Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is the most common genetic disorder associated with premature coronary artery disease due to the presence of LDL-C cholesterol increased from birth. It is underdiagnosed and undertreated. The primary objective of the ARIAN project was to determine the number of patients diagnosed with FH after implementing a new screening procedure from the laboratory.

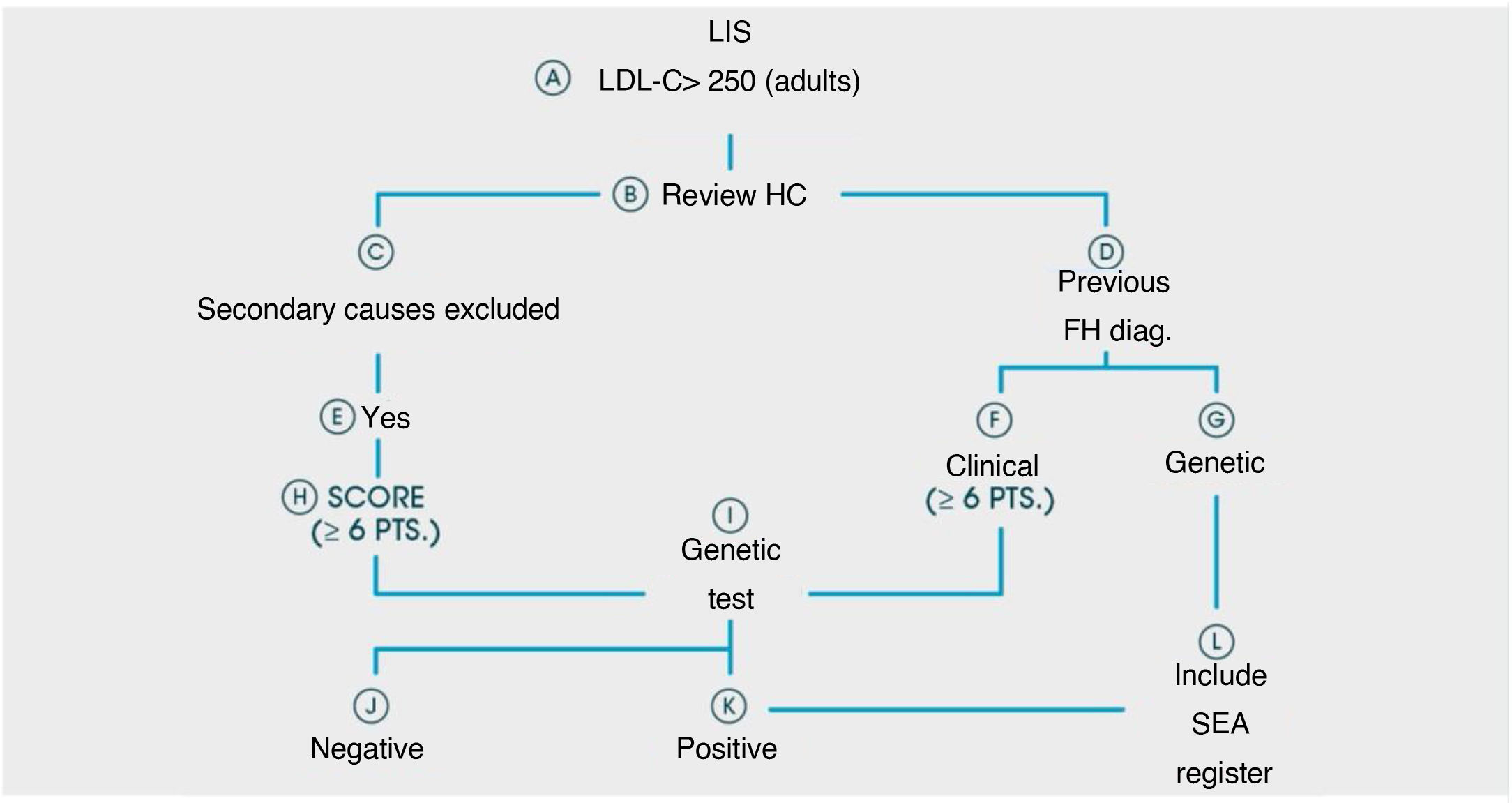

Material and methodsThis project was designed as a retrospective analysis by consulting the computer system. We selected from databases serum samples from patients ≥18 years with direct or calculated LDL-C >250 mg/dL from 1 January 2017 to 31 December 2018. Once secondary causes had been ruled out, the requesting primary care physician was notified that their patient might have FH and to arrange a priority appointment in the lipid unit. All patients with a score of ≥6 points according to the Dutch Lipid Clinic Criteria were proposed for a genetic study.

ResultsBy December 30th, 2020, 24 centres out of the initial 55 had submitted results. The number of patients analysed up to that point was 3,266,341, which represents 34% of the population served in those health areas (9,727,434).

ConclusionsThe identification of new subjects with FH through this new strategy from the laboratory and their referral to lipid units should increase the number of patients treated in lipid units and initiate familial cascade screening.

La Hipercolesterolemia Familiar (HF) es el trastorno genético más frecuente asociado con enfermedad coronaria prematura debido a la presencia de colesterol LDL incrementado desde el nacimiento. Se encuentra infradiagnosticada e infratratada. El objetivo primario del proyecto ARIAN es determinar el número de pacientes diagnosticados de HF tras implantar un nuevo procedimiento de cribado desde el laboratorio.

Material y métodosEste proyecto se ha diseñado como un análisis retrospectivo mediante consulta al sistema informático (SIL). Se seleccionaron de las bases de datos de laboratorio aquellas muestras de suero de pacientes ≥18 años con cLDL directos o calculados >250 mg/dl, desde el 1 de enero de 2017 hasta el 31 de diciembre de 2018. Una vez descartadas causas secundarias, se comunicó al médico de atención primaria solicitante la sospecha de que su paciente pudiera portar una HF y gestionar una cita prioritaria en la unidad de lípidos. Todos aquellos pacientes con una puntuación de ≥6 puntos de los criterios de las Clínicas Holandesas se les propuso un estudio genético.

ResultadosEl protocolo se presentó a 55 Laboratorios de forma individualizada. Hasta el día 30 de diciembre de 2020, el número centros que han remitido resultados es de 24. El número de muestras analizadas hasta ese momento fue de 3,266.341, lo que representa un 34% de la población atendida en esas áreas de salud (9,727.434).

ConclusionesLa identificación de nuevos sujetos con HF mediante esta nueva estrategia desde el laboratorio y su remisión a las Unidades de lípidos debe incrementar el número de pacientes tratados en las unidades de lípidos y permitir iniciar cribados en cascada familiar.

Familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) is the most common genetic disorder associated with premature coronary artery disease due to the presence of LDL-C cholesterol increased from birth. Its transmission mechanism is autosomal dominant and approximately half of the descendants of those affected will inherit the disease.1

Mutations in the LDL receptor gene (LDLR), or less frequently mutations of the apolipoprotein B gene (APOB) and of the Proprotein Convertase Subtilisin/kexintype9 (PCSK9) gene are the ones most responsible for this disease, although other genetic alterations also have an impact.2,3

Clinical diagnosis of FH is based on the presence of raised LDL-C concentrations, a family history of hypercholesterolaemia, a background of personal and familial cardiovascular disease and the presence of corneal xanthomas or arcus in the affected individual. Precision diagnosis is made through determination of the genetic mutation responsible for the hypercholesterolaemia.4,5

The prevalence of heterozygote FH in the general European population is approximately 1 out of every 300–500 people (1 out of every 250–300 in Spain), with an estimation of 100,000 being the number of Spanish people who present with this disorder. Data on the Catalan population considered there to be a prevalence of heterozygote FH of 1 case in every 192 inhabitants.6 Homozygote FH is much rarer. In the Spanish nation as a whole it is estimated that one out of every 495,000 inhabitants have this genetic form.7,8 Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches also differ greatly, depending on the different autonomous communities.9

In the Spanish Healthcare System as a whole and with current identification and care procedures, FH is a commonly undertreated disease and those who present with it often do not achieve the therapeutic objectives established by clinical practice guidelines: under 5% of cases with genetic confirmation of FH fall within the optimum therapeutic objective and under 15% of these are receiving the maximum combined treatment,10 although more recently combined treatment with PCSK9 (iPCSK9) inhibitors have contributed to improving these levels.11

This initiative aims at reversing this situation and proposes the implication of clinical laboratories in an FH screening strategy for the population.

A high percentage of patients with FH are not identified. If the analyst from the clinical analysis/clinical biochemical laboratory (CAL/CBL) alerted the requesting clinician and professionals at the lipid units (LU) of the LDL-C values being much higher than normal ranges, the percentage of those identified as affected by this disease would rise, as would the opportunity for them to achieve the lipid objectives established by clinical practice guidelines.

The primary aim of the ARIAN Project was to determine the number of patients diagnosed with FH after the implantation of a new screening procedure from the CAL/CBL. This paper describes the design of this project.

Material and methodsThis project was designed as a retrospective analysis by consulting the laboratory information system available in every clinical laboratory (LIS).

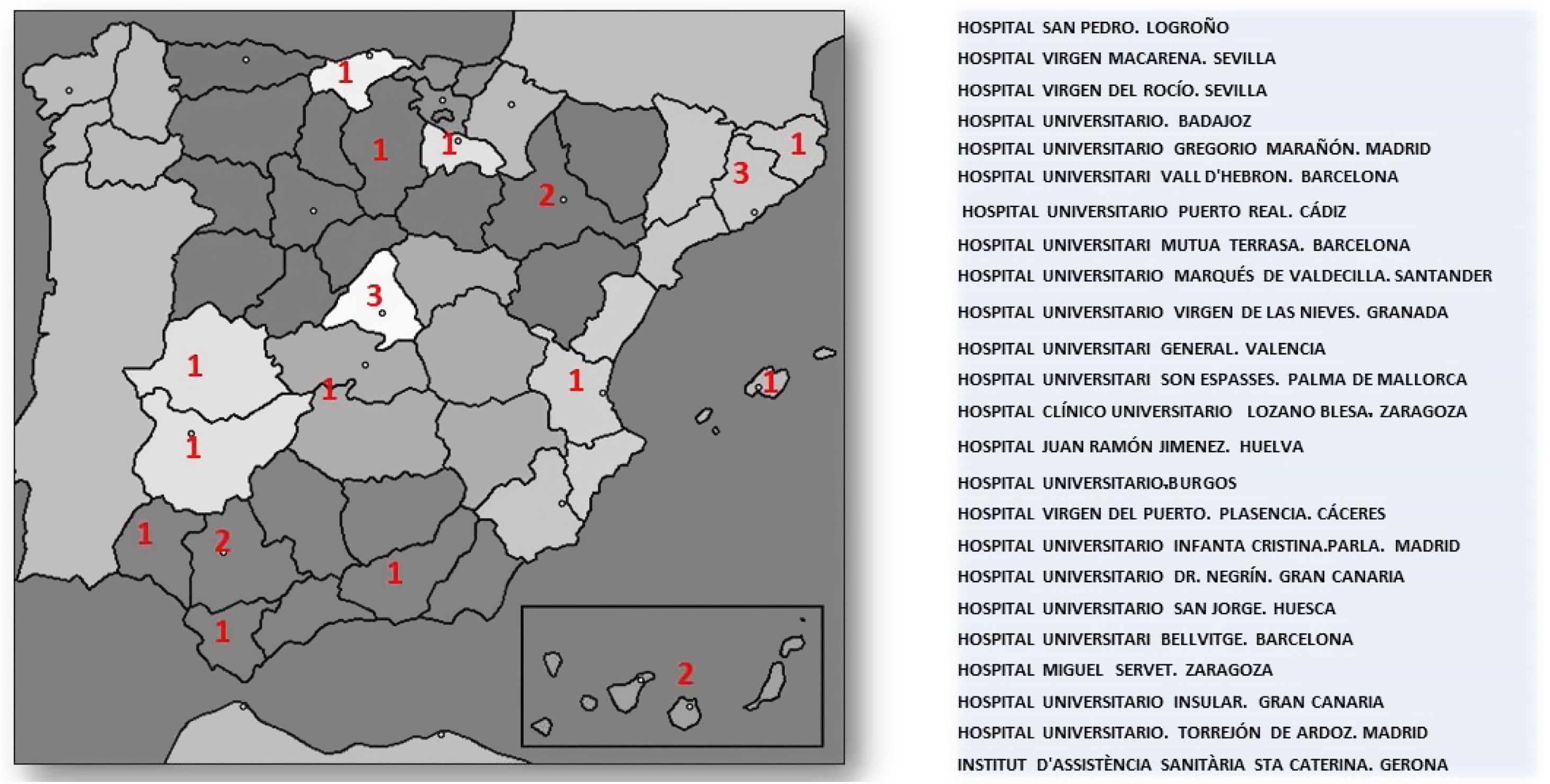

For the initial protocol a scientific committee was established comprising the coordinator of the Hospital Virgen de la Macarena (Dr. Teresa Arrobas) and 2 coordinators from the SEA (Dr. Angel Brea and Dr. Pedro Valdivielso). The protocol was presented in individualised format in 55 hospital centres. Following consensual modifications arrived at by all participating researchers at this meeting, the protocol was approved by the SEA scientific committee and by the ethics committee of the Hospital Virgen de la Macarena in Seville. Each participating centre obtained the approval from their local ethics and research committee.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria: samples from patients ≥18 years were selected from each LIS when they presented with direct or calculated LDL-C levels >250 mg/dl, from 1st January 2017 until 31st December 2018 (24 months). The LIS consultation included the patient’s first and family names; health area or hospital (important in the case of laboratories where primary care analytics were centralised); identification number or medical history; age, and, if the analytics contained them, the following non-mandatory biochemical parameters of the patient: glucose, HbA1c, TSH, triglycerides, GOT, GPT, GGT.

The selected cut-off point for LDL-C >250 mg/dl was regarded as appropriate as a level which would discriminate patients with possible severe hypercholesterolaemias, since according to the MED PED criteria for FH diagnosis, a patient with an LDL-C = 250−329 mg/dl would already have a minimum of 5 points. Also, this level obtained high sensitivity and specificity in the Civeira et al., study, where genetic diagnosis was compared with clinical diagnosis in the FH.12 Furthermore, LDL-C >250 mg/dl is a level which is over double the therapeutic objective for low risk patients in primary prevention according to the latest recommendations of the European Cardiology Society.13

Once consultation had been made, the analyst of each CAL/CBL ruled out—by consulting the parameters complementary to the tests resulting from the search—those patients who may have presented raised LDL-C levels secondary to other conditions (TSH alterations, liver diseases, pregnant women, etc.). Once the presence of a primary hypercholesterolaemia, suspected due to their FH levels, was verified, the primary care physician requesting the analysis was informed by the corporate email or by phone—that their patient was suspected of having FH and the details of the ARIAN project were given to them, suggesting they inform the patient of this and of the need for their referral to the corresponding LU so that they could be reviewed by the hospital specialist and could participate in the project. Simultaneously, the analyst of each CAL/CBL used the corporate email to send the list of patients detected who could potentially be included in the ARIAN Project to the corresponding LU clinician.

Patient’s referral to the LU: the LU appointment process was assessed in each hospital centre, attending the request for consultation by the primary care physician once they had been informed by the CAL/CBL. Priority of appointment was given to those with the highest LDL-C levels. If after a reasonable period of time—a fortnight—the LU had not received a request for consultation by the primary care physician, the LU was responsible for getting directly in touch with the physician in question, explaining the patient’s case and making a priority appointment with them. The primary care physician informed the patient and told them the time and place of their new appointment. The hospital was never directly in touch with the patient.

Once the patient went to the LU, a conventional consultation was made to assess the risk factors, family and personal background and they were informed about the ARIAN project. All the patients referred to the LU, regardless of their participation or non-participation in the ARIAN Project, received the care, advice and treatment regularly offered for the management of hypercholesterolaemias. A genetic study was suggested to all patients with a score of 6 or more points on the Dutch clinical criteria.14 The in vitro diagnostic platform used (GenIncode) made a complete analysis of the promoters of coding regions and exon-intron boundaries of 5 HF-associated genes (LDLR, APOB, PCSK9, APOE and STAP1) and 2 genes associated with other conditions which have a partial clinical overlap with FH features (recessive autosomal hypercholesterolaemia [LDLRAP1] and lysosomal acid lipase deficiency [LIPA]).15

The following variants associated with susceptibility to high levels of the following were also analysed: to Lp(a) (rs10455872 and rs3798220), response to statins (rs17244841, rs4149056 y rs2032582). In the case of polygenic hypercholesterolaemia the variants included in the LDLc Score (rs7412, rs429358, rs1367117, rs4299376, rs629301, rs1564348, rs1800562, rs3757354, rs11220462, rs8017377, rs6511720 y rs2479409)16 and variants included in the Cardio inCode Score (rs10455872, rs10507391, rs12526453, rs1333049, rs17222842, rs17465637, rs501120, rs6725887, rs9315051, rs9818870 and rs9982601) were analysed.17

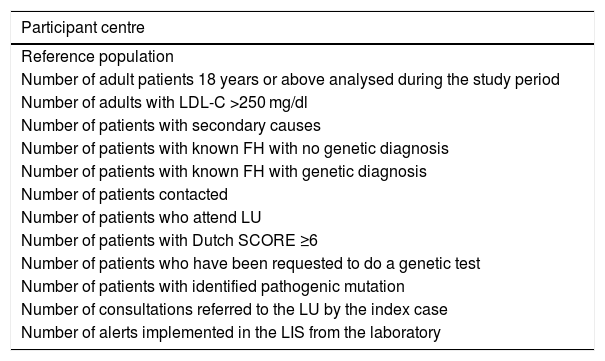

Each centre reported the information referred to in Table 1, in Excel format (Microsoft, Office 2016) to the electronic mail of the ARIAN project (proyecto.arian@se-arteriosclerosis.org) for their joint tabulation with data provided by the other participants (Table 1).

Specific data to be provided by the lipid units.

| Participant centre |

|---|

| Reference population |

| Number of adult patients 18 years or above analysed during the study period |

| Number of adults with LDL-C >250 mg/dl |

| Number of patients with secondary causes |

| Number of patients with known FH with no genetic diagnosis |

| Number of patients with known FH with genetic diagnosis |

| Number of patients contacted |

| Number of patients who attend LU |

| Number of patients with Dutch SCORE ≥6 |

| Number of patients who have been requested to do a genetic test |

| Number of patients with identified pathogenic mutation |

| Number of consultations referred to the LU by the index case |

| Number of alerts implemented in the LIS from the laboratory |

A patient flow diagram is shown in Fig. 1.

We calculated that each participating laboratory would collect data from 150,000 patients, and with 23 centres participating a population of 3,450,000 patients were estimated. A review of the data from the laboratories of the Hospital Virgen Macarena in Seville and from the Hospital Virgen de la Victoria in Malaga (unpublished data) indicated that .15% of the laboratory samples have a LDL-C >250 mg/dl, which in absolute numbers represents 5175 potential patients. From previous studies18 we would assume that 10% would be from secondary causes and that only 35% of the remainder would respond to the call to go to the LU and complete the clinical and genetic tests, if applicable. In keeping with the literature, based on a similar study,19 we considered that 10% of patients who would go to the LU would have a score >5 in the criteria of the Dutch lipid clinic network. As a result of all of this, the number of potential patients to be treated by means of a genetic test would be approximately 163.

Ethical aspectsThe project was approved by the Ethics Committee from the reference hospital (Hospital Virgen de la Macarena, Seville) dated 16th February 2019. All the patients included in the ARIAN project were given an informative leaflet on the project, together with an informed consent form. All the patients signed the informed consent form.

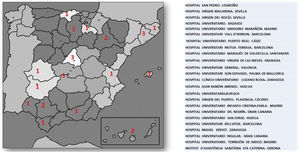

ResultsUp until 30th December 2020, the number of laboratories and LU which had sent results was 24 out of the initial 55 that signed up for the project. The number of samples analysed by the participating laboratories until that time was 3,266,341, which represents 34% of the population covered by these health areas (9,727,434). The geographical distribution and participating centres are shown in Fig. 2.

DiscussionSeveral strategies have been used for early diagnosis, which may be summarised into 3 types of screening: population, opportunist and familiar.20 The opportunist strategy—that which takes place when the patient interacts with the health system and in our specific case with the laboratory—is of enormous value.

Several studies have published their findings on the performance of the opportunist strategy in identifying patients with FH.18,19,21 The intervention of the laboratory in the screening of FH has been shown to be highly useful. One study showed that a simple call from the clinical analyst to the primary care physician suggesting that the patient be referred to a specialist unit was more successful (27% of referral cases) compared to the traditional model (4%).21 During a period of one year, with a similar design to ours, one Australian group published, over a total of 99,467 saline samples which included LDL-C, an FH prevalence defined by LDL-C >250 mg/dl of 1 out of every 398 samples.18 Another Australian study also showed that the search for FH cases defined by DLCN >5 through the clinical laboratory was higher and more efficient than the database usage from primary care or occupational check-up consultations.19

The data provided by the ARIAN project led to an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with FH after establishing a screening procedure with the clinical laboratory, so that the performance of this strategy may be assessed using the estimation of the percentage of patients studied with accurate FH diagnoses compared with the total sample. A collateral, but equally important issue was that of creating laboratory alerts which consisted of including recommendations to the clinicians within reports of the biochemical determinations so that they referred their patients to the LU when the LDL-C concentrations were above certain levels.22 Thus, the SEA published their referral criteria for patients to LU.23 Although this is relevant, a recent surgery showed that only 17% of 286 laboratories in Europe include an alert in suspected cases of FH in their reports.24

The identification of new subjects with FH and their referral to LU should lead to an improvement in their treatment and in the opportunity to receive hospital dispensing drugs, such as iPCSK9 inhibitors. The introduction of these drugs has helped to improve control of hypercholesterolaemia, although access to them is not generalised and prescription remains restricted to certain minimum LFL-C levels, and the coexistence of an established vascular disease.25 Treatment with iPCSK9 inhibitors not only also reduces LDL-C levels when added to combined conventional therapy (statins + ezetimibe),11 but is also capable, within a short space of time, of restoring cutaneous cholesterol deposits.26 SEA is in favour of a rational use of iPCSK9 inhibitors in FH, taking into account the vascular risk of each patient and not just the LDL-C level achieved with conventional therapy.27

Once the ARIAN project has been terminated, the percentage of patients diagnosed with FH through this laboratory screening strategy who achieve lipid therapeutic objectives established by the “European guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias” will be verified.13 These data will be compared with those already existing in the SEA dyslipidaemia register.28

FinancingThe ARIAN Project received a 2017 FEA/SEA grant and additional funding from Sanofi. The sponsor collaborated in the project design and in the collection of samples. The sponsor did not intervene in data interpretation, redaction of the article or in the decision to send the article for publication.

Conflict of interestsDr. Pedro Valdivielso Felices declares that he has received the following funds from MSD, Amgen, Sanofi, Amarin, Akcea, Mylan, Ferrer, Novartis, Amryt for conferences, not related to the completion of this study. Dr. Angel Brea Hernando declares he has received external funding relating to the completion of this study in the form of a grant from the Spanish Atherosclerosis Society and Sanofi. Dr. Teresa Arrobas Velilla has received external funding relating to the completion of this study in the form of a grant from the Spanish Atherosclerosis Society and Sanofi, and has received the following funds from Amgen and Sanofi for conferences, not related to the completion of this study.

The authors wish to express their thanks to the patients for their collaboration.

Hospital Virgen Macarena (Seville): Begoña Gallardo Alguacil, Ramon Pérez Temprano, Mar Martínez Quesada, Miguel Ángel Rico. Hospital Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla): Lourdes Diez Herrán and Ovidio Muñiz Grijalbo. Hospital Universitario de Badajoz: Purificación García Yun, Francisca Jiménez-Mena Villar and Francisco Morales Pérez. Hospital Gregorio Marañón (Madrid): Olga González Albarrán, Mercedes Herranz Puebla, Carolina Puertas Robles. Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron: Silvia Campos Anguila and Joan Lima Ruiz. Hospital Universitario Marqués de Valdecilla. (Santander): Armando Raúl Guerra Ruiz and José Luis Hernández Hernández. Hospital Universitario Virgen de las Nieves and Hospital Universitario clínico San Celicio (Granada): José Vicente García Lario, Pablo González Busto, Fernando Rodríguez Alemán, María Mar Águila García, Fernando Jaén Ávila. Hospital General de Valencia: Goitzane Marcaida Benito and Juan José Tamarit Gracia. Hospital Universitario Son Espasses (Palma de Mallorca): Cristina Gómez Cobos and Juan Ramón Urgeles Planella. Hospital Clínico Universitario Lozano Blesa (Zaragoza): Luis Irigoyen Cucalón, José Antonio Gimeno Orna, José Ruiz Budría. Hospital Juan Ramón Jiménez (Huelva): Ignacio Vázquez Rico and Jessica Roa Garrido. Hospital Universitario de Burgos: Enrique Ruiz Pérez, María Maravi Álvarez, Laura de la Maza Pereg, María Victoria Poncela García, María Martin Palencia. Hospital Virgen del Puerto (Plasencia): David Peñalver Talavera, Montaña Jiménez Álvaro. Hospital Universitario Infanta Cristina de Parla (Madrid): Marco Puma Duque, Almudena Vigil Rodríguez, Juan Manuel Fernández Alonso. Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín: José Alfredo Martin Armas, Magdalena León Mazorra, Casimira Domínguez Cabrera, Lidia Esther Ruiz Gracia. Hospital Universitario San Jorge (Huesca): José Puzo Foncillas. Hospital Universitario de Bellvitge: Xavier Pintó Sala and María José Castro Castro. Hospital Miguel Servet (Zaragoza): Fernando Civeira Murillo and Pilar Calmarza. Hospital Insular de Gran Canaria: Rosa Sánchez Hernández and Marta Riaño Ruiz. Hospital Universitario de Torrejón: Camino García García-Lescun, María Almudena Amor, Eduardo Alegría. Institut d'Assistencia Sanitaria Santa Caterina (Gerona): Cristina Soler Ferrer and Mercé Montesino Costa. Hospital San Pedro (Logroño): Antonio Rus and Marta Casañas.

The names of the ARIAN Project researchers are listed in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Arrobas Velilla T, Brea Á, Valdivielso P, los investigadores del Proyecto ARIAN. Implantación de un programa de cribado bioquímico y genético de hipercolesterolemia familiar. Colaboración entre el laboratorio clínico y las unidades de lípidos: diseño del Proyecto ARIAN. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33:282–288.