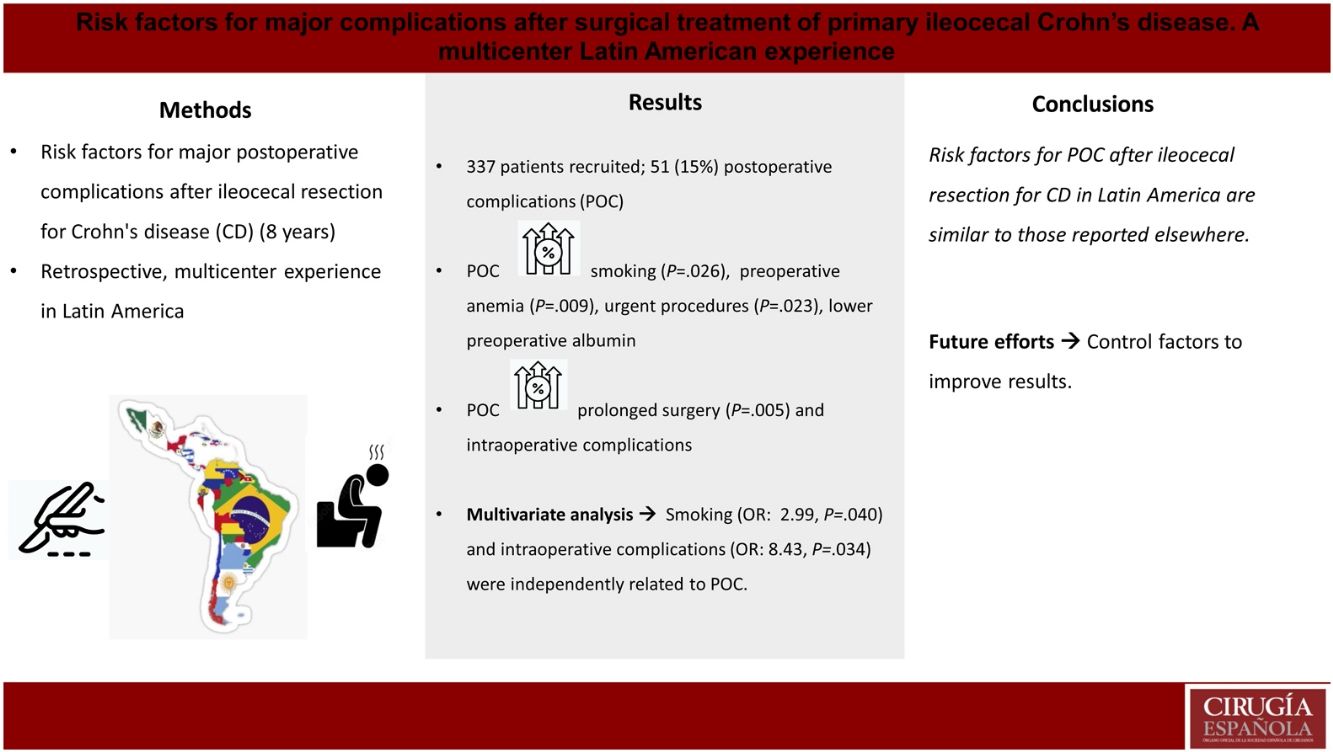

Complications after ileocecal resection for Crohn’s disease (CD) are frequent. The aim of this study was to analyze risk factors for postoperative complications after these procedures.

Materials and methodsWe conducted a retrospective analysis of patients treated surgically for Crohn’s disease limited to the ileocecal region during an 8-year period at 10 medical centers specialized in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Latin America. Patients were allocated into 2 groups: those who presented major postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo > II), the “postoperative complication” (POC) group; and those who did not, the “no postoperative complication” (NPOC) group. Preoperative characteristics and intraoperative variables were analyzed to identify possible factors for POC.

ResultsIn total, 337 patients were included, with 51 (15.13%) in the POC cohort. Smoking was more prevalent among the POC patients (31.37 vs. 17.83; P = .026), who presented more preoperative anemia (33.33 vs. 17.48%; P = .009), required more urgent care (37.25 vs. 22.38; P = .023), and had lower albumin levels. Complicated disease was associated with higher postoperative morbidity. POC patients had a longer operative time (188.77 vs. 143.86 min; P = .005), more intraoperative complications (17.65 vs. 4.55%; P < .001), and lower rates of primary anastomosis. In the multivariate analysis, both smoking and intraoperative complications were independently associated with the occurrence of major postoperative complications.

ConclusionThis study shows that risk factors for complications after primary ileocecal resections for Crohn’s disease in Latin America are similar to those reported elsewhere. Future efforts in the region should be aimed at improving these outcomes by controlling some of the identified factors.

Las complicaciones posteriores a resección ileocecal por enfermedad de Crohn (EC) son frecuentes. El objetivo de este estudio fue analizar los factores de riesgo para presentar complicaciones postoperatorias después de estos procedimientos.

Materiales y métodosSe realizó un análisis retrospectivo de pacientes operados por enfermedad de Crohn limitada a la región ileocecal durante un período de 8 años en diez centros especializados en enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) de América Latina. Los pacientes fueron divididos en dos grupos, los que presentaron complicaciones postoperatorias mayores (Clavien–Dindo > II) (denominado grupo de complicaciones postoperatorias - POC) y los que no (grupo sin complicaciones postoperatorias - NPOC). Se analizaron las características preoperatorias y las variables intraoperatorias para identificar posibles factores relacionados a POC.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 337 pacientes, 51 (15,13%) en el grupo con POC. El grupo POC presentó mayor índice de tabaquismo (31,37 vs. 17,83, p = 0,026), quienes presentaron más anemia preoperatoria (33,33 vs. 17,48%, p = 0,009), urgencias (37,25 vs. 22,38, p = 0,023) y menores niveles de albúmina. Los procedimientos por enfermedad complicada se asociaron con una mayor morbilidad postoperatoria. Los pacientes con POC tuvieron un tiempo operatorio más largo (188,77 vs. 143,86 minutos, p = 0,005), más complicaciones intraoperatorias (17,65 vs. 4,55%, p < 0,001) y menores tasas de anastomosis primaria. En el análisis multivariado, tanto tabaquismo como complicaciones intraoperatorias se asociaron de forma independiente con la aparición de complicaciones mayores postoperatorias.

ConclusiónEste estudio demuestra que los factores de riesgo de complicaciones posteriores a resecciones ileocecales primarias por EC en América Latina son similares a los reportados en otros lugares. Los esfuerzos futuros en la región deben estar dirigidos a mejorar estos resultados mediante el control de algunos de los factores identificados.

Crohn’s disease (CD) is a chronic condition associated with transmural inflammation, which commonly affects the ileocecal region.1 In these patients, repeated flare-ups of the disease are associated with complications (fibrotic stenosis or fistulae). Surgery is still needed in a significant percentage of patients, even despite significant advances in medical therapy.2

As in other parts of the world, the prevalence of Crohn's disease is rising in Latin America, with some of the highest numbers reported in Brazil and Argentina (approximately 24 and 15 patients/100 000 persons).3

Ileocecal resections for complicated disease are associated with higher rates of postoperative complications compared to luminal disease.4,5 Therefore, several studies have aimed to identify risk factors associated with higher postoperative morbidity.6

Data regarding the surgical management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in Latin America is scarce. Information about indications and outcomes of ileocecal resections for CD, use of minimally invasive approaches, types of anastomosis, etc., are lacking.7

The aim of this study was to identify possible risk factors associated with postoperative complications in a large cohort of patients who had undergone primary ileocecal resections due to CD in different countries in Latin America.

Materials and methodsEthical considerationsThis study was approved by institutional review boards from all included centers and was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice standards.

Study design and settingThis is a retrospective multicenter study that included consecutive surgical patients treated primarily for CD limited to the ileocecal region, from 10 specialized IBD teaching hospitals in 4 Latin American countries (Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Colombia) over an 8-year period (2012–2020).

An initial analysis of this cohort was performed comparing outcomes of patients operated on for either luminal involvement alone or for disease complications.8

ParticipantsInclusion criteria: Patients who had undergone primary ileocecal resections due to CD, either conventional or laparoscopic, with luminal, stenotic, or penetrating phenotypes.

Exclusion criteria: Previous abdominal procedures associated with CD, missing data on the electronic health records, and age younger than 18 years.

Patient stratificationPatients were allocated into 2 groups according to the presence of major postoperative complications (Clavien–Dindo > II)9 within 30 days of the procedure (POC: postoperative complications, NPOC: no postoperative complications).

Data collection and managementInformation regarding patients’ comorbidities and operative procedures were collected in an electronic database, which was validated by 3 experts in colorectal surgery and biostatistics to identify key issues and to maximize completeness and accuracy of data. Local investigators compiled their specific databases, which were combined by the primary author (NA). The lead investigators (NA and PGK) checked the accuracy of all cases to ensure data quality. When missing data were identified, the local lead investigator was contacted and asked to complete the records.

Variables analyzedPreoperative variables included patient demographics (comorbidities stratified by Charlson’s Comorbidity Index), smoking status, preoperative anemia and albumin levels, ASA score and history of previous abdominal procedures.

Variables associated with Crohn’s disease included time from CD diagnosis to surgery (disease duration), Montreal classification, exposure to biological agents before surgery and within 12 weeks of the operative procedure, history of perianal disease, previous exposure to corticosteroids at the time of surgery (defined as receiving more than 20 mg/day of Prednisolone for more than 6 weeks),10 and requirement of preoperative nutrition optimization before the procedure (defined as patients who needed to be hospitalized in order to receive enteral or parenteral nutrition before surgery). Percentage of early surgery (for luminal involvement, as defined by Maruyama et al.)11 or surgery for disease complications (stenoses or fistulae) were also evaluated.

Intraoperative factors included operative time, character of surgery (urgent or elective), operative approach and conversion rate, presence of intraoperative complications and their respective stratification following the CLASSIC Classification,12 requirements of associated procedures and rates of primary anastomosis. Decisions regarding the specific type of anastomosis and management of the colonic stump in patients who did not receive an anastomosis were also considered between the 2 groups.

Postoperative factors included length of hospitalization, readmission, reoperation rates, and mortality within 30 days of the procedure.

OutcomesThe main outcome of the study was to compare preoperative and intraoperative characteristics between the POC and NPOC groups, aiming to identify possible risk factors associated with 30-day postoperative major complications.

Statistical analysisStatistical analysis was performed using Stata Software (v11.1, Statacorp, College Station, Texas, USA). The categorical variables were described as percentages whereas numerical variables were described as mean or median (accordingly) with their range. The normality of each numerical variable was evaluated visually and with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

We used the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate, for the comparison of categorical variables, and the Student's T or Fisher’s exact test for continuous variables. OR with respective 95% CI were also calculated.

A multivariable analysis using a logistic regression model was performed including all the variables compared with a P value <.05 and those variables considered clinically significant by the investigators. A P value <.05 was considered statistically significant. Our primary outcome variable was the presence of major postoperative complications.

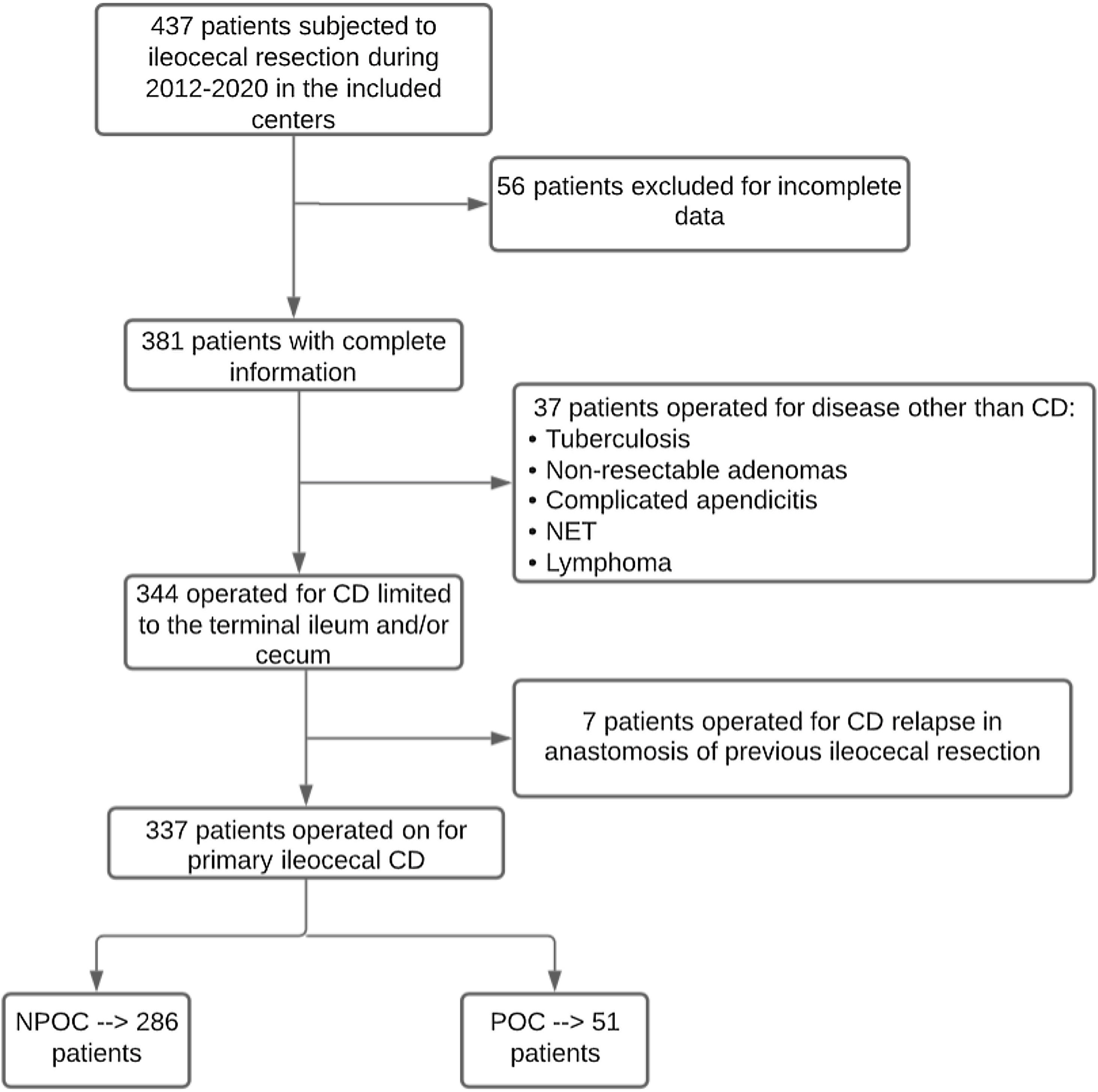

ResultsIn total, 337 patients met the inclusion criteria, 51 of which (15.13%) presented major complications and comprised the POC group. Fig. 1 describes the patient selection process, and Appendix 1 describes the number of patients included per study center.

Preoperative variablesInformation of included patients prior to surgery are described in detail in Table 1. No differences between POC and NPOC groups were identified regarding sex, Charlson comorbidity score, other comorbidities, ASA score, previous abdominal procedures, and time from CD diagnosis to surgery.

Preoperative variables.

| Variables | All patients N = 337 (100%) | NPOC N = 286 (84.87%) | POC N = 51 (15.13%) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female) | 177 (52.52) | 154 (53.85) | 23 (45.10) | 0.249 | 0.70 (0.39–1.28) |

| Age (median, range) | 39.78 (18–89) | 39.16 (18−89) | 43.22 (18–77) | 0.095 | |

| Smoking | 67 (19.88) | 51 (17.83) | 16 (31.37) | 0.026 | 2.11 (1.08–4.12) |

| BMI (median, 95% CI) | 22.87 (13.96 0 37) | 23.09 (14.84–37) | 21.70 (13.96–30.10) | 0.189 | |

| Hypertension | 25 (7.42) | 18 (6.29) | 7 (13.73) | 0.806 | 2.37 (0.93–6.04) |

| Dyslipidemia | 11 (3.26) | 8 (2.80) | 3 (5.88) | 0.253 | 2.17 (0.55–8.52) |

| Charlson comorbidity score (median, range) | 0.60 (0–8) | 0.59 (0–8) | 0.63 (0–6) | 0.843 | |

| Anemia | 67 (19.88) | 50 (17.48) | 17 (33.33) | 0.009 | 2.36 (1.21–4.59) |

| Other comorbidities | 30 (8.90) | 23 (8.04) | 7 (13.73) | 0.189 | 1.81 (0.73–4.51) |

| Previous abdominal surgery | 81 (24.04) | 70 (24.48) | 11 (21.57) | 0.654 | 0.85 (0.41–1.74) |

| Time from diagnosis to surgery (months, median, range) | 63.36 (0–504) | 62.14 (0–300) | 70.18 (0–504) | 0.475 | |

| Character of surgery (Urgent) | 83 (24.63) | 64 (22.38) | 19 (37.25) | 0.023 | 2.06 (1.09–3.90) |

| Luminal vs. complicated disease (Complicated) | 277(82.20) | 230 (80.42) | 47 (92.16) | 0.044 | 2.86 (0.98–8.34) |

| Montreal classification | |||||

| A1 | 21 (6.23) | 20 (6.99) | 1 (1.96) | 0.171 | 0.27 (0.03–2.04) |

| A2 | 235 (69.73) | 197 (68.88) | 38 (74.51) | 0.420 | 1.32 (0.67–2.60) |

| A3 | 81 (24.04) | 69 (24.13) | 12 (23.53) | 0.927 | 0.97 (0.48–1.95) |

| B1 | 60 (17.80) | 56 (19.58) | 4 (7.84) | 0.044 | 0.35 (0.12–1.02) |

| B2 | 155 (45.99) | 131 (45.80) | 24 (47.06) | 0.868 | 1.05 (0.58–1.91) |

| B3 | 101 (29.97) | 84 (29.37) | 17 (33.33) | 0.569 | 1.20 (0.64–2.27) |

| B2−3 | 21 (6.23) | 15 (5.24) | 6 (11.76) | 0.076 | 2.41 (0.88–6.58) |

| Perianal CD | 93 (27.60) | 81 (28.32) | 12 (23.53) | 0.481 | 0.78 (0.39–1.56) |

| Previous steroids | 128 (37.98) | 105 (36.71) | 23 (45.10) | 0.256 | 1.42 (0.77–2.59) |

| Previous exposure to biological agents | 180 (53.41) | 153 (53.50) | 27 (52.94) | 0.942 | 0.98 (0.54–1.78) |

| Number of previous biologics | |||||

| 1 | 114 (63.33) | 95 (33.22) | 19 (37.25) | 0.574 | 1.19 (0.64–2.22) |

| 2 | 58 (32.22) | 52 (18.18) | 6 (11.76) | 0.263 | 0.60 (0.24–1.49) |

| 3 | 8 (4.44) | 6 (2.10) | 2 (3.92) | 0.431 | 1.90 (0.37–9.75) |

| Exposure to biologics within 12 weeks before surgery | 115 (63.89) | 98 (64.05) | 17 (62.96) | 0.913 | 0.95 (0.41–2.23) |

| Requirement of preoperative nutritional optimization | 50 (14.84) | 40 (13.99) | 10 (19.61) | 0.298 | 1.50 (0.69–3.24) |

| Albumin level (median, range) | 3.48 (1.2–5.2) | 3.54 (1.9–5.2) | 3.23 (1.2–4.5) | 0.04 | |

| ASA score | |||||

| I | 62 (18.40) | 55 (19.23) | 7 (13.73) | 0.350 | 0.67 (0.28–1.57) |

| II | 239 (70.92) | 202 (70.63) | 37 (72.55) | 0.781 | 1.10 (0.56–2.14) |

| III | 34 (10.09) | 27 (9.44) | 7 (13.73) | 0.349 | 1.53 (0.62–3.72) |

| IV | 2 (0.59) | 2 (0.70) | 0 | 0.549 | 0.000 |

Univariate comparative analysis of preoperative characteristics between groups. Categorical variables described as percentages whereas numerical variables were described as mean or median (accordingly) with their range. Normality of each numerical variable was evaluated visually and with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate, for the comparison of categorical variables, and the Student's T or Fisher’s exact test for continuous variables. OR with respective 95% CI also calculated.

We created an additional analysis that stratified time from diagnosis to surgery into 3 categories (less than 2 years, 2–5 years, and more than 5 years), which also showed no differences between groups.

On the other hand, POC patients presented higher rates of smoking (31.37% vs. 17.83%, P = .026, OR: 2.11), preoperative anemia (33.33% vs. 17.48%, P = .009, OR: 2.36), and urgent surgery (37.25% vs. 22.38%, P = .023, OR: 2.06). Operations for complicated disease (when compared to luminal phenotype) were also more frequent in the POC group. Albumin levels were lower in the POC group (3.23 vs. 3.54, P = .04). The rate of exposure to steroids at the time of surgery was numerically higher in the POC group, but this difference was not statistically significant (45.10% vs. 36.71%, P = .256). Previous perianal CD, previous use of biological agents, exposure to these drugs within 3 months of surgery, and requirements of preoperative nutrition optimization were similar in POC and NPOC patients. Lastly, no difference was observed regarding exposure to different types of biologic agents and the presence of complications.

Intraoperative variablesIntraoperative information is described in detail in Table 2.

Intraoperative variables.

| Variables | All patients N = 337 (100%) | NPOC N = 286 (84.87%) | POC N = 51 (15.13%) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Operative time (median, range) | 151.43 (45–420) | 143.86 (45–360) | 188.77 (60–420) | 0.005 | |

| Approach | |||||

| Laparoscopic | 173 (51.34) | 148 (51.75) | 25 (49.02) | 0.719 | 0.90 (0.49–1.63) |

| Conventional | 164 (48.66) | 138 (48.25) | 26 (50.98) | 0.719 | 1.11 (0.61–2.03) |

| Conversion rate | 18/173 (10.40) | 14/148 (9.46) | 4/25 (16) | 0.322 | 1.82 (0.54–6.11) |

| Requirement of associated procedures | 53 (15.73) | 41 (14.34) | 12 (23.53) | 0.097 | 1.84 (0.89–3.82) |

| Intraoperative complications | 22 (6.53) | 13 (4.55) | 9 (17.65) | 0.000 | 4.50 (1.78–11.38) |

| CLASSIC Minor | 19/22 (86.36) | 13/22 (100) | 6/9 (66.67) | 0.025 | |

| CLASSIC Major | 3/22 (13.64) | 0 | 3/9 (33.33) | 0.025 | |

| Primary anastomosis | 310 (91.99) | 268 (93.71) | 42 (82.35) | 0.006 | 0.31 (0.13 – 0.75) |

| Type of anastomosis | |||||

| Hand-sewn | 47/310 (15.16) | 38/268 (14.18) | 9/42 (21.43) | 0.223 | 1.81 (0.82–4.03) |

| Stapled | 263/310 (84.84) | 230/268 (85.82) | 33/42 (78.57) | 0.223 | 0.61 (0.27–1.37) |

| Hand-sewn | |||||

| One layer | 23/47 (48.94) | 18/38 (47.37) | 5/9 (55.56) | 0.882 | 1.11 (0.27–4.54) |

| Two-layer | 24/47 (51.06) | 20/38 (52.63) | 4/9 (44.44) | 0.477 | 0.60 (0.24–2.53) |

| Anastomotic configuration | |||||

| End- to-end | 28/310 (9.03) | 25/268 (9.33) | 3/42 (7.14) | 0.646 | 0.96 (0.31–3.00) |

| End-to-side | 30/310 (9.68) | 27/268 (10.07) | 3/42 (7.14) | 0.550 | 0.96 (0.31–3.00) |

| Side-to-side | 252/310 (81.29) | 216/268 (80.60) | 36/42 (85.71) | 0.429 | 1.44 (0.58–3.62) |

| Anastomotic orientation | |||||

| Isoperistaltic | 57/310 (18.39) | 51/268 (19.03) | 6/42 (14.29) | 0.461 | 1.41 (0.56–3.53) |

| Anti-peristaltic | 253/310 (81.61) | 217/268 (80.97) | 36/42 (85.71) | 0.461 | 0.82 (0.34–1.96) |

| Decision after resection | |||||

| Anastomosis w/o diversion | 292 (86.65) | 252 (88.11) | 40 (78.43) | 0.061 | 0.49 (0.23–1.05) |

| Diverted anastomosis | 18 (5.34) | 15 (5.24) | 3 (5.88) | 0.852 | 1.13 (0.31–4.06) |

| End ileostomy, intra abdominal stump | 7 (2.08) | 5 (1.75) | 2 (3.92) | 0.316 | 2.29 (0.43–12/22) |

| End ileostomy, subcutaneous stump | 13 (3.86) | 11 (3.85) | 2 (3.92) | 0.979 | 1.02 (0.22–4.76) |

| End ileostomy, mucous fistula | 7 (2.08) | 3 (1.05) | 4 (7.84) | 0.002 | 8.03 (1.70–37.96) |

| Postoperative antibiotics | 169 (50.15) | 130 (45.45) | 39 (76.47) | 0.000 | 3.90 (1.92–7.90) |

Univariate comparative analysis of intraoperative characteristics between groups. Categorical variables described as percentages whereas numerical variables were described as mean or median (accordingly) with their range. Normality of each numerical variable was evaluated visually and with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate, for the comparison of categorical variables, and the Student's T or Fisher’s exact test for continuous variables. OR with respective 95% CI also calculated.

Patients from the POC group had a significantly longer mean operative time (188.77 vs. 143.86, P = .005), numerically higher rates of associated procedures (23.53% vs. 14.34%, P = .097) and intraoperative complications (17.65% vs. 4.55%, P < .001). In contrast, patients in the NPOC group presented a higher rate of primary anastomosis (93.71% vs. 82.35%, P = .006) and lower need for postoperative antibiotics (45.45% vs. 76.47%, P < .001, OR: 3.90).

The overall rate of minimally invasive surgery was 51.34%, with no difference between groups in terms of initial laparoscopic approach. Even though conversion rates were numerically higher in the POC group, the difference was not significant (16% vs. 9.46%, P = .322). Different types of anastomoses were included in the analysis. Side-to-side, anti-peristaltic stapled anastomosis was the most common anastomotic configuration. No differences were identified between the groups regarding the specific type of anastomosis. Lastly, regarding management of the colonic stump in patients without primary anastomosis, POC patients presented a higher proportion of ileostomy and colonic mucous fistula.

Postoperative outcomesPostoperative variables are listed in Table 3. Patients from the POC group had significantly longer hospitalization stay (19.54 vs. 5.48 days, P < .001), higher rates of readmissions to hospital (35.29% vs. 4.20%, P < .001), reoperations (66.67% vs. 1.75, P < .001) and mortality (7.84 vs. 0, P < 0.001) within 30 days of the index operation.

Postoperative variables.

| Variables | All patients N = 337 (100%) | NPOC N = 286 (84.87%) | POC N = 51 (15.13%) | P value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization length in days (median, 95% CI) | 8.03 (2–81) | 6.01 (2–35) | 19.54 (6–81) | 0.000 | |

| Readmission to hospital | 30 (8.90) | 12 (4.20) | 18 (35.29) | 0.000 | 12.45 (5.13–30.23) |

| Reoperation | 39 (11.57) | 5 (1.75) | 34 (66.67) | 0.000 | 112.40 (23.98–526.85) |

| Mortality | 4 (1.19) | 0 | 4 (7.84) | 0.000 |

Univariate comparative analysis of postoperative characteristics between groups. Categorical variables described as percentages whereas numerical variables were described as mean or median (accordingly) with their range. Normality of each numerical variable was evaluated visually and with the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi square or Fisher exact tests, as appropriate, for the comparison of categorical variables, and the Student's T or Fisher’s exact test for continuous variables. OR with respective 95% CI also calculated.

In total, 16 patients (5.16%) presented anastomotic leakage after surgery, for which most required reoperation.

Multivariate analysisTable 4 describes the results of multivariable analysis. Smoking (OR = 2.99, P = .040) and intraoperative complications (OR=8.43, P = .034) were independently associated with the occurrence of major postoperative complications.

Multivariate analysis.

| Variables | OR | Standard Error | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | 2.99 | 1.605 | 0.040 | 1.05– 8.56 |

| Preoperative Anemia | 1.43 | 0.710 | 0.476 | 0.54–3.79 |

| Urgency setting | 0.69 | 0.377 | 0.497 | 0.236–2.015 |

| Surgery for complications of the disease | 1.69 | 1.455 | 0.544 | 0.31–9.15 |

| Preoperative albumin level | 0.57 | 0.205 | 0.120 | 0.29–1.16 |

| Operative time | 1.00 | 0.002 | 0.236 | 0.99–1.01 |

| Intraoperative complications | 8.43 | 8.472 | 0.034 | 1.18–60.44 |

| Primary anastomosis | 1.08 | 0.626 | 0.895 | 0.35–3.37 |

| Need for postoperative antibiotics | 1.08 | 0.626 | 0.895 | 0.35–3.37 |

Multivariable analysis using a logistic regression model including all the variables compared with a p value of less than 0.05 and those variables considered clinically significant by the investigators. A p value below 0.05 was considered statistically significant, using postoperative major complications as dependent variable.

This study presents a large group of patients operated on for primary ileocecal CD and comprises one of the first international multicenter experiences about surgical treatment of patients with CD from different Latin America countries. In the multivariable analysis, smoking and intraoperative complications were independently associated with higher rates of postoperative morbidity.

Because postoperative morbidity after resection is still a major problem in the management of CD (especially when compared to other intestinal problems),13 several recent studies have aimed to determine specific factors that could potentially affect postoperative outcomes. Certain risk factors for major complications have been extensively described, such as smoking,14 preoperative anemia,15,16 urgent procedures,14,17 penetrating disease,5,15,17–20 hypoalbuminemia,20–22 and previous exposure to steroids.14,18,19,23 Our study presented similar findings in the univariate analysis, where smoking, preoperative anemia, urgent surgery and complicated disease (stenotic or penetrating) were more frequently observed in patients with postoperative complications.

In addition, previous exposure to biological agents has been the object of endless debate regarding its possible association with worse postoperative outcomes. Although some studies have identified a correlation between preoperative anti-TNF agents and higher rate of postoperative complications,16,23–25 a large meta-analysis based on information from 18 non-randomized studies failed to find an association between infliximab and total complications.27 Furthermore, the prospective multicentric PUCCINI trial28 evaluated postoperative morbidity in IBD patients exposed to biologics and likewise could not demonstrate an association between these drugs and worse postoperative outcomes. Overall rates of infections (18.1% vs. 20.2%, P = .469) and surgical site infections (12.0% vs. 12.6%, P = .889) were similar in patients previously exposed to anti-TNF agents and those unexposed. In the multivariable analysis, current exposure to these agents was not associated with overall infections (OR, 1.050; 95% CI, 0.716–1.535) or surgical site infection (OR, 1.249; 95% CI, 0.793–1.960). Detectable concentrations of anti-TNF agents were not associated with infectious complications. In our study, preoperative exposure to biologics was observed in 52.94% of patients with major postoperative complications and 53.5% of those without morbidity (P = .942); these findings are compatible with most retrospective studies and the aforementioned prospective PUCCINI trial. Guidelines still do not present specific formal recommendations regarding preoperative use of biologics,29 and more cause-effect relationship studies are warranted.

Few studies have investigated intraoperative factors in ileocecal resections due to CD and their possible relation with postoperative complications. Our study found that prolonged operative time and intraoperative complications negatively impacted postoperative morbidity, whereas a primary anastomosis seemed to work as a protective factor. A possible reason for this finding is that surgeons, facing patients in worse conditions or requiring more complex procedures, could be less eager to perform a primary anastomosis (selection bias). Postoperative antibiotics were also more needed in patients with complications, which could be partially explained by the fact that this group faced more complex surgery, with longer operative time and more complicated disease.

In our study, the presence of postoperative major complications had a major impact on other postoperative indicators, including prolonged hospitalization as well as higher rates of reoperations, readmissions and mortality. This highlights the interest in defining preoperative risk factors for these events, with special interest in modifiable characteristics, such as smoking or delayed surgical indication.

Since this is one of the first multicenter Latin American studies about the surgical treatment of CD patients, it provides an interesting overview of surgery-related characteristics. Initially, the overall 51% rate of laparoscopic procedures seems low in the era of minimally invasive techniques. However, in other studies, the percentage of laparoscopic cases is below 60%.5,14–26,30 This could be due to the fact that the main indications for surgery in patients with CD are disease-related complications, such as long fibrotic stenosis, internal or external fistulae, and inflammatory masses, which may limit surgical approach options.

Overall, the rate of primary anastomosis was high in our cohort of patients, and the most common type and configuration of the anastomoses created (stapled, side-to-side) are compatible with the recommendations of international guidelines.29 Even though there is no consensus on the management of the colon stump when a primary anastomosis is not performed, the tendency for exteriorization as a double-loop stoma or mucous fistula instead of an intra-abdominal stump (which was observed in patients with complications) can be explained by the fact that patients in poor general condition might be at risk of colon stump leakage and consequent septic complications.

Our study is associated with certain inherent limitations, such as its retrospective nature and the low number of patients with complications. Furthermore, practices may vary among medical centers, and the surgeons’ experience and expertise were not evaluated in detail (some cases may have been performed by junior surgeons, others by senior staff members, and some by residents with assistance). Minimally invasive resections were performed in 60% of cases, which reflects the general reality of our continent in colorectal surgery. We also did not analyze possible differences between hospitals, as some study centers included fewer patients than others, and this was not the main purpose of our analysis. Also, the groups were not considered fully homogeneous, as some variables differed between patients with and without associated morbidity. Another limitation is that no specific sample calculation was possible, and we worked with a convenience sample.

On the other hand, the main strength of our study is that it represents the very first solid international multicenter analysis of postoperative outcomes from Latin America, which may assist in surgical management of CD in our region.

In summary, smoking and the presence of intraoperative complications were identified as predictors of major postoperative complications after ileocecal resections in CD and may have an important impact on different postoperative indicators. This international study focuses efforts on gathering more experience in the surgical management of CD in Latin America. Further prospective research aimed at identifying preoperative risk factors for postoperative complications is warranted in order to properly optimize patients for ileocecal resections in our region.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

FundingThis study has not been funded.

Please cite this article as: Surgical IBD Latam Consortium. Risk factors for major complications after surgical treatment of primary ileocecal Crohn's disease. A multicentric Latin American experience. Cir Esp. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cireng.2023.05.002.