One of the most striking features of infection by SARS-CoV-2 – unlike other Beta-coronavirus (CoVs, SARS, MERS-coV) – is the development of thromboembolic complications1

The gastrointestinal thromboembolic complications of SARS-CoV-2 are associated with high mortality (32%–86%). We present the case of a patient with severe COVID-19 who developed infrarenal thrombosis and perforation of the colon.

A 79-year-old male was transferred to our center with severe bilateral pneumonia due to SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) and required mechanical ventilations. He had a history of acute myocardial infarction, hypertension, obesity (BMI 28), dyslipidemia and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. On admission his ASA (American Society of Anesthesiology) score was IV. Blood analyses revealed hemoglobin 11.7g/dL (Reference Range 13.6–17.0), leucocytes 16.9×109/L (RR 6–10) with 91% neutrophils, platelets 251×109/L (RR 150–450), d-dimer 1250ng/ml (RR 150–500), C reactive protein 4.6ng/dL (RR 0.0–0.50), ferritin 1171.1μg/L (RR<500μg/L), lactic acid 2.14 (RR<2).

He was on antithrombotic prophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), 5000 UI/1xd.

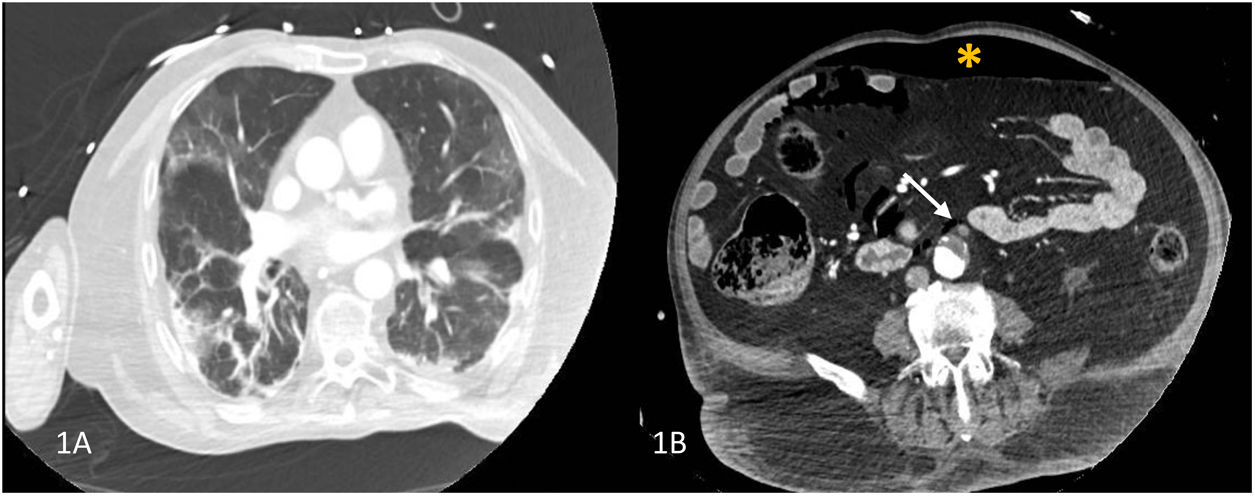

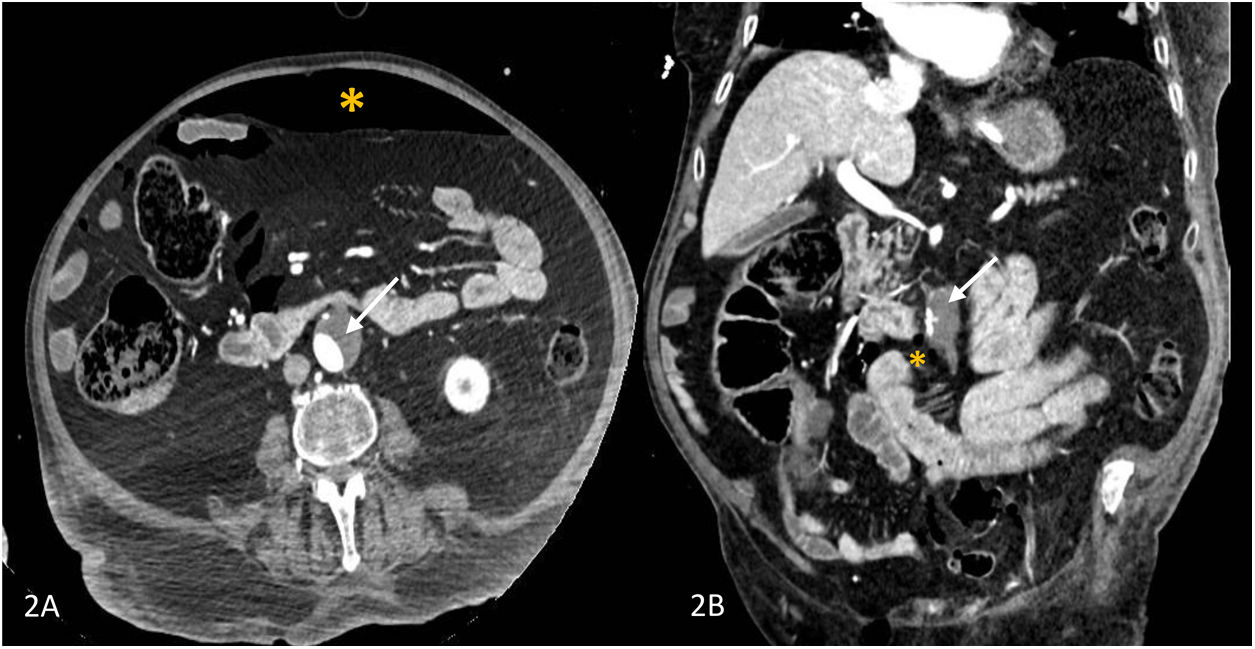

Given the deterioration in his neurological state on admission (delirium, mental confusion), cranial and pulmonary computed tomographic angiography (CTA) was performed which revealed bilateral pneumonia (Fig. 1A) and pneumoperitoneum as a result of which an abdominal CTA was performed which showed pneumoperitoneum, mural thrombosis of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) and infrarenal aorta respectively (Fig. 1B, Fig. 2A and B).

(A) Computed tomographic angyography (CTA) of the chest showing bilateral ground-glass opacities and bibasilar areas of consolidation. (B) CT-angiographic image showing a large mural thrombus extending from the infrarenal aorta into the inferior mesenteric artery (arrow) and pneumoperitoneum (asterisk).

The patient underwent surgery and perforation of the sigmoid colon with purulent peritonitis was identified and a Hartmann's procedure was performed. The patient progressed favorably after days in intensive care.

The histologic analysis revealed perforation of the colon associated with diverticulosis and a marked inflammatory reaction. A real time reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) of the RNA extracted from the formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded tissue confirmed the presence of RNA from SARS-CoV-2, N gene, generic N:30,71 in the wall of the colon.

The patient signed the informed consent for the publication of his clinical information and images.

One of the most striking phenomena in severe COVID-19 is the high incidence of venous and arterial thromboembolic complications in multiple locations, even when prophylactic doses of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) have been administered, a phenomenon which has recently been termed “COVID-19-associated coagulopathy” (CAC).1 This abnormality is characterized by increases in d-dimer, fibrinogen, von Willebrand factor (VWF) and factor VIII with normal platelet levels, prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) respectively.1

Recent studies have reported thromboembolic complications in 31% and 49% of COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care in spite of antithrombotic prophylaxis.2,3 In our case, thrombosis of the aorta and IMA was associated with perforation of the sigmoid colon with the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in the colon wall.

Several pathogenic mechanisms associated with thromboembolic complications and intestinal ischemia have been proposed. Firstly, vascular thrombosis would be due to the endothelial damage caused by SARS-CoV-2, thanks to the presence in the endothelium of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptors and of type II transmembrane serine proteases (TMPRSS-2) which facilitate the binding of SARS-CoV-2 to the membrane of the cell endothelium a phenomenon known as immune-thrombosis or thrombo-inflammation.1,4 Apart from the binding of viral proteins to the heparan sulfate, the endothelium loses its antithrombotic properties, a reduction in the synthesis of nitric oxide (NO) and an increase in angiotensin-II, which leads to procoagulant abnormalities.1,5

Secondly, direct injury of the mucosa of the intestine and colon has been reported by SARS-CoV-2, which is facilitated by the presence of abundant ACE2 and TMPRSS-2 membrane receptors in the intestine and colon.6,7 The cell damage and necrosis would induce the innate immune response (the so-called “cytokine storm”) secondary to the release of damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPS) and pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS), thus causing the synthesis of proinflammatory and prothrombotic cytokines.1,5,8

Finally, it cannot be ruled out that the perforation of the sigmoid colon might be due to the perforation of a diverticulum secondary to occlusive intestinal ischemia or non-occlusive ischemia resulting from abnormalities in perfusion.9

In spite of antithrombotic prophylaxis with LMWH and the recommendations of more than 70 scientific societies on antithrombotic prevention, in severe COVID-19 very often oligo-symptomatic (pauci-symptomatic) thromboembolic complications occur which require early diagnosis and treatment given their high morbidity and mortality.10

FundingNone declared.

Author contributionsStudy concept and design (AA, JAC, JB,), data collection and analysis (AA, JAC), manuscript preparation (AA, JAC), manuscript review (AA, VV, JAC, FR). All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Conflict of interestAll authors have no relevant conflicts of interest to report.