To describe the design and implementation of a Crisis Resource Management (CRM) training program for the initial assessment of polytrauma patients.

MethodsProspectively implemented CRM training program in acute-care tertiary hospital by hospital personnel involved in the care of polytraumatisms. The program has a blended format and 23-h duration, including 11 h of online theoretical training followed by 12-h simulation modules and practical cases devoted to the roles of members of the trauma team, functioning of the polytrauma room, and key aspects of teamwork. The Human Factors Attitude Survey (HFAS) was used to assess attitudes related to non-technical skills, and the End-of-Course Critique (ECC) survey to evaluate satisfaction with training. We evaluated changes in the pre- and post-training assessments.

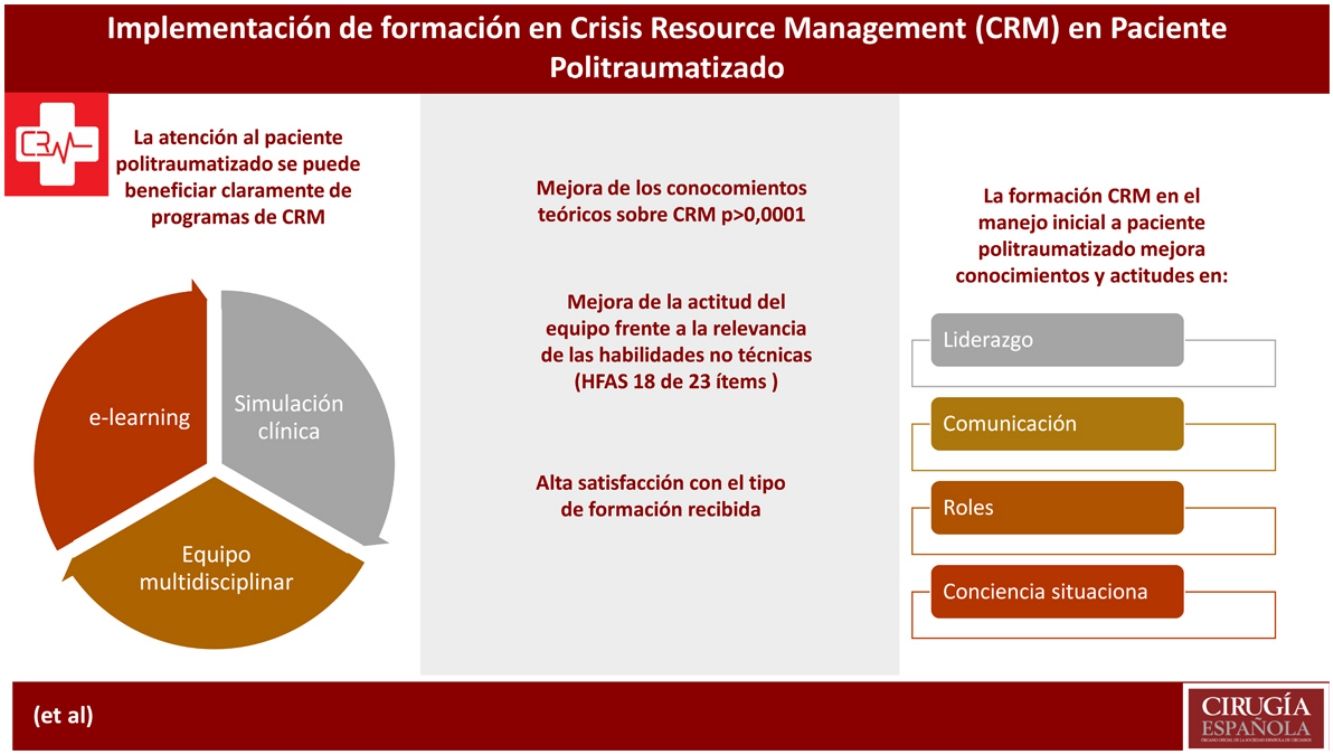

ResultsEighty staff personnel (26% specialists, 16% residents, 29% nurses, 14% nursing assistant, 15% stretcher bearer) participated in three editions of the program. Theoretical knowledge improved from a mean (SD) of 5.95 (1.7) to 8.27 (2.1) (P < .0001). In the HFAS, statistically significant differences in 18 of 23 attitudinal markers were observed, with improvements in all items of “leadership” and “roles”, in 4 of 5 items of “situational awareness”, and in 4 of 8 items of “communication”. Mean values obtained in the ECC questionnaire were also very high.

ConclusionsA CRM training model developed for the initial care of polytrauma patients improved theoretical knowledge and participants perceptions and attitudes regarding leadership, communication, roles, and situational awareness of members of the trauma team.

Describir el diseño y la implementación de un programa de formación basado en Crisis Resource Management para la evaluación inicial de los pacientes con politraumatismos.

MétodosImplementación prospectiva de un programa CRM de formación en Hospital terciario con el personal del hospital involucrado en la asistencia de politraumatismos. El programa tenía un formato semipresencial de 23 horas de duración, incluyendo 11 horas de formación online de contenido teórico seguidas de 12 horas de módulos de simulación y casos prácticos referidos a los papeles de los miembros del equipo de trauma, funcionamiento del box de trauma y aspectos claves del trabajo en equipo. El Human Factors Attitude Survey (HFAS) se utilizó para evaluar las actitudes relacionadas con las habilidades no técnicas y el End-of-Course Critique (ECC) cuestionario para valorar la satisfacción con la formación. Se evaluaron los cambios antes y después de la formación.

ResultadosOchenta miembros del hospital (26% especialistas, 16% residentes, 29% enfermeras, 14% auxiliares de enfermería, 15% camilleros) participaron en tres ediciones del programa. El conocimiento teórico aumentó de una media (DE) de 5.95 (1.7) a 8.27 (2.1) (P < ,0001). En el HFAS, se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en 18 de los 23 marcadores de actitud, con mejorías en todos los ítems de “liderazgo” y “roles”, en 4 de los 5 items de “consciencia situacional” y en 4 de los 8 ítems de “comunicación”. Los valores medios obtenidos en el cuestionario ECC tambien fueron muy altos.

ConclusionesUn modelo CRM de formación desarrollado para la atención inicial de los pacientes con politraumatismos mejoró el conocimiento teórico y las percepciones y actitudes de los participantes relacionadas con el liderazgo, la comunicación, los roles y la consciencia situacional de los miembros del equipo de trauma.

Medical errors are inherent features of any procedure or medical intervention, and it has been claimed that around 100,000 people in the U.S. die every year from medical errors1. A substantial percentage of these errors are caused by factors related to non-technical skills (NTS), encompassing interpersonal skills (e.g. communication, leadership, teamwork) and cognitive skills (e.g. situation awareness, decision making)1,2. It has been argued that Medicine presents parallels with high-hazard industries, mainly the aerospace sector, where since the 1970s training in NTS has been priorized through Crew Resource Management programs1,3. In the 1990s, Gaba et al.4–6 coined the term Crisis Resource Management (CRM) and adapted real-life simulation training programs to help acquire and develop skills in resource management and decision making during crises in practice. The set of principles dealing with cognitive and interpersonal behaviors that contribute to optimal team performance and decision making are especially useful for acute care specialties, such as critical care, emergency medicine, and anesthesiology in which healthcare professionals must treat severely ill patients, while facing diagnostic ambiguity, resource limitations, safety challenges, and numerous disruptions in turbulent work environments7–9.

The care of polytrauma patients meets all the criteria to benefit from CRM programs10. Standard training programs for polytraumatized patients, such as Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS®), have structured patient management undertaking primary and secondary assessments and constant reevaluation, but are focused on individual participants rather than considering that current care is provided by large and complex multidisciplinary teams11. Although adequate individual work performance is essential to the medical team, skills in group dynamics are necessary to complete tasks efficiently in critical dynamic situations7,11. In the last decade, some initiatives have been developed to ensure acquisition of NTS for the modern care of polytrauma patients, such as the Canadian nationwide Standardized Trauma and Resuscitation Team Training (S.T.A.R.T.T.)1, based on the implementation of CRM in multidisciplinary trauma teams showing a high level of participants’ satisfaction and increased team performance12. In the 10th edition of the ATLS®, a new teamwork section at the end of each chapter has been added as well as an appendix of trauma team resource management13.

Formal education of the medical team and a structured feedback have been recognized as effective approaches for improving group dynamics3. Also, there is increasing evidence that developing simulations in CRM training programs can improve communication within the team, distribution of tasks, and the subjective level of stress1,14. In this respect, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQL) has developed the TeamSTEPPS®15,16, an evidence-based teamwork system promoting integration of NTS to the delivery of quality health care and to preventing and mitigating medical errors and patient injury and harm17.

In 2017, the service of anesthesiology and resuscitation of a tertiary care reference hospital in Sabadell, Catalonia (Spain) promoted the implementation and evaluation of a specific CRM training program for the trauma team involved in the initial care of polytrauma patients, aimed to reinforce through theoretical concepts and simulation scenarios the clinicians’ knowledge and skills in trauma practice. The objective of the present study was to assess changes in knowledge acquisition and attitudes towards the importance of human factors after implementation of the CRM course for the care of severely injured patients.

Material and methodsA specific CRM training program for the medical team involved in the initial care of polytraumatized patients was designed, and included in the internal training activities of the hospital since 2018. Our center, Corporació Sanitària Parc Taulí is an 860-bed tertiary care teaching hospital located in the city of Sabadell (≈220,000 inhabitants, 2021 census), 20 km north of Barcelona in Catalonia (Spain). Approximately 550 polytraumatized patients are attended each year, 160 of which require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).

The program was designed according to the S.T.A.R.T.T. training model1,12 and the integration of the principles of CRM to team dynamics as outlined in the Trauma Crisis Resource Management Manual of Gillman et al.18. The course was designed and taught by medical experts in the care of polytraumatized patients and instructors in clinical simulation. It has a blended format and 23-h duration, including 11 h of online theoretical training, in which previous knowledge of participants was evaluated, followed by modules of classes and visualization of practical cases devoted to the roles of members of the trauma team, functioning of the polytrauma room, and key aspects of teamwork, such as leadership, roles, communication, and situational awareness.

Simulation training was performed using a SimMan 3 G mannequin (Laerdal Medical Ltd., Orpington, UK) in an adapted environment simulating a trauma room for the care of polytraumatized patients. Participants attended 12-h simulation training and were divided into groups of 7 persons, with the actual distribution of places of a trauma team of our center (1 team leader, 1 anesthesiologist, 1 general surgeon, 1 traumatologist, 2 registered nurses, 1 nursing assistant, and 1 stretcher bearer). Each practical session was performed by the two groups, each one performing a total of 5 simulation exercises and debriefings of eight exercises (the final exercises or exam did not have debriefings) as well as attending the exercises of the other group.

Three clinical scenarios were designed, including pelvic trauma and devastating injuries of the lower extremity, severe cranioencephalic traumatism with associated thoracic trauma, and abdominal traumatism. These three scenarios were designed in such a way that participants should worked on transfer of the patient to the medical emergency service, request of complementary studies, establishment of tentative diagnoses, emergent treatments, and patient’s transfer to other services. The first scenario was used as baseline and final simulation activity, whereas the second and third scenarios were worked on in three different exercises by the groups of participants. In the first scenario, each participant assumed his/her real role, but in the second scenario, an exchange of roles was carried out within the same group with new roles were assigned by the teaching team, aimed at knowing different workloads and encouraging cross-monitoring and cooperation. Also, distracting factors were added (e.g. difficult intravenous access, the stretcher bearer leaving the trauma room for having finished the shift). In the third exercise, the team assumed the clinical scenario in which they had not been directly worked in the previous exercises, but they were attended debriefing of the other group; in this case, simulation with a blinded leader was carried out in order to improve intragroup communication.

Changes in the acquisition of knowledge based on the online theoretical training was evaluated using a multiple-choice 16-item questionnaire, which was designed ad hoc for the purpose of CRM training and had to be completed by participants before and after training. Each item had five alternative answers, of which exactly one was correct. Correct answers were score “1” and the final sum was divided by 16 and multiplied by 10, with a final score ranging between 0 and 10. Details of the questionnaire are available in the Supplementary material.

The Human Factors Attitude Survey (HFAS) was used to assess changes in attitudes related to team behavior emphasized in each module of the CRM training program (communication, leadership, roles, and situational awareness). This instrument was modified from an aviation-based attitudinal survey developed by the University of Texas and NASA19, and has been used in other studies to assess team behavior and communication among healthcare professionals17,19,20. The HFAS has a total of 23 items and is characterized by good internal reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.89). Participants were asked to indicate their agreement with each question on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, and 5 = strongly agree. The survey was administered before and after simulation training. All questions were adapted to the care of polytrauma patients and were reviewed by expert doctors and nurses for content and applicability to the study. Participants completed a 12-question End-of-Course Critique (ECC) survey designed to assess the perceived need for training, usefulness of CRM skill sets, and satisfaction with CRM training. The score of each question was also evaluated using a 5-point Likert scale. All questionnaires were anonymous. Data of the professional profile of participants were also recorded.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee (CEIC) (code 2018513, approval date February 11, 2018). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Statistical analysisCategorical data are expressed as frequencies and percentages, and continuous data as mean and standard deviation (SD). The Mann-Whitney U test for independent samples was used to assess differences between pre- and post-training changes. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Data analysis was performed using the SPSS software program (version 23.0) for Windows.

ResultsBetween January and December 2018, three editions of the CRM training course for polytrauma patients were carried out, with a total of 80 participants (68.7% women). The professional profile of participants is shown in Table 1. Twenty-one (26%) participants were specialists, 13 (16%) residents, 23 (29%) registered nurses, 11 (14%) nursing assistants, and 12 (15%) stretcher bearers.

Professional profile of 80 participants in the CRM training program.

| Profile | Number (%) |

|---|---|

| Specialist physician | 21 (26) |

| Anesthesiology | 13 (62) |

| Traumatology and orthopaedic surgery | 3 (14) |

| Pediatric surgery | 2 (10) |

| General surgery | 1 (5) |

| Intensive care medicine | 1 (5) |

| Pediatrics | 1 (5) |

| Resident physician | 13 (16) |

| Anesthesiology | 5 (38) |

| General surgery | 4 (31) |

| Traumatology and orthopaedic surgery | 3 (23) |

| Intensive care medicine | 1 (8) |

| Registered nurse | 23 (29) |

| Nursing assistant | 11 (14) |

| Stretcher bearer | 12 (15) |

Theoretical knowledge after the online training improved from a mean of 5.95 (1.7) to 8.27 (2.1) points (P < .0001). Analysis of the HFAS responses revealed statistically significant improvements in 18 of 23 attitudinal markers (Table 2). In the domains of “leadership” and “roles”, pre- and post-training comparisons for all questions were statistically significant. The two questions of the survey corresponding to “roles” achieved the highest post-training scores, with a mean of 4.85 (0.46) for “Prior to the procedure, it is important for all the team members to be familiar with the tasks and responsibilities of the other members of the team” and 4.83 (0.57) for “Team leader and team members can improve decision-making skills through training”. However, most of the questions corresponding to “leadership” were those with more marked pre- and post-training differences. The analysis of attitudes of the 8 questions regarding “communication” showed statistically significant differences in 4, whereas there were no significant changes in the remaining 4, particularly the question “The set-up process for a trauma (gown & glove, set up equipment) negatively affects communication” showed the lowest non-significant change, from a mean of 2.59 (1.63) to 2.84 (1.26).

Pre- and post-training results of the Human Factors Attitude Survey.

| Survey question | Pre-training mean (SD) | Post-training mean (SD) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Relevant information regarding the incoming trauma is provided by the personnel of medical emergencies before arrival of the patient | 3.85 (1.24) | 4.53 (0.60) | .001 |

| 2. The team leader is identified to the personnel of medical emergencies | 3.79 (1.25) | 4.67 (0.55) | < .001 |

| 3. Prior to the procedure, it is important for all the team members to be familiar with the tasks and responsibilities of the other members of the team | 4.05 (1.19) | 4.85 (0.46) | < .001 |

| 4. The team leader obtains relevant information from personnel of medical emergencies | 4.28 (0.88) | 4.63 (0.51) | .013 |

| 5. The team leader identifies him/herself to the team members | 3.83 (1.14) | 4.73 (0.55) | < .001 |

| 6. My performance is not adversely affected by working with an inexperienced or less capable team | 3.00 (1.26) | 3.25 (1.36) | .216 |

| 7. Team leader and team members can improve decision-making skills through training | 4.58 (0.64) | 4.83 (0.57) | .001 |

| 8. My ability to detect adverse situations has a direct relationship to the quality of decisions I make | 4.01 (0.89) | 4.52 (0.64) | < .001 |

| 9. It is important for me to be involved in a briefing before the patient arrives | 4.20 (0.95) | 4.77 (0.45) | < .001 |

| 10. I know what I am expected to do during a trauma before bedside care begins | 4.14 (0.86) | 4.51 (0.53) | .006 |

| 11. The team leader communicates a plan for the patient before the patient arrives | 3.28 (1.21) | 4.52 (0.68) | < .001 |

| 12. The team leader assigns roles before the patient arrives | 3.06 (1.18) | 4.33 (0.81) | < .001 |

| 13. In response to a critical unplanned event, the team leader should verbalize plans and ensure that the information is understood by all team members | 3.53 (1.25) | 4.47 (0.72) | < .001 |

| 14. The quality of communication before the patient arrives improves bedside care | 4.68 (0.57) | 4.82 (0.39) | .253 |

| 15. A discussion of alternative methods does not make the team leader appear indecisive | 3.59 (1.1) | 4.35 (0.82) | < .001 |

| 16. The number of persons in the trauma room negatively affects communication | 4.54 (0.82) | 4.62 (0.81) | .411 |

| 17. The noise level in the trauma room negatively affects communication | 4.70 (0.68) | 4.80 (0.69) | .082 |

| 18. I know the patient’s level of severity, mechanism of injury and relevant patient information before patient arrives | 3.60 (1.07) | 4.30 (0.79) | < .001 |

| 19. A constructive debriefing after the event is a crucial part of maintaining and developing effective team coordination | 4.35 (0.96) | 4.72 (0.48) | .017 |

| 20. The set-up process for a trauma (gown & glove, set up equipment) negatively affects communication | 2.59 (1.63) | 2.84 (1.26) | .236 |

| 21. When there are simultaneous traumas, roles of caregivers are assigned before patient arrives | 3.52 (1.26) | 4.28 (0.81) | < .001 |

| 22. If I perceive a problem with the patients, I say it loudly, independently regardless of the team member affected | 3.57 (1.21) | 4.17 (0.85) | .002 |

| 23. The staff taking care of a polytrauma patient need training to “speak up” when they see something that is not right | 4.25 (0.88) | 4.58 (0.65) | .017 |

Questions 1, 13, 14, 16, 17, 20, 22, and 23 are related to “communication”; questions 2, 4, 5, 11, 12, 15, 19, and 21 are related to “leadership”; questions 3 and 7 are related to “roles”; and questions 6, 8, 9, 10, and 18 are related to “situational awareness”.

Likert scale used: 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree; SD: standard deviation.

In relation to the final assessment of the perceived usefulness and satisfaction with the CRM training program, mean values obtained in the ECC questionnaire were very high (Table 3). The percentages of responses for a maximum score of 5 (strongly agree) ranged between 93.4% and 99% (Table 3).

Results of End-of-Course Critique (ECC) survey at the end of the CRM training.

| Questions | Mean (SD) | Percentage of responses over a maximum of 5 score* |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I had the need for this training/information | 4.76 (0.43) | 95.2 |

| 2. CRM training provided me with knowledge and/or skills | 4.81 (0.43) | 96.2 |

| 3. This training has the potential to increase patient safety and quality care | 4.95 (0.22) | 99 |

| 4. This training was useful to reduce errors in your practice | 4.90 (0.34) | 98 |

| 5. Is “leadership” training useful? | 4.85 (0.40) | 97 |

| 6. Is “situational awareness” training useful? | 4.84 (0.41) | 96.8 |

| 7. Knowing the roles of the team members and the distribution of material in the trauma room improves my performance | 4.92 (0.27) | 98.4 |

| 8. The team leader and team members may improve their skills with training | 4.91 (0.29) | 98.2 |

| 9. My ability to detect adverse situations has a direct relationship with the quality of decisions that I take | 4.67 (0.52) | 93.4 |

| 10. For me, it is important to be present in the briefing before arrival of the patient | 4.85 (0.40) | 97 |

| 11. Knowing the different communication tools is useful in my daily practice | 4.78 (0.47) | 95.6 |

| 12. This training will change the way I do things | 4.80 (0.40) | 96 |

CRM: crisis resource management; SD: standard deviation.

Implementation of the CRM training program focused on the initial care of polytrauma patients was associated with an improvement of NTS in the areas of leadership, roles, and situational awareness, as well as a significant improvement in the theoretical knowledge of human factors.21 In 1999, the publication of “To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System” by the Institute of Medicine22 emphasized the role of human errors in the clinical setting and proposed the application of crew CRM team-building communication process of the aviation industry to improve safety. Although specific training programs in polytraumatisms are starting to highlight the human factor as a key aspect in the management of polytrauma patients13, most emergency medicine caregivers currently receive not formal CRM training3. CRM objectives enhance communication for all team members, use of resources, situational awareness, leadership, and team strategies1. Similar to other programs, such as the Canadian S.T.A.R.T.T.1, the aim of our course was not to replace specific training on the management of polytraumatisms, rather than to apply CRM principles in the care of polytrauma patients in the trauma room setting following ATLS® management guidelines13. Although CRM training programs should be tailored to the characteristics and dynamics of each center, it is beneficial for multidisciplinary teams to train together for increasing team cohesiveness at work, a critical factor to patient safety1,13. To this purpose, the anesthesiology service of our hospital proposed the implementation of a multidisciplinary training activity aimed to improve knowledge and attitudes in NTS of the team members involved in the initial care of polytrauma patients.

CRM training using simulation strategies provides a more realistic environment than the traditional classroom1. In our program, the design of the different scenarios included exercises to work on specific aspects of CRM, including the exchange of roles17 and the introduction of distractors, which allowed to enhance situational awareness. The HFAS instrument was used to assess level 1 (reaction) of the Kirkpatrick’s four levels of training evaluation model23. In agreement with previous studies20, we found a positive improvement of attitudes in the leadership domain. Of note, the assignment of roles, the creation of mental models by the team leader and sharing them with the group, the importance of debriefing after the case and, very relevantly, accepting that assertive discussion about different therapeutic options between the leader and the team members empowers the team to solve cases more efficiently. These changes make the team feel integrated, so that each member knows clearly his/her functions and participates at all times in the evolution of the patient’s clinical condition, regardless of their professional category. Therefore, it is essential that leadership should be understood as a group property, which will empower the team in the patient’s care, to communicate critical situations, and to participate in decision-making and management of information (without followers, there can be no leaders).

In contrast to other studies20, we found an improvement in post-training scores in the questions related to “roles”, a finding that may be attributed to the exercises of the exchange of roles, which allowed to obtain a positive shift for a better knowledge of each member’s function within the team, the need to be familiar with other roles, and improvement of performance of the trauma team associated with training. All of these contributed to a better understanding of workloads and responsibilities of other team members, which can reduce pressure and stress increasing patient safety. There was also a significant improvement in all items related to “situational awareness” except for the opinion that individual performance is not adversely affected by the fact of working with less experienced personnel. In contrast to other studies20, the importance of being present in the briefing process was positively evaluated. The use of distractors in the simulation exercises probably contributed to alert participants on the need to ensuring performance and to be focused on the case before the patient’s arrival to avoid adverse events17,20.

In relation to the “communication” section, results obtained were similar to those reported in other studies20,24. There was a significant improvement in the need of training to speak up when team members seem something that is not going right and to speak aloud when a problem with the patient is perceived independently of who team member is. Improvements in other items, such as the number of persons in the trauma room, the noise level, or the quality of communication before arrival of the patient were not observed, probably because pre-training scores were already high as participants perceived communication as a relevant issue affecting the quality of care. On the other hand, responses to the ECC survey regarding the usefulness of CRM training were very favorable, with highest scores in those items related to safety and reduction of errors. Participants considered that training would be associated with an attitudinal change improving performance, an effect that was not reported in previous studies17.

The distribution of the professional profiles of participants was directly related to the actual trauma members in our hospital, with multidisciplinarity as of one of the key of success3. There are CRM training courses in which participants do not conform real teams, which diminishes credibility of simulation. In our program as well as in the study of Ziesmann et al.1, all participants were at the same level regardless of their professional category, training, or previous experience, so that performance of each team member was as much realistic as possible.

Finally, the number of participants in the CRM training courses was limited and the impact of positive reactions and attitudes on other levels of training evaluation, such as behavior and results were not analyzed.

A CRM training model developed for the initial care of polytrauma patients improved theoretical knowledge and participants perceptions and attitudes regarding leadership, communication, roles, and situational awareness of members of the trauma team.

FundingNone to be declared.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank Marta Pulido, MD, for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance.