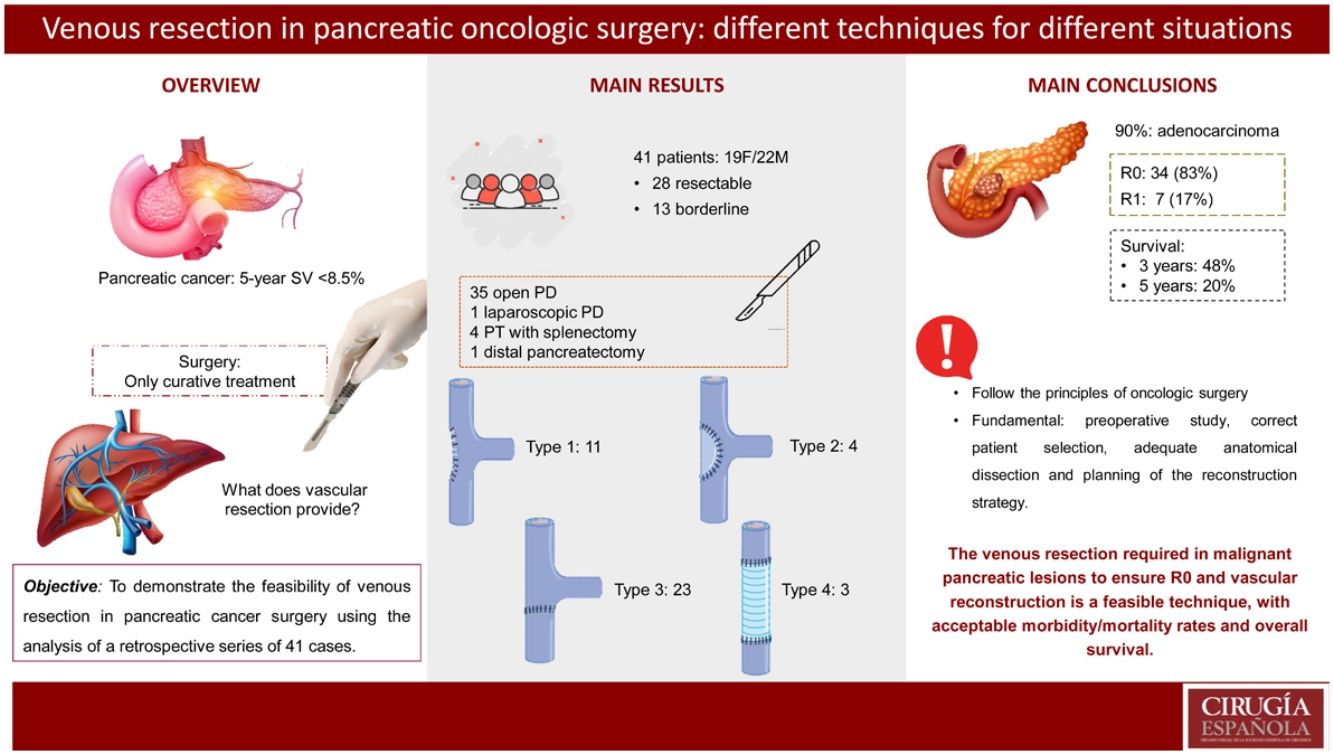

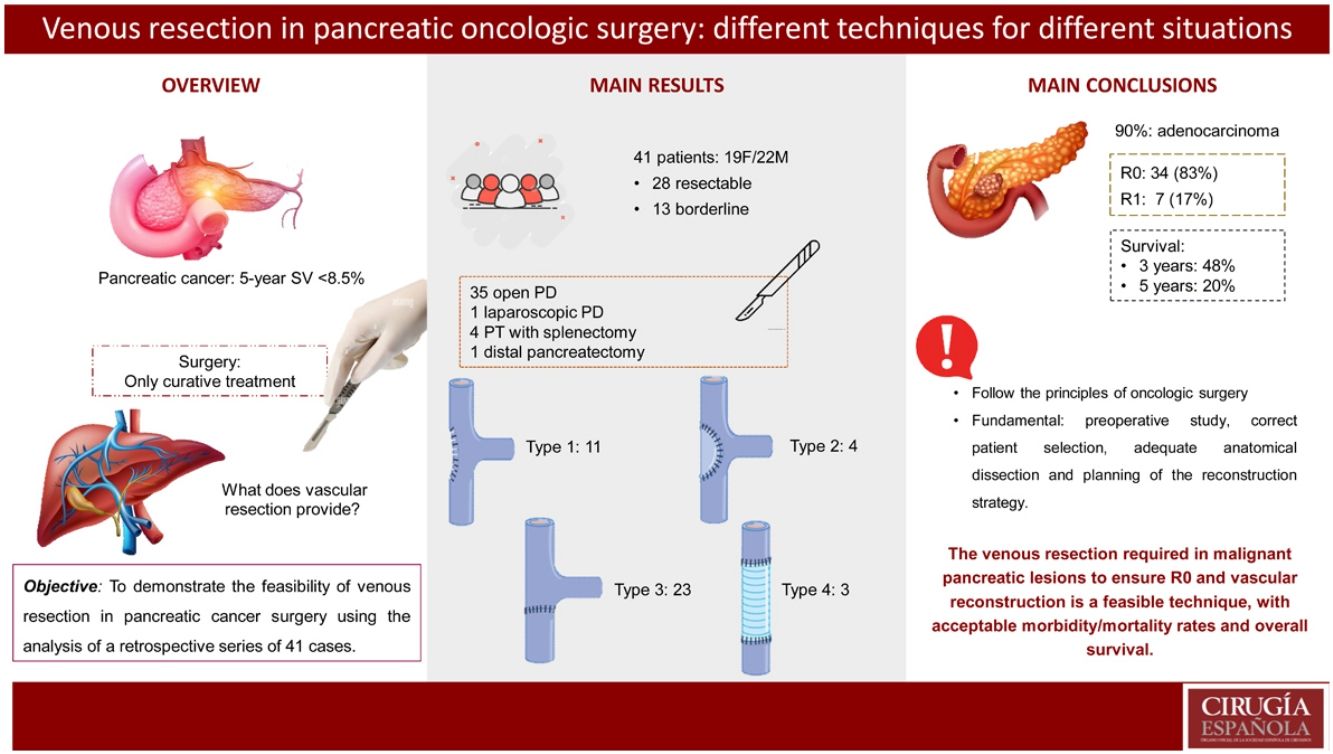

To report the clinical results of patients with malignant pancreatic lesions who underwent oncological surgery with vascular resection. The type of intervention performed, types of vascular reconstruction, the pathological anatomy results, postoperative morbidity and mortality, and survival at 3 and 5 years were analyzed.

MethodsRetrospective, cross-sectional and comparative analysis. We include 41 patients with malignant pancreatic lesions who underwent surgery with vascular resection due to vascular involvement, from 2013 to 2021.

ResultsThe most performed surgery was pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure) using median laparotomy, in 35 out of the 41 patients (85%). One of the cases in the series was performed laparoscopically. Type 1 reconstruction (simple suture) was performed in 11 (27%) patients, type 2 in 4 (10%) cases, type 3 (end-to-end) in 23 (56%) cases, and type 4 reconstruction by autologous graft in 3 (7%) cases. The mean length of the resected venous segment was 21 (11−46) mm, and mean surgical time was 290 (220−360) minutes. 90% (37/41) were pancreatic adenocarcinoma. 83% were considered R0, and there was involvement in the resected vascular section in 41% of the cases. Four patients had Clavien Dindo morbidity >3, and there were no cases of postoperative mortality. Survival at 3 years was 48% and at 5 years 20%.

ConclusionsThe aggressive surgical treatment with venous resection in pancreatic malignant lesions to ensure R0 and its vascular reconstruction is a feasible technique, with an acceptable morbid-mortality rate and overall survival.

Análisis de los resultados de resección venosa en cirugía pancreática oncológica de dos centros de referencia. Se analiza el tipo de intervención realizada, tipos de reconstrucción vascular, el estudio anatomopatológico, la morbimortalidad postoperatoria y la supervivencia a 3 y 5 años.

MétodosAnálisis retrospectivo, transversal y comparativo. Se incluyen 41 pacientes intervenidos de lesiones neoplásicas pancreáticas desde 2003 hasta 2021 que requirieron resección venosa por afectación vascular.

ResultadosLa técnica quirúrgica más frecuente fue la duodenopancreatectomia cefálica tipo Whipple, realizada en 35 de los 41 pacientes (85%). Uno de los casos se realizó por acceso laparoscópico. La reconstrucción vascular tipo 1 (sutura simple) se realizó en 11 pacientes (27%), tipo 2 (patch de falciforme) en 4 casos (10%), tipo 3 (sutura término-terminal) en 23 casos (56%) y la reconstrucción tipo 4 (injerto autólogo) en 3 casos (7%). La longitud media del segmento venoso resecado fue de 21 mm (11–46) y el tiempo quirúrgico medio fue de 290 minutos (220−360). El 90 % (37/41) fueron adenocarcinoma de páncreas. El 83 % se consideraron R0 y hubo afectación en el tramo vascular resecado en el 41% de los casos. Hubo morbilidad Clavien Dindo > 3 en 4 pacientes y no hubo ningún caso de mortalidad postoperatoria. La supervivencia a 3 años fue del 48% y a 5 años del 20%.

ConclusiónesLa resección venosa con reconstrucción para asegurar una resección R0 es una técnica factible, con una aceptable tasa de morbimortalidad y supervivencia global.

Compared to other cancers, pancreatic cancer has one of the worst prognoses, with a 5-year survival rate of less than 8.5%1. Today, surgery continues to be the only curative treatment, but the behavior of the disease means that only 20% of patients are resectable at the time of diagnosis2.

Classically, tumors that were in contact with the superior mesenteric vein (SMV) or the portal vein (PV) were considered a contraindication for surgery.

In 1951, Moore et al. described the first surgery with resection of the PV and SMV for the treatment of locally advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma3. Since then, different vascular reconstruction techniques have been developed, such as PTFE prostheses, autologous vascular grafts, and patches created from the falciform ligament or posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle4.

We present our analysis of the results from a retrospective series of 41 cases operated on with vascular resection, as well as the description of different vascular reconstruction techniques.

MethodsDesignWe have used a prospective database to retrospectively analyze patients who underwent pancreatic cancer surgery with vascular resection from September 2003 to January 2021 at 2 hospitals (Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol from 2017 to 2021, and Hospital Universitario Mútua Terrassa from 2003 to 2021). The registry collected variables for demographic data, tumor type, chemotherapy, surgical treatment, pathological data, and survival.

The inclusion criteria were men and women over the age of 18 who had been diagnosed with resectable or borderline pancreatic neoplasm, who had been assessed by a Multidisciplinary Team who had given their Informed Consent for surgery. The radiological diagnosis and determination of vascular involvement was made by CT scan in compliance with the 2021 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines5. Neoadjuvant treatment was indicated according to the hospital protocol in all borderline resectable patients, and we planned possible vascular resection and reconstruction with preoperative CT scan.

Surgical technique- a)

Resection and assessment of vascular invasion

Bilateral subcostal laparotomy was performed, and the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) was exposed with an extensive Kocher maneuver up to the left renal vein or through the mesocolon at the angle of Treitz. After ensuring that the SMA was not affected, the following was performed: gastric division at the antrum with 2 endostaplers; dissection of the hepatic hilum and division of the bile duct above the cystic duct; clamping and division of the gastroduodenal artery (GDA) at its origin; retropancreatic passage over the SMV/PV and division of the pancreas; division of the first jejunal loop and duodenal uncrossing; dissection of the mesopancreas separating the SMV and the PV, at which time the venous involvement and possible resection were assessed.

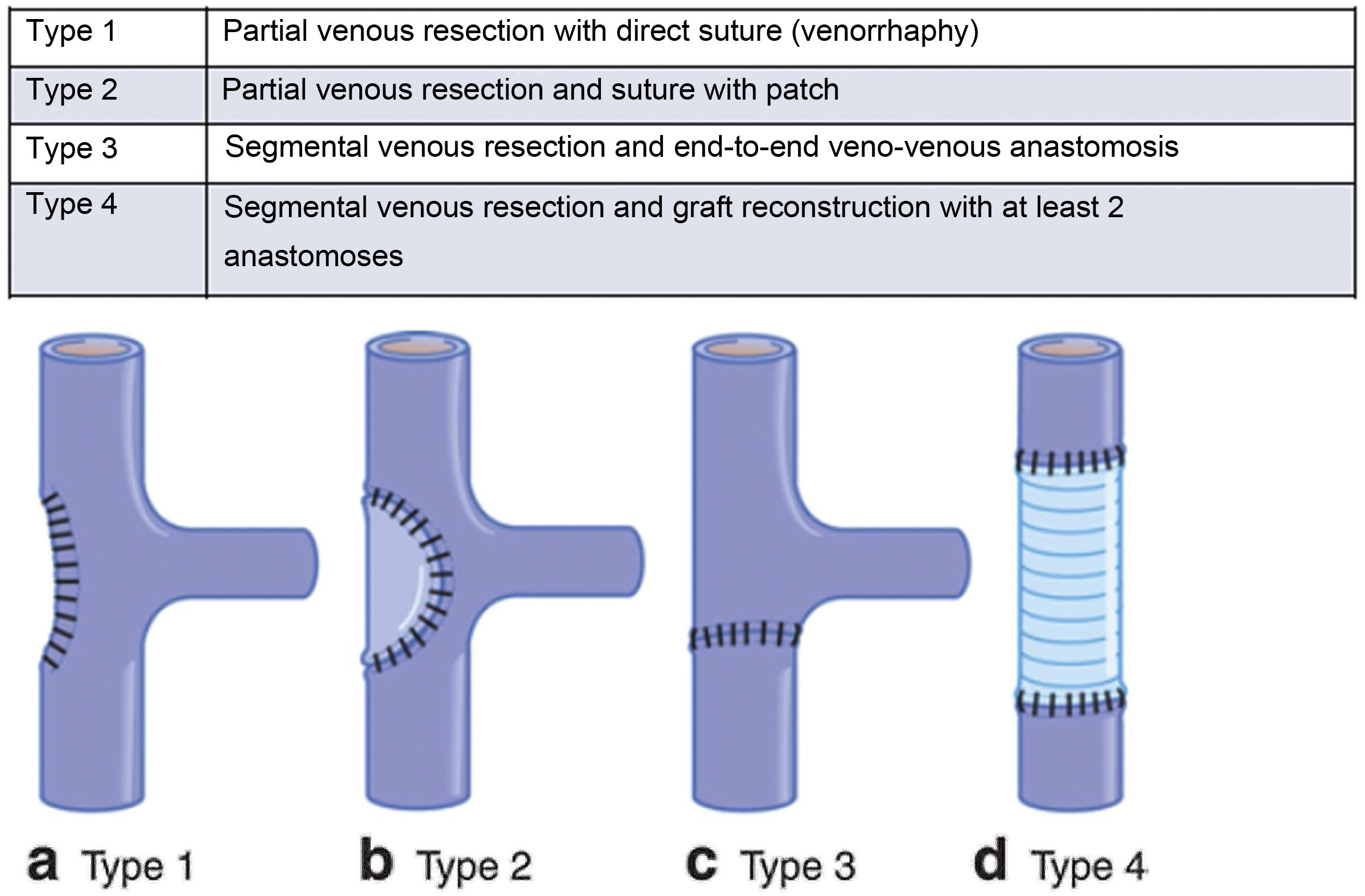

Vascular reconstruction was performed following the International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) classification for venous resection and reconstruction5 (Fig. 1).

International Study Group on Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) classification for venous resections and reconstruction.

Type 1: partial venous resection with direct suture (venorrhaphy).

Type 2: partial venous resection and suture with patch.

Type 3: segmental venous resection and end-to-end veno-venous anastomosis.

Type 4: segmental venous resection and graft reconstruction with at least 2 anastomoses.

The goal of vascular reconstruction is to ensure tension-free repair. To achieve this, the temporary release of the hepatic retractors may be useful, as well as complete hepatic mobilization or an incision at the root of the mesentery to facilitate its ascent. These maneuvers can enable reconstruction by end-to-end anastomosis, even in resections of up to 5 cm6.

However, the technique chosen for reconstruction must be individualized in each case, assessing the location of the tumor, the venous involvement and the length of the vein, as well as the caliber of the reconstruction to avoid stenotic areas and a possible decrease in portal flow. The different types of venous reconstruction are described below:

- •

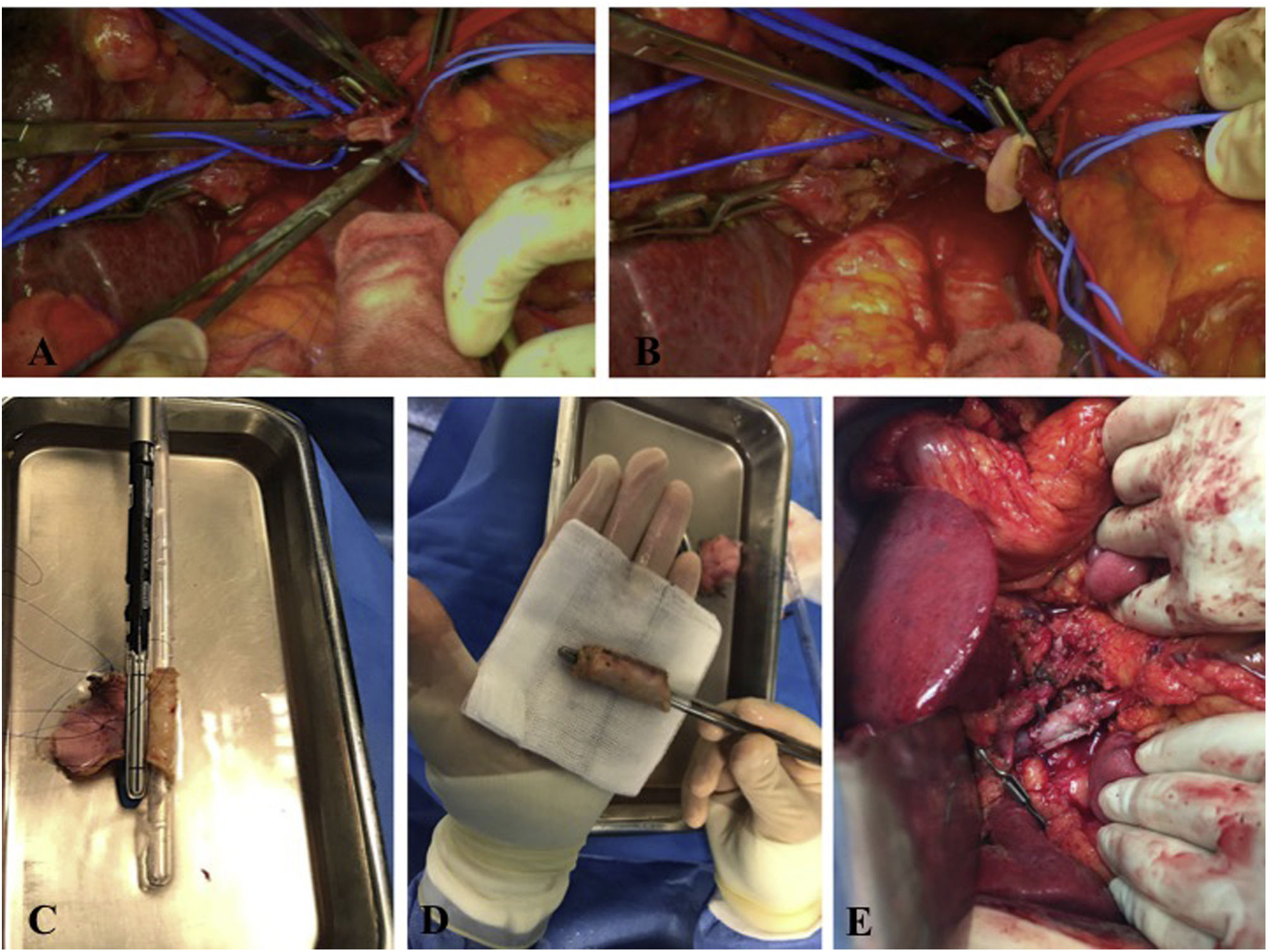

Type 1: Partial vascular resection by lateral clamping of the PV or SMV. For its reconstruction, 4/0 or 5/0 prolene is used for primary suturing (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.A: Intraoperative image: portal vein divided laterally. B: Intraoperative image: reconstruction with falciform patch. C: Reconstruction type 4, using an autologous peritoneal graft and a linear endostapler with a vascular cartridge. D: Final image of the autologous graft created from the peritoneum and posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle. E: Final image of type 4 vascular reconstruction with autologous graft using 2 semicircular running sutures of prolene 4/0 and growth factor to the vessel wall.

(0.37MB). - •

Type 2: Partial resection and patch reconstruction to avoid a tight, kinked, or twisted anastomosis. Patch reconstruction is performed with an autologous lateral falciform ligament graft using a 5/0 prolene running suture (Fig. 2B).

- •

Type 3: Complete/segmental vascular resection and end-to-end veno-venous reconstruction. The anastomosis is performed using a 5/0 prolene running suture on the posterior and anterior sides, taking into account the growth. The vascular clamps are removed, and hemostasis is confirmed. Intraoperative ultrasound helps assess the correct patency of the anastomosis.

- •

Type 4: Complete/segmental vascular resection and graft reconstruction with at least 2 anastomoses. This type of reconstruction is usually necessary in resections larger than 3 cm7, and multiple options have been described (renal vein, internal jugular vein, peritoneum and posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle, or a synthetic graft). In our series, the posterior sheath of the rectus abdominis muscle was used. The peritoneal side is marked so that it faces the interior of the graft, which is placed in a 2.5% glutaraldehyde solution for 5 min for hardening and then rinsed in saline solution for 2 min. To create the tubular graft, a rectal catheter (CH 32) that is similar in diameter to the vessel to be reconstructed is used, and it is then sutured laterally with a linear endostapler (Fig. 2C and D). Finally, the anastomosis is performed with 2 continuous 4/0 prolene sutures (Fig. 2E).

The following technical factors should be considered:

- A)

Comprehensive knowledge of the portal venous system and variants. To facilitate the anatomical recognition of the structures, the hepato-pancreato-venous system can be divided into 5 areas: 1) hepatic hilum; 2) hepatoduodenal ligament; 3) confluence of the splenic and portal veins; 4) infra-pancreatic SMV and its confluence; and 5) splenic vein.

- B)

The use of autologous or synthetic grafts, such as polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE), can be reserved for complete venous resections in which the vascular reconstruction cannot be performed without tension.

- C)

Certain maneuvers, such as releasing retractors and mobilizing the liver from its diaphragmatic attachments, may facilitate a tension-free anastomosis.

- D)

Venous reconstruction must guarantee adequate vein diameter, without torsion.

- E)

The total time of vascular exclusion and reanastomosis should be less than 20 min8.

- A)

The intervention is completed with the creation of the anastomosis according to the Child’s single-loop technique:

- 1 -

Pancreaticojejunal mucosal duct anastomosis with continuous 3/0 barbed suture and mucosal duct tutorized using 5/0 PDS interrupted stitches. If the Wirsung duct is not observed, a pancreatogastric anastomosis is performed with a double crown of 3/0 barbed suture.

- 2 -

Hepaticojejunal anastomosis with 4/0 PDS interrupted stitches or, when the diameter of the bile duct is greater than 1 cm, continuous suture with Stratafix 3/0.

- 3 -

Gastroenteric anastomosis with interrupted 3/0 Vicryl sutures.

All patients were extubated in the operating room and admitted to the Resuscitation Unit. The following day, the nasogastric tube was withdrawn, tolerance to a progressive liquid diet was initiated, and patient mobilization was begun.

When hemodynamically stable, the patient was transferred to the conventional General Surgery ward. Per protocol, 2 abdominal drains were placed during surgery (at the pancreaticojejunal and hepaticojejunal anastomoses), and amylase levels were analyzed on the 1st, 3rd and 5th postoperative days. In the case of outputs <300 cc in 24 h and amylases <150 U/L, the drains are removed from the first postoperative day. All patients received prophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin.

Analysis of variablesThe types of surgical intervention and vascular reconstruction were analyzed. Postoperative morbidity was analyzed according to the Clavien-Dindo classification, while 30-day and 90-day postoperative mortality rates were calculated. The pathological variables included the y/pTNM, resection radicality (R0/R1) and the involvement of the pancreatic, retroperitoneal, vascular and circumferential margins, which were analyzed according to the protocol proposed by Verbeke9.

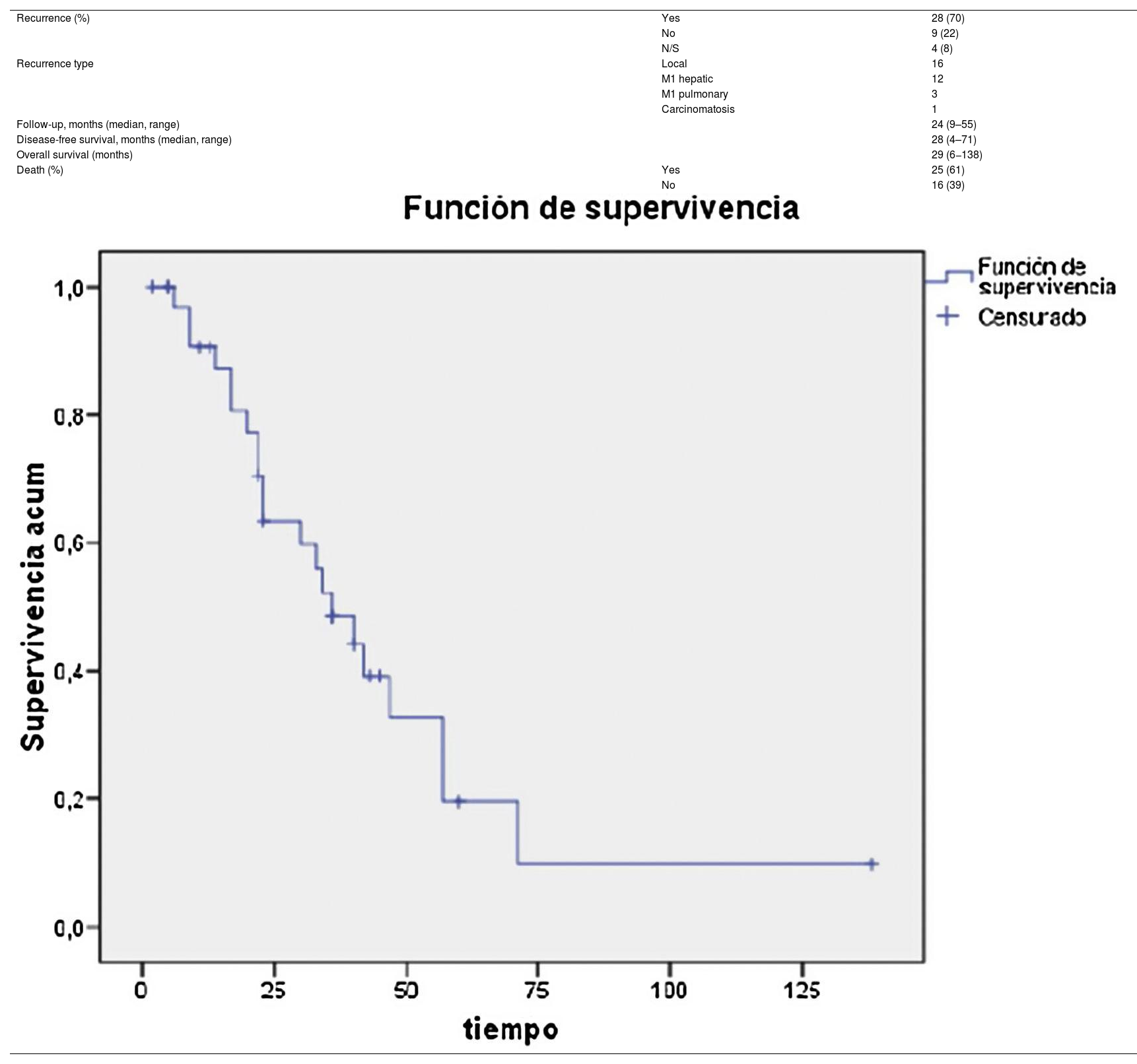

Finally, the type of recurrence, disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival were analyzed.

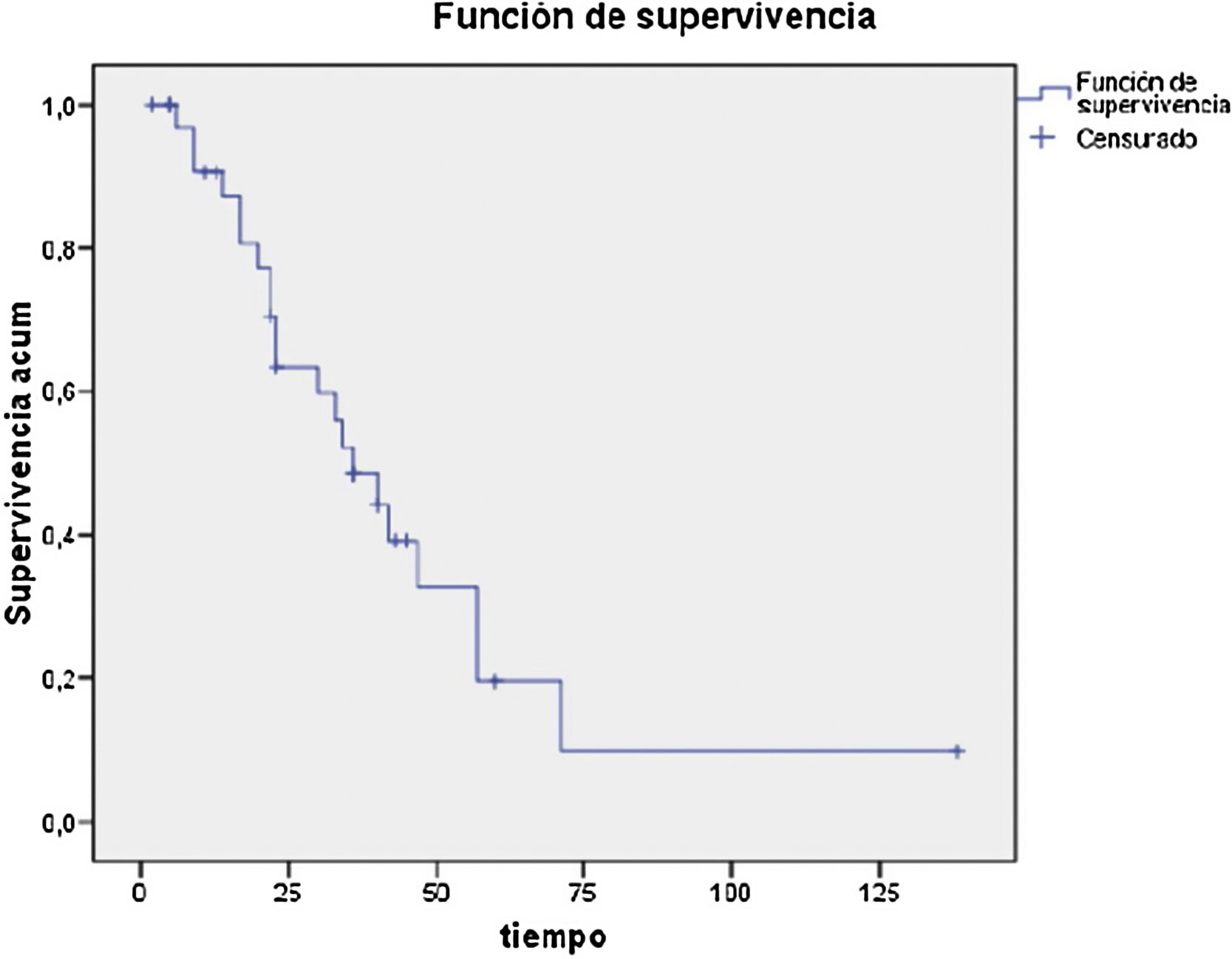

Statistical analysisCategorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and quantitative data as mean and standard deviation (SD). The survival analysis was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method. Analyses were carried out with SPSS version 15.0 for Windows.

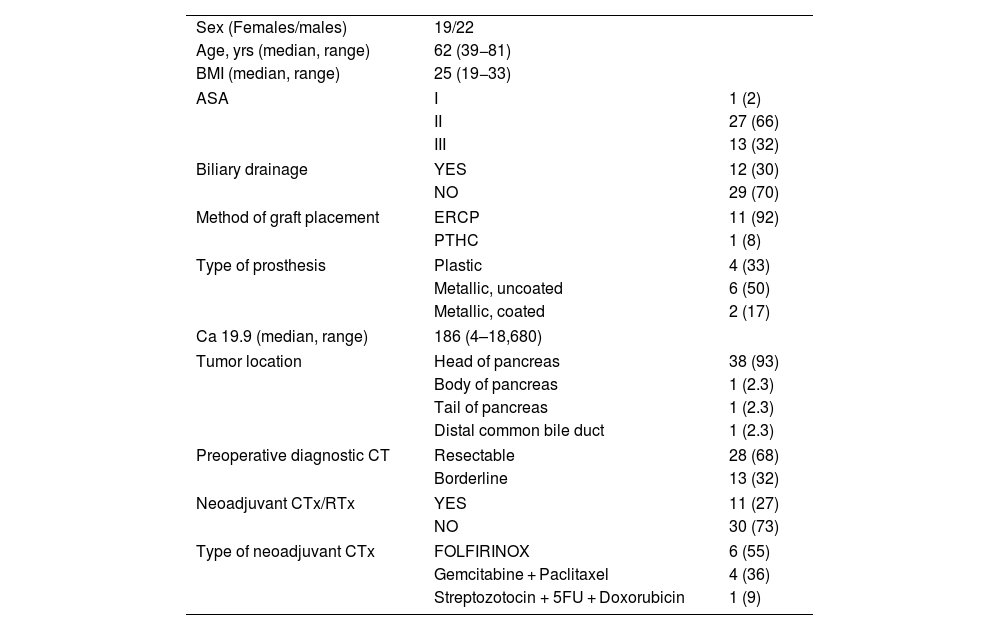

ResultsFrom September 2003 to January 2021, 41 patients (19 females and 22 males) underwent elective surgery at the Hospital Universitario Germans Trias i Pujol (2017–2021) and at the Hospital Universitario Mútua Terrassa (2003–2021). More than half of the patients (58%) were treated between 2017 and 2021.

From September 2003 to January 2021, 520 pancreatic resections were performed, 41 of which required associated resection and vascular reconstruction. In the last 4 years, 24 patients (58% of the total) were treated surgically. Mean patient age was 62 years (39−81), and mean BMI was 25 (19−33). In terms of ASA, 66% of the patients (27/41) were classified as ASA II, one patient was ASA I, and 13 ASA III. Regarding location, 93% of the cases (38/41) were tumors in the head of the pancreas, while the 3 remaining cases were: one in the tail of the pancreas, one in the body of the pancreas, and one cholangiocarcinoma located in the distal common bile duct.

Twenty-eight cases (68%) were considered resectable and 13 (32%) were classified as borderline resectable. Out of these 13 patients, 11 presented positive histology and received neoadjuvant chemotherapy/radiotherapy; the FOLFIRINOX regimen was most frequently used (Table 1). Biliary stents were placed in 12 patients in the series, in 11 by endoscopic retrograde pancreatic cholangiography (ERCP) and in one case by percutaneous transhepatic cholangiography (PTHC).

Clinical characteristics and diagnosis.

| Sex (Females/males) | 19/22 | |

| Age, yrs (median, range) | 62 (39−81) | |

| BMI (median, range) | 25 (19−33) | |

| ASA | I | 1 (2) |

| II | 27 (66) | |

| III | 13 (32) | |

| Biliary drainage | YES | 12 (30) |

| NO | 29 (70) | |

| Method of graft placement | ERCP | 11 (92) |

| PTHC | 1 (8) | |

| Type of prosthesis | Plastic | 4 (33) |

| Metallic, uncoated | 6 (50) | |

| Metallic, coated | 2 (17) | |

| Ca 19.9 (median, range) | 186 (4–18,680) | |

| Tumor location | Head of pancreas | 38 (93) |

| Body of pancreas | 1 (2.3) | |

| Tail of pancreas | 1 (2.3) | |

| Distal common bile duct | 1 (2.3) | |

| Preoperative diagnostic CT | Resectable | 28 (68) |

| Borderline | 13 (32) | |

| Neoadjuvant CTx/RTx | YES | 11 (27) |

| NO | 30 (73) | |

| Type of neoadjuvant CTx | FOLFIRINOX | 6 (55) |

| Gemcitabine + Paclitaxel | 4 (36) | |

| Streptozotocin + 5FU + Doxorubicin | 1 (9) | |

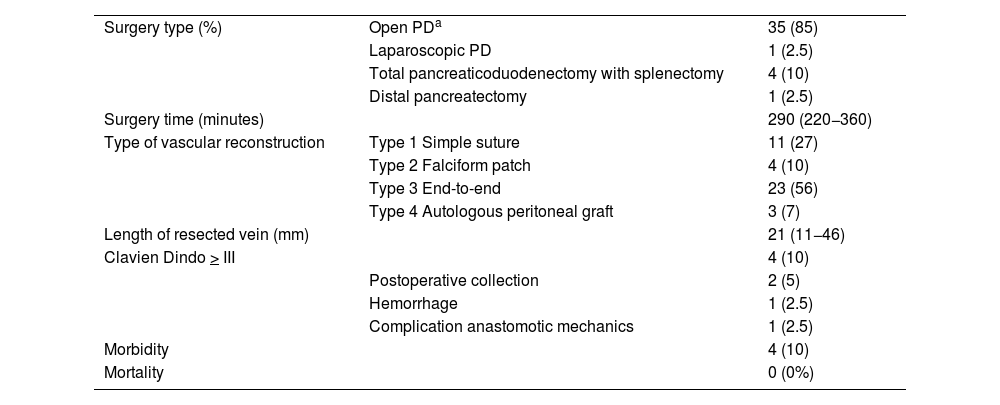

The most commonly performed surgical technique was the Whipple-type pancreaticoduodenectomy, which was used in 35 out of 41 patients (85%).

Type 1 vascular reconstruction was performed in 11 patients (27%), type 2 using a falciform patch in 4 cases (10%), type 3 in 23 cases (56%), and type 4 reconstruction using an autologous graft in 3 cases (7%). The mean length of the resected venous segment was 21 mm (11−46), and the mean surgical time was 290 min (220−360) (Table 2).

Surgical procedure and morbidity.

| Surgery type (%) | Open PDa | 35 (85) |

| Laparoscopic PD | 1 (2.5) | |

| Total pancreaticoduodenectomy with splenectomy | 4 (10) | |

| Distal pancreatectomy | 1 (2.5) | |

| Surgery time (minutes) | 290 (220−360) | |

| Type of vascular reconstruction | Type 1 Simple suture | 11 (27) |

| Type 2 Falciform patch | 4 (10) | |

| Type 3 End-to-end | 23 (56) | |

| Type 4 Autologous peritoneal graft | 3 (7) | |

| Length of resected vein (mm) | 21 (11−46) | |

| Clavien Dindo > III | 4 (10) | |

| Postoperative collection | 2 (5) | |

| Hemorrhage | 1 (2.5) | |

| Complication anastomotic mechanics | 1 (2.5) | |

| Morbidity | 4 (10) | |

| Mortality | 0 (0%) |

Among the 41 patients, 3 presented grade A pancreatic fistula (7%) and 2 grade B (5%). In 4 patients (10%), Clavien Dindo morbidity was >3: 2 patients presented retrogastric collections that required percutaneous drainage; and 2 patients underwent reoperation (one due to bleeding at the vena cava that was resolved with a simple suture; another, after prolonged paralytic ileus, showed signs compatible with torsion of the gastroenteric anastomosis on CT, requiring reoperation with a new anastomosis and Roux-en-Y reconstruction).

There were no cases of postoperative mortality at 30 and 90 days. Follow-up CT scans detected 2 cases (5%) of venous thrombosis due to tumor recurrence and one case (2%) of asymptomatic focal portal stenosis.

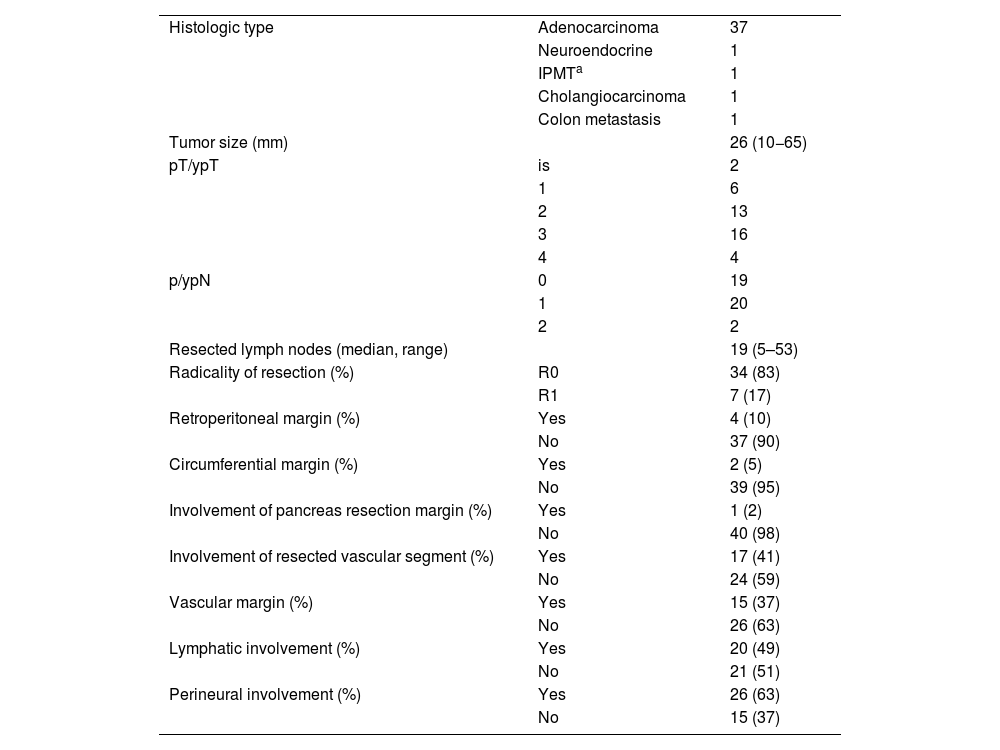

Regarding the histological analysis, 90% (37/41) were identified as pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Mean tumor size was 26 mm (10−65); 83% were considered R0, and the resected vascular section showed involvement in 17 cases (41%) (Table 3). Median survival was 29 months, and disease-free survival 28 months (Table 4).

Histopathological results.

| Histologic type | Adenocarcinoma | 37 |

| Neuroendocrine | 1 | |

| IPMTa | 1 | |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 1 | |

| Colon metastasis | 1 | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 26 (10−65) | |

| pT/ypT | is | 2 |

| 1 | 6 | |

| 2 | 13 | |

| 3 | 16 | |

| 4 | 4 | |

| p/ypN | 0 | 19 |

| 1 | 20 | |

| 2 | 2 | |

| Resected lymph nodes (median, range) | 19 (5–53) | |

| Radicality of resection (%) | R0 | 34 (83) |

| R1 | 7 (17) | |

| Retroperitoneal margin (%) | Yes | 4 (10) |

| No | 37 (90) | |

| Circumferential margin (%) | Yes | 2 (5) |

| No | 39 (95) | |

| Involvement of pancreas resection margin (%) | Yes | 1 (2) |

| No | 40 (98) | |

| Involvement of resected vascular segment (%) | Yes | 17 (41) |

| No | 24 (59) | |

| Vascular margin (%) | Yes | 15 (37) |

| No | 26 (63) | |

| Lymphatic involvement (%) | Yes | 20 (49) |

| No | 21 (51) | |

| Perineural involvement (%) | Yes | 26 (63) |

| No | 15 (37) |

Since Moore et al. reported the first case in 19513, PV/SMV resection has been conducted for the treatment of pancreatic cancer. In the case of borderline pancreatic cancer, the therapeutic approach following NCCN guidelines5 should include neoadjuvant treatment with chemotherapy. The Mellon group10 reported a mean survival rate of 33.5 months in patients who received chemotherapy prior to surgery versus 23.1 months in patients who only received adjuvant therapy.

This clinical strategy combined with the development and improvement of imaging techniques, optimization of the surgical technique, and preoperative prehabilitation have allowed for aggressive surgical techniques and approaches to be performed, thereby offering curative resection to patients who were initially not candidates for surgery.

Thus, several authors have described survival rates after pancreaticoduodenectomy with vascular resection similar to those of conventional PD, with no observed increase in morbidity in experienced hospitals11,12. In our series, we have observed 5-year survival rates of 20%, which was in line with our expectations13,14.

The meta-analysis published by Zhou et al.1 included 2247 patients and concludes that there are no differences in morbidity and mortality or in 5-year survival rates between patients with PV resection versus those who did not undergo venous resection. Tseng et al.15 from the MD Anderson Centre found no difference in survival rates between the 2 groups, and the Yekebas group16 described similar postoperative morbidity and mortality rates between both groups.

In our series, more than half of the patients had undergone surgery in the last 4 years, which shows that a more aggressive surgical approach makes it possible to rescue patients who previously were either not treated surgically or the affected vascular margin was left, thus worsening survival17. Likewise, the consensus document published in 2016 by the ISGPS18 indicates that the scientific evidence to date justifies vein resection in cases of pancreatic cancer, although it recommends that surgery be performed in referral hospitals.

In 2015, Landi et al.19 published a series of 78 patients, 10 of whom required resection of the superior mesenteric vein due to tumor involvement. The complication rate in the vein resection group was significantly lower than a standard PD (63% vs 30%; P = .04), and 9 cases had CD complications >3 in the standard PD group (P = .115). In our series of 41 patients who underwent vascular resection, we observed 4 patients with a Clavien Dindo morbidity >3. In our opinion, however, these patients who underwent aggressive surgical treatment require close monitoring and a proactive approach to anticipate possible complications and carry out treatment early.

The results of our series and previously published data demonstrate that isolated venous involvement is not a contraindication for pancreatic resection as part of a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach for localized pancreatic cancer. Vascular resection and reconstruction can be performed safely and does not affect patient survival.

ConclusionVascular resections with reconstruction must ensure the principles of oncological surgery. A wide variety of surgical approaches and vascular procedures have been described to ensure safe and successful tumor removal. Pancreatic cancer surgery with associated vascular resection due to tumor involvement is a safe and reproducible technique by expert surgeons. However, thorough preoperative study and preparation, correct patient selection, as well as adequate anatomical dissection and planning of the reconstruction strategy, are essential for the success of this surgery.