Splanchnic aneurysms are rare, with an estimated incidence of 0.1%–2%. The most common presentations are located in the splenic artery (60%), followed by the hepatic artery (HA) (20%). HA aneurysms are mainly extrahepatic (75%–80%) and affect the common hepatic artery (63%); aneurysms of its branches are less common (23% right hepatic artery [RHA], 5% left hepatic artery, 4% bilateral).1

The main cause of true aneurysms is atherosclerosis.1–3 However, the percentage of pseudoaneurysms is increasing due to the generalization of percutaneous and endoscopic techniques, while their development secondary to inflammatory and/or infectious processes is unusual2–8 Unlike aneurysms, pseudoaneurysms grow relatively quickly, making early diagnosis and treatment important.

We present a case of RHA pseudoaneurysm (RHApA) secondary to cholecystitis:

The patient is a 46-year-old Asian woman with a history of biliary colic managed with traditional Chinese medicine. She consulted for abdominal pain and melena. On examination, she presented discomfort on palpation in the mesogastrium, with no peritonism. Analytically, she presented anemia, slightly elevated transaminases and mild neutrophilia, with no leukocytosis.

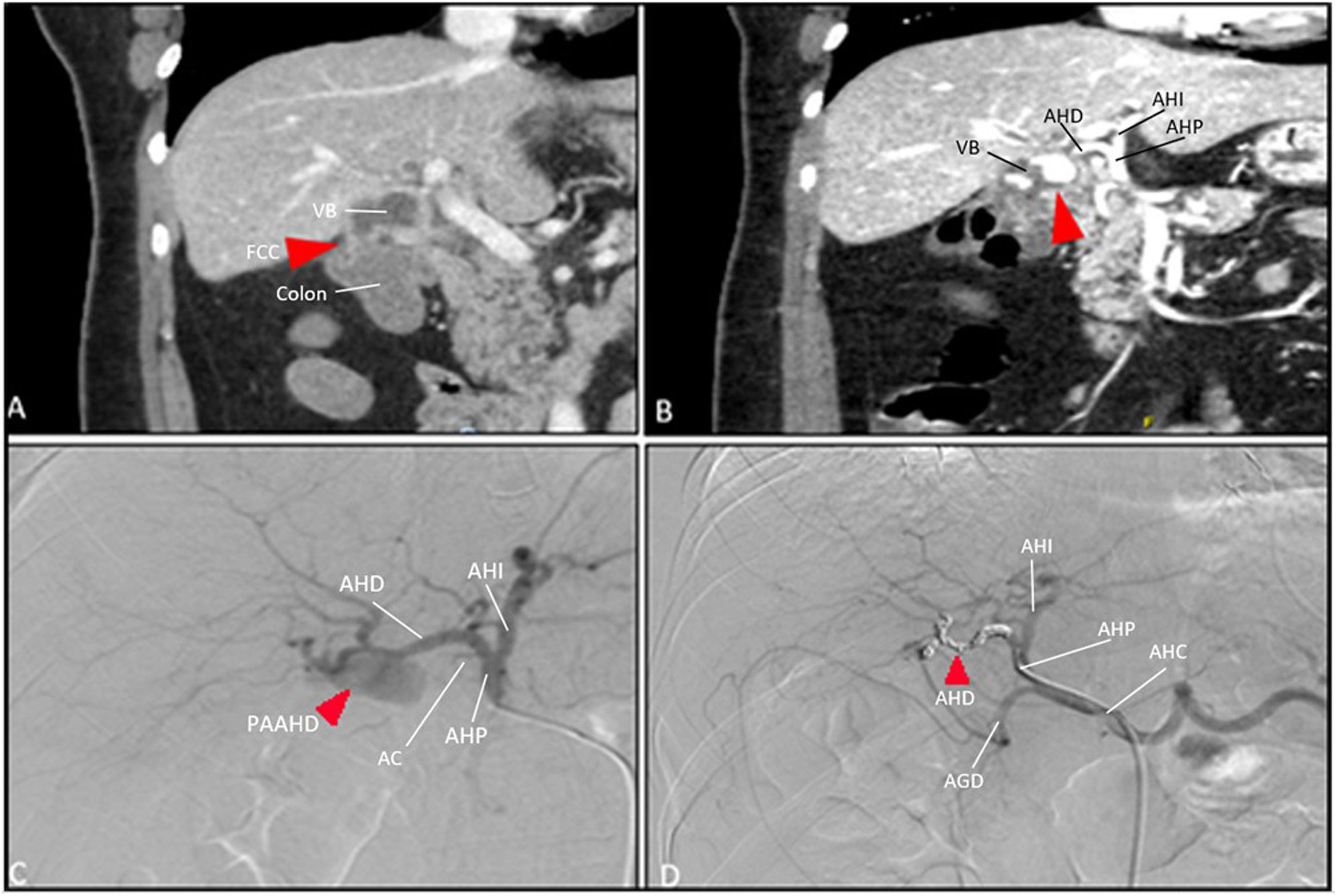

The Glasgow-Blatchford9 score showed a high risk of upper gastrointestinal bleeding (10 points). Gastroscopy was performed, showing no evidence of active bleeding. Computed tomography (CT) found exacerbated chronic cholecystitis. Within 48 h, she presented rectal bleeding that required transfusion, and CT angiography revealed a cholecystocolic fistula with no signs of active bleeding (Fig. 1A). On the 6th day of hospitalization and due to hemodynamic instability, the CT angiography was repeated, which showed active hemorrhage within the gallbladder (Fig. 1B). Urgent arteriography was indicated, demonstrating a RHApA (Fig. 1C), which was embolized with coils (Fig. 1D). Subsequently, another CT scan confirmed the exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm and correct bilateral hepatic perfusion. Liver function remained stable, with no laboratory abnormalities for bilirubin or transaminase levels. An exploratory laparotomy was performed 4 days later, which confirmed the presence of the cholecystocolic fistula and a communication between the HA and the gallbladder fundus; the coils were also observed inside the gallbladder lumen. Standard cholecystectomy was performed with suture of the cholecystocolic fistula using interrupted stitches. The postoperative period was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on the 10th day. The pathology report confirmed chronic cholecystitis.

(A) Acute cholecystitis over chronic cholecystopathy associated with cholecystocolic fistula; (B) active hemorrage in the gallbladder; (C) RHApA; (D) post-embolization arteriography with coils. GB = gallbladder; CCF = cholecystocolic fistula; LHA = left HA; HAP = HA proper; CA = cystic A; CHA = common HA; GDA = gastroduodenal A.

The diagnosis of hepatic artery aneurysm is usually incidental, and abdominal and/or lumbar pain are the main associated symptoms.1 The risk of rupture is greater in pseudoaneurysms.1,3 Quincke’s classic triad,4 consisting of pain in the right hypochondrium, gastrointestinal bleeding and jaundice due to hemobilia occurs in less than one-third of patients. The general incidence of rupture is around 25%, with mortality rates between 20% and 70%, depending on the series.1 In addition, the fibrinolytic action of bile favors the development of hemorrhagic shock. Although arteriography is the gold standard,4,8 the diagnostic test of choice is CT angiography, as it is less invasive and has high sensitivity and specificity.2,3,10 As this is an infrequent pathology, there is no consensus on management, but treatment is recommended for all pseudoaneurysms regardless of size or symptoms due to the increased risk of rupture.1,3

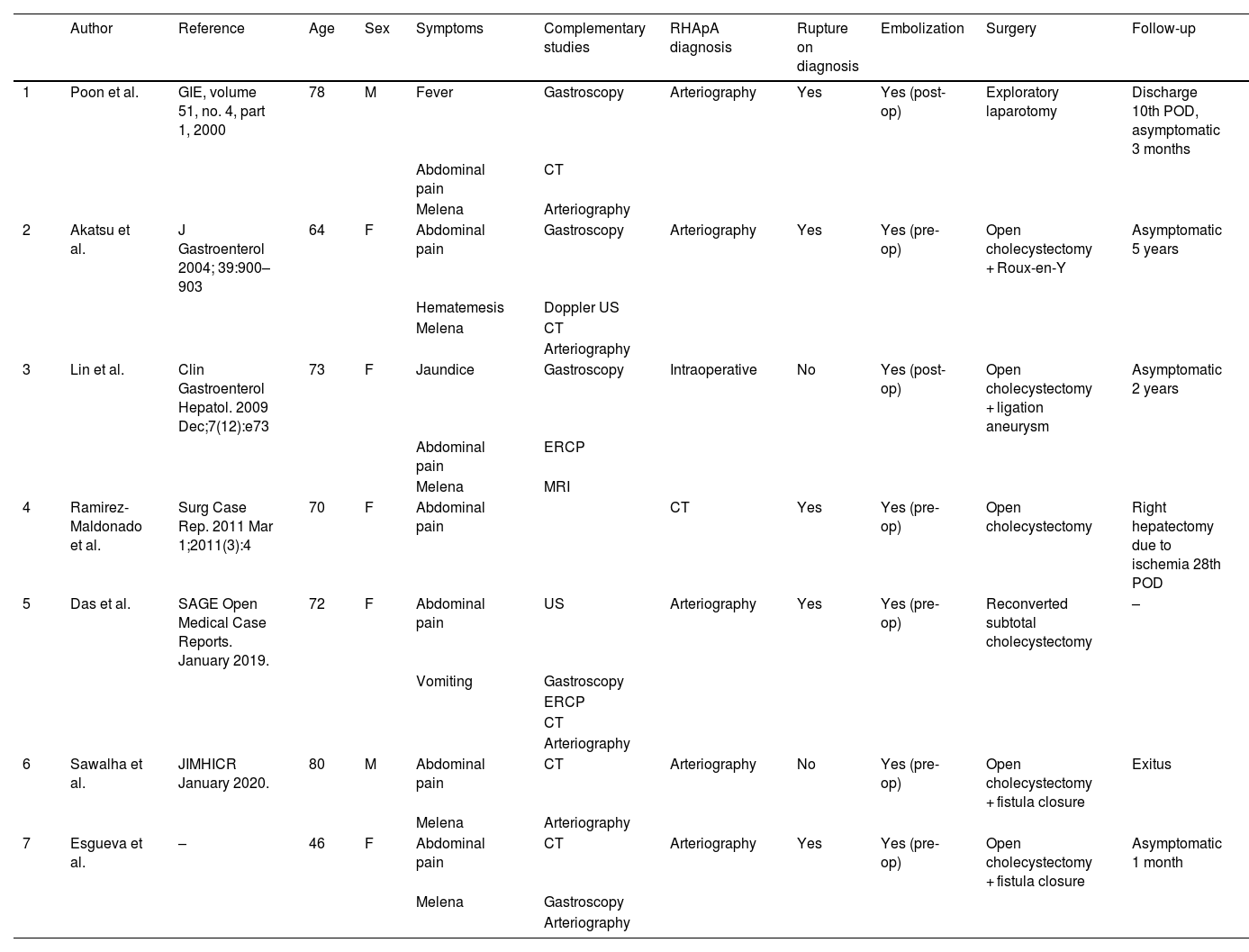

The presence of a cystic artery pseudoaneurysm (CApA) in the context of cholecystitis is a rare condition. It has been suggested that visceral inflammation adjacent to the vascular wall can cause injury to the adventitia and thrombosis of the vasa vasorum,4,10 contributing to the appearance of pseudoaneurysms. In a recent review, Patil et al.10 have reported a total of 59 CApA. To our knowledge, RHApA seem to be even more exceptional, as we have only found 6 cases published in the international literature (Table 1).2,4–8

Cases published in the international literature of RHApA in the context of cholecystitis. M = male; F = female; US = ultrasound; CT = computed tomography; ERCP = endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; pre-op = before surgery; post-op = after surgery; POD = postoperative day.

| Author | Reference | Age | Sex | Symptoms | Complementary studies | RHApA diagnosis | Rupture on diagnosis | Embolization | Surgery | Follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Poon et al. | GIE, volume 51, no. 4, part 1, 2000 | 78 | M | Fever | Gastroscopy | Arteriography | Yes | Yes (post-op) | Exploratory laparotomy | Discharge 10th POD, asymptomatic 3 months |

| Abdominal pain | CT | ||||||||||

| Melena | Arteriography | ||||||||||

| 2 | Akatsu et al. | J Gastroenterol 2004; 39:900–903 | 64 | F | Abdominal pain | Gastroscopy | Arteriography | Yes | Yes (pre-op) | Open cholecystectomy + Roux-en-Y | Asymptomatic 5 years |

| Hematemesis | Doppler US | ||||||||||

| Melena | CT | ||||||||||

| Arteriography | |||||||||||

| 3 | Lin et al. | Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009 Dec;7(12):e73 | 73 | F | Jaundice | Gastroscopy | Intraoperative | No | Yes (post-op) | Open cholecystectomy + ligation aneurysm | Asymptomatic 2 years |

| Abdominal pain | ERCP | ||||||||||

| Melena | MRI | ||||||||||

| 4 | Ramirez-Maldonado et al. | Surg Case Rep. 2011 Mar 1;2011(3):4 | 70 | F | Abdominal pain | CT | Yes | Yes (pre-op) | Open cholecystectomy | Right hepatectomy due to ischemia 28th POD | |

| 5 | Das et al. | SAGE Open Medical Case Reports. January 2019. | 72 | F | Abdominal pain | US | Arteriography | Yes | Yes (pre-op) | Reconverted subtotal cholecystectomy | – |

| Vomiting | Gastroscopy | ||||||||||

| ERCP | |||||||||||

| CT | |||||||||||

| Arteriography | |||||||||||

| 6 | Sawalha et al. | JIMHICR January 2020. | 80 | M | Abdominal pain | CT | Arteriography | No | Yes (pre-op) | Open cholecystectomy + fistula closure | Exitus |

| Melena | Arteriography | ||||||||||

| 7 | Esgueva et al. | – | 46 | F | Abdominal pain | CT | Arteriography | Yes | Yes (pre-op) | Open cholecystectomy + fistula closure | Asymptomatic 1 month |

| Melena | Gastroscopy | ||||||||||

| Arteriography |

According to the review of experiences reported on RHApA due to cholecystitis,2,4–8 mean patient age is 72.8 years, with a predominance of females (3:1). The predominant symptom is abdominal pain (100%),2,4–8 followed by UGI bleeding (melena 66.6%,2,4–6 hematemesis 16.6%5). Fever is infrequent (16.6%).4 Presentation as cholecystobiliary fistula (Mirizzi syndrome grade V) occurred in 2 patients (33.3%).2,4 In 3 cases (33.3%), bleeding through Vater’s papilla was observed on gastroscopy.5,6 The diagnosis of RHApA was made by CT in one case7 (16.6%), while 66.6% required arteriography.2,4,5,8 In one case, the pseudoaneurysm was found intraoperatively.6 Preoperative embolization was performed in 66.6%,2,5,7,8 and in the other 2 cases during the postoperative period.4,6 Cholecystectomy was completed in 83.3% of cases.2,5–8 In one case of cholecystoduodenal fistula, embolization was technically impossible to perform due to uncontrollable bleeding, requiring postoperative embolization of the RHApA and deferred cholecystectomy.4 One patient died during cholecystectomy due to uncontrollable bleeding, despite having undergone prior angioembolization. This patient also had a cholecystocolic fistula.2

Preoperative embolization of both CApA and RHApA reduces the risk of intraoperative bleeding, which may facilitate dissection during cholecystectomy. However, the need to perform cholecystectomy in all cases is the subject of debate. Although there is a risk of gallbladder or even hepatic ischemia, some authors advocate avoiding it in patients with high surgical risk.10

Thus, RHApA are an exceptional entity in the context of cholecystitis, whose diagnostic suspicion must be established in patients with acute cholecystitis and gastrointestinal bleeding. The scarcity of bibliographic references prevents us from establishing a therapeutic algorithm, although initial actions to stabilize the patient are required. Angioembolization presents satisfactory results as an initial measure, stopping bleeding and reducing the risk of intraoperative hemorrhage during cholecystectomy.

FundingThis article has received no specific funding from public, commercial or non-profit sources.

Conflicts of interestsNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.