There is currently no effective medical therapy for polycystic liver (PCL). Cyst puncture and sclerotherapy, cyst fenestration, or partial hepatic resections have been used as palliative treatments. Orthotopic liver transplantation (OLT) has become the treatment of choice for terminal PCL, being indicated in patients with limiting symptoms not susceptible to any other medical treatment. It is also difficult to determine the priority on the waiting list using the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD).

MethodsA retrospective analysis of OLT for PCL was conducted in our centre. Inclusion criteria were patients with limiting symptoms, bilateral cysts liver, and insufficient remaining liver. In all cases a deceased donor liver transplantation with piggy-back technique without veno-venous bypass was performed.

ResultsSix patients underwent liver transplantation for PCL between April 1992 and April 2010, one of them being a combined liver–kidney transplantation. The mean intraoperative packed red blood cell transfusion was 3.25L and fresh frozen plasma was 1200cc. Mean operation time was 299min, and 498min in the liver–kidney transplantation. There was no peri-operative mortality. The mean hospital stay was 6.5 days. All the patients are healthy after a mean follow-up of 71 months.

ConclusionOLT offers an excellent overall survival. Results are better when OLT is performed early; thus these patients should receive additional points to be able to use the MELD score as a valid prioritisation system for waiting lists.

A día de hoy no existe una terapia médica eficaz para la poliquistosis hepática (PQH), considerándose tratamientos paliativos la punción quística con escleroterapia, la fenestración o la hepatectomía parcial. El trasplante ortotópico de hígado (TOH) es el tratamiento de elección para la PQH terminal, estando indicado en pacientes con síntomas limitantes no susceptibles de recibir tratamiento médico. Con la aplicación del sistema Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) es difícil determinar la prioridad en la lista de espera.

MétodosAnálisis retrospectivo de los TOH por PQH realizados consecutivamente en nuestro centro. Los criterios de inclusión para TOH en pacientes con síntomas limitantes fueron la presencia de poliquistosis bilateral (Gigot tipo iii) y la hepatomegalia masiva con un hígado remanente insuficiente que imposibilitara una hepatectomía. Se realizó de donante cadáver con técnica piggy-back sin by-pass veno-venoso.

ResultadosEntre abril de 1992 y abril de 2010 se realizaron 6 TOH, uno de ellos combinando trasplante hepatorrenal. La media de transfusión fue 3,25 concentrados de hematíes y 1.200 cc de plasma fresco congelado. El tiempo quirúrgico medio fue 299min y 498min en el hepatorrenal. No hubo mortalidad perioperatoria. La media de hospitalización fue 6,5 días, permaneciendo sanos todos los pacientes tras una media de seguimiento de 71 meses.

ConclusiónEl TOH ofrece una excelente supervivencia global. Los resultados son mejores cuando el trasplante se realiza de una manera precoz, por lo que estos pacientes deberían recibir una puntuación adicional para poder emplear el MELD como una escala válida.

Polycystic liver disease (PCL) can be caused by two different hereditary disorders. One is dominant polycystic autosomal kidney disease resulting from mutations of the PKD1 and PKD2 genes. This is a multisystemic disease with high penetration and variable expression. The majority of patients with this disease also have polycystic liver disease, although it is not normally the main cause of symptoms.1 The other disorder is polycystic liver disease mainly caused by mutations in PRKCSH or in SEC632,3 and with liver cysts in isolation.4 Oestrogen receptors are expressed in the cyst epithelium; therefore symptoms are more frequent in women.5 At the time of diagnosis, it is important to exclude cystoadenoma and cystoadenocarcinoma6 in the differential diagnosis using CT-scan or MRI, although PCL is not associated with an increased risk of malignancy.

Symptoms normally begin in the third or fourth decade of life and are due to cyst growth. Presentation in childhood is therefore rare. Although in the majority of cases liver synthesis capacity is maintained, patients may suffer from dyspnoea, abdominal pain or early satiation, due to the mass effect caused. Malnutrition7–9 presents in fully developed cases. Symptoms are exacerbated when there is compression of the portal vein, the inferior vena cava or extrahepatic bile duct. Major complications of cysts are rupture, infection or bleeding, and are more frequent in cases where haemodialysis is required.10,11 Symptoms develop when mass polycystic disease is already established, when the cyst/parenchyma ratio is normally >1.12

PLD does not normally require treatment. When symptoms appear, the cystic and hepatic volume requires reduction, but there is no effective medical therapy for this. There are several different alternatives depending on the patient and the size, location and number of cysts. The least invasive is guided aspiration using ultrasound or CT scan of the cyst content and subsequent instillation of sclerosing agents to prevent recurrence.13 When this is insufficient, laparoscopic or open cyst fenestrations are required, which are associated with a higher risk of complications such as bleeding, bile leak, ascites or pleural effusion.14–16 Another surgical option is partial liver resection, which has a high morbidity rate and the additional complication of having to design a resection line along the liver already deformed by the cysts, and with the risk of little remaining healthy liver parenchyma.17 Furthermore, hepatectomies create adherences which would cause difficulties for a possible subsequent liver transplant. This surgery should therefore be limited to patients where fenestration is not possible or to those who are not candidates for transplant.18 In either case, these solutions are palliative, not curative.

In recent years, orthotopic liver transplant (OLT) has become the treatment of choice in terminal liver disease due to PCL. It is the only curative option, together with live-donor liver transplant.19,20 On occasion a kidney transplant must be performed at the same time.9,21,22 Since the first OLT for PCL was carried out in 1988,23 morbimortality has decreased thanks to better immune-suppression management and peri-operative care. It is performed on symptomatic patients with a significantly reduced quality of life and who are not susceptible to other medical treatment. Gigot's classification provides the most suitable treatment planning, depending on the characteristics of the cysts: type i: few and large; type ii: multiple and medium in size; type iii: multiple and small and medium in size.24

MethodsA retrospective analysis was made of OLT for PCL performed in our centre. The OLT inclusion criteria for patients with limiting symptoms were bilateral polycystic disease (Gigot type III) and massive hepatomegaly with insufficient remaining liver, making hepatectomy impossible. In all cases a deceased-donor liver transplant using piggy-back technique was performed. Veno-venous by-pass was not used on any of the patients and tailored immunosuppressant therapy was administered, based on tacrolimus, mycophenolate, mofetil and corticoids.

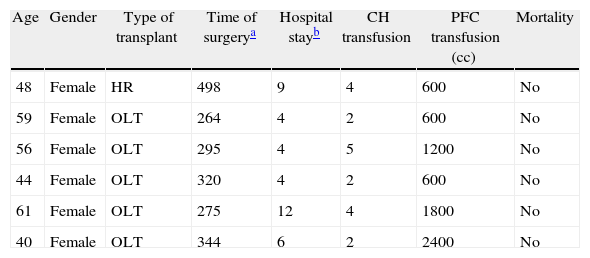

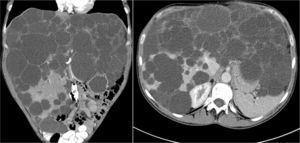

ResultsBetween April 1992 and April 2010, six OLT for PCL were conducted. Demographic data are shown in Table 1. All transplant patients met the inclusion criteria when the OLT was performed and had suffered from progressive symptoms for at least five years, which included: postprandial fullness, early satiation, hepatomegaly, dyspnoea and refractory ascites. A combined liver–kidney transplant was performed on a patient presenting end-stage renal failure without performing an associated nephrectomy during surgery. Fig. 1 shows radiological imaging of one of the transplant patients. The mean transfusion of packed red blood cells was 3.25L (range: 2–5) and of fresh frozen plasma was 1200cc (600–2400). In one case one unit of platelets was also transfused. Mean operation time was 299min (264–344) for OLT and 498 for combined liver–kidney transplantation. The mean weight of the explanted liver was 4112g (2870–5725), although in all cases intraoperative cystic fenestration was performed to facilitate extraction. Fig. 2 shows the macroscopic image of one of the dried livers. There was no operative mortality. Hospital stay was 6.5 (4–12) days, with an average stay in the Intensive Care Unit of 1.5 (1–3) days. No patients needed reoperation. One patient presented stenosis of the suprahepatic vena cava anastomosis, which was successfully treated with vascular endoprosthesis, and a minor ventral hernia which was surgically corrected. Another patient developed a CVM infection, which responded well to treatment with gancyclovir. All patients were healthy after an average follow-up of 71 months (32–246).

Transplant Characteristics.

| Age | Gender | Type of transplant | Time of surgerya | Hospital stayb | CH transfusion | PFC transfusion (cc) | Mortality |

| 48 | Female | HR | 498 | 9 | 4 | 600 | No |

| 59 | Female | OLT | 264 | 4 | 2 | 600 | No |

| 56 | Female | OLT | 295 | 4 | 5 | 1200 | No |

| 44 | Female | OLT | 320 | 4 | 2 | 600 | No |

| 61 | Female | OLT | 275 | 12 | 4 | 1800 | No |

| 40 | Female | OLT | 344 | 6 | 2 | 2400 | No |

CH, red blood cell concentrates; HR, hepatorenal; PFC, frozen fresh plasma; OLT, orthotopic liver transplantation.

PCL is a rare disease with a prevalence of 0.05%–0.13% in autopsy series.25 In Spain, OLT for benign tumours, such as PCL, is less than 0.6%.26 In the European Liver Transplant Registry, PCL represents less than 1%.27 In our centre 354 OLT were conducted during this period, 1.7% of which were for PCL.

Although considered a benign tumour, it can be a major cause of morbidity, and even mortality in the most advanced cases. No appropriate medical treatment exists and invasive solutions such as cystic decompression, aspiration and sclerosis or surgical fenestration only temporarily alleviate symptoms when there are a few large cysts but not so when there are multiple small cysts.17,28,29 There is a controversy regarding the choice of OLT or hepatectomy for this patient group. Hepatectomy for PCL is associated with a higher morbidity rate due to bile leak, postoperative ascites, bacterial infections and deterioration of kidney function. Hepatectomy should be the treatment of choice in patients with no nutritional alterations and with normal or slightly impaired kidney function, in cases where the remaining liver is greater than 30% and taking into consideration the distribution of the cysts and sectoral vascularisation.30,31

OLT has become the treatment of choice in end-stage liver disease and, in the last two decades, has achieved increasingly higher survival rates for both graft and patient, greatly relieving symptoms.20,32–34 The main indication for OLT is the presence of limiting symptoms with massive cystic affectation,35 although applying the Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) system it is difficult to determine priority on the waiting list. At present, many patients develop increased abdominal distension and pain, although malnutrition generally comes later. OLT for PCL is controversial since there is no determining symptom or sign to position the patient on the waiting list.36 Added to this is the particular technical difficulty of surgery for PCL, due to the large size of the liver, previous invasive procedures and the displacement of vascular structures and neighbouring organs. It is also associated with greater blood loss and consequent added morbidity.37

All our surgical interventions were performed preserving the recipient's inferior vena cava (piggy-back) and without veno-venous by-pass. Cystic aspiration and fenestration were required during surgery so that the vascular structures could be better seen and to facilitate hepatic mobilisation, with no incidence of perforation of adjacent organs. Hepatectomy has become a major surgical challenge and controversy exists on how it should be performed. Some authors propose partial hepatectomy, arguing its increased safety,38 whilst others (including our group) believe this could involve a greater risk of haemorrhage.39 In order to improve results and patient survival, early OLT is increasingly advocated (particularly in women), prior to other invasive interventions which technically hamper subsequent OLT.

Patients with PCL should be given priority on the waiting list, since results are clearly worse when OLT is delayed and malnutrition and severe compressive symptoms are present.18,40 In our centre, these patients have been prioritised and given additional points when they are included on the list, since PCL is considered an exception in the strict application of the MELD system.41

ConclusionOLT is the treatment of choice for end-stage PCL, with an excellent overall survival rate, higher than that of OLT for other reasons. Results are better when OLT is performed early and therefore these patients should receive additional points in order to use the MELD score as a valid prioritisation system for waiting lists.

Conflict of InterestThe authors state there is no conflict of interest.

Please cite this article as: Arredondo J, Rotellar F, Herrero I, Pedano N, Martí P, Zozaya G, et al. Trasplante ortotópico de hígado en la poliquistosis hepática. Cir Esp. 2013;91:659–663.

Part of the information from this manuscript was previously presented at the XXIII Congress of the Spanish Liver Transplantation Society held in Bilbao in October 2011.