The hepatic cystic tumour is a very rare neoplasm, representing about 5% of all cystic liver neoplasms. The preoperative diagnosis is difficult and can lead to confusion. The aim of this study is to analyze a number of cases operated at our centre with an histologic diagnosis of liver cystic neoplasms and also to describe the sintomathology, diagnosis and management as per the recent classification.

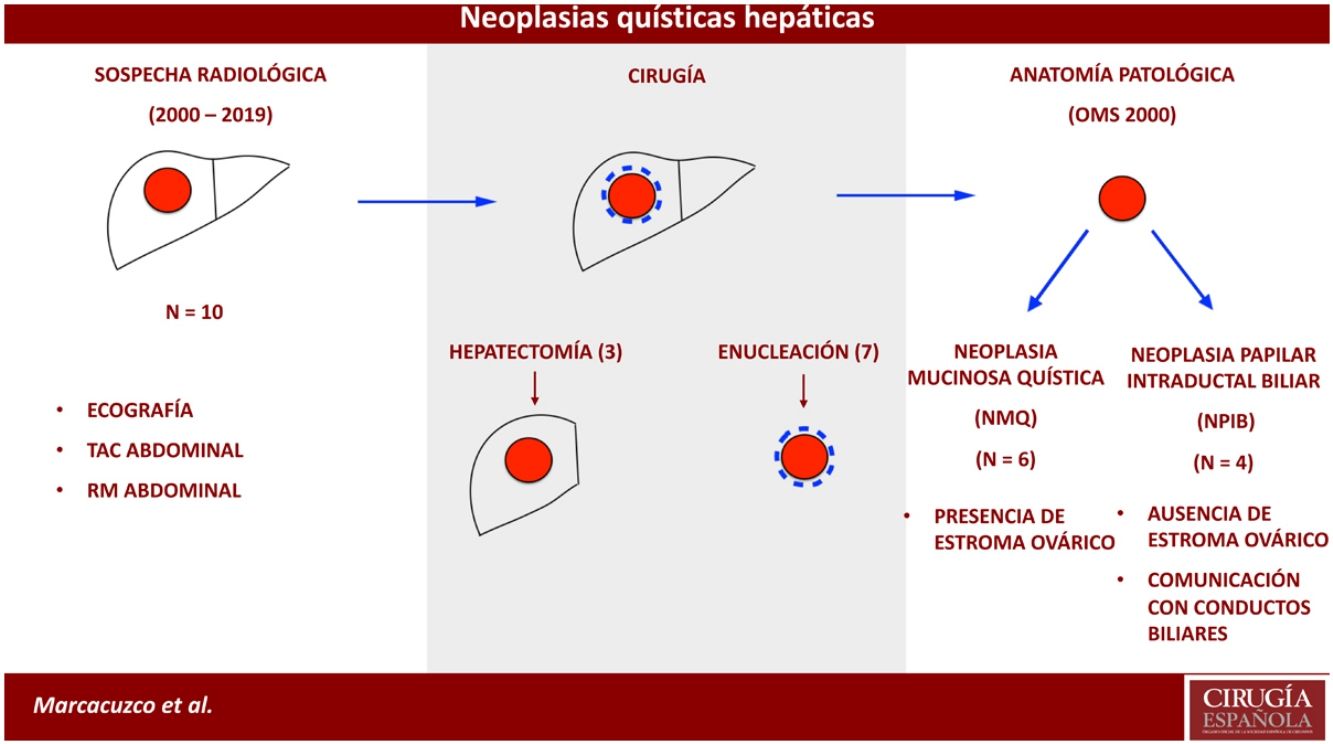

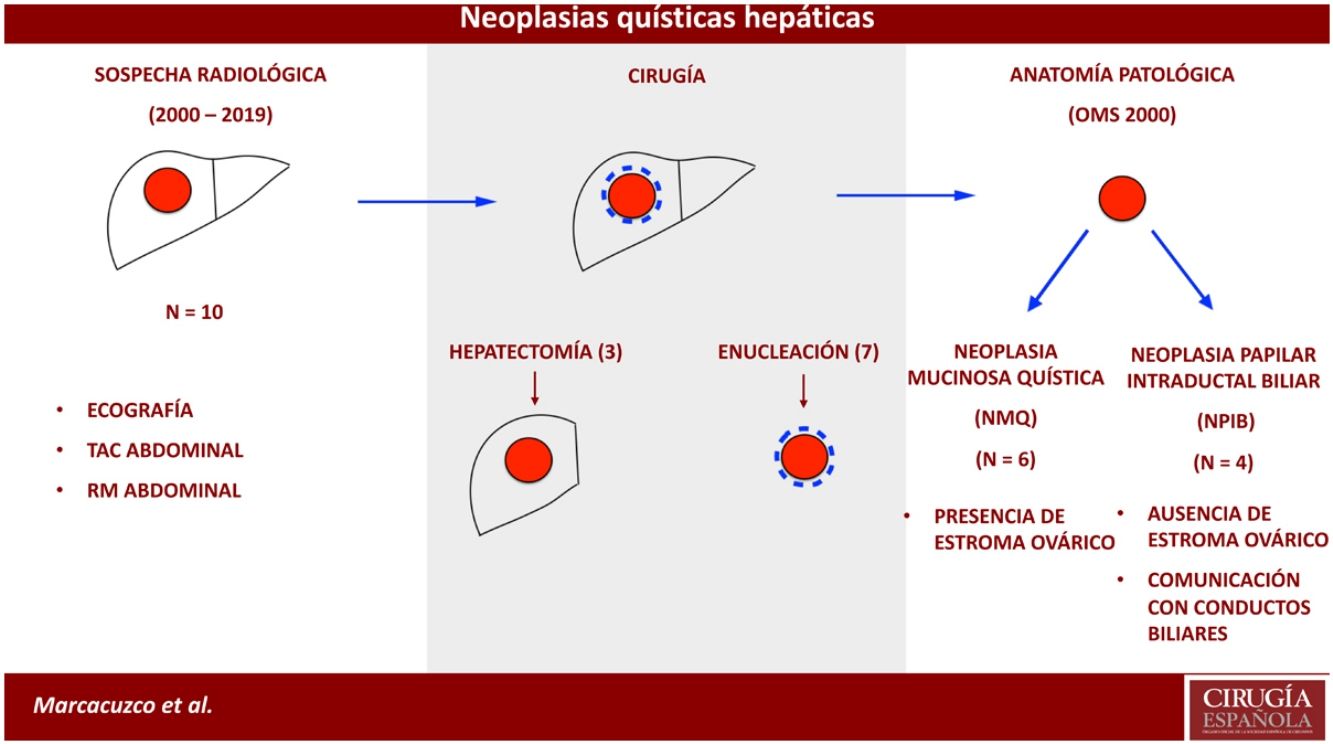

MethodsA retrospective analysis was performed including all the cystic liver neoplasms operated between January 2000 and December 2019. The study was performed based on the pre-existing pathology archives. The 2010 previous cases were reclassified following the new 2010 OMS classification.

ResultsThe study sample was of 10 patients, identifying 6 of them as mucinous cystic liver neoplasms, and the other 4 as intraductal papillary biliary neoplasms. The majority of the patients were women (8/10) and the median age was 47 years. Regarding the treatment, 3 hepatectomy and 7 enucleations were performed. Frozen section intraoperatively was not required in any case. In one case, variable cellular atypia with areas of adenocarcinoma was observed, and the patient received neoadyuvant chemotherapy with taxol and carboplatin. In all cases the resection margins were negative.

ConclusionCystic liver neoplasms are infrequent tumours with a difficult differential diagnosis. Therefore, with a high radiological suspicious, the treatment should be a complete resection to avoid recurrences and malignancies.

La neoplasia quística hepática es una neoplasia poco frecuente, que representa aproximadamente el 5% de las lesiones quísticas del hígado. El diagnóstico preoperatorio es difícil y puede causar confusión. El objetivo del estudio es analizar una serie de casos operados en nuestro centro con diagnóstico anatomopatológico de neoplasia quística hepática y describir la sintomatología, diagnóstico y tratamiento de acuerdo con la actual clasificación.

MétodosSe realizó un análisis retrospectivo de todas las neoplasias quísticas hepáticas operadas entre enero de 2000 y diciembre de 2019. El estudio se basó en los informes de anatomía patológica ya existentes. Los casos anteriores al 2010 fueron reclasificados según la clasificación de la OMS del año 2010.

ResultadosLa muestra total del estudio resultó en 10 pacientes: 6 fueron neoplasias mucinosas quísticas hepáticas y 4 neoplasias papilares intraductales biliares. La mayoría de los pacientes fueron mujeres (8/10) y la edad media fue de 47 años. En cuanto al tratamiento, hubo 3 hepatectomías y 7 enucleaciones. En ningún caso se realizó una biopsia intraoperatoria de los márgenes quirúrgicos. En un caso se observó atipia celular variable con zonas de adenocarcinoma, por lo que el paciente recibió quimioterapia adyuvante con taxol y carboplatino. En todos los casos los márgenes de resección fueron negativos.

ConclusiónLas neoplasias quísticas hepáticas son tumores poco frecuentes, que plantean un dilema en el diagnóstico diferencial, por lo que, ante la sospecha radiológica, el tratamiento de elección debería ser la resección completa del tumor para evitar su malignización y la recidiva.

Mucin-producing cystic tumours of the liver with biliary epithelium were traditionally called cystadenomas or mucinous cystadenocarcinomas, depending on their degree of aggressiveness.1,2 In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed a new classification: intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct (IPNB) and mucinous cystic neoplasm (MCN).3

These tumours represent 5% of non-parasitic liver cysts. They usually occur in middle-aged women and are typically asymptomatic. IPNB and MCN are cystic formations, with a multilocular appearance and mucinous content in most cases. In addition, they tend to grow slowly, while lymph node involvement and the appearance of metastases are rare.4,5

In recent years, their incidence has grown due to incidental findings during radiological tests for other causes. However, despite advances in imaging techniques, their diagnosis and management continue to be a challenge in daily clinical practice.

The objectives of this study are to analyse a series of cases treated surgically at our hospital with a pathological diagnosis of cystic neoplasm of the liver, and to describe the symptoms, diagnoses and treatment following the current classification.

MethodsWe conducted a retrospective analysis of all cystic neoplasms of the liver treated surgically at our hospital between January 2000 and December 2019. The study complied with the recommendations of the hospital Ethics Committee for handling personal data.

The study was based on existing pathology reports. Cases prior to 2010 were reclassified in accordance with the 4th Edition of the WHO Classification of Tumours of the Digestive System (2010), which classifies these tumours as MCN and IPNB.3 For the purpose of this study, all cases were reviewed by the same pathologist.

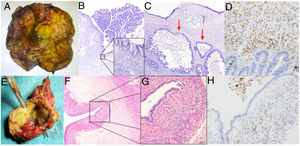

MCN is a cyst formation in the liver or in the bile duct that is lined by cuboidal or columnar epithelium, with variable mucin production and associated with ovarian stroma, which is not always easily recognizable. The presence of ovarian stroma was confirmed by immunohistochemistry through the characterization of oestrogen or progesterone receptors. MCN can be classified as having low, moderate or high-grade dysplasia, and even be associated with invasive carcinoma.

In contrast, IPNB are premalignant lesions that present villous or papillary growth of the intraductal epithelium. The columnar epithelium can progress from low to high-grade dysplasia and even invasive carcinoma. The differentiation of the epithelium can be intestinal, biliary, oncocytic or gastric; half of cases contain at least 2 types of epithelium, so they are classified by the predominant type. In addition, pancreatobiliary IPNB is more frequently associated with invasive carcinoma, with a more aggressive pattern and more frequent metastasis.6 These neoplasms do not show signs of differentiation towards ovarian stroma, and mucin production is variable.7 The diagnosis of IPNB was reached by observing papillary proliferations in the absence of ovarian stroma, in addition to the presence of communication between the cyst and the bile ducts.

We also registered data for demographics, symptoms, liver function tests, tumour markers and imaging studies.

The indication for surgery was established by the presence of a cystic lesion that did not meet the radiological criteria for benign cyst, parasitic cyst, or liver abscess. The aim of surgical treatment in all cases was complete resection of the lesion, and either hepatectomy or enucleation was proposed depending on the size, location or suspicion of malignancy. The cases in which malignancy was confirmed were assessed jointly with the medical oncology department.

ResultsFrom 2000 to 2010, 4 cases with pathological diagnosis of cystadenoma or mucinous cystadenocarcinoma were identified and subsequently reclassified according to the 2010 WHO classification. In addition, another 6 cases of MCN or IPNB were observed after 2010. Therefore, the total study sample included 10 cases: 6 MCN (one with infiltrating carcinoma), and 4 IPNB. Most of the patients were women (8/10), and the mean age was 47.

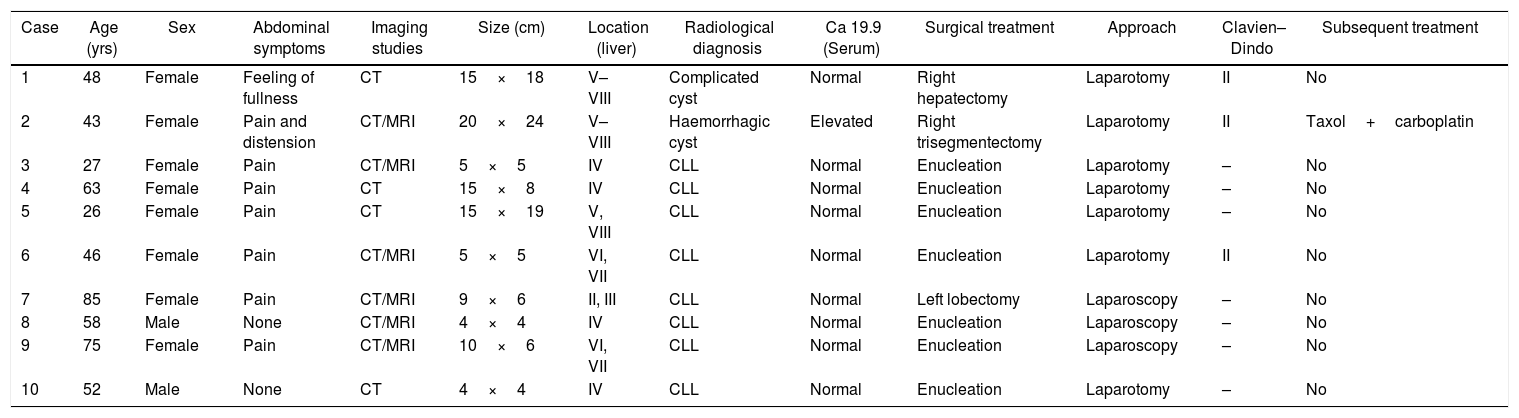

Abdominal pain was the most frequent symptom (6 patients). One patient presented a ruptured cyst with hemoperitoneum that required deferred urgent surgery. In no case did we observe signs of obstructive jaundice or symptoms derived from compression of the tumour on the main structures (Table 1).

Clinical, radiological and treatment characteristics in patients with cystic neoplasms of the liver.

| Case | Age (yrs) | Sex | Abdominal symptoms | Imaging studies | Size (cm) | Location (liver) | Radiological diagnosis | Ca 19.9 (Serum) | Surgical treatment | Approach | Clavien–Dindo | Subsequent treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | Female | Feeling of fullness | CT | 15×18 | V–VIII | Complicated cyst | Normal | Right hepatectomy | Laparotomy | II | No |

| 2 | 43 | Female | Pain and distension | CT/MRI | 20×24 | V–VIII | Haemorrhagic cyst | Elevated | Right trisegmentectomy | Laparotomy | II | Taxol+carboplatin |

| 3 | 27 | Female | Pain | CT/MRI | 5×5 | IV | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparotomy | – | No |

| 4 | 63 | Female | Pain | CT | 15×8 | IV | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparotomy | – | No |

| 5 | 26 | Female | Pain | CT | 15×19 | V, VIII | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparotomy | – | No |

| 6 | 46 | Female | Pain | CT/MRI | 5×5 | VI, VII | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparotomy | II | No |

| 7 | 85 | Female | Pain | CT/MRI | 9×6 | II, III | CLL | Normal | Left lobectomy | Laparoscopy | – | No |

| 8 | 58 | Male | None | CT/MRI | 4×4 | IV | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparoscopy | – | No |

| 9 | 75 | Female | Pain | CT/MRI | 10×6 | VI, VII | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparoscopy | – | No |

| 10 | 52 | Male | None | CT | 4×4 | IV | CLL | Normal | Enucleation | Laparotomy | – | No |

CLL: cystic lesion of the liver; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; CT: computed tomography.

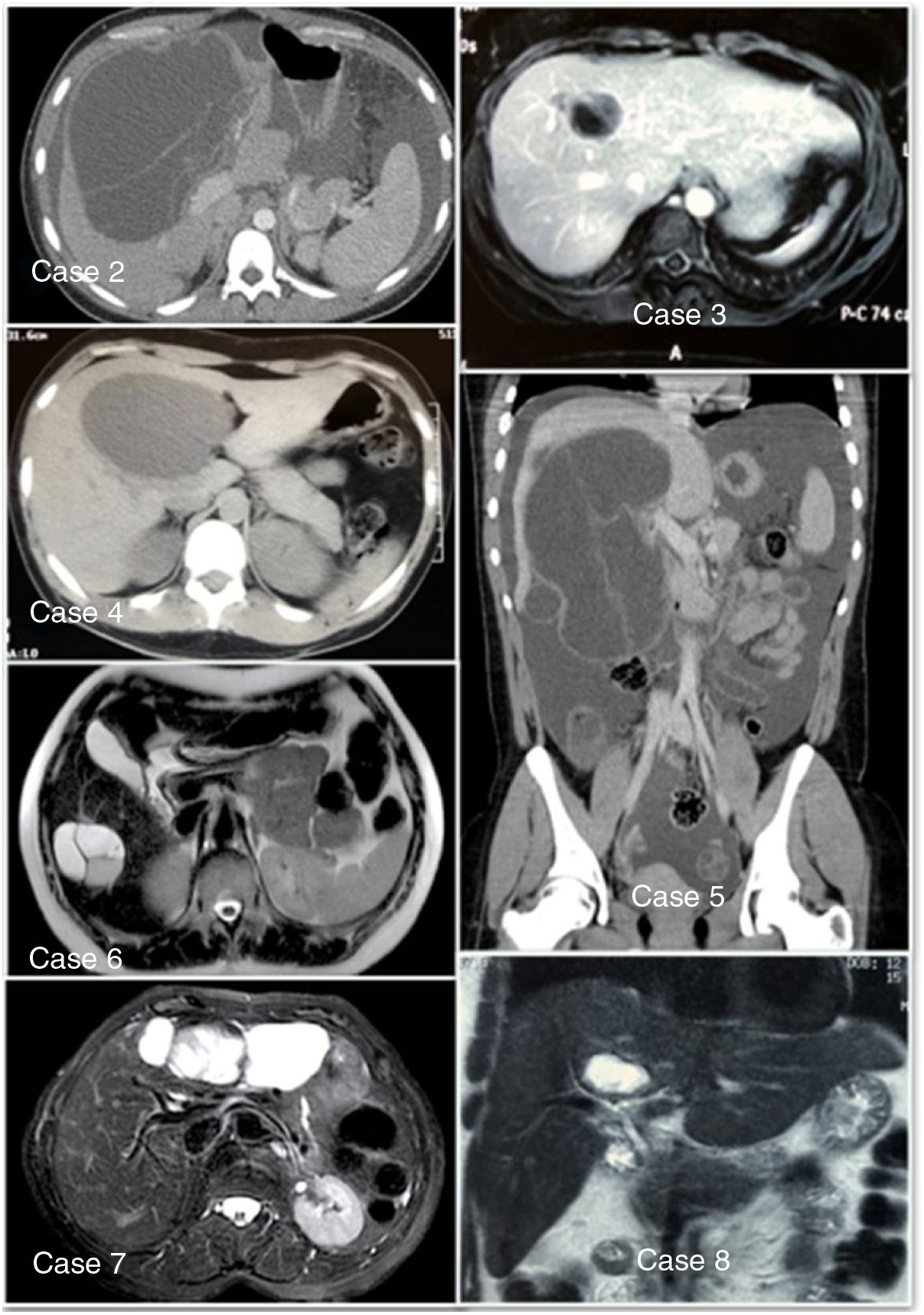

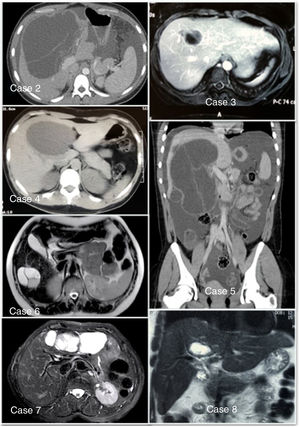

The diagnostic approach started with ultrasound, and the study was completed with an abdominal CT scan in all cases (Fig. 1). In 6 patients, magnetic resonance imaging was used to better visualize the lesion, demonstrating multilocular cysts with vascularized internal septa. In our series, the mass was located in the right hepatic lobe in 5 patients. In no case was PET/CT or endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography used as part of the preoperative study, nor was fine-needle aspiration done of the cyst in order to analyse tumour markers.

Liver function tests and hydatid serology were normal in all patients. In addition, only one patient presented elevated tumour markers.

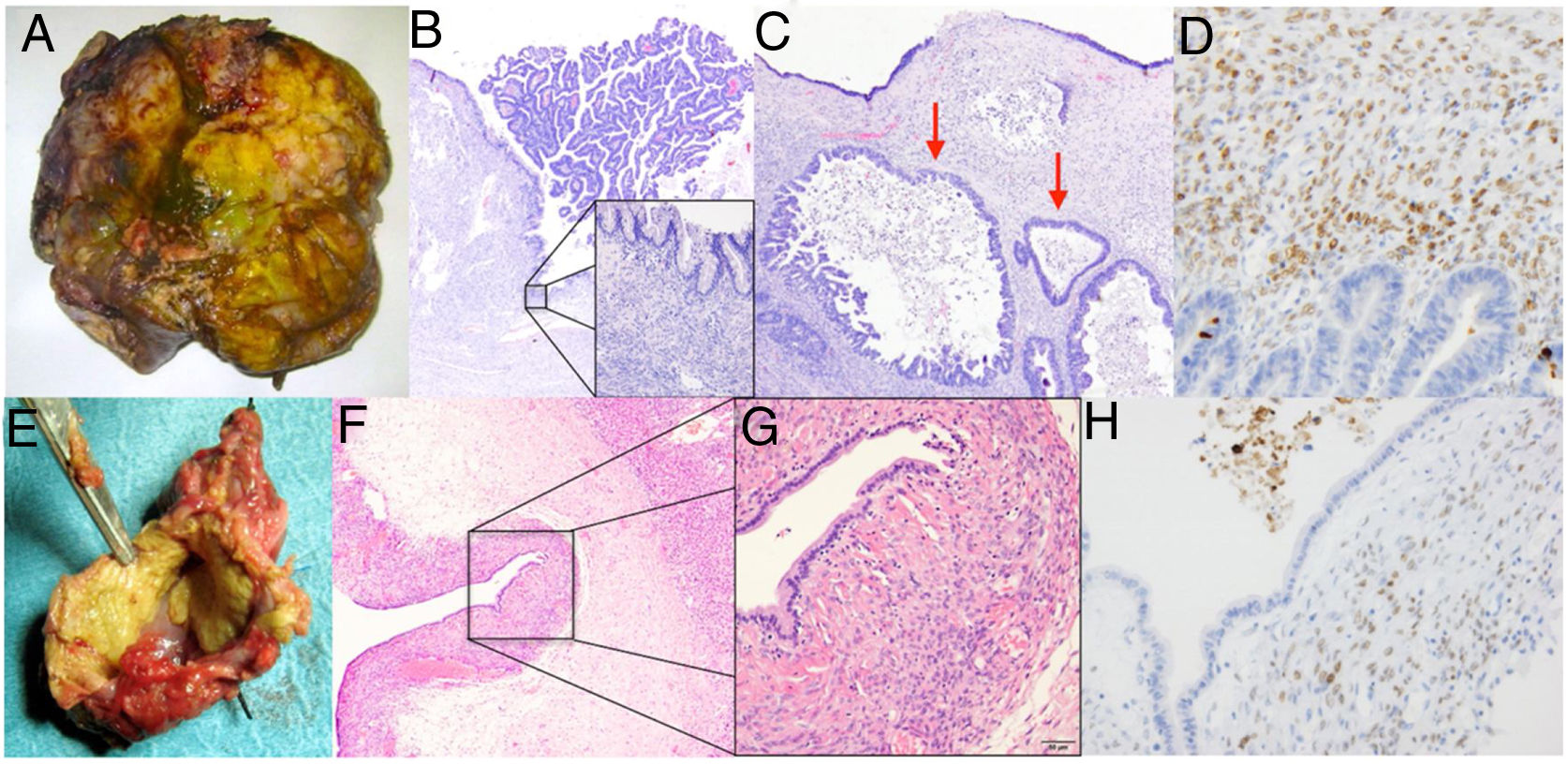

In terms of surgical treatment, 3 hepatectomies were performed (one right, one right trisegmentectomy, and one left lobectomy due to the size of the lesions) and 7 enucleations were done (Fig. 2). In no case was an intraoperative biopsy of the surgical margins performed.

Case 2: (A) hepatectomy specimen including the cystic lesion; (B) this lesion presents a mucinous epithelial lining and areas of intraluminal proliferation (40×, haematoxylin–eosin); (C) presence of areas with high-grade surface dysplasia and invasive carcinoma (arrows) (200×, haematoxylin–eosin); (D) positive immunohistochemistry for Müllerian stroma markers.Case 3: (E) macroscopic image of an atypical liver resection specimen; (F) the histological study shows the presence of a cyst lined with simple epithelium (40×, haematoxylin–eosin); (G) under the epithelium, a dense underlying cellular stroma characteristic of mucinous cystic neoplasms is observed (400×, haematoxylin–eosin) is observed; (H) immunohistochemical staining image showing stromal cells with nuclei positive for anti-progesterone and oestrogen receptor antibodies with positive nuclear staining.

Postoperative evolution was favourable in all patients, although a type II complication (Clavien–Dindo) was observed in 3 patients.

The pathology report confirmed the presence of cystic liver lesion, all of which were mucinous, with the presence of biliary epithelium. Ovarian stroma positive for oestrogen receptors was observed in 6 cases. The remaining 4 showed no evidence of stroma, although there was presence of communication with the adjacent biliary branches and papillary growth in the neoplastic epithelium. In one case, cellular atypia was observed with dysplasia and areas of infiltrating adenocarcinoma, and in all cases the resection margins were negative (Table 2).

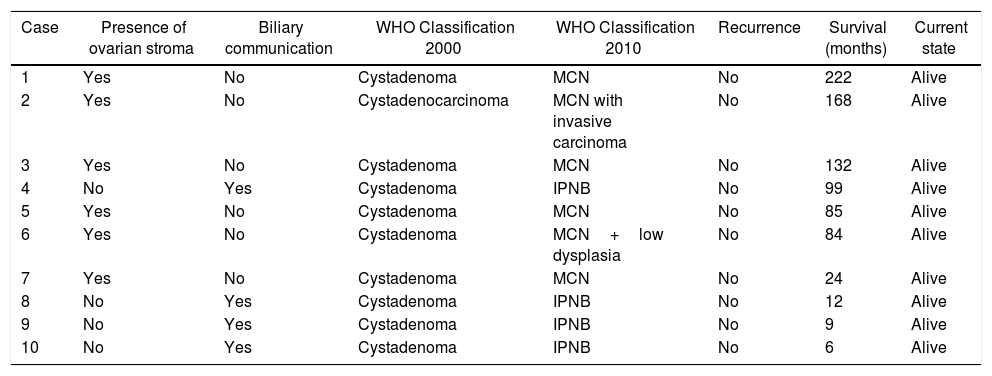

Classification of intrahepatic cystic lesions according to histology.

| Case | Presence of ovarian stroma | Biliary communication | WHO Classification 2000 | WHO Classification 2010 | Recurrence | Survival (months) | Current state |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yes | No | Cystadenoma | MCN | No | 222 | Alive |

| 2 | Yes | No | Cystadenocarcinoma | MCN with invasive carcinoma | No | 168 | Alive |

| 3 | Yes | No | Cystadenoma | MCN | No | 132 | Alive |

| 4 | No | Yes | Cystadenoma | IPNB | No | 99 | Alive |

| 5 | Yes | No | Cystadenoma | MCN | No | 85 | Alive |

| 6 | Yes | No | Cystadenoma | MCN+low dysplasia | No | 84 | Alive |

| 7 | Yes | No | Cystadenoma | MCN | No | 24 | Alive |

| 8 | No | Yes | Cystadenoma | IPNB | No | 12 | Alive |

| 9 | No | Yes | Cystadenoma | IPNB | No | 9 | Alive |

| 10 | No | Yes | Cystadenoma | IPNB | No | 6 | Alive |

MCN: mucinous cystic neoplasm; IPNB: intraductal papillary neoplasm of the bile duct.

Median follow-up was 60 months, with an ultrasound or abdominal CT scan 6 and 12 months after surgery. In no case was recurrence of the tumour observed on the imaging tests. The follow-up of the patient with presence of an infiltrating carcinoma included annual CT scan for 5 years. In addition, this patient received adjuvant chemotherapy with Taxol and carboplatin.

DiscussionCystic neoplasms of the liver can be asymptomatic and an incidental finding, especially in small lesions. On other occasions, they can cause symptoms such as abdominal pain, palpable mass, a feeling of fullness and, rarely, jaundice or symptoms related to the location of the tumor.8

Radiological diagnosis is difficult and can often lead to a misdiagnosis, as it can be confused with a liver abscess, haemorrhagic cyst, simple cyst, hydatid cyst, or Caroli's disease.9 Improvements in imaging techniques have resulted in an increase in the detection of this tumour, but they are not sufficient for a definitive diagnosis.10 The radiological pattern of a cystic lesion of the liver can be that of a mass with dilatation of the proximal or distal bile duct, or that of a unilocular or multilocular cyst with solid areas in the lumen. In our series, 8 patients were diagnosed with cystic neoplasm of the liver by imaging studies.

Patients with these neoplasms usually have liver function tests within normal levels, although there are cases with elevated transaminases, bilirubin, gamma-glutamyl transferase, and alkaline phosphatase; this was not the case in our series. Nevertheless, these laboratory abnormalities do not make it possible to differentiate between a cystic liver lesion and a simple cyst.11

The analysis of Ca 19.9 and CEA in serum and cystic fluid is controversial. Its sensitivity and specificity are not high enough12 and do not allow us to distinguish between a benign or malignant tumour. The levels can be elevated in either a low-grade MCN or an IPNB with carcinoma in situ. However, elevated tumour markers during patient follow-up could be an indicator of malignant transformation or recurrence in cases of incomplete resections.13 In our series, elevated serum Ca 19.9 was observed in only one patient, the pathological analysis was of an MCN with invasive carcinoma, and in no case was Ca 19.9 analysed in the cystic fluid.

On the other hand, FNA of the cyst is not very specific and has occasionally been associated with pleural and peritoneal dissemination, so it is not recommended.14 Thus, in our series, it was not used in any case.

However, there are certain risk factors that can make us suspect malignant behaviour of a cystic neoplasm of the liver, such as: age, being male, having symptoms that have evolved over a short time, tumour size and presentation in the right liver.15 Furthermore, radiologically, the presence of wall nodules with thickened and irregular walls may favour malignancy of a cystic liver lesion.16

In 2000, the WHO gave the names cystadenomas or mucinous cystadenocarcinoma to any cystic lesion lined with epithelium located in the liver or biliary tract.17 Later, in 2010, the WHO classified these tumours as MCN (with the presence of ovarian stroma in the immunohistochemical analysis), and IPNB (the absence of ovarian stroma and communication of the tumour with the bile duct are essential in this type of tumour).3 In addition, each of these entities can be associated with different degrees of dysplasia, and even invasive adenocarcinoma.

Quigley et al.18 reviewed cystic lesions of the liver in search of ovarian stroma and reclassified them according to the 2010 WHO definition, obtaining 36 patients with MCN. However, 25% of the patients previously diagnosed with cystadenomas or cystadenocarcinoma did not present ovarian stroma and could not be classified as MCN. Furthermore, the tumours were mainly located in the left liver, a circumstance that could be explained by the theory of the embryological development of the gonads on the same axis as the left liver and the pancreas. In our series, in 5 cases the location of the neoplasms was in the left liver, and 2 of them were MCN.

Zen et al.19 described a series of 29 cases of MCN and 12 of IPNB over a period of 20 years. In this multicentre study, the differences between both tumours were noticeable from the radiological, microscopic and immunohistochemical standpoint, such that the MCN were larger tumours, with the presence of septate multilocular cysts or the appearance of a cyst within another cyst and a higher prevalence of multiple cysts; in the case of IPNB, including the presence of intramural papillary nodules.

Budzynska et al.20 mentioned the presence of ovarian stroma and communication with the bile duct in the same hepatic cystic tumour, which suggests that in exceptional cases MCN can break the bile duct or that there may be cases of overlap: thus, the 2010 WHO classification is somewhat rigid.

On the other hand, Albores Saavedra et al.21 described tumours that contained ovarian stroma but whose epithelium was non-mucinous; they also lacked dysplastic epithelium and, therefore, were not associated with invasive carcinoma. It is important to bear in mind that the rate of malignant transformation of this type of tumour can be up to 20%. The description of the non-mucinous epithelium is of particular importance, considering that the malignant potential of MCN increases after the epithelium presents mucinous differentiation. Therefore, the presence of a non-mucinous biliary epithelium could be the initial phase in the development of the lesion, and the following step would be the appearance of a mucinous epithelium.22 In addition, mucin production by liver tumour cells has been associated with biliary differentiation.

Nakanuma et al.23 proposed dividing IPNB into 2 types: type 1, or the classic intraductal papillary mucinous tumour similar to that of the mucin-producing pancreas, with gastric or intestinal differentiation epithelia; and type 2, which always presents epithelium with high-grade dysplasia, characterized by intestinal or pancreatobiliary differentiation, with more irregular areas in the papillae and a complex, cribriform or invasive pattern.

The treatment of choice should be complete surgical resection of the lesion with negative margins to avoid recurrences. Thus, surgical resection can be either anatomical or non-anatomical, according to the location of the tumour and its relationship with main vascular structures. In our series, the resections were both anatomical and enucleated, depending on the liver segments involved and the involvement of the main biliary or vascular structures. Enucleation is recommended in central tumours with bilateral extension or in livers with previous parenchymal damage.24 As for the surgical approach, the use of laparoscopy is increasingly accepted, as a higher recurrence rate has not been demonstrated with its use. The intraoperative biopsy of the dissection margin is controversial, as it is not usually representative.25

Other treatments, such as percutaneous aspiration, sclerosis, ethanol injection, marsupialization, or unroofing, are considered inappropriate due to the malignant potential and high recurrence rate. Therefore, given the suspicion of a cystic liver lesion and the difficulty in differentiating between benign and malignant cases in the preoperative study, the treatment of choice should be complete tumour resection.26,27

In exceptional cases, liver transplantation may be indicated. Romagnoli et al.28 described the case of a 53-year-old female patient with a centrally located tumour compatible with MCN and a history of obstructive jaundice. Due to the technical impossibility of surgical resection with free margins, liver transplantation was proposed and carried out without incident. However, liver transplantation in this type of tumours raises several issues, such as the need for lifelong immunosuppression and the possibility of tumour recurrence, which is still not known due to the limited number of publications because transplantation has only been carried out in anecdotal cases. In the specific case of MCN, the presence of ovarian stroma reinforces the low malignant potential of these lesions, comparable with the recurrence rate of hepatocellular carcinoma, hepatic adenomatosis or hemangiomatosis. Therefore, the indication for liver transplantation in these patients should not be the norm, but it could be an alternative in symptomatic patients with large masses, in whom liver resection could pose an excessive risk.

In conclusion, cystic neoplasms of the liver are rare tumours that pose a dilemma in the differential diagnosis. Therefore, in the event of radiological suspicion, the treatment of choice should be complete resection of the tumour to avoid its malignization and recurrence.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Marcacuzco Quinto AA, Anisa Nutu O, Rodríguez Gil Y, Manrique A, Calvo Pulido J, García-Sesma Perez-Fuentes Á, et al. Neoplasias quísticas hepáticas: experiencia en un único centro y revisión de la literatura. Cir Esp. 2021;99:27–33.