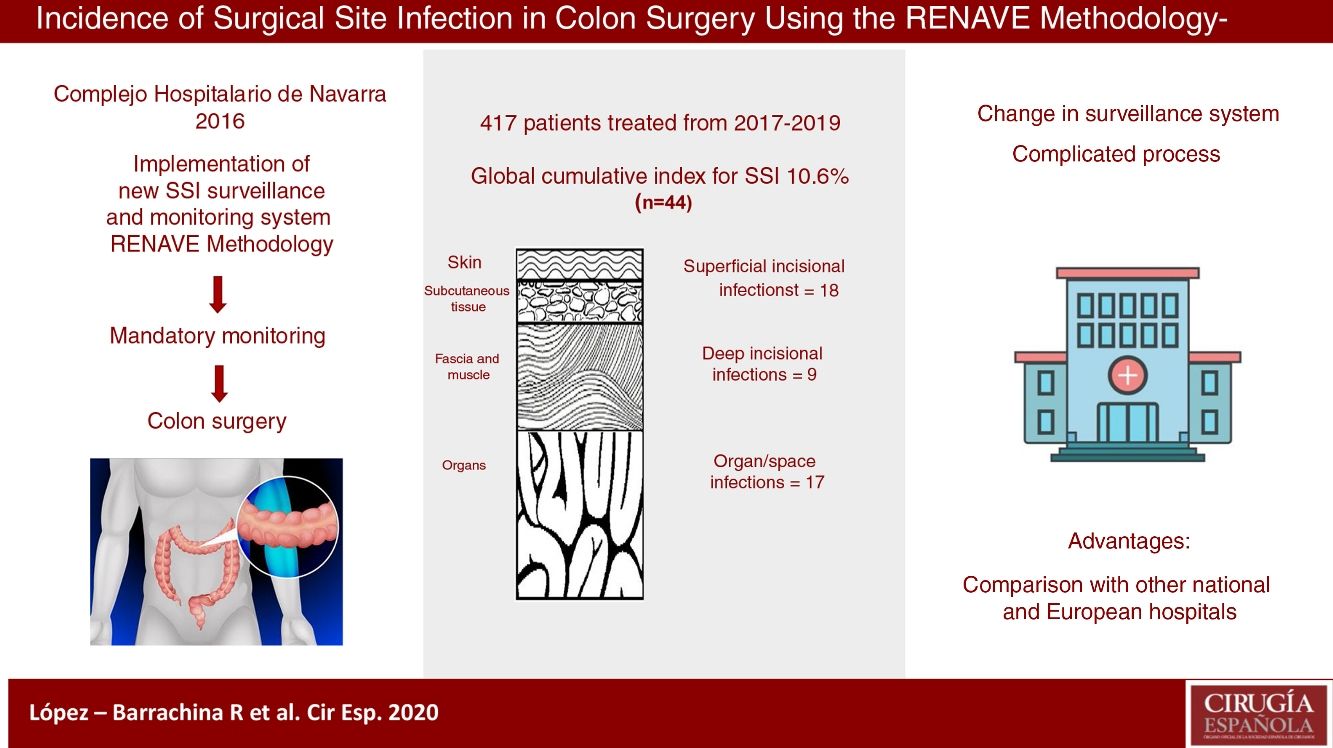

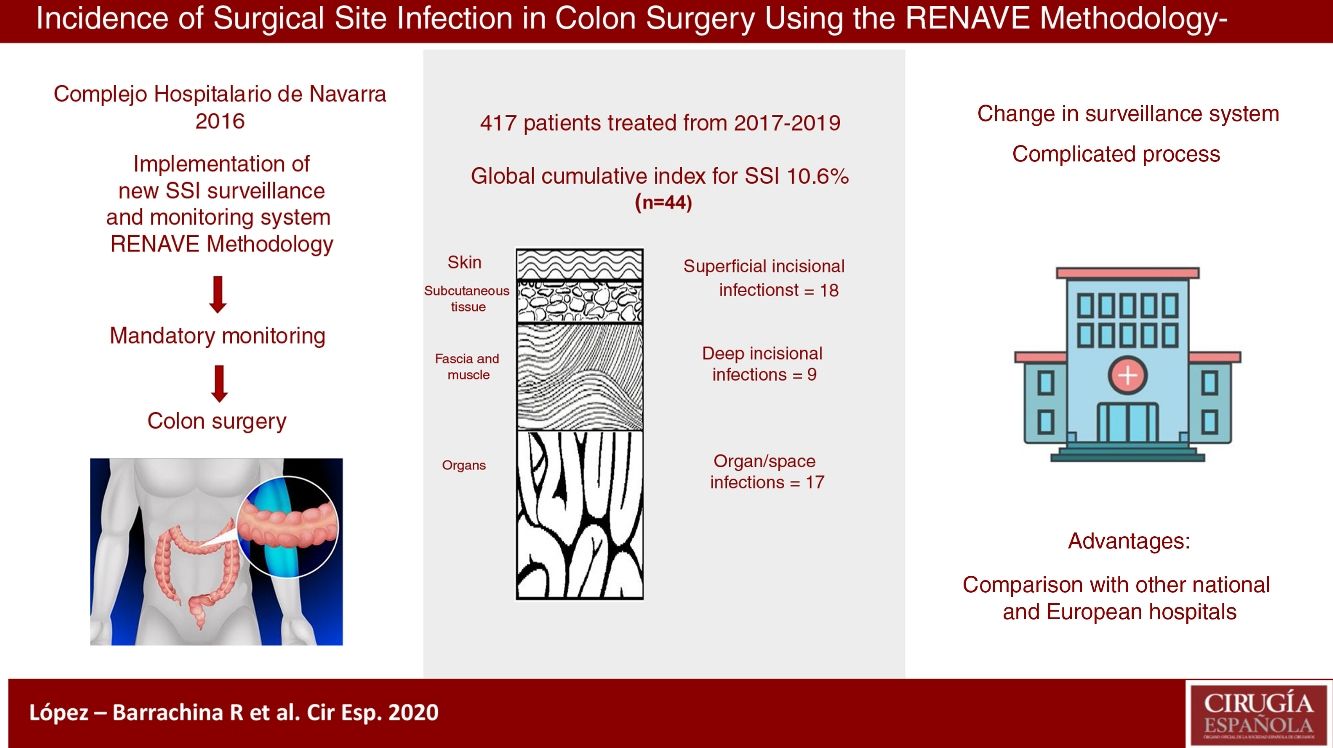

Navarra Hospital Complex has renovated its healthcare-associated infections surveillance and control methods meeting the requirements of the Spanish National Epidemiologic Surveillance Network. Surgical site infections are one of the most relevant adverse outcomes, being the colon surgery one of the mandatory monitored procedures. This system will ease, not only the yearly estimation of the hospital surgical infection rates, but also its comparison at national and European levels.

Methods416 patients underwent surgery between 2017 and 2019. Clinical variables were gathered during the patient hospitalization and up to 30 days from surgery, stratifying the cases by their NHSN (National Health Safety Network) surgical infection risk index. A univariant descriptive analysis was performed and outcome indicators were estimated.

ResultsThe cumulative incidence was 10.6%, with 44 cases. The rates were higher among the high-risk subgroups: 25.0% and 42.9%, respectively, for NSHN index categories 2 and 3.

ConclusionsThe incidence was similar to the ones found in other studies carried out in analogous conditions. However, the methodologic variability makes it difficult to compare results.

El Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra, centro sanitario de tercer nivel, implementó a partir de 2016 un nuevo sistema de vigilancia y control de infecciones relacionadas con la asistencia sanitaria según metodología de la Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica. Las infecciones del lugar quirúrgico constituyen uno de los efectos adversos más relevantes, siendo la cirugía de colon un procedimiento de vigilancia obligatoria. Este sistema permitirá al hospital conocer sus tasas de infección quirúrgica, contrastarlas periódicamente para vigilar su tendencia y compararlas con las de otras instituciones sanitarias nacionales y europeas.

MétodosCuatrocientos dieciséis pacientes intervenidos de colon durante 2017–2019 fueron estudiados prospectivamente durante su hospitalización y hasta los 30 días post-cirugía y estratificados según el riesgo de infección quirúrgica mediante el «índice NHSN» (National Health Safety Network). Se realizó un análisis estadístico descriptivo univariante y se calculó la incidencia acumulada de infección de lugar quirúrgico, global y por subgrupos según factores de riesgo.

ResultadosLa incidencia acumulada global de infección del lugar quirúrgico fue del 10,6% (n = 44), con mayor incidencia en subgrupos de alto riesgo quirúrgico: un 25,0% en la categoría 2 del índice NHSN y un 42,9% en la categoría 3.

ConclusionesLa incidencia acumulada de infección del lugar quirúrgico obtenida es similar a la calculada en otros estudios realizados en condiciones semejantes, pero existe una diversidad metodológica que hace compleja la interpretación.

The latest data of the European Center for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) from the study on the prevalence of Healthcare-Associated Infections (HAI) and use of antimicrobials (ECDC-PPS 2011–2012)1 conducted in 30 European countries (including Spain) reveal that 6% of patients admitted to hospital acquire at least one HAI. Out of the total of 15,000 registered cases, 19.6% were surgical site infections (SSI), which was the second most frequent after respiratory infections (23.5%). In the Spanish Nosocomial Infection study in Spain (Estudio de Prevalencia de las Infecciones Nosocomiales en España, EPINE)2 from 2018, SSI were the most frequent location, a circumstance that has been repeated continuously since 2015. SSI are one of the most relevant adverse effects associated with surgery because they increase morbidity, mortality, hospital stays and readmissions, the probability of receiving care in intensive units, the costs of health care, and patient suffering.3,4

Starting in 2016, the Complejo Hospitalario de Navarra (CHN) changed its traditional HAI surveillance model to a new system in line with the requirements of the Spanish National Epidemiological Surveillance Network (Red Nacional de Vigilancia Epidemiológica, RENAVE), which indicates colon surgery as a surgical procedure requiring surveillance.5 This model enables the CHN to periodically check its own infection rates and compare them with other national and European hospitals.

The objective of this study was to calculate the incidence, both global and stratified, according to risk subgroups, of SSI in colon surgery occurring during the 3 years after the implementation of the new surveillance system proposed by RENAVE at the CHN.

MethodsThe annual study of SSI incidence in colon surgery begins (prospective design) each year in January, and surgical interventions are selected until reaching the minimum sample indicated in the RENAVE Protocol of 100 surgical patients who were hospitalized for at least 48 h.

The collection of variables and the surveillance of the appearance of SSI cover the entire hospital stay of patients who have undergone colon surgery. In addition, a systematic post-discharge follow-up is carried out during the first 30 days after surgery, which analyze: emergency care episodes, readmissions to general surgery, scheduled visits in the outpatient clinic, and microbiological tests/cultures ordered. For the diagnosis of SSI, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC)6 criteria were used.

The preventive medicine service reviews the general surgery procedures from the previous day, considering the following inclusion criteria: elective colon surgery (understood as incision, resection or anastomosis of the large intestine, including the anastomosis from large-to-small or small-to-large intestine), a single procedure or associated with others (excluding rectal and urgent surgery), classified as clean-contaminated or contaminated and CIE-9-MC codes: 17.3 (laparoscopic partial excision of the large intestine), 45 (incision, bowel removal and anastomosis) and 46 (exteriorization of the large intestine).

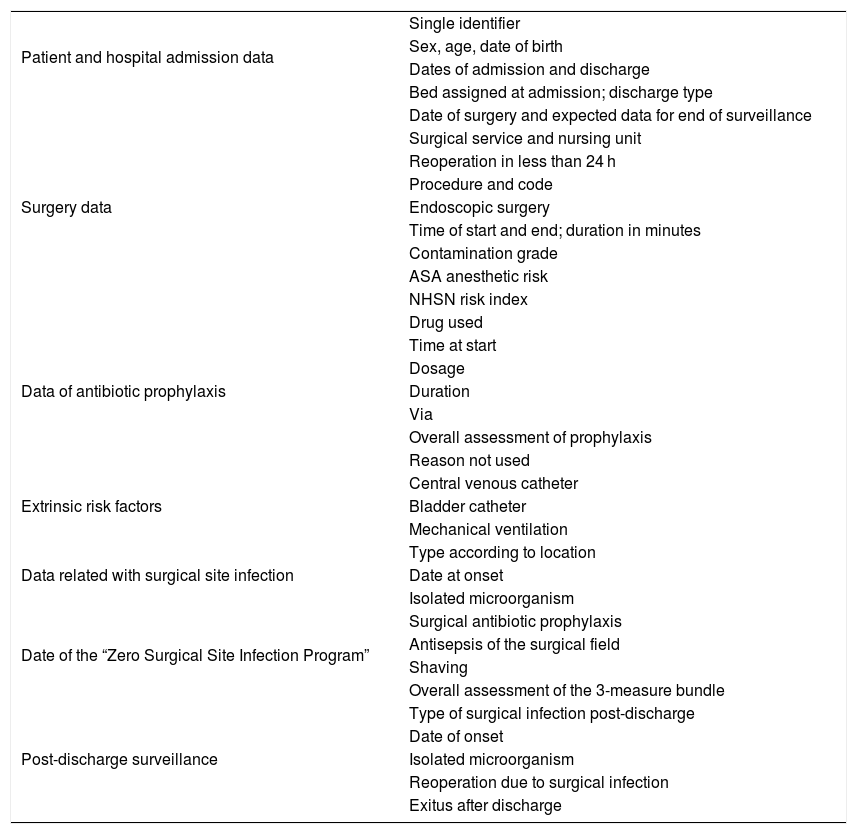

Once the intervention to be monitored has been identified, the patient’s clinical documentation is analyzed, extracting the variables of interest from the computerized patient history: sociodemographic data, risk factors, information related to hospitalization, surgery, and surgical site infection diagnosed at admission and during post-discharge surveillance (Table 1). If necessary, the care staff in charge of the patient is contacted directly. Subsequently, a paper form is completed for each operation. Once the post-discharge follow-up is completed, the information is entered into a Microsoft Access® database to be used and analyzed to prepare the ILQ report.

Variables analyzed for surgical site infection surveillance.

| Patient and hospital admission data | Single identifier |

| Sex, age, date of birth | |

| Dates of admission and discharge | |

| Bed assigned at admission; discharge type | |

| Surgery data | Date of surgery and expected data for end of surveillance |

| Surgical service and nursing unit | |

| Reoperation in less than 24 h | |

| Procedure and code | |

| Endoscopic surgery | |

| Time of start and end; duration in minutes | |

| Contamination grade | |

| ASA anesthetic risk | |

| NHSN risk index | |

| Data of antibiotic prophylaxis | Drug used |

| Time at start | |

| Dosage | |

| Duration | |

| Via | |

| Overall assessment of prophylaxis | |

| Reason not used | |

| Extrinsic risk factors | Central venous catheter |

| Bladder catheter | |

| Mechanical ventilation | |

| Data related with surgical site infection | Type according to location |

| Date at onset | |

| Isolated microorganism | |

| Date of the “Zero Surgical Site Infection Program” | Surgical antibiotic prophylaxis |

| Antisepsis of the surgical field | |

| Shaving | |

| Overall assessment of the 3-measure bundle | |

| Post-discharge surveillance | Type of surgical infection post-discharge |

| Date of onset | |

| Isolated microorganism | |

| Reoperation due to surgical infection | |

| Exitus after discharge |

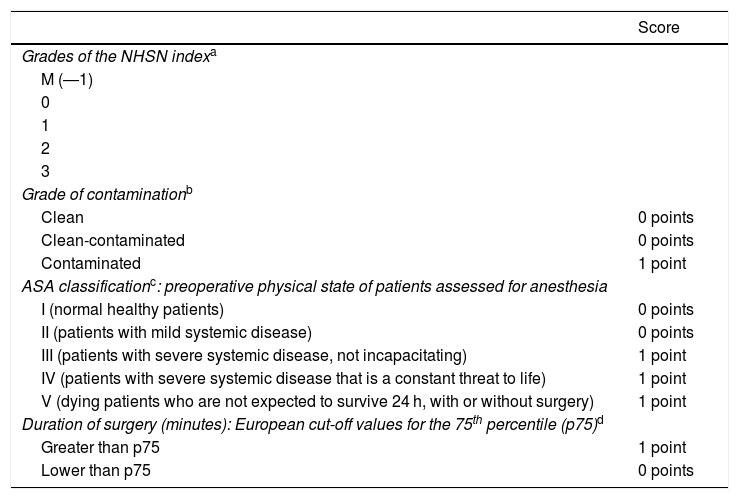

Surgical patients were stratified into five categories according to the risk of infection using the NHSN Index of the National Healthcare Safety Network to calculate the incidence and allow for comparisons between SSI figures. It assesses three main risk factors: degree of contamination from the surgery, preoperative physical state of the patient using the ASA (American Society of Anesthesiologists) score, and duration of the operation in minutes (Table 2).

Index of risk of the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN).

| Score | |

|---|---|

| Grades of the NHSN indexa | |

| M (―1) | |

| 0 | |

| 1 | |

| 2 | |

| 3 | |

| Grade of contaminationb | |

| Clean | 0 points |

| Clean-contaminated | 0 points |

| Contaminated | 1 point |

| ASA classificationc: preoperative physical state of patients assessed for anesthesia | |

| I (normal healthy patients) | 0 points |

| II (patients with mild systemic disease) | 0 points |

| III (patients with severe systemic disease, not incapacitating) | 1 point |

| IV (patients with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life) | 1 point |

| V (dying patients who are not expected to survive 24 h, with or without surgery) | 1 point |

| Duration of surgery (minutes): European cut-off values for the 75th percentile (p75)d | |

| Greater than p75 | 1 point |

| Lower than p75 | 0 points |

The statistical analysis of the patient characteristics and surgical procedure variables was descriptive and univariate. Qualitative variables were described with their frequency distribution (number and percentage), and quantitative variables were reported with their mean and standard deviation (SD). The cumulative incidence (CI) of SSI, both global and by subgroups, was calculated based on the NHSN index as outcome indicators. The CI was expressed as a percentage and a 95% confidence interval.

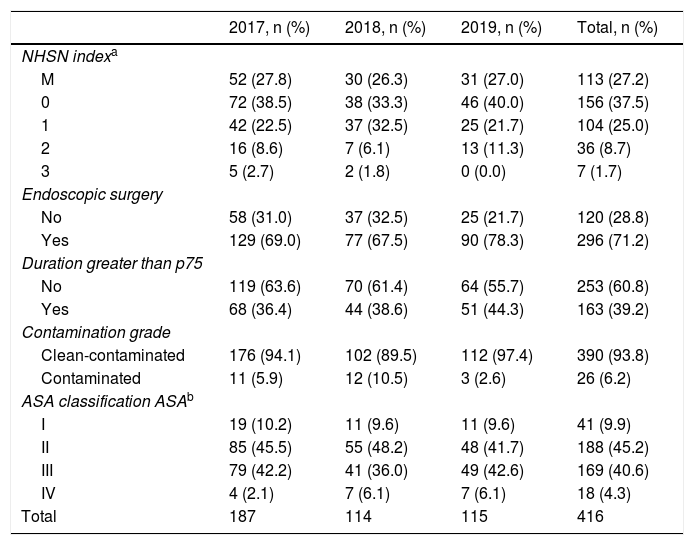

ResultsDuring the 3-year study, 416 patients with colon surgery were selected, 254 of which were men (61.1%). The mean sample age was 67.6 ± 11.8, with a range from 28 to 93. The mean hospital stay was 9.8 ± 7.6 days, and in 97.4% of the patients the reason for discharge was due to cure or improvement. There were 4 deaths: 3 in-hospital (0.7%) and 1 during follow-up (0.2%).

The most frequent surgical procedures, both laparoscopic, were right hemicolectomy and sigmoidectomy: 130 (31.3%) and 103 (24.8%), respectively.

The surgery was clean-contaminated in 390 (93.8%) interventions, with a mean duration of 174 min (62.8%) and performed laparoscopically in 296 (71.2%). Most of the patients were classified as ASA II-III: 357 (85.8%). Table 2 shows the distribution of cases according to the NHSN index.

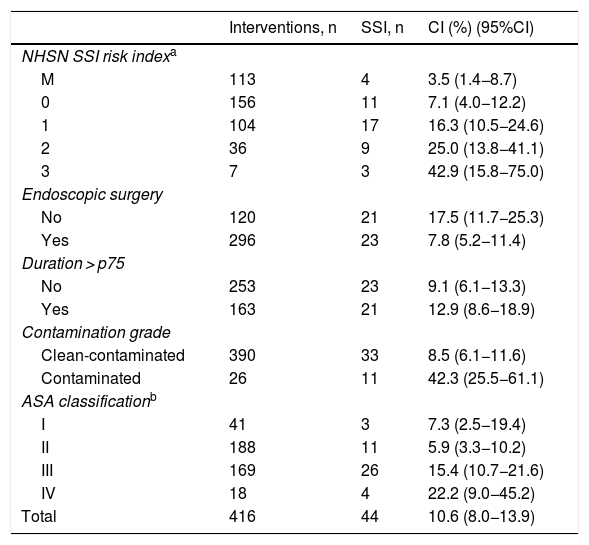

The cumulative incidence (CI) of SSI in colon surgery was 10.6% (10.2%, 12.3% and 9.6% individually for each year of study), with a total of 44 infections. The infections were classified as follows: 18 (40.9%) superficial incisional; 9 (20.5%) deep incisional; 17 (38.6%) organ/space; and 26 (60%) were diagnosed during the hospital stay. The type of infection most detected post-discharge according to depth was superficial incisional; specifically, there were 12 (66.7%).

CI presented a higher percentage in subgroups 2–3 of the NHSN index, in non-endoscopic surgery, contaminated type, ASA grades III–IV and those of duration greater than p75. Table 3 shows the CI according to risk factors (Table 4).

Main characteristics of cases included in the study.

| 2017, n (%) | 2018, n (%) | 2019, n (%) | Total, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHSN indexa | ||||

| M | 52 (27.8) | 30 (26.3) | 31 (27.0) | 113 (27.2) |

| 0 | 72 (38.5) | 38 (33.3) | 46 (40.0) | 156 (37.5) |

| 1 | 42 (22.5) | 37 (32.5) | 25 (21.7) | 104 (25.0) |

| 2 | 16 (8.6) | 7 (6.1) | 13 (11.3) | 36 (8.7) |

| 3 | 5 (2.7) | 2 (1.8) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (1.7) |

| Endoscopic surgery | ||||

| No | 58 (31.0) | 37 (32.5) | 25 (21.7) | 120 (28.8) |

| Yes | 129 (69.0) | 77 (67.5) | 90 (78.3) | 296 (71.2) |

| Duration greater than p75 | ||||

| No | 119 (63.6) | 70 (61.4) | 64 (55.7) | 253 (60.8) |

| Yes | 68 (36.4) | 44 (38.6) | 51 (44.3) | 163 (39.2) |

| Contamination grade | ||||

| Clean-contaminated | 176 (94.1) | 102 (89.5) | 112 (97.4) | 390 (93.8) |

| Contaminated | 11 (5.9) | 12 (10.5) | 3 (2.6) | 26 (6.2) |

| ASA classification ASAb | ||||

| I | 19 (10.2) | 11 (9.6) | 11 (9.6) | 41 (9.9) |

| II | 85 (45.5) | 55 (48.2) | 48 (41.7) | 188 (45.2) |

| III | 79 (42.2) | 41 (36.0) | 49 (42.6) | 169 (40.6) |

| IV | 4 (2.1) | 7 (6.1) | 7 (6.1) | 18 (4.3) |

| Total | 187 | 114 | 115 | 416 |

Accumulated incidence of surgical site infections in terms of risk factors.

| Interventions, n | SSI, n | CI (%) (95%CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| NHSN SSI risk indexa | |||

| M | 113 | 4 | 3.5 (1.4−8.7) |

| 0 | 156 | 11 | 7.1 (4.0−12.2) |

| 1 | 104 | 17 | 16.3 (10.5−24.6) |

| 2 | 36 | 9 | 25.0 (13.8−41.1) |

| 3 | 7 | 3 | 42.9 (15.8−75.0) |

| Endoscopic surgery | |||

| No | 120 | 21 | 17.5 (11.7−25.3) |

| Yes | 296 | 23 | 7.8 (5.2−11.4) |

| Duration > p75 | |||

| No | 253 | 23 | 9.1 (6.1−13.3) |

| Yes | 163 | 21 | 12.9 (8.6−18.9) |

| Contamination grade | |||

| Clean-contaminated | 390 | 33 | 8.5 (6.1−11.6) |

| Contaminated | 26 | 11 | 42.3 (25.5−61.1) |

| ASA classificationb | |||

| I | 41 | 3 | 7.3 (2.5−19.4) |

| II | 188 | 11 | 5.9 (3.3−10.2) |

| III | 169 | 26 | 15.4 (10.7−21.6) |

| IV | 18 | 4 | 22.2 (9.0−45.2) |

| Total | 416 | 44 | 10.6 (8.0−13.9) |

The microbiological diagnosis was positive in 28 (63.6%) of the SSI, although in 14 (31.8%) no cultures were performed. Overall, the flora found was of a mixed type (gram-positive and negative), with a predominance of enterobacteria.

DiscussionThe great disparity in the calculation of hospital infection indicators and the complexity of the epidemiology of SSI make it difficult to interpret the results obtained, as well as their comparison with other hospitals.

At the moment, RENAVE does not yet have available the SSI indicators of the hospitals that participate in the National HAI Surveillance System in order to compare them and with the countries that collaborate in the ECDC study. However, there are many articles published on surgical infection with diverse methodologies that we have analyzed to compare our results in colon surgery.

The 2017–2019 global CI of 10.6% is at the same level as the incidence obtained by other national researchers, such as Acín-Gándara et al.7 in 2007−2009. It is lower than that of Pérez et al.8 in 2008 (17.4%) or the Madrid-only study from 2009 (16.7%).9 However, these last two studies are different from ours because they included urgent surgery, which surely increased CI. Comparing the CHN rate with US studies, the situation is inverted, since the National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN)10 reported an incidence of 5.6% in the 2006–2008 period.

Regarding the European results of the Healthcare-Associated Infections Surveillance Network (HAI-Net)11 for the 2010–2011 biennium, the incidence of SSI in colorectal surgery was between 9.5% and 9.7%, while the rate in Spain was 20% (last year with available data). This report refers to certain factors that should be considered regarding the existing variability between different European countries, such as differing interpretations in the definition of SSI, especially in the superficial incisional type, whose incidence is underestimated by some surveillance systems. It should also be noted that SSI rates in colon surgery are not collected individually in all countries, but instead jointly with rectal surgery, which increases CI. Rectal operations are more complex and, therefore, involve longer surgical time, more bacterial contamination and ultimately an increased risk of adverse effects such as SSI.12

Recently, the Spanish Association of Coloproctology studied almost 2000 elective colon surgery patients from 18 units throughout the country from 2013 to 201713 and found a CI of 11.4%, which is very similar to ours. Even so, a study14 of 771 patients from 2008 to 2016 yielded figures practically equal to the aforementioned American results (5.8%).

At the last Conference on Patient Safety in the Surgical Block held by the Ministry of Health in 2019, an incidence rate in colon surgery of 12.1% was reported15 by the 55 national hospitals that are currently adhering to the Zero Surgical Infection Project.

The surveillance system of the INCLIMECC16 (Clinical Indicators for Continuous Quality Improvement) network, which includes 64 hospitals from 12 autonomous communities in Spain, published in 2019 the SSI indicators obtained by the participating hospitals for 11 years (2007–2017). For 27 843 colon surgeries, the overall incidence rate was 16.9%. This system follows standards recommended by UNE norms and by RENAVE and only monitors the SSI during the hospital stay or re-admission after discharge, which inevitably leads to underdiagnosis. Our follow-up is more exhaustive because we included emergency services, outpatient consultations and primary care for 30 days after surgery, in addition to microbiological testing requests. And, despite being a more comprehensive surveillance, our CI is lower.

By infection type, superficial incisional SSI was 40.9%, which is almost as frequent as organ/space type at 38.6%. Deep incisional infections accounted for 20.5%, with great interannual variability. In other studies, the organ/space SSI was lower than the incisional (superficial-deep), such as the Ho et al.17 results with 9.9% compared to 12.9%, a surprising circumstance considering that the monitored procedures were colorectal, which usually entail more infections than exclusively colon operations. In an evaluation carried out in 140 English hospitals with 6 528 colon surgeries,18 40.6% of SSI were organ/space, which was twice the number reported by HAI-Net,11 at 20%.

The literature review showed great diversity in the published incidence figures. This may be due to the methodology used or differences in study design, patient profiles, or even in the SSI definitions used.19 CI rates may also vary depending on the hospital type: higher in small health centers, perhaps due to insufficient experience in these surgical procedures, as well as not having more specialized surgical units available.12 There are studies that calculate the incidence when patients are discharged from the hospital, without monitoring the entire risk period.20 This prevents exact comparisons to be made, because some monitor SSI for 30 days after surgery, and others only during hospitalization.21 Limón and Shaw22 reported that 22.5% of SSI were detected after discharge, a percentage that is even higher in other studies, such as a study conducted from 2000 to 2005 in a Spanish hospital with 260 beds23 with 44.5%, or the Marchi et al.24 study from Italy with 51%. These data are very interesting because postoperative hospital stays have significantly decreased in recent years, which greatly increases the possibility of diagnosing SSI after patient discharge.

The CDC25 recommends the use of post-discharge surveillance and recognizes its evaluation both with direct examination of the wound in consultations (by reviewing medical records), or with mail-in or telephone surveys of patients asking whether they think they have had an infection. Authors like Whitby et al.26 do not consider the patient’s opinion to be very objective and believe that it should not be given value. In the CHN, in accordance with RENAVE, monitoring was done for 30 days after the procedure, so as not to underestimate the incidence of SSI, extending surveillance to all public health facilities where the patient may have had the surgical wound treated.

Incidence density is considered one of the frequency measures that best adjusts to the reality of SSI, because it partially avoids the observation bias caused by differences in length of hospital stay and follow-up.21 Our research has not calculated this, which leads to some difficulty in interpreting the rates.

We feel that another of the drawbacks of this study is that we have not analyzed the influence of the etiology of the underlying pathology on the appearance of SSI. Colon cancer surgery is associated with the highest risk of complicated infection, and the incidence can triple compared to other surgical interventions.12 In this study, the caseload has brought together neoplastic etiology and others, such as inflammatory bowel disease.

The specific case mix of each sample could also partially justify the variation observed in the rates. The ASA grade in most of our patients does not seem to differ from others, as is the case in the series by Cima et al.,27 in which more than 95% of the colorectal interventions had a grade of II, III or IV. Furthermore, the percentage of patients with a NHSN index of risk for surgical infection ≥1 was 35.3%, which is somewhat lower than reports by other authors, such as Pujol et al.,28 who quantified it at 45%.

CHN colon surgeries were laparoscopic in almost three-quarters of patients (71%) and have seen an increase of more than 10% in the last year. In the series by Martín et al.29 from 2009 to 2011 in a Basque hospital, it was clear that at the beginning of the study only 25% of colorectal interventions were laparoscopic, a figure that reached 60.5% in just 2 years. Similar research shows the growing importance of laparoscopy as a technique in colon surgery.30

To conclude, and in agreement with other studies in our setting, it should be noted that, despite having obtained an CI for SSI of 10.6%, the great methodological variability makes data comparison difficult and increases the complexity of its interpretation. Therefore, initiatives that arise that promote progress in this direction, such as the RENAVE proposal, should be recognized.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: López Barrachina R, de la Cruz Tabares E, Guzmán Collado IT. Incidencia de infección de localización quirúrgica en cirugía de colon según metodología RENAVE: estudio prospectivo 2017–2019. Cir Esp. 2021;99:34–40.