The implementation and generalized use of Ambulatory Surgery worldwide is currently a clear reality. Its progressive growth is expected in the short term, but this globalization can also negatively affect the education and training of future doctors, as well as those who are being trained now, if it is not standardized and regulated, since a significant part of the management of the most common pathology that could be performed in Ambulatory Surgery is completed outside the training circuits of hospitals where resident doctors are trained.

La implantación y generalización a nivel mundial de la Cirugía Mayor Ambulatoria es una realidad patente en la actualidad y se espera un crecimiento progresivo de la misma a corto plazo, pero esta globalización también puede afectar de forma negativa a la docencia y el entrenamiento de los futuros médicos y aquellos que están en formación, si no se estandariza y regula, ya que una parte importante de la gestión de la patología más frecuente subsidiaria de ser realizada en Cirugía Mayor Ambulatoria, acaba fuera de los circuitos del hospital donde el médico residente se está formando.

Ambulatory Surgery (AS) is defined by the International Association for Ambulatory Surgery (IAAS)1 as a surgical procedure or operation where the patient is discharged on the same day of surgery, excluding office procedures as well as minor and outpatient surgery. AS is the surgical method of choice for more than 85% of pathologies treated by a surgery department. Over time, and with scientific evidence, AS has clearly been shown to be a safe, effective and efficient system to resolve the processes included in a surgery unit portfolio.2–6

A correctly functioning healthcare system is based on 2 pillars, and both are necessary for its own existence and survival: guaranteed funding, and proper training of the healthcare professionals who sustain it.7

What is clear is that it is necessary to prioritize clinical management units that have a high rate of activity in ambulatory surgery and demonstrate their efficiency and effectiveness on a daily basis.8 In many cases, this was done during the most critical phase of the SARS-CoV-2 virus pandemic, and these units were quick and agile in understanding that the pandemic itself also presented a great opportunity for change and improvement, realizing that a correctly implemented AS regimen avoid traps and shortcuts that generate longer hospital stays and higher costs.9

Training in AS is equally important since it represents the pillar of quality patient care. However, while training seems more defined in other areas of surgery, only abdominal wall surgery programs refer to specific training in AS.10 Meanwhile, no references are made to such education in other areas, and current surgical training programs11 only provide AS training in certain countries.12 Occasionally, regulated AS training programs are organized with other specialties, such as anesthesia,13 but these result in confusion and lack of knowledge about what AS training is and should be like,14 particularly in our setting. We must not forget that training should be prioritized as a strategic line at any level of care. Likewise, such training should be generalized both regionally and nationally.

Thus, it seems timely for the Ambulatory Surgery and Postgraduate Training Divisions of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (Asociación Española de Cirujanos, or AEC) to provide a series of proposals and reflections about how to train our surgeons in order to treat patients with the highest levels of guaranteed safety in ambulatory surgery, and how hospital administrators can promote and encourage the development of training programs.

Idiosyncrasies of training in ambulatory surgery. What makes AS training different?Training in AS entails a series of connotations that clearly make it different from training in other areas of surgery.

First of all, the classic concept of the doctor-patient relationship is fragmented because the patient is discharged on the day of surgery. Therefore, there is no daily follow-up on the ward, although of course the patient is followed up while at home. This should not pose a problem, since the work overload often means that it is not possible for the doctor who initially treats the patient in the consultation and adds the patient to the waiting list to be present throughout the entire process.

In addition, the great advantage for students and resident doctors is the possibility to directly care for and monitor patients from surgery until discharge.

If we consider AS unit types at different hospitals, this represents a handicap for rotating residents because satellite units are outside the hospital area, and they may feel that other training activities will be missed. Paradoxically, their training is more likely to benefit since they are generally independent clinical management units with better structured organization, where resident doctors and medical students will be able to benefit from pre- and postoperative consultations. Also, despite the fact that it is not the ideal place for treating wounds, it is ideal for the acquisition of knowledge and skills in the clinical management of AS, which has intrinsic peculiarities.

Finally, we must remember that, in its beginnings, AS was predicted to be exclusively for very expert surgeons, and it did not seem the ideal place for training.15 However, scientific evidence has shown that the AS unit is a suitable place for the training of both students and residents, as it does not alter their function or the results between residents and staff,16 and the degree of compliance with objectives in terms of knowledge, skills and approaches is satisfactory.17

Undergraduate trainingAll surgeons, regardless of their specialty, will be involved in AS at some point in their professional career. Thus, it is necessary to have a basic knowledge of patient selection criteria, care circuits, discharge criteria and postoperative follow-up, as well as the different indicators and quality standards, which are specific in the case of AS. Therefore, it is surprising that there are no unified teaching criteria at medical schools regarding these factors during the degree program. Moreover, and with few exceptions (such as the School of Medicine of Seville),17 the inclusion of the fundamentals of AS as part of the degree program for medicine in our country continues to be anecdotal, unlike the situation in other countries.18,19

We think that it would be advisable for AS training to begin at university and, in the case of the Degree in Medicine, during the initial contact of medical students with surgical pathology in order to acquire theoretical/practical training. Authors like Docobo at al17 prospectively evaluate medical students in their 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th years of training regarding their competence in surgical knowledge, skills and approach during their rotation through the AS unit, and these authors have shown its importance and usefulness in their training.

The suggested proposals for improving undergraduate training include:

- 1

Introduce medical students from the 3rd year onward to the founding principles of AS.

- 2

Knowledge of basic management and quality concepts, especially those related with AS: replacement rate, outpatient rate, admission rate, cancellation rate, etc.

- 3

The concept of AS itself introduces students to the concepts of multidisciplinary work, teamwork, benchmarking and professional interrelation, especially with Primary Care.

- 4

Rotation of students through the AS unit, if the hospital has one, or in the different clinical units of the surgery departments in which pathologies are treated under the AS regime, both during their rotations throughout the degree and, if possible, 2–4 weeks during the last year of the degree, depending on how rotations are organized, with a series of assigned tasks that are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.Tasks for undergraduate students.

Tasks for undergraduate students during their rotation in the ambulatory surgery unit - -

Receive patients

- -

Follow up patients during their stay in the unit

- -

Attend the AS consultation

- -

Assist in the surgical interventions of the unit

- -

Postoperative monitoring and postoperative follow-up of patients

- -

Participate in activities of the unit: clinical and programming sessions

- -

Register activity in a surgical practice logbook

- -

- 5

Begin to involve students in the scientific and research activities of the unit, encouraging final degree projects about AS, while highlighting the importance of its transversality.

- 6

Generate a change in the mentality of both educators and students, so that they become excited about the AS type of surgical management. When medical schools talk about laparoscopy and robotic approaches, the concept of ambulatory surgery should be closely associated, since this in itself embodies innovation and progress.20

For years, scientific evidence has made it clear that AS units are an appropriate setting for training residents,12,20 and residents also share this opinion when asked. In Spain, however, there is no specific surgery resident training path focused on AS,21,22 and the current surgical specialty program11 only refers to the fact that training in AS must begin in the second year of residency in the form of courses and seminars, but no rotations are mentioned, nor is a specific time during residency identified. Unfortunately, training programs have often not been updated as advances have been made in surgery, which is why we insist on the opportunity to offer recommendations to consider when future changes or modifications are made to these programs.

Different models have been proposed for training in AS,23 including a model that considers it a rotation in the context of the training program, or continuous training throughout the entire residency, or a mixed training model that contemplates an initial rotation and continuous training throughout the entire residency, which seems the most reasonable option.

Stone24 proposed a series of current guidelines for resident training:

- 1

Provide specific instruction on how and when to prepare patients for AS, with a rotation in the unit that includes consultations.

- 2

Convey to residents the importance of reducing the postoperative stay in terms of reducing the risk of surgical infection, reducing costs and benefiting from the satisfaction of patients who are able to spend the night at home on the same day of the procedure.

- 3

Promote the concept of interactive teamwork with other services and units, as well as a broad relationship with Primary Care.

- 4

Help residents learn communication skills, especially with patients to ensure that they perfectly understand the instructions received about their treatment.

- 5

Ensure that residents actively participate in patient discharge and postoperative follow-up decisions.

- 6

Provide proper training for trainers: Continuing Education

Considering the current competency-based teaching model that requires adaptation to the characteristics of each medical center and the possibility of rotations in external units or centers in the event that hospitals do not have specific AS units or that their activity in this area is limited (which is done in different areas of surgical training and facilitated with grants for fellowships, such as those offered by scientific societies like AEC, following a mixed teaching model), we suggest a rotation of about 3–4 months during the second year of residency along with continued training throughout. As indicated in the training program, 2nd-year residents can take a basic training course in AS during their rotation (or prior to it). To date, the AEC and the Ambulatory Surgery Division have already conducted 6 online courses, which have been widely accepted and received much interest.25 In addition, AS has a very important characteristic, which is its transversality, so the knowledge acquired about AS is applicable to most rotations in other units during residency.

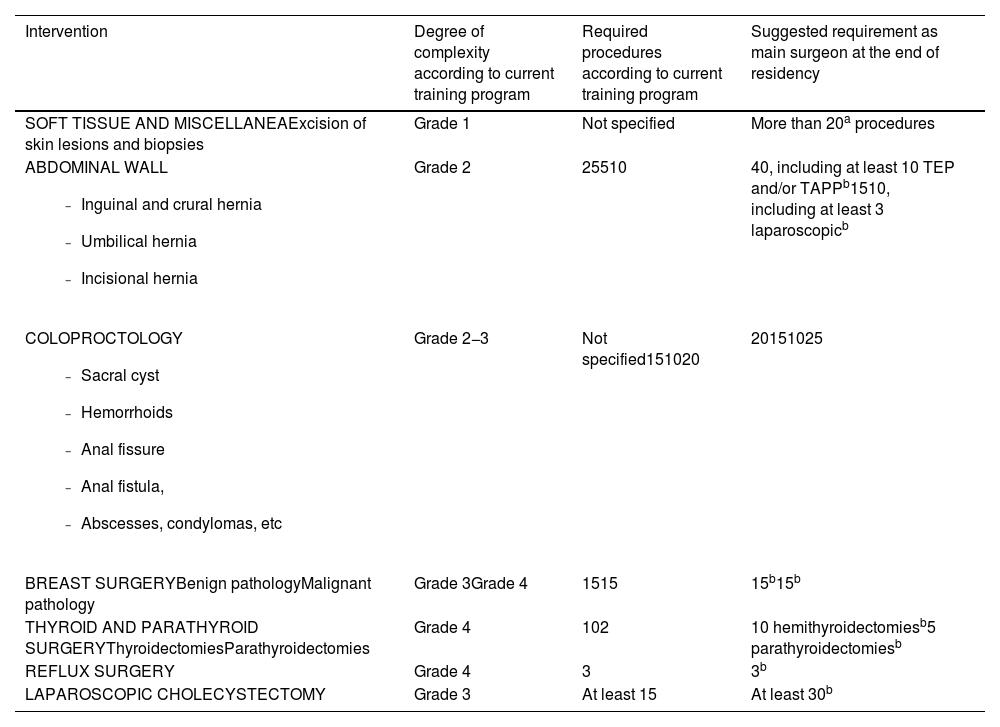

This professional competence in AS is based on the acquisition of a series of knowledge, skills and approaches that are listed in Table 2. In addition, it may be helpful to estimate a number of surgical interventions that would be mandatory for residents during their training period, which in some cases is stipulated by specialty training programs,11 but no mention is made for AS regimes. Hence, suggestions are proposed in Table 3, although it is very important to understand that these are recommendations that must be adapted to the setting of each hospital and/or AS unit itself. Surgeries like inguinal hernia repair are mostly performed in AS, but other pathologies are also very prevalent, such as cholelithiasis, in which the role of the laparoscopic approach is unquestionable. The fact that residents are and should be very involved is not included in AS service portfolios of many hospitals in our country, but their involvement in surgery services is a daily occurrence.

Competence of residents in ambulatory surgery.

| Competence in knowledge | Competence in skills | Competence in approach |

|---|---|---|

| A. ESSENTIAL KNOWLEDGE-Concept and definitions of AS-Indicators of AS-Inclusion and exclusion criteria-AS discharge criteria-Treatment circuits-Portfolio of services-Planning and scheduling treatment-Criteria of quality care-How to approach and treat complicationsB. BASIC KNOWLEDGE-Appropriate surgical technique given the portfolio of services and rotation-Management of nausea, vomiting and pain-Patient rights and responsibilities-User-level computer skills-Evidence-based medicine-Quality methodology-Research methodology-Resource management-Process management-Basic life support-Intermediate level of EnglishC. OPTIONAL KNOWLEDGE-Advanced life support-Training in prevention of occupational hazards-Bioethics in research-Information and communication technologies | A. ESSENTIAL SKILLS-Basic surgical procedures in AS and according to the portfolio of services: abdominal wall, proctology, breast, gallbladder, soft tissue-Diagnostic and instrumental tests-Ability to communicate within the unit and with different levelsB. BASIC SKILLS-Surgical and instrumental techniques-Management of intrahospital information systems-Continuous and comprehensive view of the processes-Creation of guidelines and/or collaboration in producing clinical practice guidelines and protocols in AS-Adequate use of available resources and time management-Ability to teach-Use of telemedicine systemsC. OPTIONAL SKILLS-Surgical procedures-Ability to teach-Application of basic research techniques-Social networking skills | -Involved with the surgical team and unit-Available for research and teaching-Relationship with the team and patients-Involvement in complaints-Patient care, teaching, research, management |

Ambulatory surgical procedures.

| Intervention | Degree of complexity according to current training program | Required procedures according to current training program | Suggested requirement as main surgeon at the end of residency |

|---|---|---|---|

| SOFT TISSUE AND MISCELLANEAExcision of skin lesions and biopsies | Grade 1 | Not specified | More than 20a procedures |

ABDOMINAL WALL

| Grade 2 | 25510 | 40, including at least 10 TEP and/or TAPPb1510, including at least 3 laparoscopicb |

COLOPROCTOLOGY

| Grade 2−3 | Not specified151020 | 20151025 |

| BREAST SURGERYBenign pathologyMalignant pathology | Grade 3Grade 4 | 1515 | 15b15b |

| THYROID AND PARATHYROID SURGERYThyroidectomiesParathyroidectomies | Grade 4 | 102 | 10 hemithyroidectomiesb5 parathyroidectomiesb |

| REFLUX SURGERY | Grade 4 | 3 | 3b |

| LAPAROSCOPIC CHOLECYSTECTOMY | Grade 3 | At least 15 | At least 30b |

It is likewise important to understand that, whenever we talk about professional competence, assessment tools are necessary. Several acceptable and appropriate models have been developed with this objective, such as exams, rotation evaluation sheets, objective clinical exams (ECOE), 360º evaluation, and currently the very useful tool of clinical simulation.26 And like any training tool, both formative and summative, an element of feedback must be included to highlight the resident’s strengths, suggesting improvements, and developing plans of action to improve. All this information, which is measurable, must be collected in a registry that should be universal and unified for all surgery residents in our country. In our opinion, the resident surgical electronic logbook27 seems the most appropriate.

In this way, these skills must be transmitted during the professional activity, while promoting teamwork significantly as well as progressively assuming more responsibilities.

Continued training in ASContinued training is a necessity and an obligation to stay updated on new indications, procedures added to the service portfolio, and surgical techniques, and to be able to evaluate their results.

Attending courses,25 experimental training and clinical simulation centers,26 and meetings and conferences organized by scientific societies7 as well as the completion of master programs, such as the one offered by the Spanish Association of Major Ambulatory Surgery (ASECMA),28 represent the appropriate way to achieve this training. At the same time, the pandemic has taught us that serious situations can become opportunities for change;5 it has become clear that, although there were no in-person activities, teaching was maintained through webinar-type online platforms, which are here to stay and are very useful today.

The appearance of training platforms that facilitate learning among healthcare professionals, such as RED AEC or AEC Connect, and their dissemination through social media have radically changed the way information is transmitted. Results can be communicated in real time through #SoMe4Surgery, which has interconnected millions of surgeons across the world in record time. AS is also present on different social media accounts (such as @cma_aecirujanos or @AmbMe4), which have updated information and all the news related to AS.

A final step in AS training could be the accreditation of clinical management units, and for this it is necessary to previously know the current situation of AS units. ASECMA is working on the DUCMA project (Registry of Ambulatory Surgery Units), which will be able to provide an overview of their real situation. Currently, there is no European Board endorsed by the European Union of Medical Specialists (UEMS) specifically for AS, but there are for different areas of training closely linked to it. This may be an appropriate route for the certification of professionals29 and for the future development of training units and programs.

ConclusionsAmbulatory Surgery, as a strategic pillar of the National Health System, must be known by all medical professionals, starting in medical school and implemented during residency. Thus, Primary Care physicians will have an understanding of AS circuits, and surgical professionals from the different surgical specialties will have received solid training in the techniques and management of AS. Therefore, the need for a training itinerary aimed at this area is urgent, without forgetting the importance of continued training, to which all surgeons should have guaranteed access.

FundingThis work has not received any type of funding

Conflict of interestThere is no conflict of interest

Our thanks to Dr Jesús Badía for his help in preparing the suggestions for the surgical procedures, together with Dr Alberto López, Dr Belén Porrero, Dr Luis Tallón and Dr Victor J Ovejero, new members of the AS Division Board.