To determine the experience with healthcare among patients with type 2 diabetes according to the assistance model provided in their primary care centers, and to determine factors related with their experience.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study performed in patients with type 2 diabetes with cardiovascular or renal complications. The patients were divided in two groups according to whether they had been attended in Advanced Diabetes centers (ADC) or the traditional assistance centers. Patient’s healthcare experience was assessed with the “Instrument for Evaluation of the Experience of Chronic Patients” (IEXPAC) questionnaire, with possible scores ranging from 0 (worst experience) to 10 (best experience).

ResultsA total of 451 patients (215 from ADC and 236 from traditional assistance centers) were included. The mean overall IEXPAC scores were 5.9 ± 1.7 (ADC) and 6.0 ± 1.9 (traditional assistance centers; p = 0.82). In the multivariant analyses, in ADC, the regular follow-up by the same physician (p = 0.01) and follow-up by a nurse (p = 0.01), were associated with a better patient experience, whereas receiving a higher number of medications with a worse patient experience (p = 0.04). In the traditional assistance centers, only the regular follow-up by the same physician was associated with a better experience (p = 0.02). Patients from ADC centers reported a higher score in the quality of life scale (69.1 ± 16.5 vs 64.6 ± 17.5; p = 0.008).

ConclusionsIn general, the healthcare experience of type 2 diabetic patients with their sanitary assistance can be improved. Patients from ADC centers report a higher score in the quality of life scale.

Determinar la experiencia con la atención sanitaria de pacientes con diabetes tipo 2 según el modelo asistencial ofrecido en su centro de atención primaria y determinar los factores relacionados.

MétodosEstudio transversal, realizado en pacientes con diabetes tipo 2 y complicaciones cardiovasculares o renales. Los pacientes se dividieron en 2 grupos, en función de si fueron atendidos en Centros Avanzados de Diabetes (CAD) o siguiendo el modelo asistencial tradicional. La experiencia del paciente con la atención sanitaria se determinó mediante el cuestionario IEXPAC (Instrumento de Evaluación de la Experiencia del Paciente Crónico), donde 0 representa la peor experiencia y 10 la mejor.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 451 pacientes (215 en centros con el modelo asistencial tradicional y 236 con el modelo CAD). Las puntuaciones medias del cuestionario IEXPAC fueron 5,9 ± 1,7 (modelo CAD) y 6,0 ± 1,9 (modelo asistencial tradicional; p = 0,82). En el análisis multivariante, en los centros CAD, el seguimiento realizado por mismo especialista (p = 0,01) y el seguimiento adicional realizado por enfermería (p = 0,01) se asociaron con una mejor experiencia, mientras que recibir un mayor número de medicamentos se asoció con una peor experiencia (p = 0,04). En los centros con el modelo asistencial tradicional, sólo el seguimiento realizado por el mismo especialista se asoció con una mejor experiencia (p = 0,02). Los pacientes en centros CAD presentaron mejor puntuación en calidad de vida (69,1 ± 16,5 vs 64,6 ± 17,5; p = 0,008).

ConclusionesEn general, la experiencia de los pacientes con diabetes tipo 2 con la atención sanitaria es mejorable. Los pacientes atendidos en los centros CAD presentan mejor calidad vida.

Diabetes mellitus constitutes a true global epidemic.1 In Spain, data from the Di@bet.es study estimate that the prevalence of diabetes is 14% in the adult population, and that almost 30% have some degree of carbohydrate metabolism disorder.2 However, as a result of the progressive ageing of the population, as well as current lifestyles with people being more sedentary and overweight/obese, these figures will increase in the coming years.3 Diabetes is associated with an increase in both cardiovascular morbidity and mortality, as well as a poorer quality of life.4,5 Taking into account the growing prevalence of diabetes, and the fact that diabetic patients have an increasing life expectancy, along with more comorbidities, the financial impact of this clinical condition on the health system is very high.6,7

Although in recent years there have been great advances in the treatment of diabetes,8 the fact is that the management of these patients is usually considered from the point of view of the healthcare professional. However, people with chronic diseases like diabetes have a lot to say about how health and social services work, as well as the care they receive. Understanding their experience is essential for improvement and moving towards integrated patient-centred care. In fact, improving patients' experience with healthcare has been associated with greater clinical effectiveness and safety, as well as greater adherence to treatment, which could lead to long-term clinical benefit.9,10 Consequently, a shift in the care model towards patient-centred care is necessary, whereby it is important to understand the patient's experience and thus ensure the success of this model.9,10

In order to measure the patient's experience with the health system, specific tools are needed that allow not only for it to be quantified, but also to identify possible deficiencies and aspects requiring improvement. The IEXPAC (Instrumento de Evaluación de la Experiencia del Paciente Crónico [Instrument for Assessing the Experience of Chronic Patients]) is a scale specifically designed to determine patients' experiences with the health system, and has been validated in Spain for patients with chronic diseases, including the population with diabetes.11,12

Furthermore, the objective of the Centros Avanzados de Diabetes (CADs) [Advanced Diabetes Centres], made up of multidisciplinary teams of healthcare professionals involved in the management of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in a Health District,13 is to improve the knowledge and skills of this population, as well as to facilitate attitudes towards continuous improvement. This healthcare model focuses on three aspects of work: improving communication and integration between healthcare levels, promoting the use of specific tools and methodologies that help healthcare professionals to make clinical decisions, and promoting patient empowerment through the training of healthcare professionals in diabetes management and diabetes education, with a special focus on nursing and primary care. There are currently 69 Advanced Diabetes Centres (CADs) in Spain. However, we are not aware of any studies that have assessed the impact of CADs on patients' experience with the healthcare received.

The objectives of this study were to understand the experience of patients with type 2 diabetes with the healthcare received according to the care model and to explore possible relationships with the patient profile, the complexity of follow-up and adherence to treatment, according to the healthcare model.

Materials and methodsThe design and methodology of the study have been extensively explained in previous publications.12 Briefly, it is a cross-sectional study where four profiles of chronic patients (patients with chronic rheumatic disease, inflammatory bowel disease, human immunodeficiency virus and type 2 diabetes mellitus with cardiovascular or renal complications) answered different questionnaires in order to respond to the study objective. This study analysis refers to the cohort of patients with type 2 diabetes, over 18 years of age, with cardiovascular or renal complications, preferably followed up in at least two different consultations (either in Primary Care or in a consultation + social services assistance), and who in the doctor's opinion had sufficient skills to respond to the study questionnaires, either by themselves or with the help of a family member. In the case of patients with type 2 diabetes, 48 Primary Care physicians consecutively included the first 13 patients who met the inclusion criteria and agreed to participate in the study, from seven different Autonomous Communities (Andalusia, Asturias, Catalonia, Valencian Community, Canary Islands, Madrid and the Basque Country) between May and September 2017. In total, 23 centres with the CAD healthcare model and 25 centres with the traditional healthcare model participated. The patients answered the questionnaire questions voluntarily and anonymously from home, without the intervention or supervision of healthcare personnel, returning the completed questionnaire in a pre-paid envelope. The estimated average time taken to answer the questionnaire was 15−20 min. The study was evaluated and approved by the hospital universitario Gregorio Marañón [Gregorio Marañón University Hospital] ethics committee of Madrid. This project was reviewed and endorsed by the Federación Española de Diabetes [Spanish Diabetes Federation], as well as other patient associations.

The questionnaire included questions about the demographic characteristics of the patient (age, gender, educational level, employment status, whether he/she belongs to a patient association, search for information about his/her disease), complexity of the healthcare received (number of doctors and specialties working with the patient, nursing follow-up, social services, visits to the emergency department in the last year, hospitalisations in the last three years, if they receive help from third parties), as well as information on the treatments the patient was taking (number of different medications, injectable treatments). The Barthel index was used to estimate the degree of dependence of the patient, which ranges from 0 (total dependence) to 100 (total independence).14

Additionally, the patients completed a questionnaire on experience with healthcare (IEXPAC). IEXPAC is a validated, self-administered, 12-item, multiple-choice questionnaire. Items 1–11 describe the patient's experience in the last six months and this is made up of three domains: domain 1, which refers to productive interactions, that is, interactions between the patient and healthcare professionals (items 1, 2, 5 and 9); domain 2, which refers to the new model of the patient's relationship/interaction with the healthcare system, such as the Internet or other patients (items 3, 7 and 11); and domain 3, which refers to the patient's self-care through interventions measured by healthcare professionals (items 4, 6, 8 and 10). Item 12 refers to hospitalisation in the last three years (continuity of care) and is reported separately. To answer the questions, a five-point Likert scale was used: always (10 points), almost always (7.5 points), sometimes (5 points), almost never (2.5 points) or never (0 points). The overall score was calculated by taking the average of items 1–11 and was scored from 0 (worst experience) to 10 (best experience).11,12

Additionally, beliefs about medications were evaluated with the Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire (BMQ)15 and quality of life, using a visual analogue scale that ranged from 0 (worst state of health) to 100 (best state of health).16

In all cases, the values obtained for the patients treated according to the CAD model were compared with those reported according to the traditional healthcare model.

Statistical analysisQuantitative variables were described by the mean and standard deviation, and qualitative variables by absolute and relative values (percentages). For the comparison of qualitative variables, the Chi squared test or Fisher's exact test were used, and for quantitative variables the Student's t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA), depending on the case. In order to determine which variables could influence the overall score of the IEXPAC questionnaire, as well as each of its components, multiple linear regression models were developed.

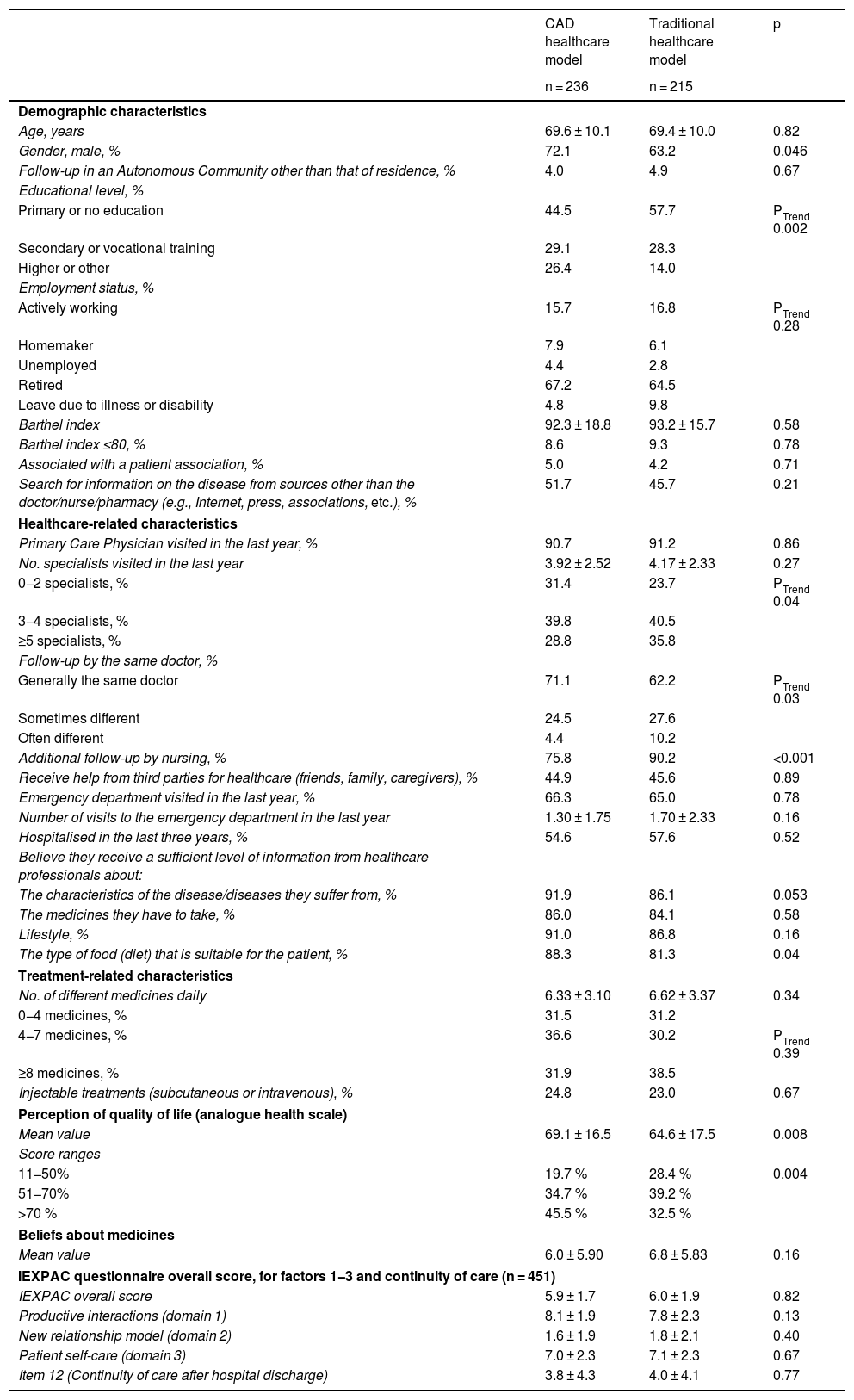

ResultsIn total, the questionnaires were distributed to 624 patients, 325 in centres with the traditional healthcare model and 299 in centres with the CAD model. Four hundred and fifty-one (451) patients responded, 215 from centres with the traditional healthcare model and 236 from centres with the CAD model (response rate 72.3%). The clinical characteristics of the patients, as well as healthcare-related characteristics are shown in Table 1. The patients were elderly (mean: 69 ± 10 years), the majority were men (68%), with low educational level (only 20% had higher education), on multiple medications (mean of 6 ± 3 different medications per day) and low participation in patient associations (<5%). Regarding the healthcare-related characteristics, there was a high rate of visits to Primary Care physicians and other specialists (approximately 40% were seen in the last year by 3−4 specialists), with a high demand for emergency departments (64% had visited an emergency department in the last year) and approximately half of the patients had been hospitalised in the last three years (56%). In most patients, follow-up was performed by the same doctor (67%) and there was a high level of additional follow-up by nurses (83%). More than 85% of the subjects reported receiving sufficient information from their healthcare professionals in general. Regarding the differences between care models, the patients treated according to the CAD model had a higher level of education (p = 0.002) and were more frequently treated by the same doctor (71.1% vs 62.2%; p = 0.03), but they had less follow-up by nursing (75.8% vs 90.2%; p < 0.001). They considered themselves to have received a higher level of information from healthcare professionals in general (including information about their disease, medications and lifestyle) and significantly more information regarding diet (88.3% vs 81.3%; p = 0.04).

Demographic characteristics, characteristics related to the healthcare and treatment of the patients who responded to the questionnaire. Perception of quality of life (analogue health scale) and beliefs about medicines (BMQ questionnaire) by care model. IEXPAC questionnaire overall score, for factors 1-3 and continuity of care by care model (n = 451).

| CAD healthcare model | Traditional healthcare model | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 236 | n = 215 | ||

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age, years | 69.6 ± 10.1 | 69.4 ± 10.0 | 0.82 |

| Gender, male, % | 72.1 | 63.2 | 0.046 |

| Follow-up in an Autonomous Community other than that of residence, % | 4.0 | 4.9 | 0.67 |

| Educational level, % | |||

| Primary or no education | 44.5 | 57.7 | PTrend 0.002 |

| Secondary or vocational training | 29.1 | 28.3 | |

| Higher or other | 26.4 | 14.0 | |

| Employment status, % | |||

| Actively working | 15.7 | 16.8 | PTrend 0.28 |

| Homemaker | 7.9 | 6.1 | |

| Unemployed | 4.4 | 2.8 | |

| Retired | 67.2 | 64.5 | |

| Leave due to illness or disability | 4.8 | 9.8 | |

| Barthel index | 92.3 ± 18.8 | 93.2 ± 15.7 | 0.58 |

| Barthel index ≤80, % | 8.6 | 9.3 | 0.78 |

| Associated with a patient association, % | 5.0 | 4.2 | 0.71 |

| Search for information on the disease from sources other than the doctor/nurse/pharmacy (e.g., Internet, press, associations, etc.), % | 51.7 | 45.7 | 0.21 |

| Healthcare-related characteristics | |||

| Primary Care Physician visited in the last year, % | 90.7 | 91.2 | 0.86 |

| No. specialists visited in the last year | 3.92 ± 2.52 | 4.17 ± 2.33 | 0.27 |

| 0−2 specialists, % | 31.4 | 23.7 | PTrend 0.04 |

| 3−4 specialists, % | 39.8 | 40.5 | |

| ≥5 specialists, % | 28.8 | 35.8 | |

| Follow-up by the same doctor, % | |||

| Generally the same doctor | 71.1 | 62.2 | PTrend 0.03 |

| Sometimes different | 24.5 | 27.6 | |

| Often different | 4.4 | 10.2 | |

| Additional follow-up by nursing, % | 75.8 | 90.2 | <0.001 |

| Receive help from third parties for healthcare (friends, family, caregivers), % | 44.9 | 45.6 | 0.89 |

| Emergency department visited in the last year, % | 66.3 | 65.0 | 0.78 |

| Number of visits to the emergency department in the last year | 1.30 ± 1.75 | 1.70 ± 2.33 | 0.16 |

| Hospitalised in the last three years, % | 54.6 | 57.6 | 0.52 |

| Believe they receive a sufficient level of information from healthcare professionals about: | |||

| The characteristics of the disease/diseases they suffer from, % | 91.9 | 86.1 | 0.053 |

| The medicines they have to take, % | 86.0 | 84.1 | 0.58 |

| Lifestyle, % | 91.0 | 86.8 | 0.16 |

| The type of food (diet) that is suitable for the patient, % | 88.3 | 81.3 | 0.04 |

| Treatment-related characteristics | |||

| No. of different medicines daily | 6.33 ± 3.10 | 6.62 ± 3.37 | 0.34 |

| 0−4 medicines, % | 31.5 | 31.2 | |

| 4−7 medicines, % | 36.6 | 30.2 | PTrend 0.39 |

| ≥8 medicines, % | 31.9 | 38.5 | |

| Injectable treatments (subcutaneous or intravenous), % | 24.8 | 23.0 | 0.67 |

| Perception of quality of life (analogue health scale) | |||

| Mean value | 69.1 ± 16.5 | 64.6 ± 17.5 | 0.008 |

| Score ranges | |||

| 11−50% | 19.7 % | 28.4 % | 0.004 |

| 51−70% | 34.7 % | 39.2 % | |

| >70 % | 45.5 % | 32.5 % | |

| Beliefs about medicines | |||

| Mean value | 6.0 ± 5.90 | 6.8 ± 5.83 | 0.16 |

| IEXPAC questionnaire overall score, for factors 1−3 and continuity of care (n = 451) | |||

| IEXPAC overall score | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.9 | 0.82 |

| Productive interactions (domain 1) | 8.1 ± 1.9 | 7.8 ± 2.3 | 0.13 |

| New relationship model (domain 2) | 1.6 ± 1.9 | 1.8 ± 2.1 | 0.40 |

| Patient self-care (domain 3) | 7.0 ± 2.3 | 7.1 ± 2.3 | 0.67 |

| Item 12 (Continuity of care after hospital discharge) | 3.8 ± 4.3 | 4.0 ± 4.1 | 0.77 |

BMQ: Beliefs About Medicines Questionnaire; CAD: Advanced Diabetes Centre.

Table 1 also summarises the data related to quality of life, adherence to treatment and beliefs about medication. In total, 45.5% of CAD patients reported a "good" to "very good" perception of quality of life (>70% score on the visual analogue scale), compared to 32.5% in patients treated under the traditional healthcare model (p = 0.004), with higher mean values on the self-reported visual analogue scale (69.1 vs 64.6; p = 0.008). Treatment adherence was high in just over 40% of the patients, with no differences between the two groups, and no significant differences were found in terms of beliefs about medication.

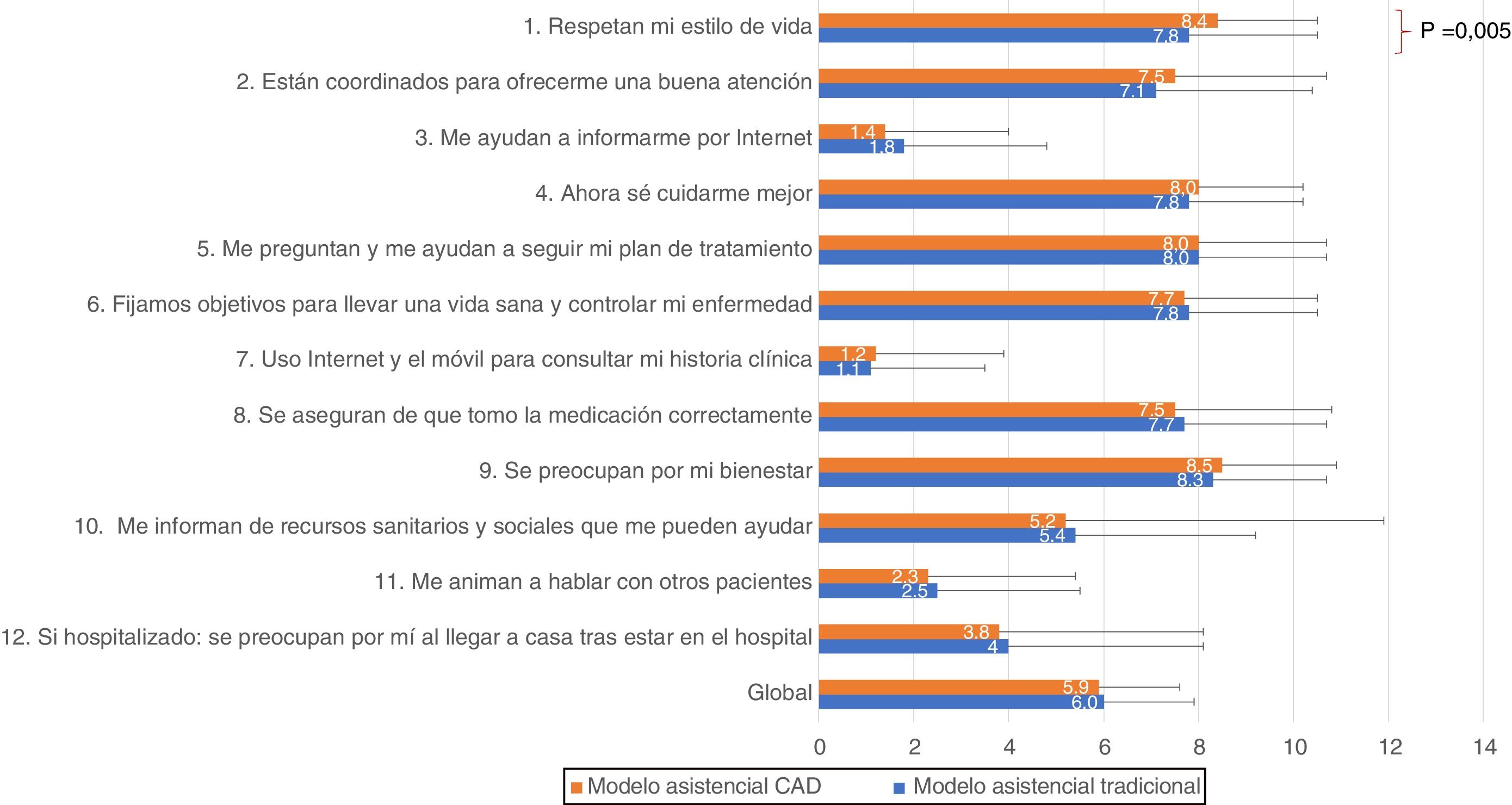

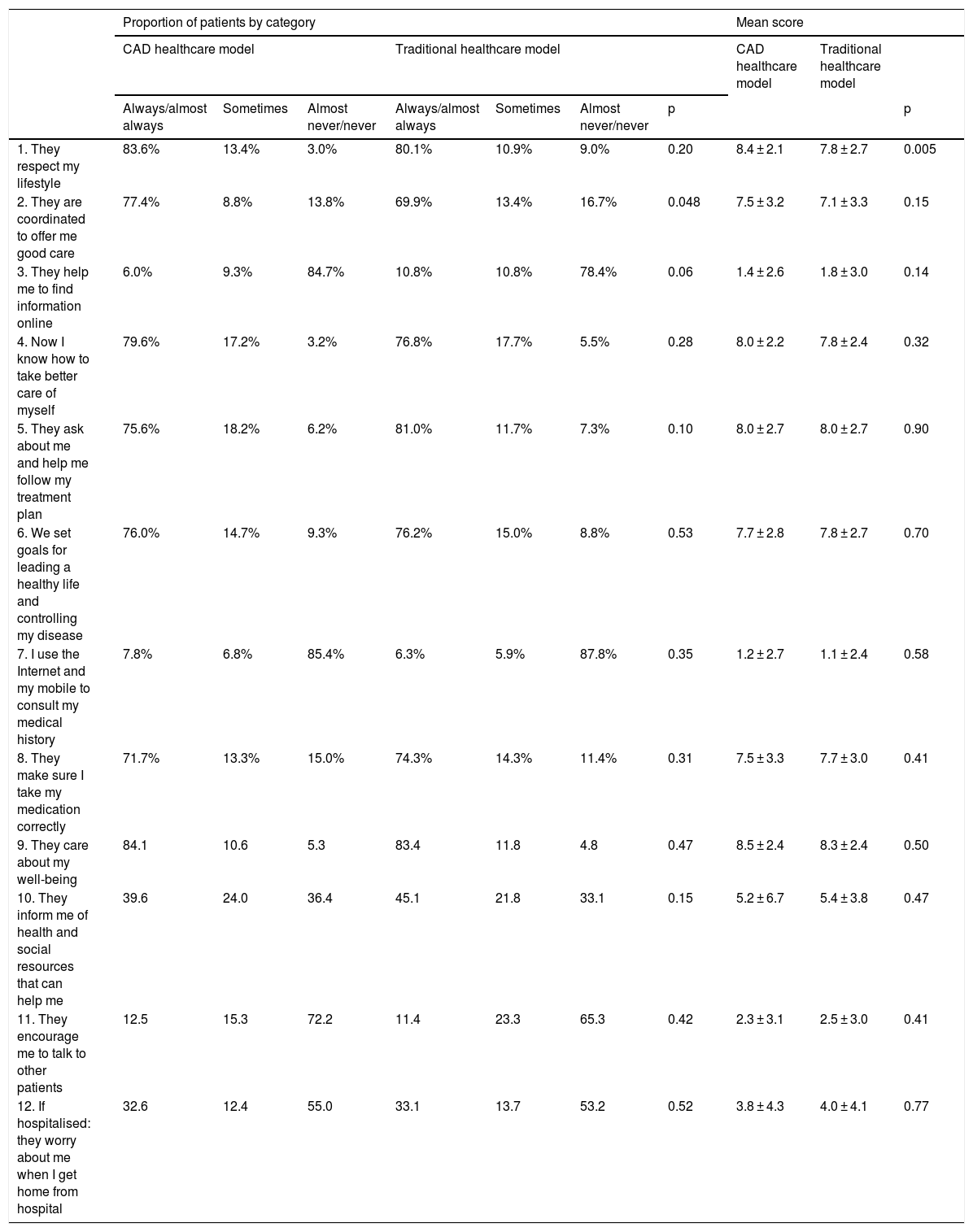

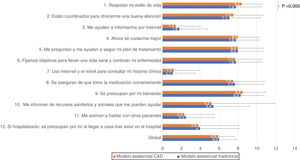

The overall IEXPAC scale score was 5.9 ± 1.7 in the CAD group and 6.0 ± 1.9 in the group of patients treated under the traditional healthcare model, with no significant differences (p = 0.82). No significant differences were found between the two groups in the scores for domains 1−3 or in the continuity of care (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Regarding the scores according to the different items (Table 2 and Fig. 1), most of the patients answered "always/almost always" to those variables related to productive interactions (domain 1, items 1, 2, 5 and 9), with the percentages for items 1 and 2 being somewhat higher in the CAD group. In contrast, in the variables related to the new relationship model (domain 2, items 3, 7 and 11), most of the patients answered "never/almost never", regardless of the care model. With regard to the variables related to self-care (domain 3, items 4, 6, 8 and 10), except for the item related to receiving information about health and social resources, most of the patients answered always/almost always in both groups. Both in the group of CAD patients and among the patients treated under the traditional care model, just over 30% of the patients who had been hospitalised in the last three years had received a follow-up call or a visit after hospital discharge.

IEXPAC questionnaire score, by item according to the care model.

| Proportion of patients by category | Mean score | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAD healthcare model | Traditional healthcare model | CAD healthcare model | Traditional healthcare model | |||||||

| Always/almost always | Sometimes | Almost never/never | Always/almost always | Sometimes | Almost never/never | p | p | |||

| 1. They respect my lifestyle | 83.6% | 13.4% | 3.0% | 80.1% | 10.9% | 9.0% | 0.20 | 8.4 ± 2.1 | 7.8 ± 2.7 | 0.005 |

| 2. They are coordinated to offer me good care | 77.4% | 8.8% | 13.8% | 69.9% | 13.4% | 16.7% | 0.048 | 7.5 ± 3.2 | 7.1 ± 3.3 | 0.15 |

| 3. They help me to find information online | 6.0% | 9.3% | 84.7% | 10.8% | 10.8% | 78.4% | 0.06 | 1.4 ± 2.6 | 1.8 ± 3.0 | 0.14 |

| 4. Now I know how to take better care of myself | 79.6% | 17.2% | 3.2% | 76.8% | 17.7% | 5.5% | 0.28 | 8.0 ± 2.2 | 7.8 ± 2.4 | 0.32 |

| 5. They ask about me and help me follow my treatment plan | 75.6% | 18.2% | 6.2% | 81.0% | 11.7% | 7.3% | 0.10 | 8.0 ± 2.7 | 8.0 ± 2.7 | 0.90 |

| 6. We set goals for leading a healthy life and controlling my disease | 76.0% | 14.7% | 9.3% | 76.2% | 15.0% | 8.8% | 0.53 | 7.7 ± 2.8 | 7.8 ± 2.7 | 0.70 |

| 7. I use the Internet and my mobile to consult my medical history | 7.8% | 6.8% | 85.4% | 6.3% | 5.9% | 87.8% | 0.35 | 1.2 ± 2.7 | 1.1 ± 2.4 | 0.58 |

| 8. They make sure I take my medication correctly | 71.7% | 13.3% | 15.0% | 74.3% | 14.3% | 11.4% | 0.31 | 7.5 ± 3.3 | 7.7 ± 3.0 | 0.41 |

| 9. They care about my well-being | 84.1 | 10.6 | 5.3 | 83.4 | 11.8 | 4.8 | 0.47 | 8.5 ± 2.4 | 8.3 ± 2.4 | 0.50 |

| 10. They inform me of health and social resources that can help me | 39.6 | 24.0 | 36.4 | 45.1 | 21.8 | 33.1 | 0.15 | 5.2 ± 6.7 | 5.4 ± 3.8 | 0.47 |

| 11. They encourage me to talk to other patients | 12.5 | 15.3 | 72.2 | 11.4 | 23.3 | 65.3 | 0.42 | 2.3 ± 3.1 | 2.5 ± 3.0 | 0.41 |

| 12. If hospitalised: they worry about me when I get home from hospital | 32.6 | 12.4 | 55.0 | 33.1 | 13.7 | 53.2 | 0.52 | 3.8 ± 4.3 | 4.0 ± 4.1 | 0.77 |

CAD: Advanced Diabetes Centre.

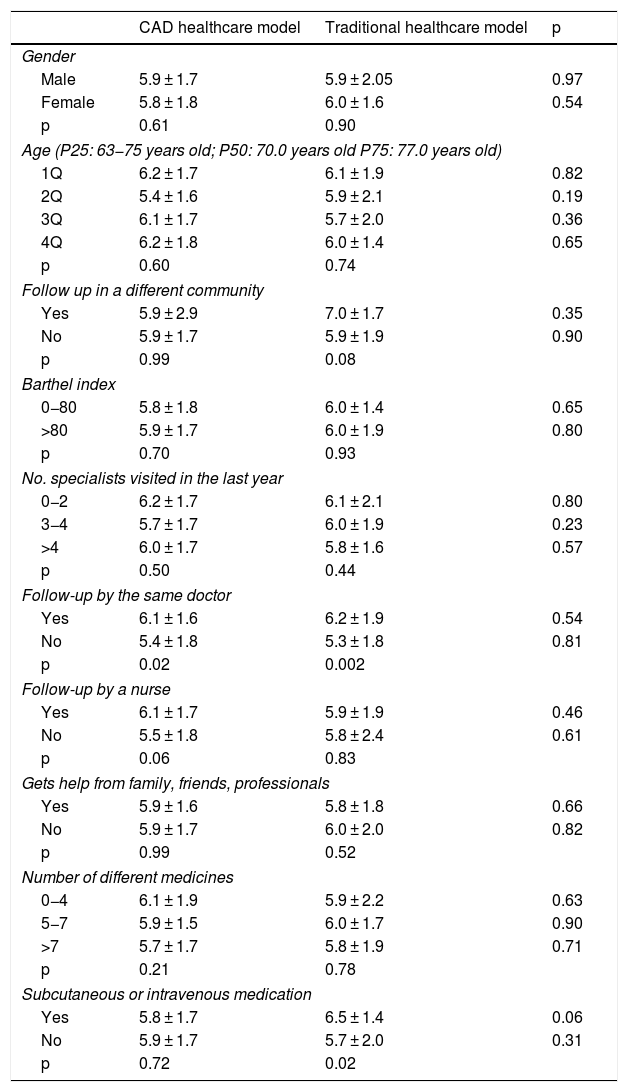

Table 3 shows the data referring to the IEXPAC questionnaire overall score in relation to different factors and according to the care model. Except for presenting higher scores in those patients who received subcutaneous or intravenous medication in the group treated under the traditional care model, the IEXPAC questionnaire overall score was independent of the different factors analysed (age, gender, follow-up in a different community, Barthel index, number of specialists visited in the last year, follow-up by the same doctor, follow-up by a nurse, receiving help from friends, family or professionals, number of different medicines and receiving subcutaneous or intravenous medication), as well as the care model.

Overall IEXPAC questionnaire score according to different factors by care model.

| CAD healthcare model | Traditional healthcare model | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||

| Male | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 5.9 ± 2.05 | 0.97 |

| Female | 5.8 ± 1.8 | 6.0 ± 1.6 | 0.54 |

| p | 0.61 | 0.90 | |

| Age (P25: 63−75 years old; P50: 70.0 years old P75: 77.0 years old) | |||

| 1Q | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 0.82 |

| 2Q | 5.4 ± 1.6 | 5.9 ± 2.1 | 0.19 |

| 3Q | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 2.0 | 0.36 |

| 4Q | 6.2 ± 1.8 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 0.65 |

| p | 0.60 | 0.74 | |

| Follow up in a different community | |||

| Yes | 5.9 ± 2.9 | 7.0 ± 1.7 | 0.35 |

| No | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 0.90 |

| p | 0.99 | 0.08 | |

| Barthel index | |||

| 0−80 | 5.8 ± 1.8 | 6.0 ± 1.4 | 0.65 |

| >80 | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.9 | 0.80 |

| p | 0.70 | 0.93 | |

| No. specialists visited in the last year | |||

| 0−2 | 6.2 ± 1.7 | 6.1 ± 2.1 | 0.80 |

| 3−4 | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 1.9 | 0.23 |

| >4 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 5.8 ± 1.6 | 0.57 |

| p | 0.50 | 0.44 | |

| Follow-up by the same doctor | |||

| Yes | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 6.2 ± 1.9 | 0.54 |

| No | 5.4 ± 1.8 | 5.3 ± 1.8 | 0.81 |

| p | 0.02 | 0.002 | |

| Follow-up by a nurse | |||

| Yes | 6.1 ± 1.7 | 5.9 ± 1.9 | 0.46 |

| No | 5.5 ± 1.8 | 5.8 ± 2.4 | 0.61 |

| p | 0.06 | 0.83 | |

| Gets help from family, friends, professionals | |||

| Yes | 5.9 ± 1.6 | 5.8 ± 1.8 | 0.66 |

| No | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 6.0 ± 2.0 | 0.82 |

| p | 0.99 | 0.52 | |

| Number of different medicines | |||

| 0−4 | 6.1 ± 1.9 | 5.9 ± 2.2 | 0.63 |

| 5−7 | 5.9 ± 1.5 | 6.0 ± 1.7 | 0.90 |

| >7 | 5.7 ± 1.7 | 5.8 ± 1.9 | 0.71 |

| p | 0.21 | 0.78 | |

| Subcutaneous or intravenous medication | |||

| Yes | 5.8 ± 1.7 | 6.5 ± 1.4 | 0.06 |

| No | 5.9 ± 1.7 | 5.7 ± 2.0 | 0.31 |

| p | 0.72 | 0.02 | |

CAD: Advanced Diabetes Centre.

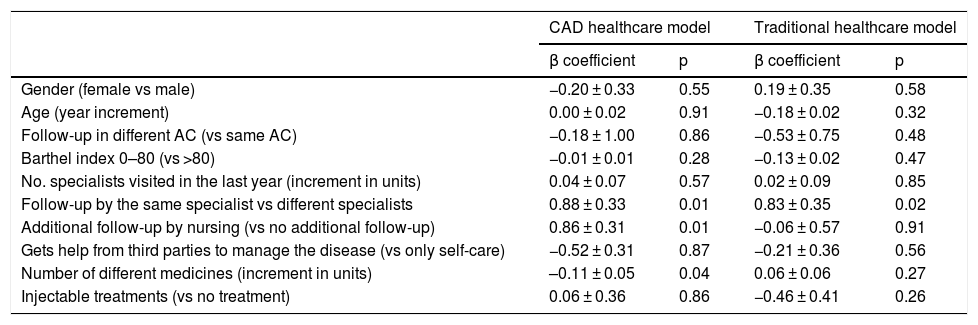

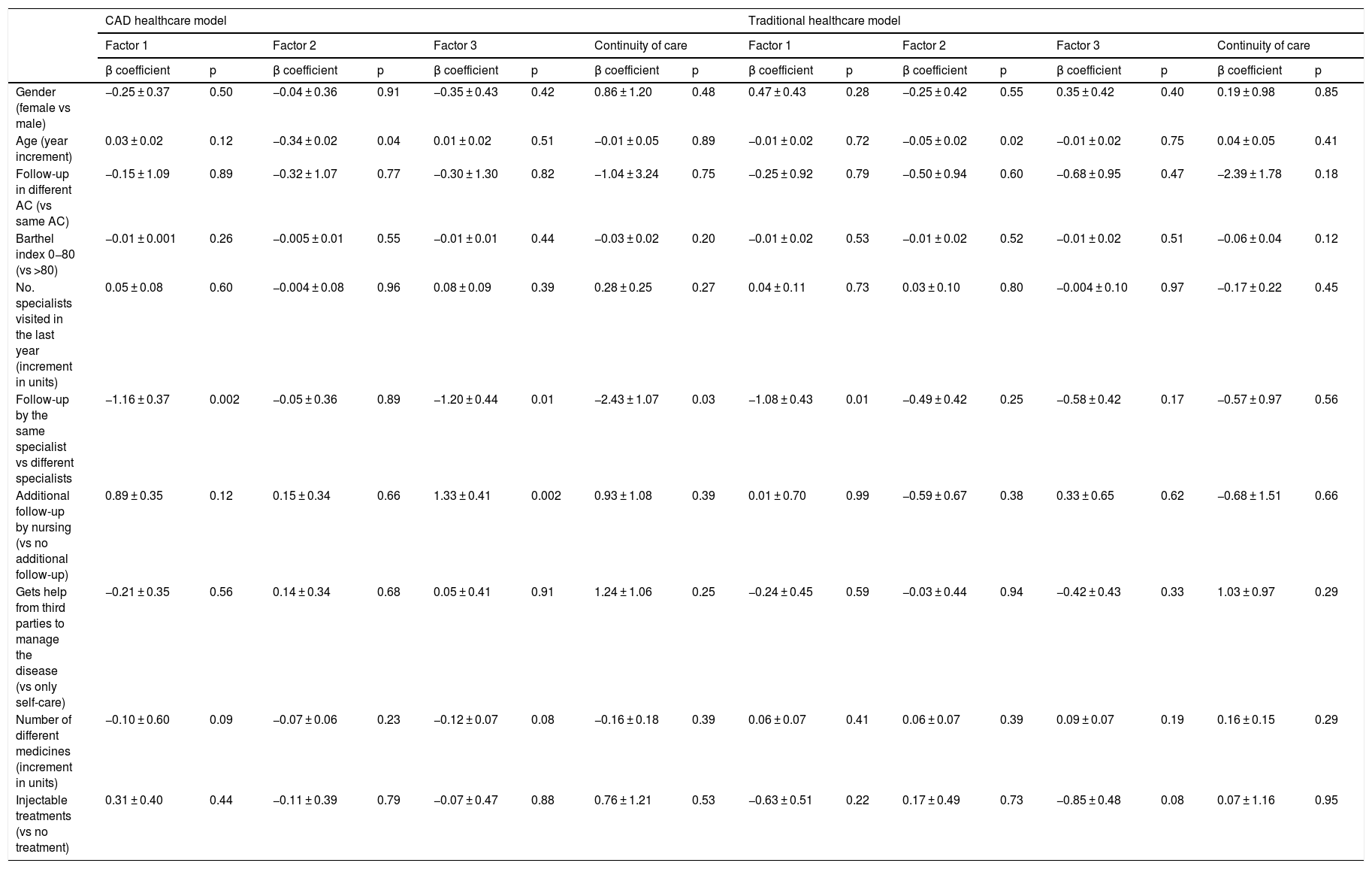

The results of the multivariate analysis according to the care model for the IEXPAC experience general score and for domains 1−3 and item 12, which assesses continuity of care, are shown in Tables 4 and 5. In the CAD centres, follow-up by the same specialist (p = 0.01) and additional follow-up by nurses (p = 0.01) were associated with a better experience (higher scores on the IEXPAC scale), while the administration of a greater number of medications was associated with a worse experience (p = 0.04). In contrast, in the traditional healthcare model centres, only follow-up carried out by the same specialist was associated with a better experience (p = 0.02). Regarding the variables related to productive interactions (domain 1), in both healthcare models follow-up by the same specialist was associated with a better experience (p = 0.002 and 0.01, respectively). Regarding the variables related to the new relationship model (domain 2), in both healthcare models older age was associated with a worse experience (p = 0.04 and 0.02, respectively). Regarding the variables related to self-care (domain 3), in the CAD group both follow-up by the same specialist (p = 0.01) and additional follow-up by nursing (p = 0.002) were associated with a better experience. Similarly, follow-up by the same specialist was associated with better continuity of care in the CAD group (p = 0.03).

Multivariate analysis for the IEXPAC experience general score by care model.

| CAD healthcare model | Traditional healthcare model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | |

| Gender (female vs male) | −0.20 ± 0.33 | 0.55 | 0.19 ± 0.35 | 0.58 |

| Age (year increment) | 0.00 ± 0.02 | 0.91 | −0.18 ± 0.02 | 0.32 |

| Follow-up in different AC (vs same AC) | −0.18 ± 1.00 | 0.86 | −0.53 ± 0.75 | 0.48 |

| Barthel index 0–80 (vs >80) | −0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.28 | −0.13 ± 0.02 | 0.47 |

| No. specialists visited in the last year (increment in units) | 0.04 ± 0.07 | 0.57 | 0.02 ± 0.09 | 0.85 |

| Follow-up by the same specialist vs different specialists | 0.88 ± 0.33 | 0.01 | 0.83 ± 0.35 | 0.02 |

| Additional follow-up by nursing (vs no additional follow-up) | 0.86 ± 0.31 | 0.01 | −0.06 ± 0.57 | 0.91 |

| Gets help from third parties to manage the disease (vs only self-care) | −0.52 ± 0.31 | 0.87 | −0.21 ± 0.36 | 0.56 |

| Number of different medicines (increment in units) | –0.11 ± 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.06 | 0.27 |

| Injectable treatments (vs no treatment) | 0.06 ± 0.36 | 0.86 | −0.46 ± 0.41 | 0.26 |

AC: Autonomous Communities; CAD: Advanced Diabetes Centre.

Multivariate analysis for factors 1–3 and continuity of care, by care model.

| CAD healthcare model | Traditional healthcare model | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Continuity of care | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | Continuity of care | |||||||||

| β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | β coefficient | p | |

| Gender (female vs male) | −0.25 ± 0.37 | 0.50 | −0.04 ± 0.36 | 0.91 | −0.35 ± 0.43 | 0.42 | 0.86 ± 1.20 | 0.48 | 0.47 ± 0.43 | 0.28 | −0.25 ± 0.42 | 0.55 | 0.35 ± 0.42 | 0.40 | 0.19 ± 0.98 | 0.85 |

| Age (year increment) | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.34 ± 0.02 | 0.04 | 0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.51 | −0.01 ± 0.05 | 0.89 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.72 | −0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.75 | 0.04 ± 0.05 | 0.41 |

| Follow-up in different AC (vs same AC) | −0.15 ± 1.09 | 0.89 | −0.32 ± 1.07 | 0.77 | −0.30 ± 1.30 | 0.82 | −1.04 ± 3.24 | 0.75 | −0.25 ± 0.92 | 0.79 | −0.50 ± 0.94 | 0.60 | −0.68 ± 0.95 | 0.47 | −2.39 ± 1.78 | 0.18 |

| Barthel index 0−80 (vs >80) | −0.01 ± 0.001 | 0.26 | −0.005 ± 0.01 | 0.55 | −0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.44 | −0.03 ± 0.02 | 0.20 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.53 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.52 | −0.01 ± 0.02 | 0.51 | −0.06 ± 0.04 | 0.12 |

| No. specialists visited in the last year (increment in units) | 0.05 ± 0.08 | 0.60 | −0.004 ± 0.08 | 0.96 | 0.08 ± 0.09 | 0.39 | 0.28 ± 0.25 | 0.27 | 0.04 ± 0.11 | 0.73 | 0.03 ± 0.10 | 0.80 | −0.004 ± 0.10 | 0.97 | −0.17 ± 0.22 | 0.45 |

| Follow-up by the same specialist vs different specialists | −1.16 ± 0.37 | 0.002 | −0.05 ± 0.36 | 0.89 | −1.20 ± 0.44 | 0.01 | −2.43 ± 1.07 | 0.03 | −1.08 ± 0.43 | 0.01 | −0.49 ± 0.42 | 0.25 | −0.58 ± 0.42 | 0.17 | −0.57 ± 0.97 | 0.56 |

| Additional follow-up by nursing (vs no additional follow-up) | 0.89 ± 0.35 | 0.12 | 0.15 ± 0.34 | 0.66 | 1.33 ± 0.41 | 0.002 | 0.93 ± 1.08 | 0.39 | 0.01 ± 0.70 | 0.99 | −0.59 ± 0.67 | 0.38 | 0.33 ± 0.65 | 0.62 | −0.68 ± 1.51 | 0.66 |

| Gets help from third parties to manage the disease (vs only self-care) | −0.21 ± 0.35 | 0.56 | 0.14 ± 0.34 | 0.68 | 0.05 ± 0.41 | 0.91 | 1.24 ± 1.06 | 0.25 | −0.24 ± 0.45 | 0.59 | −0.03 ± 0.44 | 0.94 | −0.42 ± 0.43 | 0.33 | 1.03 ± 0.97 | 0.29 |

| Number of different medicines (increment in units) | −0.10 ± 0.60 | 0.09 | −0.07 ± 0.06 | 0.23 | −0.12 ± 0.07 | 0.08 | −0.16 ± 0.18 | 0.39 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.41 | 0.06 ± 0.07 | 0.39 | 0.09 ± 0.07 | 0.19 | 0.16 ± 0.15 | 0.29 |

| Injectable treatments (vs no treatment) | 0.31 ± 0.40 | 0.44 | −0.11 ± 0.39 | 0.79 | −0.07 ± 0.47 | 0.88 | 0.76 ± 1.21 | 0.53 | −0.63 ± 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.17 ± 0.49 | 0.73 | −0.85 ± 0.48 | 0.08 | 0.07 ± 1.16 | 0.95 |

The data from our study show that IEXPAC can be a useful tool for assessing the healthcare experience of patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, as well as for identifying areas for improvement, in addition to being able to analyse differences between care models (CAD vs traditional model). In fact, compared to other questionnaires, IEXPAC provides a more comprehensive assessment of healthcare, including new technologies and forms of relationship between patients.11,12,17–20

The patients analysed in our study, who by inclusion criteria were patients with type 2 diabetes with cardiovascular or renal complications, were elderly, with a higher percentage of men, and were receiving multiple medications. The use of health services (visits to Primary Care and other specialists, visits to the emergency room and previous hospitalisations) was high in this population, which indicates the high risk of complications in these patients. In fact, previous studies carried out in Spain show that patients with type 2 diabetes have several comorbidities and a high risk of hospitalisation.21,22 The clinical profile of the patients analysed was quite similar, regardless of the type of care they received (CAD model vs traditional model). Although in both groups there was a high rate of doctors’ visits and more than 85% reported receiving sufficient information from their healthcare professionals in general, in the CAD group patients were more frequently seen by the same doctor and received more information regarding diet, although they received less nursing follow-up.

Regarding the general experience of patients with healthcare, the mean score was around 6, regardless of the healthcare model. Considering that the best theoretical chronic patient experience regarding their healthcare is a score of 10, there is still significant scope for improvement in the overall patient experience. This is especially striking when the data related to the new healthcare model (Internet use, communicating with other patients) are analysed, and within the variables related to self-care and receiving information about health and social resources. However, CAD patients scored significantly better on item 1 (8.4 ± 2.1 vs 7.8 ± 2.7; p = 0.005), indicating that in this care model, healthcare professionals may be more involved in understanding the lifestyle of their patients, which is a very important factor in offering patient-centred care. Likewise, all the items in the IEXPAC questionnaire constitute an opportunity to establish new lines of work to improve care, both for the CAD model and for the traditional healthcare model.

Several studies have shown that the design and implementation of education programmes for patients, both online and with new technologies (mobile applications, etc.), can improve knowledge of the disease and its control.23 Taking into account that a significant proportion of patients with diabetes do not feel adequately informed about their disease,24 measures are needed to improve healthcare by empowering patients through access to information and the use of new technologies and the Internet. However, given that our study showed that older age was associated with a worse experience with the new relationship model, regardless of the care model, additional efforts will have to be made for the elderly to simplify new technologies and make them more affordable for this population, which is increasingly prevalent among patients with type 2 diabetes.

Another relevant piece of data from the study was the low participation of patients with type 2 diabetes in patient associations. Taking into account the high prevalence of diabetes and that the time healthcare professionals have for educational tasks is limited, looking for alternatives that are effective with the available resources should be one of the objectives of healthcare.25 In this sense, it has been demonstrated that fostering contact with other patients with different experiences can improve health outcomes, so it should be implemented routinely, representing a potential for healthcare improvement in general.26

The multivariate analysis confirmed that follow-up by the same specialist was associated with a better patient experience with the healthcare received in the two care models. This is because follow-up by the same specialist allows for improved communication and trust with the patient, and in turn improved health outcomes (changes in lifestyle, greater adherence to treatment, quality of life).27 Similarly, follow-up by the same specialist was associated with better continuity of care in the CAD group. Ensuring adequate continuity of care is essential to avoid unnecessary errors in the transition after hospital discharge, and it seems that ensuring that the same specialist continues to treat the patient could contribute to this.28 It would be interesting to carry out studies that review and compare early follow-up protocols after discharge in the two care models, with the aim of optimising them as well as evaluating their impact on the number of re-admissions. Additionally, nursing follow-up was also associated with a better patient experience, but only in the CAD group. Therefore, this seems to indicate that in the CAD care model, patients value the presence of nursing more than in the traditional care model, where despite having observed longer follow-up by nursing, no association was found between patient experience and follow-up by nurses. Encouraging additional follow-up and communication with the nursing staff should be another of the pillars that may improve the overall patient experience.29 Therefore, both the promotion of follow-up by the same specialist and the involvement of nurses in the management of diabetes constitute an opportunity for improvement in the two healthcare models and should be the main objectives in these centres. In contrast, higher medication use was associated with poorer healthcare experience. It would be interesting to delve into the causes of this association further, with the aim of determining whether it could be due to polypharmacy or perhaps due to patient characteristics associated with combination therapy in the CAD care model.

In our study, approximately 45% of the patients treated in CADs and a third of the patients treated according to the traditional model reported a good quality of life. Previous studies have demonstrated that diabetes negatively impacts quality of life,5,10,28 so it is important to try to understand and empathise with the patients' lifestyles (IEXPAC item 1 result) to increase success in the management of these patients. In this regard, it seems that CAD model patients have a better perception of their quality of life than patients treated under the traditional model, with a higher proportion of high scores and a higher mean value on the visual analogue scale. This may indicate that the actions taken by healthcare professionals in this care model could be more oriented towards positively contributing to an improvement in the quality of life of patients with type 2 diabetes.

This study has some limitations that need to be discussed.12 Given the characteristics of the questionnaire, the clinical profile of the patients was not fully defined, which could have had some impact on the patients' experience with healthcare. In addition, typically in this type of study it is the most motivated patients who are usually included, so it is very possible that, although the patients were included consecutively to minimise this possible limitation, the actual results of the population with diabetes were worse than those reported in this study. In total, 23 centres with the CAD healthcare model and 25 centres with the traditional healthcare model participated in this study. To avoid biases, special care was taken when selecting centres, so that they were balanced, in Health Districts with the same characteristics, and could be comparable. The study brings to light some aspects that can be modified to improve the experience, making it necessary to further evaluate the effects of the CAD model of care on different aspects of the healthcare of patients with type 2 diabetes.

In conclusion, our data suggest that there is room for improvement in the overall healthcare experience of patients with type 2 diabetes. Patients seen in CAD centres have a better score on the quality of life scale and value nursing follow-up more, although there are still areas for improvement.

AuthorshipAGG, KFC and GF participated in the planning and implementation of the study.

KFC coordinated the implementation of the study.

GF and DOB participated in the conception and design of the study.

KFC and DOB participated in the interpretation of the results.

KFC collaborated in the writing of the first draft.

SAM, VGV, MJFA, JLAJ, MCVA and JFZN participated in data collection.

AGG, KFC, DOB, RLR and GF provided substantive suggestions for revision and critically reviewed subsequent revisions of the manuscript.

All authors reviewed and approved the final version.

FundingThis study was funded by Merck Sharp & Dohme España, a subsidiary of Merck & Co., Inc., Kenilworth, NJ, USA.

Conflicts of interestDOB received fees for conferences and participation in lectures from MSD, Sanofi, NovoNordisk and Lilly.

AGG, KFC, RLR and GF are employed full time at Merck Sharp & Dohme, España.

The remaining authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest related to the drafting of this document.

This study is endorsed by patient associations: Federación Española de Diabetes (FEDE) [Spanish Diabetes Federation], Coordinadora Nacional de Artritis (CONARTRITIS) [National Arthritis Coordinator], Asociación de Enfermos de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa de España (ACCU España) [Spanish Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Patients Association] and Sociedad Española Interdisciplinaria del SIDA (SEISIDA) [Spanish Interdisciplinary AIDS Society], which actively participated in the design of the questionnaires. The authors would like to thank all the patients who completed the questionnaire and researchers who participated in the study, as well as the IEXPAC working group for providing such a valuable tool. Editorial assistance was provided by Content Ed Net, with funding from MSD España.

Please cite this article as: Gómez-García A, Ferreira de Campos K, Orozco-Beltrán D, Artola-Menéndez S, Grahit-Vidosa V, Fierro-Alario MJ, et al. Impacto de los Centros Avanzados de Diabetes en la experiencia de los pacientes con diabetes tipo 2 con la atención sanitaria mediante la herramienta IEXPAC. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2021;68:416–427.