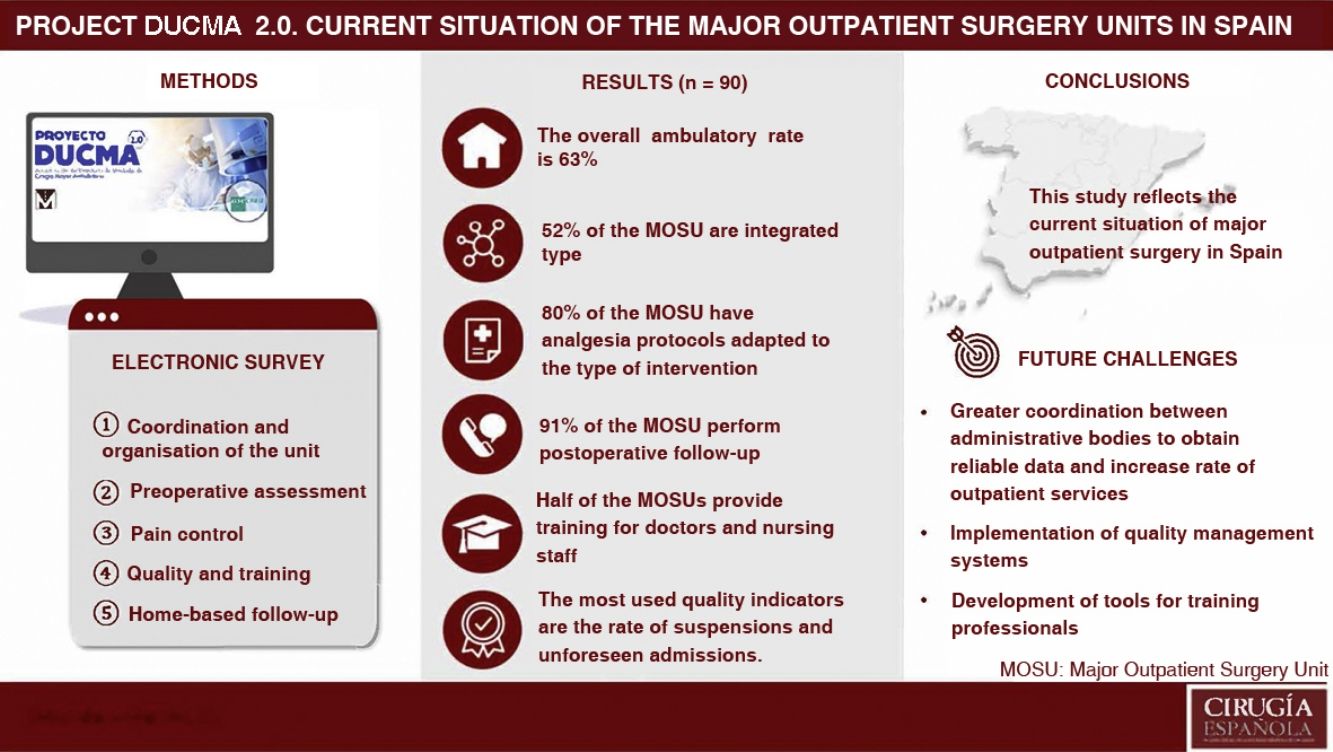

Ambulatory surgery is a safe and efficient management system to solve surgical problems, but its implementation and development has been variable. The aim of this study is to describe the characteristics, structure and functioning of ambulatory surgery units (ASU) in Spain.

MethodsMulticenter, cross-sectional, observational study based on an electronic survey, with data collection between April and September 2022.

ResultsIn total, 90 ASUs completed the survey. The mean overall ambulatory index is 63%. More than half of the ASUs (52%) are integrated units. Around half of the units provide training for physicians (51%) and for nurses (55%). The most frequently used quality indicators are suspension rate (87%) and the rate of unplanned admissions (80%).

ConclusionsGreater coordination between administrations is needed to obtain reliable data. It is also necessary to implement quality management systems in the different units, as well as to develop tools for the adequate training of the professionals involved.

La cirugía mayor ambulatoria (CMA) es un sistema de gestión seguro y eficiente para resolver los problemas quirúrgicos, pero su implantación y desarrollo ha sido variable. El objetivo de este estudio es describir las características, la estructura y el funcionamiento de las unidades de Cirugía Mayor Ambulatoria (UCMA) en España.

MétodosEstudio observacional, transversal, multicéntrico basado en una encuesta electrónica, con recogida de datos entre abril y septiembre de 2022.

ResultadosEn total, 90 UCMA completaron la encuesta. La media del índice de ambulatorización (IA) global es de 63%. Más de la mitad de las UCMA (52%) son de tipo integrado. La mitad las unidades imparte formación para médicos (51%) y personal de enfermería (55%). Los indicadores de calidad más utilizados son la tasa de suspensiones (87%) y de ingresos no previstos (80%).

ConclusionesSe necesita mayor coordinación entre administraciones para obtener datos fiables. Asimismo, se deben implementar sistemas de gestión de calidad en las unidades y desarrollar herramientas para la formación adecuada de los profesionales implicados.

Major outpatient surgery (MOS) is a key element for a viable and sustainable health system,1 since it increases efficiency, with less consumption of resources, without reducing the quality of care.2 With progressive development in Spain3 and, according to data from the Ministry of Health, in 2021 it accounted for 47.6% of the total number of major surgical interventions performed in Spain,4 data far removed from those provided by other neighbouring countries.5 This percentage is called the ambulatory index (AI)6 and measures the proportion of surgical procedures performed in MOS over the total surgical procedures (outpatient and inpatient), thereby showing us the impact of MOS activity on total hospital surgical activity.

To increase the AI, knowledge regarding the characteristics and functioning of the Major Outpatient Surgery Units (MOSU)1,7 is required. There is little real data on the current situation of the MOS in Spain and in the different autonomous communities (AC), despite the figures published by the Ministry.4,8,9

The Spanish Association of Major Outpatient Surgery (ASECMA for its initials in Spanish) launched the DUCMA project (Directory of Major Outpatient Surgery Units) in 2013, a pilot study to understand the reality of the MOSU in Spain. Thirty-eight MOSU participated, a non-representative sample of the MOS in our country. The conclusions of the study indicated that it would be advisable to redefine the survey questions and continue collecting information to expand the sample.3

Given the need for a real update on the current situation of the MOS in our country, ASECMA promoted the initiative of the DUCMA 2.0 project, whose objectives were to describe the structure, characteristics and operation of the MOSU in Spain and, secondary, to identify differences in MOS activity between the different ACs.

MethodsThis is a multicentre cross-sectional observational study based on an electronic survey. All the MOSUs in Spain that formalised their registration in a registry participated. An invitation was sent by email to all hospitals of the National Health System registered in the Ministry of Health and in the ASECMA database. Each MOSU designated a single representative to complete the survey and no exclusion criteria were established.

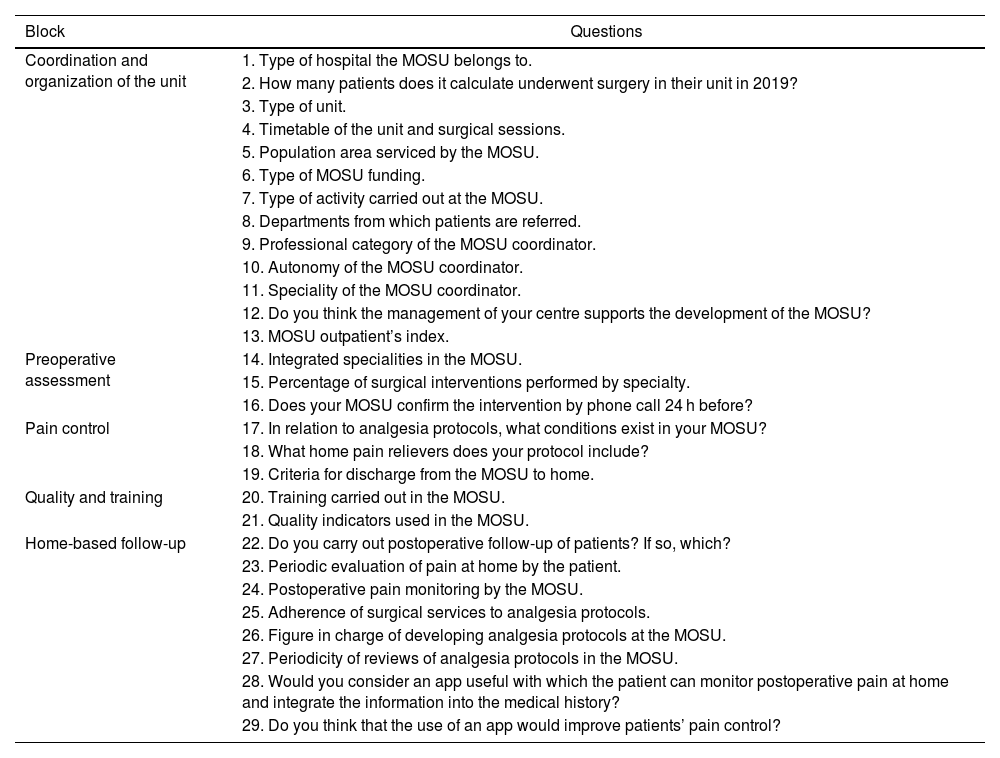

The survey was available to complete from April to September 2022 on the project website.10 The participants’ responses were entered into an electronic data collection notebook. If there were incomplete responses or anomalous values, the MOSU representative was contacted to resolve the discrepancies. The database was closed on October 10, 2022. The survey included 29 questions divided into five blocks, shown in Table 1.

Survey questions to evaluate the current status of the Major Outpatient Surgery Units in Spain.

| Block | Questions |

|---|---|

| Coordination and organization of the unit | 1. Type of hospital the MOSU belongs to. |

| 2. How many patients does it calculate underwent surgery in their unit in 2019? | |

| 3. Type of unit. | |

| 4. Timetable of the unit and surgical sessions. | |

| 5. Population area serviced by the MOSU. | |

| 6. Type of MOSU funding. | |

| 7. Type of activity carried out at the MOSU. | |

| 8. Departments from which patients are referred. | |

| 9. Professional category of the MOSU coordinator. | |

| 10. Autonomy of the MOSU coordinator. | |

| 11. Speciality of the MOSU coordinator. | |

| 12. Do you think the management of your centre supports the development of the MOSU? | |

| 13. MOSU outpatient’s index. | |

| Preoperative assessment | 14. Integrated specialities in the MOSU. |

| 15. Percentage of surgical interventions performed by specialty. | |

| 16. Does your MOSU confirm the intervention by phone call 24 h before? | |

| Pain control | 17. In relation to analgesia protocols, what conditions exist in your MOSU? |

| 18. What home pain relievers does your protocol include? | |

| 19. Criteria for discharge from the MOSU to home. | |

| Quality and training | 20. Training carried out in the MOSU. |

| 21. Quality indicators used in the MOSU. | |

| Home-based follow-up | 22. Do you carry out postoperative follow-up of patients? If so, which? |

| 23. Periodic evaluation of pain at home by the patient. | |

| 24. Postoperative pain monitoring by the MOSU. | |

| 25. Adherence of surgical services to analgesia protocols. | |

| 26. Figure in charge of developing analgesia protocols at the MOSU. | |

| 27. Periodicity of reviews of analgesia protocols in the MOSU. | |

| 28. Would you consider an app useful with which the patient can monitor postoperative pain at home and integrate the information into the medical history? | |

| 29. Do you think that the use of an app would improve patients’ pain control? |

MOS: major outpatients surgery; MOSU: Major Outpatients Surgery Unit.

Statistical analysis was performed with SAS® software (version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The qualitative variables were described using absolute and relative frequencies, and the quantitative variables were described using the mean, standard deviation, confidence interval associated with the 95% mean, median, 25th percentile, 75th percentile, minimum value and maximum value. Missing data were considered lost.

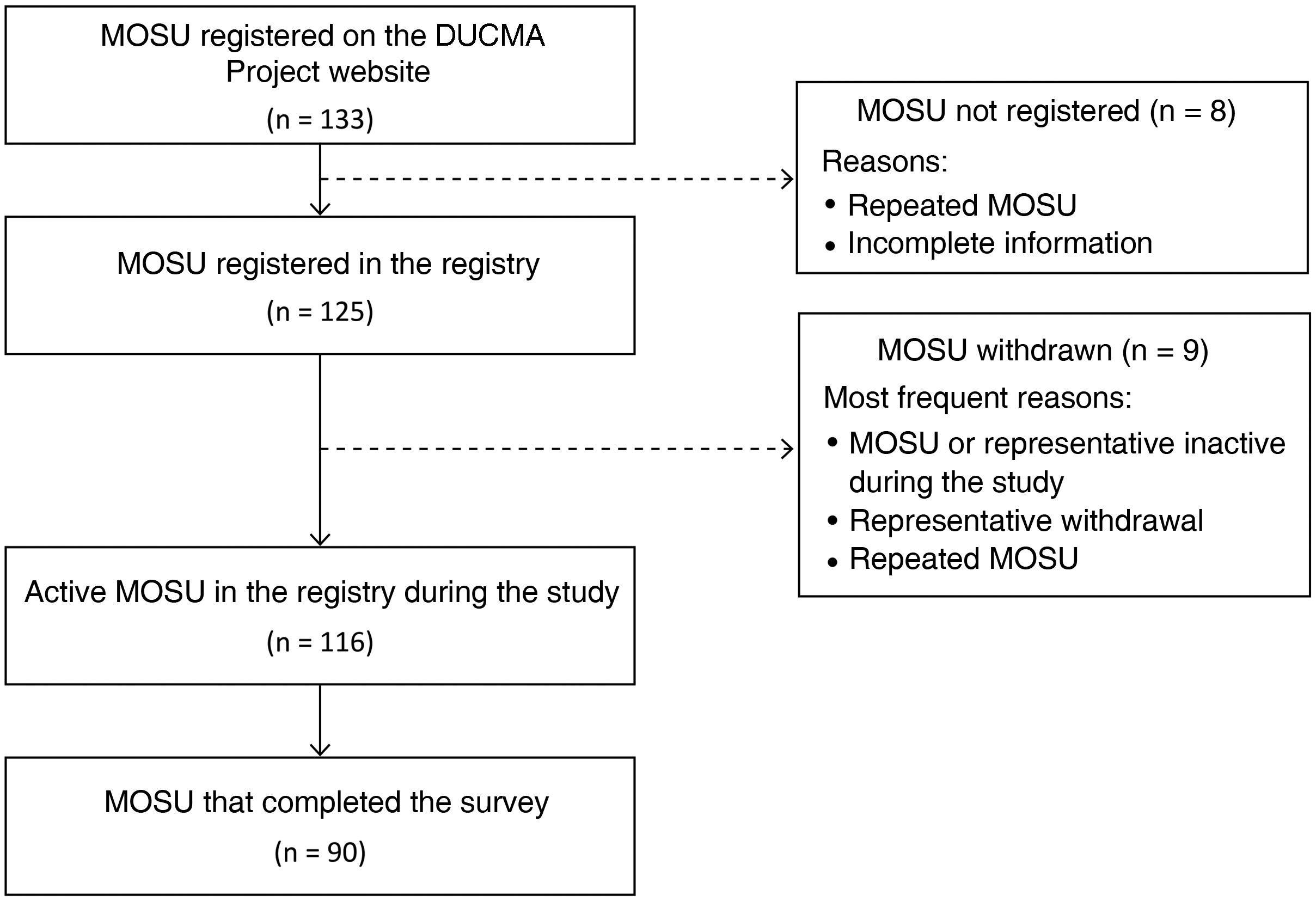

ResultsA total of 133 MOSUs registered on the DUCMA project website and 90 completed the survey (Fig. 1).

The ACs with greater representation were Catalonia (n = 22; 24%), the Community of Madrid (n = 14; 16%) and Andalusia (n = 12; 13%). The rest of the communities that registered at least one MOSU had a representation of less than 6% and no MOSU from Murcia, La Rioja, Ceuta and Melilla recorded data in the study. The participating MOSUs by AC are shown in Fig. 2.

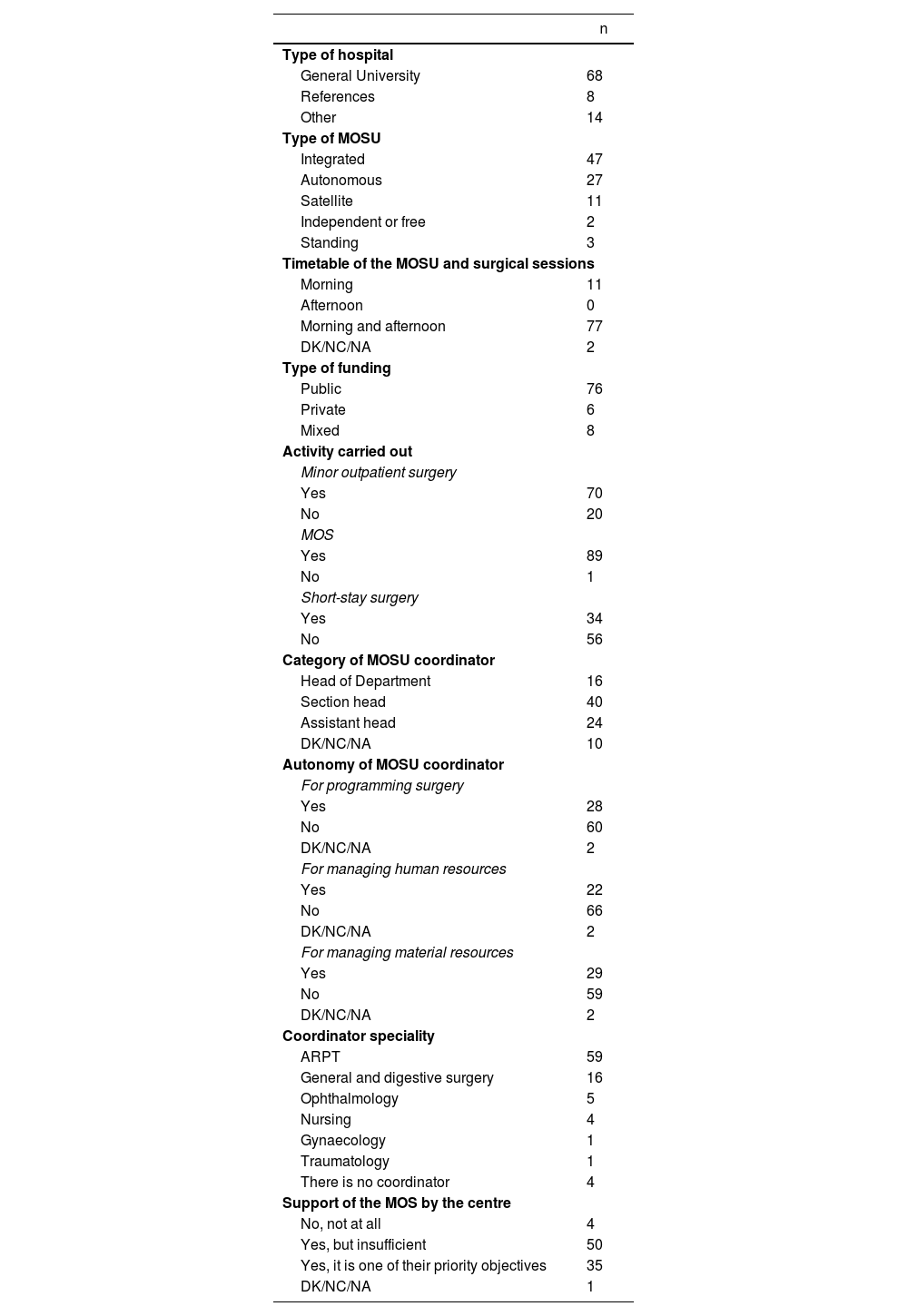

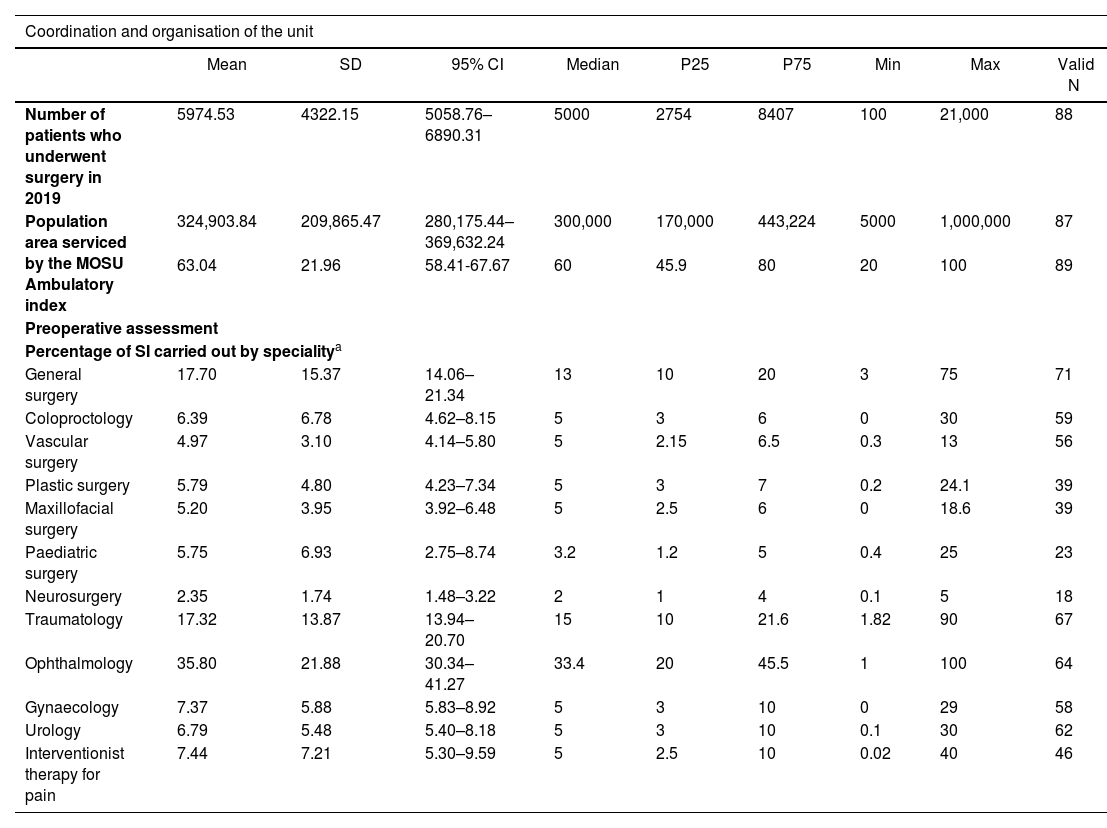

Coordination and organisation of the unitTables 2 and 3 respectively show the results of the qualitative and quantitative variables used to evaluate the coordination and organisation of the SUs.

Results of the qualitative variables used to evaluate the coordination and organisation of the MOSU (N = 90).

| n | |

|---|---|

| Type of hospital | |

| General University | 68 |

| References | 8 |

| Other | 14 |

| Type of MOSU | |

| Integrated | 47 |

| Autonomous | 27 |

| Satellite | 11 |

| Independent or free | 2 |

| Standing | 3 |

| Timetable of the MOSU and surgical sessions | |

| Morning | 11 |

| Afternoon | 0 |

| Morning and afternoon | 77 |

| DK/NC/NA | 2 |

| Type of funding | |

| Public | 76 |

| Private | 6 |

| Mixed | 8 |

| Activity carried out | |

| Minor outpatient surgery | |

| Yes | 70 |

| No | 20 |

| MOS | |

| Yes | 89 |

| No | 1 |

| Short-stay surgery | |

| Yes | 34 |

| No | 56 |

| Category of MOSU coordinator | |

| Head of Department | 16 |

| Section head | 40 |

| Assistant head | 24 |

| DK/NC/NA | 10 |

| Autonomy of MOSU coordinator | |

| For programming surgery | |

| Yes | 28 |

| No | 60 |

| DK/NC/NA | 2 |

| For managing human resources | |

| Yes | 22 |

| No | 66 |

| DK/NC/NA | 2 |

| For managing material resources | |

| Yes | 29 |

| No | 59 |

| DK/NC/NA | 2 |

| Coordinator speciality | |

| ARPT | 59 |

| General and digestive surgery | 16 |

| Ophthalmology | 5 |

| Nursing | 4 |

| Gynaecology | 1 |

| Traumatology | 1 |

| There is no coordinator | 4 |

| Support of the MOS by the centre | |

| No, not at all | 4 |

| Yes, but insufficient | 50 |

| Yes, it is one of their priority objectives | 35 |

| DK/NC/NA | 1 |

ARPT: anaesthesia, resuscitation and pain therapy; MOS: major outpatient surgery; DK/NC/NA: does not know/no comment/does not apply; MOSU: Major Outpatient Surgery Unit.

Results of the quantitative variables used to evaluate the coordination and organization of the MOSU and the preoperative assessment.

| Coordination and organisation of the unit | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | 95% CI | Median | P25 | P75 | Min | Max | Valid N | |

| Number of patients who underwent surgery in 2019 | 5974.53 | 4322.15 | 5058.76–6890.31 | 5000 | 2754 | 8407 | 100 | 21,000 | 88 |

| Population area serviced by the MOSU Ambulatory index | 324,903.84 | 209,865.47 | 280,175.44–369,632.24 | 300,000 | 170,000 | 443,224 | 5000 | 1,000,000 | 87 |

| 63.04 | 21.96 | 58.41-67.67 | 60 | 45.9 | 80 | 20 | 100 | 89 | |

| Preoperative assessment | |||||||||

| Percentage of SI carried out by specialitya | |||||||||

| General surgery | 17.70 | 15.37 | 14.06–21.34 | 13 | 10 | 20 | 3 | 75 | 71 |

| Coloproctology | 6.39 | 6.78 | 4.62–8.15 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 30 | 59 |

| Vascular surgery | 4.97 | 3.10 | 4.14–5.80 | 5 | 2.15 | 6.5 | 0.3 | 13 | 56 |

| Plastic surgery | 5.79 | 4.80 | 4.23–7.34 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 0.2 | 24.1 | 39 |

| Maxillofacial surgery | 5.20 | 3.95 | 3.92–6.48 | 5 | 2.5 | 6 | 0 | 18.6 | 39 |

| Paediatric surgery | 5.75 | 6.93 | 2.75–8.74 | 3.2 | 1.2 | 5 | 0.4 | 25 | 23 |

| Neurosurgery | 2.35 | 1.74 | 1.48–3.22 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 0.1 | 5 | 18 |

| Traumatology | 17.32 | 13.87 | 13.94–20.70 | 15 | 10 | 21.6 | 1.82 | 90 | 67 |

| Ophthalmology | 35.80 | 21.88 | 30.34–41.27 | 33.4 | 20 | 45.5 | 1 | 100 | 64 |

| Gynaecology | 7.37 | 5.88 | 5.83–8.92 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 29 | 58 |

| Urology | 6.79 | 5.48 | 5.40–8.18 | 5 | 3 | 10 | 0.1 | 30 | 62 |

| Interventionist therapy for pain | 7.44 | 7.21 | 5.30–9.59 | 5 | 2.5 | 10 | 0.02 | 40 | 46 |

95% CI: 95% confidence interval; Max: maximum value; Min: minimum value; P: percentile; MOSU: Major Outpatient Surgery Unit; SD: standard deviation; SI: surgical intervention.

Twenty-two MOSUs indicated that they receive primary care patients (mean 29%), 89 that they see patients referred from surgical specialists (mean 88%), and 29 that they see patients referred from nonsurgical specialties (mean 15%).

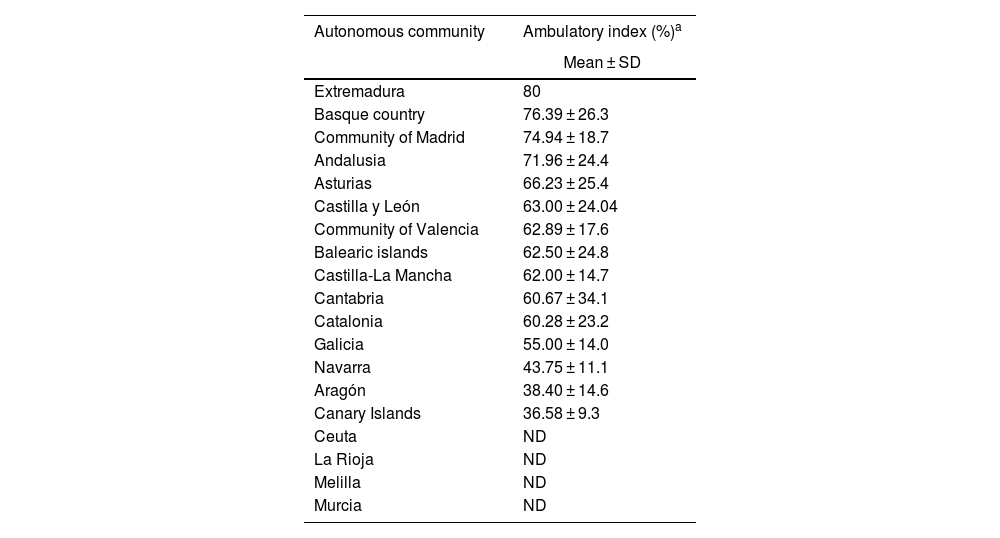

The global AI for Spain is shown in Table 3 and the differences observed between the ACs are presented in Table 4.

Ambulatory index by autonomous community.

| Autonomous community | Ambulatory index (%)a |

|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | |

| Extremadura | 80 |

| Basque country | 76.39 ± 26.3 |

| Community of Madrid | 74.94 ± 18.7 |

| Andalusia | 71.96 ± 24.4 |

| Asturias | 66.23 ± 25.4 |

| Castilla y León | 63.00 ± 24.04 |

| Community of Valencia | 62.89 ± 17.6 |

| Balearic islands | 62.50 ± 24.8 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 62.00 ± 14.7 |

| Cantabria | 60.67 ± 34.1 |

| Catalonia | 60.28 ± 23.2 |

| Galicia | 55.00 ± 14.0 |

| Navarra | 43.75 ± 11.1 |

| Aragón | 38.40 ± 14.6 |

| Canary Islands | 36.58 ± 9.3 |

| Ceuta | ND |

| La Rioja | ND |

| Melilla | ND |

| Murcia | ND |

ND: no data; MOSU: Major Outpatient Surgery Unit; SD: standard deviation.

Table 3 shows the results of the quantitative variables used to evaluate the preoperative assessment carried out in the MOSU, as well as the different integrated specialties.

Pain controlEighty per cent indicated that they have analgesia protocols adapted to surgical procedures. Furthermore, all MOSUs consider hemodynamic stability a necessary criterion for discharge. Other most valued criteria are minimal surgical bleeding and temporal-spatial orientation (98% surveyed).

Quality and trainingOf the 85 MOSUs that answered the questions about training and quality indicators used, 51% reported that their unit provides specific training for doctors and 55% provide it for nursing staff. Regarding the most used quality indicators, 87% use the suspension/cancellation rate, 80% the unplanned admission rate, 78% the postoperative telephone call, 69% the replacement rate and 67% the quality survey perceived by the patient.

Home-based follow-upOf the 84 MOSUs that answered these questions, 91% indicated that they perform postoperative follow-up. Among them, 93% call the patient by phone within 24 h, and 12% go personally to the patient’s home.

DiscussionThe results of the DUCMA 2.0 study provide an overview of the current state of MOS in Spain, defined by the International Association of Ambulatory Surgery (IAAS) as the type of surgery where discharge takes place on the same working day as the intervention, excluding the possibility of overnight stay.10 Including the possibility of an overnight stay falsifies the concept of MOS in the statistical data1 and this circumstance may be favoured when short-stay surgery is performed (with an overnight stay), as is the case in 38% of the MOSUs in the present study.

The majority of participating MOSUs belong to publicly funded General University Hospitals, with a median of 5000 patients operated on and population areas of 300,000 inhabitants, although the standard deviation is broad and includes centres with reference areas between 5000 and 1,000,000 population. ACs such as Catalonia, Madrid and Andalusia, are widely represented, but not all of them participated in the study, which generates bias.

The IAAS recommends promoting autonomous or satellite units as they are more cost-effective than integrated units.10 However, in Spain integrated type MOSUs predominate (52%), which share operating rooms in the central surgical block and with conventional inpatient surgery. This increases cancellations and can distort flow, an important point to improve in the future.

Two out of three coordinators are anaesthetists, but in 4% of MOSUs the coordination falls to the nursing staff. This data was already confirmed in the 2013 study, representing an innovative aspect in the management of MOSUs, since, in 18% of the units evaluated, the nursing staff was in charge of authorising patient discharge.3 Also striking is the absence of management autonomy in terms of preparation of surgical programming (67%), human resources (73%) and material resources (66%), which possibly derives from the fact that MOSU are integrated. However, 85% of MOSUs feel supported by the centre’s management.

According to global activity, Ophthalmology predominates (36%), followed by General and Digestive System Surgery (18%), which coincides with the literature.2,10 The referral of patients is carried out mainly from surgical specialists (88%), although it is worth highlighting a referral of 22% from primary schools. This may be due to collaboration experiences with them, such as the Kirubide Project.11 Sixty-six per cent of MOSUs make a call 24 h before the intervention for verification purposes and to give instructions to the patient, in line with the results of our previous study.3

As a fundamental aspect, our AI was 63%, in contrast to the 47.6% reported by the Ministry in 2021.4 Although it is evident that the AI show how a hospital centre and the health system in general function,1,6,7 the data diverge. This may be due to how the different ACs report the data that is then processed by the Ministry.12 Despite a progressive increase in the Ministry’s figures, 4,8,9,12 we are still far from other countries around us, such as Denmark (91%) or Norway (64%), although other countries, such as Italy or Portugal, do have an AI close to 50%.5 These differences are multi-factorial, and may include incentives from the financing systems, the organisation of the health system, the enthusiasm of the teams, the satisfaction of patients, and the data collection itself. 5,13,14 The reasons for the divergences between the DMOSU 2.0 study and the Ministry’s figures must be sought in the data collection process and the real MOS concept, as already mentioned.

There is great heterogeneity between the different ACs, both in our study and in the official data. Accepting the possible bias of the present study, those with the highest AI are Extremadura (although it only included one MOSU), the Basque Country, the Community of Madrid and Andalusia, all with values greater than 70%, while those with the lowest AI are Navarra, Aragon and the Canary Islands, the latter with 37%. For its part, the Ministry’s data from 20,214 places higher AI in Catalonia, the Community of Madrid and La Rioja (54.4%, 52.5% and 49.8%, respectively), and lower in Castilla y León, Extremadura and Aragón (37.9%, 36.3% and 36.0%, respectively), so the discrepancies are also evident. In the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the AI was lower than in 2019 (decrease in total surgical activity of 25% in public hospitals and 17% in private hospitals), but the strengthening of the MOSUs with strict measures to protect patients and health personnel contributed essentially to alleviating this decline.15

The discharge criteria used are based on scales derived from that of Aldrete.16 In our study, 80% of MOSUs have pain protocols, and four out of five MOSUs have analgesia protocols adapted to the type of surgical intervention. Insufficient attention to this symptom can lead to significant adverse effects and a low level of patient satisfaction.2,7

Half of the MOSUs provide specific training for doctors or nursing staff. These data confirm the observations of the 2013 study and show room for improvement.3 The training of physicians and nursing staff is essential for greater quality of care.17

Home-based follow-up is carried out by means of a postoperative call from the unit (91%), but only 57% offer the possibility of contacting the responsible physician, which suggests that the future of patient follow-up is probably related to telemedicine.18

The IAAS considers the use of clinical indicators essential to ensure a safe and efficient environment in MOS.19 In Spain, efforts have been made in this regard7,14,15,20,21,22 but, as in the 2013 study,3 they are not widely used. Scientific-technical quality indicators such as suspensions and the rate of unplanned admissions stand out in our study, and only two out of three MOSUs include perceived quality.

The main limitation of the study is that it is based on a voluntary survey and some questions are subjective in nature. The hospital structure in our country in 2019 had 308 MOSU in public centres and 234 in private centers.8

In conclusion, this study shows various aspects of the current situation of the MOS in Spain. It seems clear that greater coordination between administrative entities is needed to obtain reliable data and promote a real and effective increase in AI. Against this backdrop, it is essential to promote the existence of quality management systems in MOSUs and the training of the professionals involved.

FundingThis study did not receive any type of funding.

Conflict of interestsNone.

To all Units participating in the study, Laboratorios Menarini, Adknoma Health Research and Kalispera Medical Writing.