Acromegaly is a rare disease with many comorbidities that impair quality of life and limit survival. There are discrepancies in various clinical guidelines regarding diagnosis and postoperative control criteria, as well as screening and optimal management of comorbidities. This expert consensus was aimed at establishing specific recommendations for the Spanish healthcare system. The existing recommendations, the scientific evidence on which they are based, and the main controversies are reviewed. Unfortunately, the low prevalence and high clinical variability of acromegaly do not provide strong scientific evidences. To mitigate this disadvantage, a modified Delphi questionnaire, combining the best available scientific evidence with the collective judgment of experts, was used. The questionnaire, generated after a face-to-face debate, was completed by 17 Spanish endocrinologists expert in acromegaly. A high degree of consensus was reached (79.3%), as 65 of the total 82 statements raised were accepted. Some criteria for diagnosis and postoperative control were identified by this procedure. Regarding comorbidities, recommendations have been established or suggested for screening and management of oncological, cardiovascular, respiratory (sleep apnea), metabolic (dyslipidemia and diabetes), musculoskeletal, and hypopituitarism-related disorders. Consensus recommendations may facilitate and homogenize clinical care to patients with acromegaly in the Spanish health system.

La acromegalia es una enfermedad rara, con abundantes comorbilidades que deterioran la calidad de vida y limitan la supervivencia. Existen discrepancias en diversas guías clínicas respecto al diagnóstico y los criterios de control poscirugía, así como para el cribado y el manejo óptimo de las comorbilidades. El objetivo de este consenso de expertos ha sido establecer recomendaciones específicas para nuestro ámbito asistencial español. Hemos revisado las recomendaciones existentes, la evidencia científica que las sustentan y las principales controversias. Desafortunadamente, la baja prevalencia y la elevada variabilidad clínica de la acromegalia no permiten disponer de evidencias científicas sólidas. Para atenuar este inconveniente hemos utilizado un cuestionario Delphi modificado, que combina la mejor evidencia científica disponible con el juicio colectivo de expertos. Tras un debate presencial se generó el cuestionario que fue respondido por un grupo de 17 endocrinólogos españoles expertos en acromegalia. Se consiguió un alto grado de consenso (79,3%), aceptando 65 de un total de 82 aseveraciones planteadas. De esta manera, se han perfilado algunos criterios diagnósticos y de control poscirugía. Respecto a las comorbilidades, se han establecido o precisado recomendaciones para el cribado y el manejo de las enfermedades oncológica, cardiovascular, respiratoria (apnea del sueño), metabólica (dislipidemia y diabetes), osteoarticular e hipopituitarismo. Las recomendaciones consensuadas pueden facilitar y homogeneizar la asistencia clínica a los pacientes con acromegalia de nuestro sistema sanitario español.

Acromegaly is a rare disease caused in the great majority of cases (95%) by a benign monoclonal tumor proliferation of hypophyseal somatotropic cells, with growth hormone (GH) hypersecretion and secondary excess secretion of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1). It is a progressive, disfiguring disorder characterized by specific clinical manifestations, severely impaired quality of life and numerous comorbidities that may limit patient survival.1–4 The diagnosis is usually established late, and generally once the patient already has advanced disease.

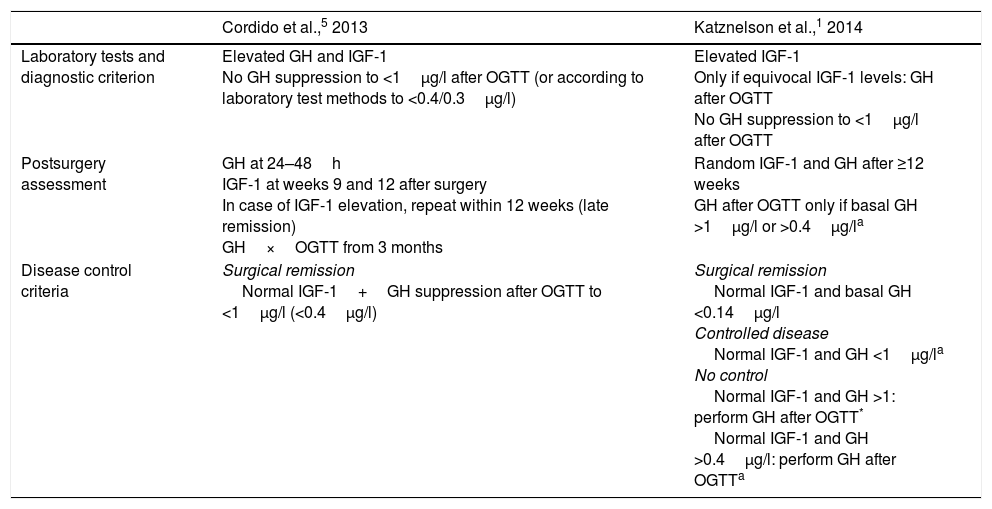

Clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and management of acromegaly and its comorbidities have been published in recent years.1,2,5 However, doubts remain regarding the procedures and criteria for diagnosis and disease control, and the recommendations are moreover confusing or imprecise (Table 1).

Diagnostic and disease control procedures and criteria.

| Cordido et al.,5 2013 | Katznelson et al.,1 2014 | |

|---|---|---|

| Laboratory tests and diagnostic criterion | Elevated GH and IGF-1 No GH suppression to <1μg/l after OGTT (or according to laboratory test methods to <0.4/0.3μg/l) | Elevated IGF-1 Only if equivocal IGF-1 levels: GH after OGTT No GH suppression to <1μg/l after OGTT |

| Postsurgery assessment | GH at 24–48h IGF-1 at weeks 9 and 12 after surgery In case of IGF-1 elevation, repeat within 12 weeks (late remission) GH×OGTT from 3 months | Random IGF-1 and GH after ≥12 weeks GH after OGTT only if basal GH >1μg/l or >0.4μg/la |

| Disease control criteria | Surgical remission Normal IGF-1+GH suppression after OGTT to <1μg/l (<0.4μg/l) | Surgical remission Normal IGF-1 and basal GH <0.14μg/l Controlled disease Normal IGF-1 and GH <1μg/la No control Normal IGF-1 and GH >1: perform GH after OGTT* Normal IGF-1 and GH >0.4μg/l: perform GH after OGTTa |

GH, growth hormone; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor-1; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

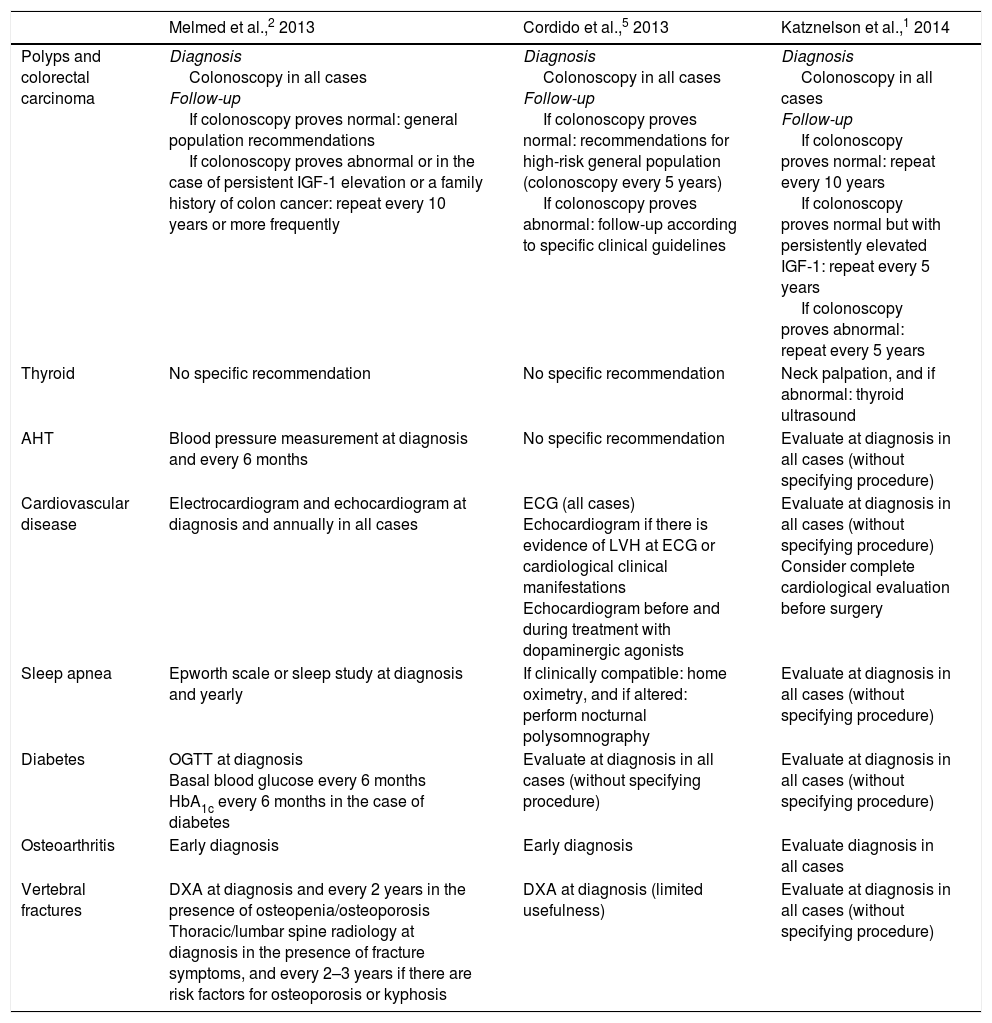

Acromegaly is associated with oncological and cardiovascular comorbidities, which constitute the main causes of the excess mortality found in these patients. Respiratory, metabolic and osteoarticular complications, as well as hypopituitarism, are also common. The diagnosis and optimum management of these comorbidities pose a challenge for endocrinologists, given the low levels of evidence available and the disparity of recommendations that are sometimes contradictory and not always suited to the reality of clinical practice (Table 2).

Recommended procedures for screening acromegaly comorbidities.

| Melmed et al.,2 2013 | Cordido et al.,5 2013 | Katznelson et al.,1 2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyps and colorectal carcinoma | Diagnosis Colonoscopy in all cases Follow-up If colonoscopy proves normal: general population recommendations If colonoscopy proves abnormal or in the case of persistent IGF-1 elevation or a family history of colon cancer: repeat every 10 years or more frequently | Diagnosis Colonoscopy in all cases Follow-up If colonoscopy proves normal: recommendations for high-risk general population (colonoscopy every 5 years) If colonoscopy proves abnormal: follow-up according to specific clinical guidelines | Diagnosis Colonoscopy in all cases Follow-up If colonoscopy proves normal: repeat every 10 years If colonoscopy proves normal but with persistently elevated IGF-1: repeat every 5 years If colonoscopy proves abnormal: repeat every 5 years |

| Thyroid | No specific recommendation | No specific recommendation | Neck palpation, and if abnormal: thyroid ultrasound |

| AHT | Blood pressure measurement at diagnosis and every 6 months | No specific recommendation | Evaluate at diagnosis in all cases (without specifying procedure) |

| Cardiovascular disease | Electrocardiogram and echocardiogram at diagnosis and annually in all cases | ECG (all cases) Echocardiogram if there is evidence of LVH at ECG or cardiological clinical manifestations Echocardiogram before and during treatment with dopaminergic agonists | Evaluate at diagnosis in all cases (without specifying procedure) Consider complete cardiological evaluation before surgery |

| Sleep apnea | Epworth scale or sleep study at diagnosis and yearly | If clinically compatible: home oximetry, and if altered: perform nocturnal polysomnography | Evaluate at diagnosis in all cases (without specifying procedure) |

| Diabetes | OGTT at diagnosis Basal blood glucose every 6 months HbA1c every 6 months in the case of diabetes | Evaluate at diagnosis in all cases (without specifying procedure) | Evaluate at diagnosis in all cases (without specifying procedure) |

| Osteoarthritis | Early diagnosis | Early diagnosis | Evaluate diagnosis in all cases |

| Vertebral fractures | DXA at diagnosis and every 2 years in the presence of osteopenia/osteoporosis Thoracic/lumbar spine radiology at diagnosis in the presence of fracture symptoms, and every 2–3 years if there are risk factors for osteoporosis or kyphosis | DXA at diagnosis (limited usefulness) | Evaluate at diagnosis in all cases (without specifying procedure) |

DXA, dual energy X-ray absorptiometry; ECG, electrocardiogram; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; AHT, arterial hypertension; LVH, left ventricular hypertrophy; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

The present expert consensus was designed with the following objectives in mind: (1) to evaluate the published scientific evidence and recommendations regarding the diagnosis and postoperative control of acromegaly, as well as the screening and management of the comorbidities of the disease; (2) to analyze the most controversial or less applicable recommendations in our clinical practice; and (3) to establish consensus-based recommendations adapted to our care setting by means of a Delphi questionnaire.

Materials and methodsA Delphi questionnaire modified according to the RAND/UCLA or appropriateness method was used,6 combining the best available scientific evidence with the collective judgment of experts, with a view to establishing statements regarding the convenience of various clinical procedures.

A scientific committee selected a panel of 17 endocrinologists with expertise in acromegaly from 9 Spanish Autonomous Communities, together with the most controversial or ambiguous topics in the field: (1) diagnostic criteria and postoperative control; (2) oncological comorbidities; (3) cardiovascular comorbidities and sleep apnea; (4) metabolic comorbidities (dyslipidemia and diabetes); and (5) osteoarticular comorbidities and hypopituitarism.

The available evidence was discussed at a joint meeting (scientific committee and expert panel). Subsequently, the scientific committee developed a questionnaire comprising 82 statements that were scored in two rounds by the expert panel. Details of the literature review, the classification of levels of evidence, and the scoring methodology and consensus criteria are detailed in Appendix A.

Results and discussionAgreement was reached on 62 statements (55 in the first round), there was disagreement on three statements (one in the first round), and no agreement was reached on 17 statements (20.7%). The results obtained are summarized in Table 3 and are detailed in Appendix A (Tables A.1–A.5).

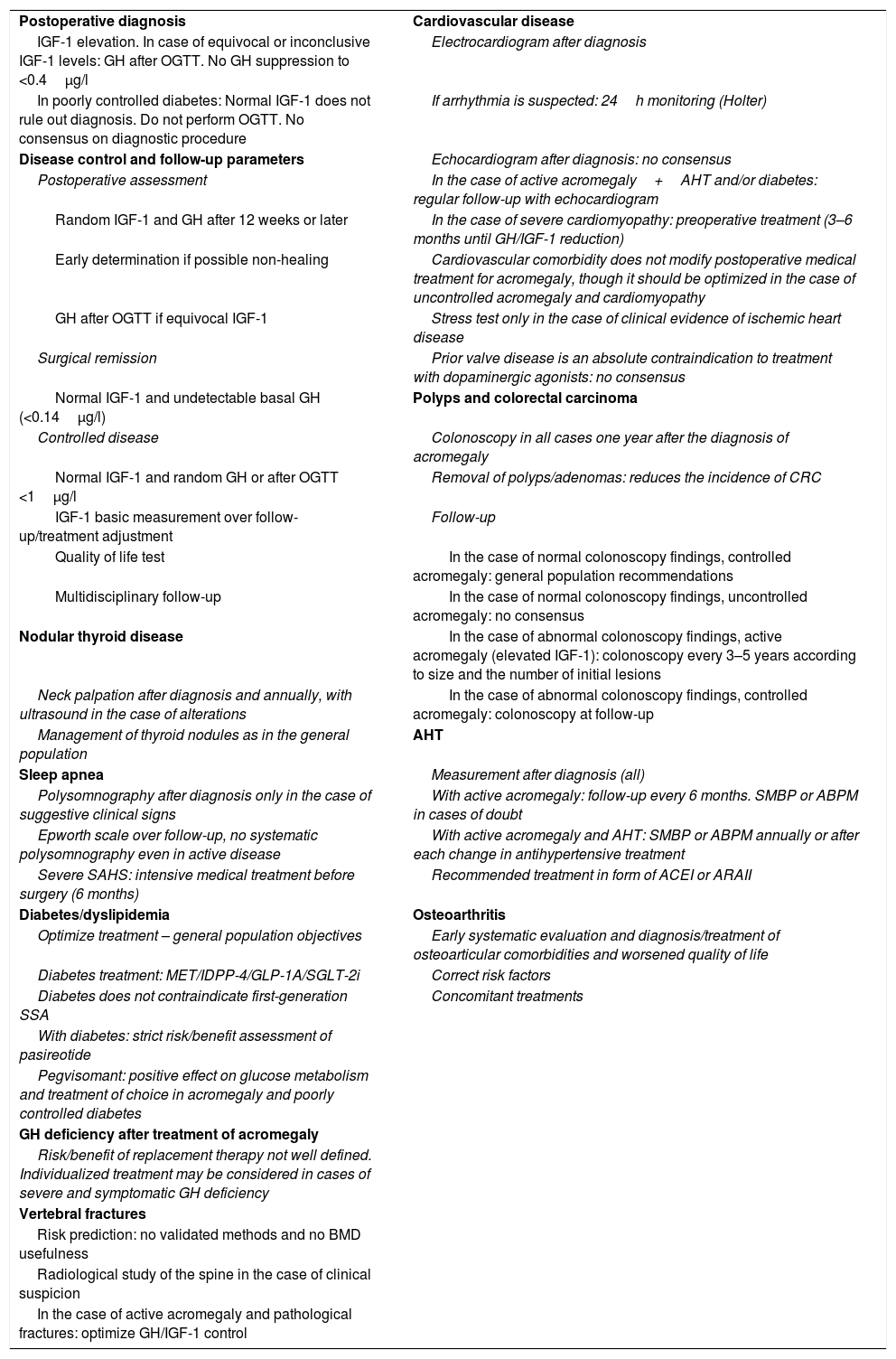

Summary of results.

| Postoperative diagnosis | Cardiovascular disease |

| IGF-1 elevation. In case of equivocal or inconclusive IGF-1 levels: GH after OGTT. No GH suppression to <0.4μg/l | Electrocardiogram after diagnosis |

| In poorly controlled diabetes: Normal IGF-1 does not rule out diagnosis. Do not perform OGTT. No consensus on diagnostic procedure | If arrhythmia is suspected: 24h monitoring (Holter) |

| Disease control and follow-up parameters | Echocardiogram after diagnosis: no consensus |

| Postoperative assessment | In the case of active acromegaly+AHT and/or diabetes: regular follow-up with echocardiogram |

| Random IGF-1 and GH after 12 weeks or later | In the case of severe cardiomyopathy: preoperative treatment (3–6 months until GH/IGF-1 reduction) |

| Early determination if possible non-healing | Cardiovascular comorbidity does not modify postoperative medical treatment for acromegaly, though it should be optimized in the case of uncontrolled acromegaly and cardiomyopathy |

| GH after OGTT if equivocal IGF-1 | Stress test only in the case of clinical evidence of ischemic heart disease |

| Surgical remission | Prior valve disease is an absolute contraindication to treatment with dopaminergic agonists: no consensus |

| Normal IGF-1 and undetectable basal GH (<0.14μg/l) | Polyps and colorectal carcinoma |

| Controlled disease | Colonoscopy in all cases one year after the diagnosis of acromegaly |

| Normal IGF-1 and random GH or after OGTT <1μg/l | Removal of polyps/adenomas: reduces the incidence of CRC |

| IGF-1 basic measurement over follow-up/treatment adjustment | Follow-up |

| Quality of life test | In the case of normal colonoscopy findings, controlled acromegaly: general population recommendations |

| Multidisciplinary follow-up | In the case of normal colonoscopy findings, uncontrolled acromegaly: no consensus |

| Nodular thyroid disease | In the case of abnormal colonoscopy findings, active acromegaly (elevated IGF-1): colonoscopy every 3–5 years according to size and the number of initial lesions |

| Neck palpation after diagnosis and annually, with ultrasound in the case of alterations | In the case of abnormal colonoscopy findings, controlled acromegaly: colonoscopy at follow-up |

| Management of thyroid nodules as in the general population | AHT |

| Sleep apnea | Measurement after diagnosis (all) |

| Polysomnography after diagnosis only in the case of suggestive clinical signs | With active acromegaly: follow-up every 6 months. SMBP or ABPM in cases of doubt |

| Epworth scale over follow-up, no systematic polysomnography even in active disease | With active acromegaly and AHT: SMBP or ABPM annually or after each change in antihypertensive treatment |

| Severe SAHS: intensive medical treatment before surgery (6 months) | Recommended treatment in form of ACEI or ARAII |

| Diabetes/dyslipidemia | Osteoarthritis |

| Optimize treatment – general population objectives | Early systematic evaluation and diagnosis/treatment of osteoarticular comorbidities and worsened quality of life |

| Diabetes treatment: MET/IDPP-4/GLP-1A/SGLT-2i | Correct risk factors |

| Diabetes does not contraindicate first-generation SSA | Concomitant treatments |

| With diabetes: strict risk/benefit assessment of pasireotide | |

| Pegvisomant: positive effect on glucose metabolism and treatment of choice in acromegaly and poorly controlled diabetes | |

| GH deficiency after treatment of acromegaly | |

| Risk/benefit of replacement therapy not well defined. Individualized treatment may be considered in cases of severe and symptomatic GH deficiency | |

| Vertebral fractures | |

| Risk prediction: no validated methods and no BMD usefulness | |

| Radiological study of the spine in the case of clinical suspicion | |

| In the case of active acromegaly and pathological fractures: optimize GH/IGF-1 control |

GLP-1A, glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs; SMBP, self-measured blood pressure; ARAII, angiotensin II receptor antagonists; SSA, somatostatin analogs; CRC, colorectal carcinoma; BMD, bone mineral density; GH, growth hormone; AHT, arterial hypertension; IDPP-4, dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors; ACEI, angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor; IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor type-1; SGLT-2i, sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitor; ABPM, ambulatory blood pressure measurement; MET, metformin; SAHS, sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Growth hormone levels (basal or random) are not useful for diagnosing acromegaly, due to their variability, pulsatility and short half-life. While the GH curve is of diagnostic interest, it is impractical in the care setting. These inconveniences are overcome by evaluating GH suppression after an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT). The diagnostic cut-off point has decreased in parallel with the improved sensitivity of the analytical methods used. The 1999 Cortina consensus7 recommended a cut-off point of 1μg/l. More recently, with the use of more sensitive biochemical methods, some authors have recommended cut-off points of 0.3–0.4μg/l for the detection of acromegaly with low secretory activity.8

The determination of IGF-1 is fundamental for the screening, diagnosis, and monitoring of acromegaly. However, some clinical conditions (poorly controlled diabetes, malnutrition, hypothyroidism, or estrogen therapy) can modify IGF-1 concentrations and make their interpretation difficult. In patients with poorly controlled diabetes, the diagnostic procedure for acromegaly has not been well defined.9

There are discrepancies in the recommended diagnostic procedures, as well as regarding postoperative evaluation between the Spanish guide5 and the international guide sponsored by the Endocrine Society1 (Table 1).

The expert panel considered the diagnostic recommendations of the international guide to be appropriate,1 though specifying that in the case of low activity acromegaly, the GH cut-off point after OGTT could be less than 1μg/l and even less than 0.4μg/l (Appendix B, Table A.1). With regard to the diagnosis in poorly controlled diabetic patients, there was agreement that the presence of normal IGF-1 levels should not rule out the diagnosis of acromegaly, and that the evaluation of GH suppression after OGTT is not adequate in this context. No consensus was reached on the usefulness of this test once diabetes control has been improved.

With regard to postoperative control, the expert panel agreed on the international recommendations,1 considering it essential that an evaluation be carried out before 12 weeks postsurgery in those cases where surgical cure is considered improbable and additional treatment is thus required.

There was agreement in defining “cure” or “remission” as the presence of normal IGF-1 adjusted for age and undetectable random GH (<0.14μg/l). “Controlled disease” in turn was defined as the presence of normal IGF-1 and random GH or GH after OGTT <1μg/l. By contrast, the expert panel did not reach a consensus on the usefulness of measuring GH in the early postoperative period.

It was agreed that the determination of IGF-1 is the primary parameter for monitoring and adjusting medical treatment after surgery.1,5 The expert panel considered it necessary to systematically assess health-related quality of life, though consensus on the influence of the results upon treatment decisions was not reached. Finally, a broad consensus was reached on the need for a multidisciplinary approach to the management of comorbidities.

Oncological comorbiditiesThe prevalence and prognosis of oncological comorbidities in acromegaly are controversial because of the heterogeneity of the data, and presumably due to the different biochemical control levels of the reported series.2,10 In poorly controlled acromegaly, the incidence of colon polyps and colorectal cancer is increased,11 though not all series report the same results.12 An increased prevalence of thyroid gland nodules and cancer has also been reported.4,13–16 A relative increase in oncological mortality and a decrease in cardiovascular mortality has recently been described.3 Although global cancer mortality is not increased in patients with acromegaly,2,12 mortality attributable to colorectal carcinoma appears to be greater than in the general population.12

The recent guides recommend screening for polyps and colorectal carcinoma via colonoscopy following a diagnosis of acromegaly.1,2,5 Other authors17 restrict this measure to patients over 40–50 years of age. During follow-up, colonoscopic explorations at variable intervals are recommended depending on each guide, and according to the findings of previous colonoscopic studies or biochemical controls of acromegaly (Table 2).

The experts agreed to indicate colonoscopy in the first year after the diagnosis of acromegaly and acknowledged the benefit of the early removal of colon polyps and adenomas upon the incidence of colorectal carcinoma (Appendix B, Table A.2). No consensus was reached regarding the avoidance of colonoscopy in younger patients (<40 years of age), with lower GH hypersecretion and a shorter duration of the disease. The general population recommendations for colorectal carcinoma screening should be followed in patients with normal first colonoscopy findings and controlled acromegaly, but no consensus was reached regarding the optimum follow-up in patients with normal first colonoscopy findings and uncontrolled acromegaly. In the event of positive first colonoscopy findings (polyps or adenomas), regular endoscopic monitoring was recommended, and was considered indicated every 3–5 years in uncontrolled acromegaly.

Only the international guide1 established recommendations for screening thyroid gland nodules and cancer (Table 2). The expert panel considered that both after diagnosis and on an annual basis thyroid palpation and ultrasound should be performed if alterations are detected. No consensus was reached regarding the indication of routine thyroid ultrasound after diagnosis. If thyroid nodules are identified, the recommendations applicable to the general population should be followed.18 No consensus was reached regarding the convenience of fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB) of all nodules measuring over 1cm in size. Lastly, it was agreed that specific screening recommendations for other oncological conditions could not be established, and that the risk of developing such conditions may be greater in diabetic patients with higher IGF-1 levels at diagnosis.19

Cardiovascular comorbidities and sleep apneaCardiovascular disorders are the most prevalent comorbidities in acromegaly and constitute one of the main causes of excess mortality (representing 39% according to the Spanish Acromegaly Registry).20 In this regard, mention should be made of arterial hypertension (AHT) (prevalence 35%), hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (80%), valvular dysfunction (75%) and cardiac rhythm disturbances (48%).21 The presence of such comorbidities at diagnosis is more common in older patients,4 and the presence of AHT at diagnosis is associated with an increased risk of myocardial infarction or stroke over follow-up.22

The recommended screening procedures vary and are poorly defined (Table 2). According to the expert panel, screening for AHT and cardiovascular disease should be performed after diagnosis and regularly over the course of follow-up (Appendix B, Table A.3). In the event of active acromegaly, follow-up should be performed every 6 months at the clinic or, in doubtful cases, on an outpatient basis, with the self-measurement of blood pressure or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. In patients with active acromegaly and AHT, the self-measurement of blood pressure or ambulatory blood pressure monitoring should be performed at least annually or after each change in antihypertensive treatment. It was agreed that the first line treatment of AHT should consist of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) or angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARAII). Following diagnosis, electrocardiography and 24-hour electrocardiographic monitoring (only in the presence or suspicion of arrhythmias) should be performed. No agreement was reached regarding routine echocardiography after diagnosis or the need for such monitoring in young patients (<40 years) without AHT. Periodic echocardiographic monitoring was considered to be indicated in active acromegaly with AHT and/or diabetes.

Preoperative intensive medical treatment (3–6 months) is indicated in the presence of severe cardiomyopathy at diagnosis. Cardiovascular comorbidities do not modify the targets or objectives regarding acromegaly control, but imply a need to optimize treatment in order to secure early hormone control. Exercise testing is only considered indicated in the case of suspected ischemic heart disease. No consensus was reached as to whether the presence of heart valve disease is an absolute contraindication to the use of dopaminergic agonists.

The prevalence of sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome, whether obstructive or central, is 60–80% in patients with acromegaly,2,23 though its prevalence is often underestimated. Respiratory disease accounts for 10% of global mortality in acromegaly patients.12 Sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome is related to age, male gender, obesity, and GH and IGF-1 levels. The guides recommend early diagnosis and treatment, though they differ in terms of the recommendations made (Table 2).

No agreement was reached regarding the routine indication of polysomnography after the diagnosis of acromegaly, though it was seen as necessary in the presence of suggestive clinical manifestations. Serial polysomnography for monitoring active acromegaly was not considered necessary. Instead, periodic evaluation based on the Epworth test was advised. In the case of severe sleep apnea–hypopnea syndrome at diagnosis, the expert panel recommended that the possibility of intensive medical treatment in the 6 months prior to pituitary gland surgery should be considered, though without this implying any change in postoperative treatment or in the hormone control objectives.

Metabolic complications (dyslipidemia and diabetes)Excess GH results in insulin resistance, the stimulation of gluconeogenesis and lipolysis, and decreased peripheral glucose uptake. Altered basal blood glucose (7–22%), glucose intolerance (6–45%) and diabetes (16–56%) are highly prevalent in acromegaly.24 In diabetic patients there is also a significant correlation between glucose and IGF-1 concentration.4 In addition, 30–40% of all patients with acromegaly present dyslipidemia, mainly in the form of hypertriglyceridemia and lowered HDL-cholesterol levels.24 These comorbidities are associated with the development of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular complications, which in turn constitute mortality determinants. Furthermore, diabetes is a predictor of patient mortality. Early and intensive treatment of metabolic comorbidities is recommended.1,5

Surgical healing reverses the alterations in glucose metabolism characterizing acromegaly.25 Long-acting release (LAR) octreotide or lanreotide (Autogel®) has a marginal effect on glucose homeostasis.26 By contrast, pasireotide gives rise to hyperglycaemia as an adverse effect in 50–60% of all patients.27,28 Pasireotide strongly suppresses insulin secretion and incretin response, with minimal suppression of glucagon secretion and no impact upon insulin sensitivity.29 Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors and glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs are the recommended antidiabetic treatment in these cases.29 Pegvisomant has a positive effect on glucose metabolism, improving blood glucose, HbA1c and glucose tolerance.30 This effect appears to be lost when the drug is used in combination with somatostatin analogs.31

The expert panel agreed on the need to optimize the treatment of diabetes and dyslipidemia, though the treatment recommendations and control objectives are those corresponding to the general population, conditioned to the existing comorbidities (Appendix B, Table A.4). The experts did not consider diabetes to be a contraindication to the use of octreotide or lanreotide. By contrast, they considered that the risk/benefit ratio of treatment with pasireotide should be carefully evaluated. In the case of pasireotide-induced diabetes, the recommended treatment is metformin with or without glucagon-like peptide-1 analogs or dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors. There was agreement that pegvisomant allows for better control of glucose metabolism than somatostatin analogs, and that it is the treatment of choice in acromegaly with poorly controlled diabetes mellitus.

Osteoarticular comorbidities and hypopituitarismExcess GH and IGF-1 levels affect osteoarticular structures, favoring joint cartilage growth, altering trabecular microarchitecture and increasing cortical density through the stimulation of periosteal ossification.2,32 There is a high prevalence of bone and joint comorbidities in acromegaly (60–75%). These disorders affect the axial or spinal joints and are associated with pain, edema, stiffness, limited mobility, disability and a significant impairment of patient quality of life. The joint changes may be reversible in the earliest stages, though once bone changes have occurred, they prove irreversible.

The structural bone changes characteristic of acromegaly imply fragility and fracture risk. In a large European series,4 at the diagnosis of acromegaly, 12.3% of the patients had osteoporosis, 4.4% had suffered hip fracture, 4.3% vertebral fracture, and 0.6% wrist fracture. Such bone fragility is associated with normal or only slightly decreased bone mineral density; alternative procedures therefore have been proposed to assess fracture risk using high-resolution peripheral quantitative computed tomography or the trabecular bone score, which evaluates bone microarchitecture.32

The guides generically recommend the early diagnosis of osteoarticular complications, and one publication2 (Table 2) recommends a radiological study of the spine as well as the assessment of bone mineral density (using dual energy X-ray absorptiometry) in all cases following diagnosis, with subsequent biannual follow-up in the event of risk factors for osteoporosis or the presence of osteopenia/osteoporosis in the initial study, as well as a radiological study in the presence of clinical signs suggestive of vertebral fracture.

The experts agreed that the diagnosis and treatment of bone and joint complications are underestimated and should be evaluated early and systematically once the diagnosis of acromegaly has been established. Arthropathy was recognized as having an impact on patient quality of life (pain, depression, etc.), and agreement was reached on the need to secure early acromegaly control, and on the usefulness of concomitant treatments (gonadal and thyroid replacement measures, physical activity, etc.) in order to limit its impact. The treatment of osteoarthritis should be that indicated in the general population, and arthropathy may remain present after the remission of acromegaly (Appendix B, Table A.5).

With regard to osteoporosis, there was agreement on the lack of usefulness of bone mineral density, on the absence of validated methods for predicting fracture risk in acromegaly, and on the potential future usefulness of the trabecular bone score. It was considered that acromegaly involves an increased risk of vertebral fractures, and that a radiological study should be carried out in the presence of suspect clinical signs (pain, height loss, kyphosis). No agreement was reached regarding the lack of indications for radiographic studies of the spine to rule out vertebral fractures in young patients with controlled disease and no osteoarticular symptoms. Risk factors for osteoporosis and fractures (calcium intake, vitamin D deficiency, altered calcium metabolism/hyperparathyroidism, hypogonadism) should be evaluated and corrected. In the case of active acromegaly and pathological fractures or osteoporosis, medical treatment should be optimized to control the disease.

Lastly, it was agreed that although the risk/benefit ratio of GH deficiency replacement therapy after the treatment of acromegaly has not been well established, it may be a management option in severe and symptomatic GH deficiency.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, medical decisions should be based on equity and efficiency, though this may be difficult to achieve in diseases characterized by a low prevalence and with limited scientific evidence. In this scenario, recommendations must be based on expert opinions, ideally adapted to the particularities of each healthcare system. This project has made it possible to establish recommendations regarding the postoperative diagnostic procedures and management of the comorbidities of acromegaly, which are the main determinants of patient quality of life and survival. These results will be useful for the clinical management of acromegaly patients in our setting.

Financial supportPfizer financed the costs of conducting this consensus (meetings, drafting, etc.), without participating in the selection of the subjects evaluated, in discussions or in consensus decisions.

AuthorshipThe contributions of J. Aller, C. Álvarez-Escolá, C. Fajardo-Montañana, Á. Gálvez-Moreno, C. Guillín-Amarelle and G. Sesmilo were equivalent, and these authors appear in alphabetical order of the first surname.

The scientific committee was composed of the authors of the article, who contributed equally to all the consensus process presented in the manuscript, as detailed in the two sections under Material and Methods (in the main document and in Appendix A). Dr. Ignacio Bernabeu acted as coordinator during all the consensus phases.

The endocrinologists of the expert panel participated in the joint meeting (together with the scientific committee) to discuss the available evidence, and subsequently answered the questionnaire in two rounds.

Conflicts of interestIB with Pfizer, Novartis and Ipsen (consultancy fees, lectures and research grant). JA with Pfizer, Novartis and Ipsen (consultancy fees, conferences, and travel to and registrations in congresses). CFM with Pfizer, Ipsen and Novartis (conference fees). GS with Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Boehringer, Sanofi, Novartis, Ipsen and Menarini (conference fees and research aids). The rest of the authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors thank the expert panel in acromegaly (named in Appendix C, Appendix B) for their key participation in this consensus; Drs. María Dolores Julián and Pablo Rivas for their help in the literature search and editing services; and Springer Healthcare for editorial support.

Betina Biagetti: H. Vall d’Hebron (Barcelona), Concepción Blanco: H. Príncipe de Asturias (Alcalá de Henares), Rosa Cámara: H. La Fe (Valencia), María Calatayud: H. 12 de Octubre (Madrid), Fernando Cordido: Complexo Hospitalario Universitario A Coruña (La Coruña), Pablo Fernández-Catalina: H. Montecelo (Pontevedra), Inmaculada Gavilán-Villarejo: H. Puerta del Mar (Cádiz), Sonia Gaztambide: H. Cruces (Bilbao), Inmaculada González-Molero: H. Carlos Haya (Málaga), Mónica Marazuela: H. La Princesa (Madrid), Miguel Paja: H. Basurto (Bilbao), Fernando Pazos: H. Valdecilla (Santander), Ana María Ramos-Levi: H. La Princesa (Madrid), Elena Torres: H. Clínico (Granada), Pablo Trincado: H. Miguel Servet (Zaragoza), Eva Venegas: H. Virgen del Rocío (Sevilla), Almudena Vicente: H. Virgen de la Salud (Toledo).

Please cite this article as: Bernabeu I, Aller J, Álvarez-Escolá C, Fajardo-Montañana C, Gálvez-Moreno Á, Guillín-Amarelle C, et al. Criterios para el diagnóstico y el control poscirugía de la acromegalia, y el cribado y el manejo de sus comorbilidades: recomendaciones de expertos. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2018;65:297–305.