Our aim is to analyze the differences between sporadic gastrointestinal stromal tumors and those associated with other tumors.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study including patients with diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumors operated at our center. Patients were divided into two groups, according to whether or not they had associated other tumors, both synchronously and metachronously. Disease free survival and overall survival were calculated for both groups.

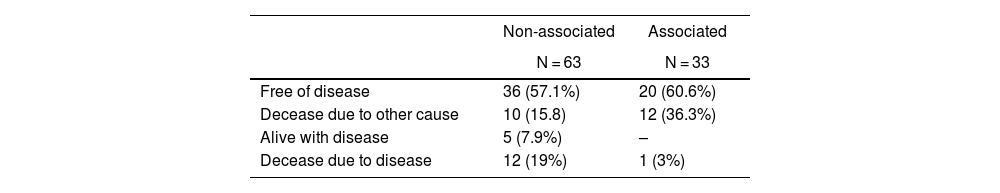

Results96 patients were included, 60 (62.5%) were male, with a median age of 66.8 (35–84). An association with other tumors was found in 33 cases (34.3%); 12 were synchronous (36.3%) and 21 metachronous (63.7%). The presence of mutations in associated tumors was 70% and in non-associated tumors 75%. Associated tumors were classified as low risk tumors based on Fletcher’s stratification scale (p = 0.001) as they usually were smaller in size and had less than ≤5 mitosis per 50 HPF compared to non-associated tumors. When analyzing overall survival, there were statistically significant differences (p = 0,035) between both groups.

ConclusionThe relatively high proportion of gastrointestinal stromal tumors cases with associated tumors suggests the need to carry out a study to rule out presence of a second neoplasm and a long-term follow-up should be carried out in order to diagnose a possible second neoplasm. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors associated with other tumors have usually low risk of recurrence with a good long-term prognosis.

El objetivo de este estudio es analizarsi existen diferencias entre los GIST esporádicos y los que se presentan asociados a otros tumores.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte retrospectivo de pacientes operados de GIST en nuestro centro. Se dividió a los pacientes en función de si presentaban otros tumores asociados o no, de forma sincrónica o metacrónica. La supervivencia libre de enfermedad y la supervivencia global se calcularon en ambos grupos.

ResultadosSe incluyeron un total de 96 pacientes, 60 (62.5%) eran hombres con una media de edad de 66.8 años (35–84). Se encontró una asociación con otros tumores en 33 casos (34.3%); 12 de manera sincrónica (36.3%) y 21 metacrónica (63.7%). La presencia de mutaciones en el grupo de tumores asociados fue del 70% y en el de no asociados del 75%. Los tumores asociados se clasificaron como tumores de bajo riesgo según la escala de Fletcher (p = 0,001), ya que fueron de menor tamaño y presentaron menos de ≤5 mitosis por 50 HPF en comparación con los no asociados. Al analizar la supervivencia global, hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre ambos grupos (p = 0,035).

ConclusiónLa proporción relativamente alta de casos de GIST con tumores asociados sugiere la necesidad de realizar un estudio para descartar la presencia de una segunda neoplasia y, tras el tratamiento de GIST, realizar un seguimiento a largo plazo para diagnosticar una posible segunda neoplasia. Los GIST asociados a otros tumores suelen tener un riesgo bajo de recurrencia con un buen pronóstico a largo plazo.