This document has discussed clinical approaches to managing cardiovascular risk in clinical practice, with special focus on residual cardiovascular risk associated with lipid abnormalities, especially atherogenic dyslipidaemia (AD).

A simplified definition of AD was proposed to enhance understanding of this condition, its prevalence and its impact on cardiovascular risk. AD can be defined by high fasting triglyceride levels (≥2.3mmol/l/≥200mg/dl) and low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-c) levels (≤1.0/40 and ≤1.3mmol/l/50mg/dl in men and women, respectively) in statin-treated patients at high cardiovascular risk. The use of a single marker for the diagnosis and treatment of AD, such as non-HDL-c, was advocated. Interventions including lifestyle optimisation and low density lipoprotein (LDL) lowering therapy with statins (±ezetimibe) are recommended by experts. Treatment of residual AD can be performed with the addition of fenofibrate, since it can improve the complete lipoprotein profile and reduce the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with AD. Others clinical condictions in which fenofibrate may be prescribed include patients with very high TGs (≥5.6mmol/l/500mg/dl), patients who are intolerant or resistant to statins, and patients with AD and at high cardiovascular risk. The fenofibrate-statin combination was considered by the experts to benefit from a favourable benefit-risk profile.

In conclusion, cardiovascular experts adopt a multifaceted approach to the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, with lifestyle optimisation, LDL-lowering therapy and treatment of AD with fenofibrate routinely used to help reduce a patient's overall cardiovascular risk.

El documento incluye los aspectos clínicos para abordar el riego cardiovascular en la práctica clínica, con especial atención en el riesgo cardiovascular residual asociado a anomalías lipídicas, especialmente dislipemia aterogénica (DA).

Se propone una definición simplificada de DA para mejorar la comprensión del problema, su prevalencia y su impacto en el riesgo cardiovascular. La DA puede ser definida por aumento de los niveles de triglicéridos (≥2,3mmol/l/≥200mg/dl) y descenso de cHDL (≤1,0/40 y ≤1,3mmol/l/50mg/dl en hombres y mujeres, respectivamente) en pacientes con alto riesgo cardiovascular en tratamiento con estatinas. Se recomienda el empleo de un marcador simple para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de la DA, tal como es el colesterol-no-HDL. Para los expertos, la intervención terapéutica incluye optimización del estilo de vida y fármacos hipocolesterolemiantes (estatinas ±ezetimiba). El tratamiento de la DA residual se puede completar con la adición de fenofibrato, al objeto de mejorar el perfíl lipídico completo y reducir el riesgo de accidentes cardiovasculares en los pacientes con DA. Otras situaciones clínicas en las que se puede prescribir fenofibrato incluyen los pacientes con hipertrigliceridemias elevadas (≥5,6mmol/l/500mg/dl), enfermos con intolerancia o resistencia a las estatinas, y pacientes con alto riesgo cardiovascular que presentan DA. Los expertos consideran que la combinación estatina-fenofibrato muestra un perfil favorable riesgo-beneficio.

En conclusión, los expertos proponen un manejo multifactorial para la prevención de la enfermedad cardiovascular aterosclerótica mediante optimización del estilo de vida, tratamiento para reducir el cLDL y tratamiento de la DA con adición de fenofibrato de forma rutinaria, al objeto de reducir el riesgo cardiovascular global del paciente.

Treatment with statins is critical to cardiovascular (CV) disease prevention due to their capacity to reduce low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels. A decrease in cardiovascular events has also recently been demonstrated when an additional LDL-C reduction is achieved, either through high doses of statins or the combination of a statin with another cholesterol-lowering drug such as ezetimibe, as shown by the IMPROVE-IT study.1 However, statins do not eliminate the residual risk deriving from other lipid abnormalities, such as hypertriglyceridaemia and/or low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), which can cause additional cardiovascular events.

A consensus document representing the opinion of European cardiovascular disease experts has recently been published. It describes the importance of atherogenic dyslipidaemia (AD) in contributing to sustained elevated CV risk, as well as the role of the statin-fenofibrate combination in offering a comprehensive approach to dyslipidaemia treatment in the face of AD, when the patient also requires supplementary cholesterol-lowering treatment due to elevated CV risk.2

The aim of this article is to summarise the opinion of these experts concerning the clinical decisions that govern CV risk management when specifically faced with this type of residual risk associated with atherogenic dyslipidaemia in clinical practice.

Atherogenic dyslipidaemia and residual cardiovascular riskNumerous factors contribute to CV risk, whether non-lipid related (age, gender, smoking, alcohol, diabetes mellitus, obesity, hypertension) or lipid-related (increased LDL-C, elevated triglyceride levels and or low HDL-C). Statins, in combination with an improved lifestyle, reduce the rate of CV events in many patients. Nevertheless, it is common for patients to still suffer cardiovascular events, particularly in the event of sustained lipid metabolism abnormalities. This CV risk is known as “residual risk”. In accordance with the Residual Risk Reduction Initiative (R3i),3 this can be defined as the sustained risk of cardiovascular events in individuals despite meeting LDL-C, blood pressure and blood glucose objectives, having taken conventional therapeutic measures.

The main obstacle to treating CV risk due to dyslipidaemia, particularly AD (characterised by high triglycerides and low HDL-C), is the lack of awareness of the issue and the impact that AD can have on CV risk. It is therefore important to raise awareness of the importance of residual CV risk associated with AD and the importance of treating the condition beyond reducing LDL-C levels. Furthermore, once clear treatment objectives have been recognised and established, doctors are in a better position to identify and treat patients with residual risk, whether in primary or secondary prevention.

R3i defines AD as the imbalance between proatherogenic triglyceride-rich apolipoprotein B-containing-lipoproteins and antiatherogenic apolipoprotein A-I-lipoproteins (as in high-density lipoprotein, HDL).3 A simplified definition is the combination of an excess of fasting triglycerides (≥2.3mmol/l/≥200mg/dl) and an HDL-C deficiency (≤1.0mmol/l/40mg/dl and ≤1.3mmol/l/50mg/dl) in men and women, respectively. Although LDL-C concentrations tend to be normal or only moderately increased, in AD, LDL particles are typically small and dense.

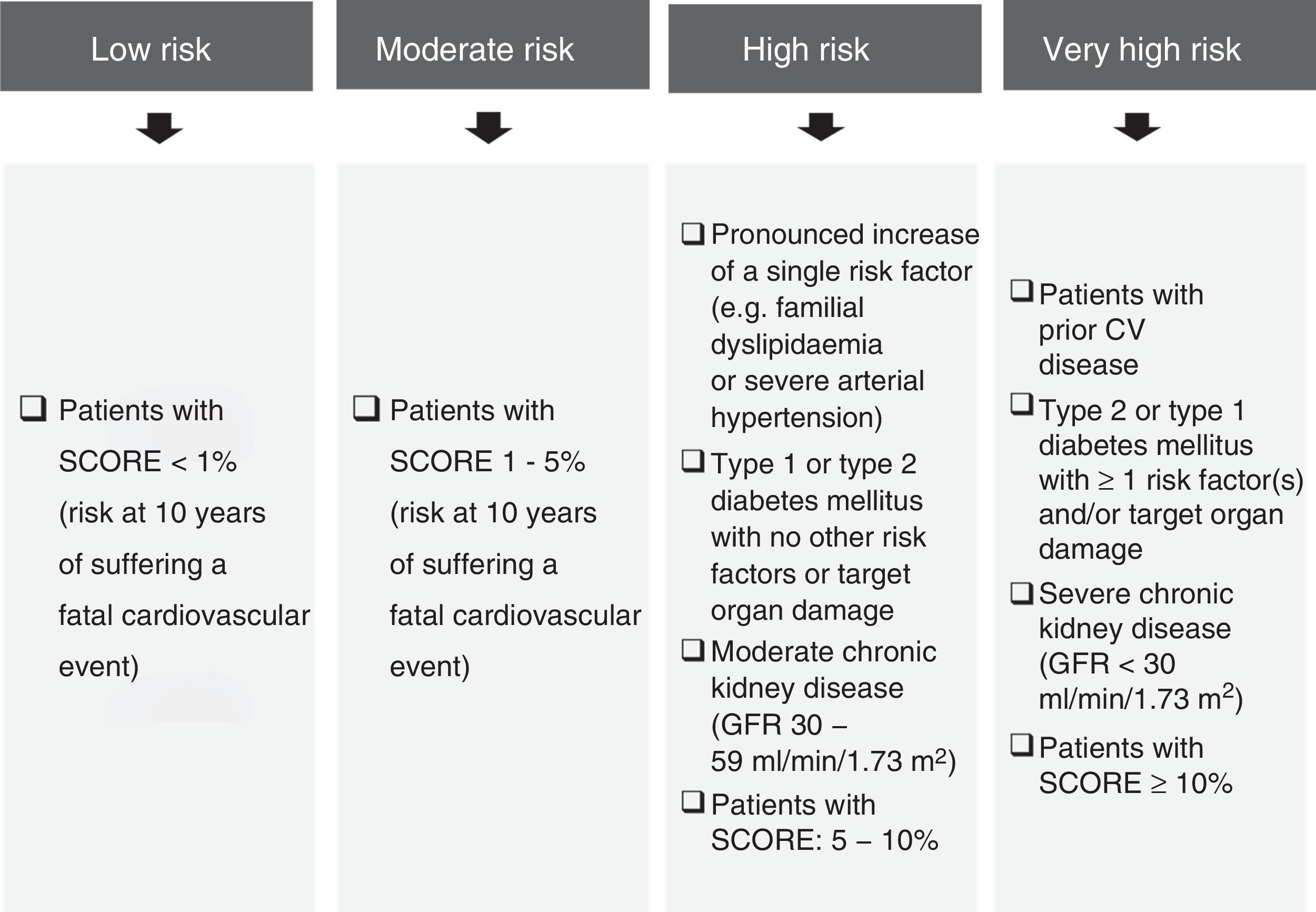

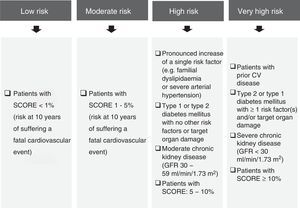

The prevalence of AD is high, particularly in high-risk subjects (European Atherosclerosis Society and European Society of Cardiology criteria) (Fig. 1),4 people with diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome,5,6 chronic kidney disease, familial combined hyperlipidaemia,7 overweight women8 or women with polycystic ovary syndrome.9

Cardiovascular risk classification criteria.4,23

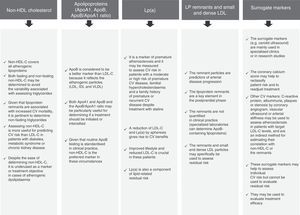

In practice, the lipid profile should include total cholesterol, LDL-C, fasting triglycerides and HDL-C. LDL-C and non-HDL cholesterol (non-HDL-C, calculated as total cholesterol minus HDL-C) are considered to be the most important parameters and should be applied as therapeutic objectives.

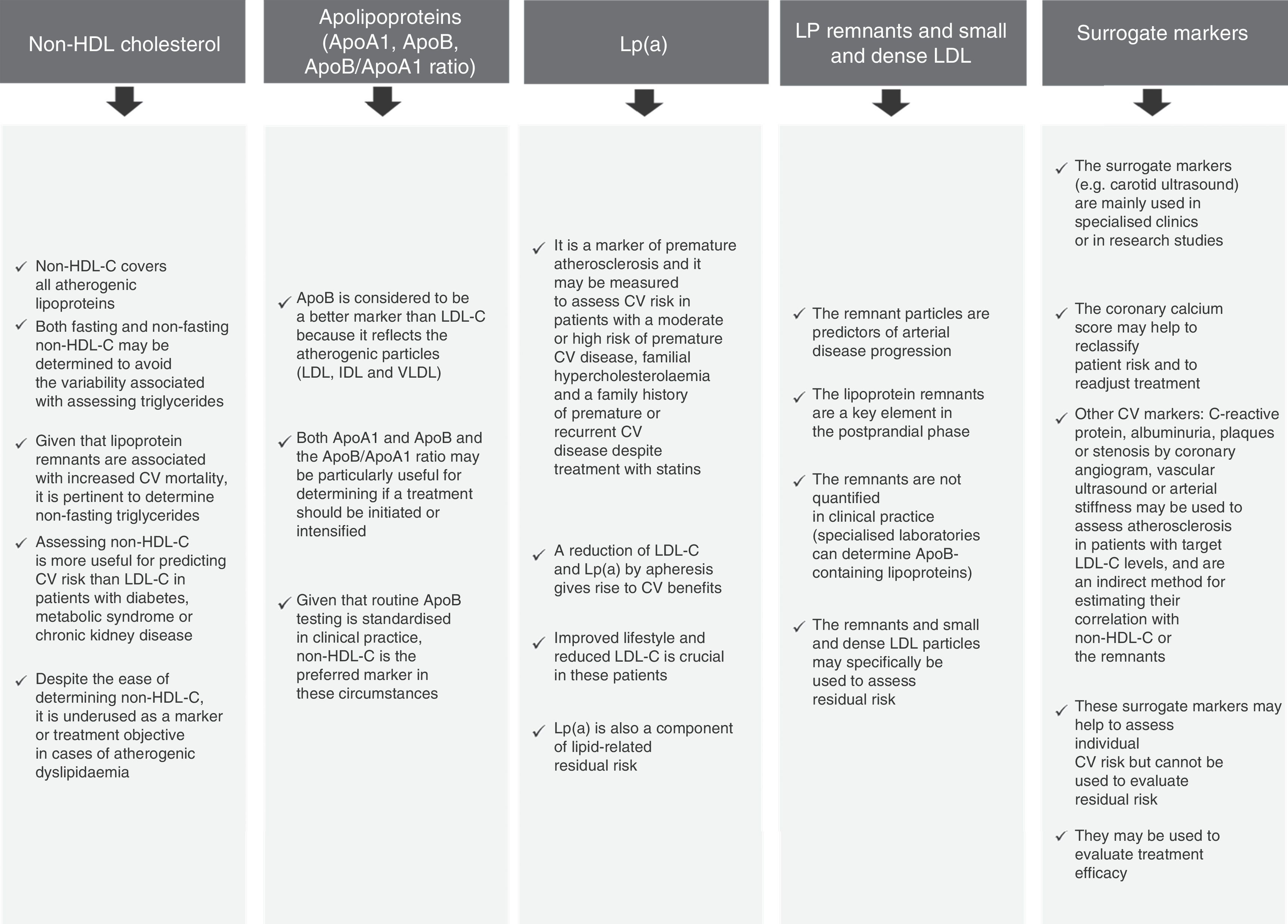

Other markers to assess lipid-related residual risk could also be considered (Fig. 2),10–15 even though non-HDL-C is particularly useful, easy to determine and widely acknowledged in the international guidelines. That is why it is recommended as a secondary treatment objective in the European Guidelines4 in patients with hypertriglyceridaemia and diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome or chronic kidney disease. It should be noted that the NICE guideline16 recommends non-HDL-C as a primary treatment objective in all patients, as it represents all atherogenic cholesterol.

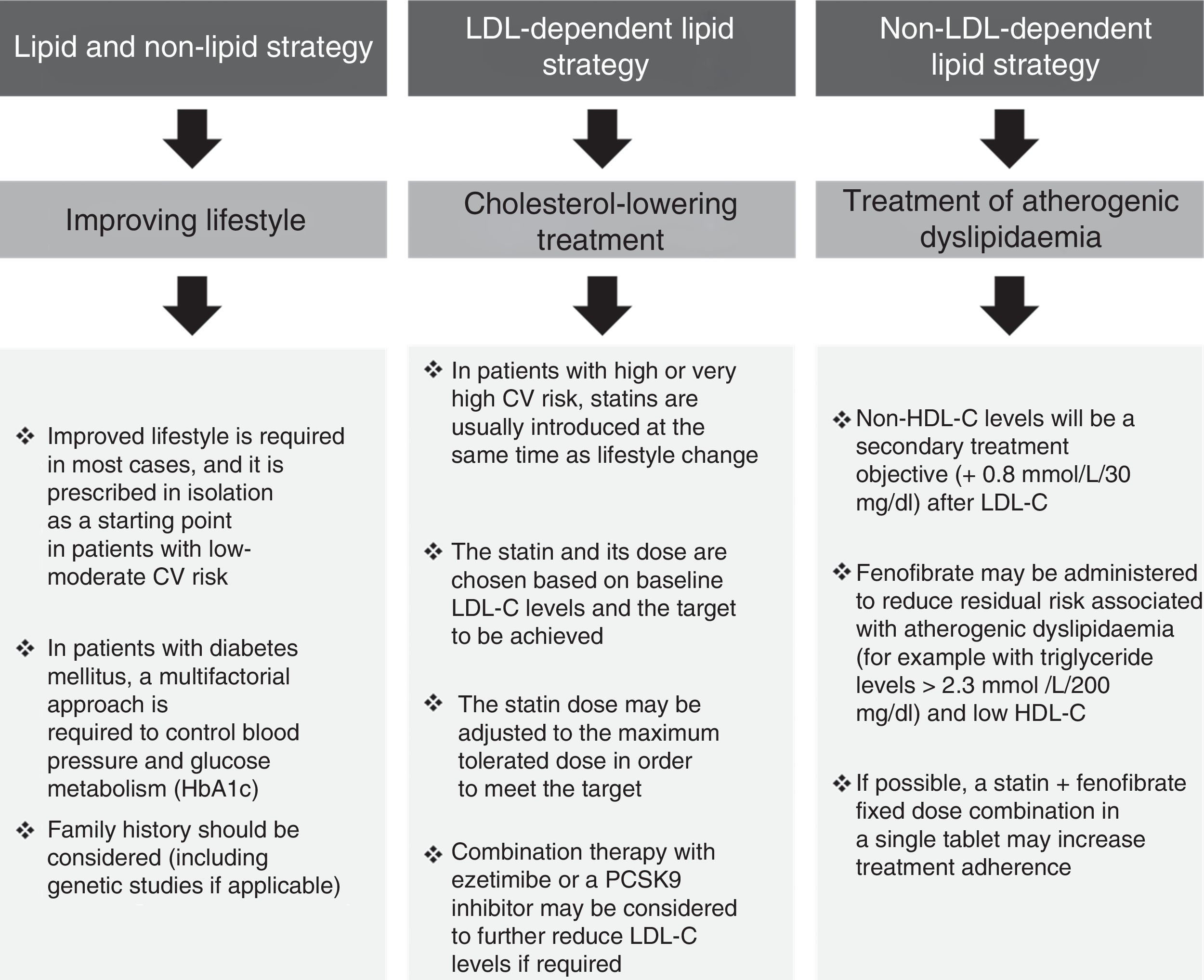

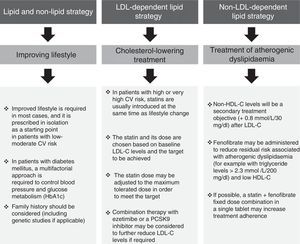

Overall cardiovascular riskThe multifaceted nature of arteriosclerotic CV disease and its risk factors drive the need for a multifactorial approach to its prevention and treatment (Fig. 3). This usually focuses on three aspects: (1) lifestyle; (2) reducing LDL-C; and (3) treating AD.

We follow the European recommendations4 that propose individualised treatment based on individual risk and on treatment objectives, whereas the American guidelines focus solely on reducing LDL-C.17

Improving lifestyleIt is essential to inform the patient of the benefits of improving their diet, increasing their level of physical activity, limiting alcohol consumption, quitting smoking and assessing their sleep patterns. The importance of these measures should not be underestimated. Lifestyle changes may improve AD in conjunction with 5–10% weight loss. The impact of lifestyle is greater still in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, including improved glycaemic control.

Cholesterol-lowering treatmentIn high-risk or very high-risk patients, lipid-lowering treatment is usually initiated with statins at the same time as lifestyle changes are introduced. The LDL-C targets set out in the European guidelines are established in accordance with individual CV risk: <2.5mmol/l/100mg/dl for high-risk patients and <1.8mmol/l/70mg/dl for very high-risk patients.4 It should also be noted that an additional decrease with combination therapy (statin plus ezetimibe) could lead to an even greater risk reduction.1 This benefit, in both absolute and relative terms, is greater in patients with diabetes mellitus18 and may drive the need to stipulate even sharper reductions in future clinical practice guidelines, i.e. more than 70mg/dl in very high-risk patients or patients in secondary prevention.19

Treatment of atherogenic dyslipidaemiaThe impact of AD on residual CV risk is of such magnitude that even patients treated with statins and with controlled LDL-C are 71% more likely to suffer severe CV events if they also have abnormal triglyceride and/or HDL-C levels.20 As such, treating AD itself in high-risk and very high-risk patients, including those with diabetes mellitus, could significantly reduce the incidence of cardiovascular events.

Although the most significant atherogenic lipoproteins are LDLs, other apoB containing lipoproteins (such as triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants) may lead to cholesterol being deposited in the arterial intima.21 Furthermore, lipoprotein size is a determining factor for atherogenesis because the remnant particles that carry triglycerides penetrate the arterial intima and are retained by the connective tissue matrix, contributing directly to atheroma plaque formation and progression.21 As such, these pathogenic aspects justify the importance of additional AD treatment, including in combination with statins, in order to reduce residual CV risk.22 A very sizeable proportion of high-risk patients do not meet the LDL-C targets, even when administered high-dose statins or a statin plus ezetimibe in combination, or they have additional AD. In order to reduce risk, an LDL-C reduction of at least 50% has been proposed in these patients,4,23 as well as additional treatment to address excess triglyceride levels and/or HDL-C deficiency, should these abnormalities manifest. In clinical practice, these abnormalities have been classically treated with niacin or fibrates. Fenofibrate has been found to be the drug with the most favourable pharmacological interaction for use in conjunction with statins, and as such it is the drug of choice for this combination.24 The administration of niacin with a statin has shown no additional benefit over statins in monotherapy and it is a less potent cholesterol-lowering drug than statins.25 Following the results of the latest clinical trials and due to its risk-benefit ratio and its side effects, niacin is not recommended for use in Europe. Finally, proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 inhibitors (PCSK9) have recently come onto the market. Although they offer a potent additional cholesterol-lowering effect and have been trialled on lipoprotein(a) [Lp(a)], no definitive studies on AD have been conducted to date.26

FenofibrateThe benefit of the statin-fenofibrate combination in patients with AD was corroborated by the ACCORD-Lipid study.20 This study found that risk of CV death, myocardial infarction or stroke fell by 31% in diabetic patients with AD who received this combination, compared to patients who received the statin in monotherapy. The number needed to treat (NNT) to achieve this benefit was 20 patients over five years.27 These data force us to consider the use of drugs other than statins, such as fenofibrate, to treat AD, as also shown by the FIELD study subanalyses,28 although definitive evidence of their morbidity and mortality would have to be confirmed in specifically designed studies.

Fenofibrate is recommended to reduce triglyceridaemia.4 To avoid fluctuations caused by variations in measuring triglycerides, applying non-HDL-C as a therapeutic objective may prove to be particularly beneficial (at a level of 0.8mmol/l/30mg/dl plus the target LDL-C level) when it comes to initiating treatment with fenofibrate in patients with AD.

Importance of combination therapyAs mentioned above, in light of the benefits obtained with the combination of statins plus ezetimibe1 or a PCSK9 inhibitor,29 or the combination of a statin plus fenofibrate in patients with AD,20 in order to improve the overall lipid profile, combination therapy should be considered in high-risk and very high-risk patients.

Adherence is key when it comes to treating risk factors, as shown in hypertension or with diabetes mellitus. Adherence to chronic treatment is far from optimal, and this is especially true of lipid-lowering drugs. Furthermore, adherence to risk factor treatments is crucial in patients in secondary prevention, and it has been shown that adherence is associated with a reduction in cardiovascular events.30

As such, reducing the number of tablets to take in fixed-dose combinations could be of particular interest, despite the lack of definitive clinical data concerning their impact on adherence and treatment compliance. The combination of a statin with fenofibrate could be of particular benefit to patients with diabetes mellitus or in secondary prevention as these patients are usually polymedicated.31

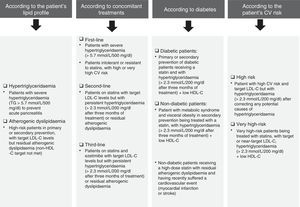

Use of fenofibrate in clinical practiceFenofibrate is usually administered in clinical practice to treat residual AD in patients receiving statins and to reduce the risk associated with AD in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients, despite the fact that the treatment of AD is not the primary objective.

Fenofibrate's approved indications are well defined. According to the European Medicines Agency (EMA), fenofibrate is indicated as a supplementary treatment to diet and lifestyle in the following circumstances:

- •

Severe hypertriglyceridaemia, with or without low HDL-C levels.

- •

Mixed hyperlipidaemia, when the statin is not tolerated or is contraindicated.32

- •

Mixed hyperlipidaemia in patients with high CV risk, together with a statin, when triglyceride and HDL-C levels are not properly controlled.33

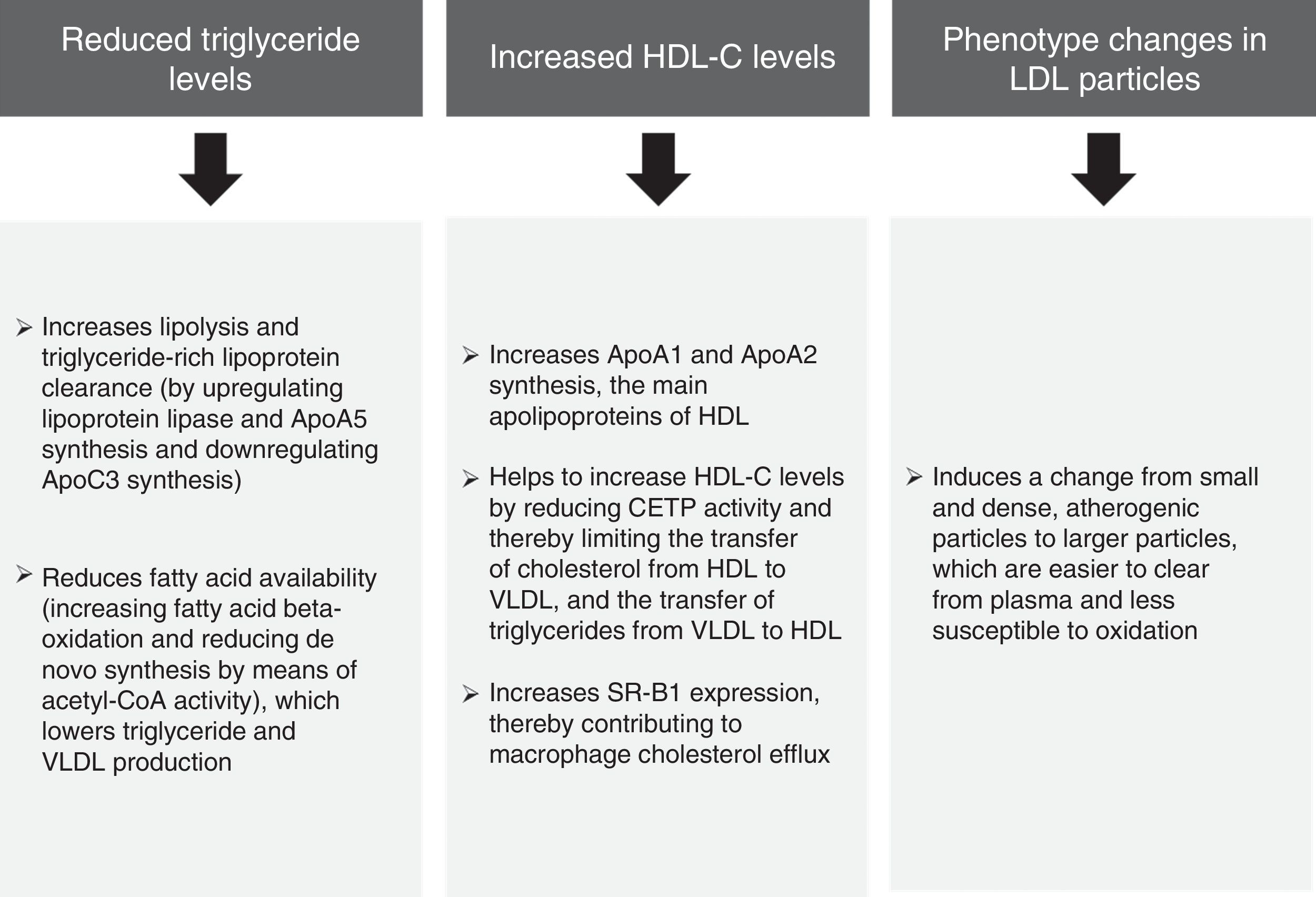

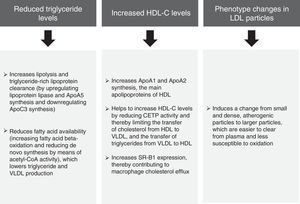

The pooled analysis of clinical trials in patients with mixed dyslipidaemia in which fenofibric acid (active metabolite of fenofibrate) in combination with the most potent statins (simvastatin, atorvastatin and rosuvastatin) confirmed that this combination significantly improves the overall lipoprotein profile in patients with AD.34 The subanalysis of patients with diabetes mellitus also demonstrated that this combination improves the lipid profile to a greater extent than statins administered in monotherapy.35 In light of the above, it can be unequivocally claimed that the lipid effects of fenofibrate (Fig. 4) may help to reduce the risk of macrovascular complications in patients with AD, and especially when AD manifests.

Lipid effects of fenofibrate.52,53

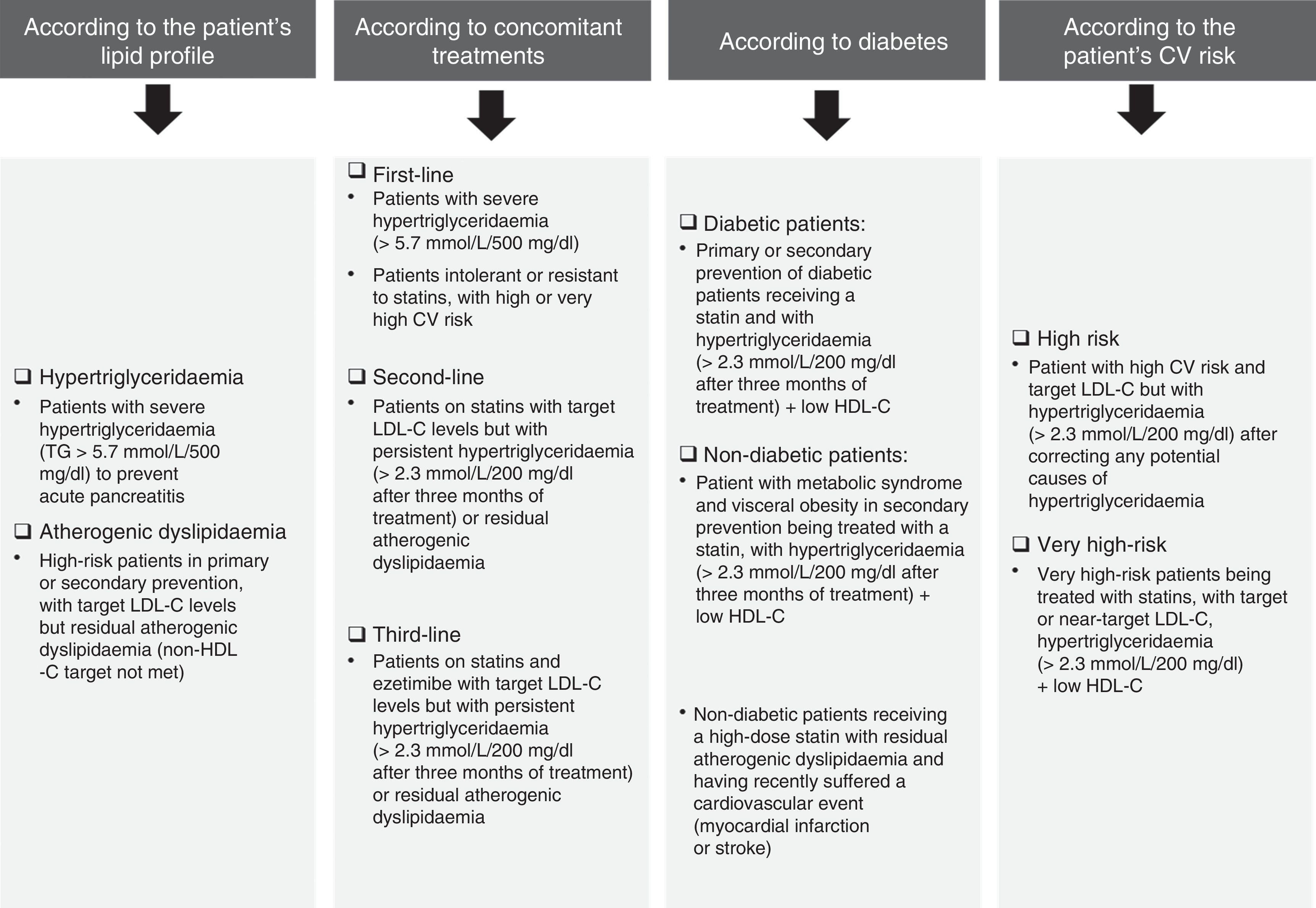

Fig. 5 details the situations associated with fenofibrate's clinical indications in accordance with the patient's lipid profile, the presence/absence of diabetes and any concomitant therapies. Notwithstanding the above, fenofibrate may also be considered in patients who do not meet the LDL-C targets despite intensive cholesterol-lowering treatment and who have high triglyceride levels and low HDL-C, as well as in high-risk and very high-risk patients, or in secondary prevention. Although the effect of fenofibrate on LDL-C is moderate, it effectively reduces small and dense LDL particles that are typical of AD.

When is fenofibrate administered in first-, second- and third-line treatment?Fenofibrate may be administered in monotherapy to patients with extremely elevated triglycerides (≥5.7mmol/l/500mg/dl) in order to reduce the risk of acute pancreatitis. It may also be prescribed as a first-line treatment to patients in primary or secondary prevention, or patients with a high or very high CV risk, resistant or intolerant to statins or who have moderately high triglyceride levels. It should be noted that a recent consensus panel statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society on statin-associated muscle symptoms recommends the addition of ezetimibe with or without a fibrate (not gemfibrozil) as a first-line treatment to achieve the LDL-C treatment objectives.36 Fenofibrate is administered as a second- or third-line treatment after lifestyle change and treatment with statins plus ezetimibe.

It may also be considered as a first-line treatment in patients with AD and insulin resistance (without increased LDL-C levels). Many patients with no prior CV history but with AD and metabolic syndrome, abdominal obesity or type 2 diabetes mellitus may be considered to be high-risk patients and candidates for treatment with a statin-fenofibrate combination.37

Can fenofibrate be administered to both diabetic and non-diabetic patients?As diabetes is associated with increased CV risk, patients with type 2 diabetes are considered both by the ESC/EAS European guidelines,4 and by the EASD guidelines on diabetes,38 to be high risk or very high risk. It is vital to control AD in these patients, which can be achieved with fenofibrate. However, whilst the administration of fenofibrate to diabetic patients is appropriate because they tend to have AD, it should be noted that administration of the drug is irrespective of diabetes, as it more specifically depends on whether or not the patient has AD. The ESC/EAS guidelines also recommend pharmacological treatment for patients with high CV risk and hypertriglyceridaemia >2.3mmol/l/200mg/dl, which cannot be controlled by lifestyle change alone.

In the opinion of the experts, other possible applications of fenofibrate in diabetic patients are subclinical arteriosclerosis and being overweight or obese.39,40 A recent meta-analysis41 clearly demonstrated a fall in the rate of CV disease in patients with high triglyceride levels and low HDL-C treated with fibrates.

Fenofibrate may be of particular benefit to patients with cardiometabolic risk. In an animal model, PPAR-alpha activation reduced visceral adiposity, had beneficial effects on pancreatic beta cells and improved the peripheral action of insulin.42

Beyond its beneficial effects on the lipid profile, fenofibrate is also administered for other PPAR-alpha-mediated effects, such as the reduction of fibrinogen and proinflammatory mediators, or improved vasodilatation.43 These benefits may be related to the improvement in microvascular complications experienced by diabetic patients: retinopathy (delaying the need for laser photocoagulation), neuropathy (reducing the need for non-traumatic amputations) and nephropathy (reducing albuminuria).44–46 In this regard, fenofibrate has been approved in Australia to control diabetic retinopathy progression and blood pressure, as well as for glycaemic and lipid control.47

In which risk categories is fenofibrate used?Fenofibrate should be used in patients with high or very high CV risk specifically to control triglycerides and HDL-C4 (Fig. 4). In patients with moderate risk, more radical lifestyle change should be considered before pharmaceutical therapy.

Experts recommend the use of fenofibrate in patients with AD and high cardiometabolic risk, as well as in those with AD and subclinical arteriosclerosis.

It should also be considered that the most pertinent use of fenofibrate will be in secondary prevention (for example, patients with controlled or uncontrolled LDL-C taking maximum doses of statins or a statin plus ezetimibe, but with elevated levels of triglycerides with or without low HDL-C). Its use may also be considered in primary prevention in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Combination therapy in a single tablet could be very effective in increasing treatment adherence.

However, the distinction between primary and secondary prevention is sometimes arbitrary as arteriosclerosis is a continuous process.23 As such, calculating individual CV risk, including in diabetic patients in whom damage or involvement of the target organs may prove to be the differentiating factor, may be more relevant.38

What is fenofibrate's long-term safety profile?Expert consensus is that fenofibrate is a well tolerated drug with no significant concerns over its safety. It is better tolerated than gemfibrozil, which should not be administered with statins due to the risk of myotoxicity.24

Although it has been found that its administration may coincide with increased plasma creatinine levels, it has not been proven that this is due to impaired kidney function.48 This increase is reversible once the drug is withdrawn,49 and it has also not been shown to increase the incidence of advanced kidney disease.20 In general terms, fenofibrate should not be administered to patients with advanced kidney failure (eGFR<30ml/min) and should be used with caution in patients with moderate kidney failure (eGFR between 30 and 60ml/min).50

Muscular symptoms should also be monitored, together with liver and kidney function, particularly in patients with a history of symptoms induced by lipid-lowering drugs.50

Although increased homocysteine levels have also been reported, the treatment is nevertheless beneficial to patients as this has no impact on CV risk.51

ConclusionLipid abnormalities characteristic of AD contribute to residual CV risk in a significant proportion of patients in whom LDL-C has been adequately controlled with statins. Control of this problem is clearly not sufficient and awareness of this issue therefore needs to be raised. It is important to note that the primary treatment objective in patients with AD is LDL-C or, failing that, non-HDL-C, followed by triglyceride levels. AD treatment includes optimising lifestyle and the administration of statins, either alone or in combination with ezetimibe. In the event of persistently high triglycerides, fenofibrate may also need to be added. The statin-fenofibrate combination has a favourable risk-benefit profile. In patients with severe hypertriglyceridaemia (≥5.6mmol/l/500mg/dl), the primary objective is to lower triglyceride levels with fenofibrate to prevent pancreatitis.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Atherogenic Dyslipidaemia Working Group of the Spanish Society of Arteriosclerosis: Juan F. Ascaso, Mariano Blasco, Ángel Brea, Ángel Diaz, Antonio Hernández Mijares, Teresa Mantilla, Jesús Millán (Coordinator), Juan Pedro-Botet and Xavier Pintó.

European Group of Experts: Roberto Ferrari, Carlos Aguiar, Eduardo Alegria, Riccardo C. Bonadonna, Francesco Cosentino, Moses Elisaf, Michel Farnier, Jean Ferrières, Pasquale Perrone Filardi, Nicolae Hancu, Meral Kayikcioglu, Alberto Mello e Silva, Jesus Millan, Željko Reiner, Lale Tokgozoglu, Paul Valensi, Margus Viigimaa, Michal Vrablik, Alberto Zambon, José Luis Zamorano and Alberico L. Catapano.

Please cite this article as: Grupo de trabajo de Dislipemia Aterogénica de la Sociedad Española de Arteriosclerosis y Grupo Europeo de Expertos. Recomendaciones prácticas para el manejo del riesgo cardiovascular asociado a la dislipemia aterogénica, con especial atención al riesgo residual. Adaptación española de un Consenso Europeo de Expertos. Clin Invest Arterioscler. 2017;29:168–177.

The names of the components of the Atherogenic Dyslipemia Working Group of the Spanish Society of Atherosclerosis and the European Expert Group are related in Annex.