameters that behaved as independent risk factors, concluding that, for patients with margins ≤2mm and a score <4, the probability of finding a site of residual microinvasive tumour (<2mm) was 3.2%, with up to a 10% probability of finding DCIS.

To summarise, Table 2 shows the results of the main studies cited in this section.

Predictors of Residual Tumour at Reoperation.

| Author | Year | # of patients | Residual tumour + | Predictors | Evidence level |

| Jardines et al.37 | 1995 | 420 | 47% | Tumour size >20mm | 2b |

| Positive axillary lymph nodes | |||||

| Palpable tumour | |||||

| Infiltrating lobular histology | |||||

| Cellini et al.40 | 2004 | 276 | 63% | Tumour size >20mm | 2b |

| G2 or G3 tumour | |||||

| Positive vs close margin | |||||

| More than one margin positive | |||||

| Kotwall et al.43 | 2007 | 582 | 30% | Palpable tumour | 2b |

| Large tumour | |||||

| Positive axillary lymph nodes | |||||

| Sabel et al.39 | 2009 | 303 | 33% | For DCIS: young age | 2b |

| For IC: multifocal disease | |||||

| Halevy et al.29 | 2012 | 293 | 38% | Age <50 years | 2b |

| Positive axillary lymph nodes | |||||

| Tumour size ≥30mm | |||||

| Multifocal disease | |||||

| Previous resection without harpoon | |||||

| Margin <1mm | |||||

| Atalay et al.41 | 2012 | 104 | 45% | Positive HER2 | 2b |

| Tumour volume/specimen >70% | |||||

DCIS: ductal carcinoma in situ; IC: infiltrating carcinoma; G2: moderately differentiated tumour; G3: poorly differentiated tumour.

Classification of the level of evidence according to The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence, Levels of Evidence Working Group, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM).

At least three other techniques have proven useful as alternatives to harpoon localisation in non-palpable tumours.

Intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS)-guided resection, which is based on tumour assessment before and during surgery and also on the resected specimen, has been shown to significantly reduce the rate of PM down to 3%–11%23,24,26,27 compared with the 45%–57% that has been described in some series with harpoon localisation and the 26% achieved by radio-guided occult lesion localisation (ROLL).24,44 While it is true that the IOUS data are inconclusive, a study in 2012 found similar rates of PM (6.7% vs 6.5%) and reoperations (12.5% vs 11%) between IOUS and harpoon techniques, respectively, favouring the use of the harpoon in disagreement with the majority of studies.45 However, given that ultrasound is not the ideal technique to evaluate microcalcifications (and thus DCIS) and that only 50% of tumours are observed on ultrasound,46 its use cannot be generalised. However, in view of these results, it may be useful in centres with availability and experience.47

Cryoprobe-assisted localisation (CAL) is also based on ultrasound and therefore has the same disadvantages. This technique, originally used for the treatment of benign tumours,48 was first applied in breast cancer in 2003 by Tafra et al.49 Its usefulness has been demonstrated in small, non-palpable tumours. In this technique, a cryoprobe guided by ultrasound is inserted into the tumour and freezes it, converting it into a palpable sphere that is easily resectable.36 While this technique has not been proven superior to the harpoon with regard to the rate of PM (28% vs 31%, P=.691) and reoperations (19% vs 21%, P=.764),50 it clearly decreases operating time and the volume of removed tissue, improving aesthetic results.50 Moreover, the procedure causes tumour necrosis per se and may therefore have an effect on margin ablation. In 2011, the first series to use this technique for the percutaneous ablation of tumours <10mm was published. The procedure showed complete tumour necrosis as assessed by MRI and histopathology in 14 of the 15 patients included in the study; its failure in the remaining patient was possibly due to an incorrect probe position.51

In contrast, based on nuclear medicine, the ROLL technique was described in 1996 as a tool for the localisation of palpable tumours.52 When compared with the harpoon, ROLL is safe, effective and less bloody53; it even, according to some authors, decreases the rate of PM (57% vs 26%)54 and reoperations.55,56 Moreover, ROLL does not increase operative time and even decreases tumour localisation time up to 7min in some series55–57; however, it does appear to increase costs compared with the harpoon.36 A meta-analysis published in 2012 including 4 studies and 449 patients supports these results.58

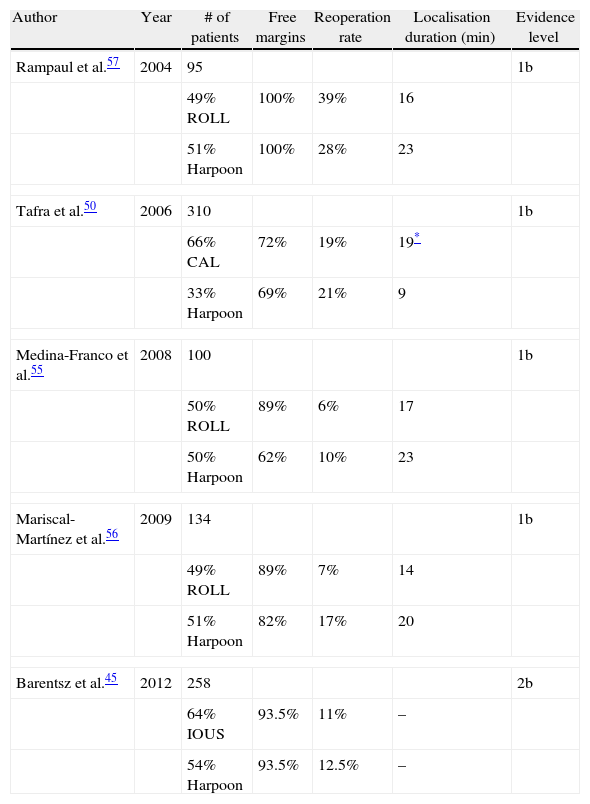

Table 3 shows a summary of the main studies conducted comparing ROLL, CAL and IOUS with the harpoon procedure.

Influence of Intraoperative Tumour Localisation Techniques.

| Author | Year | # of patients | Free margins | Reoperation rate | Localisation duration (min) | Evidence level |

| Rampaul et al.57 | 2004 | 95 | 1b | |||

| 49% ROLL | 100% | 39% | 16 | |||

| 51% Harpoon | 100% | 28% | 23 | |||

| Tafra et al.50 | 2006 | 310 | 1b | |||

| 66% CAL | 72% | 19% | 19* | |||

| 33% Harpoon | 69% | 21% | 9 | |||

| Medina-Franco et al.55 | 2008 | 100 | 1b | |||

| 50% ROLL | 89% | 6% | 17 | |||

| 50% Harpoon | 62% | 10% | 23 | |||

| Mariscal-Martínez et al.56 | 2009 | 134 | 1b | |||

| 49% ROLL | 89% | 7% | 14 | |||

| 51% Harpoon | 82% | 17% | 20 | |||

| Barentsz et al.45 | 2012 | 258 | 2b | |||

| 64% IOUS | 93.5% | 11% | – | |||

| 54% Harpoon | 93.5% | 12.5% | – | |||

CAL: cryoprobe-assisted localisation; IOUS: intraoperative ultrasound resection; ROLL: radio-guided occult lesion localisation.

Classification of the level of evidence according to The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence, Levels of Evidence Working Group, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM).

Several new techniques are emerging in the field of intraoperative tumour detection, but they are still far from becoming standardised.

The manufacture of manual positron detection probes such as positron emission tomography (PET), which are based on measuring cellular metabolic processes, has made the development of real-time tumour detection techniques possible.59 Preliminary results support the possible usefulness of this technique in breast cancer, although the lack of specificity and spatial resolution, the difficulty in detecting small tumours (<10mm) and its high cost make it a technique that still needs further development.6,36

Similarly, most likely the most innovative technical development in this regard is near-infrared fluorescence optical imaging. Based on the emission properties of certain fluorochromes for this frequency of light either after binding to tumour receptors such as VEGF, EGF2, or HER2/neu61–64 or by being activated by tumour proteases such as cathepsin B and D and matrix-2 metalloproteinase,65,66 this technique will allow tumour detection and evaluation and the excision of any remaining tumour tissue or suspicious lymph nodes.67 This technique is quick, secure, safe, easy to perform, relatively inexpensive and has a high resolution (up to 10μm). Despite all of these advantages, the depth at which breast tumours are often found is an obstacle due to the characteristics of light propagation in tissue. However, this technique is emerging as one of the most promising in the future of conservative breast cancer surgery.36 Other photoacoustic imaging devices that are still under investigation could also prove useful in the coming years.68

Study of Resection Margins: How, When and WhereThe simplest of all the methods used for the evaluation of resection margins is based on tumour boundary detection with India ink, macroscopic evaluation during surgery and microscopic study by the pathologist. However, new analysis techniques for tumour margins have greatly improved the results over India ink detection, rendering this technique obsolete.

Some of these techniques are performed by the radiologist on the surgical specimen or through the use of ultrasound or mammography. In this regard, a study conducted in 2006 with 25 samples concluded that the exclusive use of ultrasound provided better results in the assessment of margins than mammography, and similar results were obtained after combining both techniques. Ultrasound overestimated the margins in 58.9% of cases, while mammography overestimated the margins in 66.7%. In addition, the mean difference between the estimated minimum margin was 2.1mm by histology and ultrasound and 3.8mm by mammography, which was a statistically significant difference. Thus, the authors concluded that if the tumour margin measured by ultrasound was twice the desired amount (>4mm), the adequate margin rate would be exceeded in 90% of cases.69 Despite this finding, routine mammography itself in the absence of any other method, has proved useful in patients with non-palpable tumours,70 reducing the reoperation rate from 31% to 20%.71

From a histopathological point of view, there are several proven methods to assess resection margins intraoperatively.

Frozen section analysis (FSA) is an increasingly popular procedure in breast surgery. The specimen is frozen after resection and later processed and analysed microscopically (a process that takes approximately 30min). It has a sensitivity and specificity of 65%–78% and 98%–100%, respectively.36 The cost-benefit ratio of the technique is highly positive by reducing the number of reoperations,72,73 although it should be noted that it increases surgical time, can undermine a definitive histological analysis, and is unreliable both in tumours smaller than 10mm and in DCIS.74,75

Another promising technique in this field is intraoperative touch preparation cytology (IOTPC), or simply imprint cytology (IC). The basis of this technique, for which automated systems are being developed,76 is the ability of cancer cells to adhere to glass (which adipose and glandular tissues lack). This method has shown a sensitivity and specificity close to 100% in some studies77,78 and the ability to decrease local recurrence at 5 years compared with FSA (8.2% vs 2.8%).79 However, it appears to be less effective in lobular tumours,80 presenting artefacts with the use of electrocautery, and does not allow assessment of multifocality or the distance to the margins.36

A systematic review was recently published comparing both techniques (FSA vs IC) to determine their effectiveness in the evaluation of surgical margins and the consequent decrease in reoperations.81 In that paper, no large differences were found between the two techniques, except for execution time (13min for IC vs 26min for FSA). The sensitivities of FSA and IC were 83% and 72%, respectively, and the specificities were 95% and 97%, respectively. The reoperation rate without either technique was estimated at 35%, which fell to 11% with IC and 10% with FSA.

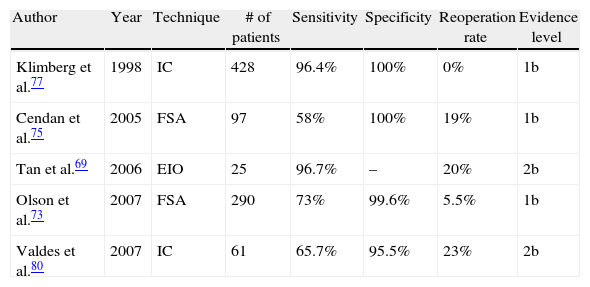

Table 4 shows the most relevant results of the most influential studies in this regard, although new randomised, controlled, prospective studies are needed to confirm these results and clarify the role of these techniques in the future.

Study of Resection Margins.

| Author | Year | Technique | # of patients | Sensitivity | Specificity | Reoperation rate | Evidence level |

| Klimberg et al.77 | 1998 | IC | 428 | 96.4% | 100% | 0% | 1b |

| Cendan et al.75 | 2005 | FSA | 97 | 58% | 100% | 19% | 1b |

| Tan et al.69 | 2006 | EIO | 25 | 96.7% | – | 20% | 2b |

| Olson et al.73 | 2007 | FSA | 290 | 73% | 99.6% | 5.5% | 1b |

| Valdes et al.80 | 2007 | IC | 61 | 65.7% | 95.5% | 23% | 2b |

IOUS: intraoperative ultrasound; FSA: frozen-section analysis; IC imprint cytology.

Classification of the level of evidence according to The Oxford 2011 levels of evidence, Levels of Evidence Working Group, Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (OCEBM).

Another issue discussed in the assessment of resection margins is whether these margins should be evaluated in the specimen or in the surgical cavity. Routine biopsy of the cavity margin is tempting from the oncological point of view82; however, this attitude does not fit well with the aim of conservative surgery. The inverse relationship between the volume of resected breast tissue and PM has been sufficiently proven.83,84 This relationship is robust enough that infiltration of the cavity margins appears to correlate better with survival than specimen infiltration.85 Thus, some authors conclude that the result of the resection margins of the specimen can be ignored if a study of the cavity margins has been performed.86 However, given the various possible combinations between PM of specimen and cavity87 and the poor correlation established between the two parameters,85 caution is advised when basing the therapeutic approach on cavity margins until new long-term follow-up studies are available.87

ConclusionsThe currently available data do not provide an easy method to resolve the problem of positive tumour margins and their implications. However, the evidence found in the literature allows us to reach the following conclusions:

- (1)

Large lobular multifocal tumours with microcalcifications, the presence of DCIS, and patient age <45 years represent independent risk factors for positive margins and should be taken into account when planning the surgical strategy.

- (2)

Data published so far regarding predictors of residual disease in a female patient with positive margins imply that reoperation cannot be avoided in this situation.

- (3)

The ROLL and IOUS techniques appear to be superior to the harpoon procedure with regard to comfort for the patient and the rates of positive margins and reoperations, so they are emerging as the localisation methods of choice in the short term.

- (4)

Intraoperative assessments of margins by ultrasound or mammography and by histological techniques such as FSA and IC have sufficiently demonstrated their utility by decreasing the rate of positive margins and reoperations. Thus, introducing them into conservative surgery protocols would improve the results of the procedures.

Once all these elements are known, individualisation, common sense and prudence should prevail in decision-making and during surgery to avoid most reoperations after conservative breast cancer surgery, though it must be borne in mind that, once margins are free, larger resection margins do not mean a lower probability of local recurrence. New technological developments in this field predict a promising future that is yet to be discovered.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Medina Fernández FJ, Ayllón Terán MD, Lombardo Galera MS, Rioja Torres P, Bascuñana Estudillo G, Rufián Peña S. Los márgenes de resección en la cirugía conservadora del cáncer de mama. Cir Esp. 2013;91:404–412.