Central venous catheterization, performed by the anatomical landmark technique, has a mechanical complication rate between 5% and 19%. This technique has been modified and new approaches have been implemented aiming to improve patient safety. With the introduction of ultrasonography in the clinical practice, and recently in central venous catheter insertion, the rate of complications has dropped over time.

ObjectiveTo measure the clinical application of the algorithm “Successful ultrasound-guided internal jugular vein cannulation”.

MethodsA descriptive, prospective, case series study. Patients over 18 years of age were selected, and the informed consent documentation was filled out appropriately. Patients with masses, anatomical abnormalities, insertion site infections and coagulopathy (International Normalized Ratio [INR]≥2.0, platelet count ≤50.000) were excluded. Central venous cannulation was performed under ultrasound guidance in accordance with safety recommendations from the Anaesthesia Department of the Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá University Hospital (HUFSFB). Adjustment and validation of the algorithm was done according to an expert consensus in our department. A descriptive univariate analysis was conducted, and efficacy was determined on the basis of the number of attempts to achieve successful venous cannulation, and the incidence of complications.

ResultsThis series included 38 patients with a mean age of 62 years. In 97.4% of the cases, successful venous cannulation was achieved on the first attempt. Guidewire displacement was observed in one case, requiring a second attempt. The posterior jugular vein wall was punctured in two patients (5.2%), with no associated arterial vascular injury or pneumothorax.

ConclusionsThis algorithm resulted in a high rate of successful first attempts and the prevention of potential complications, improving operational standards and healthcare quality for the patients.

La canulación venosa central por técnica de reparos anatómicos presenta complicaciones mecánicas entre 5–19%, por tal motivo se han modificado e implementado técnicas buscando disminuir los riesgos para el paciente. La introducción de la ultrasonografía en la práctica clínica y más recientemente en la colocación de catéteres venosos centrales, ha disminuido la incidencia de complicaciones.

ObjetivoEvaluar la aplicación clínica del algoritmo “Adecuada inserción de catéteres venosos yugulares internos guiados por ultrasonografía”.

MetodologíaEstudio descriptivo prospectivo de serie de casos. Se seleccionaron pacientes mayores de 18 años de edad, con el consentimiento informado completamente diligenciado. Los criterios de exclusión fueron pacientes con masas, alteraciones anatómicas o infecciones en el sitio de punción, trastornos de coagulación (Índice Normalizado Internacional INR≥2,0 y conteo plaquetario ≤50.000). La canulación venosa central fue realizada con técnica ultrasonofigura considerando las recomendaciones de seguridad que se tienen en el departamento de anestesia del Hospital Universitario Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá (HUFSFB), los ajustes y validación del algoritmo guía se realizaron según el consenso de expertos en procedimientos invasivos y ultrasonografía. Se realizó análisis descriptivo univariado y la eficacia fue determinada por el número de punciones necesarias para una adecuada canulación vascular y la incidencia de complicaciones.

ResultadosLa serie de casos fue de 38 pacientes con una edad promedio de 62 años. En el 97,4% de los casos el paso fue realizado en el primer intento. En un paciente se evidenció desplazamiento inadecuado de la guía por lo que fue necesario repetir la punción. En 2 pacientes (5,2%) se presentó punción de la pared posterior del vaso sin que esto se hubiese correlacionado con presencia de lesión vascular arterial o neumotórax.

ConclusionesLa implementación del algoritmo guía, permitió una alta tasa de éxito en el primer intento y la prevención de complicaciones potenciales, mejorando los estándares operacionales, brindando una mayor calidad en el cuidado y atención de los pacientes.

Based on the technique designed by Seldinger1 and the description by English of percutaneous internal jugular vein catheterization,2 various strategies have been developed and implemented with the aim of achieving adequate endovascular positioning and confirmation, thus reducing the incidence of complications that often result in increase morbidity, even death.

The classical landmark technique, based on the presumed location of the vessels of the neck from the identification of the external anatomical structures, is considered a blind technique. Although it is widely used and is inherent to our medical practice, mechanical complication rates ranging between 5% and 19% were reported in the United States in 2003. These have been found to be related to operator experience, population group (children and elderly patients), anatomical considerations (obese patients, anatomical variants, thrombosis), comorbidities (coagulopathies, emphysema), number of attempts by operator, prior neck surgery, and a history of failed punctures.3–11

With the introduction of ultrasound in clinical practice for the placement of central venous catheters, the incidence of complications has dropped, optimizing placement time and the number of attempts. Despite increased safety and ease, this technique is not free from adverse events.3,4,10 This has led to the development of management guidelines and protocols, in an attempt at standardizing increasingly accurate procedures with the least number of associated complications.3,4,12,13

Organizations such as the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the National Institute for Clinical Excellence have recommended the use of ultrasound for the placement of central venous catheters as one of the practices designed to improve patient safety and care.14,15 Some authors have even encouraged the broad use of ultrasound, not limiting it only to the field of radiology, in order to bring significant benefits to other specialties.8,16

At the Department of Anaesthesia of the Fundación Santa Fe de Bogotá University Hospital, skill training has been optimized, strengthening the operational development of this technique. The objective of this study was to evaluate the clinical application of a guiding algorithm for vascular cannulation developed at this institution, based on the evidence that shows the best results and the lowest complications rate.

MethodsProspective descriptive case series studyThe protocol was submitted to the institutional ethics committee and the HUFSFB Anaesthesia Department for approval. The subjects were patients undergoing elective or emergency surgical procedures requiring invasive central venous pressure monitoring.

The inclusion criteria were patients over 18 years of age with informed consent appropiately filled. The exclusion criteria were patients with masses, anatomical abnormalities, puncture site infections, or coagulation disorders (INR≥2.0 and platelet count ≤50.000).

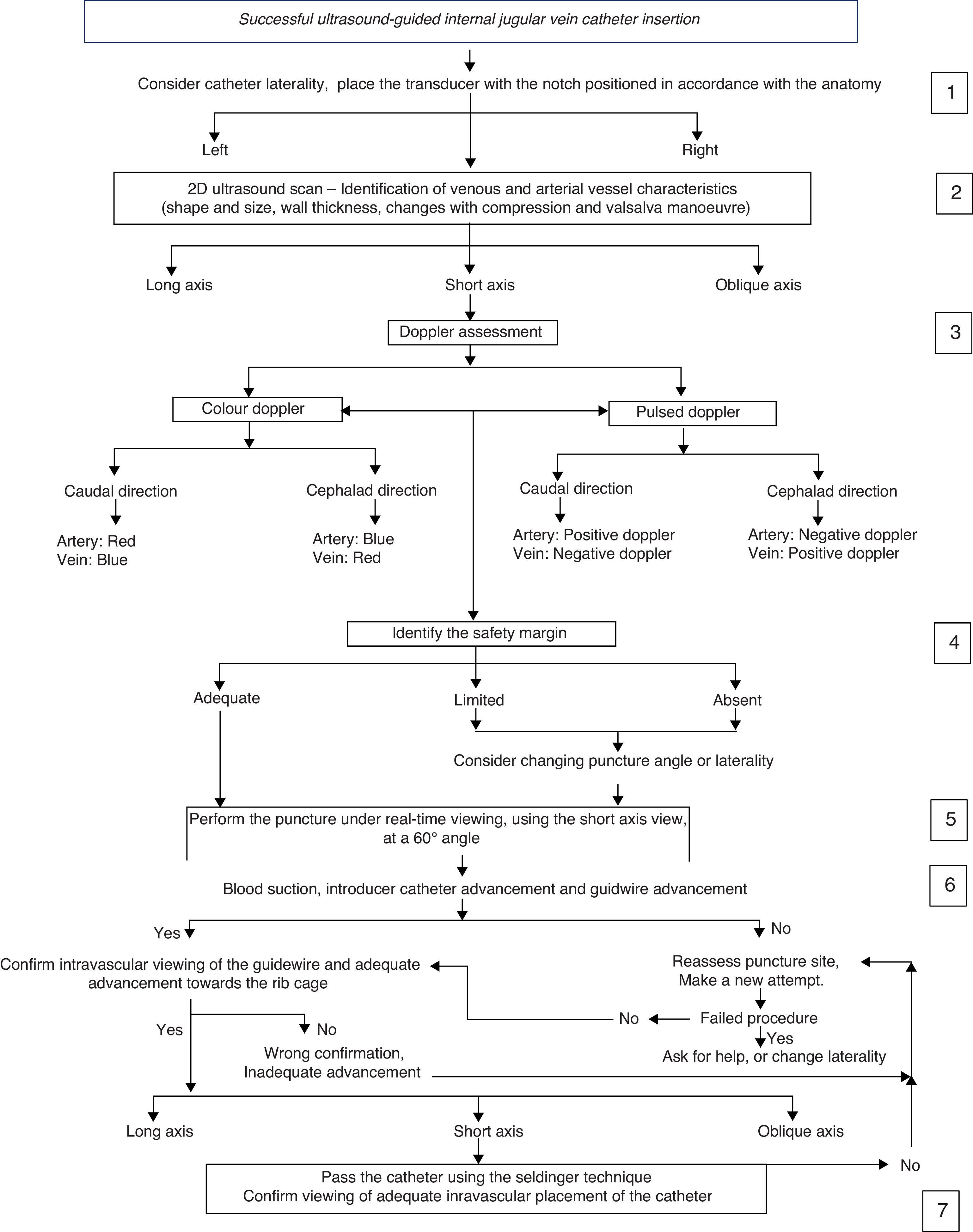

A consensus of experts in invasive procedures and ultrasound from the Department of Anaesthesia was brought together to develop an algorithm for central venous cannulation under ultrasound guidance (Fig. 1). Adjustments and validation of this procedure were based on the HUFSFB safety recommendations and management guidelines.

The data collection process was performed using a form designed for that purpose. The SPSS 19® software was used for the univariate analysis, describing proportions and central trend measurements.

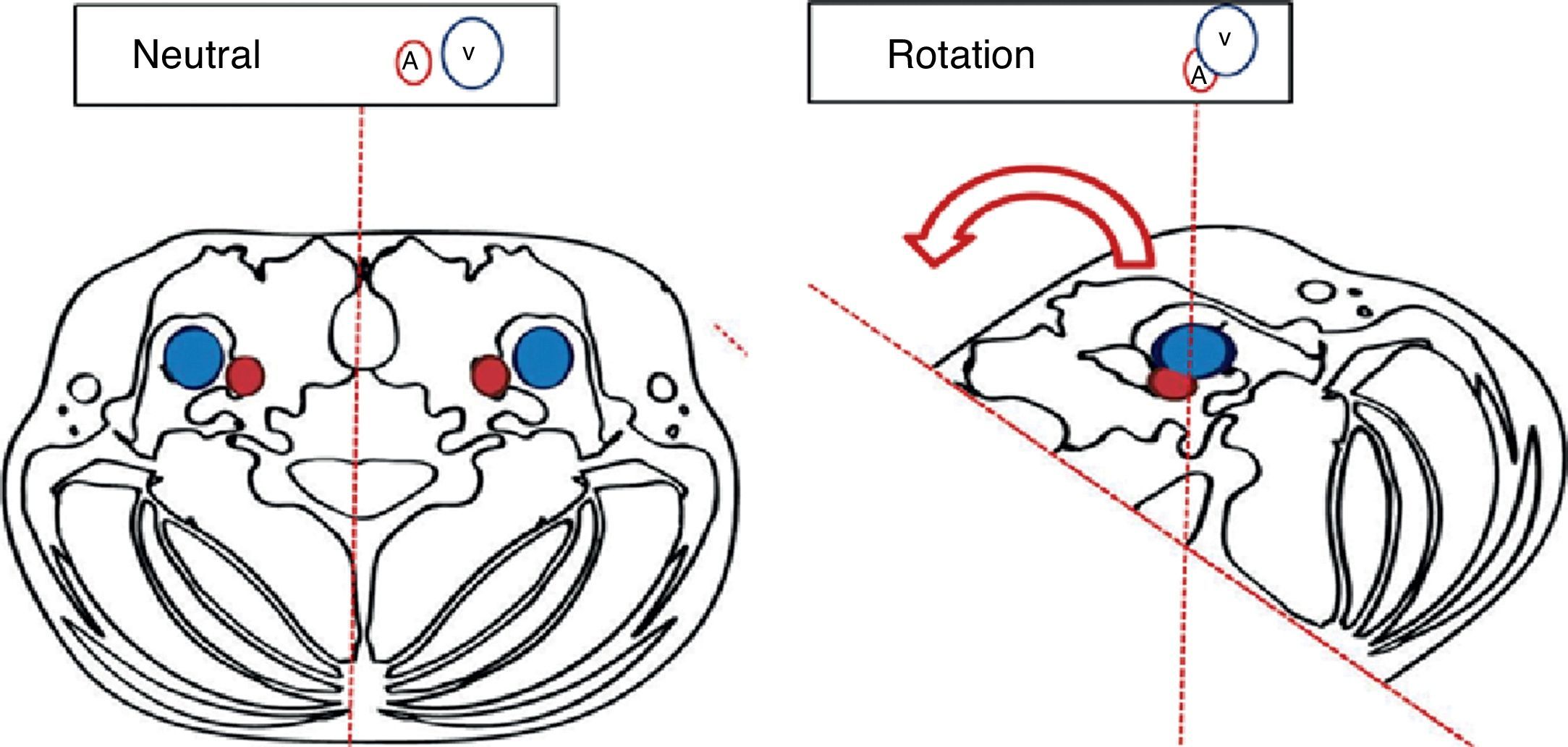

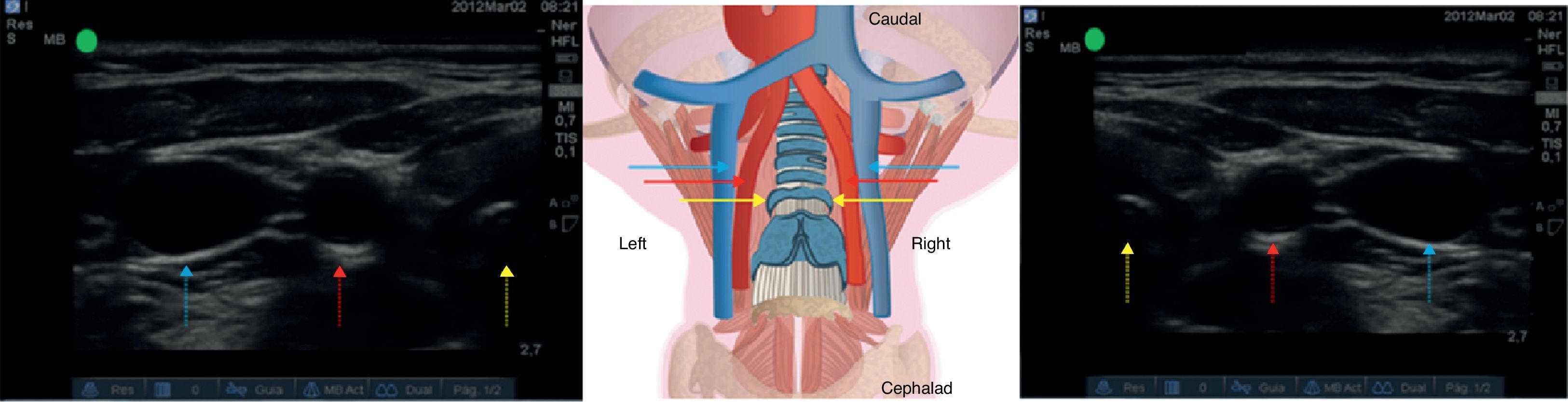

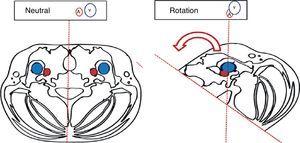

“Successful ultrasound-guided internal jugular vein catheter insertion” algorithm1. Patient positioning and catheter lateralityTrendelemburg positioning is recommended, with the head in neutral position or with the least contralateral rotation possible;17,18 the operator stands at the head of the patient with the ultrasound equipment on the ipsilateral side of the puncture area. Prior studies have shown increased vascular overlap associated with contralateral cephalad rotation.19–22 (Fig. 2) Wang et al. reported important loss of up to 72% of the safety margin with increased vascular overlap when 90° rotation is used. These data have contributed to explain arterial vascular injury during puncture.

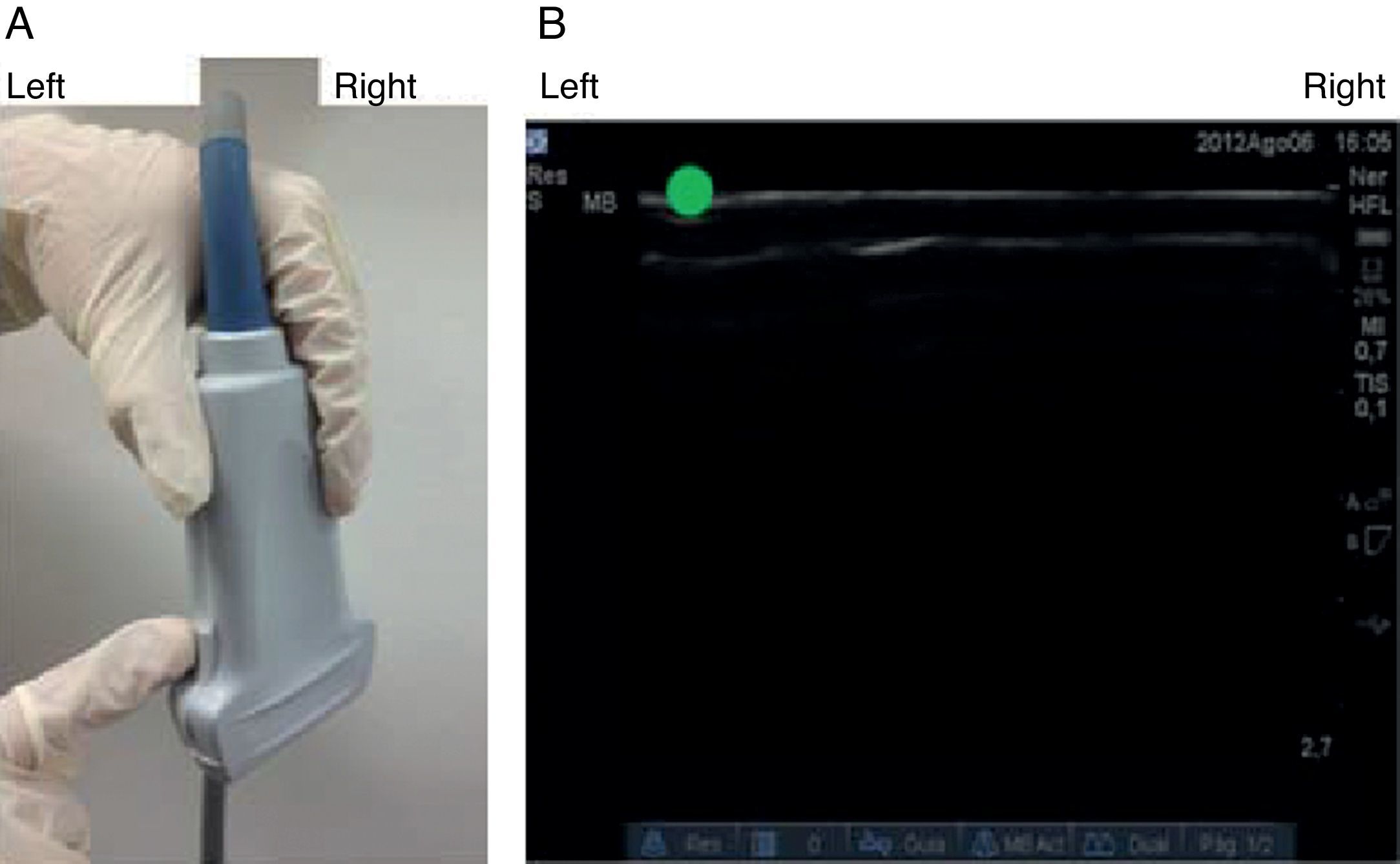

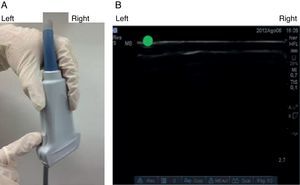

The notch in the probe helps orient laterality on the patient image and its corresponding display on the ultrasound screen. When the notch is identified (Fig. 3A), the image is found on the ultrasound screen (the green dot in our case) in order to serve as a guide to the imaged side and its schematic representation on the screen (Fig. 3B).

Correct probe placement allows identification of anatomical structures for adequate assessment of the tracheal rings and vascular structures (Fig. 4), lowering the probability of puncture error.

Ultrasound assessment of vascular structures. See the trachea (yellow arrow), followed by the common carotid artery (red arrow) and then the internal jugular vein (blue arrow). Left side. The transducer is positioned with the notch oriented laterally. Right side. The transducer is positioned with the notch oriented medially.

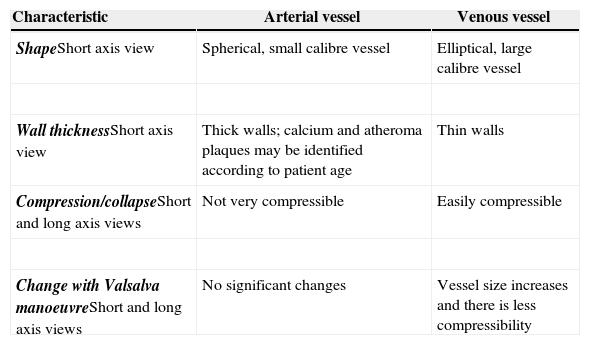

Initial vascular differentiation is done using the 2D mode to establish the distinct characteristics of the venous and arterial vessels. It is recommended to assess the short axis, the long axis and the oblique axis views (Table 1) in order to identify anatomical relationships between the structures and assess for the presence of thrombi or masses that may interfere with the cannulation.

Different characteristics of venous and arterial vessels.

| Characteristic | Arterial vessel | Venous vessel |

|---|---|---|

| ShapeShort axis view | Spherical, small calibre vessel | Elliptical, large calibre vessel |

| Wall thicknessShort axis view | Thick walls; calcium and atheroma plaques may be identified according to patient age | Thin walls |

| Compression/collapseShort and long axis views | Not very compressible | Easily compressible |

| Change with Valsalva manoeuvreShort and long axis views | No significant changes | Vessel size increases and there is less compressibility |

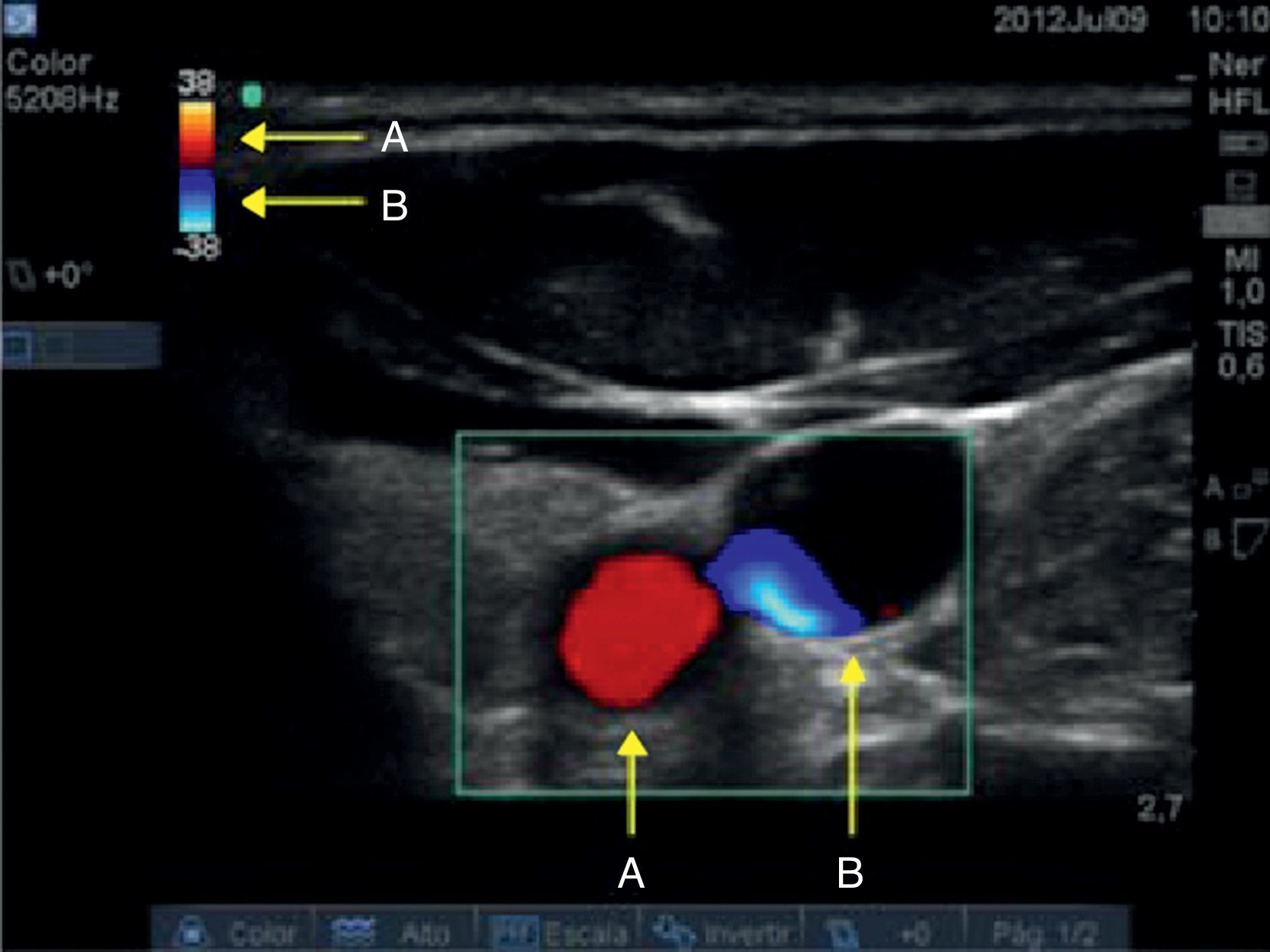

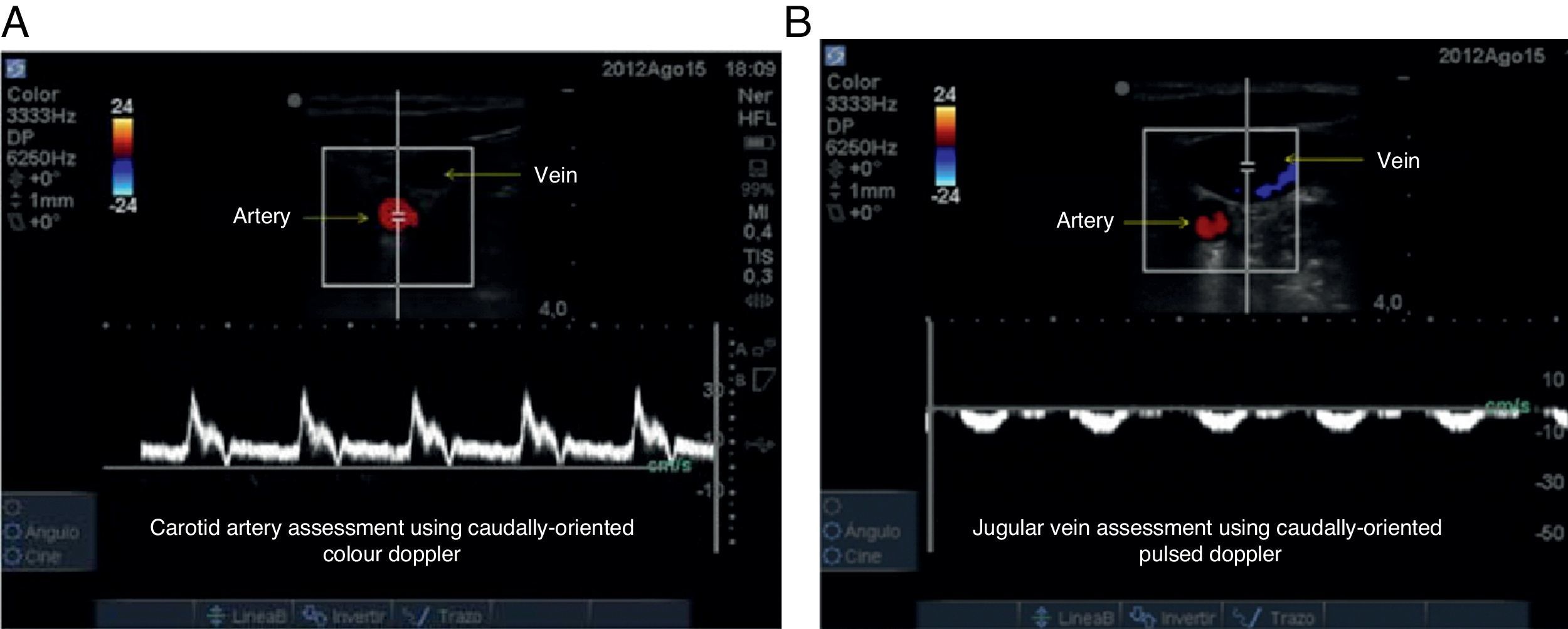

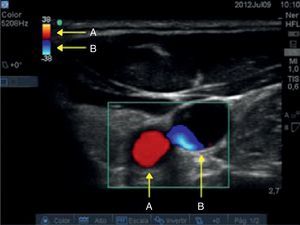

Before conducting these assessments, it is important to become familiar with the settings of the equipment. In our case, for Colour Doppler we set the colour that will identify the flow that moves towards the transducer and the flow that moves away from the transducer (Fig. 5).

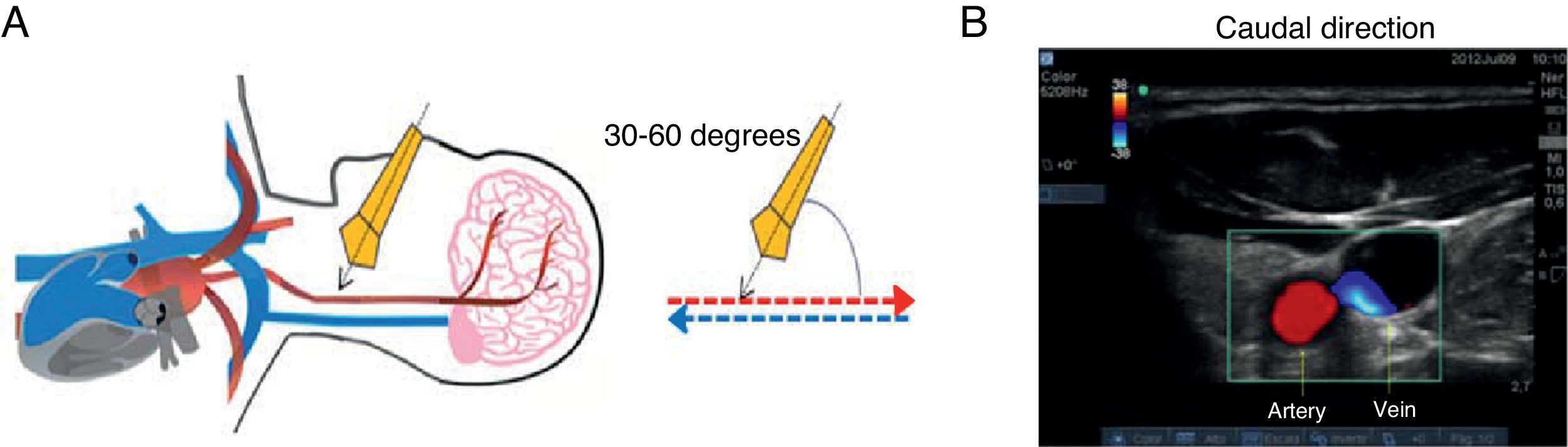

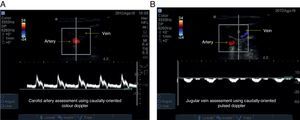

For Pulsed Doppler assessment, an incidence angle of 30–60° was considered. Angles of less than 60° must be the goal in order to avoid velocity estimation errors.23

With the determination of blood cell mass flow velocity and direction using Colour Doppler and Pulsed Doppler assessment, venous and arterial identification is significantly enhanced. The Colour Doppler assessment is performed at an angle of 30–60° in a caudal direction. On the image, the flow moving towards the transducer is flow coming from the heart and is displayed in red. The flow that appears in blue is blood moving away from the transducer, in this case flow coming from the brain and ending in the heart (Fig. 6).

Caudal-orientation Colour Doppler ultrasound assessment. (A) See the 30–60° angle of incidence between the axis of the transducer and the vessels of the neck. (B) Flow moving towards the transducer is arterial and is shown in red; flow in blue is blood going to the heart, i.e. venous flow.

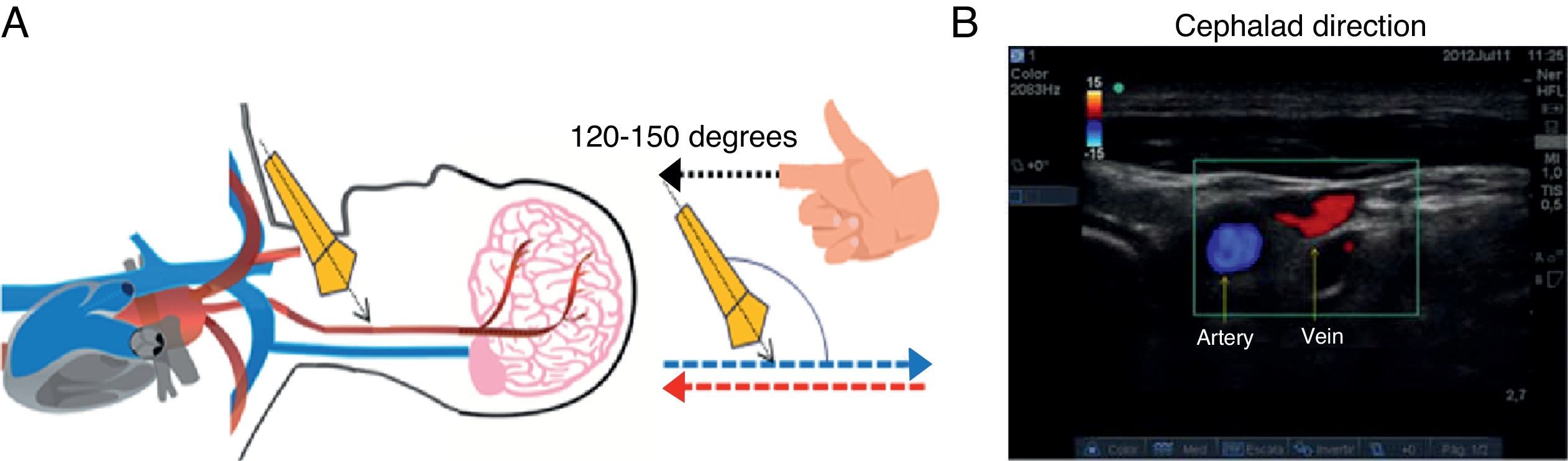

At that same point, if the assessment angle is switched to a cephalad direction (120–150°), the flow appears red, depicting blood coming from the brain, while blue flow corresponds to arterial blood coming from the heart and ending in the brain (Fig. 7).

Cephalad-oriented Colour Doppler ultrasound assessment. (A) The angle of incidence changes to 120–150° between the axis of the transducer and the vessels of the neck. (B) In this case, flow moving towards the transducer is cerebral venous return, and is shown in red; flow in blue is blood going to the brain, i.e. arterial flow.

As soon as flow direction is determined, it is important to measure velocity. When used to assess the arterial vessel in a caudal direction, Pulsed Doppler records a positive high-velocity (Fig. 8A). If the venous flow is assessed for comparison, a lower velocity negative wave is obtained (Fig. 8B). When assessment direction is changed to cephalad, the viewing direction of the waves is inverted and the negative wave represents the arterial vessel while the positive wave represents the venous vessel, and velocities are maintained.

Pulsed Doppler ultrasound assessment. (A) Arterial vessel; the blood cell mass moves towards the transducer, creating a high velocity positive spectrum (30cm/s in this case). (B) Venous vessel; a low-velocity negative spectrum is observed (10cm/s in this case), corresponding to the flow of blood cell mass away from the transducer.

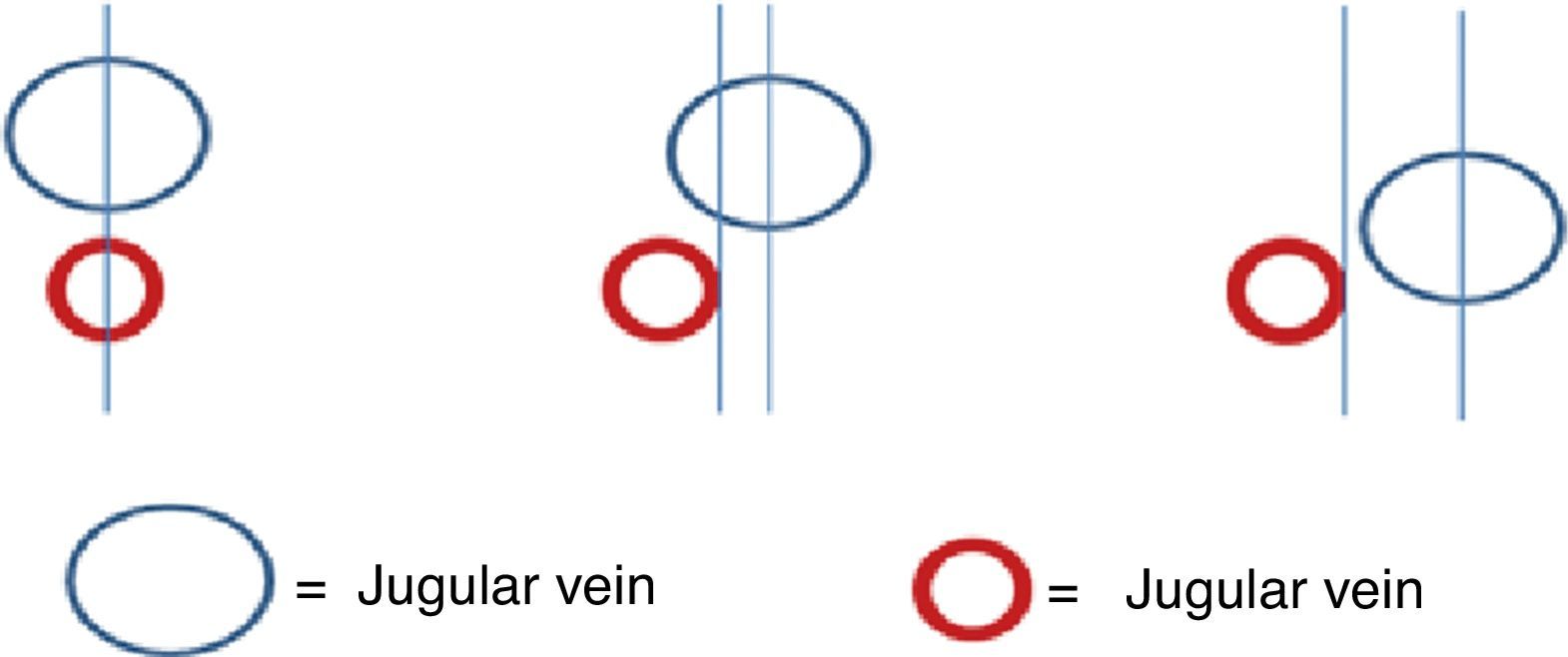

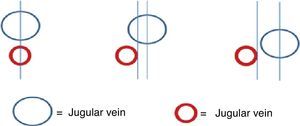

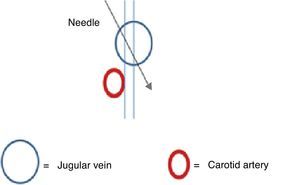

A margin of safety has been described in the short axis view, defined as the distance from the mid point of the internal jugular vein and the lateral border of the carotid artery, identifying the overlap of the jugular vein in relation to the carotid artery.3 This margin must be taken into consideration to lower the possibility of injuring the artery24 (Fig. 9).

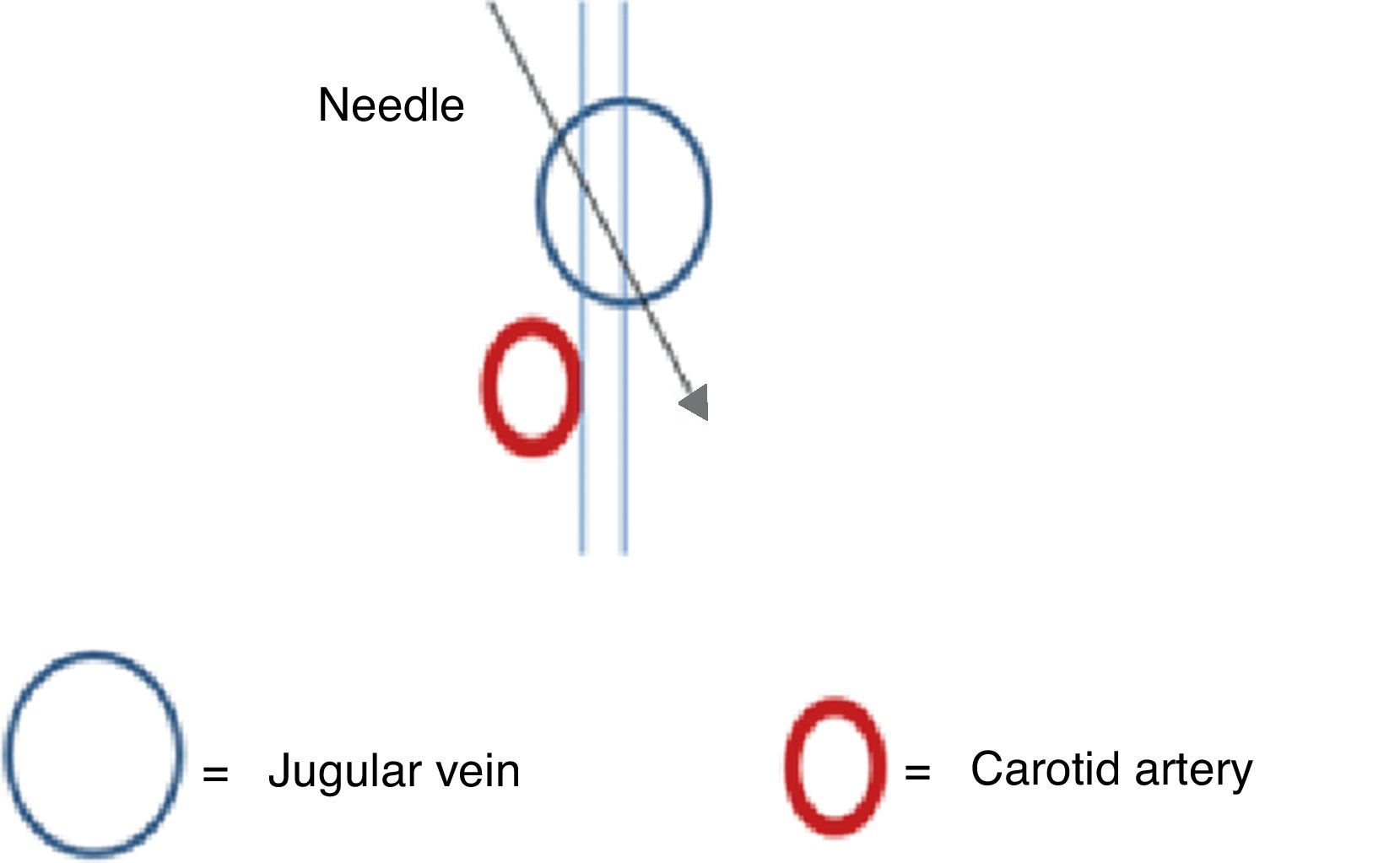

If the margin of safety is small or absent, the incidence angle must be changed during puncture (Fig. 10). If it is technically difficult to change the angle, the operator must determine the need to change catheter laterality. The internal jugular vein is a readily compressible low-pressure vessel, which means that there is a possibility of transecting the posterior wall during needle advancement.25 This manoeuvre ensures that the patient will not be subjected to multiple attempts with a potential risk of arterial vascular injury.

5. Real-time puncture visualizationWhen external compression is applied with the needle cap, the operator analyses the course and potential direction of the puncture needle. The depth at which venous return will be obtained is determined on the screen, avoiding deep punctures and potential tissue injuries or even pneumothorax.

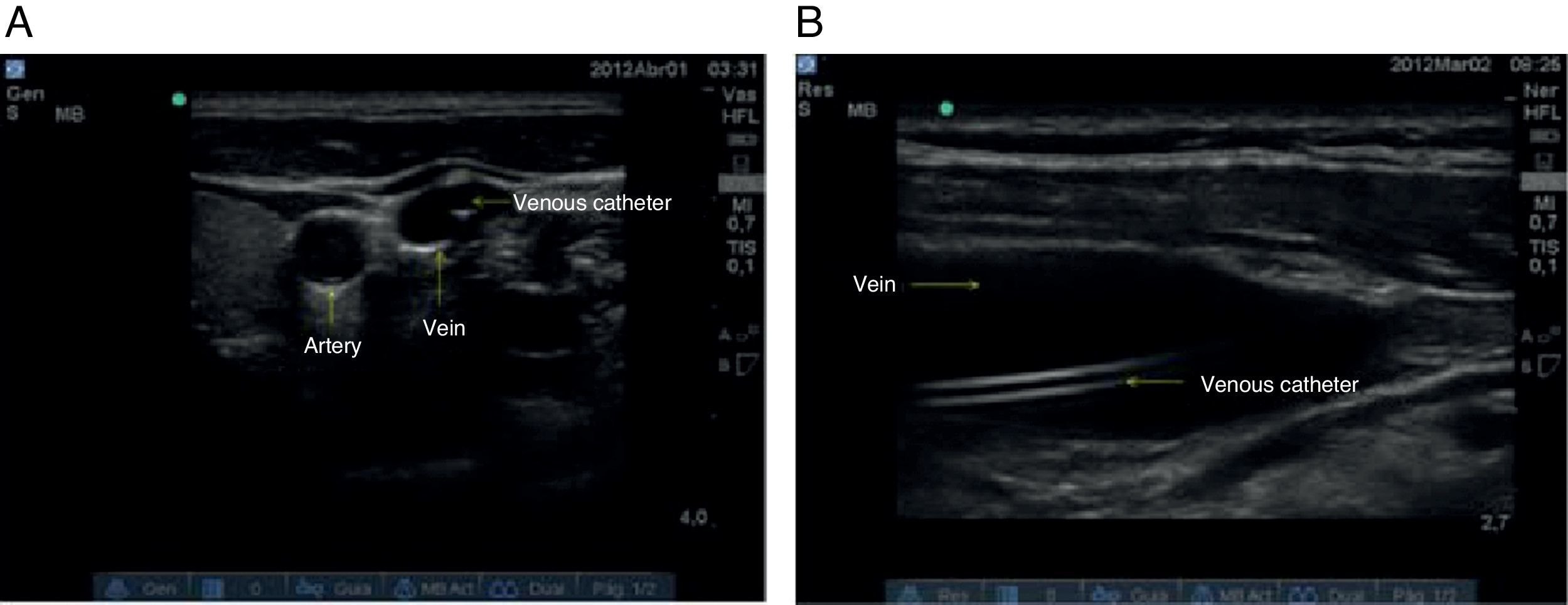

Cannulation strategies have consisted of puncturing under continuous ultrasound visualization (real-time), in the short axis view, at a 60° angle.26,27 When done in real time, it is possible to visualize the tip of the needle, direction and depth at all times, avoiding puncture of the posterior wall of the vessel or even loss of the right course; it also helps identify errors early on in order to take prompt action.28,29 Added to this, the needle is also visualized on the long-axis view, providing greater margin of safety for the patient.

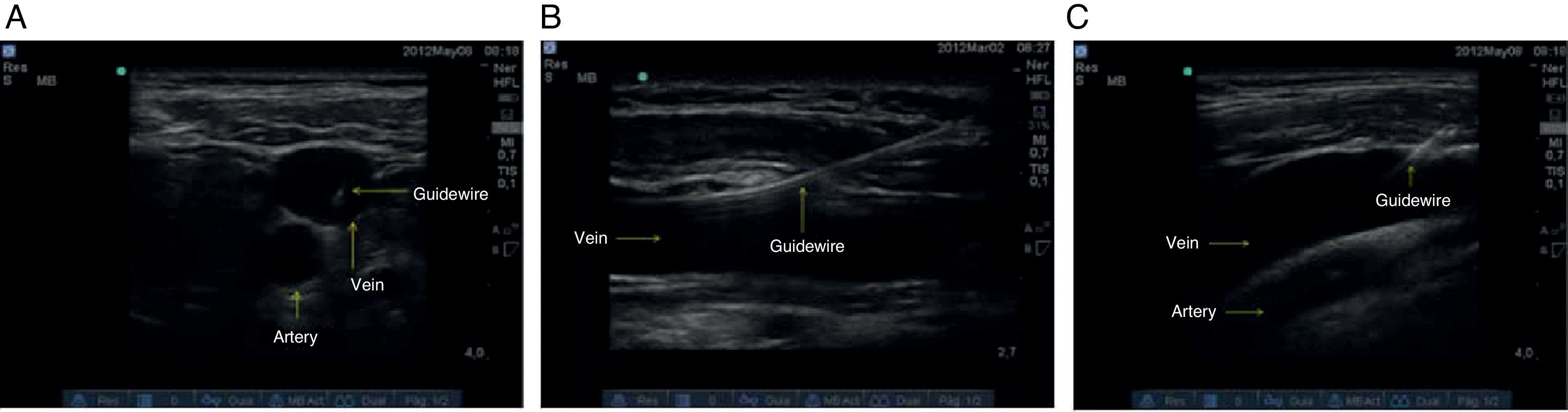

6. Catheter advancementAs soon as intravascular needle placement is observed and adequate venous return is obtained, the introducer catheter and the guidewire are allowed to slide in. The catheter-over-the-needle technique is advocated. Guidewire advancement should be smooth and unobstructed, and the maximum depth of introduction must be 15cm. In the oblique view, considering the position of the notch, the linear displacement of the guidewire towards the rib cage must be determined, ruling out the presence of intraluminal dissection, false courses or kinks that might interfere with catheter advancement.30 The assessment is complemented using the short axis and long axis views (Fig. 11).

In the event the attempt is unsuccessful, the process must be reassessed and a new attempt must be made. If the new attempt at cannulation fails, the assistance of another operator must be requested. If adequate venous return is obtained but guidewire advancement is inadequate, the possibility of changing laterality of the puncture area must be considered, because of the potential presence of venous thrombi.

It is important to avoid arrhythmias as the guidewire is advanced because induced ectopic beats have been associated with morbidity in some cases.31 There is not enough evidence regarding the efficacy of intravascular placement using continuous electrocardiogram, but there is well known the relationship between narrow complex ectopic beats and the presence of the intravascular guidewire.4,32,33

7. Catheter placement confirmationCentral venous catheter advancement is done using the Seldinger technique, followed by confirmation of adequate placement (Fig. 12). In the event of an unsuccessful attempt, the process is reassessed and step 6 is performed.

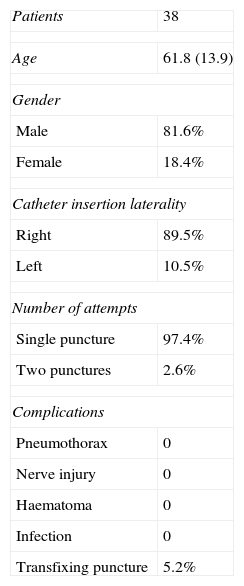

ResultsThis case series included 38 patients with a mean age of 61 years (range between 24 and 88), of whom 81.6% were males. The right side was preferred for the puncture area in 89.5% of the cases, because of the usual operator position for placing central catheters in the operating room. A single puncture attempt was required in 97.4% of the cases. In the patient who required two attempts, cephalad advancement of the guidewire was observed and it was decided to repeat the puncture (Table 2).

Characterization of assessment variables (demographic and clinical).

| Patients | 38 |

| Age | 61.8 (13.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 81.6% |

| Female | 18.4% |

| Catheter insertion laterality | |

| Right | 89.5% |

| Left | 10.5% |

| Number of attempts | |

| Single puncture | 97.4% |

| Two punctures | 2.6% |

| Complications | |

| Pneumothorax | 0 |

| Nerve injury | 0 |

| Haematoma | 0 |

| Infection | 0 |

| Transfixing puncture | 5.2% |

Note: Proportions are shown for categorical variables and means plus standard deviations (SD) are shown for continuous variables.

In 2 cases (5.2%) there was evidence of posterior vessel wall puncture unrelated with haematoma or infection. There were no complications like pneumothorax, air embolism, nerve injury, haematoma or infection. The assisted operator modality was applied in 100% of the cases, meaning tutor supervision of the resident or intern performing the procedure.

DiscussionDespite the significant advantages reported in the world literature, in 2005 Girard et al.34 studied the use of ultrasound for guiding vascular cannulation in a level III university hospital. As part of the results, they observed that only 15% of the practitioners used ultrasound guidance in more than 60% of their attempts at central vascular cannulation, showing a relatively infrequent use despite the favourable evidence.35

Excellent results published worlwide on ultrasound guided central venous cannulation, as well as the study by Raffan et al., prompted us to develop several strategies aimed at improving success and patient safety.35

Successful cannulation on the first attempt was achieved in 97.4% of the cases, similar to the 98% result found by Chittoodan in 201126 with short-axis view puncture. In this case series we chose to use and view the different approach planes, with a resulting increase in success rates and reduced complications such as carotid punctures reported with the use of the long-axis view.26

The central venous cannulation algorithm was shown to be a useful tool for performing this procedure in a systematic way, and for preventing the complications described by other authors. Despite the occurrence of posterior wall punctures in two patients (5.2%), the ability to use an adequate incidence angle reduces the possibility of puncturing the carotid artery; moreover, real time visualization prevents a too deep advancement of the needle, thus lowering the possibility of a pneumothorax.

Laterality confirmation in the displacement of the metal guidewire allows for early identification of inadequate catheter advancement or misplacement, leading to fast repositioning.

As far as the routine use of ultrasound guidance for subclavian catheter insertion is concerned, there is not enough support in the literature showing benefit or lower complications to the patient.3–5,10 Recently, Fragou et al. published a study that favoured the use of real-time ultrasonography.36 In view of the absence of conclusive studies, this procedure was not included in the algorithm. It is worth highlighting that dynamic or real-time procedures performed recently have shown better results than the use of the technique of identifying ultrasonographic landmarks or static technique.

ConclusionsThe use of the algorithm for the “Successful ultrasound-guided jugular vein catheter insertion” may be an effective way to prevent potential complications, considering that it allows for real-time adjustments, improves operational standards and provides better quality of care for patients.

ConsiderationsInteresting proposals are found in the literature regarding approaches and puncture techniques. The most convenient ones are under review in our clinical practice on the basis of the best reports, as we seek to adopt the most appropriate for our institution.36,37.

Conflict of interestWe have no conflict of interest to report.

Please cite this article as: Zuñiga WFA, Sanabria FR, de Mejía CN, Hermida E, Sánchez JA, Solórzano MC, et al. Canalización venosa yugular interna: que tanta seguridad podemos llegar a ofrecer?. Rev Colomb Anestesiol. 2015;43:76–86.