Data is scarce on the distribution of different types of dyslipidaemia in Colombia. The primary objective was to describe the frequency of dyslipidaemias. The secondary objectives were: frequency of cardiovascular comorbidity, statins and other lipid-lowering drugs use, frequency of statins intolerance, percentage of patients achieving c-LDL goals, and distribution of cardiovascular risk (CVR).

Materials and methodsCross-sectional study with retrospective data collection from 461 patients diagnosed with dyslipidaemia and treated in 17 highly specialised centres distributed into six geographic and economic regions of Colombia.

ResultsMean (SD) age was 66.4 (±12.3) years and 53.4% (246) were women. Dyslipidaemias were distributed as follows in order of frequency: mixed dyslipidaemia (51.4%), hypercholesterolaemia (41.0%), hypertriglyceridaemia (5.4%), familial hypercholesterolaemia (3.3%), and low c-HDL (0.7%). The most prescribed drugs were atorvastatin (75.7%) followed by rosuvastatin (24.9%). As for lipid control, 55% of all patients, and 28.6% of those with coronary heart disease, did not achieve their personal c-LDL goal despite treatment. The frequency of statin intolerance was 2.6% in this study.

ConclusionsMixed dyslipidaemia and hypercholesterolaemia are the most frequent dyslipidaemias in Colombia. A notable percentage of patients under treatment with lipid-lowering drugs, including those with coronary heart disease, did not achieve specific c-LDL goals. This poor lipid control may worsen patient's CVR, so that therapeutic strategies need to be changed, either with statin intensification or addition of new drugs in patients with higher CVR.

Los datos sobre la distribución de las dislipidemias en Colombia son limitados. El objetivo primario de este estudio fue describir la frecuencia de las dislipidemias; los objetivos secundarios fueron: la frecuencia de comorbilidades cardiovasculares, el uso de estatinas y otros hipolipemiantes, la frecuencia de intolerancia a estatinas, el porcentaje de pacientes en metas de c-LDL, y estimar la distribución del riesgo cardiovascular (RCV).

Materiales y métodosEstudio transversal con recolección de datos retrospectiva que incluyó a 461 pacientes con diagnóstico de dislipidemia tratados en 17 centros cardiovasculares de alta complejidad en las 6 principales áreas geográficas y económicas de Colombia.

ResultadosLa media (DE) de edad de los pacientes incluidos fue de 66,4 (±12,3) años. El 53,4% (246) eran mujeres. Las dislipidemias se distribuyeron así: dislipidemia mixta (51,4%), hipercolesterolemia (41,0%), hipertrigliceridemia (5,4%), hipercolesterolemia familiar (3,3%) y c-HDL bajo (0,7%). El medicamento más prescrito fue atorvastatina (75,7%), seguido de rosuvastatina (24,9%). El 55% del total de pacientes y el 28,6% de aquellos con enfermedad coronaria no estaban en metas de c-LDL a pesar del tratamiento. La frecuencia de intolerancia a estatinas fue del 2,6%.

ConclusionesLa dislipidemia mixta y la hipercolesterolemia son las dislipidemias más frecuentes. Un porcentaje considerable de pacientes en tratamiento, incluidos aquellos con enfermedad coronaria, no lograron sus objetivos de c-LDL. Este inadecuado control lipídico influye en el RCV y requiere un cambio en las estrategias terapéuticas, intensificando el tratamiento con estatinas o adicionando nuevos fármacos en los pacientes con mayor RCV.

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ACVD) is the first cause of mortality worldwide1 as well as in Europe,2 the United States3 and Latin America.4 In Colombia, ACVD is the cause of 28% of deaths.4,5 It is estimated that more than 17 million deaths per year in the world are due to the presence of ACVD, and projections for 2030 foresee that this figure will rise to above 23 million deaths.6,7 Ischemic coronary disease and ictus are the two main causes of death due to ACVD in low or intermediate income countries.1

Atherosclerosis affect medium to large calibre vessels in a complex process that progresses silently. Immunoinflammatory mechanisms play a role in this, and clinical complications, lipid metabolism and most particularly that of cholesterol bound to low density lipoproteins (LDL-c), play a decisive role.8,9 Although epidemiological studies have indisputably shown the relationship between raised LDL-c and ACVD, this finding does not explain the whole associated increase in cardiovascular risk (CVR). Alterations in the levels of cholesterol associated with high density lipoproteins (HDL-c) and those of subtypes of LDL-c and HDL-c particles are also associated with ACVD.9,10 Thus the concept of atherogenic dyslipidaemia, defined by the presence of raised levels of triglycerides in the plasma, a low plasma concentration of HDL-c and high concentrations of LDL-c, more specifically small dense particles,11 is considered to be a marker of increased CVR in patients with hypertension, obesity and insulin resistance (or metabolic syndrome).9,10 The main problem with atherogenic dyslipidaemia is the quantification of small dense low density lipoproteins; this is why in clinical practice this diagnosis is based on raised levels of triglycerides (not particularly raised) and low levels of HDL-c (which denote the true nature of our profile in Latin America).

Although some cases of atherogenic dyslipidaemia are caused by genetic disorders (family hypercholesterolemia [FH], combined family hyperlipidaemia, genetic hypoalphalipoproteinemia), from 40% to 50% are secondary to preventable or modifiable conditions (dyslipidaemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus and smoking, etc.).

Statins are still the basic pillar of treatment for hypercholesterolemia, due to their proven efficacy in reducing LDL-c and mortality and the prevention of cardiovascular events.12–14 Nevertheless, some patients are intolerant of these drugs, while others do not achieve appropriate levels of LDL-c in spite of receiving optimum doses. This circumstances occurs the most often in patients at high or very high CVR and in those with statin intolerance.15 New lipid-modifying therapies (LMT) are now available in this context, including PCSK-9 inhibitors, which in general are indicated for the treatment of patients with high levels of cholesterol (e.g., patients with FH) or those at high CVR in spite of taking the maximum tolerated dose of statin and ezetimibe.16

The close relationship between cholesterol and the risk of coronary disease makes it necessary to evaluate the profile of dyslipidaemia cases in Colombia, with the purpose of promoting better healthcare policies, changing overall patient care and optimising the available therapeutic resources.

In Colombia the epidemiological data indicate that approximately 10% of the population aged from 18 to 69 years old have abnormal levels of total cholesterol,17 that ACVD is the main cause of disease, that ischaemic cardiopathy is the most frequent entity and is the cause of approximately 60% of the total mortality caused by ACVD.18 A study undertaken in 7 large cities in Latin America, including Bogotá, found a 14% prevalence of hypercholesterolaemia, together with incidences of arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome of 18%, 7% and 20%, respectively. More specifically, in Bogotá the estimated prevalence of dyslipidaemia amounted to 70% in men and 47.7% in women.19 Nevertheless, to date no study has covered a broad sample of the country that would make it possible to offer data on the distribution of different forms of dyslipidaemia and the usage pattern of LMT and the percentage of patients who achieve LDL-c targets, according to their CVR classification.

Material and methodsDesign and methodsThis study has a transversal and retrospective design, with the main aim of discovering the frequency of occurrence of different forms of dyslipidaemia (hypercholesterolaemia, hypertriglyceridaemia, low HDL-c, mixed dyslipidaemia and FH) in a broad sample of the Colombian population under treatment in high complexity centres (DYSIS-CO study). The secondary objectives of this study were: to estimate the frequency of cardiovascular comorbidities, to study statin and other LMT usage patterns, to discover the frequency of statin intolerance, to discover the percentage of patients who achieve LDL-c targets according to their CVR, to describe the percentage of patients with ACVD who do not achieve their LDL-c targets, and to estimate the distribution of CVR according to the Framingham scale adjusted for Colombia. Due to the retrospective nature of the study, genetic data were used when available to diagnose FH, or classification on the Dutch scale if available, or LDL-c levels above 190mg/dL, in the knowledge that they may be under-estimated.

PatientsSubjects older than 18 years old were included, with a diagnosis of dyslipidaemia according to the criteria set by the Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III,20 who had been followed-up during at least the previous 6 months and had been treated with a LMT during at least 3 months prior to the study. The patients with a history of acute coronary syndrome could be included independently of the duration of their treatment with LMT. The patients with an active neoplasm or those who had taken part in another clinical study were excluded from this study.

Procedures17 high complexity cardiovascular centres in Colombia were selected, based on the 6 geographical regions of the country and taking the population density of each one into account. The selected researchers were specialists in internal medicine, cardiology or endocrinology. Each participating centre included the first 25–30 consecutive patients who visited for a routine follow-up (throughout a specific period of 6 months) and who fulfilled the selection criteria. All of the patients gave their written consent prior to being included in the study.

The necessary clinical information was recorded during a single visit, including data from the medical interview as well as other retrospective data from clinical histories.

Statistical methodsThe size of the sample was 450 patients, assuming an exactitude error for the confidence interval of 95% of a proportion no higher than 5% and a value of 50% for one of the proportions. It was also assumed that data would be lacking for 15% of patients.

Descriptive statistical analysis of all of the variables included core tendency and dispersion measurements for the quantitative variables, and absolute and relative frequencies for the qualitative variables. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to study the distribution of the variables, using non-parametric methods of analysis when the data did not fulfil normalcy conditions. Confidence intervals were set at 95% and the level of significance of the statistical tests was set at 5% (bilateral). Statistical analysis was performed using version 9.4 of the SAS statistical package.

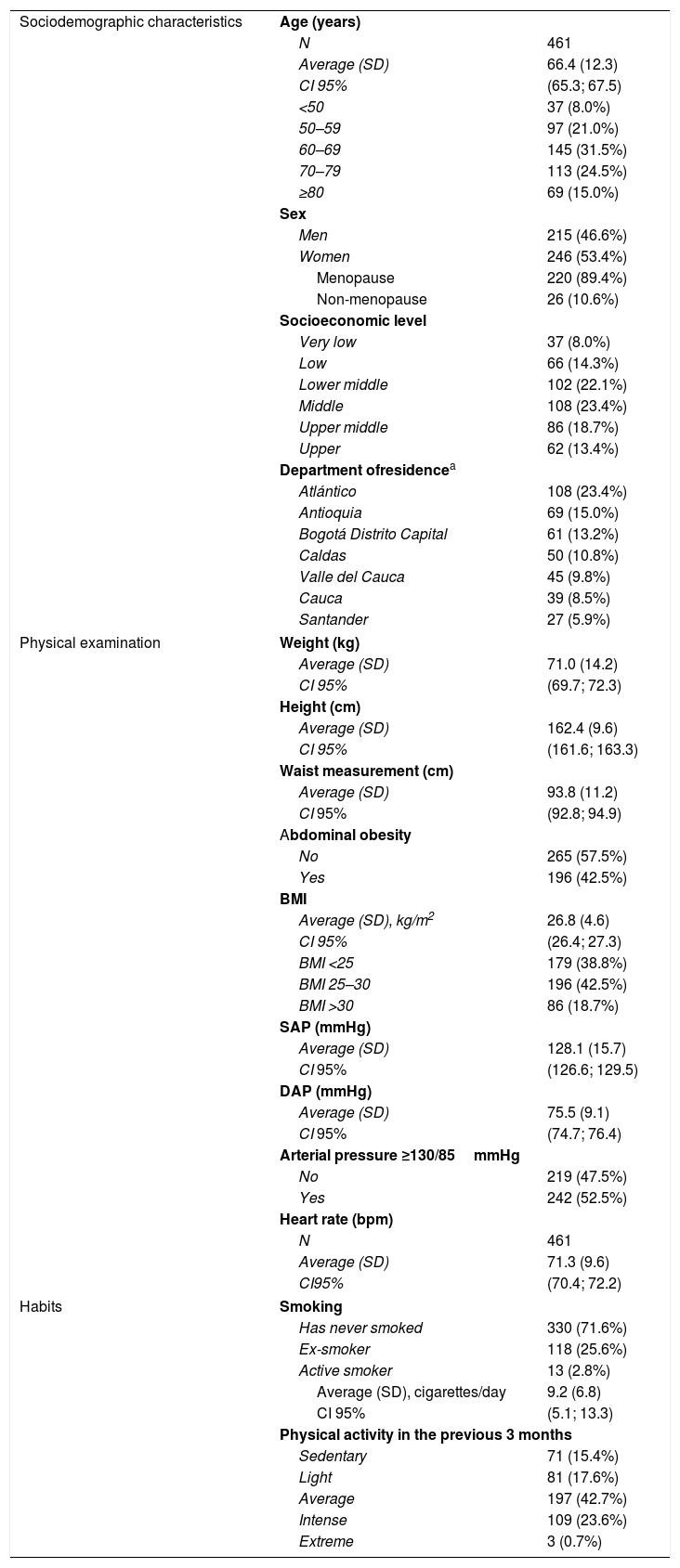

Results461 patients were included (246 women [53.4%]) with an average age (SD) of 66.4 (±12.3) years old. Approximately two thirds of the patients belonged to medium to low income groups. The patients mainly lived in the Atlántico, Antioquia and Bogotá Capital Departments. The demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Sociodemographic characteristics | Age (years) | |

| N | 461 | |

| Average (SD) | 66.4 (12.3) | |

| CI 95% | (65.3; 67.5) | |

| <50 | 37 (8.0%) | |

| 50–59 | 97 (21.0%) | |

| 60–69 | 145 (31.5%) | |

| 70–79 | 113 (24.5%) | |

| ≥80 | 69 (15.0%) | |

| Sex | ||

| Men | 215 (46.6%) | |

| Women | 246 (53.4%) | |

| Menopause | 220 (89.4%) | |

| Non-menopause | 26 (10.6%) | |

| Socioeconomic level | ||

| Very low | 37 (8.0%) | |

| Low | 66 (14.3%) | |

| Lower middle | 102 (22.1%) | |

| Middle | 108 (23.4%) | |

| Upper middle | 86 (18.7%) | |

| Upper | 62 (13.4%) | |

| Department ofresidencea | ||

| Atlántico | 108 (23.4%) | |

| Antioquia | 69 (15.0%) | |

| Bogotá Distrito Capital | 61 (13.2%) | |

| Caldas | 50 (10.8%) | |

| Valle del Cauca | 45 (9.8%) | |

| Cauca | 39 (8.5%) | |

| Santander | 27 (5.9%) | |

| Physical examination | Weight (kg) | |

| Average (SD) | 71.0 (14.2) | |

| CI 95% | (69.7; 72.3) | |

| Height (cm) | ||

| Average (SD) | 162.4 (9.6) | |

| CI 95% | (161.6; 163.3) | |

| Waist measurement (cm) | ||

| Average (SD) | 93.8 (11.2) | |

| CI 95% | (92.8; 94.9) | |

| Abdominal obesity | ||

| No | 265 (57.5%) | |

| Yes | 196 (42.5%) | |

| BMI | ||

| Average (SD), kg/m2 | 26.8 (4.6) | |

| CI 95% | (26.4; 27.3) | |

| BMI <25 | 179 (38.8%) | |

| BMI 25–30 | 196 (42.5%) | |

| BMI >30 | 86 (18.7%) | |

| SAP (mmHg) | ||

| Average (SD) | 128.1 (15.7) | |

| CI 95% | (126.6; 129.5) | |

| DAP (mmHg) | ||

| Average (SD) | 75.5 (9.1) | |

| CI 95% | (74.7; 76.4) | |

| Arterial pressure ≥130/85mmHg | ||

| No | 219 (47.5%) | |

| Yes | 242 (52.5%) | |

| Heart rate (bpm) | ||

| N | 461 | |

| Average (SD) | 71.3 (9.6) | |

| CI95% | (70.4; 72.2) | |

| Habits | Smoking | |

| Has never smoked | 330 (71.6%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 118 (25.6%) | |

| Active smoker | 13 (2.8%) | |

| Average (SD), cigarettes/day | 9.2 (6.8) | |

| CI 95% | (5.1; 13.3) | |

| Physical activity in the previous 3 months | ||

| Sedentary | 71 (15.4%) | |

| Light | 81 (17.6%) | |

| Average | 197 (42.7%) | |

| Intense | 109 (23.6%) | |

| Extreme | 3 (0.7%) | |

SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; SAP: systolic arterial pressure; DAS: diastolic arterial pressure.

62.2% of the patients were overweight or obese according to their body mass index (BMI) and 52.5% had high systolic or diastolic arterial pressure. A small number of patients were active smokers, and more than 65% of the total sample stated that their physical activity was average or greater (Table 1).

The most common comorbidities in the sample studied were: arterial hypertension (63.1%), cardiovascular diseases (40.6%), diabetes mellitus (27.5%), hypothyroidism (25.4%), arteriosclerosis (16.3%), chronic kidney disease (16.3%) and cerebral diseases (4.6%).

Distribution of dyslipidaemiasThe most common forms were mixed dyslipidaemia (51.4%, 237 patients) and hypercholesterolaemia (41.0%, 189 patients). The other forms of dyslipidaemia were in the minority (hypertriglyceridaemia: 5.4%; FH: 3.3% and low HDL-c: 0.7%).

A total of 140 patients (30.4%) had manifest ACVD, and of these 77 patients (55.0%) had hypercholesterolaemia, 56 (40.0%) had mixed dyslipidaemia, 3 patients (2.1%) had hypertriglyceridaemia, 2 (1.4%) had low HDL-c and 2 other patients (1.4%) had FH.

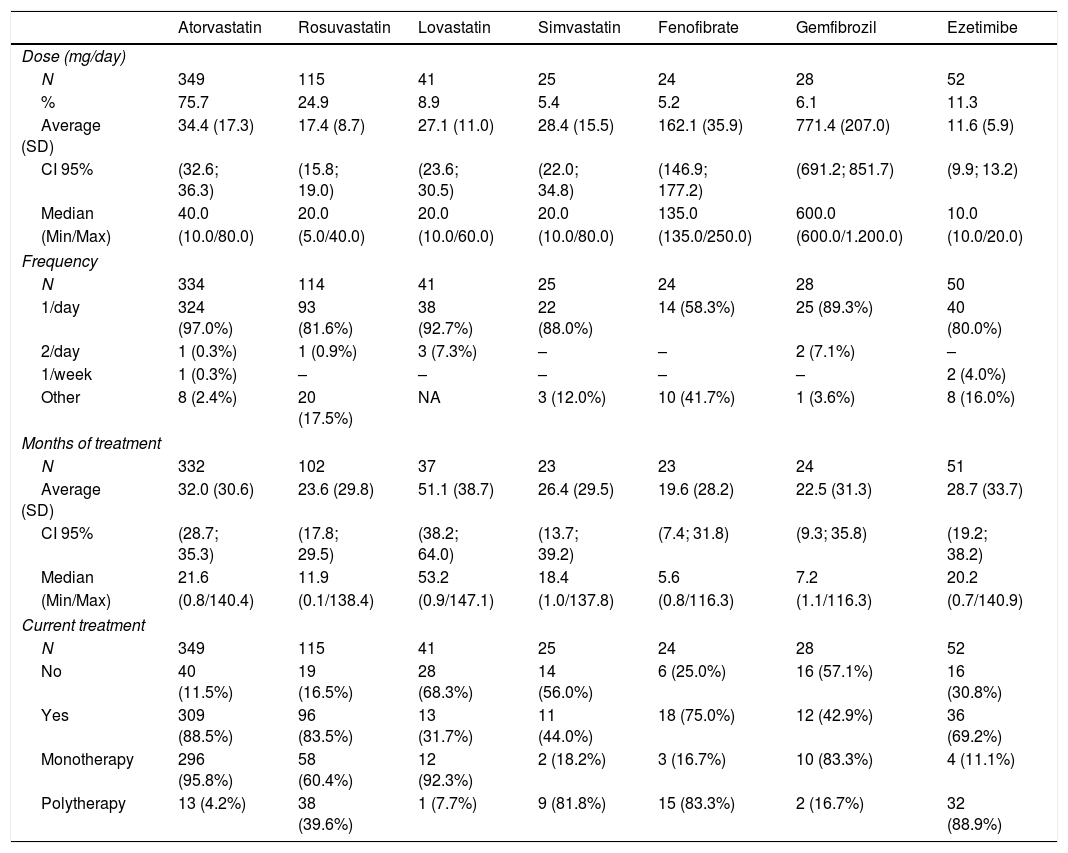

Lipid modifier therapiesThe average time from the start of treatment with LMT was 1.9 years (interquartile range 0.8–4.8). The most frequently prescribed drug was atorvastatin (75.7%), followed by rosuvastatin (24.9%), ezetimibe (11.3%), lovastatin (8.9%), gemfibrozil (6.1%), simvastatin (5.4%) and fenofibrate (5.2%). The majority of these LMT were administered as a monotherapy, except for simvastatin, fenofibrate and ezetimibe, which were used more frequently in combination with other drugs (Table 2). Only a minimum number of patients were treated using ciprofibrate and fenofibric acid, at 3.3% of patients in each case.

Pattern of lipid-modifying therapy use.

| Atorvastatin | Rosuvastatin | Lovastatin | Simvastatin | Fenofibrate | Gemfibrozil | Ezetimibe | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/day) | |||||||

| N | 349 | 115 | 41 | 25 | 24 | 28 | 52 |

| % | 75.7 | 24.9 | 8.9 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 6.1 | 11.3 |

| Average (SD) | 34.4 (17.3) | 17.4 (8.7) | 27.1 (11.0) | 28.4 (15.5) | 162.1 (35.9) | 771.4 (207.0) | 11.6 (5.9) |

| CI 95% | (32.6; 36.3) | (15.8; 19.0) | (23.6; 30.5) | (22.0; 34.8) | (146.9; 177.2) | (691.2; 851.7) | (9.9; 13.2) |

| Median | 40.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 20.0 | 135.0 | 600.0 | 10.0 |

| (Min/Max) | (10.0/80.0) | (5.0/40.0) | (10.0/60.0) | (10.0/80.0) | (135.0/250.0) | (600.0/1.200.0) | (10.0/20.0) |

| Frequency | |||||||

| N | 334 | 114 | 41 | 25 | 24 | 28 | 50 |

| 1/day | 324 (97.0%) | 93 (81.6%) | 38 (92.7%) | 22 (88.0%) | 14 (58.3%) | 25 (89.3%) | 40 (80.0%) |

| 2/day | 1 (0.3%) | 1 (0.9%) | 3 (7.3%) | – | – | 2 (7.1%) | – |

| 1/week | 1 (0.3%) | – | – | – | – | – | 2 (4.0%) |

| Other | 8 (2.4%) | 20 (17.5%) | NA | 3 (12.0%) | 10 (41.7%) | 1 (3.6%) | 8 (16.0%) |

| Months of treatment | |||||||

| N | 332 | 102 | 37 | 23 | 23 | 24 | 51 |

| Average (SD) | 32.0 (30.6) | 23.6 (29.8) | 51.1 (38.7) | 26.4 (29.5) | 19.6 (28.2) | 22.5 (31.3) | 28.7 (33.7) |

| CI 95% | (28.7; 35.3) | (17.8; 29.5) | (38.2; 64.0) | (13.7; 39.2) | (7.4; 31.8) | (9.3; 35.8) | (19.2; 38.2) |

| Median | 21.6 | 11.9 | 53.2 | 18.4 | 5.6 | 7.2 | 20.2 |

| (Min/Max) | (0.8/140.4) | (0.1/138.4) | (0.9/147.1) | (1.0/137.8) | (0.8/116.3) | (1.1/116.3) | (0.7/140.9) |

| Current treatment | |||||||

| N | 349 | 115 | 41 | 25 | 24 | 28 | 52 |

| No | 40 (11.5%) | 19 (16.5%) | 28 (68.3%) | 14 (56.0%) | 6 (25.0%) | 16 (57.1%) | 16 (30.8%) |

| Yes | 309 (88.5%) | 96 (83.5%) | 13 (31.7%) | 11 (44.0%) | 18 (75.0%) | 12 (42.9%) | 36 (69.2%) |

| Monotherapy | 296 (95.8%) | 58 (60.4%) | 12 (92.3%) | 2 (18.2%) | 3 (16.7%) | 10 (83.3%) | 4 (11.1%) |

| Polytherapy | 13 (4.2%) | 38 (39.6%) | 1 (7.7%) | 9 (81.8%) | 15 (83.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 32 (88.9%) |

SD: standard deviation; CI: confidence interval; NA: not applicable.

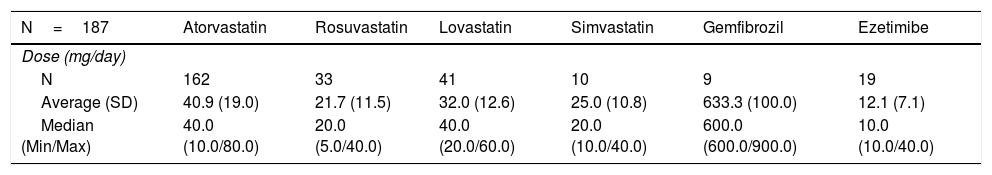

The average dose of statins was generally slightly higher in the subgroup of patients with coronary disease (Table 3).

Dose of lipid-modifying therapies in patients with coronary disease.

| N=187 | Atorvastatin | Rosuvastatin | Lovastatin | Simvastatin | Gemfibrozil | Ezetimibe |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dose (mg/day) | ||||||

| N | 162 | 33 | 41 | 10 | 9 | 19 |

| Average (SD) | 40.9 (19.0) | 21.7 (11.5) | 32.0 (12.6) | 25.0 (10.8) | 633.3 (100.0) | 12.1 (7.1) |

| Median (Min/Max) | 40.0 (10.0/80.0) | 20.0 (5.0/40.0) | 40.0 (20.0/60.0) | 20.0 (10.0/40.0) | 600.0 (600.0/900.0) | 10.0 (10.0/40.0) |

SD: standard deviation.

12.5% of the patients treated with fenofibrate mentioned adverse reactions associated with the treatment, as did 5.2% of those treated with atorvastatin, 4.3% in the case of rosuvastatin, 4.0% with simvastatin and 3.8% of those treated with ezetimibe. The adverse reactions recorded were included in those described in the safety profiles of the drugs. The frequency of adverse reactions to statins reported varied from 5.2% (atorvastatin) to 4.0% (simvastatin), and the most frequent was myalgia, followed by raised CPK, raised ALT and gastritis. 2.6% of patients were intolerant of statins. 3.8% of those patients treated with ezetimibe reported adverse reactions, the most common of which were raised ALT and CPK. Lastly, adverse reactions to fenofibrate were reported by 12.5% of the patients who received it, and in all cases they consisted of raised CPK.

Evolution of dyslipidaemia casesTreatment with LMT resulted in an improvement in lipid parameters. Thus total cholesterol levels fell by an average of 45.1mg/dL (CI 95% −51.8; −38.4) in comparison with those prior to starting treatment (P<.0001). The average most recent LDL-c was 96.2mg/dL (CI 95% 92.4; 100.0).

Similarly, levels of triglycerides, non-HDL cholesterol and LDL-c fell by an average of 48.2mg/dL (CI 95% −64.3; −32.2; P<.0001), 47.8mg/dL (CI 95% −54.7; −40.8; P<.0001) and 38.1mg/dL (CI 95% −44.1; −32.0; P<.0001), respectively. HDL-c rose by an average of 1.6mg/dL (CI 95% 0.3; 2.9; P=.0135). In the patient subgroup with manifest ACVD, total cholesterol levels fell by an average of 35.2mg/dL (CI 95% −44.7; −25.7) in comparison with levels prior to starting treatment (P<.0001). The average fall in LDL-c was 27.2mg/dL (CI 95% −36.2; −18.2; P<.0001) and triglycerides and non-HDL cholesterol fell by an average of 27.0mg/dL (CI 95% −48.7; −5.4; P=.002) and 36.7mg/dL (CI 95% −46.4; −27.1; P<.0001), respectively. HDL-c levels did not change significantly (with an average change of 0.7mg/dL [CI 95% −1.1; 2.4; P=.4619]).

Cardiovascular riskOf the total sample, 92 patients (25.7%) had a history of acute myocardial infarct, 86 (26.9%) had needed coronary revascularisation (percutaneous or surgical), 56 (15.6%) had had an acute coronary syndrome and 8 patients (1.7%) had unstable angina.

CVR was calculated on the Framingham scale adjusted for the Colombian population. The average risk level before the start of LMT was 4.9 (CI 95% 4.4; 5.4), distributed according to category in the following way: 286 patients (89.4%) were at low risk (<10%), 33 patients (10.3%) were at intermediate risk (10–20%) and one patient (0.3%) was at high risk (>20%).

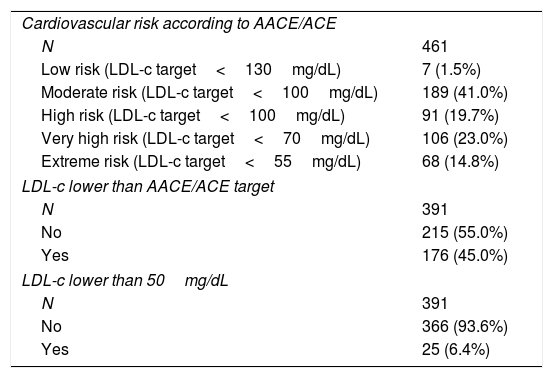

The CVR of the sample was also evaluated by applying AACE/ACE (American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology) criteria. Fewer than half of the patients in the total sample had achieved LDL-c targets suitable for their risk level (Table 4). In the case of the patients with coronary disease under treatment with the maximum dose of statins, 28.6% (10 patients) had not achieved the target LDL-c appropriate for their level of risk.

Cardiovascular risk according to AACE/ACE criteria and patients who achieved the different LDL-c targets (total sample).

| Cardiovascular risk according to AACE/ACE | |

| N | 461 |

| Low risk (LDL-c target<130mg/dL) | 7 (1.5%) |

| Moderate risk (LDL-c target<100mg/dL) | 189 (41.0%) |

| High risk (LDL-c target<100mg/dL) | 91 (19.7%) |

| Very high risk (LDL-c target<70mg/dL) | 106 (23.0%) |

| Extreme risk (LDL-c target<55mg/dL) | 68 (14.8%) |

| LDL-c lower than AACE/ACE target | |

| N | 391 |

| No | 215 (55.0%) |

| Yes | 176 (45.0%) |

| LDL-c lower than 50mg/dL | |

| N | 391 |

| No | 366 (93.6%) |

| Yes | 25 (6.4%) |

AACE/ACE: American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology; LDL-c: cholesterol bound to low density lipoproteins.

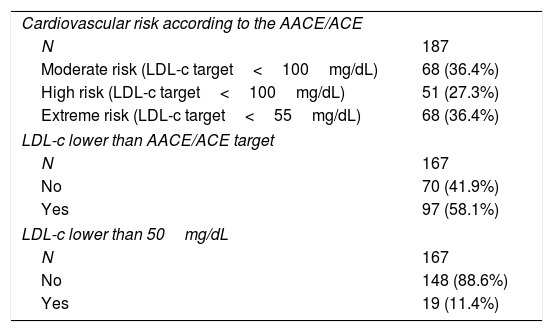

In the subgroup of patients with ACVD, 4 of every 10 patients did not achieve their specific LDL-c targets and two thirds of them were within the high and extreme risk categories (Table 5). In the case of the patients with coronary disease who were under treatment with statins at the maximum dose, 28.6% (10 patients) had not achieved the appropriate LDL-c target for their risk level.

Cardiovascular risk according to AACE/ACE criteria and patients who achieved the different LDL-c targets (patient subgroups with ACVD).

| Cardiovascular risk according to the AACE/ACE | |

| N | 187 |

| Moderate risk (LDL-c target<100mg/dL) | 68 (36.4%) |

| High risk (LDL-c target<100mg/dL) | 51 (27.3%) |

| Extreme risk (LDL-c target<55mg/dL) | 68 (36.4%) |

| LDL-c lower than AACE/ACE target | |

| N | 167 |

| No | 70 (41.9%) |

| Yes | 97 (58.1%) |

| LDL-c lower than 50mg/dL | |

| N | 167 |

| No | 148 (88.6%) |

| Yes | 19 (11.4%) |

AACE/ACE: American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American College of Endocrinology; LDL-c: cholesterol bound to low density lipoproteins; ACVD: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease.

This study shows the frequency and distribution of dyslipidaemia in Colombia. It may be considered to be representative as it includes a broad population, and as well as covering the 6 main geographical areas of the country, it also reflects their economic heterogeneity. The results obtained show that the most common forms of dyslipidaemia in the evaluated population are mixed dyslipidaemia and hypercholesterolaemia. Although few similar epidemiological studies have been conducted at a local level, a study on the prevalence of CVR factors in patients with dyslipidaemia in Colombia also found that mixed dyslipidaemia and hypercholesterolaemia were the most common forms of dyslipidaemia.21 However, these data contrast with those obtained in neighbouring countries, such as Venezuela, where a recent study showed that mixed dyslipidaemia is the least frequent form in the population studied.22 In any case, the high incidence of hypercholesterolaemia is a constant in our country and other adjacent countries, as it is in other regions of the world such as Spain.23,24

The data on the incidence of FH deserve particular mention. To date, for this type of dyslipidaemia, the only data available for Colombia were obtained by extrapolation, according to which the prevalence in the general population stood at around 0.6%.25,26 Nevertheless, the results of the DYSIS-CO study have shown that the incidence of FH stands at 3.3% in the population diagnosed with dyslipidaemia, meaning that the incidence is almost six times higher than that in the general population. Given that patients with FH are per se a population at very high CVR, this datum should be taken into account in clinical practice, to monitor these patients more closely and modify therapeutic practice if objectives for their level of risk are not attained.

In fact, this study shows that a high percentage of patients under treatment with LMT do not achieve their LDL-c target levels. Although it was not possible to calculate specifically for the FH subgroup due to insufficient sample size, 55% of the total number of patients included were above their LDL-c individual-risk-adapted target levels. This was so in spite of the fact that the treatment they received had reduced LDL-c concentrations by 19.2% and the duplication of the percentage of patients with LDL-c<100mg/dL. It is worthwhile underlining the greater impact that this aspect has in the specific case of patients with previous ACVD, given that somewhat more than 40% did not achieve their specific objective for LDL-c. Achieving LDL-c levels below the target level depending on the CVR of each patient becomes of capital importance when it is taken into account that, in our study, a high percentage of patients have cardiovascular comorbidities and that, after the evidence obtained with statins, long-term clinical experiments undertaken afterwards with different molecules (ezetimibe and PCSK-9 inhibitors) have consistently shown that additional reductions in LDL-c are associated with correlated reductions in CVR.27–29 This finding may be related to observations respecting therapeutic management, as the average doses of statins used in patients correspond to moderately intense therapies. Even in the subgroup of patients with coronary disease, who are now considered to be at very high or extreme CVR,30 the average doses of statins are only slightly higher, with a broad margin for increase within the high intensity therapy (atorvastatin 40–80mg; rosuvastatin 20–40mg) recommended for patients at higher CVR.31 Furthermore, even among those patients who receive maximum doses of statins, according to our study 28% do not achieve their LDL-c target. These results show that patients with dyslipidaemia are not sufficiently controlled, and that therefore: (a) treatment with statins needs to be optimised in patients in which it is possible to intensify treatment, and (b) there is a need to consider new treatments in patients at high CVR who are insufficiently controlled with optimum doses of statins.

One of the known causes which prevent increasing the dosage of statins is the development of patient intolerance. Incidences of statin intolerance have been reported of up to 29% in observational studies, although the figures vary very widely from one study to another.32 The frequency obtained in our study (2.6%) is clearly lower, although this does not mean that it is insignificant. Statin intolerance influences the dose that is actually given to patients, and it has been shown to be an independent factor associated with failure to meet LDL-c targets.33 Additionally, given that there is no clear consensus on the definition of this adverse effect, and that no diagnostic test for it is available because of its important subjective component, it cannot be ruled out that the incidence found in this study really is an underestimate.

A study undertaken in a rural population in Colombia33 in subjects aged from 35 to 70 years old showed a high incidence of dyslipidaemia (87.7% in the 6628 subjects studied); the most common alteration was raised non-HDL cholesterol (75.3%), followed by low HDL-c (57.1%), hypertriglyceridaemia (49.7%) and total hypercholesterolaemia (48.5%). Previous studies34–38 reported rates of prevalence in Colombia that varied from 15.7% to 73.8%. Atherogenic dyslipidaemia in Latin America is a therapeutic challenge, and this is associated with many socioeconomic and cultural aspects. These include physical activity and a sedentary lifestyle, dietary customs of consuming fats and sugars, and of course the genetic and epigenetic components.39

ConclusionsThis study shows a representative distribution of forms of dyslipidaemia treated in high complexity centres in Colombia as well as their associated CVR. It shows that some patients, including those treated with the maximum tolerated dose of statins and, when possible, using combined therapies with ezetimibe, do not achieve the LDL-c targets corresponding to their CVR level. This would mean that in practice these patients may require intensified treatment with statins, or combinations with other additional therapies to achieve their LDL-c targets and improve their CVR. Although the descriptive and retrospective nature of this study makes it impossible to establish causal explanations for some of its findings, as these would require a different type of study, it would be positive if these results facilitate and promote health policies and the optimum distribution of the resources that are necessary to achieve better control of hypercholesterolaemia and cardiovascular risk.

FinancingThis study was financed by Sanofi – Colombia.

Conflict of interestsSanofi took part in the design of this study as well as data gathering and analysis. However, it did not take part in preparing the manuscript or the decision to send it for publication. The authors had complete access to all of the data in this study, and they accept full responsibility for the integrity of its data and the exactitude of data analysis. The authors Etna L. Valenzuela and Mónica Betancur are Sanofi employees.

We would like to thank the SAIL team for their help in data analysis and manuscript preparation.

Please cite this article as: Ruiz ÁJ, Vargas-Uricoechea H, Urina-Triana M, Román-González A, Isaza D, Etayo E, et al. Las dislipidemias y su tratamiento en centros de alta complejidad en Colombia. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2020;32:101–110.