To evaluate presence of risk factors for cardiovascular diseases (CVD) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) in a group of health care workers.

MethodsDuring the X Latin American Congress of Internal Medicine held in August 2017, in Cartagena, Colombia, attendees were invited to participate in the study that included a survey on medical, pharmacological and family history, lifestyle habits, blood pressure measurement, anthropometry, muscle strength and laboratory studies. The INTERHEART and FINDRISC scales were used to calculate the risk of CVD and diabetes, respectively.

ResultsAmong 186 participants with an average age of 37.9 years, 94% physicians (52.7% specialists), the prevalence of hypertension was 20.4%, overweight 40.3%, obesity 19.9%, and dyslipidemia 67.3%. 20.9% were current smokers or had smoked, and 60.8% were sedentary. Hypertensive patients were found to be older, had higher BMI, higher waist circumference, higher waist-to-hip ratio, higher of body fat and visceral fat, smoked more and had lower muscle strength (high jump: 0.38 vs 0.42 cm; p = 0.01). In 44.3% of participants was observed a high-risk score for CVD. The prevalence of diabetes was 6.59% and 27.7% were at risk.

ConclusionThe prevalence of risk factors for CVD among the Latin American physicians studied was similar to that reported in the general population. The prevalence of high-risk scores for CVD and DM2 was high and healthy lifestyle habits were low. It is necessary to improve adherence to healthy lifestyles among these physicians in charge of controlling these factors in the general population.

Evaluar la presencia de factores de riesgo para enfermedades cardiovasculares (ECV) y diabetes mellitus tipo 2 (DM2) en un grupo de trabajadores de la salud.

MétodosDurante el X Congreso Latinoamericano de Medicina Interna realizado en agosto del 2017, en Cartagena, Colombia, se invitó a los asistentes a participar del estudio que incluyó encuesta sobre antecedentes médicos, farmacológicos, familiares, hábitos de vida, medición de presión arterial, antropometría, fuerza muscular y laboratorios. Se utilizó las escalas INTERHEART y FINDRISC para calcular el riesgo de ECV y diabetes.

ResultadosEn 186 participantes con edad promedio de 37,9 años, 94% médicos (52,7% especialistas) la prevalencia de hipertensión fue 20,4%, sobrepeso 40,3%, obesidad 19,9% y dislipidemia 67,3%. El 20,9% eran fumadores actuales o habían fumado, y 60,8% eran sedentarios. Los hipertensos tuvieron mayor edad, IMC, circunferencia de cintura, relación cintura/cadera, porcentaje de grasa corporal, grasa visceral, fueron más fumadores y tuvieron menor fuerza muscular (salto alto: 0,38 vs 0,42 cm; p = 0.01). El 44,3% presentaron riesgo cardiovascular alto. La prevalencia de diabetes fue 6,59% y 27,7% estaban en riesgo.

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de factores de riesgo para ECV entre los médicos Latinoamericanos estudiados fue similar a la reportada en la población general. La prevalencia de puntuación de alto riesgo para ECV y DM2 fue alta y los hábitos de vida saludables fueron bajos. Es necesario mejorar la adherencia a estilos de vida saludable entre estos médicos encargados del control de esos factores en la población general.

The leading causes of death worldwide according to World Health Organization (WHO) reports are acute myocardial infarction (AMI) and cerebrovascular accident (CVA).1 The INTERHEART2 and INTERSTROKE3 studies identified modifiable risk factors for AMI and stroke (hypertension, abdominal obesity, smoking, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemia, depression, anxiety, low fruit and vegetable intake, and lack of exercise). In Latin America, hypertension (HT) is particularly relevant, given its elevated prevalence, affecting more than 50% of all people over the age of 35 years.4–7

Health professionals are key to the implementation of strategies for education, information, prevention, and control of cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors8–10; however, in Latin America, little is known about the prevalence of these factors and adherence to healthy lifestyle recommendations in members of the health care team.11–14 Consequently, this study sought to assess the presence of risk factors for CVD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2) in a group of health care workers attending a medical conference where these topics were discussed.

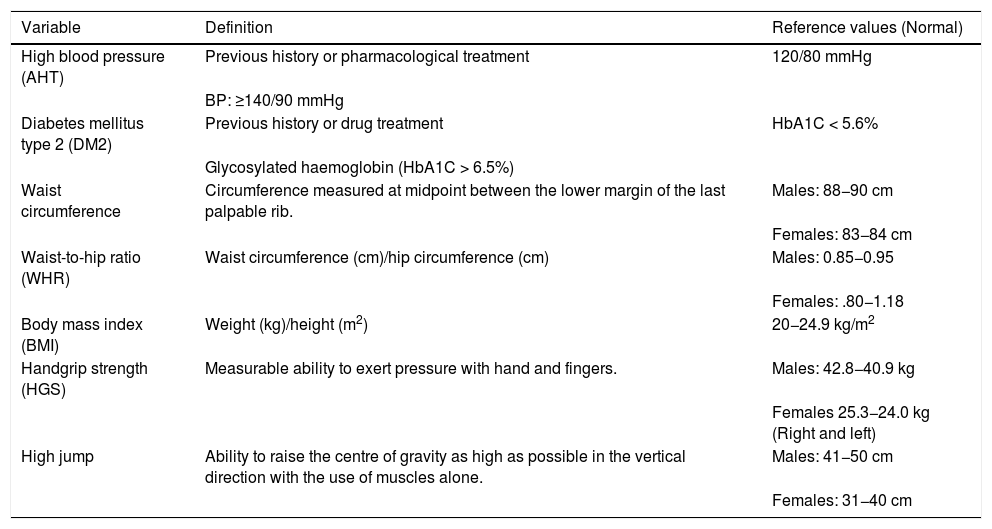

Material and methodObservational, descriptive, cross-sectional study endorsed by the Latin American Society of Internal Medicine (SOLAMI) within the framework of the X Latin American Congress of Internal Medicine held in August 2017, in the city of Cartagena, Colombia. All attendees were invited to participate freely and voluntarily. Six care stations were set up during the four days the conference lasted, with both medical and nursing staff. At the first station, a verbal consent report was obtained and questions were asked about personal and family medical and pharmacological history, and about healthy lifestyle habits. At the second station, blood pressure was taken. This was the only measurement that needed to be taken prior to going through the other stations. At the third station, body composition measurements were recorded. Anthropometric measurements were collected at the fourth station. At the fifth station, grip strength was taken and noted. At the sixth station, a capillary blood sample was taken to determine total cholesterol, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, random glucose, and glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c). Table 1 summarizes the definition and reference values of the main variables to be used.

Overview of key variables.

| Variable | Definition | Reference values (Normal) |

|---|---|---|

| High blood pressure (AHT) | Previous history or pharmacological treatment | 120/80 mmHg |

| BP: ≥140/90 mmHg | ||

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 (DM2) | Previous history or drug treatment | HbA1C < 5.6% |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1C > 6.5%) | ||

| Waist circumference | Circumference measured at midpoint between the lower margin of the last palpable rib. | Males: 88−90 cm |

| Females: 83−84 cm | ||

| Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) | Waist circumference (cm)/hip circumference (cm) | Males: 0.85−0.95 |

| Females: .80−1.18 | ||

| Body mass index (BMI) | Weight (kg)/height (m2) | 20−24.9 kg/m2 |

| Handgrip strength (HGS) | Measurable ability to exert pressure with hand and fingers. | Males: 42.8−40.9 kg |

| Females 25.3−24.0 kg (Right and left) | ||

| High jump | Ability to raise the centre of gravity as high as possible in the vertical direction with the use of muscles alone. | Males: 41−50 cm |

| Females: 31−40 cm |

Blood pressure was measured with the participant at rest for at least five minutes, using a digital oscillometer (Omron® HEM-7220) with the right arm resting on a stable surface, at heart level, on three occasions with two-minute intervals between each measurement. The average of the three measurements was used for statistical analysis. The anthropometric measurements obtained were weight, height, waist circumference, and hip circumference, which were used to calculate the waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) and body mass index (BMI).

Waist circumference was measured midway between the lower margin of the last palpable rib and the top of the iliac crest, using a stretch-resistant tape measure; the normal value reported for the South American population in men is 88−90 cm and 83−84 cm in women. Hip circumference was measured around the widest part of the buttocks, with the tape measure parallel to the floor. WHR was obtained by dividing the waist circumference by the hip circumference, with both values reported in centimetres. The reported normal value of the WHR in the South American population is 0.85−0.95 in men and 0.80−1.18 in women.15–17

The reference values for defining obesity and overweight according to BMI are the ones recommended by the WHO; a BMI of 18.5−20 kg/m2 is normal; overweight BMI is 25−29.9 kg/m2, and obesity BMI > 30 kg/m2.15–17 An electric bioimpedance scale (Tanita® IRONMAN BC-554) was used for body composition and weight measurements, which reported weight in kilograms, body fat as a percentage, muscle mass in kilograms, and visceral fat as a percentage.

Muscle strength is the ability of a muscle or muscle group to produce force against external resistance18 and its decrease, particularly in the upper body, has been postulated as a new risk marker for cardiovascular disease.35 Using a hand-held dynamometer (Jamar® hydraulic model 5030J1), upper body muscle strength was evaluated by means of handgrip strength (HGS), which is the quantifiable ability to exert pressure with the hand and fingers19; handgrip-peak strength, and age-adjusted handgrip strength. Three measurements were taken for each hand and an average was obtained; peak grip strength refers to the best measurement. The grip strength was also adjusted for weight. The average results reported in several studies conducted in the Colombian population for men have been 42.8 kg and 40.9 kg for HGS on the right and left, respectively; while for women, the averages have been 25.3 kg and 24.0 kg, respectively.20 Lower segment muscle strength was appraised by means of the high jump. The high jump is the ability to lift the centre of gravity as high as possible in the vertical direction solely with the use of one’s own muscles.21 Average values have been reported for men as being between 41 and 50 cm and for women, between 31 and 40 cm.22 This measurement of muscle strength is expressed in centimetres and calculated using the ForceDecks platform (VALD Performance, United Kingdom) designed by one of the authors (DDC), for which participants were asked to perform a vertical jump from the floor as high as possible.

HTN was defined when the participant reported a history of hypertension for which they were taking antihypertensive medication or when their recorded blood pressure was ≥140/90 mmHg. DM2 was designated when the person reported being diabetic and taking hypoglycaemic medication, or had a glycosylated haemoglobin ≥6.5%. To calculate the risk of developing DM2, the FINDRISC scale was administered, which in Colombia has demonstrated 74% sensitivity and 60% specificity to categorise the population having no risk (<12 points) and at risk (≥12 points).23 The lipid profile was assessed, defining atherogenic dyslipidaemia as the presence of triglycerides ≥150 mg/dL, LDL-cholesterol 130 mg/dL, and HDL-cholesterol <40 mg/dL in men and <50 mg/dL in women. The Accutrend® Plus kit (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany), which is validated for use,24,25 was used for biochemical determination.24,25 Twenty-seven and 26 persons were excluded from the sample for dyslipidaemia and diabetes, respectively, because they failed to consent to have this variable recorded, as they felt it to be invasive. The risk of cardiovascular disease was calculated according to the INTERHEART questionnaire, taking a score equal to or greater than 10 points (highest tertile) as the significant risk cut-off value, which in a previous population-based study was associated with a 5.7-fold increase in the probability of AMI compared to a score of 0–4 (lowest tertile).26,27

Statistical analysis was performed using the STATA VE 11.2 software (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA). Categorical variables are summarised with absolute and relative frequencies; frequency measures are presented with their 95% confidence interval. For quantitative variables, measures of central tendency and dispersion were estimated according to frequency distribution. The independence of the explanatory variables and the presence of HTN was assessed with χ2 or Fischer’s exact test, depending on the number of observations per category. The relationship of anthropometric, body composition, physical fitness, and metabolic control measures and the presence of HTN was analysed with Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test according to the frequency distribution. The significance level of the study was 5%.

ResultsOf the 186 participants, 101 (54.3%) were male and the mean sample age was 37.9 ± 14.7 years (range: 18–80 years). Physicians accounted for 175 of the participants (94%), 98 (52.7%) of whom were specialists in internal medicine and the other 77 (41.4%) were primary care physicians; the remaining 5.9% included nurses and medical students. Thirty-nine (20.9%) had formerly smoked or were current smokers; 113 (60.8%) reported being sedentary. Mean BMI was 26.5 ± 4.5 kg/m2 (range: 15.5–41.9 kg/m2) and mean waist circumference was 87.9 ± 13.1 cm (range: 63.4−126 cm), with a mean of 79.3 cm in women and 95.2 cm in men.

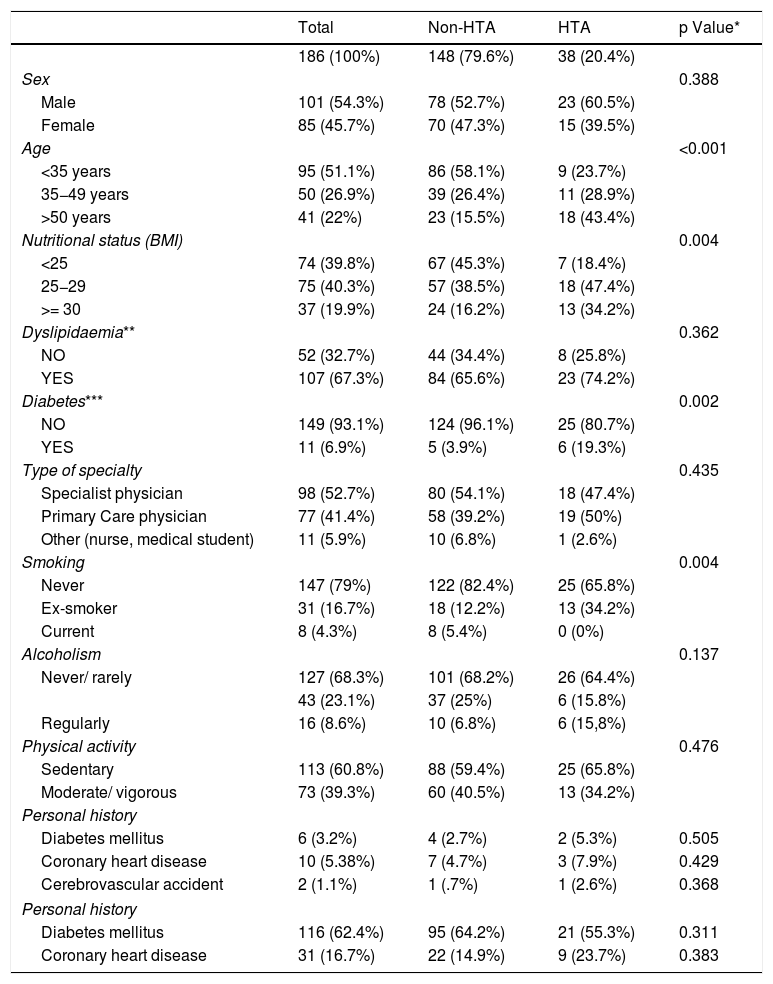

AHT prevalence was 20.43% [95% CI: 14.6–26.3%]; age (p < 0.001) and smoking (p = 0.004) were seen to be the two main driving factors behind it (Table 1). The prevalence of overweight (BMI > 25–30) was 40.32% [95% CI: 33.20–47.4%] and for obesity (BMI > 30) it was 19.89% [95% CI: 14.1–25.68%]. Atherogenic dyslipidaemia was exhibited by 67.5% [95% CI: 60.3–74.7%] of the participants.

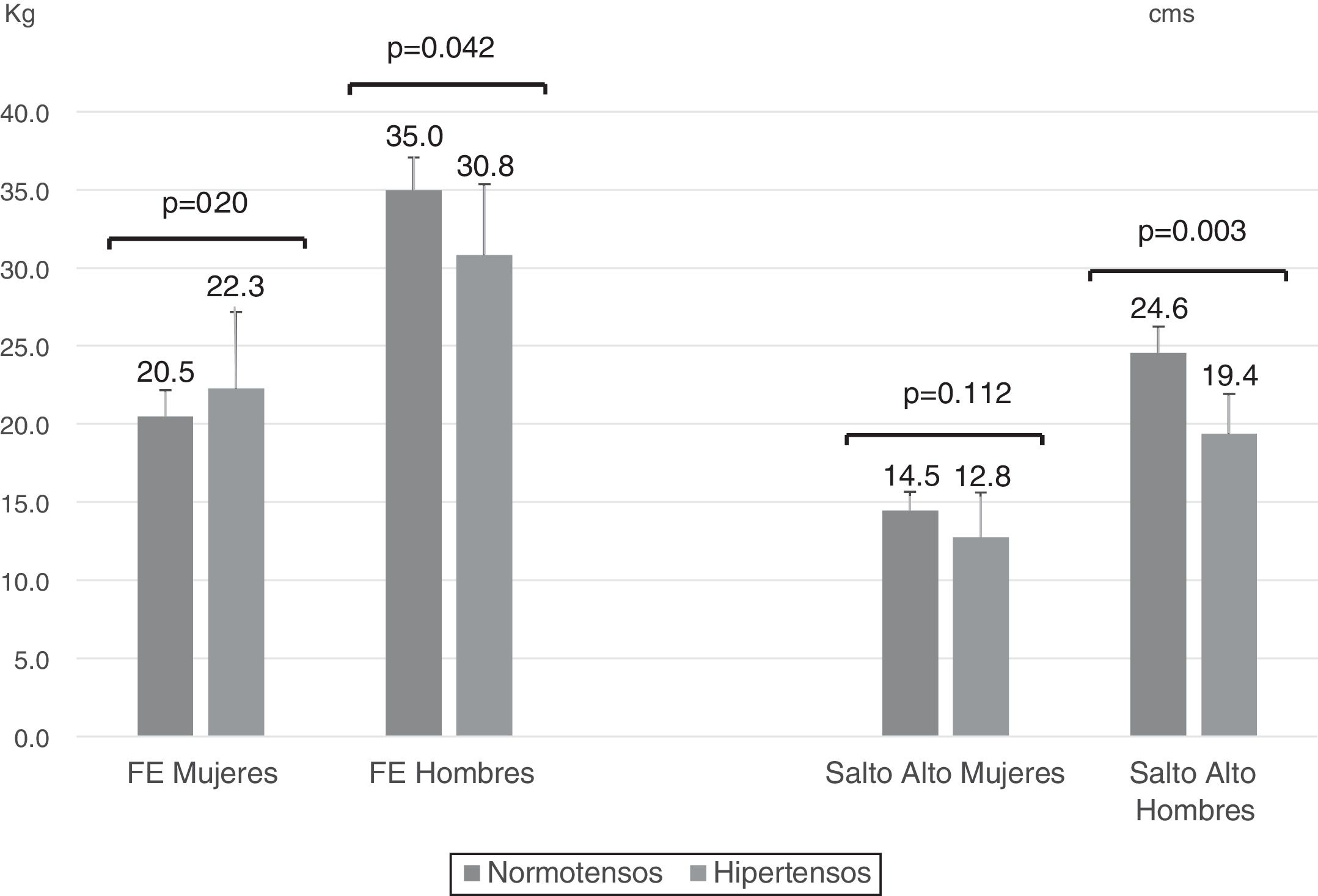

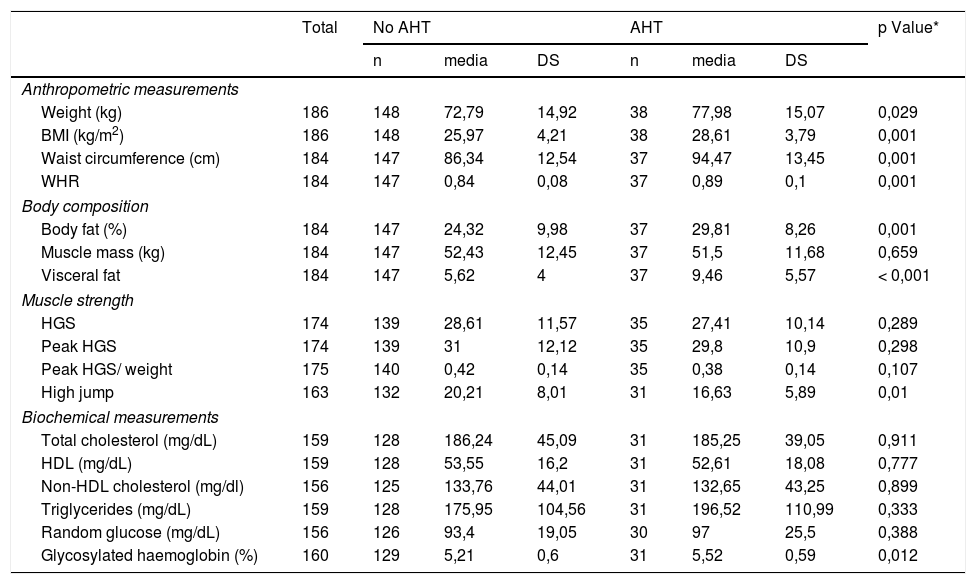

Table 2 shows the anthropometric characteristics, muscle strength, and biochemical test results according to the presence or absence of hypertension. Those with hypertension were significantly heavier, had a significantly higher BMI, larger waist circumference, waist/hip ratio, and higher percentages of body and visceral fat. Muscle strength tended to be lower in the hypertensive group. High jump results achieved levels of statistical significance in the hypertensive group. There were no differences in biochemical determinations, with the exception of glycosylated haemoglobin which was higher in hypertensive individuals (Table 3).

Population characteristics.

| Total | Non-HTA | HTA | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 186 (100%) | 148 (79.6%) | 38 (20.4%) | ||

| Sex | 0.388 | |||

| Male | 101 (54.3%) | 78 (52.7%) | 23 (60.5%) | |

| Female | 85 (45.7%) | 70 (47.3%) | 15 (39.5%) | |

| Age | <0.001 | |||

| <35 years | 95 (51.1%) | 86 (58.1%) | 9 (23.7%) | |

| 35−49 years | 50 (26.9%) | 39 (26.4%) | 11 (28.9%) | |

| >50 years | 41 (22%) | 23 (15.5%) | 18 (43.4%) | |

| Nutritional status (BMI) | 0.004 | |||

| <25 | 74 (39.8%) | 67 (45.3%) | 7 (18.4%) | |

| 25−29 | 75 (40.3%) | 57 (38.5%) | 18 (47.4%) | |

| >= 30 | 37 (19.9%) | 24 (16.2%) | 13 (34.2%) | |

| Dyslipidaemia** | 0.362 | |||

| NO | 52 (32.7%) | 44 (34.4%) | 8 (25.8%) | |

| YES | 107 (67.3%) | 84 (65.6%) | 23 (74.2%) | |

| Diabetes*** | 0.002 | |||

| NO | 149 (93.1%) | 124 (96.1%) | 25 (80.7%) | |

| YES | 11 (6.9%) | 5 (3.9%) | 6 (19.3%) | |

| Type of specialty | 0.435 | |||

| Specialist physician | 98 (52.7%) | 80 (54.1%) | 18 (47.4%) | |

| Primary Care physician | 77 (41.4%) | 58 (39.2%) | 19 (50%) | |

| Other (nurse, medical student) | 11 (5.9%) | 10 (6.8%) | 1 (2.6%) | |

| Smoking | 0.004 | |||

| Never | 147 (79%) | 122 (82.4%) | 25 (65.8%) | |

| Ex-smoker | 31 (16.7%) | 18 (12.2%) | 13 (34.2%) | |

| Current | 8 (4.3%) | 8 (5.4%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Alcoholism | 0.137 | |||

| Never/ rarely | 127 (68.3%) | 101 (68.2%) | 26 (64.4%) | |

| 43 (23.1%) | 37 (25%) | 6 (15.8%) | ||

| Regularly | 16 (8.6%) | 10 (6.8%) | 6 (15,8%) | |

| Physical activity | 0.476 | |||

| Sedentary | 113 (60.8%) | 88 (59.4%) | 25 (65.8%) | |

| Moderate/ vigorous | 73 (39.3%) | 60 (40.5%) | 13 (34.2%) | |

| Personal history | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 6 (3.2%) | 4 (2.7%) | 2 (5.3%) | 0.505 |

| Coronary heart disease | 10 (5.38%) | 7 (4.7%) | 3 (7.9%) | 0.429 |

| Cerebrovascular accident | 2 (1.1%) | 1 (.7%) | 1 (2.6%) | 0.368 |

| Personal history | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 116 (62.4%) | 95 (64.2%) | 21 (55.3%) | 0.311 |

| Coronary heart disease | 31 (16.7%) | 22 (14.9%) | 9 (23.7%) | 0.383 |

Anthropometric measurements, body composition, physical fitness, and biochemical measurements between hypertensive and non-hypertensive participants.

| Total | No AHT | AHT | p Value* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | media | DS | n | media | DS | |||

| Anthropometric measurements | ||||||||

| Weight (kg) | 186 | 148 | 72,79 | 14,92 | 38 | 77,98 | 15,07 | 0,029 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 186 | 148 | 25,97 | 4,21 | 38 | 28,61 | 3,79 | 0,001 |

| Waist circumference (cm) | 184 | 147 | 86,34 | 12,54 | 37 | 94,47 | 13,45 | 0,001 |

| WHR | 184 | 147 | 0,84 | 0,08 | 37 | 0,89 | 0,1 | 0,001 |

| Body composition | ||||||||

| Body fat (%) | 184 | 147 | 24,32 | 9,98 | 37 | 29,81 | 8,26 | 0,001 |

| Muscle mass (kg) | 184 | 147 | 52,43 | 12,45 | 37 | 51,5 | 11,68 | 0,659 |

| Visceral fat | 184 | 147 | 5,62 | 4 | 37 | 9,46 | 5,57 | < 0,001 |

| Muscle strength | ||||||||

| HGS | 174 | 139 | 28,61 | 11,57 | 35 | 27,41 | 10,14 | 0,289 |

| Peak HGS | 174 | 139 | 31 | 12,12 | 35 | 29,8 | 10,9 | 0,298 |

| Peak HGS/ weight | 175 | 140 | 0,42 | 0,14 | 35 | 0,38 | 0,14 | 0,107 |

| High jump | 163 | 132 | 20,21 | 8,01 | 31 | 16,63 | 5,89 | 0,01 |

| Biochemical measurements | ||||||||

| Total cholesterol (mg/dL) | 159 | 128 | 186,24 | 45,09 | 31 | 185,25 | 39,05 | 0,911 |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 159 | 128 | 53,55 | 16,2 | 31 | 52,61 | 18,08 | 0,777 |

| Non-HDL cholesterol (mg/dl) | 156 | 125 | 133,76 | 44,01 | 31 | 132,65 | 43,25 | 0,899 |

| Triglycerides (mg/dL) | 159 | 128 | 175,95 | 104,56 | 31 | 196,52 | 110,99 | 0,333 |

| Random glucose (mg/dL) | 156 | 126 | 93,4 | 19,05 | 30 | 97 | 25,5 | 0,388 |

| Glycosylated haemoglobin (%) | 160 | 129 | 5,21 | 0,6 | 31 | 5,52 | 0,59 | 0,012 |

HGS: hand grip strength; AHT: arterial hypertension; BMI: body mass index; WHR: waist/ hip ratio.

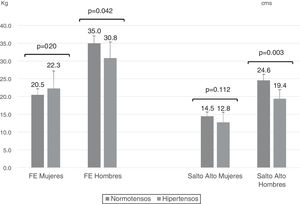

When analysing strength parameters according to sex, men with HTN were found to have significantly less handgrip strength and significantly lower high jump results than those observed in normotensive males, a difference that was not detected in women (Fig. 1).

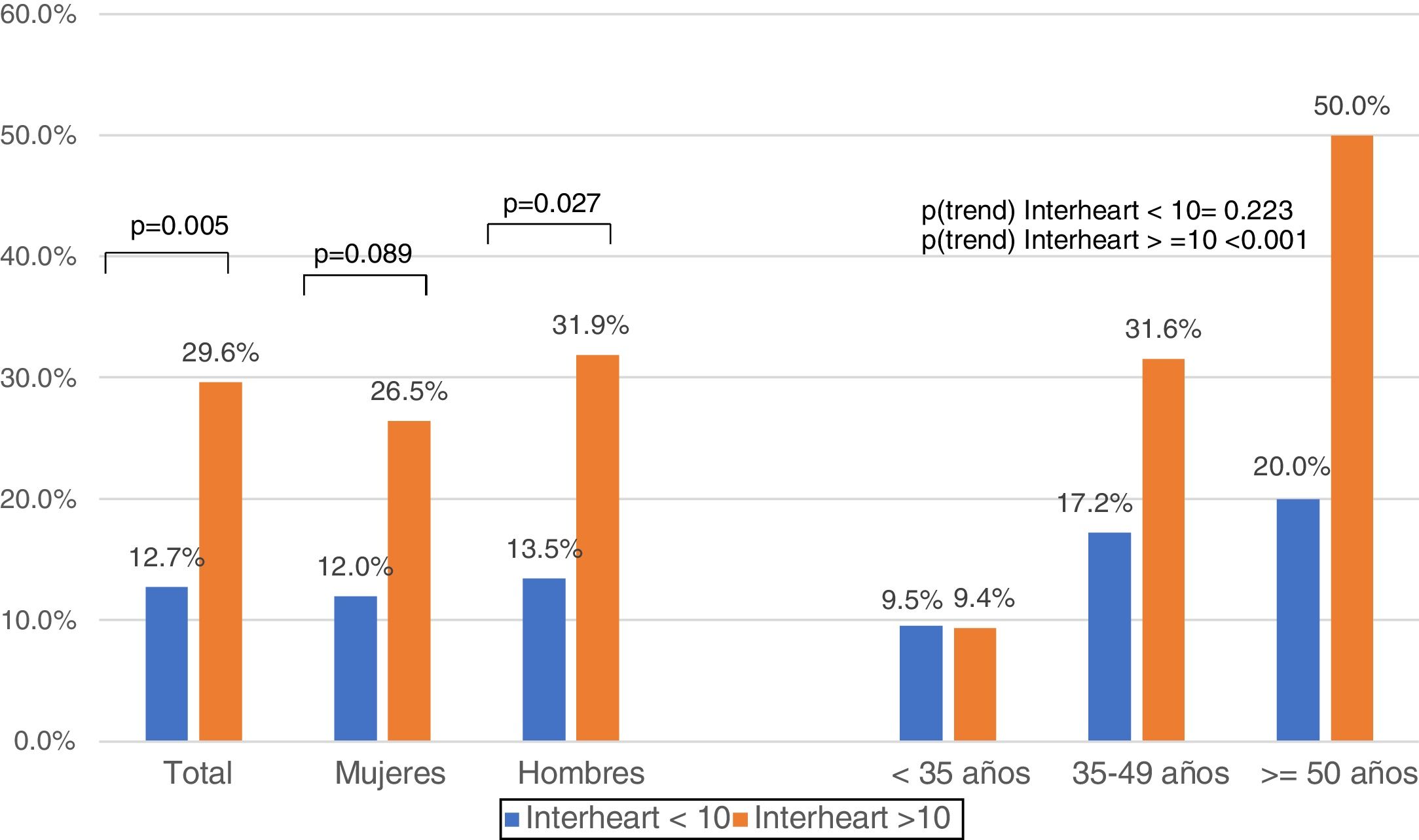

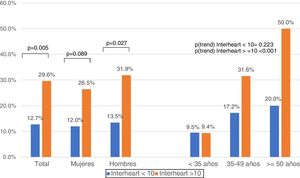

Eighty-one people (44.3% [95% CI 37–51.5%]) scored more than 10 on the INTERHEART questionnaire, which represents high cardiovascular risk. The presence of hypertension was significantly [p = 0.005] associated with increased cardiovascular risk in both sexes and increased with age (Fig. 2). The prevalence of DM2 was 6.59%. Forty-four participants (23.7%) were at risk for DM2, attaining scores that exceeded 12 on the FINDRISC scale.

DiscussionThe main finding of this study was that most of the participants, young medical specialists attending a Latin American medical conference, in which the importance of a healthy lifestyle and the identification and control of cardiovascular risk factors were discussed, displayed prevalence rates of risk factors for CVD and DM2 similar to those reported for the general population in Latin America.28−31 The fact that these healthcare workers have access to information, education, and communication regarding the importance of preventing and controlling these risk factors led to the assumption that they might be less prevalent [in this sample]. However, our results reveal that this assumption is untrue; despite the knowledge these participants have, their level of risk is very comparable to that of the rest of the population, a situation that has already been reported in other studies of health workers in our region.11–14 Thus, the prevalence of hypertension, sedentary lifestyle, overweight/obesity, dyslipidaemia, and smoking resembles that reported for the general population, resulting in high cardiovascular and DM2 risk scores, which is also commensurate with those reported for the non-medical population.28–31 These results are concerning, because, at least in principle, these are the professionals who should be orienting and advising patients on the importance of identifying, preventing, and controlling cardiovascular risk factors, by implementing healthy lifestyle habits, and if necessary, adequate adherence to medications proven to be useful in controlling them. Another area of interest is the high prevalence of overweight and abdominal obesity among the participants, especially among those with hypertension, most of whom also reported being sedentary. Likewise, hypertensive physicians had lower muscle strength values, both in the upper and lower body, which supports the recent proposal that an alteration in the relationship between adiposity and muscle mass/strength is a factor that correlated with increased risk of hypertension,33,34 total mortality, cardiovascular-related mortality, and cardiovascular events.35–37 The high prevalence of atherogenic dyslipidaemia detected in this group of Latin American physicians is especially noteworthy and has been reported in the general population.30,32,38

The concomitant presence of HTN, smoking, sedentary lifestyle, being overweight, and less muscle strength in a high percentage of these young physicians is possibly associated with the similar prevalence rates of DM2 as seen in the general population (more than 6.5%) and with the high risk score for developing DM2 in more than one in four participants.39,40

The nine recommendations of the World Health Assembly that are being implemented by the WHO, all of which target achieving the goals of reducing premature cardiovascular mortality by 25% by 2025, include: reducing smoking; improving awareness, treatment, and control of HTN; reducing excessive salt consumption, and increasing physical activity.41 For the most part, these actions entail a significant awareness on the part of the health team to put these recommendations into place through effective counselling. Our results suggest that, as a matter of priority, programmes must be carried out among physicians in Latin America to improve their appreciation of the importance of improving their own lifestyle habits, before assuming the role of healthy lifestyle counsellors that is fundamental to achieve the cardiovascular mortality reduction targets that all the governments in the region have committed to.

One of the main limitations of our study is its sample size and the findings should be interpreted in this context; nevertheless, the behaviour of the sample and our findings are in line with the literature. The present study reveals the importance of involving this specific population (healthcare professionals) as participants when studying cardiovascular disease. Another limitation of the study could be the absence of a dietary profile of the health professionals, but this was not an objective of the study. Finally, this work minimised potential measurement biases by using international techniques and standards for screening anthropometric and biological markers of cardiovascular disease.

ConclusionThe prevalence of CVD risk factors among the Latin American physicians studied was similar to that reported for the general population. The prevalence of high-risk scores for CVD and DM2 was high and presence healthy lifestyle habits was low. Adherence to healthy lifestyles must be improved among these physicians who are in charge of CVD risk factor management in the general population.

FundingThis work has been funded by Merck Laboratory.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

To the Faculty of Nursing of the University of Cartagena, whose students and professors contributed with the personnel who conducted the clinical, physical, and laboratory measurements.

Please cite this article as: Gaibor-Santos I, Garay J, Esmeral-Ordoñez DA, Rueda-García D, Cohen DD, Camacho PA, et al. Evaluación del perfil cardiometabólico en profesionales de salud de Latinoamérica. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33:175–183.