To determine the extent to which low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) therapeutic targets are achieved in patients with high and very high vascular risk treated in lipid units, and the reasons why these targets are not met.

Patients and methodObservational and retrospective multi-centre study. Patients over the age of 18 with high or very high vascular risk according to the criteria set forth by the 2012 European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention who were consecutively referred to lipid units between January and June 2012 and with follow-up two years after the first visit were included.

Results243 patients from 16 lipid units were enrolled. The mean age was 52.2 years (SD 13.7) and 62.6% of the patients were male. 40.3% were classified as very high risk. At the first visit, 86.8% were on lipid-lowering treatment (25.1% on combination therapy), which rose to 95.0% at the second visit (47.3% on combination therapy) (p<0.001). A total of 28% (95% CI: 22.4–34.1) achieved the therapeutic target. In terms of the reasons why therapeutic targets were not met, 24.6% of failures were attributed to the medication (10.3% maximum tolerated dose and 10.9% due to the onset of side effects), 43.4% were attributed to the doctor (19.4% due to clinical inertia, 13.7% due to having deemed the goal to have been achieved) and 46.9% were attributed to the patient, primarily non-adherence to treatment (31.4%).

ConclusionsLDL-C therapeutic targets were achieved in around one third of patients. Patient non-adherence, followed by clinical inertia, are the primary causes that could explain these results.

Determinar el grado de consecución del objetivo terapéutico del colesterol de las lipoproteínas de baja densidad (cLDL) en pacientes de alto y muy alto riesgo vascular atendidos en las unidades de lípidos, así como las causas de no consecución.

Pacientes y métodoEstudio observacional retrospectivo multicéntrico. Se incluyó a los pacientes mayores de 18 años con alto o muy alto riesgo vascular, según los criterios de la Guía europea de prevención cardiovascular de 2012, remitidos de forma consecutiva a las unidades de lípidos entre enero y junio del 2012 y con seguimiento a los 2 años de la primera visita.

ResultadosSe incluyó a 243 pacientes procedentes de 16 unidades de lípidos. La edad media fue de 52,2 años (DE 13,7) con un 62,6% de varones. Un 40,3% eran de muy alto riesgo. En la primera visita seguían tratamiento hipolipidemiante el 86,8% (en combinación 25,1%) y en la segunda visita el 95,0% (en combinación 47,3%) (p<0,001). El 28% (IC del 95%: 22,4-34,1) alcanzó el objetivo terapéutico. Sobre las causas de no consecución, el 24,6% de ellas estaban relacionadas con el medicamento (10,3% máxima dosis tolerada y 10,9% por aparición de efectos adversos), el 43,4% con el médico (19,4% por inercia, 13,7% por considerar que ya ha llegado al objetivo) y con el paciente el 46,9%, destacando el incumplimiento terapéutico (31,4%).

ConclusionesSe consiguieron los objetivos de cLDL en cerca de un tercio de los pacientes. La baja adherencia del paciente, seguida de la inercia médica, son las causas más frecuentes que pueden explicar estos resultados.

Lipid metabolism disorders are one of the primary causes of vascular risk.1 Reducing low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) concentrations by 1mmol/l (38.8mg/dl) results in a 22% fall in the relative risk of presenting a severe cardiovascular (CV) event.2

It is important for patients with dyslipidaemia, and particularly patients at high or very high risk, to achieve the therapeutic targets recommended by the CV prevention clinical practice guidelines (CPGs).1 Studies conducted in Europe3–5 and in Spain6–9 have revealed the low frequency with which these LDL-C treatment goals are achieved. The EDICONDIS-ULISEA study10 estimated that 44.7% of dyslipidaemic patients treated at the Lipid and Vascular Risk Units of the Spanish Arteriosclerosis Society (Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis, SEA) achieved their LDL-C therapeutic target as defined by the 2007 European guidelines on CV disease prevention.11 However, these results fell to below 20%6–10 in patients at high or very high risk when the criteria of the most recent European guidelines were applied.12

The causes that could explain inadequate LDL-C control have been attributed to the organisation of the health system, to doctors and to the patients themselves.13 One of the causes attributed to doctors is clinical inertia,13–16 which is defined as treatment not being initiated or intensified despite being indicated in the CPGs.14

Lipid and vascular risk units are clinics run by specialists and experts in the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidaemia.17 Patients who attend such clinics are referred from primary care or from other specialties, such as cardiology, neurology and vascular surgery.18 The aim of this study was to determine the percentage of patients who achieved their LDL-C therapeutic target, as well as to identify the reasons for failing to achieve this goal in patients with high and very high vascular risk treated by lipid and vascular risk units in actual clinical practice.

Patients and methodsDesignObservational, retrospective and longitudinal multicentre study. The study consecutively enrolled patients over the age of 18 who were referred for a first visit to the lipid and vascular risk units of the Network of Lipid and Arteriosclerosis Units of Catalonia (Xarxa d’Unitats de Lípids i Arteriosclerosi de Catalunya) for dyslipidaemia and high or very high CV risk according to the 2012 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice12 between January and June 2012, with follow-up two years after the first visit. Patients with uncontrolled dyslipidaemia secondary to their underlying disorder were excluded.

The study was approved by the central Independent Ethics Committee.

Information from two appointments at the unit was collected from the medical records: the first or baseline visit, conducted at the unit between January and June 2012, and the second follow-up visit conducted two years later. For patients who did not undergo two-year follow-up, the information was obtained from the last recorded visit to the unit at which the applicable data to complete the record were available. The data were collected between December 2014 and December 2015.

Age, gender, anthropometric characteristics (weight, height, body mass index, waist circumference), comorbidity, CV risk factors, type of dyslipidaemia and vascular risk according to the SCORE model were recorded.12 Patients who had given up smoking for six months or more were deemed to be former smokers. Alcohol consumption was stratified as low-medium (<30g/day for women; <40g/day for men), high (≥30g/day for women; ≥40g/day for men) and non-drinker.

The cholesterol-lowering therapy strategy was classified as per the criteria proposed by Masana et al.19 at the following LDL-C reduction intervals: low (LDL-C reduction <30%), moderate (LDL-C reduction 30–49%), high (LDL-C reduction 50–60%) and very high (LDL-C reduction >60%). Patients treated in monotherapy with ion-exchange resins at any dose or fibrates were classified as low.

Data pertaining to lipid profile, blood glucose, creatinine, creatine kinase (CK) and transaminases, advice concerning diet, smoking and physical exercise as well as pharmacological treatment at the baseline and follow-up visits were also collected. The reasons why the LDL-C therapeutic targets were not achieved were ascertained from the follow-up visit.

The primary dependent variable was the percentage of patients that achieved their LDL-C therapeutic target as established by the 2012 European Guidelines12: LDL-C <100mg/dl (or non-HDL cholesterol <130mg/dl in patients with triglyceride levels >400mg/dl) objective for patients with high vascular risk and <70mg/dl (or non-HDL cholesterol <100mg/dl in patients with triglyceride levels >400mg/dl) or a fall of 50% or more versus the baseline concentration for patients with very high vascular risk.

The reasons for failing to achieve the LDL-C therapeutic targets were grouped into three sections. The first analysed the drug-related causes: having reached the maximum tolerated dose of the medication and onset of side effects (myalgia without CK elevation, CK elevation and transaminase elevation). The second analysed the doctor-related causes: obstacles to prescribing certain drugs, clinical inertia defined as an unjustified failure to modify the treatment when the therapeutic target is not achieved, failing to follow the European Guidelines,12 prescription cancellation by another doctor and the doctor deeming the therapeutic target to have been achieved in patients with LDL-C levels above target levels. The third group analysed the patient-related causes: comorbidity or polypharmacy discouraged treatment intensification, inability to afford the treatment, non-adherence to treatment and failure to complete follow-up. The causes were not mutually exclusive.

Statistical analysisSample sizeTo estimate a therapeutic target attainment rate of 45%,10 with a 95% confidence interval and 7% precision, it was necessary to enrol 194 patients. Assuming a loss to follow-up rate of 20%, a sample size of 238 patients was required.

The categorical variables were summarised by absolute and relative frequency. The continuous variables were summarised by mean and standard deviation. In the event of non-normal distribution, they were summarised by median and the 25th and 75th percentiles (first and third quartiles).

The quantitative values measured in the two visits were compared using the Student's t test of paired samples or the Wilcoxon tests depending on the proximity of the values to Gaussian distribution. McNemar's test was used to compare the qualitative values of paired samples.

The two-tailed level of statistical significance used was 0.05. The software IBM® SPSS® Statistics v.22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, New York) was used for the statistical analysis.

ResultsSixteen (55.2%) of the 29 lipid and vascular risk units that made up the Network of Lipid and Arteriosclerosis Units of Catalonia (Xarxa d’Unitats de Lípids i Arteriosclerosi) participated, and a total of 243 patients were enrolled. The median time between the two visits was 23 months, with an interquartile range of 11.3–29.4 months, and the median number of follow-up visits was four, with an interquartile range of three to five. Twenty-two patients (8.3%) were excluded for failing to attend any of the subsequent follow-up visits.

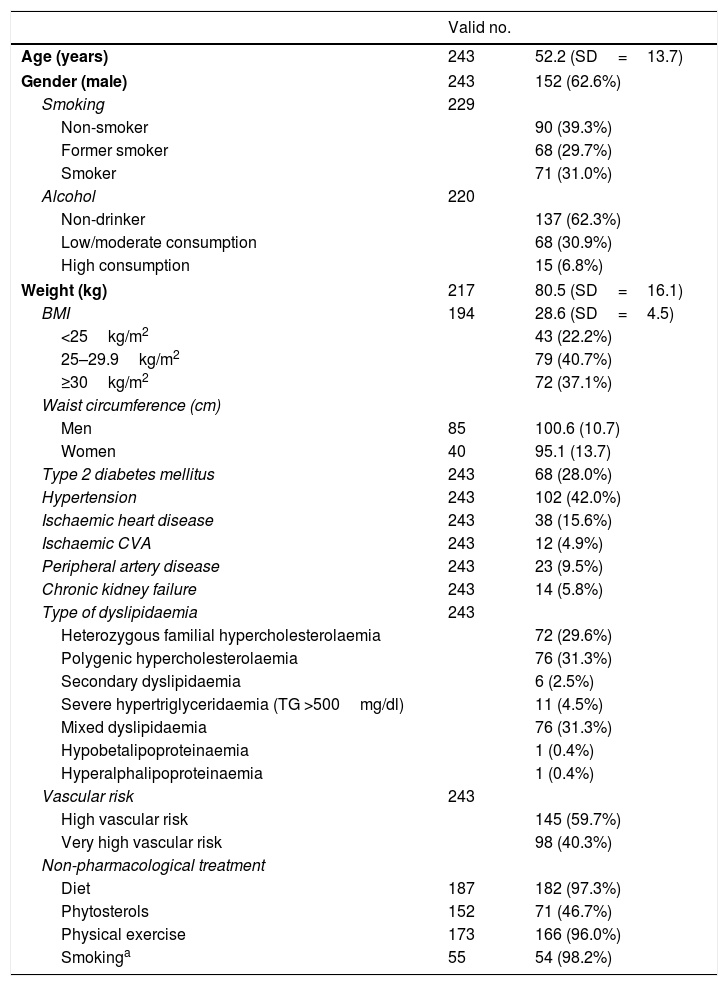

The demographic, anthropometric and clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 52.2 years (SD 13.7) and 62.6% of patients were male. 40.3% presented very high vascular risk.

Demographic, anthropometric and clinical characteristics of the 243 patients.

| Valid no. | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 243 | 52.2 (SD=13.7) |

| Gender (male) | 243 | 152 (62.6%) |

| Smoking | 229 | |

| Non-smoker | 90 (39.3%) | |

| Former smoker | 68 (29.7%) | |

| Smoker | 71 (31.0%) | |

| Alcohol | 220 | |

| Non-drinker | 137 (62.3%) | |

| Low/moderate consumption | 68 (30.9%) | |

| High consumption | 15 (6.8%) | |

| Weight (kg) | 217 | 80.5 (SD=16.1) |

| BMI | 194 | 28.6 (SD=4.5) |

| <25kg/m2 | 43 (22.2%) | |

| 25–29.9kg/m2 | 79 (40.7%) | |

| ≥30kg/m2 | 72 (37.1%) | |

| Waist circumference (cm) | ||

| Men | 85 | 100.6 (10.7) |

| Women | 40 | 95.1 (13.7) |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 243 | 68 (28.0%) |

| Hypertension | 243 | 102 (42.0%) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 243 | 38 (15.6%) |

| Ischaemic CVA | 243 | 12 (4.9%) |

| Peripheral artery disease | 243 | 23 (9.5%) |

| Chronic kidney failure | 243 | 14 (5.8%) |

| Type of dyslipidaemia | 243 | |

| Heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia | 72 (29.6%) | |

| Polygenic hypercholesterolaemia | 76 (31.3%) | |

| Secondary dyslipidaemia | 6 (2.5%) | |

| Severe hypertriglyceridaemia (TG >500mg/dl) | 11 (4.5%) | |

| Mixed dyslipidaemia | 76 (31.3%) | |

| Hypobetalipoproteinaemia | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Hyperalphalipoproteinaemia | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Vascular risk | 243 | |

| High vascular risk | 145 (59.7%) | |

| Very high vascular risk | 98 (40.3%) | |

| Non-pharmacological treatment | ||

| Diet | 187 | 182 (97.3%) |

| Phytosterols | 152 | 71 (46.7%) |

| Physical exercise | 173 | 166 (96.0%) |

| Smokinga | 55 | 54 (98.2%) |

BMI: body mass index; TG: triglycerides.

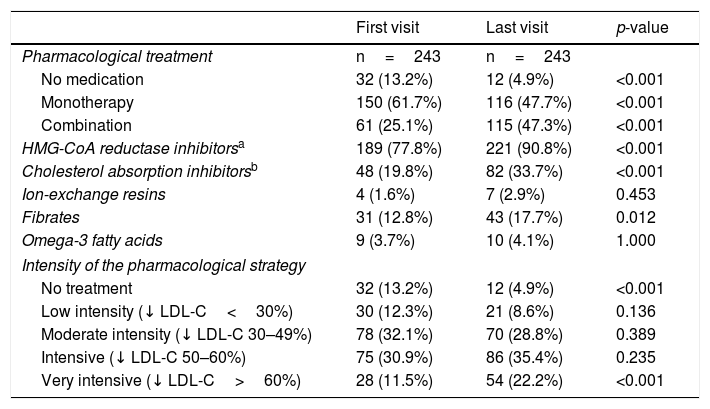

86.8% of patients were receiving lipid-lowering pharmacological treatment at the first visit, which increased to 95.0% by the last visit (p<0.001). Statins were the most widely used drugs at both visits. At the first visit, the percentage of patients on combination lipid-lowering treatment was 25.1%, versus 47.3% at the last visit (p<0.001). Ezetimibe was the most-used drug after statins, with a significant increase between the two visits (19.8% vs 33.7%; p<0.001). It was administered in combination with statins in 95.9% of patients at the first visit and 100% of patients at the last visit. At the first visit, 44.4% of patients were receiving low-moderate lipid-lowering therapy, which subsequently fell to 37.4% by the end of follow-up. Meanwhile, 42.4% were receiving intensive-very intensive therapy at the first visit, which rose to 57.6% at the last visit (Table 2).

Lipid-lowering pharmacological treatment at the two visits conducted.

| First visit | Last visit | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacological treatment | n=243 | n=243 | |

| No medication | 32 (13.2%) | 12 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| Monotherapy | 150 (61.7%) | 116 (47.7%) | <0.001 |

| Combination | 61 (25.1%) | 115 (47.3%) | <0.001 |

| HMG-CoA reductase inhibitorsa | 189 (77.8%) | 221 (90.8%) | <0.001 |

| Cholesterol absorption inhibitorsb | 48 (19.8%) | 82 (33.7%) | <0.001 |

| Ion-exchange resins | 4 (1.6%) | 7 (2.9%) | 0.453 |

| Fibrates | 31 (12.8%) | 43 (17.7%) | 0.012 |

| Omega-3 fatty acids | 9 (3.7%) | 10 (4.1%) | 1.000 |

| Intensity of the pharmacological strategy | |||

| No treatment | 32 (13.2%) | 12 (4.9%) | <0.001 |

| Low intensity (↓ LDL-C<30%) | 30 (12.3%) | 21 (8.6%) | 0.136 |

| Moderate intensity (↓ LDL-C 30–49%) | 78 (32.1%) | 70 (28.8%) | 0.389 |

| Intensive (↓ LDL-C 50–60%) | 75 (30.9%) | 86 (35.4%) | 0.235 |

| Very intensive (↓ LDL-C>60%) | 28 (11.5%) | 54 (22.2%) | <0.001 |

LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

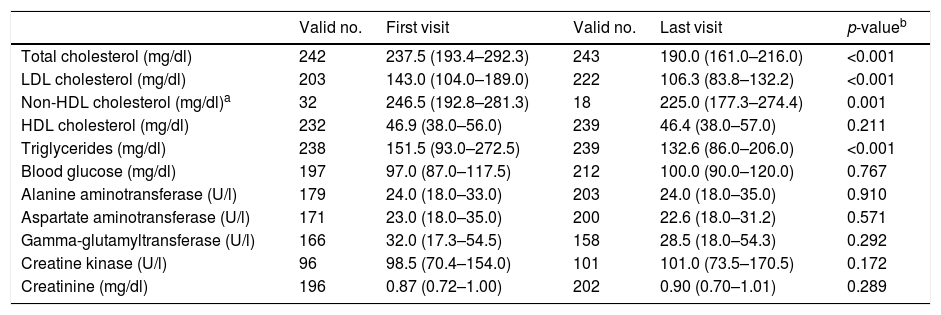

The changes in lipid profile are shown in Table 3. A significant reduction in total cholesterol, LDL-C, non-HDL cholesterol and triglycerides was observed between the two visits. No differences in HDL-C or significant transaminase increases were observed between the two visits.

Lipid profile at the two visits conducted.

| Valid no. | First visit | Valid no. | Last visit | p-valueb | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl) | 242 | 237.5 (193.4–292.3) | 243 | 190.0 (161.0–216.0) | <0.001 |

| LDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 203 | 143.0 (104.0–189.0) | 222 | 106.3 (83.8–132.2) | <0.001 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dl)a | 32 | 246.5 (192.8–281.3) | 18 | 225.0 (177.3–274.4) | 0.001 |

| HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 232 | 46.9 (38.0–56.0) | 239 | 46.4 (38.0–57.0) | 0.211 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dl) | 238 | 151.5 (93.0–272.5) | 239 | 132.6 (86.0–206.0) | <0.001 |

| Blood glucose (mg/dl) | 197 | 97.0 (87.0–117.5) | 212 | 100.0 (90.0–120.0) | 0.767 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (U/l) | 179 | 24.0 (18.0–33.0) | 203 | 24.0 (18.0–35.0) | 0.910 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (U/l) | 171 | 23.0 (18.0–35.0) | 200 | 22.6 (18.0–31.2) | 0.571 |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (U/l) | 166 | 32.0 (17.3–54.5) | 158 | 28.5 (18.0–54.3) | 0.292 |

| Creatine kinase (U/l) | 96 | 98.5 (70.4–154.0) | 101 | 101.0 (73.5–170.5) | 0.172 |

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 196 | 0.87 (0.72–1.00) | 202 | 0.90 (0.70–1.01) | 0.289 |

Median (25th percentile–75th percentile).

HDL-C: high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C: low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

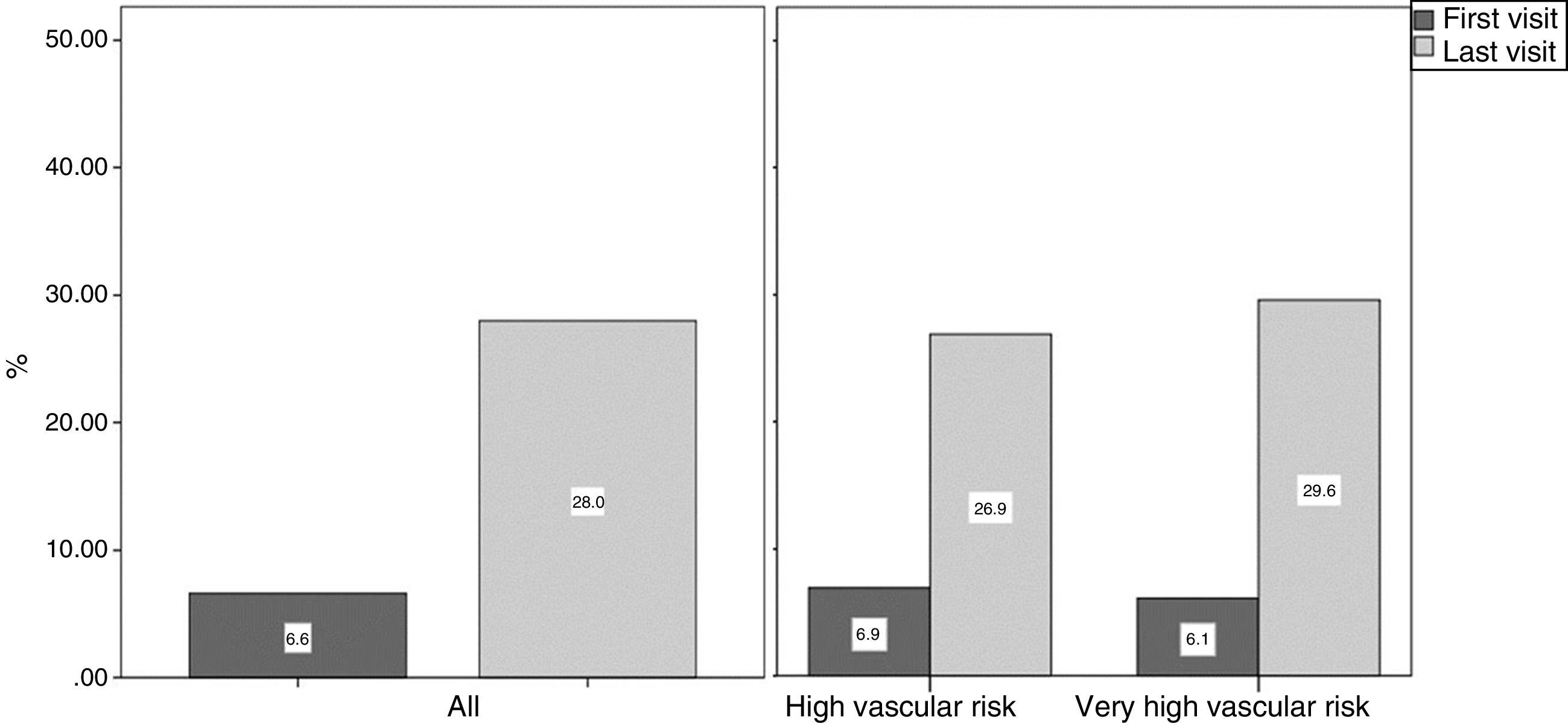

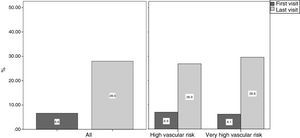

6.6% (95% CI: 3.8–10.5) of patients attained the LDL-C therapeutic target at the first visit. 28.0% (95% CI: 22.4–34.1) attained the LDL-C therapeutic target at the last visit. In terms of vascular risk, 26.9% (95% CI: 19.9–34.9) of patients with high vascular risk and 29.6% (95% CI: 20.8–39.7) of patients with very high vascular risk attained the therapeutic target (Fig. 1). Approximately 9.1% of patients who did not achieve the LDL-C therapeutic target at the last visit did so at some point during follow-up: 9.9% for high vascular risk patients and 12.1% for patients with very high vascular risk.

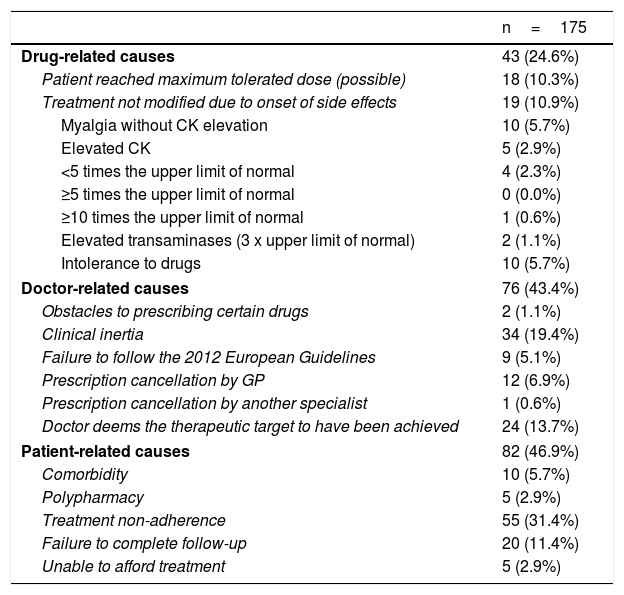

Table 4 outlines the reasons for failing to achieve the LDL-C therapeutic target. The most common causes were patient-related (46.9%), primarily non-adherence to treatment (31.4%) and failure to complete follow-up (11.4%). Doctor-related causes accounted for 43.4%, primarily clinical inertia (19.4%) and the doctor having deemed the therapeutic target to have been attained despite LDL-C levels in excess of the reference values (13.7%). The doctor acknowledged not having followed the recommendations of the European Guidelines in 5.1% of cases. Drug-related causes accounted for 24.6% of cases, primarily the onset of side effects.

Reasons for failing to achieve the LDL-C therapeutic targets.

| n=175 | |

|---|---|

| Drug-related causes | 43 (24.6%) |

| Patient reached maximum tolerated dose (possible) | 18 (10.3%) |

| Treatment not modified due to onset of side effects | 19 (10.9%) |

| Myalgia without CK elevation | 10 (5.7%) |

| Elevated CK | 5 (2.9%) |

| <5 times the upper limit of normal | 4 (2.3%) |

| ≥5 times the upper limit of normal | 0 (0.0%) |

| ≥10 times the upper limit of normal | 1 (0.6%) |

| Elevated transaminases (3 x upper limit of normal) | 2 (1.1%) |

| Intolerance to drugs | 10 (5.7%) |

| Doctor-related causes | 76 (43.4%) |

| Obstacles to prescribing certain drugs | 2 (1.1%) |

| Clinical inertia | 34 (19.4%) |

| Failure to follow the 2012 European Guidelines | 9 (5.1%) |

| Prescription cancellation by GP | 12 (6.9%) |

| Prescription cancellation by another specialist | 1 (0.6%) |

| Doctor deems the therapeutic target to have been achieved | 24 (13.7%) |

| Patient-related causes | 82 (46.9%) |

| Comorbidity | 10 (5.7%) |

| Polypharmacy | 5 (2.9%) |

| Treatment non-adherence | 55 (31.4%) |

| Failure to complete follow-up | 20 (11.4%) |

| Unable to afford treatment | 5 (2.9%) |

The causes are not mutually exclusive.

Compared to previous studies conducted in secondary care,4,9,10,15 this study found an improvement in the attainment of LDL-C targets in patients with high and very high vascular risk according to the 2012 European guidelines.12 Around one third of patients treated at lipid and vascular risk units achieved the LDL-C target. Patient non-adherence, followed by clinical inertia and side effects, are the primary causes that could explain these results.

In studies conducted at specialised clinics in Spain,9,10 the LDL-C target level <70mg/dl was achieved in less than 20% of very high-risk patients. These findings are consistent with the published results of the EUROASPIRE IV study,4 which found that only 19.5% of patients attained LDL-C levels <70mg/dl despite the fact that 85.7% were receiving statins. In our study, 29.6% of very high-risk patients met the target, bettering the 27.3% of patients published by the REPAR Registry.20 It is surprising that in specialised clinics where it is taken for granted that the healthcare professionals are aware of the importance of attaining the treatment goals recommended by the CPGs, fewer than 30% of patients meet this target.

Although not conducted in the specific setting of lipid units, the LIPICERES study21 found that 52.3% of patients achieved target LDL-C levels <70mg/dl. Greater control was observed in 2015 than in previous years. The authors attribute this improvement to the publication of the IMPROVE-IT study.22

If we consider the less-stringent targets of the Preventive Activities and Health Promotion Programme (Programa de Actividades Preventivas y de Promoción de la Salud, PAPPS)23 applicable and current during the study period, 59.3% of high-risk patients (primary prevention, LDL-C target <130mg/dl) and 53.1% of very high-risk patients (secondary prevention, LDL-C target <100mg/dl) achieved the LDL-C goal. However, these goals were disputed by specialists for not following the European Guidelines.12

It is striking that 93.4% of patients who attended lipid units for the first time did not achieve the LDL-C target, despite the fact that 86.8% were receiving lipid-lowering drugs. Statins were the drugs most commonly used, consistent with other studies.4,10,20 In our study, more patients received combination therapy with cholesterol absorption inhibitors than in the EDICONDIS10 and REPAR20 studies.

The greater number of patients who attained the LDL-C target in our study could be explained by the change to the very intensive treatment strategy used (Table 2), comparable to the EDICONDIS-ULISEA study,10 in which use of the more intensive treatment increased from 15.7% to 29.9%.

Non-adherence to treatment was the main barrier to achieving the treatment goals in our study. According to Fuster,24 treatment adherence did not exceed 60% and more than 50% of patients with chronic conditions decided to discontinue treatment. In studies assessing treatment adherence in dyslipidaemia,25,26 the percentage of non-compliant patients ranges from 26.7% to 46.7%.

Treatment adherence recommended by the CPGs is associated with the reduced onset of severe CV events and healthcare cost savings.27 A lack of treatment adherence by the patient should be considered as a cause of treatment failure. Concern over the onset of side effects in the future, the cost of treatment, possible interactions with other medicines or patients’ perception of a treatment's lack of efficacy, its short-term action or its ineffectiveness for CV prevention can all be associated with the presence of side effects.28

In terms of doctor-related causes, clinical inertia was the primary factor. In our study, clinical inertia was associated with greater non-adherence to treatment. A total of 50% of patients subjected to clinical inertia were non-compliant, versus 27% of patients not subjected to clinical inertia (p=0.009). The inertia study,15 which evaluated the degree of clinical inertia in the outpatient management of dyslipidaemia in patients with ischaemic heart disease, found 42.8% of consultations involved clinical inertia. According to cardiologists, one of the most common causes of undertreatment associated with clinical inertia was a lack of familiarity with the CPGs and the lack of protocols.

Studies that have analysed the reasons for failing to achieve LDL-C targets in secondary care9,15,29 in high- or very high-risk patients have been based on doctor surveys and questionnaires.15,29 The study by Galve et al.,29 which employed the Delphi method, recognised the complexity and debate surrounding the treatment of dyslipidaemia. It was mutually agreed that the number of patients with very high CV risk who meet the recommended LDL-C targets is inadequate and that clinical inertia is common in clinical practice.

In 13.7% of cases where the LDL-C target was not met, the doctor considered that it had been. In 54.2% of these patients, LDL-C levels did not exceed 10% of the target (69.2% for high-risk patients and 36.4% for very high-risk patients). It may be that in these cases the doctor may have evaluated individual variability and the variability of the analytical method, as well as the risks and benefits of intensifying treatment, before concluding that treatment intensification is not necessary.

The most commonly reported side effects attributed to statins30,31 are muscle disorders and liver disease. The onset of side effects in our study was similar to that reported in the literature as the cause cannot be modified.

It is important to identify the modifiable causes for failing to achieve the LDL-C therapeutic target recommended by the CPGs in actual clinical practice in lipid units, and to thereby understand the reason why specialists who have the necessary expertise and tools do not achieve this goal in a greater proportion of cases. A study performed in clinical practice32 involving high-risk patients found that follow-up by a specialised unit and the implementation of CPGs improved the control of CV risk factors and led to a greater reduction in three-year morbidity and mortality.

In this light, rather than lamenting the general failure to achieve LDL-C targets, strategies must be developed aimed at improving these outcomes. It is only by fully understanding the reasons that real solutions can be found. Extra effort must be made to not put the blame on the patient, to find ways to improve treatment adherence where side effects do not impede the administration of treatment and to overcome clinical inertia.33,34 Three quarters of the reasons why the LDL-C treatment targets are not met are modifiable. Clinical inertia can be overcome by applying an appropriate methodology, and the treatment goals can be met with the cholesterol-lowering drugs that are currently available. To achieve this, it is essential to be coherent with the CPGs and the implications of attaining the therapeutic targets, as well as to optimise the implementation of the available lipid-lowering strategies.33–35

LimitationsThe limitations of the Retrospective, Observational, Therapeutic Target Management Study (EROMOT) mainly derive from its retrospective design. Nevertheless, this study contributes specific knowledge on the reasons why treatment targets are not met and the intensity of the therapeutic strategies used in lipid and vascular risk units, as well as the efficacy of lipid-lowering drugs in actual clinical practice.

ConclusionDespite a significant improvement in attaining LDL-C targets in lipid and vascular risk units, as well as increased uptake of very intensive treatment strategies, there is still much room for improvement. Fully understanding the reasons why LDL-C therapeutic targets are not met could help us to design strategies to optimise use of the available lipid-lowering drugs and thereby improve CV morbidity and mortality as cost-effectively as possible in actual clinical practice.

Ethical responsibilitiesProtection of people and animalsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this research.

Data confidentialityThe authors declare that they have followed the protocols implemented in their place of work regarding the publication of patient data.

Right to privacy and informed consentThe authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

FundingThis study was partially funded by an unrestricted grant from MSD España to the Network of Lipid and Arteriosclerosis Units of Catalonia (Xarxa d’Unitats de Lípids i Arteriosclerosi de Catalunya) to support atherosclerosis research activities.

Conflicts of interestFor this study, the authors declare that there was no interference in the attaining or interpretation of the results and that they therefore have no conflicts of interest.

Some of the authors have received fees for conferences and/or scientific advice from various pharmaceutical companies, as detailed below.

Dr Morales has received conference fees from MSD España, Rubió and Sanofi.

Dr Plana has received conference fees from Alexion, Amgem, Ferrer, MSD, Rubió and Sanofi.

Dr Masana has received conference and scientific advice fees from Amgen, MSD, Recordati and Sanofi.

Dr Pedro-Botet has received conference fees from Astra Zeneca, Esteve, Ferrer, Merck, Mylan and Sanofi.

Drs Arnau, Matas, Mauri, A. Vila, Ll. Vila, Soler and Montesinos declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Alphabetic list of the group members by lipid and vascular risk unit of the Xarxa d’Unitats de Lípids i Arteriosclerosi. EROMOT-XULA group.

Enric Ballestar Mas (Hospital de Mataró, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Mataró, Barcelona).

Mònica Berrocal Guevara (Fundació Hospital/Asil de Granollers, Granollers, Barcelona).

Rosa María Borrallo Almans (Consorci Sanitari de Terrassa, Hospital de Terrassa, Terrassa, Barcelona).

Assumpta Caixàs Pedragós (Hospital Parc Taulí de Sabadell, Sabadell, Barcelona).

Elisenda Climent (Hospital del Mar de Barcelona, Barcelona).

Montserrat García Cors (Hospital General de Catalunya, Sant Cugat del Vallès, Barcelona).

Carolina Guerrero Buitrago (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Martorell, Martorell, Barcelona).

Jordi Grau Amorós (Hospital Municipal de Badalona, Badalona, Barcelona).

Daiana Ibarretxe Guerediaga (Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus, Reus, Tarragona).

Carlos Jericó Alba (Hospital de Sant Joan Despí Moisès Broggi, Consorci Sanitari Integral, Sant Joan Despí, Barcelona).

M. Teresa Julian Alagarda (Hospital de Mataró, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Mataró, Barcelona).

Esteve Llargués Rocabruna (Fundació Hospital/Asil de Granollers, Granollers, Barcelona).

Paquita Montaner Batlle (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Martorell, Martorell, Barcelona).

Abel Mujal Martínez (Hospital Parc Taulí de Sabadell, Sabadell, Barcelona).

Eduarda Pizarro Lozano (Hospital de Mataró, Consorci Sanitari del Maresme, Mataró, Barcelona).

Rafael Ramírez Montesinos (Hospital de Santa Tecla, Tarragona).

Joaquim Ripollés Edo (Hospital Sant Joan de Déu de Martorell, Martorell, Barcelona).

Cèlia Rodríguez-Borjabad (Hospital Universitari Sant Joan de Reus, Reus, Tarragona).

Elisabeth Sánchez Pujol (Fundació Hospital/Asil de Granollers, Granollers, Barcelona).

Mònica Vila Vall-llovera (Fundació Hospital/Asil de Granollers, Granollers, Barcelona).

Alberto Zamora Cervantes (Hospital de Blanes, Blanes, Girona).

The full list of members of the EROMOT-XULA research group can be found in Annex 1.

Please cite this article as: Morales C, Plana N, Arnau A, Matas L, Mauri M, Vila À, et al. Causas de no consecución del objetivo terapéutico del colesterol de las lipoproteínas de baja densidad en pacientes de alto y muy alto riesgo vascular controlados en Unidades de Lípidos y Riesgo Vascular. Estudio EROMOT. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2018;30:1–9.