We present the adaptation for Spain of the updated European Cardiovascular Prevention Guidelines. In this update, greater stress is laid on the population approach, and especially on the promotion of physical activity and healthy diet through dietary, leisure and active transport policies in Spain. To estimate vascular risk, note should be made of the importance of recalibrating the tables used, by adapting them to population shifts in the prevalence of risk factors and incidence of vascular diseases, with particular attention to the role of chronic kidney disease. At an individual level, the key element is personalised support for changes in behaviour, adherence to medication in high-risk individuals and patients with vascular disease, the fostering of physical activity, and cessation of smoking habit. Furthermore, recent clinical trials with PCSK9 inhibitors are reviewed, along with the need to simplify pharmacological treatment of arterial hypertension to improve control and adherence to treatment. In the case of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and vascular disease or high vascular disease risk, when lifestyle changes and metformin are inadequate, the use of drugs with proven vascular benefit should be prioritised. Lastly, guidelines on peripheral arterial disease and other specific diseases are included, as is a recommendation against prescribing antiaggregants in primary prevention.

Presentamos la adaptación para España de la actualización de las Guías Europeas de Prevención Vascular. En esta actualización se hace mayor énfasis en el abordaje poblacional, especialmente en la promoción de la actividad física y de una dieta saludable mediante políticas alimentarias y de ocio y transporte activo en España. Para estimar el riesgo vascular, se destaca la importancia de recalibrar las tablas que se utilicen, adaptándolas a los cambios poblaciones en la prevalencia de los factores de riesgo y en la incidencia de enfermedades vasculares, con particular atención al papel de la enfermedad renal crónica. A nivel individual resulta clave el apoyo personalizado para el cambio de conducta, la adherencia a la medicación en los individuos de alto riesgo y pacientes con enfermedad vascular, la promoción de la actividad física y el abandono del hábito tabáquico. Además, se revisan los ensayos clínicos recientes con inhibidores de PCKS9, la necesidad de simplificar el tratamiento farmacológico de la hipertensión arterial para mejorar su control y la adherencia al tratamiento. En los pacientes con diabetes mellitus 2 y enfermedad vascular o riesgo vascular alto, cuando los cambios de estilo de vida y la metformina resultan insuficientes, deben priorizarse los fármacos con demostrado beneficio vascular. Por último, se incluyen pautas sobre enfermedad arterial periférica y otras enfermedades específicas, y se recomienda no prescribir antiagregantes en prevención primaria.

The 2016 European Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention were adapted in Spain by the Spanish Interdisciplinary Vascular Prevention Committee (CEIPV).1,2 In this document we present the 2020 update of these guidelines,3 which place greater emphasis on population approaches and disease-specific interventions.

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2015 showed that vascular disease (VD) remains a major public health problem worldwide,4 causing one third of deaths, with a predominance of deaths of atherosclerotic origin (coronary heart disease and stroke) and major disability. In Europe, although the trend in cardiovascular mortality rates is decreasing, morbidity is increasing, due to increased survival and ageing of the population.5

In Spain, although mortality from VD decreased from 34.9% in 2000 to 28.3% in 2018, it remains the leading cause of death.6 In 2016, the diseases leading the mortality ranking were coronary heart disease (14.6%), dementia (13.6%), and cerebrovascular disease (7.1%).7 Back and neck pain is the main cause of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), followed by coronary heart disease and dementia.7 The most important risk factors, due to their prevalence and impact on health, are smoking, high blood pressure (BP), high body mass index (BMI), alcohol consumption and hyperglycaemia.7

In the last decade, the concept of VD has evolved into the concept of vascular health (VH).8 Just ten years ago, the American Heart Association (AHA) and other international bodies introduced a new approach to improve VH, based on seven metrics (Life's Simple 7-LS7),9 of which four are health behaviours (normal BMI, non-smoking, healthy diet and physical activity) and three are risk factors based on optimal levels without pharmacological treatment of: cholesterol (<200 mg/dL), blood pressure (BP) (<120/<80 mmHg) and fasting blood glucose (<100 mg/dL). In the Spanish cohort of the PREDIMED10 study, with 7447 patients followed for 4.8 years, the higher the number of appropriate metrics, the lower the incidence of vascular events.

Strategies for cost-effective primary prevention of VD include primary prevention and identification of high-risk subjects.

Vascular riskWhich risk tables to use?We can estimate the absolute risk of developing VD over a 10-year period using risk tables or risk functions. For example, if a person's vascular risk (VR) is 6%, out of 100 people with their risk profile, six will develop a VD in the next 10 years. The European guidelines recommend SCORE for low or high-risk countries; they also recommend using national tables if correctly calibrated and validated.11

In the Spanish population, the SCORE tables for low-risk countries considerably overestimate the risk12,13 and their predictive capacity in patients with hypercholesterolaemia is limited.14 There is experience of recalibrating the 1998 Framingham equation with REGICOR15 and its validation in the cohorts of the VERIFICA study (validity of an adaptation of the Framingham cardiovascular risk function).16 The FRESCO17 tables were also developed from 11 Spanish cohorts and are accurate and reliable for predicting the risk of coronary heart disease and stroke at 10 years in the population aged 35–79 years. It is very important to recalibrate the tables used, adapting them to changes in the prevalence of risk factors and the incidence of VD. For example, using REGICOR slightly overestimates the risk in the FRESCO population.17

There are other important aspects in risk assessment. The first is the need to develop risk tables for patients who have already had VD, given the emergence of new and expensive treatments, such as proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9) inhibitors, and because risk predictors may vary greatly from those of primary prevention. Then there is the use of lifetime vascular risk in young patients, from 18 to 75 years of age, for which a calculation model has been developed from the Spanish working population (IBERLIFERISK), to calculate the risk from 18 to 75 years of age,14 and work is being done to validate it externally. And third is the challenge of risk communication and shared decision-making in clinical practice. In addition to vascular age and relative risk, new approaches have been published to calculate long-term benefit and life years gained with drugs to control dyslipidaemia and hypertension (HTN), antiaggregant agents and smoking cessation.18,19

Non-conventional risk factorsThe tables include a small number of risk factors, but others have been described that could be useful in modifying the risk calculated with the tables.20

For a risk factor to be considered useful a) it must be able to adequately reclassify risk, b) there must be no publication bias, c) it must be a cost-effective measurement. European guidelines include socioeconomic status, family history of premature VD, (central) obesity, ankle-arm index, presence of carotid artery plaque and coronary calcium score.1 The American guidelines include these and other risk modifiers.21 However, there is limited evidence on their usefulness in clinical practice. Intracoronary calcium is the biomarker with the highest predictive ability, but it is considered unnecessary additional screening due to cost-benefit ratio and radiation risk.20

Other risk markersGenetic and epigenetic: there are studies on the predictive capacity of genetic risk scores22 and to identify individuals who respond better to statin therapy, but cost-effectiveness is not well defined.23 Epigenetic (DNA methylation, non-coding RNA and histones) and VD-related gene expression markers have also been studied, but their clinical utility is unproven.24

Psychosocial: Depression increases the risk of coronary heart disease by mechanisms that favour the progression of atherosclerosis and microvascular remodelling.25 Depression and anxiety are also more frequent in patients who have developed coronary heart disease.26 Traumatic experiences in childhood and adolescence, such as physical and psychological abuse or sexual abuse, are associated with increased risk of metabolic disturbances in adulthood.27 These variables are included in the QRISK3 risk function.28 Therefore, the diagnosis of these psychosocial disturbances needs to be accompanied by the detection and control of VR factors.

Imaging methods: The 2019 US guidelines include intracoronary calcium measurement as a recommendation (level IIa) to reclassify VR in individuals from intermediate to high risk if the Agatston coronary calcium score is ≥100 units or ≥75th percentile of their age and sex group, or from intermediate to low risk if the score is 0.21 However, the correlation between coronary calcium and degree of stenosis is weak, does not provide direct information on the amount of atheroma plaque, and does not detect the presence of non-calcified plaques.

In the SCOT-HEART clinical trial, the group in which intracoronary calcium was measured presented a significant reduction in coronary events.29 However, there are no clinical trials that have examined the usefulness of calcium measurement in asymptomatic individuals.

Clinical conditions influencing vascular riskDiabetes mellitus: VD is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in people with diabetes, a condition that itself confers an elevated VR, which varies depending on glycaemic control, comorbidities and the type, duration, and age at diagnosis of diabetes. In the type 2 diabetes (DM2) population, other VR factors, such as obesity, HTN or atherogenic dyslipidaemia, frequently co-exist, and there is ample evidence of the benefits of risk factor (RF) reduction through multifactorial interventions. A diagnosis of DM2 in young individuals is associated with higher mortality, mainly due to early-onset VD,30-32 probably due to a worse cardiometabolic risk profile at time of diagnosis.30,33 Hence the importance of DM2 prevention in young people and of considering the age of diabetes onset to stratify risk and decide on the timing and intensity of risk factor (RF) interventions.

People with type 1 diabetes (DM1) are at high risk of mortality and premature VD,34 but the underlying mechanisms are poorly understood. After age, glycaemic control as assessed by time-weighted mean glycated haemoglobin A1c appears to be the most relevant factor, while other RF such as BP, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) become important 15–20 years after diagnosis.35-37 In addition, studies demonstrate the long-term beneficial effects of optimising glycaemic control through intensive therapy,38 while evidence for the benefits of reducing other RF in DM1 is scarce. Age at DM1 onset is also an important determinant of survival and VD.39 Compared to those diagnosed between the ages of 26–30 years, DM1 diagnosed before the age of 10 years increased the risk of acute myocardial infarction fivefold, with a higher loss of life years for women (17.7 vs. 10.1 years) and men (14.2 vs. 9.4 years). This justifies an early cardioprotective approach in these young patients where the absolute risk is still low.

Accurate risk stratification is a key element to select appropriate prevention strategies. In subjects with diabetes, risk equations are of limited use and have often not been validated, especially in those under 40 years of age with low short-term but high lifetime VR. In these, an alternative would be the estimation of lifetime VR, but there is no consensus on how to apply this. Current recommendations offer different approaches to vascular risk stratification in patients with diabetes.40,41

Chronic kidney disease: Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is of increasing impact on population health as a cause of morbidity and mortality and as a risk factor for VD,42-44 influencing treatment recommendations to reduce the risk of vascular events.45-47 Measurement of kidney function by estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and quantification of urinary albumin clearance enable the stratification of VR,42 since decreased eGFR and the presence of albuminuria increase the risk of vascular events.28,48-52

In the European guidelines,1 CKD is considered a risk factor for vascular events independent of other RF. They establish that patients with an eGFR less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2 should be considered at very high risk and those with an eGFR between 30 and 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 at high risk.

QRISK algorithms are models developed in the UK population to predict the 10-year risk of de novo VD and are recommended by the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence as a decision-making tool to reduce the risk of vascular events.53 The first QRISK model in 2007 was updated in 2008 (QRISK2), incorporating CKD stages 4 and 5 as predictor variables. QRISK2 was later updated to QRISK3,28 which incorporates new variables to improve prediction, adding stage 3 to the QRISK2 diagnostic criteria.

Compared to other models for predicting the risk of developing VD, such as SCORE11 or the American model,54 QRISK3 has the advantage that it considers the presence of CKD stage 3, 4 or 5 as a binary factor for estimating VR. However, QRISK3 is an algorithm derived from real practice primary care records in the UK population, with missing data that are treated by imputation, which requires external validation of its usefulness in other populations.

Influenza: the incidence of acute myocardial infarction increases during the influenza season and influenza vaccination is recommended for secondary prevention of VD.3

Periodontitis: a link between periodontal disease and myocardial infarction has been observed,55 but evidence on the effects of its treatment in secondary prevention is of low quality56 and non-existent in primary prevention.

Autoimmune diseases: an increased risk has been observed in patients with inflammatory autoimmune diseases, especially rheumatoid arthritis.3

Other clinical conditions associated with VD: obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, cancer, erectile dysfunction, and migraine.3

Other relevant groupsYoung peopleThis section refers to those <40 years of age. Currently, there is a trend in younger adults to have increased overall VR, due to a higher prevalence of overweight/obesity, diabetes, and toxic habits (smoking, opioids, cocaine, anabolic agents, and electronic cigarettes).57 Obesity is the main RF to be addressed. In Spain, the prevalence of overweight is very high in the general population (57.8%) and in patients with ischaemic heart disease (77.3%), accounting for almost 50% of coronary events.58 In the population aged three to 24 years, the prevalence of excess weight exceeded 30%.59

In addition, elevated LDL-C levels in young adults should raise the suspicion of familial hypercholesterolaemia, the most common monogenic disease in humans, with a prevalence of 1:130−250 individuals. This would help to detect the condition and provide an opportunity to improve the current situation of underdiagnosis and undertreatment.60,61

Finally, diastolic BP is a better predictor of vascular events than systolic BP in individuals <50 years of age, while from middle age onwards it tends to decrease due to arterial stiffness. Furthermore, masked HTN is more common in young adults and is associated with male sex, smoking, alcohol consumption, anxiety, physical and occupational stress,62 leading to undertreatment of HTN and increased VR. The presence of target organ damage in young patients with grade 1 HTN indicates HTN-mediated damage and the need to initiate pharmacological treatment to achieve a target BP ≤ 130/80 mmHg.47

Older adultsThe treatment of RF in older adults (>75 years) should be tailored to the patient, due to the paucity of scientific evidence, associated comorbidity, frailty and shorter life expectancy, concomitant medication, and patient preferences. This age group represents 17.4% of the European population (about 64 million inhabitants); this proportion will double by 2050.63

The classical RF do not predict the risk of death in this segment of the population.64,65 In a Belgian cohort of people over 80 years of age, frailty was associated with the risk of total and cardiovascular mortality, while the classical RF had no predictive value.66

Systolic BP increases progressively with age, especially from the age of 50 years onwards, with a prevalence of hypertension in those over 70 years of age exceeding 70%.67,68 Systolic BP > 160 mmHg is associated with increased mortality in the elderly, but caution should be exercised in intensifying treatment, as the association is even stronger with systolic BP < 120 mmHg. The threshold for initiating pharmacological treatment in patients over 80 years is considered a systolic BP ≥ 160 or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg. European guidelines recommend a target systolic BP between 130−139 mmHg in those over 65 years of age, emphasising that a greater reduction may do more harm than good.69 In the very elderly with hypertension, it seems prudent to start treatment with monotherapy and, if combination therapy is required, to start with lower doses.

In the older adult population, it is important always to consider biological rather than chronological age, to monitor the risk of hypotension, detect adverse effects, assess renal function frequently, individualise treatment, avoid iatrogenesis and take patient preferences into account.70

The prevalence of DM2 > 75 years is around 30% and, of these cases, 50% have VD or target organ damage. Hyper- and hypoglycaemias in this population present insidiously and clinically atypically, aggravating geriatric syndromes (falls, incontinence, depression, dementia, etc.). Therefore, the target glycated haemoglobin will depend on the patient’s degree of frailty, ranging from <7.5% in healthy older adults to <8.5% in cognitively impaired, dependent older adults or those with limited life expectancy.48 Older adults with diabetes are frequently over-treated and therefore considering de-intensifying treatment with safe and less complex regimens (with lower risk of hypoglycaemia, lower burden of care, better tolerability, and no drug interactions) is recommended.71

There is limited information on the efficacy of statins in reducing VD in the older adult. The relative risk reduction of cardiovascular events attenuates with age, both in secondary and primary prevention, where statins are no longer effective in patients >70 years.72 In the Physician's Health Study cohort, people over 70 years of age on statin therapy had lower mortality at seven years of follow-up, but no differences in cardiovascular events.73 However, a study in Catalonia showed that initiation of statin treatment in those over 75 years of age only had vascular and mortality benefits in diabetics aged 75–80 years.74 Another study showed that in French patients aged 75 years without VD who had been taking statins for at least two years, discontinuation of treatment was associated with a higher incidence of admissions for vascular events.75 Therefore, the beneficial effect of statin treatment or discontinuation of statin therapy in those over 75 years of age without VD is unclear.

WomenMore women than men currently die from VD in Europe, but at more advanced age.76 SCORE tables suggest that VD is delayed by approximately 10 years. The risk of HTN or diabetes is higher in women with obstetric complications, such as pre-eclampsia, HTN or gestational diabetes.1 Pre-eclampsia also increases the risk in offspring.77 Other factors for VD are miscarriage and foetal death.78 In addition, the lifestyle of prospective parents influences the likelihood of having a healthy child by epigenetic mechanisms,79 and premature menopause, especially with early oophorectomy, is an important RF.80

Gender differences in vascular prevention are age dependent. Women are less likely than men to have vascular disease risk factors measured and recorded in primary care, and preventive medication is more frequently prescribed in older than in younger women.81 Although the percentage of female smokers is lower than that of male smokers, the risk of coronary artery disease is 25% higher in female smokers than in male smokers.82 Therefore, VR assessment in women should be individualised according to age, lifestyle, diet, smoking, menopause, etc., identifying and guiding the appropriate management of specific RF.

Ethnicity: VR varies considerably by ethnicity. The updated QRISK3 score estimates future risk of VD by race.28

How to intervene at the population level?Healthy dietGovernment restrictions and mandates. Providing healthy, sustainably produced food to a growing world population is an immediate challenge. Approximately 800 million people worldwide suffer from undernutrition and 2 billion from nutritional deficiencies and overweight, which contributes to a substantial increase in the incidence of diabetes mellitus and VD.83 Unhealthy diets cause a greater burden of disease and death than unsafe sex and the use of alcohol, drugs and tobacco combined.84

Due to the high prevalence of obesity the current generation of children may have a shorter life expectancy than their parents. In EU countries, between seven and eight million people under the age of 15 are overweight and 800,000 are severely obese85; while in Spain around 700,000 children under the age of 14 are obese86 and between 100,000 and 200,000 severely obese,87 due to their exposure to the marketing of unhealthy foods.85,88 The global food system urgently needs to be changed. A global shift from current diets to healthy diets based on frequent consumption of vegetables, fruits, wholegrain flours, pulses, nuts, and unsaturated fats; moderate consumption of fish and poultry; and little or no red and processed meats, added sugars, refined flours and starchy vegetables, would prevent an estimated 11 million deaths per year, representing a reduction in overall mortality of around 20%.57

On 24 April 2019, the EU adopted a regulation that set a maximum limit of industrially produced trans fats of 2 g per 100 g of fat.89 The World Health Organisation (WHO), the EU and UNICEF are calling on governments to control the advertising and marketing of processed foods and sugary drinks to protect children's health.90-92 In June 2019, the European Commission highlighted the need for policy recommendations to reduce sugar intake, with a special focus on children, such as taxes on sugary drinks.93

Labelling and information. Different front-of-pack labelling schemes (traffic light, keyhole and Nutriscore) have been promoted in several European countries.94 The Nutriscore, based on a colour and letter code from A to E, has already been introduced in France and Belgium,95 while countries such as Spain and Portugal are considering its introduction.

Food policies in Spain. Nutrition experts from the Spanish Society of Epidemiology propose five priority policies - PODER - to reverse the epidemic of obesity and related non-communicable diseases by creating healthy food environments,96 which the Healthy Eating Alliance are also calling for97:

- •

P (Publicidad (Advertising)): regulation of the advertising of unhealthy foods and beverages to minors by all media, and prohibition of sponsorship of congresses or sporting events and endorsements by scientific or professional health associations.

- •

(Offer): promotion of a 100% healthy offer in vending machines in educational, health and sports centres.

- •

D (Demand): implementation of a tax of at least 20% on sugary drinks, accompanied by subsidies or tax reductions on healthy foods and the availability of drinking water at zero cost in all public centres and spaces.

- •

E (Etiquetado (Labelling)): effective implementation of the Nutriscore through incentives, regulation, and public procurement mechanisms.

- •

R (Reformulation): renewing reformulation agreements with industry, with more ambitious and enforceable targets.

The five proposed interventions, successfully implemented in other countries, will help raise public awareness and have a positive impact on health and the economy by reducing the health costs of obesity and increasing labour productivity. These measures should be part of a major transformation of the food system, with agri-food policies that promote the sustainable production of healthy food.

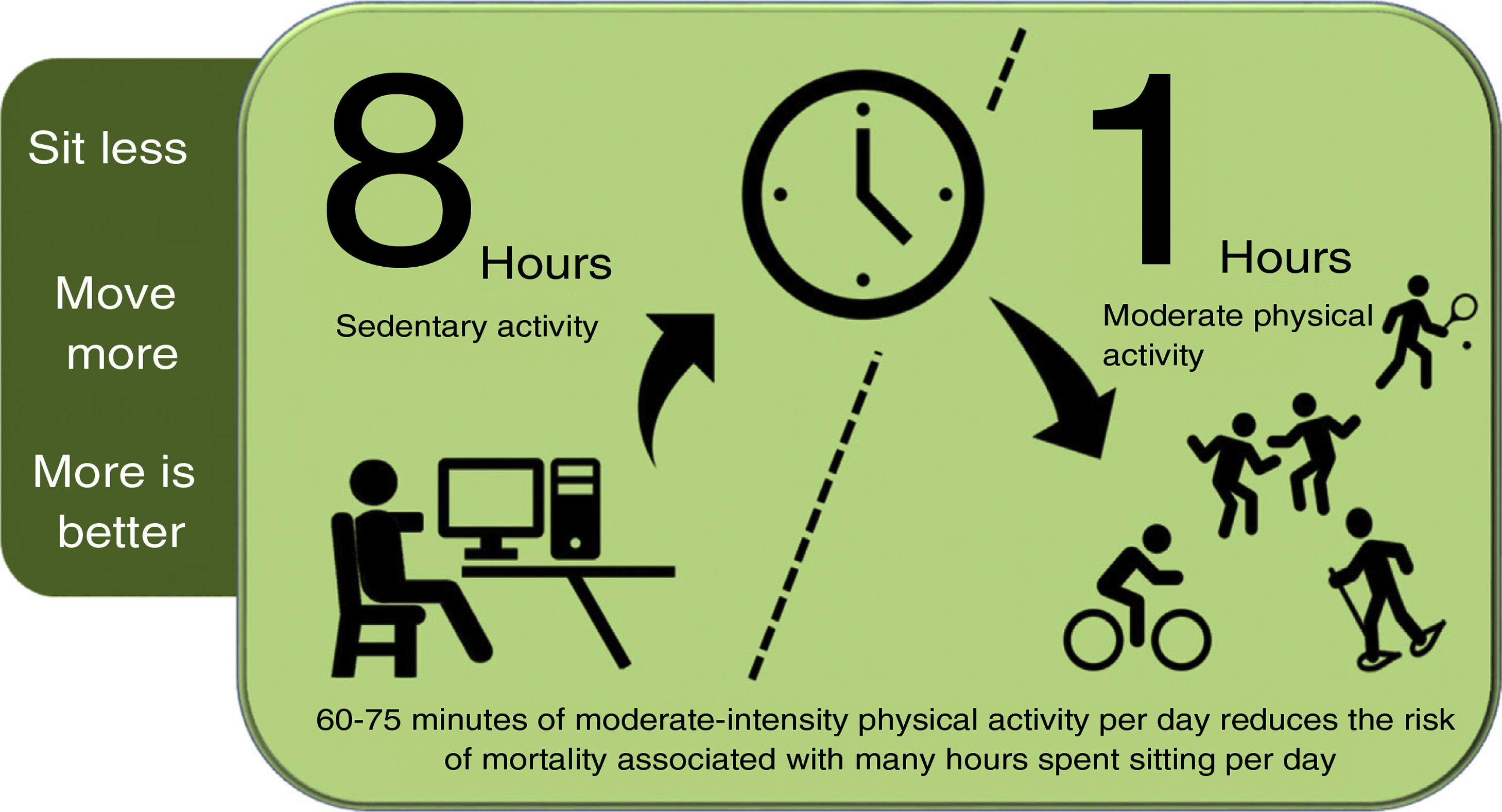

Promoting physical activityPhysical activity should be introduced into people's (active) lifestyles: sitting less, moving more, and exercising more. There is a direct association between time spent sitting per day, VD incidence and mortality and all-cause mortality98,99; while higher levels of physical activity reduce cancer and VD mortality.100 The risk associated with sitting for eight or more hours a day can be offset, but not eliminated, by 60−75 min of moderate physical activity per day (Fig. 1).101

Physical activity to reduce the risk of mortality due to sedentary lifestyle.

Compiled by the authors, based on reference.101

For people to move more, they should reduce time spent sitting at work, increase moderate activity at work, use active transport, and take some physical exercise. Cardiorespiratory fitness is the best predictor of mortality and vascular morbidity and the most modifiable protective RF for VD.102 Physical exercise is beneficial in preventing diabetes and coronary heart disease, rehabilitation after stroke and treatment of heart failure, and is therefore considered a "polypill" with a multisystemic effect and low cost.103

Intervention plan with a population focus. Physical activity should be integrated into the environments in which people live, work and play. Physical activity promotion policies should be part of an ecological model of health, within the relationship systems in which human behaviour takes place: microcontext (home, school, community, health centre), mesocontext (relationships between the previous contexts, community, neighbourhoods, etc.) and macrocontext (culture, socio-economic levels, urban location, etc.).104 A population-based approach to policy, targeting the least physically active groups, can reduce inequalities by age, gender, socio-economic status, geographic location and physical activity domains, and should be complemented by actions at the individual level. The WHO, within its GAPPA (Global Action Plan for Physical Activity) strategy, highlights four strategic objectives: a) active societies, b) active environments, c) active people and d) active systems.105

Community-based campaigns. Campaigns at community level that utilise close and intensive contact with most of the target population over time can increase physical activity across the population.106 These campaigns should include educational, recreational, work, primary care, community, and neighbourhood settings, offering convenient locations to reach different target groups with strategies tailored to each group. Multi-component interventions in kindergartens and schools are effective in promoting physical activity in and from school settings.106,107

Environment and policy. We need urban planning where sustainability and physical and social well-being are paramount. Motivational stimuli at the decision point encourage active choices, such as taking the stairs.108 Urban environments and infrastructure that promote walking and cycling (parks, cycle paths, footpaths, and other green spaces) and access to gyms or sports facilities increase physical activity levels at all ages. School-based interventions aimed at reducing TV time or other screen-based activities and workplace interventions are effective in reducing sedentary behaviours.108 The WHO recognises the need to prioritise physical activity in cities as part of daily lifestyle.109 Providing healthy routes from municipalities is an excellent strategy to promote an active lifestyle among residents and visitors.110

Smoking bansSmoking is the primary cause of preventable death worldwide.111 Non-smokers exposed to cigarette smoke have up to twice the 10-year risk of cardiovascular disease.112 The prevalence of smoking in Spain, with 29% of smokers in the population over 14 years of age, is higher than the European average.113

Since 181 countries ratified the action plan of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, only high-income European countries have reduced consumption, while consumption is increasing in low- and middle-income countries,114 possibly because of their limited resources to regulate the tobacco industry, whose activities demand a more forceful response. The most effective strategy to prevent and reduce smoking is to increase the price of tobacco products.110 Other effective measures include smoke-free laws and policies, marketing restrictions, advertising bans, strong media campaigns and access to cessation services.115 These measures, which need to be rigorously enforced through legislation, have substantially reduced smoking prevalence in high-income countries.116 Unfortunately, in Austria there has been a move in the opposite direction: the smoking ban scheduled for May 2018 in all bars and restaurants was recently revoked by lawmakers of the new ruling coalition.117

In Spain, the 2005 and 2010 anti-smoking laws do not seem to have had a significant impact on tobacco consumption, observed to have been reducing over time before the regulation came into force, which may reflect the combined influence of all smoking prevention and control policies developed in the last decades, together with the influence of the financial crisis.113

There are actions pending to denormalise smoking in Spain. First, plain packaging and prevention campaigns. Second, taxation policies, equalising the price of all tobacco products, and the creation of new smoke-free spaces, especially to avoid the exposure of minors and other vulnerable groups (private homes and vehicles). Third, applying smoke-free regulations to electronic cigarettes on an equal footing with traditional tobacco products. And finally, there is an urgent need to extend and systematise cessation support, to fund pharmacological interventions and to train health professionals in effective smoking cessation interventions.113

Air pollutionThe most used indicators of air pollution are concentration of NO2 and particulate matter smaller than 10 μ (PM10) or 2.5 μ (PM2.5) in suspension. Air pollution increases the risk of long-term VD and can trigger acute events in the short term (24−72 h). This increased VR appears to be mediated by regulation of blood pressure, thrombosis, inflammation, and endothelial function.118

The direct relationship between the level of exposure to particulate matter in the air (PM10 and PM2.5) and total, cardiovascular and respiratory mortality is almost linear.119 Air pollution, especially exposure to small particles PM2.5, is responsible for 790,000 deaths per year in Europe, primarily of vascular origin, resulting in a reduction in life expectancy of about 2.2 years.120 In the short term, studies in Spain have also reported a relationship between PM10 and PM2.5 levels and hospital admissions for acute coronary syndrome (ACS).121

Exposure to noise, especially traffic-related, is also associated with increased all-cause and vascular mortality.122 Exposure to small particulate matter (PM10-PM2.5), noise and, in our country, Sahara Desert dust have a synergistic effect on VR.123

Public transport and urban planning policies designed to reduce air pollution and noise, increased green spaces and physical activity through active transport are strategies that contribute to vascular disease prevention.124 Although there are initiatives in several Spanish cities to control air pollution levels nationally and globally, the measures implemented are not very effective. It is necessary to assess whether the measures are being implemented correctly or whether other, more effective, and sustainable strategies need to be defined to achieve better quality of the air we breathe.125

How to intervene on an individual basis?BehaviourThe use of information technology (ICT) for the prevention of VD is increasing. A clinical trial to achieve behavioural change in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) showed favourable results on BMI, waist circumference, daily intake of vegetables and physical activity through telephone counselling.126 Personalised internet-delivered support for behaviour change may have favourable outcomes, but more studies are needed to draw firm conclusions.127

AdherenceAdherence to medication in high-risk individuals and patients with VD is low.128 It is recommended to identify causes, tailor interventions, and simplify therapeutic regimens. There is low quality and inconclusive evidence that mobile phone-based interventions improve medication adherence and have favourable effects on BP and LDL-C in primary prevention of VD,129 and there is insufficient evidence in secondary prevention.130

Physical activity and sedentary lifestyleThere is an inverse dose-response relationship between moderate-intense aerobic activity and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke and heart failure in both primary and secondary prevention.131-133 High-intensity interval training can improve insulin sensitivity, BP and body composition in a similar way to continuous aerobic physical activity training, especially in obese or overweight adults.134 There is a dose-response association between sedentary behaviour and VD and all-cause mortality, vascular events and DM2.135

The most effective interventions to increase physical activity in the general population or those with DM2 are based on theories of behavioural change, teaching skills to incorporate physical activity into daily routines, setting physical activity goals and self-monitoring with pedometers or accelerometers.136,137 Mobile phone applications have proved useful in children and adolescents.

Smoking cessation: the role of electronic cigarettesMost e-cigarettes contain nicotine, exposure to which can damage the developing brain and affect learning, memory, and attention during adolescence; they also include other substances harmful to the body: flavourings, volatile organic compounds, heavy metals, and nitrosamines.138 E-cigarette users are less likely to quit smoking than non-users.139 There is no conclusive evidence therefore on the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in reducing smoking.140

WeightThere is increasing evidence for the beneficial effect of weight reduction with calorie restriction and dietary interventions in the management of diabetes in primary care.141

NutritionHigh consumption of carbohydrates is associated with an increased risk of total mortality,142 while consumption of virgin olive oil, fruits, vegetables, and legumes reduce total and vascular mortality.143 Reducing the consumption of red meat is recommended because of its impact on the environment and increased risk of colon cancer and VD, although there is debate regarding the evidence on VR.144

Most studies show that moderate alcohol consumption is associated with a lower risk of VD morbidity and mortality,144 although the association may be due to methodological problems. The threshold for lower risk of all-cause mortality is between 0 and 100 g per week, i.e., no level of alcohol consumption is associated with better health.145 These data support the recommendation not to consume alcohol and, if consumed in moderation, not to exceed the above-mentioned thresholds.

Lipid monitoringAs this is an update, the authors only provide data from the latest clinical studies with PCSK9 inhibitors and omega-3 fatty acids.

PCSK9 inhibitorsPCSK9 inhibitors further reduce non-fatal vascular events through their LDL-C lowering effects.146,147 In the FOURIER study,146 treatment with evolocumab in combination with moderate-high intensity statins in patients with stable VD, over two years of follow-up, reduced the composite incidence of death, myocardial infarction, stroke and admission for unstable angina or coronary revascularisation regardless of baseline LDL-C levels.146 In the ODYSSEY study,147 in patients with a recent coronary syndrome, a similar decrease in the composite incidence of coronary death, non-fatal myocardial infarction, fatal/non-fatal ischaemic stroke and unstable angina requiring hospitalisation was obtained in the alirocumab treatment arm, with greater benefit in patients with LDL-C > 100 mg/dL. In addition, the SPIRE programme with bococizumab, although discontinued due to a progressive lack of efficacy, showed a beneficial impact on vascular events.,148 Different sub-analyses of the FOURIER and ODYSSEY studies have provided further evidence of the vascular benefits of PCSK9 inhibitors in different clinical situations, polyvascular patients for example, especially with peripheral artery disease149,150 and with elevated lipoprotein (a) concentrations.151,152

It is worth mentioning that PCSK9 inhibitors have shown positive effects on atheroma plaque composition and regression,153 do not increase the incidence of diabetes, worsen carbohydrate metabolism,154 have no adverse effects on cognitive function,155,156 and do not increase the risk of cataracts157 or cancer.158 However, studies with long-term follow-up are needed to confirm their safety profile.

The main barrier to the use of PCSK9 inhibitors is economic, a key factor in terms of public health. If we consider the effective reduction of LDL-C and vascular events with statins in monotherapy or in combination with ezetimibe, the inherent costs of the different drug therapies and the limited long-term safety data with PCSK9 inhibitors, it is likely that these drugs are only indicated in patients with very high VR,159 or, if prices were lower, in a wider range of patients with high VR.160 For these reasons, several scientific societies have published recommendations for the use of these drugs in patients with a better cost-benefit ratio.161

Omega-3 fatty acidsThe effect of omega-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular prevention is debated.162,163 It is possible that the use of the current therapies may result in less benefit from omega-3 fatty acids than when omega-3 fatty acids are evaluated without these therapies. In addition, their cardiovascular benefits may vary according to the severity of the cardiovascular disease.164 Finally, some cardioprotective effects of omega-3 fatty acids require high doses: ≥2g/day to reduce triglycerides and diastolic BP, and higher doses for antithrombotic effects.165

In the REDUCE-IT trial, high doses of icosapent ethyl (4 g/day) reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events by 25% in subjects with stable VD or diabetes and LDL-C concentrations <100 mg/dL and triglycerides between 150 and 499 mg/dL.166 These cardiovascular benefits mainly related to baseline risk and other non-triglyceride-dependent effects.167

Earlier this year, the STRENGTH trial was stopped due to its low likelihood of demonstrating a benefit. The OCEAN-3 trial is currently underway to determine whether reducing triglyceride-rich lipoproteins and their remnants in statin-treated patients provides an additional reduction in VR.

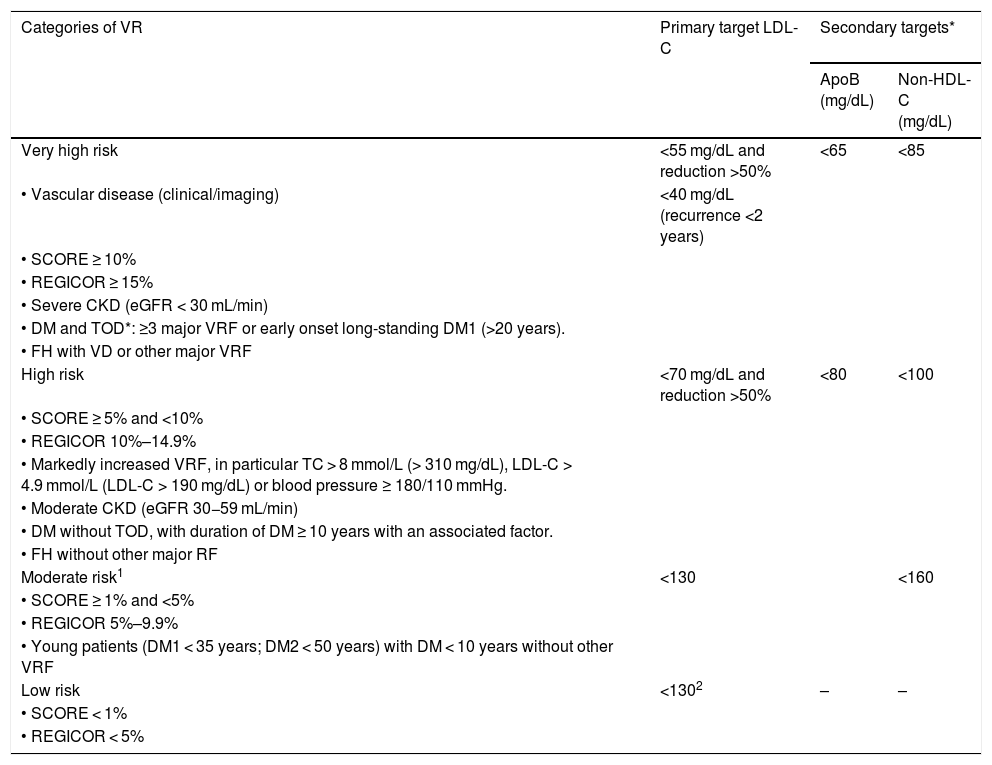

Table 1 shows the VR categories and lipid control targets proposed by the recent European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias and adapted by the CEIPV.42 The CEIPV wishes to highlight and qualify some aspects:

- •

LDL-C targets would be the same, regardless of the vascular territory affected; the important thing is to achieve an LDL-C reduction ≥50%.

- •

All patients with familial hypercholesterolaemia should be considered high risk, with LDL-C targets <70 mg/dL and LDL-C reduction >50%. Those with another associated risk factor or established VD, should be considered very high risk with targets of LDL-C < 55 mg/dL and reduction >50%.168

- •

Lifestyle changes are recommended in low-risk patients, and risk modifiers should be considered in moderate-risk patients to decide whether statin therapy is required.

- •

Lifestyle changes and maintaining LDL-C < 130 mg/dL are recommended for the general population.

Vascular risk categories and lipid control targets.

| Categories of VR | Primary target LDL-C | Secondary targets* | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ApoB (mg/dL) | Non-HDL-C (mg/dL) | ||

| Very high risk | <55 mg/dL and reduction >50% | <65 | <85 |

| • Vascular disease (clinical/imaging) | <40 mg/dL (recurrence <2 years) | ||

| • SCORE ≥ 10% | |||

| • REGICOR ≥ 15% | |||

| • Severe CKD (eGFR < 30 mL/min) | |||

| • DM and TOD*: ≥3 major VRF or early onset long-standing DM1 (>20 years). | |||

| • FH with VD or other major VRF | |||

| High risk | <70 mg/dL and reduction >50% | <80 | <100 |

| • SCORE ≥ 5% and <10% | |||

| • REGICOR 10%–14.9% | |||

| • Markedly increased VRF, in particular TC > 8 mmol/L (> 310 mg/dL), LDL-C > 4.9 mmol/L (LDL-C > 190 mg/dL) or blood pressure ≥ 180/110 mmHg. | |||

| • Moderate CKD (eGFR 30−59 mL/min) | |||

| • DM without TOD, with duration of DM ≥ 10 years with an associated factor. | |||

| • FH without other major RF | |||

| Moderate risk1 | <130 | <160 | |

| • SCORE ≥ 1% and <5% | |||

| • REGICOR 5%–9.9% | |||

| • Young patients (DM1 < 35 years; DM2 < 50 years) with DM < 10 years without other VRF | |||

| Low risk | <1302 | – | – |

| • SCORE < 1% | |||

| • REGICOR < 5% | |||

ApoB: apolipoprotein B; BP: blood pressure; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DM: diabetes mellitus; DM1: type 1 diabetes; DM2: type 2 diabetes; eGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate; FH: familial hypercholesterolaemia; LDL-C: low density lipoprotein cholesterol; non-HDL-C: non HDL-cholesterol; SCORE: Systematic Coronary Risk Estimation; TC: total cholesterol; TG: triglycerides; TOD: target organ damage (defined as microalbuminuria, retinopathy or neuropathy); VD: vascular disease; VRF: vascular risk factors.

Adapted from Mach et al.42

ApoB is recommended as an ideal alternative to LDL-C, particularly in people with high TG levels, DM, obesity, metabolic syndrome, or very low LDL-C levels. It can be used, if available, as the primary measure for screening, diagnosis, and treatment, and may be preferable to non-HDL-C in these groups of patients, although its low availability in our setting makes non-HDL-C the more operational option.

The most effective strategy to prevent VD in people with diabetes is multifactorial and comprehensive therapeutic intervention, with control targets for each modifiable risk factor. Lifestyle changes that help control body weight, through sustainable dietary changes and increased physical activity, are effective in the prevention of DM2, even with moderate weight loss (5%–10%)169 and, in subjects with diabetes, in improving glycaemic control, lipids and blood pressure.170,171 In the DIRECT trial, in subjects with DM2 of less than six years' duration not treated with insulin, 86% of participants who lost ≥15 kg had remission of DM2, compared to 34% of those with weight loss of 5–10 kg.172

A target HbA1c <7.0% (<53 mmol/mol) is recommended in most patients with DM2 or DM1. In frail patients, patients with severe comorbidities or high risk of hypoglycaemia or difficulty in recognising hypoglycaemia (asymptomatic hypoglycaemia, very young children), less stringent targets should be considered. Conversely, in patients with long life expectancy and low risk of hypoglycaemia, a target of HbA1c ≤ 6.5% (≤48 mmol/mol) can be set. In patients with DM2 with VD or high VR, when lifestyle measures and methamphetamine are insufficient, drugs with demonstrated vascular benefit (empagliflozin, dapagliflozin, canagliflozin, liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide) should be prioritised.173,174 Most patients with DM1 should be treated with multiple daily injections or continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion and frequent glycaemic monitoring. In children and adolescents, considering their higher relative risk of mortality and the lack of efficacy of complementary therapies, facilitating intensive glycaemic control (insulin pump, continuous glucose monitoring and closed-loop systems) is probably the most effective measure to help improve vascular prognosis.48

Antihypertensive drug therapy is recommended for people with diabetes and BP > 140/90 mmHg, with therapeutic targets of systolic BP ≤ 130 mmHg and diastolic BP < 80 mmHg. Lipid-lowering drugs, mainly statins, are recommended based on the patient's VR profile and LDL-C target. In patients with DM2 < 40 years or patients with DM1 of any age, it is difficult to determine when to initiate statin therapy, therefore current recommendations should be applied as per clinical judgement, considering age, history of glycaemic control, and the coexistence of genetic dyslipidaemia or other factors or conditions associated with increased VR, and patient preference.40,42,175

HypertensionIn this guideline update,1 and in the 2018 ESHC/ESH guidelines,47 HTN is defined as a systolic BP ≥ 140 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 90 mmHg, optimal BP as <120/80 mmHg, and normal-high BP as systolic BP between 130−139 mmHg and/or diastolic BP between 85−90 mmHg.

The ACC/AHA guidelines define HTN as clinical systolic BP ≥ 130 mmHg and/or diastolic BP ≥ 80 mmHg,46 but this would mean an increased prevalence of HTN in the adult population in Spain from 33.1% (95% CI 32.2%–33.9%) to 46.9% (95% CI 46.0%–47.8%),175 which would translate as a significant increase in the number of hypertensives to be treated or intensifying antihypertensive medication in the general population. However, VR increases steadily from BP levels >115/75 mmHg, therefore the optimal BP would be <120/80 mmHg, and the group with elevated normal BP represents a very prevalent subgroup of subjects in whom lifestyle changes should be implemented early to prevent progression to established HTN.

At the initial assessment BP should first be measured in both arms, as a BP difference between both arms >15 mmHg is associated with increased VR, and standing, with orthostatic hypotension being defined as a drop within the first three minutes of systolic BP ≥ 20 mmHg or diastolic BP ≥ 10 mmHg.47 Ambulatory BP measurements by ambulatory BP monitoring (ABPM) or self-measured blood pressure monitoring (SBPM) also need to be enhanced, as they correlate more closely with prognosis and target organ damage than clinical BP measurement, therefore their use is highly recommended as diagnostic in untreated subjects and for monitoring treatment effects and improving adherence. We currently have very convincing data from studies in our country in this regard and an excellent recent document on ambulatory BP measurement.62,176

The decision to initiate pharmacological treatment will depend on BP level, estimated VR based on other VR factors, target organ damage or the presence of established vascular or kidney disease.

Antihypertensive treatmentThe goal of antihypertensive therapy is to reduce vascular mortality and morbidity. To achieve this goal, all associated VR factors must be treated in addition to BP readings.

Due to the distribution of BP in the general population, mild or stage 1 hypertension (systolic BP 140−159 mmHg or diastolic BP 90−99 mmHg) accounts for 60% of hypertensives or 22% of the general population. In low-moderate risk stage 1 hypertensive subjects, the ESC/ESH guidelines advise three to six months of lifestyle changes to attempt control of HTN, while in stage 1 hypertensives with high VR, or stage 2 and 3 hypertensives they recommend starting concomitant pharmacological treatment from the outset. They also advise a time frame of three months to achieve control of HTN. A delay in the diagnosis or control of HTN results in an increased incidence of overall mortality.177 Therefore HTN control must be timely and diligent.178

The use of combination therapy in most hypertensive patients, preferably in a single tablet, is one strategy to improve control of HTN. The use of monotherapy as initial treatment would only be indicated in patients with low-risk stage 1 systolic HTN and systolic BP < 150 mmHg, older subjects (>80 years) or frail patients. Although the ESC/ESH guidelines recommend the use of a single tablet, in cases where triple therapy is necessary, the option of administering at least one of the antihypertensive drugs at night may also be advised, to achieve better control of nocturnal BP, especially in severe or resistant HTN.

The recommendations have been simplified to improve control of HTN and adherence to treatment: angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors and angiotensin II type 1 receptor blockers, combined with calcium antagonists or thiazide or thiazide-like diuretics (chlorthalidone, indapamide) would be the best treatment option. Beta-blockers would be reserved for specific indications. If BP is not controlled with two drugs (preferably used in fixed combination in a single tablet), triple therapy would be used, the most recommended combination, if there are no contraindications, being renin angiotensin aldosterone system inhibitor + calcium antagonist + thiazide diuretic or similar. If BP is not controlled with triple therapy and good adherence to treatment and poor ambulatory control by ABPM have been confirmed, this would be resistant HTN and spironolactone is recommended as the fourth drug, and amiloride, beta-blockers or alpha-blockers as second options.

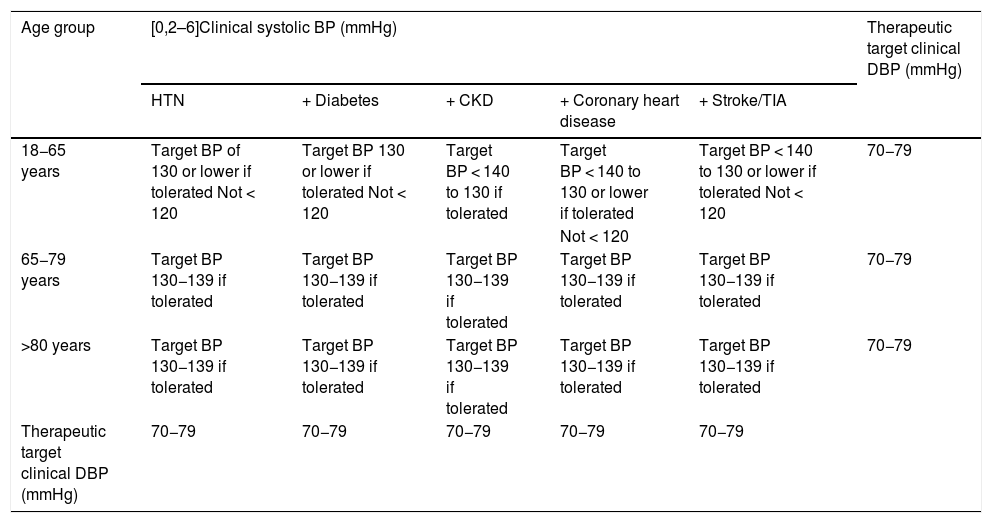

The SPRINT trial,69,179 together with meta-analyses and subsequent studies,180,181 resulted in a change in the definition and classification of HTN in the American guidelines,47 but not in the European HTN guidelines,46 where they did influence the definition of the meta-therapeutic approach. The recommended treatment is less conservative, with the therapeutic target, if well tolerated, being a reduction in systolic BP < 130/80 mmHg and a diastolic BP between 70−80 mmHg. However, in certain situations a reduction of systolic BP < 140 mmHg may be sufficient (Table 2). Antihypertensive treatment would also be indicated in subjects with white coat HTN, but with evidence of target organ damage, and therefore with elevated VR, and in subjects with normal-high BP associated with established VD.

Treatment of arterial hypertension: therapeutic target.

| Age group | [0,2–6]Clinical systolic BP (mmHg) | Therapeutic target clinical DBP (mmHg) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTN | + Diabetes | + CKD | + Coronary heart disease | + Stroke/TIA | ||

| 18−65 years | Target BP of 130 or lower if tolerated Not < 120 | Target BP 130 or lower if tolerated Not < 120 | Target BP < 140 to 130 if tolerated | Target BP < 140 to 130 or lower if tolerated | Target BP < 140 to 130 or lower if tolerated Not < 120 | 70−79 |

| Not < 120 | ||||||

| 65−79 years | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | 70−79 |

| >80 years | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | Target BP 130−139 if tolerated | 70−79 |

| Therapeutic target clinical DBP (mmHg) | 70−79 | 70−79 | 70−79 | 70−79 | 70−79 | |

HTN: arterial hypertension; BP: blood pressure; CKD: chronic kidney disease; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; TIA: transient ischaemic attack.

Taken from ESC/ESH 2018 Hypertension Guidelines.

Finally, the importance of assessing and monitoring adherence to treatment should be stressed, and the essential role of dietitians, nurses, and pharmacists in the long-term management of HTN, as well as that of family members or carers.182

Antiaggregant therapyPlatelet inhibition by aspirin reduces risk in patients with acute coronary syndrome, stroke and established cardiovascular disease.183,184 Almost 25% of US adults without VD take aspirin preventively, and this rises to 50% in those over 70 years of age, 23% of whom take it without medical advice.185 Pooled data from ten primary prevention clinical trials shows a relative reduction in cardiovascular events of 12%, corresponding in absolute terms to six fewer events per 10,000 people each year (mainly at the expense of non-fatal myocardial infarction) and an increase in the relative risk of major bleeding of 54%, corresponding in absolute terms to three more bleeds (mainly gastrointestinal) per 10,000 people each year.183 Three new trials in primary prevention have recently been published: the ARRIVE trial,186 in more than 12,000 individuals with moderate VR, with a five-year follow-up, observed no more than a doubling of the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding with no cardiovascular benefit. The ASCEND trial187 in 15,480 diabetic individuals, with a follow-up of 7.4 years, showed a 12% reduction in cardiovascular events and a 29% increase in major bleeds. The ASPREE trial188 in 19,114 individuals over 70 years of age (65 for black and Hispanic people), with a follow-up time of 4.7 years, showed a 38% increase in major bleeding and a slight increase in total mortality, with no reduction in vascular events.

A recently published benefit-harm analysis of aspirin illustrates the different scenarios that could be encountered, which may result in both net benefit and net harm.189 Faced with this uncertainty, the position of the various guidelines differs. The 2019 ACC/AHA guidelines propose considering aspirin in adults aged 40–70 years and high VR (weak recommendation) but contraindicate it in adults at high risk of bleeding or in people aged over 70 years.21 The European guidelines do not recommend aspirin for primary prevention at all.3 The ESC and EASD guidelines on diabetes, pre-diabetes and cardiovascular disease recommend considering aspirin in primary prevention in high or very high-risk diabetic patients if there is no contraindication.45

In conclusion, aspirin should not be used in primary prevention of VD because the risks of bleeding may outweigh the potential benefits, with few exceptions (high VR diabetic patients: with other VR factors or target organ involvement) and without contraindications for aspirin use, after discussing the benefits and risks with the patient and taking patient preference into account.

Psychosocial factorsThe European guidelines recommend treating psychosocial factors with multimodal behavioural interventions, psychotherapy, medication, and comprehensive care to counteract psychosocial stress, depression, and anxiety, to encourage behavioural change and improve the quality of life and prognosis of patients with VD and patients at high risk of VD.1

Adding psychological interventions to cardiac rehabilitation reduced depressive symptoms and cardiac morbidity, but did not improve anxiety, quality of life or cardiovascular mortality.190 Similarly, cognitive psychotherapy reduces psychological symptoms in patients with VD and symptoms of depression and anxiety, but not cardiovascular events. However, a recent trial has demonstrated for the first time a favourable effect of antidepressants on long-term cardiac outcomes.191

Non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF)Following the publication of four clinical trials comparing direct-acting anticoagulants (DOAC) with warfarin (vitamin K antagonist [VKA]),192-195 there is evidence of at least non-inferiority of efficacy for the composite incidence of stroke or systemic embolism. In terms of safety, DOAC are superior and are therefore recommended as the first-line drug of choice over VKA in NVAF.

New treatment strategies are recommended in patients with NVAF and ACS undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), after considering the results of the following studies:

- •

PIONEER AF-PCI: in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing coronary stenting, administration of rivaroxaban plus P2Y12 inhibitor for 12 months or very low dose rivaroxaban plus dual antiplatelet therapy for 1, 6 or 12 months was associated with lower bleeding rates than standard therapy with VKA and dual antiplatelet therapy for 1, 6 or 12 months.196

- •

RE-DUAL PCI: in NVAF patients who would require dual antiplatelet therapy for PCI, the use of dual therapy with dabigatran and clopidogrel or ticagrelor, without acetylsalicylic acid, resulted in a lower incidence of bleeding and was non-inferior to conventional triple therapy with ASA (and VKA) in preventing thrombotic events.197 Dual therapy with dabigatran was non-inferior to triple therapy with VKA in the composite incidence of thromboembolic events (myocardial infarction, stroke or systemic embolism), unplanned revascularisation and death.

- •

ENTRUST-AF: edoxaban was non-inferior for bleeding compared to VKA, with no difference in ischaemic events in patients with NVAF + PCI.198

Taken together, these studies provide clinical guidance to recommend the use of dual therapy, DOAC + clopidogrel, in NVAF patients undergoing PCI, especially in patients at high risk of bleeding.199

Coronary heart disease (CHD)In patients with CHD, secondary prevention should start at the time of diagnosis and physicians are key in coordinating this intervention, providing the tools for long-term follow-up, and ensuring continuity of care.200

A holistic approach is recommended to assess the patient's risk and plan a prevention programme according to the patient's clinical, social, and mental situation. Prevention programmes should target all patients with or at high risk of developing VD. Despite significant improvements in the management of ACS patients, secondary prevention remains a challenge and a pending issue for professionals treating vascular risk.201

Implementation of evidence-based pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions remains very poor.202-204 These interventions need to be prioritised in ACS patients to improve the long-term prognosis of the condition. It is essential to identify the barriers in each health system to address them and to ensure adequate management and support for secondary prevention.205

Heart failure (HF)HF-related biomarkers are very useful in the diagnosis and prognosis of HF. Natriuretic peptides and high-sensitivity troponin 209 are recommended in the follow-up of HF,206 as assaying them, in combination with the patient's clinical data, guides the response to treatment and prognosis. There are other biomarkers that provide information on myocardial fibrosis, endothelial dysfunction or the patient’s degree of congestion and could help in the therapeutic management of these patients in the evolution of their HF, but their value in clinical practice is yet to be determined.206,207

Cerebrovascular diseaseThe update of the European guidelines introduces the concept of silent cerebrovascular disease as a risk marker for stroke and vascular dementia and the need in these cases to maximise the control of vascular risk factors in prevention.3

The beneficial effect of dual antiplatelet therapy in secondary stroke prevention206,208-211 refers to non-cardioembolic strokes, where the optimal treatment is anticoagulation, and in subjects without large vessel disease who are susceptible to revascularisation techniques. Two studies suggest that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel may also be beneficial in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis.212,213 The benefit of increasing platelet aggregation inhibition in secondary stroke prevention, through the synergistic action of two drugs, is determined by the balance between the effect on reducing stroke recurrence and risk for bleeding. Previous studies showed no net benefit in long-term prevention with an increased bleeding risk associated with dual antiplatelet therapy.214,215 The benefit from more recent studies is that treatment should be initiated within 24 h of stroke, which reduces recurrences in the period when the risk is greatest. Thus, they show a greater effect in the first week following stroke. These studies also indicate that the benefit, which is greater in higher-risk subjects, is lost after the first 21 days of treatment due to a progressive increase in bleeding risk. It is therefore recommended that dual antiplatelet therapy with clopidogrel 75 mg/day and aspirin at a maximum dose of 100 mg/day be initiated in the first 24 h after a mild stroke or non-cardioembolic high-risk transient ischaemic attack, when carotid revascularisation is not indicated, over a period of three weeks. Thereafter, single-drug antiplatelet therapy is indicated.216 Dual antiplatelet therapy may also be beneficial in patients with symptomatic intracranial stenosis.

Optimal treatment in secondary prevention should include strict control of vascular risk factors and combining drugs such as statins. The relationship between elevated LDL-C and triglyceride levels and the risk of atherothrombotic ischaemic stroke is well established but is uncertain in strokes of other aetiologies.217,218 Atherothrombotic ischaemic stroke is equivalent in terms of VR estimation to other atherothrombotic diseases such as ischaemic heart disease. Reductions in LDL-C levels below 70 mg/dL in patients with previous ischaemic stroke are of greater benefit in preventing new vascular events, including ischaemic stroke, with a relative risk reduction of 26% with no increased risk of bleeding.219,220 Reducing LDL-C levels below 55 mg/dL is effective in preventing ischaemic heart disease and stroke in patients with previous atherosclerotic disease.147,221,222 Post-hoc analyses of the IMPROVE-IT223 and FOURIER224 trials indicate that, also in patients with previous stroke, a reduction of LDL-C levels below 55 mg/dL reduces the relative risk of recurrent stroke by 48% and 15% respectively. The greater benefit of a more intense reduction of LDL-C levels in secondary prevention of ischaemic stroke is confirmed in a meta-analysis of clinical trials combining statins with ezetimibe or PCSK9 inhibitors.223-225 Therefore, in patients with ischaemic stroke or TIA of atherothrombotic origin, treatment with statins is recommended, adding other lipid-lowering agents if necessary, to reduce LDL-C by 50% and reach the target of <55 mg/dL.225

Peripheral arterial diseasePeripheral vascular disease is a cause of physical limitation, risk of lower limb amputation and vascular events in other territories, principally cardiac and cerebral.226 The addition of the ankle/brachial index to VR scales is associated with modest improvements in discrimination and reclassification, and only appears to be of interest when classical risk factor-based models predict cardiovascular events poorly.227

Smoking cessation and physical exercise are associated with an improvement in walking perimeter without pain. In the last 20 years, these patients have received antithrombotic treatment and have been monitored for other RF at secondary prevention levels. The aim of these measures was to reduce the risk of cardiac and cerebrovascular events.

The update of the European guidelines highlights the results of two recent trials which, for the first time, demonstrate that medical treatment can reduce the risk of critical, acute ischaemia or limb amputation.3 In the COMPASS trial,228 the addition of low-dose rivaroxaban (2.5 mg twice daily) to acetylsalicylic acid (100 mg/24 h) reduced the combined incidence of cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction or stroke and amputation by 58% and the risk of requiring a revascularisation procedure by 24%. In the PEGASUS-TIMI,229 study of patients who had suffered myocardial infarction, the addition of ticagrelor to low-dose aspirin reduced the risk of adverse cardiovascular and limb events (acute ischaemia or need for revascularisation) by 35%. In both studies, the decrease in the risk of lower limb ischaemic events was at the cost of an increase in bleeding episodes, therefore the administration of these drug combinations for secondary prevention of limb ischaemic events should be considered after assessment of the patient's thrombotic and bleeding risks, and there is no clear recommendation. In the FOURIER trial, treatment with evolocumab reduced the risk of acute ischaemic events or the need for urgent revascularisation or limb amputation by 42%.230 The results of these three trials raise new expectations in the treatment of peripheral vascular disease and have identified reduction of peripheral ischaemic events and amputation as a therapeutic target of interest.

Monitoring preventive activities: compliance standardsThe European guidelines recommend monitoring the implementation processes of vascular prevention activities and their outcomes to improve the quality of care in clinical practice.1 This update stresses the need to implement measures targeting the population and specified in public reports.3 The European Society of Cardiology proposes a quality of care programme to develop and implement the accreditation of clinical centres providing primary prevention, secondary prevention, rehabilitation and sports cardiology.231

The American ACC/AHA guidelines have already updated the standardisation of quality measures for cardiac rehabilitation (CR),232 establishing the following quality indicators:

- 1

Referral of inpatients with indication for CR: percentage of hospitalised patients with indication for CR/patients referred for CR in the last 12 months.

- 2

Referral to supervised physical exercise programmes in patients with HF: percentage of hospitalised patients with a diagnosis of HF with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF)) with an indication for CR/patients with HFrEF referred for CR.

- 3

Referral of outpatients with indication for CR: percentage of outpatients who in the previous 12 months had an ACS with indication for CR/outpatients who were referred for CR.

- 4

Exercise training referral for HF (outpatient setting): percentage of outpatients who in the previous 12 months had been admitted due to HFrEF with indication for CR but were not referred for CR.

- 5

Patients referred for CR who attend the programme: percentage of patients with an indication for CR attending at least one session of the programme.

- 6

Registry of patients referred for cardiac rehabilitation: percentage of patients with an indication for CR who have attended at least one session of the CR programme.

All cardiovascular prevention or CR programmes should formally undergo regular audits to assess quality indicators and ensure best practice in prevention and CR programmes.

e-Health clinical domainse-Health-related interventions can help to implement vascular prevention activities in all individuals in different risk categories in a much broader population. Telemedicine activities are cost-effective.233 Telemedicine as an alternative or complementary to cardiac rehabilitation is associated with a reduction in recurrent cardiovascular events, LDL-C levels, and smoking.234

The use of mobile apps is steadily increasing, with several attractive elements for users: lifestyle tracking, self-monitoring for health education, and flexible and customisable options.234 However, studies find variable results in effectiveness in terms of risk factor management and self-management. The limitations of e-Health interventions are their variability and the need to determine the characteristics, components, frequency, and duration of contact that are most effective in changing lifestyles and reducing VR.

Aspects of knowledge as yet unresolvedThe many aspects of knowledge still to be resolved include3:

- •

The need for re-evaluation and recalibration of VR tables.

- •

The role of biomarkers in VR estimation.

- •

The cost-effectiveness of using genetic testing in clinical practice in VR.

- •

The usefulness of coronary CT in the stratification of VR in asymptomatic subjects.

- •

Estimation of the magnitude of the vascular problem in young subjects.

- •

The decision to initiate treatment in primary prevention in subjects >75 years.

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: Armario P, Brotons C, Elosua R, Alonso de Leciñana M, Castro A, Clarà A, et al. Comentario del CEIPV a la actualización de las Guías Europeas de Prevención Vascular en la Práctica Clínica. Clin Investig Arterioscler. 2021;33:85–107.

Simultaneous publication in the journals of the 15 scientific societies of the CEIPV in paper or electronic format online and in the Revista Española de Salud Pública (Spanish Journal of Public Health).