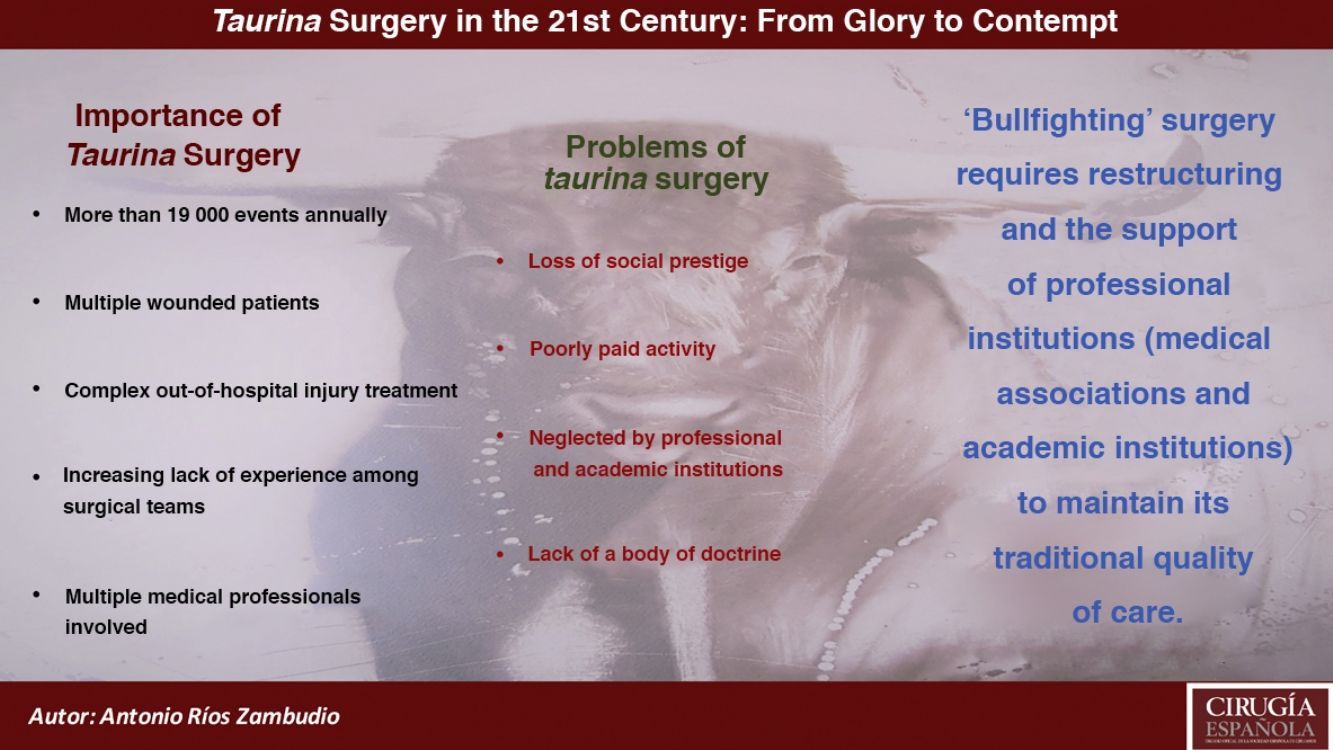

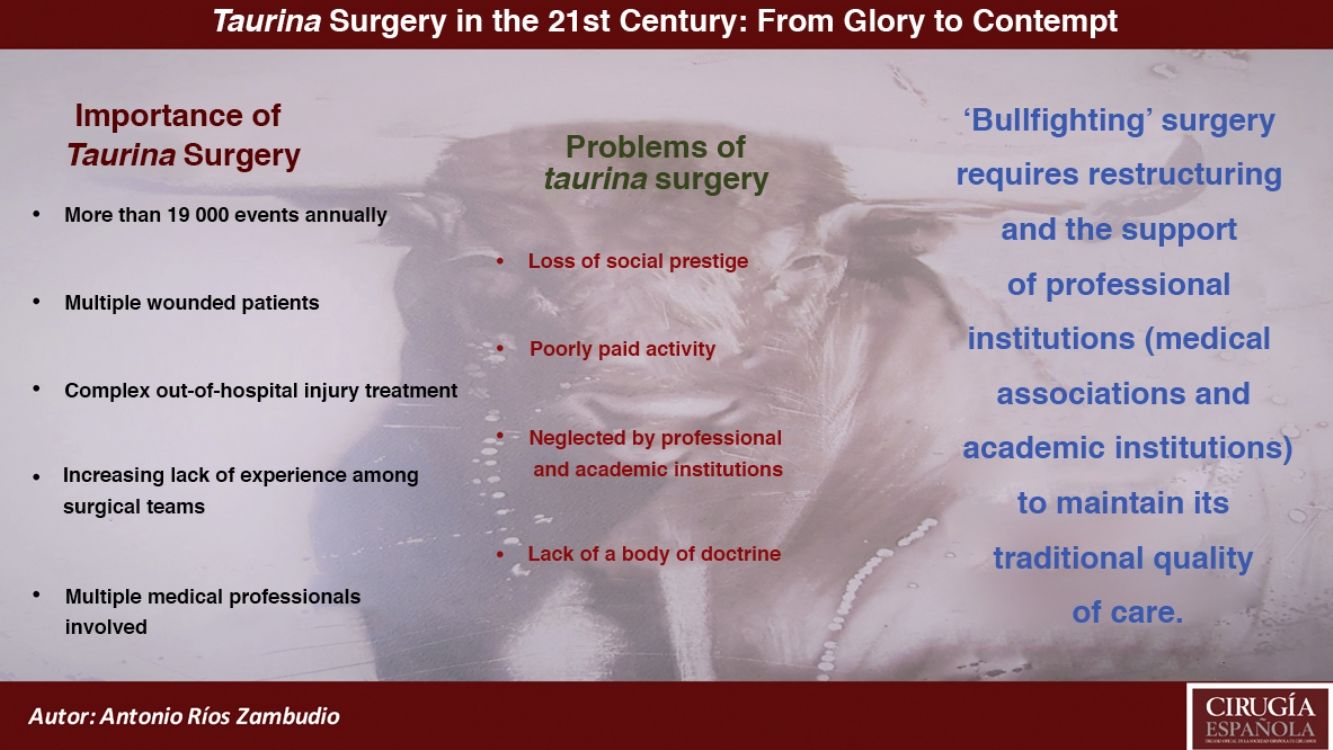

Bullfighting surgery has gone from being something that the surgeon could be proud of in any setting to being an activity frowned upon from a social point of view, and even in our surgical guild. However, popular bullfighting festivities are still very frequent, with thousands of injured each year, some of them serious. Currently, health care in bullfighting festivals is immersed in a complex problem mainly due to four factors: 1) social and professional discredit; 2) poorly paid professional activity; 3) neglect by professional and academic institutions; and 4) lack of a specific body of doctrine. All this has led to the health care teams in bullfighting surgery being less and less professionalized and more inexperienced, to problems of professional intrusion. Consequently, there is a direct impact on the quality of care provided and on the morbidity and mortality rates of injured participants, with the legal implications that this entails. A restructuring of this situation and the support of professional institutions, especially Medical Associations, and academic institutions, is necessary.

La cirugía taurina ha pasado de ser algo de lo que el cirujano presumía en todos los ámbitos de su entorno a ser una actividad mal vista desde el punto de vista social e incluyó en nuestro gremio quirúrgico. Sin embargo, los festejos taurinos populares siguen siendo muy frecuentes, con miles de heridos cada año, algunos de ellos graves. Actualmente, la atención sanitaria en festejos taurinos está inmersa en una problemática compleja debido principalmente a cuatro aspectos: 1) desprestigio social y profesional, 2) actividad profesional mal pagada, 3) abandono por las instituciones profesionales y académicas, y 4) falta de un cuerpo de doctrina específico. Todo esto está conllevando a que los equipos de atención sanitaria en cirugía taurina sean cada vez menos profesionalizados y más inexpertos, y a problemas de intrusismo profesional. Esta situación está repercutiendo directamente en la calidad asistencial prestada y en la morbimortalidad de la población herida, con las implicaciones legales que conlleva. Es necesaria una reestructuración de esta situación y el apoyo de las instituciones profesionales, sobre todo de los Colegios de Médicos, y de las instituciones académicas.

Taurina or ‘bullfighting’ surgery has gone from being something that surgeons could be proud of in all areas of society to being almost a secretive activity that is generally frowned upon, both socially and even within our surgical profession. During the 20th century, being a head bullring surgeon meant prestige, social and political recognition, while in many instances it became the socio-political springboard for developing a private medical practice and advancing in surgery services at public hospitals. However, the current sociopolitical tendency is to reject everything involved with the world of tauromachy.

The importance of bullfighting surgery in medicineIt is a mistake to trivialize this type of healthcare given the great impact it has on public healthcare and the large number of medical professionals, especially surgeons, who are involved in these events.1–7 There are four facets that should be highlighted to understand this importance:

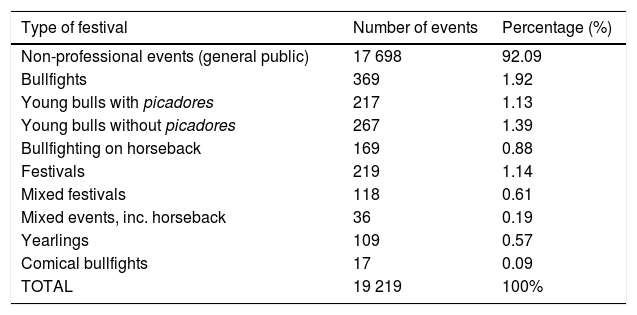

First of all, there are numerous bull-related events in Spain. Frequently, there is a tendency to minimize the impact of this healthcare activity, since the perception is that it is limited to professional bullfights. However, the number of organized bullfighting events or their variants represent a low percentage of bull-related events as a whole. According to the latest ministerial record,2 the volume of annual taurina festivals in Spain is 19 219.1,2 The vast majority (92.09%; n = 17 698), are popular bull-related festivals with participation of the general public,1 while professional bullfights represent only 1.92% (n = 369), bullfights with young bulls and picadores on horseback 1.13% (n = 217), and bullfights with young bulls without picadores 1.39% (n = 267) (Table 1).2

Bullfighting festivals held in Spain.

| Type of festival | Number of events | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Non-professional events (general public) | 17 698 | 92.09 |

| Bullfights | 369 | 1.92 |

| Young bulls with picadores | 217 | 1.13 |

| Young bulls without picadores | 267 | 1.39 |

| Bullfighting on horseback | 169 | 0.88 |

| Festivals | 219 | 1.14 |

| Mixed festivals | 118 | 0.61 |

| Mixed events, inc. horseback | 36 | 0.19 |

| Yearlings | 109 | 0.57 |

| Comical bullfights | 17 | 0.09 |

| TOTAL | 19 219 | 100% |

*Latest data published by the Ministry of Culture and Sports when this article was submitted; data from 2018.2

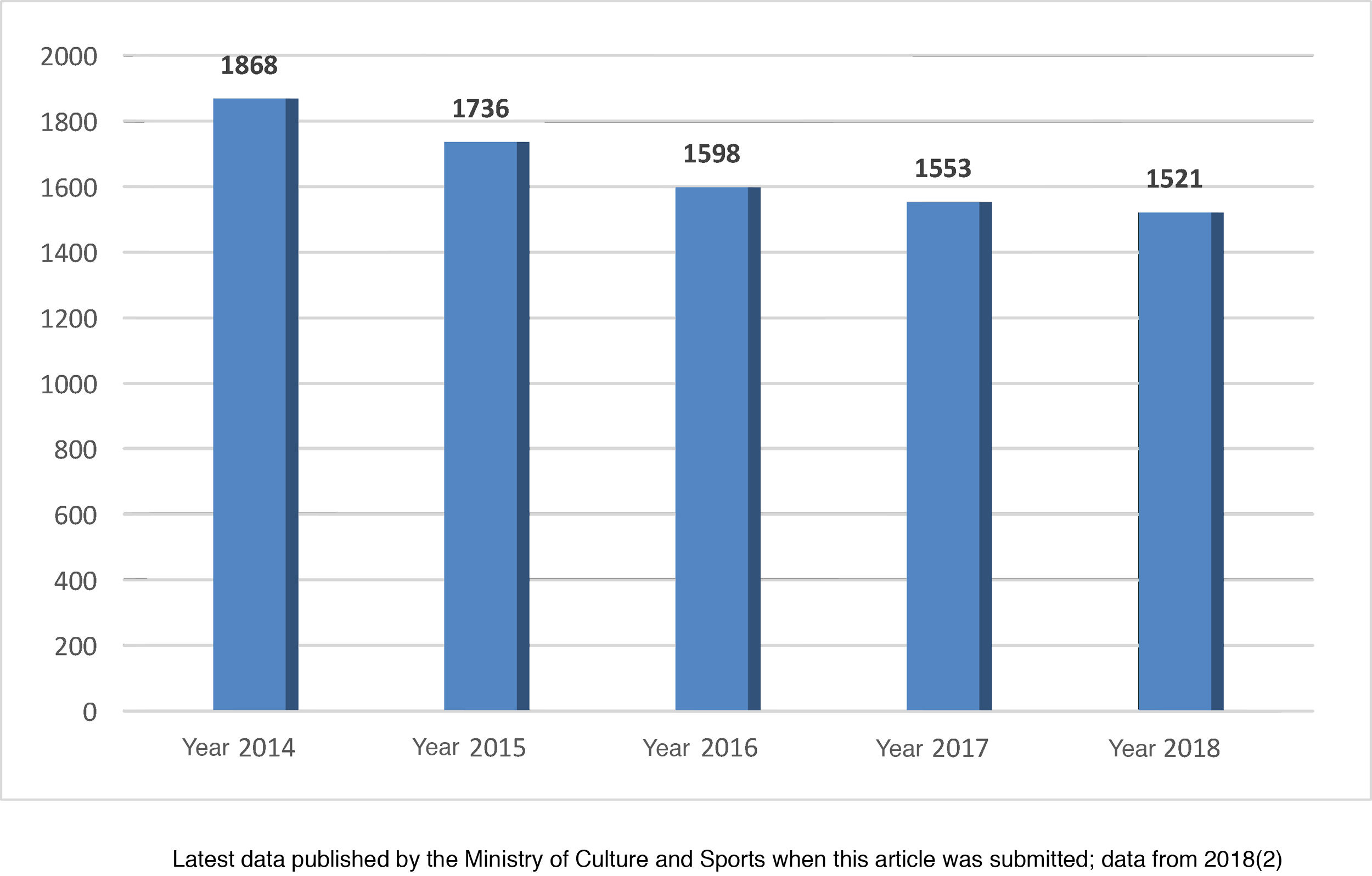

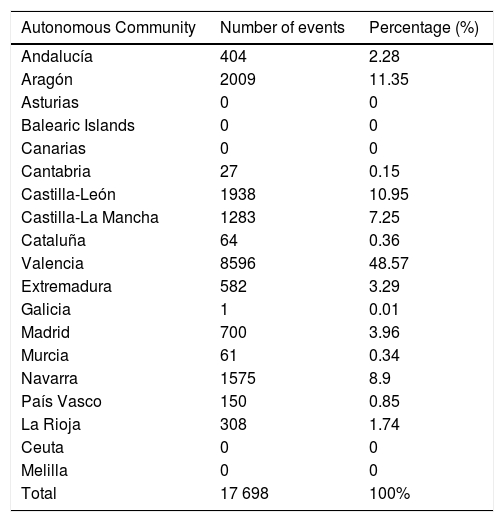

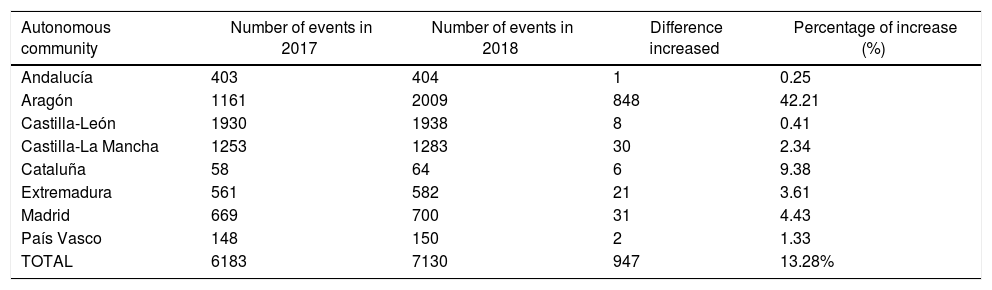

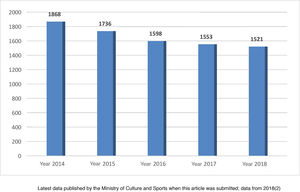

In addition, when the discussion arises about the decline of bullfighting celebrations,2,8 this almost always refers to professional events in bullrings. As shown in Fig. 1, in recent years there has been a progressive and constant decline in the total number of bullfighting festivals held in bullrings, currently standing at 7.91% of all of events,1,2 and only 1.92% are professional bullfights, or corridas. In contrast, popular bull-related festivals have not decreased or show small interannual fluctuations, and there is an overall upward trend (Table 2). Thus, although the last biennial report provided by the Ministry of Culture and Sports (2017–2018) shows a small drop in popular celebrations of 1.24% (17 920 in 2017 vs 17 698 in 2018), the in-depth analysis of the data shows that this was due to a specific situation that occurred in the Valencian Community during 2018, which led to the cancellation of 1119 local celebrations.2 In another eight regions of Spain, however, the total number of bullfighting festivals had increased by 947 compared to the previous year (Table 3).2 One must consider that the anti-bullfighting trend is more accentuated in areas where tauromachy either does not exist or is a residual activity. In contrast, in regions with a greater tradition of bull-related events, there is a rebound effect because this rejection is felt as an attack on their traditions, which has a revitalizing effect that increases both the number of bullfighting festivals and the number of toros bravos (fighting bulls) that participate in them.

Non-professional (general public) tauromachy festivals held in different Autonomous Communities of Spain.

| Autonomous Community | Number of events | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Andalucía | 404 | 2.28 |

| Aragón | 2009 | 11.35 |

| Asturias | 0 | 0 |

| Balearic Islands | 0 | 0 |

| Canarias | 0 | 0 |

| Cantabria | 27 | 0.15 |

| Castilla-León | 1938 | 10.95 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1283 | 7.25 |

| Cataluña | 64 | 0.36 |

| Valencia | 8596 | 48.57 |

| Extremadura | 582 | 3.29 |

| Galicia | 1 | 0.01 |

| Madrid | 700 | 3.96 |

| Murcia | 61 | 0.34 |

| Navarra | 1575 | 8.9 |

| País Vasco | 150 | 0.85 |

| La Rioja | 308 | 1.74 |

| Ceuta | 0 | 0 |

| Melilla | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 17 698 | 100% |

*Latest data published by the Ministry of Culture and Sports when this article was submitted; data from 2018.2

Autonomous communities in Spain that have seen an increase in the number of non-professional tauromachy events, according to data from the Ministry of Culture and Sports.

| Autonomous community | Number of events in 2017 | Number of events in 2018 | Difference increased | Percentage of increase (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Andalucía | 403 | 404 | 1 | 0.25 |

| Aragón | 1161 | 2009 | 848 | 42.21 |

| Castilla-León | 1930 | 1938 | 8 | 0.41 |

| Castilla-La Mancha | 1253 | 1283 | 30 | 2.34 |

| Cataluña | 58 | 64 | 6 | 9.38 |

| Extremadura | 561 | 582 | 21 | 3.61 |

| Madrid | 669 | 700 | 31 | 4.43 |

| País Vasco | 148 | 150 | 2 | 1.33 |

| TOTAL | 6183 | 7130 | 947 | 13.28% |

*Latest data published by the Ministry of Culture and Sports when this article was submitted; data from 2018.2

Second, we must be aware of the type of injuries caused by these events. In bullrings,1,2 the typical patient is a professional male bullfighter who is generally slim, young and in good health, and there is also an infirmary with an operating room. In local celebrations or fiestas, however, which are the majority of bull-related events, the typical patient is a person from the general population, who is not athletic and has generally consumed excessive amount of alcohol and/or other substances, that stands in front of these dangerous animals. There is also the added risk of the crowd, many of whom tend to flee and trample other participants. In other words, these are suboptimal injured patients in non-sanitary areas, where there is generally no hospital infirmary and resources are limited.1–4

Third, the medical teams at these bullfighting festivities are made up of increasingly younger and inexperienced medical professionals, who usually carry out this activity in the first years as fellows in order to earn extra income. However, it is a very demanding and sometimes extremely urgent activity that requires experienced surgeons.1,5–7

Fourth, it is necessary to address the volume of activity that this type of medical care implies. On the one hand is the number of surgeons involved. There are more than 19 000 annual celebrations,2 and at each the current legislation requires the presence of two qualified surgeons, one as head surgeon and the other as assistant surgeon.2 This situation is accentuated in the summer, and in July and August there are more than 1000 events held a day in Spain, requiring the involvement of more than 2000 surgeons every day. On the other hand is the number of injured patients. Although there are no official data, it should be noted that the population exposed to potential injuries reaches millions of people of all ages and sex each year. In this context, most of the festivities correspond with populations that celebrate their local patron saint festivals, which is usually a time of gathering of varying population groups, multiplying the resident population in these municipalities on the dates of the festivities.

Problems of bullfighting surgeryTaurina surgery is currently involved in a complex problem that directly affects the quality of care provided and indirectly affects the morbidity and mortality of those injured.1 Generally speaking, this can be broken down into four points:

- 1

Loss of social prestige

Socially, there is a general pro-animal mindset that has resulted in a negative attitude towards certain activities that are classically rooted in Spanish society, such as hunting and tauromachy. Furthermore, in certain ‘autonomous communities’ of Spain, bullfighting has been prohibited by law.1 However, we must also consider that areas with proposals to prohibit bullfighting are areas where this activity is already trivial.1 In populations with a bullfighting tradition, it is difficult to propose prohibition because of the social rejection that it entails and the loss of votes in the following elections by the political parties involved.1

- 2

Underpaid professional activity

Until a few decades ago, engaging in taurina surgery was a springboard for professional prestige and social recognition, and no one would consider charging for it. Furthermore, in most bullrings and important festivities, surgeons were not paid, yet the most prestigious medical teams were present. Currently, except in certain first-class bullrings, the situation is complex, since there are several celebrations where traditionally there was little or no pay, and where now there is no predisposition to go to work.

- 3

Neglect by professional and academic institutions

This is the great difference with the veterinary profession specialized in tauromachy, which is supported by veterinary professional associations in most autonomous communities of Spain, with job listings for bullfighting festivities and regulated veterinarian fees. However, in taurina surgery there is no such support or regulation by physicians’ associations. In addition, most institutions show neither their rejection of nor their support for this profession. The case of the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) merits comment, as this institution has contributed towards improving medical care and developing a high scientific quality in all its divisions and working groups. Nevertheless, bullfighting surgery is not on their radar and has been relegated to other institutions that have neither the prestige nor the quality that the AEC provides. It is necessary to contemplate the prejudices that could make a surgical activity like this (with the involvement of more than 2000 surgeons on certain days and millions of people exposed to potential injuries) not be endorsed by the AEC. It must be said that this is not only an institutional problem, but it is largely the fault of taurina surgeons, who, for whatever reasons, neither encourage nor favor AEC involvement.

- 4

Lack of a body of doctrine

Unlike any other super-specialty derived from General and Digestive Surgery, bullfighting surgery, despite its antiquity and centuries of history, lacks guidelines and a body of doctrine of its own. Three factors contribute to this situation:

- 1

Little scientific training in a high percentage of taurina surgeons. Excluding a small group of surgeons with specific medical training, it is very rare for bullfighting surgeons to have a related doctoral thesis, published scientific articles in high-impact journals, or be licensed by the National Agency for Quality Assessment and Accreditation (ANECA) for universities. This goes against being able to carry out research in this field and generate a body of doctrine, which is so necessary, especially when many new surgeons are currently being incorporated without specific training on this subject.1

- 2

Lack of support from scientific societies. This situation makes it difficult to develop specific guidelines. The creation of healthcare guidelines entails economic costs, and in the field of bullfighting surgery it would be very difficult for any company (pharmaceutical or otherwise) to provide funding. In addition, the lack of sponsorship of scientific societies restrains publishers, since this situation makes subsequent sales difficult and, therefore, usually entails financial losses. In this context, the classic type of publication by taurina surgeons is of little contribution, as it is typically full of folklore and ‘art’ terminology, often offering little science or scientific method.

In fact, an example of all these difficulties is seen in one of the few medical guidelines published on bullfighting festivals, which I was lucky enough to be able to edit, created with the support of 67 other surgeons from Spain, France, and Latin American countries with a tradition of bull-related events.1 The document presented all of the issues indicated above: 1) the lack of support from scientific associations meant that the guide was financed by municipalities and medical centers where bullfighting is popular (90%), and the remaining 10% came from donations from medical professionals of bullfighting surgery teams themselves; 2) the lack of specific scientific training meant that, in addition to the 67 professionals involved, another 33 surgeons who had been invited to participate ultimately left the project due to their inexperience in scientific writing. All this made the project difficult, and it was the involvement of surgeons with scientific experience that made it possible to finalize it with the quality standards of AEC guidelines.1

- 3

Lack of involvement in universities. This medical discipline is not taught at universities. Most universities dedicate at most a single chapter from general surgery teaching in the third year of medical school. In recent years, there have been isolated courses given on bullfighting surgery endorsed by certain universities, such as those held in Murcia,9 Santander10 and Valencia.11 In this context, the University of Valencia presented the first postgraduate degree in medical-surgical management of bull-horn injuries in 2019. These are quality courses that address important issues, but most focus on medical care provided during professional events in bullrings, which, as mentioned above, are a minority of all bull-related festivities held in Spain. The objective should be to focus on offering courses to be able to provide quality care for the vast majority of patients affected by bull-related injuries, most of which take place during locally organized festivities.9

So, ultimately, what motivates a surgeon to attend a tauromachy event as a medical professional? This is an honest question, especially when we consider all the difficulties involved in this healthcare activity:

- a)

Long work hours. The medical team must arrive at least one hour before the event to certify all the documentation, they must be present during the entire event, and afterwards they must complete the official documentation required according to current regulations, both national and regional.1

- b)

Work generally takes place on holidays.

- c)

Low economic remuneration

- d)

Little or no social appreciation

- e)

Little or no professional acknowledgement

- f)

Anti-bullfighting demonstrations. It is increasingly common to encounter anti-bullfighting demonstrations upon arrival at these events. This leads to confrontational situations with insults, graffiti, etc, that make it uncomfortable to carry out health activities.

With all these drawbacks, there are basically three situations that can be distinguished for why a surgeon may agree to work as surgeon at a bull-related event:

For social and professional prestige – This situation is increasingly becoming a minority, but some top-level professional bullrings and socially recognized bull-related festivals, such as the ‘Running of the Bulls’ (San Fermines) in Pamplona, continue to be prestigious events.

For social and family reasons – Some surgeons may have friendships or social and family commitments in certain regions with strong bullfighting traditions. However, this situation is becoming less and less common.

For financial reasons. Bullfighting surgery teams go to the vast majority of celebrations for the financial incentive. When the economic incentive is poor, the profile of the surgeon who attends the celebration is a recently finished surgery fellow with a precarious employment situation.

Medical ‘intrusion’ in taurina surgeryThe problems of bullfighting surgery mentioned above result in the lack of motivation of surgeons to attend these events, thereby favoring the intrusion of non-certified surgeons. Bullfighting surgery teams have been sued in several parts of Spain, especially in Castilla-La Mancha and Andalusia, for not being teams with certified surgeons.12,13 On other occasions, certain surgical teams have signed medical reports for several different events held simultaneously, emboldened by the classic laxity in the regulated control of medical teams.

All these irregularities are usually discovered when confronted by a seriously injured person, who cannot be managed by the transfer medical team at the event, and where no trained bullfighting surgeons have been hired. First of all, this situation has consequences for wounded individuals, resulting in sequelae or even death; second, there are consequences for the uncertified medical teams, who frequently end up in prison13; third, the authorities in charge of monitoring these celebrations (government delegate and Civil Guard), typically receive administrative sanctions and leave without pay; and finally, there are political repercussions, since most of the event organizers are city councils or public institutions. Consequently, all this gradually leads to more rigorous regulations and mistrust of surgical teams. To provide an example, I personally had the opportunity to attend an event as surgeon in a town that had had a previous intrusion scandal, and the situation was cold and tense, with thorough administrative monitoring. As the celebration lasted five hours, I can honestly say that it was the only time in my life that I have had to be escorted to the restroom by Civil Guards.

Conflicts between bullfighting surgeonsAnother unfortunate issue is the confrontation between bullfighting surgeons, which in many cases ends up in the press.14 Without getting into controversial details, since all those involved are right to an extent, we surgeons should be able to manage bullfighting surgery without fighting or arguing, which generates distrust towards bullfighting surgery teams.

One can perfectly understand the frustration of surgeons who are asked for a second opinion a few days after an initial surgery and encounter complex wounds presenting poor evolution that require reoperation. On the other hand, one can also understand the problems of surgeons who initially treat these patients and are faced with complex and highly contaminated wounds. If we add to this the fact that most healthcare centers and institutions that monitor these wounds do not have sufficient experience in their management, it is common for these wounds to require reoperation. This is especially true when we consider that patients who ask for a second opinion are usually those who evolve unfavorably.

When these news items are reviewed,14 there are always recriminations that focus on two factors: the poor working conditions at the point of initial care, and the lack of experience of the surgical teams. However, one fundamental issue is not addressed, and that is that the germs are not acquired as a consequence of the initial treatment, but instead because bull horns contain millions of germs, which are the main cause of poor evolution.1 In fact, we should be reminded that bullfighting surgeons were one of the first groups to raise a monument to Fleming, in the vicinity of the Las Ventas Bullring in Madrid, in recognition of the transcendence of penicillin to fight against the germs of these wounds.

All these controversies should be avoided, and especially their diffusion in the press, which generates distrust towards bullfighting surgery teams. In any case, it is necessary to regulate and control taurina surgery so that it is carried out legally and with quality of care, as is to be expected in any medical activity. It is also necessary to be reminded that the head surgeon of the taurina medical team gives his/her consent and informs the authorities that the necessary healthcare requirements have been met for the event (medical supplies, complete medical equipment, etc). Therefore, if the means are precarious, the surgeon is responsible.1 For this reason, when reading the classic book by José Bergamin, The Silent Music of Bullfighting,15 and the bullring infirmary is described as the “little room that only had a small window and prison bars, which barely let in the dusty air…” , and taurina surgeons con identify with this setting to a greater or lesser degree, we must remember that we legally accept, in the presence of the government delegate, that the infirmaries are adequate and present the appropriate conditions to conduct medical treatments.

What conditions should a taurina surgery team know how to treat?The range of tauromachy events is enormous,1 and therefore the habitual simplification limited to typical goring in the groin is dangerous. The reality is very complex and requires us to know the type of event we are attending as surgeons.1,16–18 In some bullfighting festivities, such as the toro embolado, burns are frequent, and it is necessary to be prepared and have the means for an initial effective treatment. The exact opposite situation is given during bull-related events at sea, where, instead of burns, we must be prepared for drownings. In festivities that include ‘running of the bulls’, there are frequent avalanches of fleeing people, and participants can be crushed. In other words, the range of potential injuries is very broad, and for this reason it is essential to precisely understand the activities that take will place and the means necessary to manage potential patients.1,19–21

Finally, it should be noted that the success of the medical care provided for patients affected in tauromachy events involves comprehensively treating the wounded. Remember that the initial emergency care is aimed at saving the life of the patient. However, the final prognosis depends on subsequent continued care.1 Thus, physical sequelae are frequent, especially the loss of mobility of the lower limbs, associated with complex bull-horn penetration wounds and bone injuries. However, psychological sequelae are also frequent as a consequence of the post-traumatic stress that is generated in many of these patients.1 For this reason, multidisciplinary teams are important where, in addition to the surgeon, the anesthetist and the nursing staff, a physical therapist and clinical psychologist are included for the subsequent management of these patients. It is also important to have a discussion with the veterinarian present before the event for information on potential injuries based on the morphotype, breed and age of the animals participating in the festivities.1

Legal implications of bullfighting surgeryAs in society at large, bullfighting surgery is also affected by the current situation where people will litigate about almost everything. In these tauromachy activities, where many people are injured and a large population is involved, many legal complaints are filed and, therefore, the head surgeon of the bullfighting surgery team becomes involved in the legal process.1 Most of the lawsuits are filed against the promoters and organizers of the event, but the head surgeon of the taurina surgery team always has to go to court to testify about the injury that occurred, etc. All this makes it necessary to keep a record of all the patients treated at these events, since the judicial processes usually are delayed by at least two years. Keep in mind that formal defects, deficiencies in the bullfighting surgery teams, etc, can lead to indirect sanctions for the bullfighting surgery team.

The uncertain future of taurina surgeryBullfighting surgery is linked to the bull-related events being held, and therefore its future is directly related to the future of tauromachy.1,2 Currently, anti-bullfighting legislation has emerged in different countries and regions. However, in areas with bullfighting traditions, the social support is quite significant, and anti-bullfighting groups are a minority, although it will be necessary to wait for the next few decades to get an idea of the importance that they may actually reach.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to a peculiar situation in 2020, as it has resulted in almost total cessation of bullfighting events, and especially of popular local festivities where it is impossible to guarantee social distancing. This abrupt cessation of the entire business chain linked to tauromachy has led to the definitive closure of several ranches and related service companies. Likewise, the chain of financing for the festivities has also been broken. For this reason, when we return to a normal social situation where these bull-related festivities could be held again, the recovery of this sector is uncertain.

Finally, it must be remembered that the organization of bullfighting events is very expensive. The cessation of the activity for more than a year and the disappearance of tauromachy companies and cattle ranches will make this type of festivities more expensive, leading to their disappearance in some instances. In many bullrings and towns, bullfighting events have not disappeared due to a lack of fans, but rather due to lack of financing that resulted in businessmen not organizing events in these forums.

Current needs of taurina surgeryThis is a time of uncertainty for bullfighting surgery and changes are necessary for quality healthcare to exist, since the current situation has a direct impact on the quality of care provided and indirectly on the morbidity and mortality of the injured population.1 Although the solutions are not easy, and the proposals can be varied, along general lines the great needs of bullfighting surgery that need to be addressed are:

- 1

Regulation of the medical professionals involved. It is not easy to address this issue, but this would avoid professional intrusion and guarantee that bullfighting festivals hire surgeons with the appropriate qualifications. While not comparable, the solution provided by veterinarians has solved this issue in their collective, and in several autonomous communities of Spain the veterinary associations generate job listings for bullfighting events. Medical associations may possibly be the best option to regulate this, providing a list of surgeons who have registered to work at these events.

- 2

Recognition by scientific societies. In this case, it would be essential to incorporate a specific division in the AEC, just like other divisions in the organization. All the divisions and working groups of the AEC have achieved improvements in healthcare and high scientific quality.

- 3

Creation of a body of doctrine. Although guidelines on medical care at international bullfighting festivals has been published in recent years, it is necessary to monitor and update such knowledge.1 For this reason, as in any other super-specialty derived from General Surgery and the Digestive System, taurina surgery requires institutional support in order to create an updated body of doctrine and clinical guidelines, without depending on individual efforts or those of a single group. Furthermore, this situation would generate the minimum conditions necessary to carry out research in this field.

- 4

Regulated fees for the activity. It is necessary to regulate the fees to be received for providing healthcare at bullfighting festivals; at the very least, a minimum fee should be established according to the type of event and its duration. Currently, fees paid for these events are very variable; meanwhile, for a high percentage of events, there is no record of any official payment. All this should be regulated and clarified to avoid these services being underpaid, while at the same time avoiding untaxed irregular payments.

- 5

Basic training in medical care for bull-related injuries should be included in university studies. Medical school teaching must include basic theory and practices to acquire the basic skills necessary for the management of these patients, both for initial urgent care as well as subsequent continuous care. Training during medical school would improve the management of these patients at all levels, correcting not only the basic deficiencies in initial care, but also in subsequent healthcare. At the very least, this training should be provided by the universities of the autonomous communities in where bullfighting events are held.

The author has no conflict of interests to declare.

Thanks to the medical professionals of Spain, México and Venezuela who have collaborated with this article.

Please cite this article as: Ríos A. Cirugía taurina en el siglo XXI. De la gloria al desprecio. Cir Esp. 2021;99:482–489.