The treatment of dyslipidemia exhibits wide variability in clinical practice and important limitations that make lipid-lowering goals more difficult to attain. Getting to know the management of these patients in clinical practice is key to understand the existing barriers and to define actions that contribute to achieving the therapeutic goals from the most recent Clinical Practice Guidelines.

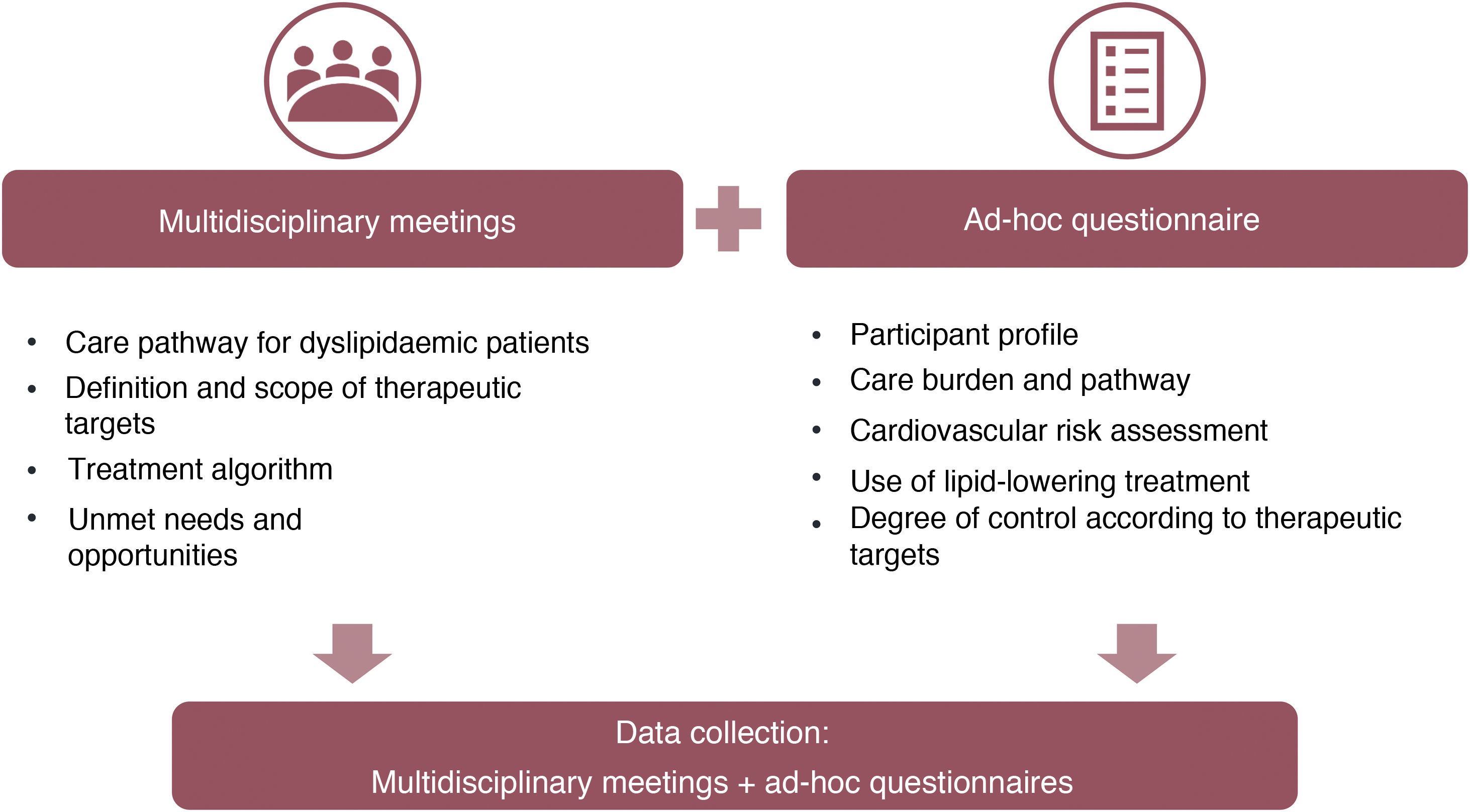

MethodsObservatory where the information gathered is based on routine clinical practice and the experience from the healthcare professionals involved in the treatment of dyslipidemia in Spain. The information is collected by health area through: (i) face-to-face meeting with three different medical specialties and (ii) quantitative information related to hypercholesterolemia patients’ management (ad-hoc questionnaire). Information includes patients’ profiles, assistance burden, guidelines and protocols used, goal attainment, limitations and opportunities in clinical practice.

Results145 health areas are planned to be included, with the participation of up to 435 healthcare professionals from the 17 Autonomous Regions of Spain. Information collection will result in aggregated data from over four thousand patients.

ConclusionsThis Observatory aims to understand how hypercholesterolemia is being treated in routine clinical practice in Spain. Even though the preliminary results show important improvement areas in the treatment of dyslipidemias, mechanisms to drive a change towards health outcomes optimization are also identified.

El tratamiento de las dislipemias presenta gran variabilidad en la práctica clínica e importantes limitaciones que dificultan la consecución de los objetivos terapéuticos. Por ello, se ha diseñado un proyecto para evaluar el control de la dislipemia en España, identificar los puntos de mejora y tratar de optimizarlo. El objetivo de este artículo es describir la metodología del Observatorio del tratamiento del paciente dislipémico en España.

MétodosObservatorio de recogida de información basada en la práctica clínica habitual y experiencia de los profesionales de la salud que atienden a pacientes dislipémicos en España. El Observatorio recoge información por área sanitaria, a través de: (i) reunión presencial con tres especialidades médicas diferentes y (ii) información cuantitativa de manejo de pacientes con hipercolesterolemia (cuestionario ad-hoc). La información incluye perfiles de paciente atendidos, carga asistencial, guías y protocolos utilizados, grado de control alcanzado, limitaciones y oportunidades de mejora en práctica clínica.

ResultadosSe busca incluir 145 áreas sanitarias, contando con la participación de hasta 435 profesionales médicos de las 17 Comunidades Autónomas de España. La información recogida de los participantes permitirá disponer de datos agregados de más de cuatro mil pacientes.

ConclusionesEste Observatorio pretende conocer cómo se está tratando la hipercolesterolemia en la práctica clínica en España. Aunque los resultados preliminares muestran una importante área de mejora en el tratamiento de las dislipemias, se identifican también mecanismos para impulsar un cambio hacia la optimización de resultados en salud.

Dyslipidaemia is associated with the onset of cardiovascular disease (CVD) such as myocardial infarction and stroke, the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide.1–3 According to data from the Spanish National Institute of Statistics, diseases of the circulatory system were the leading cause of death in Spain in 2018 (120,859 deaths, 28.3% of total deaths), ahead of cancer (26.4%).4 Therefore, their appropriate prevention and treatment should be considered a healthcare priority in clinical practice.

Dyslipidaemia is one of the main modifiable cardiovascular risk factors (CVR).5 In Spain, 50% of the adult population has a total cholesterol (TC)>200mg/dL.6 Of these, 69% correspond to pure hypercholesterolaemia, 26% to mixed dyslipidaemia and 5% to hypertriglyceridaemia.7 Of the dyslipidaemias, hypercholesterolaemia is considered to account for 54% of the potential risk of myocardial infarction,3 and about 86.8% of patients diagnosed with dyslipidaemia have been found to have an additional CVR factor, primarily established CVD.7

Control of hypercholesterolaemia can be achieved by reducing LDL-C levels, based on dietary/hygiene and/or pharmacological measures.5 With the use of statins, it is estimated that for every reduction in LDL-C levels of 1mmol/L (39mg/dL), the relative cardiovascular risk is reduced by 22%.8 The most recent dyslipidaemia treatment guidelines indicate target thresholds that depend on the patient's CVR and that, in patients with established CVD or very high CVR, reduction should be at least 50% of baseline to achieve an LDL-C<55mg/dL.9,10

Different therapeutic tools are currently available that could achieve target levels of LDL-C control11; however, the evidence indicates that this is still far from being achieved. In Spain, different studies indicate that LDL-C targets are only achieved in 26%–28% of patients at high or very high CVR,12,13 39% in patients on optimised lipid-lowering therapy,14 but this is according to previous targets, which were less demanding than the current targets. Other studies in the European population show that only 33% of dyslipidaemic patients achieve LDL-C targets, which is 18%–20% in patients at very high CVR.15,16

In addition to this low level of control observed in clinical practice, the 2019 published reference guidelines have not been adequately disseminated or implemented partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, the new guidelines introduce much more ambitious and difficult to achieve LDL-C control targets.

All this means the scientific societies need to know how dyslipidaemic patients are currently being controlled in Spain, and how health professionals can be supported so that, each in their own area of care can help reduce CVR in these patients, and achieve improved health outcomes. Not only do the results of LDL-C reduction need to be known, but also the differences between regions, because, for example, there is different access to certain lipid-lowering treatments.17,18

Spain’s dyslipidaemia observatory, a project led by the Spanish Society of Cardiology (SEC) and the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis (SEA), was created to learn about healthcare practice in the treatment of dyslipidaemic patients and to identify measures that can help the targets recommended by current clinical practice guidelines be achieved in routine clinical practice. This article describes the design of the observatory.

MethodsStudy designThe dyslipidaemia observatory is an initiative of two scientific societies (SEC and SEA), and therefore its design, selection of participants and health areas, study materials, and results have been validated by a Scientific Committee comprising a total of 10 experts (five from each society).

The study is based on consensus methodologies that enable the inclusion of qualitative information based on the experience and opinion of the doctors participating in the study, and quantitative information collected through an ad hoc study questionnaire (Fig. 1).

Initially, the study was designed to collect information from clinical practice in 89 health areas (267 participating doctors). In June 2021, due to the potential value of the information being collected, we decided to increase the number of health areas to 145 (435 participating doctors).

Study populationFor the purposes of the study, four profiles of patients with hypercholesterolaemia were defined, which were not mutually exclusive: (i) patients in primary prevention; (ii) patients in secondary prevention; (iii) patients with diabetes mellitus; (iv) patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia. Other patient profiles were also considered if mentioned spontaneously during the working meetings.

Data collectionAll data (qualitative and quantitative) were centrally managed and analysed through the study's contract research organisation (CRO) (IQVIA). IQVIA also moderated the face-to-face meetings.

Qualitative data collection – face-to-face meetingsQualitative information was collected from the comments and discussion generated in the different face-to-face working sessions with experts in the management of hypercholesterolaemia. Each meeting was attended by three experts in the treatment of dyslipidaemia with different professional profiles belonging to the same health area (geographical area made up of one or more primary care centres and a referral hospital): principally family and community medicine, cardiology, internal medicine, and endocrinology (other specialties were occasionally included depending on the healthcare situation of the health area).

The sessions were moderated based on a common consensual discussion guide, including four thematic blocks:

- •

Care pathway: care management of the patient with hypercholesterolaemia, including from time of diagnosis to long-term follow-up. For each patient profile, a discussion was generated about the diagnostic process and the professionals involved in it, the decision-making process in the management (therapeutic or otherwise) of the patient, patient monitoring (during the first year and in the long term), and referral processes (if applicable).

- •

Therapeutic targets and CVR assessment: procedures for CVR assessment in each case, key variables, or parameters in defining LDL-C targets for each CVR profile, and the degree or potential for achieving these targets in clinical practice.

- •

Therapeutic management: main therapeutic algorithms used in clinical practice to treat the different profiles of patients with hypercholesterolaemia (type of drugs used and lines of treatment).

- •

Unmet needs and opportunities for improvement: main unmet needs perceived by health professionals related to the treatment of dyslipidaemia and potential opportunities or proposals for improvement.

The participants at each meeting were invited to complete a survey questionnaire, consisting of 30 questions (supplementary material). The questionnaire was emailed individually to each participant after the meeting. The information collected in the questionnaire referred to each participant’s individual reality, considering measurable and quantifiable aspects, and data based on their clinical opinion:

- •

General profile of the participant: age, specialty, region of practice, type of centre (hospital/health centre, public/private), and specialty.

- •

Care burden: estimate of the number of patients per week visited for any cause, estimate of the percentage of patients treated with a lipid-lowering drug, and estimate of the distribution of patients according to study profiles.

- •

Care pathway: guidelines, protocols or consensus documents used for the diagnosis of dyslipidaemia, definition of therapeutic targets, patient monitoring and/or choice of treatment.

- •

Cardiovascular risk: frequency with which CVR is assessed, scales used, estimate of the distribution of patients according to CVR, normality thresholds (LDL-C) used in laboratory analyses.

- •

Treatment: existence of prescription indicators or usage guidelines for statins, ezetimibe or proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9i), treatment used in target patient profiles, treatment changes (frequency of change and reason) and estimate of the percentage of patients that are intolerant to statins.

- •

Control: estimate of the percentage of controlled patients (clinical criteria and according to the LDL-C targets of the 2019 guidelines).

To contrast clinical opinion with real data, aggregate data were collected from 10 consecutive dyslipidaemic patients that the participant had recently visited: type of patient (primary/secondary prevention), relevant comorbidities, CVR profile, treatment received (therapeutic group), and LDL-C range achieved.

Analysis of resultsThe qualitative data obtained at each meeting were recorded in the minutes of the meeting and processed by consensus analysis, identifying differences and similarities in the participants' responses.

Quantitative data were analysed descriptively (Microsoft Excel) including mean, standard deviation (SD), median and interquartile range, maximum and minimum, for continuous variables, and n (%) for categorical variables. Results were disaggregated by specialty and by region. No comparative statistical analysis was performed.

Ethical considerationsAll the information in the study was collected according to the experience and opinion of the different participating physicians.

Since no individual patient data were recorded in the study and no medical history data were collected, approval by the Ethics Committee of reference was not required, nor was signed informed consent from the patient.

ResultsRunning of sessions in different health areasFifteen initial meetings were held (Phase I) between October and December 2020, from which a first content analysis was performed to determine the suitability of: (i) the moderation guide and structure of the sessions and (ii) the contents and structure of the answers collected in the study questionnaire. In January 2021, the final materials were reviewed and validated by the study's Scientific Committee to then proceed to Phase II, with a total of 74 additional meetings/health areas.

The completion of Phases I and II of the study yielded data on a national level and for 17 Autonomous Communities. With a total of 267 participants providing qualitative information and data from 253 responses to the study questionnaires (95% participation), there was a considerable source of information from which to draw relevant results. Most of the health areas included were referral hospitals, generally publicly owned, with a high volume of care. This, together with the low representation of private centres, could limit the interpretation of the study data. Therefore, the Scientific Committee proposed extending the health areas to include centres with different characteristics and referral populations, as well as private centres, which totalled 145 health areas.

The 145 sessions were completed by the date of the last meeting, December 2021. They covered the entire country, with regional representation according to the proportion of population in each Autonomous Community with respect to the national total (Table 1).

Distribution of health areas participating in Spain’s dyslipidaemia observatory.

| Variable | Meetings held* (n=145) | Patients includeda (n=4010) | Total population# (n=47394223) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autonomous Community | Andalusia | 25 (17%) | 730 (18%) | 8501450 (18%) |

| Aragon | 5 (3%) | 130 (3%) | 1331280 (3%) | |

| Balearic Islands | 2 (1%) | 60 (1%) | 1219423 (3%) | |

| Canary Islands | 5 (3%) | 140 (3%) | 2244423 (5%) | |

| Cantabria | 2 (1%) | 60 (1%) | 583904 (1%) | |

| Castilla La Mancha | 6 (4%) | 130 (3%) | 2049455 (4%) | |

| Castile and Leon | 11 (8%) | 330 (8%) | 2387370 (5%) | |

| Catalonia | 18 (12%) | 490 (12%) | 7669999 (16%) | |

| Ceuta | 1 (1%) | 10 (0%) | 83502 (0%) | |

| Community of Madrid | 18 (12%) | 520 (13%) | 6752763 (14%) | |

| Navarra | 2 (1%) | 50 (1%) | 657776 (1%) | |

| Valencian Community | 17 (12%) | 470 (12%) | 5045885 (11%) | |

| Extremadura | 5 (3%) | 150 (4%) | 1057999 (2%) | |

| Galicia | 10 (7%) | 230 (6%) | 2696995 (6%) | |

| La Rioja | 1 (1%) | 30 (1%) | 316197 (1%) | |

| Basque Country | 7 (5%) | 190 (5%) | 2185605 (5%) | |

| Principality of Asturias | 4 (3%) | 120 (3%) | 1013018 (2%) | |

| Region of Murcia | 6 (4%) | 170 (4%) | 1513161 (3%) | |

The number of meetings in each Autonomous Community is shown, followed by the percentage of the total number of meetings held in Spain in brackets.

The number of patients included by the participants in each Autonomous Community is shown, followed by the percentage of the total number of patients included in Spain in brackets.

The population in each Autonomous Community and the percentage of the total population in Spain as of 1 January 2021 is shown36.

Of the 435 participating physicians, 125 (28.7%) were family and community medicine practitioners, 142 (32.6%) specialists in cardiology, 103 (23.7%) in internal medicine, 61 (14%) in endocrinology, 3 (.7%) in nephrology, and 1 (.2%) in neurology.

DiscussionSpain’s dyslipidaemia observatory is a research project that aims to characterise the current variability in the treatment of hypercholesterolaemia, and in the establishment of therapeutic targets, and the degree of control achieved in clinical practice in the different health areas and regions of Spain.

Dyslipidaemia is a very prevalent health problem in our setting.7,19–22 It is also one of the main modifiable CVR factors, associated with high cardiovascular morbidity and mortality,1–3 and therefore a clear priority for action by scientific societies and health systems.23–25 The available evidence has shown that adequately reducing LDL-C, according to each patient’s CVR, is directly related to a reduction in the risk of a cardiovascular event and its complications.5,9,26,27 Therefore, the main target in the treatment of dyslipidaemia is to reduce LDL-C to the lowest possible levels in the shortest possible time,9 and it is essential to ensure adequate knowledge among the medical community and to raise awareness in patients and their circle.

The recommendations of the 20199 European Society of Cardiology (ESC)/European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines9 are the main clinical reference, supported by the recommendations for the treatment of dyslipidaemia in Spain.17,18 LDL-C targets are clearly defined by the patient's CVR and comorbidities, and evidence is available to support treatment decision-making.11 Nevertheless, the degree of control achieved in clinical practice is poor12,28 this could be attributed to factors such as underestimation of the patient's CVR, reluctance regarding potential side effects of treatment, low use of combined lipid-lowering therapy, lack of adherence and/or compliance to treatment, or therapeutic inertia.12 It should be borne in mind that prior therapeutic planning through the use of lipid-lowering treatment tables aimed at achieving therapeutic targets,11 the use of computerised tools incorporated into the clinical history,29 or the application of therapeutic algorithms30 significantly help achieve therapeutic targets, especially in patients at very high CVR.31

Pintó et al.32 observed that in Spain, in dyslipidaemic patients without other CVR factors, 51.9% of physicians set a target of LDL-C<130mg/dL (29% at LDL-C<160mg/dL). In patients with a CVR factor (hypertension, smoking, or diabetes), 49%–55% of physicians set a target of LDL-C<100mg/dL; and in patients with a cardiovascular complication, ischaemic heart disease, or stroke, 71%–88% of physicians aimed to achieve LDL-C<70mg/dL.32 These data already differ from the recommendations applicable at the time of the study,33 and are far from the current recommendations.9

The EUROASPIRE IV study showed that although 86% of patients with chronic coronary syndrome were prescribed statins, only 20% achieved the LDL-C target. 16 In the EUROASPIRE V study, the percentage of patients controlled in secondary prevention rose to 32%, although there were significant areas for improvement in the therapeutic management of these patients (16% without lipid-lowering treatment, and low use of statin and ezetimibe combination).34 In the recent DA VINTER study, the percentage of patients with chronic coronary syndrome who received statins rose to 32%. The DA VINCI study recently found that only 33% of patients achieved the 2019 therapeutic targets (18% in patients in secondary prevention).15 About 20% of patients treated with statins (of any intensity, with or without ezetimibe) were controlled, compared to 58% of patients receiving PCSK9i.15 Galve et al. found similar results, with 26% of patients in secondary prevention with a target LDL-C, and only 14% of the total treated with combination therapy.12 These findings, along with the fact that only 45% of treated patients were receiving a high-intensity statin and treatment was not intensified in 70% of cases,12 show ample room for improvement through optimising lipid-lowering therapy35 and suggest the need for additional therapies and mechanisms to lower LDL-C in patients at high and very high CVR.

The basis of the dyslipidaemia observatory is the need to understand and contextualise these data, in line with the healthcare situation in Spain. This study provides a detailed analysis of the reality of the management and treatment of dyslipidaemia in 145 health areas in Spain (86% of all the health areas), including analyses at national and regional level and by healthcare setting. This is the only study to combine a contextualised analysis of the situation of the treatment of dyslipidaemia, that considers not only data on control achieved, but also the reasons why control is not achieved and the needs and potential areas for improvement that could help improve healthcare practice, representing almost all health areas, as well as both the public and private settings where the disease is managed, and at a multidisciplinary level. The study also provides a different and complementary view to the available information, incorporating the needs reported by health professionals, which are often side-lined, after patient data and a proposal for value initiatives that could help improve how dyslipidaemia is managed in our setting.

The dyslipidaemia observatory, although pioneering and representative of the national situation in Spain, has some limitations, such as the fact that it is based mainly on the experiences and opinions of professionals. This limitation is minimised by the analysis of aggregate data from the last patients seen by the participants (clinical practice data), which also provides valuable information to contrast the practitioner's vision with the real situation in their practice. It is important to bear in mind that the observatory participants were professionals with a special interest in lipids, which may translate into greater knowledge of and compliance with the recommendations than health professionals in general. In this sense, extending the sample with randomised participation, could be considered.

ConclusionsPreventive interventions reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease, but are difficult to implement in practice. Treatment guidelines for dyslipidaemia are clear in terms of therapeutic targets, but achieving these targets is complex, especially considering our country’s regional variability. Spain’s dyslipidaemia observatory is a project led by the SEC and the SEA, which aims to establish how hypercholesterolaemia is being treated in clinical practice in Spain through a detailed analysis of 145 health areas, identifying measures to promote change and thus improve health outcomes.

FundingThis work is a study by the Spanish Society of Cardiology and the Spanish Society of Atherosclerosis, sponsored by Daiichi Sankyo Spain.

Conflict of interestsJuan Cosin-Sales: has received conference honoraria from Almirall, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferrer, MSD, Novartis, Organon, Rovi, Sanofi. He has participated in consulancies for Almirall, Amgen, MSD, Sanofi. He has received research grants from Amgen, Ferrer, MSD and Sanofi. Raquel Campuzano: has received conference honoraria from Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferrer, Mylan, MSD, Organon, Sanofi, Servier. Novartis. She has participated in consulancies for Novartis, Amgen, Sanofi, Servier. She has received collaborations in scientific or research projects for Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Ferrer, Organon, Servier, Novartis. José Luis Díaz: has received honoraria for lectures, consultancies, and scientific collaborations from Amgen, Bayer, Boëringher, BMS, Lilly, MSD, Mylan, Novartis, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Rovi, Rubió, Sanofi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Servier. Carlos Escobar: has received conference/consultancy honoraria from Almirall, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Esteve, Ferrer, MSD, Novartis, Organon, Rovi, Sanofi, Servier and Viatris. María Rosa Fernández: has received conference honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer, Daiichi-Sankyo, Organon, Rovi. She has participated in consultancies for Novartis, Amgen, Sanofi, Amarin. Juan José Gómez-Doblas: has received conference honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi, Daiichi-Sankyo, Organon, MSD. He has participated in consultancies for Amgen, Sanofi, Amarin. He has received contributions for scientific or research projects from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer and Daiichi-Sankyo. José María Mostaza: has participated in consultancies and/or conferences, or undertaken projects for Pfizer, Amarin, Ferrer, Sanofi, Amgen, Alter, Servier, Novartis and Daiichi-Sankyo. Juan Pedro-Botet: has recieved conference honoraria from Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Esteve, MSD, Sanofi and Viatris. He has participated in consultancies for Amarin, Amgen, Daiichi-Sankyo, Esteve, Ferrer, Sanofi and Viatris. Núria Plana: has received conference honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi, Daiichi-Sankyo Mylan, Alexion. Pedro Valdivielso: has received conference honoraria from Amgen, Sanofi, Ferrer, Amarin, Akcea, Sobi, MSD, Novartis, Daiichi-Sankyo. He has participated in consultances for Daiichi-Sankyo, Amgen, Sanofi, Akcea, Amarin. He has received research grants from Ferrer and Akcea.

The authors would like to thank all the participants in the dyslipidaemia observatory for the information provided, and for their involvement in identifying potential areas for improvement in the management of dyslipidaemic patients in each care area. The study had support from IQVIA to conduct and moderate the sessions, and in the scientific writing tasks.