Minimally invasive approaches for endocrine surgery of the neck are the result of efforts by several surgeons to extrapolate to neck surgery the proven benefits of minimally invasive techniques from other regions of the body, including less pain, morbidity and hospital stay. However, the main argument that led to the introduction of these techniques was the improvement of esthetic results. Endoscopic and robotic remote-access endocrine neck approaches through small incisions have been developed over the last 25 years and are constantly being refined. The objective of this review is to determine the current state of the literature through a systematic evaluation of the different techniques available in minimally invasive endocrine surgery of the neck, either with or without remote access, by describing their main characteristics and evaluating their advantages, disadvantages and controversies, while discussing their role and future in neck surgery.

Los abordajes quirúrgicos mínimamente invasivos en cirugía endocrina cervical son el resultado del esfuerzo de varios cirujanos para extrapolar los beneficios comprobados de técnicas mínimamente invasivas en otras regiones del cuerpo, como la reducción del dolor, la morbilidad y el tiempo de hospitalización. Sin embargo, el principal argumento que condujo a la introducción de estas técnicas fue la mejora de los resultados estéticos. Los abordajes endoscópicos y robóticos a través de pequeñas incisiones se han desarrollado durante los últimos 25 años y continúan en un constante refinamiento. El objetivo de esta revisión es describir el estado actual de la literatura, a través de una evaluación sistemática, de las diferentes técnicas disponibles dentro de la cirugía endocrina cervical mínimamente invasiva ya sea con acceso cervical o remoto, describiendo sus características principales y evaluando sus ventajas, desventajas y controversias, para discutir finalmente su papel en la cirugía actual y el futuro que tienen estos procedimientos.

Conventional surgery of the endocrine glands located in the neck is generally done with a classic Kocher incision, which typically leaves a considerably large, visible scar on the neck.1 Minimally invasive techniques used in other parts of the body reduce pain, morbidity and hospitalization time when compared to traditional techniques. These benefits are the initial arguments to extrapolate minimally invasive surgery techniques to cervical endocrine surgery, but the clear improvement in esthetic results is the main argument leading to the introduction of specialized techniques for thyroidectomy and parathyroidectomy.2 Visible cervical scars have a demonstrated negative psychological impact, regardless of the type of scar or its extension. In certain cultures (Asian, for example), such scars can cause social stigma.3–6

Since 1996, when Gagner first described minimally invasive endoscopic parathyroidectomy with cervical access, several remote-access approaches have been developed to avoid neck scarring.7 These endoscopic and robotic approaches through small cervical, axillary, anterior pectoral, breast, retroauricular or transoral incisions have been developed over the last 25 years and continue to be constantly refined.8–52 It should be clarified that, although the origin of these techniques is based on minimally invasive surgery used in other parts of the body, it is controversial to call remote-access approaches ‘minimally invasive’ surgery. By definition, minimally invasive surgery aims to perform the same procedure as open surgery while minimizing tissue damage. In approaches with remote access, however, greater tissue dissection is necessary due to the location of the incisions in non-visible places. Notwithstanding, these techniques are considered minimally invasive because of the small incisions used.

However, despite the attractive esthetic benefit of these techniques, the variety of approaches from around the world for minimally invasive endocrine surgery (MIES) in the neck have been contemplated with caution, as their implementation presents controversies due to technical challenges, new associated risks, their oncological equivalence and cost problems.1 The advantages that have been observed compared to the conventional approach justify the publication of a systematic review focused on these innovative techniques. The objective of this review is to describe the current state of the different MIES techniques available based on a systematic evaluation of the literature, analyzing the advantages, disadvantages, controversies and the future role of these approaches.

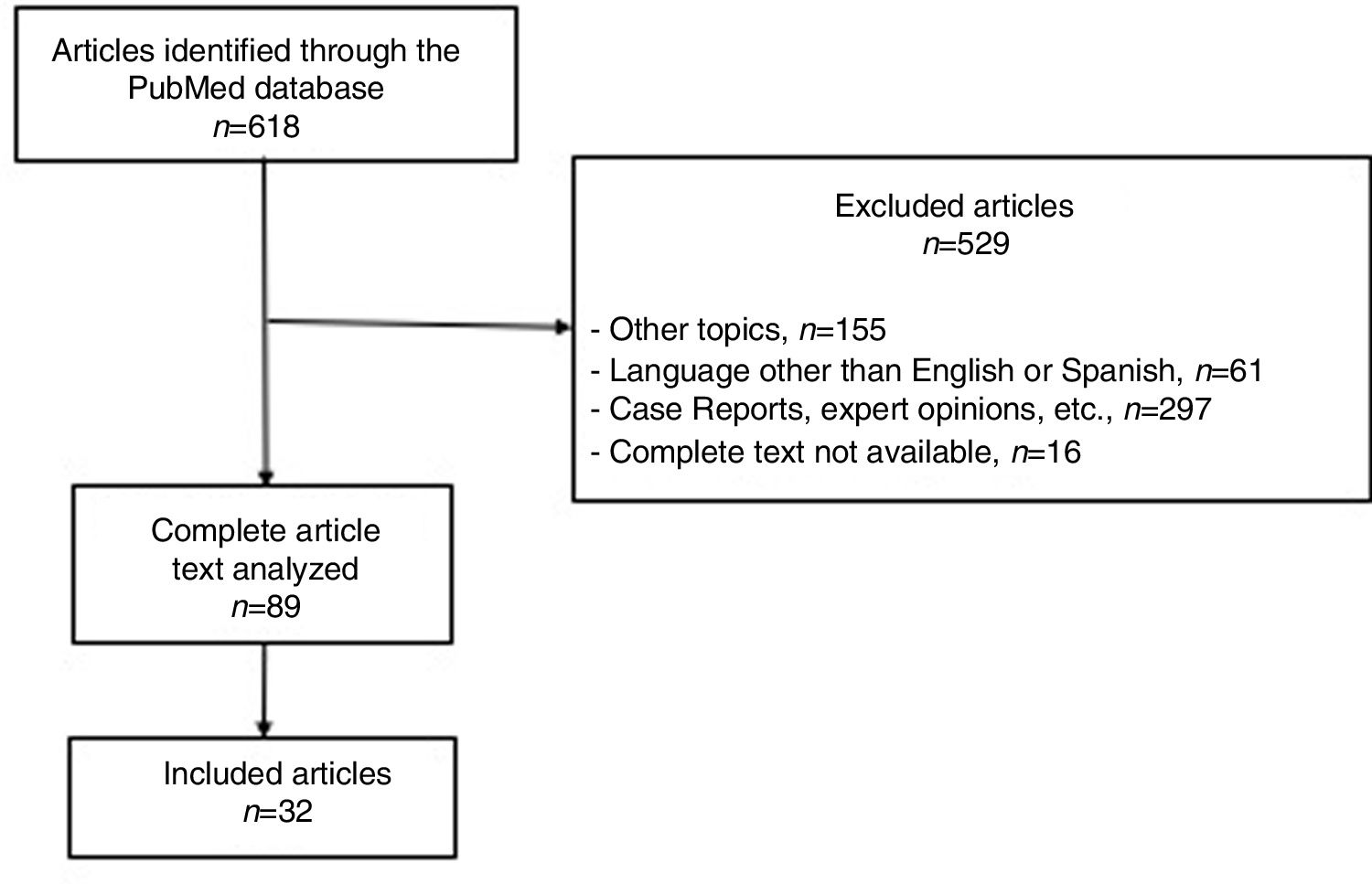

MethodsSearch StrategyA systematic review of the literature was performed in accordance with the PRISMA protocol.53,54 The relevant literature was selected from a search of the PubMed database up to November 2018, with the following keywords: “thyroidectomy, parathyroidectomy, endocrine surgery, neck surgery, minimally invasive endocrine neck surgery”, “remote access endocrine neck surgery”, “robotic endocrine neck surgery”, “endoscopic endocrine neck surgery”, “robotic thyroidectomy”, “robotic parathyroidectomy”, “endoscopic thyroidectomy”, “endoscopic parathyroidectomy”, “minimally invasive thyroidectomy”, “minimally invasive parathyroidectomy”, “remote access thyroidectomy”, “remote access parathyroidectomy”, “video-assisted endocrine surgery”, “video-assisted parathyroidectomy”, “video-assisted thyroidectomy”, “transoral thyroidectomy” and “transoral parathyroidectomy”.

Selection CriteriaThe inclusion criteria were: (1) studies on minimally invasive cervical and endocrine surgery; (2) articles written in English or Spanish; and (3) studies in adult patients. A manual review was carried out to exclude: (1) animal or cadaveric studies; (2) cadaver case reports; (3) images or videos; (4) expert opinions; and (5) comments or correspondence.

ResultsA total of 618 articles were identified in the systematic search with the keywords listed above. Out of the total number of articles identified, 529 were excluded because they did not meet the selection criteria. The full texts of the remaining 89 were evaluated and 32 were part of our qualitative analysis, becoming the basis of this review (Fig. 1).

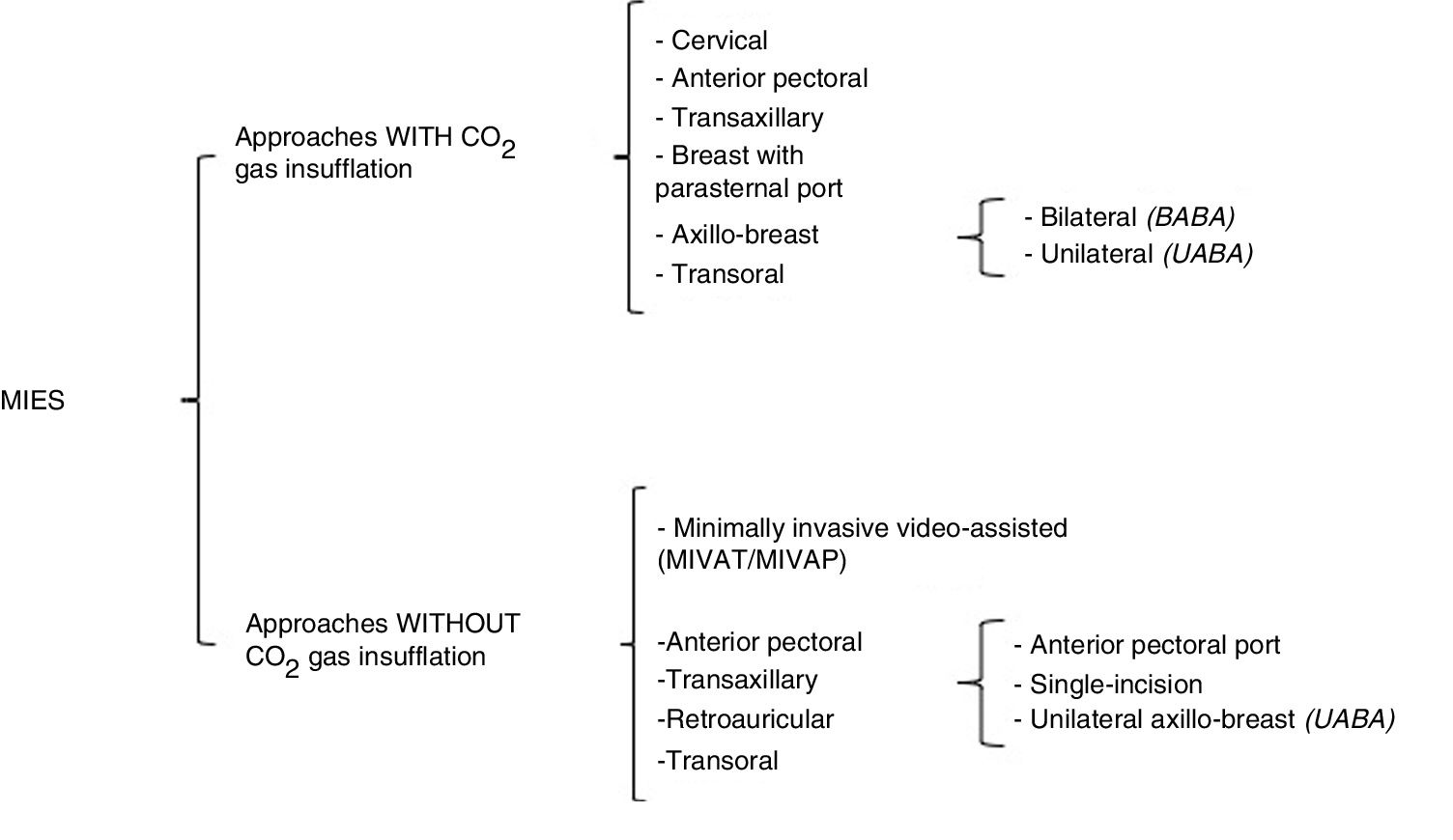

Definition and ClassificationsIn 1996, Gagner described the first endoscopic parathyroidectomy. Subsequently, Hüscher et al. reported the first endoscopic thyroidectomy in 1997, using the cervical approach with insufflation of carbon dioxide (CO2).7,8 In 1999, Miccoli et al. introduced minimally invasive video-assisted thyroidectomy without gas insufflation to avoid complications associated with CO2, such as extensive tissue dissection, postoperative subcutaneous emphysema, etc.9,47 From there on, multiple approaches were developed for remote-access cervical endocrine surgery, with the fundamental objective of preserving the esthetics of the neck. In this review, MIES will be defined as surgery of the endocrine glands located at the cervical level (thyroid and parathyroid) that can be carried out with small incisions, either cervically or using remote access (axillary, anterior pectoral, breast, retroauricular or transoral). MIES mainly uses special surgical instruments that in turn can be either endoscopic or robotic.27 This type of approach can also be classified according to the use or not of CO2 insufflation or the site of the incision(s) (Fig. 2). The approaches that use CO2 insufflation are cervical, transaxillary, breast (with or without a parasternal port), anterior pectoral, transoral, and bilateral or unilateral axillo-breast approaches. Gasless approaches include minimally invasive video-assisted techniques (thyroidectomy/parathyroidectomy) (MIVAT/MIVAP), anterior pectoral, transaxillary (with anterior pectoral port, single incision or unilateral axillo-breast), retroauricular and transoral, including different modifications and combinations of these approaches.8–52

In the cervical approach, 3 or 4 ports are used: one 12-mm for the optics, and 2 or 3 ports for operative instruments (usually 5mm), placed on the anterior or lateral side of the neck.8,20,29,36,46 The work space is maintained with the insufflation of CO2 at low pressure (5–10mmHg). MIVAT/MIVAP procedures are direct-access cervical methods, using a central incision measuring 1.5–2cm in length and without CO2 insufflation, which generates a smaller cervical scar than with the conventional approach. Some authors have demonstrated that this fact has a favorable impact on esthetics and postoperative pain when compared with the classic technique; however, even though this scar is smaller, it is still visible.9,31,37,40

Anterior Pectoral ApproachThe anterior pectoral or anterior thoracic approach, with CO2 insufflation, involves 3 ports in the anterior thoracic wall, placed just above the pectoralis major muscle.55 The gasless variation has also been described, in which 3 ports are used in the anterior thoracic wall; however, either an elevation device in the cervical region or an external retractor is necessary.48–50

Transaxillary ApproachIn 2000, Ikeda et al. described the transaxillary approach with gas insufflation and 3 axillary incisions, which is currently one of the endoscopic techniques used around the world.42,56 The gasless transaxillary approach described by Yoon et al. in 2006 evolved from one 6-cm incision (where the skin retractor, optics and an operative instrument are inserted) with one small anterior port at the sternum to the use of a single axillary incision without the anterior thoracic port.10,51,52 However, for a greater angle of movement between the instruments and to avoid collisions, current transaxillary approaches are now using a periareolar 5mm port, as in the unilateral axillo-breast approach (UABA) described by Tae et al.11,33

Breast and Axillo-breast ApproachesThe breast approach with gas insufflation uses 2 breast ports (bilateral periareolar) and a parasternal port.15,16 Due to esthetic issues, several modifications were developed to avoid the parasternal port, adding one or two axillary ports.17,18 It is necessary to make a distinction between the bilateral axillo-breast approaches: (1) the approach described by Shimazu et al. in 2003,17 which uses 2 periareolar incisions and one axillary port (axillo-bilateral-breast approach, or ABBA); and (2) the technique described by Youn et al. in 2007 (bilateral axillo-breast approach, or BABA), which is a modification of the ABBA with an additional axillary port (one incision in each areola and one incision in each axilla).19,38,57,58

Retroauricular ApproachThe retroauricular approach was developed by Terris et al. using a surgical robot,59 but it was popularized by the Koh, Jung and Tae group in Korea.21,27 The ports for the retroauricular approach include retroauricular and occipital incisions, similar to those used in parotidectomies, excision of submandibular glands and cervical tumors.49,60 The theoretical advantages of this approach are the need for a smaller dissection area, since the distance is shorter from the site of the incision to the cervical gland compared to other types of remote access. In addition, there is increased preservation of esthetics, since the scar is hidden behind the ear and covered by the hair.34,61,62 The disadvantages of these procedures are the narrow work space and the difficulty to dissect the contralateral thyroid lobe through a unilateral incision, and a contralateral retroauricular incision is sometimes necessary.23,34,62

Transoral ApproachThe transoral approach is the most recent description of a minimally invasive approach with remote access. In 2011, Wilhelm and Metzig were the first to perform a transoral thyroidectomy in humans, using a sublingual port and 2 oral vestibular ports.63 The transoral endoscopic approach with 3 vestibular incisions has recently been evaluated by Anuwong et al. in 60 thyroidectomized patients using this technique, considering it feasible and safe.64,65 The theoretical advantages described are less dissection in terms of work space than other remote-access types (such as transaxillary or retroauricular), facilitation of bilateral approaches necessary in total thyroidectomy or bilateral parathyroidectomies (because access is provided from the midline to the entire thyroid gland and the 4 parathyroid glands), and facilitation of the central dissection of the neck, theoretically being able to reach up to level VII, since a craniocaudal view of the cervical structures is provided.27,28,30,45,66

In perspective, the unilateral axillo-breast approach (UABA) with or without gas, the bilateral BABA, the retroauricular and the transoral approaches are the remote-access (non-cervical) techniques that have been more widely implemented at referral hospitals that conduct MIES. However, there have been several recent publications about the retroauricular and transoral approaches compared to other remote access approaches.8–52

Current Implementation of Remote-access Minimally Invasive Endocrine Surgery (MIES) in the NeckDifferences Between PopulationsMost of the studies that evaluate these approaches come from Asian countries, particularly from South Korea. However, the acceptance and implementation of these approaches has been slower in Europe and the United States. This is partly due to the differences in the patient population, the practice patterns and the interest of each patient, but it is also due to the controversies that these approaches present. In one of the largest studies reported to date, Ban et al., in a study of 3000 patients treated with transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy by Dr. Chung's team, reported a mean age of 39 years, with a mean body mass index (BMI) of 22kg/m2 and small thyroid nodules (mean 0.66cm).67 In a study with 1026 patients operated on with a robotic platform, Lee et al. reported patient characteristics similar to the series described above.68 The largest series of robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy in the United States highlights the differences in the demographic characteristics of patients treated surgically in this country, including patients with a mean BMI of 28.5kg/m2 and an average nodule size of 2.4cm.69 In Europe, one of the largest series with 257 patients who had undergone robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy, which was recently published, shows patient characteristics similar to those reported by the Asian series, but we must point out the strict patient selection criteria for this study.70

AdvantagesEach of the 4 most used procedures in remote-access MIES (UABA, BABA, retroauricular and transoral) have their own advantages and disadvantages, so it is therefore difficult to conclude which is the best approach. In general, methods with CO2 insufflation have the advantage of exposing and maintaining the workspace after a small remote-access skin incision is made at a site beyond the neck. Therefore, postoperative esthetics may be better than with gasless methods requiring long skin incisions, even if they are in a remote area around the neck. However, insufflation of CO2 can cause associated complications, such as subcutaneous emphysema, hypercapnia, respiratory acidosis, cerebral edema and even CO2 embolism, although the risk is low if pressure levels between 4 and 6mmHg are used.71 Gasless methods have the relative advantages of maintaining a clear view of the surgical field and no complications related to CO2 insufflation. The BABA and the transoral approach facilitate the performance of total thyroidectomy and bilateral parathyroidectomies, since they provide access to all the glands from the midline. However, the UABA and retroauricular approaches in particular are facilitators of selective lateral neck dissection. The central dissection of the neck can be done with the 4 approaches.

Robotic SurgeryRobotic procedures using the Da Vinci Surgical System (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) can provide a three-dimensional view with 10× to 12× magnification, which facilitates the identification of the parathyroid glands and the recurrent laryngeal nerve. (RLN). Unlike endoscopic procedures, robotic procedures offer vision stability and the possibility to simultaneously use 3 instruments with finer movements, since the system eliminates hand tremors. At the same time, the use of innovative instrumentation with the possibility of 360° movement provide greater freedom and delicacy during tissue manipulation.12,72

However, the operative time of endoscopic procedures, and especially robotic techniques, is significantly greater than that of conventional procedures due to the greater dissection time for the skin flap in cases in which gas is not used and the greater time necessary for robot docking (43.5min on average).73–77 The total surgical time of these procedures can decrease with experience and the familiarization of the surgical team with robot docking. In the largest study on this subject in the United States, Kandil et al. showed a decrease in the total operative time from 122 to 104min after the completion of 45 cases (P=.02); likewise, there was a significant increase (37min) in the total operative time in patients with BMI >30kg/m.

Although the number of complications between normal weight and overweight patients were similar, their data highlight the technical challenges that can be expected in obese patients.

The high cost is one of the biggest drawbacks for the current implementation of robotic surgery. Moreover, it is always necessary to bear in mind that these procedures are generally technically difficult and require a long learning curve, which can represent a problem in terms of patient safety.1,78,79 By and large, it has been demonstrated that remote access surgery under current conditions is not cost-effective, since the procedure is longer and more expensive compared to conventional thyroidectomy. With the development of new robot-assisted surgical devices and the opening of markets to new platforms (with the expected reduction in price of robotic arms), the disadvantage presented by the cost of robotic procedures may be resolved in the future.

Indications and ContraindicationsThe indications for MIES vary according to the experience of the surgeon, volume of the hospital where it is performed, disease state and approach to be used.1 In general, some of the indications for the use of these procedures are benign thyroid nodules and even follicular neoplasms less than 5cm in diameter.12,13 Cases with differentiated thyroid carcinoma, presence of muscle invasion or lymph node metastasis in the central or lateral compartments require special consideration, as the use of MIES is controversial in these patients.1 In the transoral approach, the size of the tumor or the thyroid gland itself can influence the surgical indication because it is difficult to remove a large surgical piece through a small oral incision. The exclusion criteria identified until now for endoscopic and robotic MIES include macroscopic extrathyroid extension, large conglomerates of metastatic lymph nodes with invasion to the surrounding structures, giant intrathoracic goiter, history of surgery or radiation of the neck and distant metastasis.12,13 Large goiters with Grave's disease or Hashimoto's thyroiditis may be relative contraindications due to a theoretical increase in the risk of intraoperative bleeding because of the fragility of the thyroid tissue.

Surgical and Oncological Results of Remote-access Minimally Invasive Cervical Endocrine Surgery (MIES)MorbidityThe excellent esthetic result is the most important reason for patients and surgeons to choose remote-access procedures. The esthetic result is obviously superior after remote-access MIES thyroidectomy compared to conventional surgery.12,58,76 Likewise, long-term esthetic satisfaction after maturation of the scar is also significantly greater in this type of approach than in conventional cervical approaches.37,58,80

Gasless transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy, compared to conventional surgery, resulted in better subjective recovery of voice and better results for acoustic parameters in terms of voice tone.81,82 However, one study reported similar postoperative voice results when comparing transaxillary and conventional thyroidectomy.83 Comparative prospective studies evaluating the function of voice after these procedures are necessary to be able to have solid results. Postoperative swallowing after endoscopic/robotic thyroidectomy has also been evaluated in 3 studies, but the results were not conclusive.82,84

Pain and sensory disturbance in the anterior thoracic area are more intense and last longer after gasless transaxillary thyroidectomy than after conventional thyroidectomy.85 Other studies do not report differences between subjective early postoperative pain in the robotic transaxillary approach compared to the conventional method.86,87

Health-related quality of life after transaxillary robotic thyroidectomy, including physical, psychological and social well-being, was similar to that of patients undergoing conventional thyroidectomy.88

In meta-analyses reporting on post-MIES complications using remote access for thyroidectomy, RLN palsy and hypoparathyroidism showed no significant differences between robotic and conventional thyroidectomy.73–77 However, in the subgroup analysis, transient RLN palsy was greater in the robotic procedure compared to the conventional technique.74 RLN injury in particular was more frequent at the beginning of the learning curve and for surgeons with low patient volumes.12,13

It is important to note that, although multiple reports evaluating the feasibility and safety of remote access approaches have been published in the literature, the frequency of complications is potentially higher than reported, especially considering that the learning curve is prolonged and particularly in cases of surgeons at low-volume hospitals. These approaches must be considered surgically challenging techniques. Serious complications have been reported, such as esophageal and tracheal injuries, airway compromise due to hematomas and even serious CO2 embolisms.

To obtain successful surgical results during the implementation of these techniques, an appropriate training program is essential, in addition to strict selection criteria. Patient safety should be the first priority to be monitored and considered at all times; above all, the possibility of conversion to an open procedure should be discussed prior to surgery.1,24

Learning Curve and Surgical TimeA comparative study by Lee et al. described the superiority of robotic thyroidectomy versus endoscopic thyroidectomy in terms of operative time, lymph node dissection and learning curve.89,90 However, for both procedures, the operative time gradually decreased as experience increased and stabilized after 35–40 cases for robotic thyroidectomy and 55–60 cases for endoscopic thyroidectomy.89,90 In another prospective multicenter study, the results of robotic total or subtotal thyroidectomy were compared between an experienced surgeon and 3 inexperienced surgeons, resulting in longer operative time and greater frequency of complications for inexperienced surgeons.79 However, once the inexperienced surgeons had performed 50 total thyroidectomy procedures or 40 subtotal procedures, both the operative time and the number of complications were similar to those of the expert surgeon.79 Research from the United States also supports that at least 40 cases are needed to overcome the learning curve in remote-access thyroidectomy.69

Oncologic ResultsConsidering the previously described advantages of these approaches, which are striking for any type of procedure at the cervical level, the use of these techniques has recently been expanded to lateral neck dissection for thyroid cancers with metastasized lateral compartment lymph nodes. Very recent reports have shown that robotic or endoscopic lateral dissection of the neck can be conducted through transaxillary unilateral (UABA) and retroauricular approaches.72,91,92 There is also a study on lateral neck dissection performed by BABA with insufflation of CO2.93 However, to date, we do not know of any long-term follow-up study after endoscopic/robotic lateral neck dissection, so its oncological safety has not been proven.

Oncological results are essential during the treatment of thyroid cancer and should not be overlooked or ignored in favor of esthetic or functional results. Despite this, the literature on oncological results evaluated by locoregional recurrence and disease-free survival after these procedures is very limited. Only 3 studies evaluate oncological results (disease-specific survival and recurrence rates) and obtain similar results when comparing robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy and conventional thyroidectomy; however, the studies are retrospective and the follow-up period was short.94–96 Therefore, prospective studies with long-term follow-ups and larger patient series are essential to provide firm long-term oncological results these approaches.

It is important to indicate the limitations of this review. Although PubMed covers the majority of the scientific bibliographic information, there are other databases and unpublished literature that may contain more information about MIES. There are no uniform guidelines to standardize remote-access thyroid surgery, and individual protocols are used at each institution. However, there are recommendations from different associations, such as the American Thyroid Association (ATA), which recommend rigorous patient selection prior to the implementation of these procedures, with strict inclusion/exclusion criteria and absolute contraindications for these approaches. In general, the ideal patient is thin, with a unilateral solitary nodule less than 3cm in diameter, who wants to avoid a scar on the neck.1

ConclusionsRemote-access cervical endocrine surgery is feasible and comparable, in general terms, to conventional transcervical procedures for benign pathologies, obtaining excellent esthetic results. However, prior to the implementation of these techniques, it is necessary examine their disadvantages in terms of longer operating time, cost and technical difficulty. In addition, training programs should be considered essential, with a long learning curve and strict selection criteria, while ensuring that patient safety is closely monitored. In addition, long-term prospective studies are required to evaluate the oncological results of this type of minimally invasive procedures.

Conflict of InterestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Vidal O, Saavedra-Perez D, Vilaça J, Pantoja JP, Delgado-Oliver E, Lopez-Boado MA, et al. Cirugía endocrina cervical mínimamente invasiva. Cir Esp. 2019;97:305–313.