Transoral Endoscopic Thyroidectomy Vestibular Approach (TOETVA) is a novel technique that allows the thyroid to be approached without visible scars, as it is performed through a natural orifice. It was first described and developed in Asia where due to sociocultural reasons neck scars are considered a stigma. This technique, as we now nowadays, and its preliminary results, were first reported by Angkoon Anuwong in August 2015 at the International Association of Endocrine Surgeons (IAES) world surgery congress held in Bangkok.

Here we present the TOETVA approach, step-by-step, in order it could be safely replicated, aiming also it can be spread within the therapeutic framework of endocrine surgery. However, it is important to remark that, as happens in most of remote approaches, it is only suitable for a small percentage of patients.

La tiroidectomía endoscópica transoral por vía vestibular (TOETVA) es una técnica novedosa que permite abordar el tiroides sin cicatrices visibles, ya que se realiza a través de un orificio natural. Tiene su origen en Asia debido a que, por motivos culturales, una cicatriz en el cuello puede ser considerada un estigma. Esta técnica, tal y como la conocemos ahora y sus resultados preliminares, fueron comunicados por primera vez por Angkoon Anuwong en agosto del 2015 en el congreso mundial de cirugía de la International Association of Endocrine Surgeons (IAES) en Bangkok.

Con el objetivo de difundir el abordaje transoral, lo explicamos paso a paso para que pueda ser reproducido con seguridad y considerado como uno más en el contexto terapéutico de la cirugía endocrina. No obstante, somos conscientes de que, como ocurre con la mayoría de los accesos remotos, solo es aplicable para un pequeño porcentaje de pacientes.

Although thyroid surgery is constantly evolving, its approach has been classically associated with conventional cervicotomy, as described more than 100 years ago and which continues to be the gold standard. In recent years, new minimally invasive, endoscopic and/or robotic approaches with or without gas insufflation (CO2)1 have been implemented.

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) has gained importance in recent years, and thyroidectomy through the oral cavity is one of the most recent additions to the NOTES techniques. Various approaches have been described, some with little success (such as the sublingual route) and others with more success, such as the vestibular route, which we now present.2–7

Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy via the vestibular approach (TOETVA) is a technique that provides the most direct access to the thyroid due to its proximity to the oral cavity, and also bilaterally. It has the added value of being the approach with the best cosmetic results as it does not leave visible scars.8

This approach has been developed primarily in Asia, where, for cultural reasons, cervical scars are considered a stigma.

Transoral surgery as we now know it and its preliminary results were first reported by Angkoon Anuwong at the International Association of Endocrine Surgeons (IAES) World Congress of Surgery in Bangkok in 2015. Since then, various surgeons in Europe and America have adopted this approach trying to spread it and implement it gradually, although at a slower pace because in our society its demand is exclusively due to cosmetic reasons.

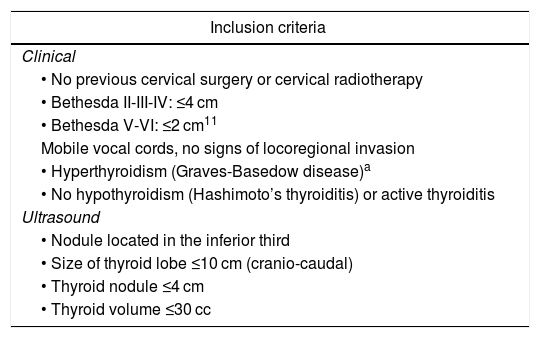

Surgical techniqueIndicationsTransoral surgery requires being very careful and restrictive with the indications, especially in the first few cases. Subsequently, and as the surgeon gains experience, more voluminous lesions and other indications can be included. In any case, it is recommended that, before implementing the transoral approach, the surgeon should have experience in conventional thyroid surgery and be skilled in endoscopic surgery. Table 1 shows the clinical and ultrasound criteria that allow patients to be included or excluded for the transoral approach.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for TOETVA.

| Inclusion criteria |

|---|

| Clinical |

| • No previous cervical surgery or cervical radiotherapy |

| • Bethesda II-III-IV: ≤4 cm |

| • Bethesda V-VI: ≤2 cm11 |

| Mobile vocal cords, no signs of locoregional invasion |

| • Hyperthyroidism (Graves-Basedow disease)a |

| • No hypothyroidism (Hashimoto’s thyroiditis) or active thyroiditis |

| Ultrasound |

| • Nodule located in the inferior third |

| • Size of thyroid lobe ≤10 cm (cranio-caudal) |

| • Thyroid nodule ≤4 cm |

| • Thyroid volume ≤30 cc |

| Exclusion criteria |

|---|

| • Superior pole: |

| Very voluminous |

| Cranial prolongation |

| • Inferior pole: endothoracic extension |

| • Locally advanced thyroid cancer: |

| Suspicion of extrathyroid extension |

| Presence of lateral-cervical lymphadenopathies |

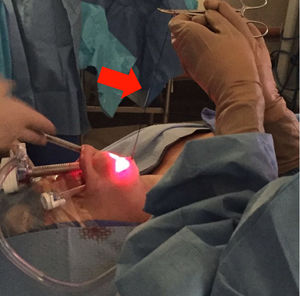

According to the technique described by Anuwong et al,9 the procedure is performed under general anesthesia and nasotracheal or orotracheal intubation indistinctly. The advantage of orotracheal intubation is that it allows the laryngeal nerve to be monitored with conventional orotracheal devices. Typically, the procedure involves the use of a 10-mm 30° scope, 5-mm forceps, and ultrasonic vessel sealing device. Optionally, a 5-mm scope can be used to perform the thyroidectomy, although this requires subsequent replacement with a 10-mm trocar for the extraction of the surgical specimen.

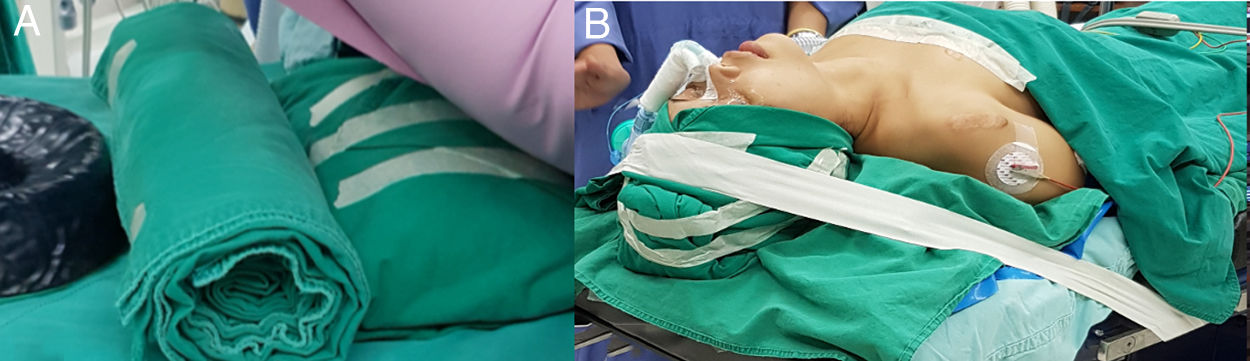

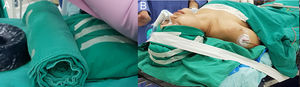

PlacementThe patient is placed in supine position with slight hyperextension while providing support in all segments of the back (shoulders, cervical and occipital regions) (Fig. 1a). It is very important to immobilize the head in this step so as not to lose the field during surgery (Fig. 1b).

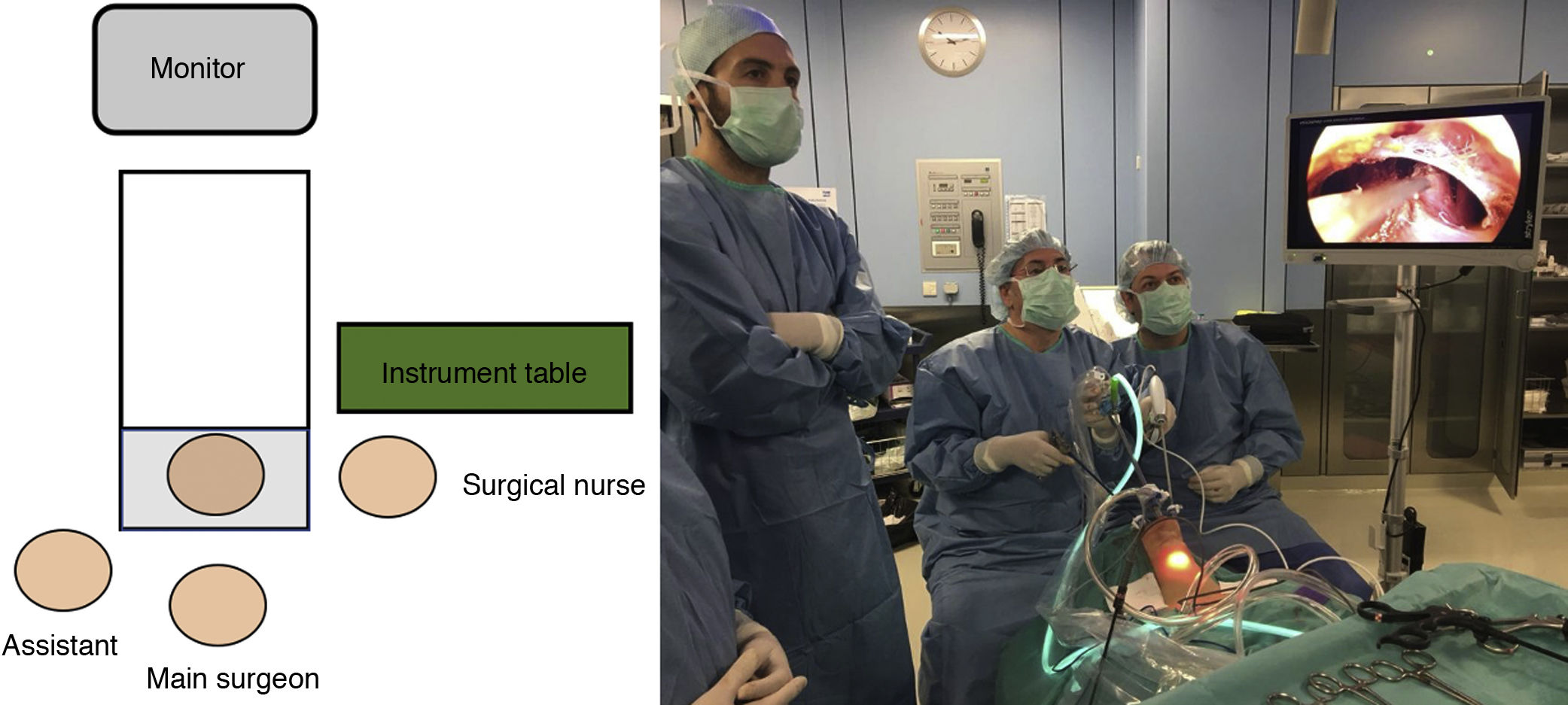

Regarding the position in the surgical field (Fig. 2), the main surgeon is at the head of the patient in front of the screen, the assistant stands next to the surgeon on the side of the thyroid lesion, while the surgical nurse stands on the opposite side.

Asepsis and antibiotic prophylaxisPatients are administered 2 g amoxicillin-clavulanic acid intravenously during induction, 30 min before the incision, and 1 g every 8 h on the first postoperative day. The mouth is disinfected with non-alcoholic chlorhexidine solution, paying special attention to the anterior part of the vestibule.

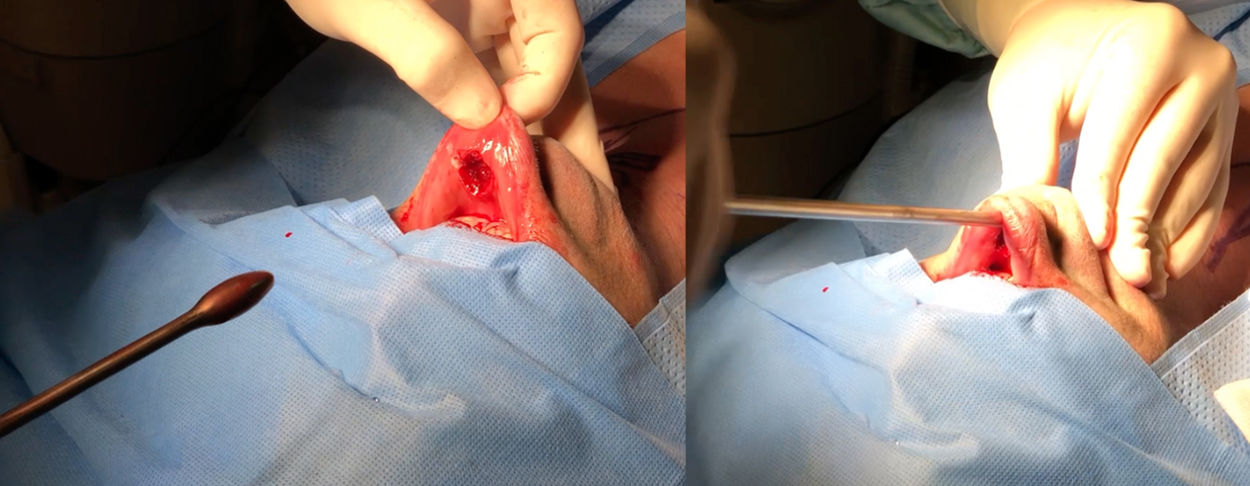

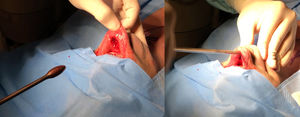

Initial incisions/dissectionFor the 10-mm port, a 2-cm horizontal incision is made in the midline, 0.5−1 cm below the lip and approximately 5 mm above the labial frenulum. This detail is important so that it remains free and does not retract with the suture.

For placement of the two lateral trocars, a vertical incision of approximately 5 mm is made. As a reference, it is important not to exceed the canine teeth laterally or make the incision near the commissure, thereby trying to avoid injuring the main trunk of the mental nerve and not colliding with the marginal branch of the facial nerve (Fig. 3).

Through the incisions, a solution of 1 mg adrenaline diluted in 500 mL of saline is injected into the subplatysmal space with a Veress needle. The limits correspond with the area of the subplatysmal flap that we are going to create, from the tip of the chin to the sternal notch and between the anterior margins of both sternocleidomastoid muscles.

Subsequently, tunneling is performed using Bengolea or Crile forceps in the area of the lower lip until the mandible is reached and, once this point has been passed, the subplatysmal space is dilated with the Anuwong blunt dissector (Fig. 4).

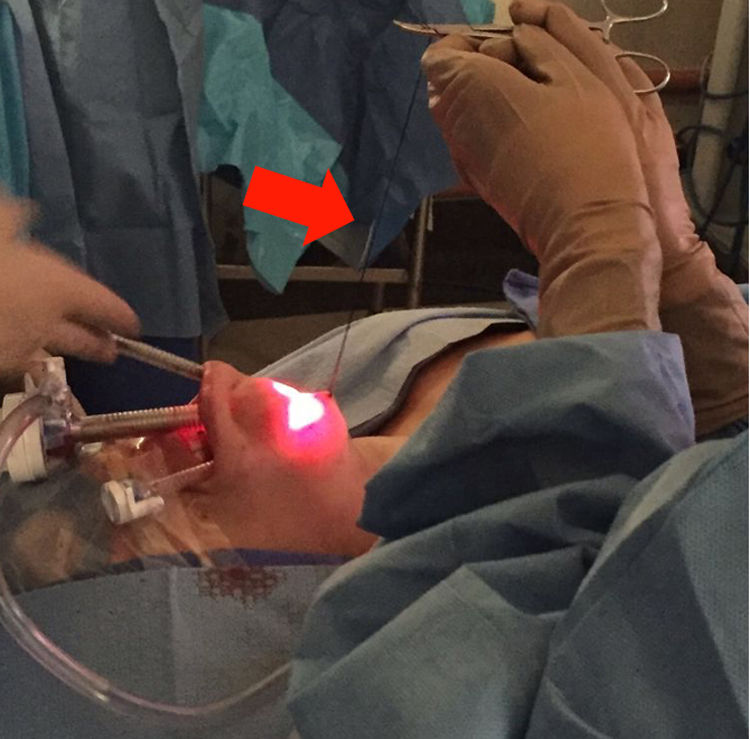

Once the trocars are in place, CO2 is insufflated until reaching a maximum pressure of 6 mmHg, maintaining a flow of 15 L/min. A transcutaneous suture is placed at the level of the cricoid cartilage to be able to tent the flap and achieve a better view of the subplatysmal plane. This expands the field and allows for identification of the anterosuperior margins of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the sternal notch. In long necks, another more caudal suture can be added electively in the midline to improve visibility and increase the space of the surgical field (Fig. 5).

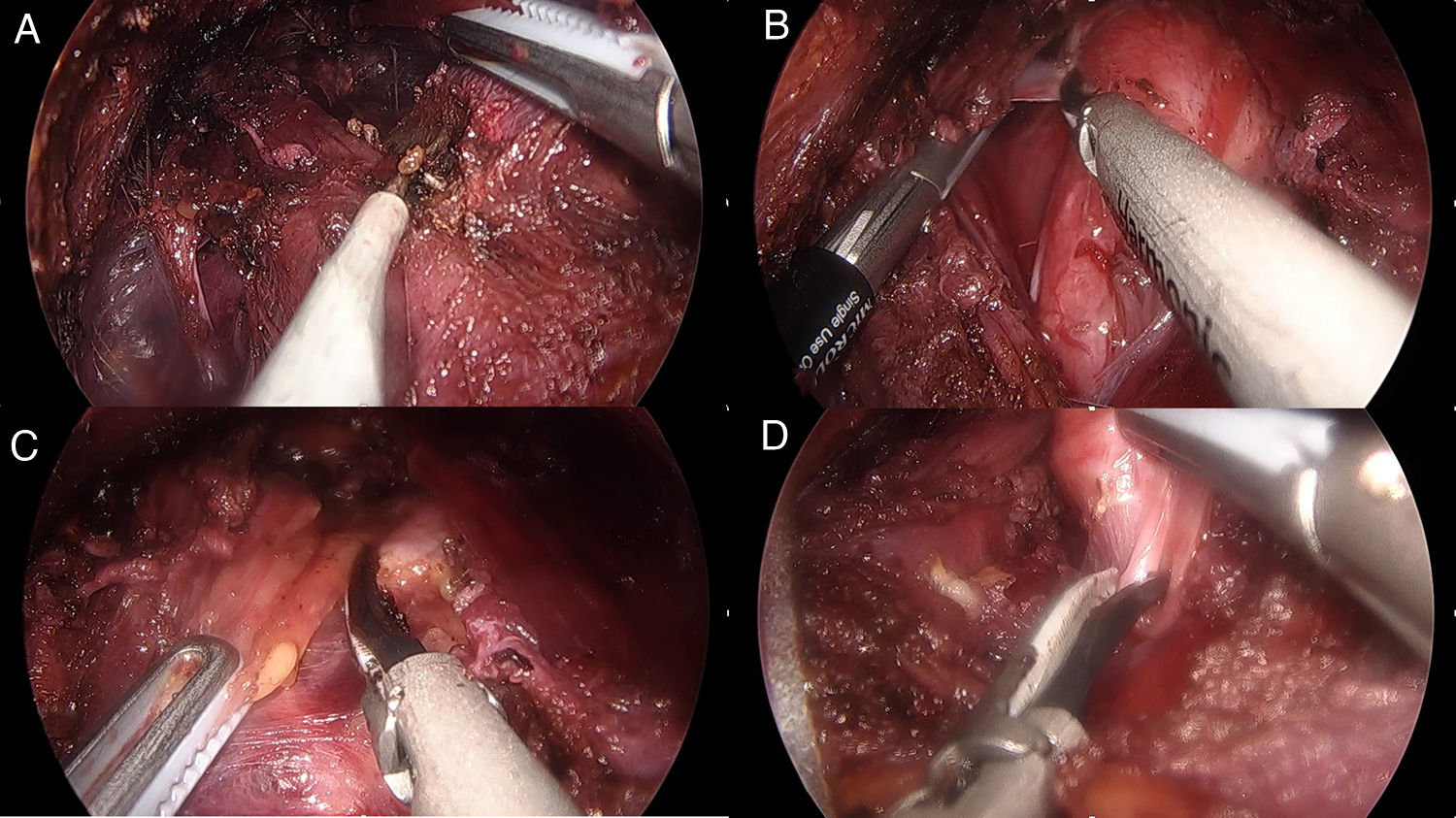

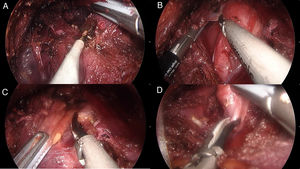

Thyroid dissectionLike in conventional surgery, the prethyroid muscles are separated on the midline (Fig. 6a), then the thyroid lobe is popped up (Fig. 6b) and the isthmus is divided, avoiding contact of the active blade of the harmonic scalpel with the trachea (Fig. 6c).

Contrary to conventional surgery, thyroidectomy is performed in the craniocaudal direction. Initially, the vessels of the upper pole of the thyroid are sealed and divided (Fig. 6d). At this point, we can opt to increase the visual field with a transcutaneous traction suture to laterally retract the prethyroid muscles.

Once the superior pole is released, it is moved caudally and medially to identify the superior parathyroid gland to then locate the recurrent laryngeal nerve that is located medially between the parathyroid gland and the thyroid. The recurrent nerve is dissected craniocaudally in order to perform the thyroidectomy safely with the harmonic scalpel.

It should be noted that the identification of the inferior parathyroid glands is not mandatory. In most cases, they can be easily preserved if the dissection is performed on the thyroid capsule.

ExtractionOnce the thyroidectomy is complete, the surgical specimen is placed in a retrieval bag and extracted through the 10-mm trocar (Fig. 7).

ClosureAfter confirming hemostasis, the thyroid muscles are approximated on the midline using a short (12 mm), absorbable, barbed suture. Subsequently, the subcutaneous plane is lubricated with liquid paraffin to prevent fibrosis and anterior cervical skin retraction. Last of all, the trocar holes are closed with absorbable interrupted sutures (5-mm holes in one plane, and 10-mm holes in 2 planes).

Postoperative managementA submandibular compression bandage is recommended for the first 24 h. Oral tolerance is initiated with a liquid diet on the same day of surgery, progressing in consistency on the first postoperative day. Cold compresses are recommended to reduce inflammation. Subcutaneous emphysema usually resolves within the first 24 h.

DiscussionTransoral thyroid surgery (TOETVA) is a technique that originated in southeast Asian countries and is recently being implemented in Europe and America.

Currently, very few surgeons have adopted this approach in Spain, mainly due to the low demand from our patients, as well as the few cases that can be selected for this approach.

According to the experience gained to date, transoral surgery is shown to be a safe technique, with no significant differences in the rate of complications compared to the open approach, in addition to reporting less subjective sensation of pain.8

Among the different remote-access thyroidectomy techniques, the transoral approach is the only one that does not leave a visible scar.1 Thus, compared to other remote approaches, the main benefit is cosmetic, and patients at high risk of developing keloids or those who are greatly concerned about aesthetics will benefit the most from transoral thyroid surgery.1,10

In the same way as other remote techniques, TOETVA requires longer surgical times than open surgery, which the Anuwong et al. series reported as 100.8 min for TOETVA vs 79.4 min for the open approach.10 However, endoscopic surgery surgical times can be reduced as experience with the technique increases.

Regarding complications, it can be said that “new approaches entail new complications.” TOETVA is associated with the intrinsic complications of thyroidectomy (regardless of the approach) as well as the complications associated with the transoral approach, such as anesthesia of the mental nerve region, trocar bleeding, mobility alterations in the commissure, or fibrosis in the cervical region, all of which have been transient in our experience.

In terms of technical limitations, transoral surgery does not provide access to the lateral compartment, nor is it apt for surgery of large lesions. In patients with cancer, it is recommended that the lesion be intrathyroidal and not exceed 20 mm.11

With this article, we intend to share our experience with transoral surgery, which is a recently implemented technique in our country. Further case series are needed to analyze the results, complications, and cost-effectiveness of this technique in our hospital setting.

Ethical aspectsBefore the transoral surgery, all patients signed a specific authorization allowing photographs of the surgical procedure to be published or used in medical congresses or scientific publications.

In accordance with the Ethics Committee of our hospital, and in compliance with the personal data protection law (Spanish law LOPD 3/2018), we have ensured a high degree of confidentiality.

Contributions of the authorsP. Moreno Llorente designed and drafted the manuscript, while A. García Barrasa, J.M. Francos Martínez and Mireia Pascua Solé have contributed to its composition and correction.

FundingThis study has received no funding of any kind.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Moreno Llorente P, Francos Martínez JM, García Barrasa A, Pascua Solé M. Tiroidectomía endoscópica transoral por vía vestibular: TOETVA. Cir Esp. 2022;100:235–240.