Metabolic syndrome is a pathological entity associated with a high risk of cardiovascular disease. Data regarding the frequency of this syndrome, lipid profile, and atherogenic index of plasma in patients with radiographic axial spondyloarthritis are scarce.

We aim to determine the prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with spondyloarthritis. We also aim to determine discriminative values of atherogenic indexes between patients with and without metabolic syndrome.

MethodsWe conducted a cross-sectional study including 51 patients meeting the ASAS 2009 criteria for radiographic axial spondyloarthritis. We measured the following parameters: triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoproteins (HDLc), low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc), and total cholesterol (TC). We calculated TC/HDLc, TG/HDLc, LDLc/HDLc ratios, and atherogenic index of plasma (LogTG/HDLc).

ResultsMetabolic syndrome was noted in 33% of cases. Patients with active disease had a higher body mass index (26.89±5.88 versus 23.63±4.47kg/m2, p=0.03), higher TG (1.41±0.64 versus 0.89±0.5mmol/L, p=0.05) and a lower HDLc level (1±0.28 versus 1.31±0.22mmol/L, p=0.01). However, the LogTG/HDLc and TG/HDLc were higher in patients under TNFα inhibitors. The ability of the TG/HDLc ratio and LogTG/HDLc to distinguish patients with or without metabolic syndrome were good at cut-offs of 1.33 and 0.22, respectively (specificity: 91.2% and sensitivity 70.6% for both ratios).

ConclusionOur study showed that metabolic syndrome is frequent in patients with axial spondyloarthritis. Atherogenic indexes can be used for predicting metabolic syndrome in these patients.

El síndrome metabólico es una entidad patológica asociada a un alto riesgo de enfermedad cardiovascular. Los datos sobre la frecuencia de este síndrome, el perfil lipídico y el índice aterogénico del plasma en pacientes con espondiloartritis axial radiográfica son escasos.

Nuestro objetivo es determinar la prevalencia del síndrome metabólico en pacientes con espondiloartritis. También pretendemos determinar valores discriminativos de índices aterogénicos entre pacientes con y sin síndrome metabólico.

MétodosRealizamos un estudio transversal que incluyó a 51 pacientes que cumplían los criterios ASAS 2009 para espondiloartritis axial radiográfica. Medimos los siguientes parámetros: triglicéridos (TG), lipoproteínas de alta densidad (HDLc), colesterol de lipoproteínas de baja densidad (LDLc) y colesterol total (CT). Calculamos las relaciones CT/HDLc, TG/HDLc, LDLc/HDLc y el índice aterogénico del plasma (LogTG/HDLc).

ResultadosEl síndrome metabólico se observó en el 33% de los casos. Los pacientes con enfermedad activa tenían un índice de masa corporal más alto (26,89±5,88 versus 23,63±4,47kg/m2; p=0,03), TG más altos (1,41±0,64 versus 0,89±0,5 mmol/L; p=0,05) y un nivel de HDLc más bajo (1±0,28 versus 1,31±0,22mmol/L; p=0,01). Sin embargo, el LogTG/HDLc y TG/HDLc fueron mayores en pacientes bajo inhibidores del TNFα. La capacidad de la relación TG/HDLc y LogTG/HDLc para distinguir pacientes con o sin síndrome metabólico fue buena en puntos de corte de 1,33 y 0,22, respectivamente (especificidad: 91,2% y sensibilidad: 70,6% para ambas relaciones).

ConclusiónNuestro estudio mostró que el síndrome metabólico es frecuente en pacientes con espondiloartritis axial. Los índices aterogénicos se pueden utilizar para predecir el síndrome metabólico en estos pacientes.

The metabolic syndrome (MetS) is a cluster of clinical and biological abnormalities, including disturbances in lipid and carbohydrate metabolism associated with a pro-inflammatory disorder.1,2

The MetS predisposes to atherosclerosis and its progression.1 It is associated with a high risk of morbidity and mortality due to coronary artery and cerebrovascular diseases.

Despite the lack of consensus regarding this syndrome definition, the 2009 international Diabetes Federation (IDF) definition remains the most harmonious.3 Indeed, the cut-off values for waist circumference in this definition are according to ethnicity.

The risk of atherosclerosis may also be assessed by the atherogenic indexes, including total cholesterol (TC)/high-density lipoproteins (HDLc), Triglyceride (TG)/HDLc, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDLc)/HDLc ratios, and atherogenic index of plasma (LogTG/HDLc).4,5

Several studies showed that MetS is frequent in patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatic diseases.6,7

However, data regarding the frequency of this syndrome in radiographic axial spondyloarthritis (SpA) are scarce. SpA is a rheumatic disease characterized by enthesal and systemic inflammation leading to osteoformation and ankylosis.8 The risk of cardiovascular diseases and MetS seems higher in these patients.9,10 Therefore, the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommends screening cardiovascular risk factors at least once every five years in SpA patients.11

Besides, the effect of tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors (TNFi) on MetS in patients with SpA is not well known.

We aim to determine the prevalence of MetS in patients with SpA and compare the lipid profile depending on the disease activity. We also aim to determine discriminative values of atherogenic indexes between patients with and without MetS.

MethodsStudy designWe conducted a cross-sectional study over a period of 2 years [May 2018–May 2020], including 51 consecutive patients followed for spondyloarthritis.

Inclusion criteriaWe included patients with axial radiographic spondyloarthritis diagnosed according to Assessment of SpondyloArthritis international Society (ASAS) 2009 criteria.13

The diagnosis was made based on the presence of radiographic sacroiliitis associated with at least one of the following items: inflammatory back pain, arthritis, enthesitis, uveitis, dactylitis, psoriasis, good response to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, family history of SpA, HLB-B27, or elevated C-reactive protein (CRP).

Non-inclusion criteriaWe did not include patients with chronic inflammatory bowel disease, cirrhosis, liver failure, diseases causing malabsorption and progressive neoplasms, patients with familial dyslipidemia,14 and secondary dyslipidemia.15

We did not also include patients under treatments that may influence the parameters of the MetS such as long-term corticosteroids, non-cardio-selective beta-blockers, retinoids, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, estrogens, thiazide diuretics, and antiretrovirals.

We excluded patients with pathology that may overestimate waist circumference measurements such as ascites, white line or umbilical hernia, eventrations, and visceromegaly.

Clinical assessmentWe collected demographic and clinical data, including age, gender, age at disease onset, disease duration, and therapeutic management. The Spondylitis Disease Activity Index (BASDAI)16 and Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score (ASDASCRP)17 were used to assess disease activity. The SpA is considered active when the BASDAI score is higher than 4. Using the ASDASCRP, the disease is active when this score is higher than 2.1.

The waist circumference (WC) was measured using a tape measure placed horizontally, halfway between the last rib and the iliac crest.

The body mass index (BMI) was calculated from the ratio of weight to the square of the height (kg/m2) and was interpreted according to the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO).18 Blood pressure was measured using the standard procedure which is the auscultation method using a mercury sphygmomanometer.

Biological parametersWe measured the following parameters after 12h of fasting: fasting glucose (FG), TG, HDLc, LDLc,19 TC, CRP, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

We calculated the atherogenic indexes,4 including TC/HDLc, TG/HDLc, LDLc/HDLc, and the atherogenic index of plasma (AIP) Log (TG/HDLc).

Laboratory analysis was carried out by D*C 700 Au Beckman Coulter. Blood samples were assessed using immune-inhibition for HDLc, glycerol phosphate oxidase-p-aminophenazone (GPO-PAP) methods for TG, cholesterol oxidase phenol 4-aminoantipyrine peroxidase (CHOD-PAP) method (CHOD-PAP) for TC and LDLc, and immunoturbidmetry method for CRP.

Diagnosis of metabolic syndromeAccording to 2009 IDF criteria,3 MetS is present if three or more of the following criteria are met: abdominal obesity (WC higher than 94cm in men and 80cm in women), TG>1.5g/L (1.7mmol/L), HDLc less than 0.4g/L (1.03mmol/L) in men and 0.5g/L (1.26mmol/L) in women or dyslipidemia under treatment, systolic blood pressure (PAS)≥130mmHg or diastolic blood pressure (DBP)≥85mmHg or hypertension under treatment, fasting glucose≥1g/L (or 5.6mmol/L) or type 2 diabetes.

StatisticsWe performed statistical analysis using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences. Continuous variables were presented as the mean±standard deviation (SD). We compared categorical variables between groups using the student's t-test. Continuous variables were compared using t-tests. Correlations were tested using the Pearson correlation test and quantified by reporting the Pearson correlation coefficient. The significance level was set at a p-value<0.05. Binary Logistic Regression was performed to identify predictors of MetS. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were evaluated for each atherogenic index using the existence of MetS as the gold standard. The closer the area under the curve (AUC) to 1, the more performant the ratio is discriminating patients with MetS.

Ethical considerationThis study was approved by the ethics committee of the Hospital. Consent was signed by patients after informing them of the aims of the study and the data collection methods.

ResultsPatients and metabolic syndrome characteristicsClinical and epidemiological characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Clinical and biological data of patients.

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Age (years) | 44.92±12.37 |

| Weight (kg) | 73.09±13.63 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 25.13±5.33 |

| Smokers (%) | 63 |

| High blood pressure (%) | 22 |

| Diabetes (%) | 17 |

| Age of onset of SpA (years) | 37.5±11.9 |

| Duration of the disease (months) | 125.7±103.1 |

| Phenotype of the axial radiographic SpA (n(%)) | 36 (71) |

| SpA PsA (n(%)) | 15 (29) |

| ASDASCRP | 2.99±1.24 |

| BASDAI | 3.74±2.04 |

| Patients treated with TNFi (%) | 35 |

| Inflammatory parameters | |

| ESR (mm) | 40.3±32 |

| CRP (mg/L) | 35.4±52.6 |

| Metabolic syndrome parameters | |

| FG (mmol/L) | 5.64±1.37 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 1.33±0.65 |

| HDLc (mmol/L) | 1.06±0.289 |

| WC (cm) | 87±13 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 125.29±12.86 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 77.05±7.82 |

| Atherogenic indexes | |

| TC/HDLc ratio | 4.3±1.24 |

| TG/HDLc ratio | 1.31±0.75 |

| LDLc/HDLc ratio | 2.72±1.03 |

| Log TG/HDLc (AIP) | 0.07±0.23 |

Values are expressed as mean±SD (standard deviation), SpA: spondyloarthritis, PsA: psoriatic arthritis, BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Index, ASDAS: Ankylosing Spondylitis Disease Activity Score, TNFi: TNF inhibitor, BMI: body mass index, ESR: erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP: C-reactive protein, TC: total cholesterol, TG: triglycerides, HDLc: high density lipoprotein cholesterol, LDLc: low density lipoprotein cholesterol, WC: waist circumference, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, AIP: atherogenic index of plasma.

There were 43 men. A BMI≥25kg/m2 was noted in 47% of cases.

Psoriasis was found in 15 cases.

Active disease (BASDAI≥4) was noted in 44% of cases (n=22). Using ASDASCRP, 92% of patients had active disease (n=47).

MetS parameters, atherogenic indexes, and AIP are summarized in Table 1.

The MetS was found in 33% of cases (n=17).

The frequency of MetS was higher in patients with psoriasis (54% (8/15) versus 26% (9/36), p=0.05).

WC was 103±17.05cm [80–135] in women and 85.05±11cm [65–109] in men. Abdominal fat distribution was noted in 35% (n=18) of cases: 7 women and 11 men.

The SBP was higher than 130mmHg in 47% of cases (n=24). Nine patients (17.6%) had DBP greater than 85mmhg. Twenty-four patients had SBP higher than 130mmHg or DBP higher than 85mmHg. FG≥5.6mmol/L was found in 37% of cases (n=19). Four patients had type 2 diabetes (8%). Eleven patients (22%) had hypertriglyceridemia. Low HDLc levels were observed in 57% of cases (n=29).

Relation between metabolic syndrome and SpA characteristicsMetS was more common in women than in men (86% versus 26%; p=0.006).

There was no significant difference between patients with or without MetS regarding the age (48.75±12.44 versus 42.42±4.69 years; p=0.08 and the disease activity (ASDASCRP: 3.56±1.66 vs 3.05±1.92, p=0.35 and BASDAI: 4.27±1.95 vs 3.54±2.05, p=0.23).

The comparison of parameters of MetS between patients with or without active disease is shown in Table 2. The BMI and TG were higher in patients with high and very high disease than those in low disease activity and in remission.

Metabolic syndrome parameters according to disease activity using the ASDASCRP score.

| ASDAS<2.1(N=9) | ASDAS≥2.1(N=42) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.63±4.47 | 26.89±5.88 | 0.03 |

| WC (cm) | 88.85±15.88 | 87.13±13.77 | 0.765 |

| SBP (mmHg) | 121.42±12.14 | 125.9±12.99 | 0.397 |

| DBP (mmHg) | 79.28±7.31 | 76.7±7.91 | 0.423 |

| FG (mmol/L) | 5.22±0.48 | 5.77±1.45 | 0.33 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.89±0.5 | 1.41±0.64 | 0.05 |

| HDLc (mmol/L) | 1.31±0.22 | 1±0.28 | 0.01 |

All values are represented as mean±standard deviation, BMI: body mass index, WC: waist circumference, SBP: systolic blood pressure, DBP: diastolic blood pressure, FG: fasting glucose, TG: triglycerides, HDLc: high density lipoprotein cholesterol, p: level of significance.

In bold: significant p value (p < 0.05).

The MetS was found in 7 patients treated with TNFi (p=0.544). Patients treated with TNFi had a higher TG/HDLc ratio (1.32±0.57 versus 1.029±0.99, p=0.023).

As shown in Table 3, male sex was a protective factor of MetS with p=0.05 and an odds ratio of 0.044.

Binary logistic regression table studying risk factors for metabolic syndrome in spondyloarthritis.

| Odds ratio | p | Confidence interval 95% | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 1.065 | 0.168 | 0.977–1.127 |

| Male sex | 0.044 | 0.05 | 0.030–0.881 |

| Duration of the disease (months) | 0.993 | 0.224 | 0.982–1.001 |

| Smoking | 0.347 | 0.396 | 0.024–2.640 |

| ASDASCRP≥2.1 | 0.077 | 0.138 | 0.040–2.650 |

| BASDAI≥4 | 0.326 | 0.206 | 0.561–13.08 |

ASDAS: ankylosing spondylitis disease activity score, CRP: C-reactive protein, BASDAI: Bath Ankylosing spondylitis disease activity index, p: significance level.

In bold: significant p value (p < 0.05).

Correlations were found between disease activity and both BMI (r=0.284, p<0.01) and TG (r=0.374, p<0.01). Nevertheless, no correlations were found between inflammatory biomarkers and MetS parameters.

Atherogenic indexes and metabolic syndromeThe atherogenic indexes and AIP were higher in patients with MetS (TC/HDLc: 5.06±1.44 versus 3.92±0.92, p: 0.001; TG/HDLc: 1.94±0.86 versus 1±0.41, p<0.001; LDLc/HDLc: 3.3±1.18 versus 2.44±0.79, p: 0.003; Log (TG/HDLc): 0.24±0.23 versus – 0.04±019, p<0.001).

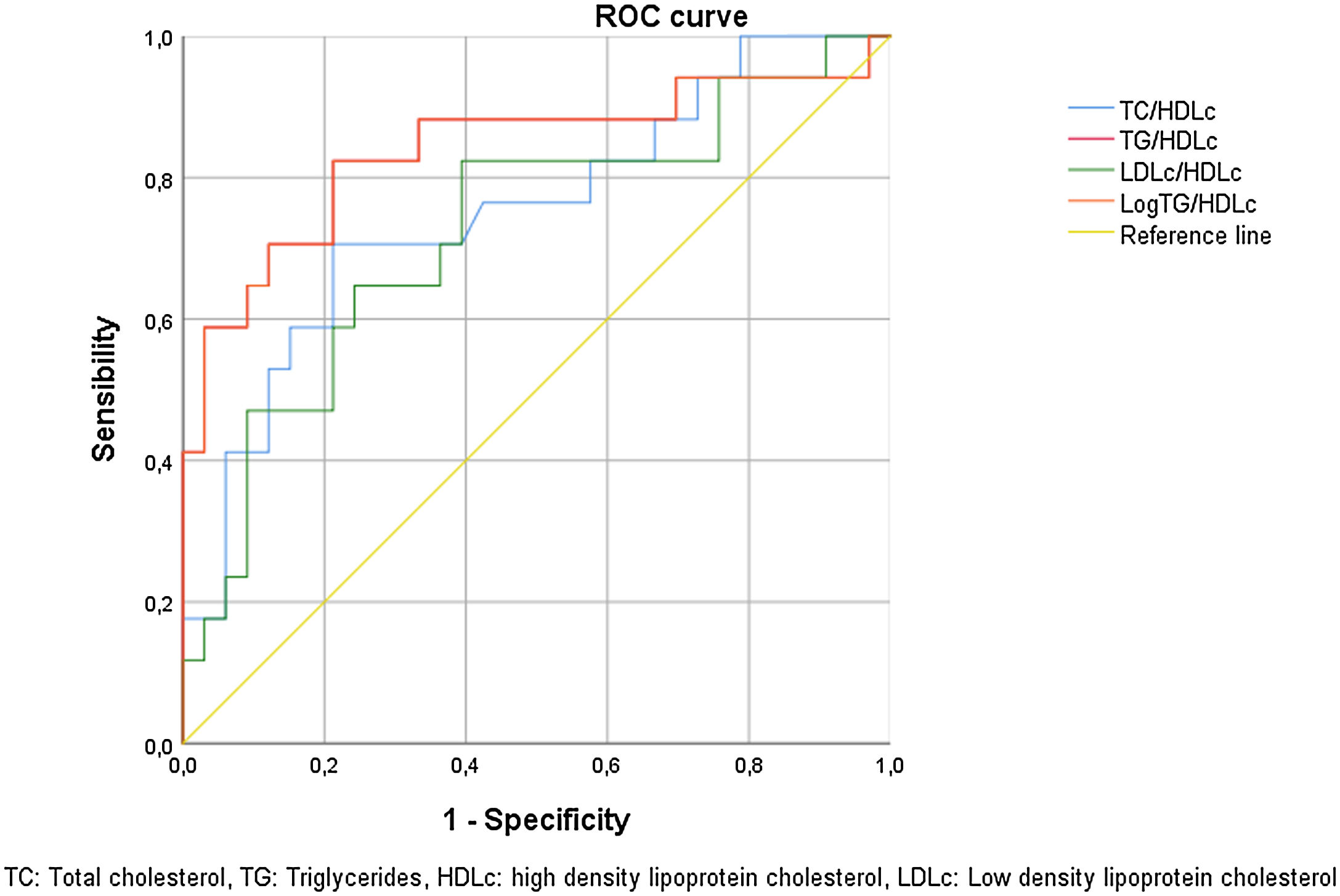

As shown in Fig. 1, ROC curve analysis for atherogenic indexes demonstrated that TG/HDLc ratio and AIP can discriminate patients with MetS with a cut-off of 1.33 and 0.22, respectively (AUC: 0.834, sensitivity: 70.6%, specificity: 91.2% for both ratios).

The LDLc/HDLc ratio and TC/HDLc ratio were able to discriminate patients with MetS with a cut-off of 2.46 (AUC: 0.72, sensitivity: 82.4%, and specificity: 60.6%) and 4.44 (AUC: 0.75, sensitivity: 70.6%, and specificity: 78.8%), respectively.

DiscussionIn our study, we attempted to determine the frequency of MetS in patients with SpA. The MetS was noted in 33% of patients. This frequency seemed to be higher than in the general population in our country, estimated at 13.4%.20

Papadakis et al. showed that MetS was significantly more frequent in patients with SpA than in healthy controls (34.9% versus 19%; p<0.05).12

Similarly, several studies demonstrated that MetS was frequent in rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic lupus erythematosus, occurring in 8.2–52.8%21–24 and 35.7–46.6%,25,26 respectively.

Mok et al. included 930 patients with chronic inflammatory rheumatism (122 SpA, 109 Psoriatic arthritis (PsA), and 699 RA), the MetS was found in 38%, 20%, and 11% of patients with PsA, RA, and SpA (p<0.001), respectively.7

Our study showed that MetS was more frequent in women (86% versus 26%; p=0.006). However, Pehlevan et al. didn’t find an association between gender and MetS.27

In our study, the age did not differ between patients with or without MetS. This result was in line with earlier studies.27

Disease duration did not differ between patients with or without MetS.28

Besides, no difference in disease activity between patients with or without MetS. These results were reported by several studies.27,29,30 Nevertheless, hypertriglyceridemia and low HDLc levels were higher in patients with active disease.

Petcharat et al. found that MetS was associated with structural damage assessed by syndesmophytes’ number in SpA and PsA.31 This association was not evaluated in our study.

TNFα, a pro-inflammatory cytokine excessively secreted in patients with SpA, increases the TG levels via the inhibition of adipocyte lipoprotein lipase activity and the stimulation of liver lipogenesis.32 This finding suggests that disease remission may control inflammation and improve TG and HDLc levels.

Even if TNFα is involved in lipid metabolism, insulin resistance, and obesity,27 the effect of TNFi on MetS remains controversial. Pishgahi et al. showed that SpA patients with MetS had higher serum TNFα, interleukin 1, and Th17 cells levels.33 However, Costa et al. demonstrated that TNFi improved MetS parameters.34 Indeed, the authors found that 12 months TNFi treatment was able to decrease metabolic markers such as myeloperoxidase, adiponectin, and chemerin levels in RA and SpA patients.35 The treatment with TNFi did not appear to decrease the frequency of MetS.7 Likewise, in our study, the prevalence of MetS did not differ between patients with or without TNFi. Other studies showed that the prevalence of MetS was higher in patients with TNFi compared to those with conventional treatment.12,27 The effectiveness of this treatment seemed to be lower in patients with MetS.36

The effect of TNFi on atherogenic indexes is not yet clear. In our study, patients treated with TNFi had a higher TG/HDLc ratio and AIP. However, Steiner et al. showed that TNFi improved AIP in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.37 In a study including 238 SpA patients, no association was found between the use of biological treatment and AIP.38

Tournadre et al. showed that interleukin 6 inhibitors led to a significant weight gain at the expense of skeletal muscle mass in RA patients. This finding suggests that this treatment may prevent cachexia,39 which seems to aggravate MetS.40

Psoriasis was associated with a high prevalence of MetS.41 Indeed, abdominal obesity, which is more frequent in patients with this disease, contributes to the occurrence of MetS by increasing insulin resistance,41 lipotoxicity,42 and secretion of adipokines (leptin, resistin, visfatin, and adiponectin).42

Moreover, skin lesion of psoriatic patients produces inflammatory cytokines and may explain the high frequency of MetS in these patients.7 In our study, the frequency of MetS was higher in patients with psoriasis.

Our study showed that patients with higher BMI had the highest disease activity. This result was reported by Klingberg et al.42 These findings suggest that applying nutritional therapeutic education may improve disease activity in SpA patients. Indeed, in patients with psoriatic arthritis, weight loss after a diet or bariatric surgery led to clinical improvement, highlighting the important role of adipose tissue on the disease activity.42,43

The lipid balance alone helps to stratify cardiovascular risk. TG/HDLc, TC/HDLc, LDLc/HDLc ratios, and AIP are more reliable to screen cardiovascular risk.44,45 AIP is considered a predictor of obesity, high blood pressure, and diabetes.46 Atherogenic ratios (TC/HDLc, TG/HDLc, LDLc/HDLc) and AIP were significantly higher in patients with MetS. These findings were consistent with those of Maia et al. who found that AIP was higher in patients with MetS (0.68±0.46 versus 0.34±0.24, p=0.002).27

The TG/HDLc ratio and the AIP were able to distinguish patients with MetS with cut-offs of 1.33 and 0.22, respectively (specificity: 91.2% and sensitivity: 70.6%).

A significant association was found between MetS and AIP. This association remains significant using multivariate regression.47 Similarly, the ability of the LDLc/HDLc and TC/HDLc ratios to distinguish patients with MetS was acceptable with a threshold of 2.46 and 4.44, respectively.

These results suggested that atherogenic indexes can be useful to identify patients with MetS.

This ratio is easy to calculate and would be accurate to discriminate patients with MetS.

There are limitations to our study, notably the small number of patients. Prospective cohort studies with longitudinal follow-ups are needed to confirm our results.

ConclusionOur study showed that metabolic syndrome is frequent in patients with SpA. The atherogenic indexes seemed to be useful to identify patients with metabolic syndrome.

BMI was higher in patients with high disease activity suggesting that nutritional therapeutic education is necessary and may improve disease activity.

Hypertriglyceridemia and low HDLc levels were also associated with high disease activity highlighting that achieving remission may improve triglyceridemia and HDLc levels which are two parameters of metabolic syndrome.

Authors’ statement- -

Khaoula Ben Ali and Lobna Kharrat have drafted the work.

- -

Maroua Slouma has substantively revised the work.

- -

Chedia Zouari and Haroun Ouertani have made substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data.

- -

Imen Gharsallah has made substantial contributions to the design and the conception of the work.

The authors declare that they have no funding for this study.

Conflict of interestNone.

None.