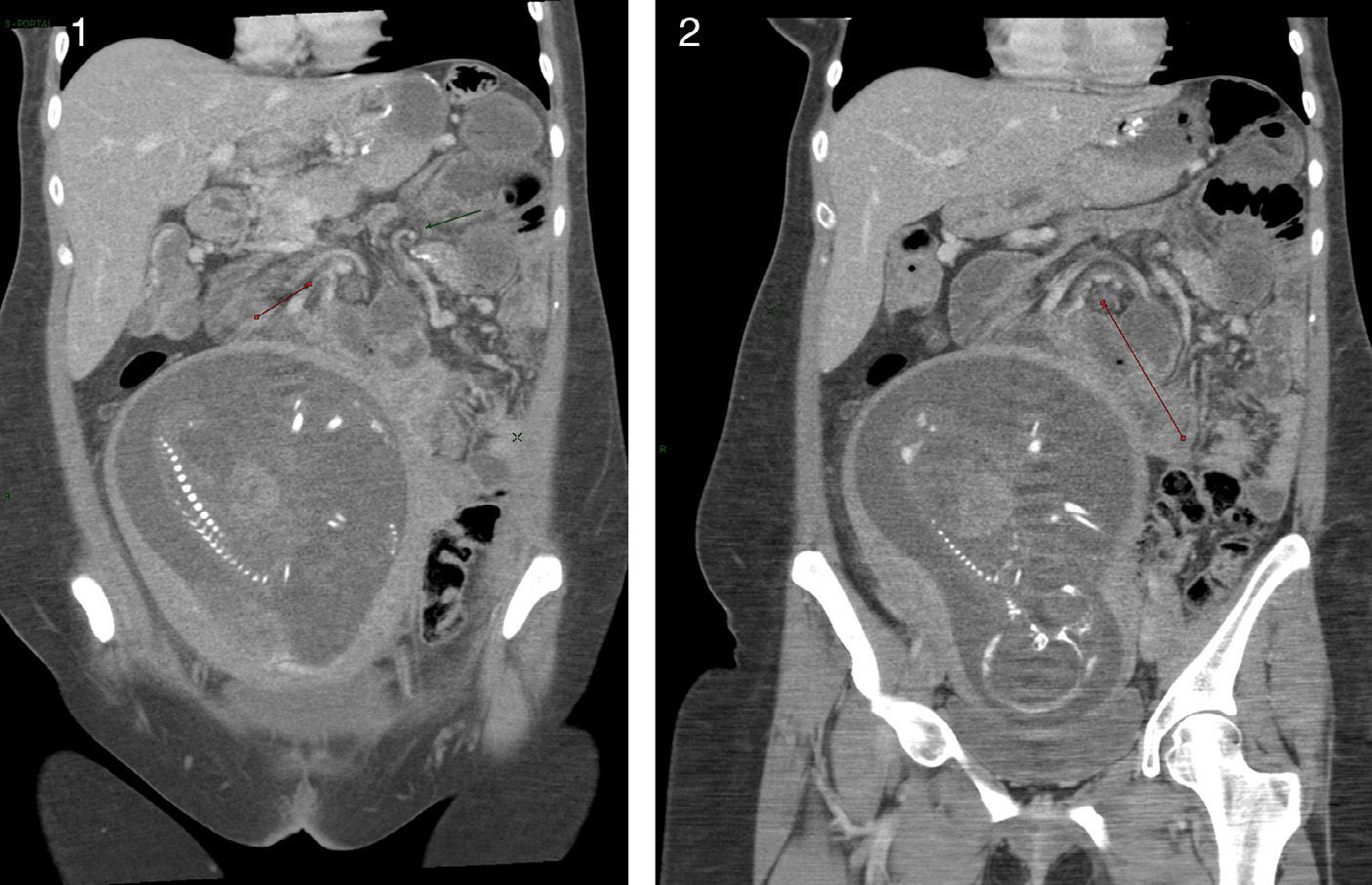

We present the case of a 35-year-old woman who had undergone laparoscopic gastric bypass 15 months earlier, with an expected weight loss of 70%. She came to the Emergency Department during her 6th month of gestation (23 weeks), after a previous hospital discharge just 5 days earlier with a diagnosis of hyperemesis gravidarum, due to persistent vomiting and malaise. Lab work showed no relevant alterations (including PCR and CPK). Abdominal X-ray showed limited air-fluid levels in the small bowel located in the left hypochondrium, and the condition was cataloged as intestinal obstruction due to adhesions. Conservative management was initiated with bowel rest and an NG tube for 48h. At this time, obstetric assessment with ultrasound demonstrated massive CNS fetal hemorrhage, and the family agreed to a voluntary interruption of the pregnancy. Given the worsening clinical and analytical parameters (leukocytosis 13000 and associated hypokalemia) and the evolution of the gestation, an emergency CT was ordered, which showed transmesenteric internal hernia with probable jejunal content, signs of intestinal occlusion, and possible intestinal ischemia (Figs. 1 and 2). Exploratory laparoscopy revealed internal hernia through Petersen's space, with a strangulated intestinal loop and patchy necrosis, which required conversion to open surgery, resection of the loop and creation of a new bypass with 30cm of biliary loop and 50cm of intestinal loop. The postoperative period of the patient was uneventful, and the voluntary interruption of the pregnancy was scheduled for 10 days after the laparotomy. The patient was discharged 15 days after the procedure.

Abdominal CT c/c iv: gestating uterus at 23 weeks; transmesenteric internal hernia with probable jejunal content. Detail of the characteristic whirlpool sign in the mesentery and agglomeration of small bowel loops in the left hypochondrium, with signs of intestinal occlusion and possible intestinal ischemia.

It is well known that internal hernias are one of the most feared late-onset complications of bariatric surgery. Although the laparoscopic approach is currently the gold standard for these procedures, it presents a greater risk for developing hernias due to the limited development of adherences amongst the loops. Their incidence after laparoscopic gastric bypass reached 10% when the procedure first started to be used.1,2 Today, however, this rate has been considerably reduced to 0.2%, thanks to its antecolonic confection and the recommendation of closing all the defects created with unabsorbable sutures.3–7 These hernias usually appear within months of the intervention and their development has been found to be directly related with weight loss and the increased size of the mesenteric defects created during surgery. Women are especially at risk during pregnancy since the progressive increase in intraabdominal pressure caused by gestation can contribute toward the displacement of intestinal loops through the existing mesenteric defects.8

A high level of suspicion is necessary for diagnosis and early resolution, which can be done by simply reducing the herniated content and later closing the gap without the need for intestinal resection. It is for this reason that the presence of abdominal pain or obstructive symptoms in all patients who have undergone bariatric surgery, and especially pregnant women with a history of bariatric surgery, should make us consider the possibility of an internal hernia. Furthermore, the initial symptoms are vague and lab work may either be normal or show non-specific signs, as in our patient. An aggressive approach is necessary in order to avoid disastrous consequences caused by the delay in treatment, which can lead to perforation of the herniated loop in 9.1% of cases and even patient death in 1.6%.4 In the specific situation of pregnant women, the risk for maternal death increases to 9% and fetal death reaches 13.6%.8

Abdominal CT is the best method for diagnosis in order to detect the presence of internal hernia after gastric bypass surgery.9 Nevertheless, in the case of pregnant women, we should take into consideration the moment of fetal development and assess the benefits versus the risk of ionizing radiation on the fetus (which is lower in the third trimester). Under these circumstances, we should not forget that early exploratory laparoscopy plays a fundamental role in both diagnosis and treatment, and it is feasible at any trimester of pregnancy with very limited risk for both the mother and fetus in expert hands. This should always be considered in uncertain cases, especially in the first and second trimesters, periods in which the risk for miscarriage and fetal malformation as a result of radiation is greater.10

Please cite this article as: Socas Macías M, Reguera Rosal J, Alarcón del Agua I, Pérez Vega H, Morales-Conde S. Vómitos, embarazo y bypass gástrico: ¿emergencia bariátrica? Cir Esp. 2014;92:626–627.