Postparathyroidectomy normocalcemic hyperparathyroidism (PPNCHPPT) is a frequent situation for which we have no information in our country. The objective is to know our prevalence of PPNCHPPT, the associated etiological factors, the predictive markers, the treatment administered and the evolution.

Patients and methodRetrospective observational cross-sectional study on 42 patients. Twelve patients with PPNCHPPT and 30 without PPNCHPPT are compared.

ResultsHPPTNCPP prevalence: 28.6%. Etiological factors: vitamin D deficiency: 75%; bone remineralization: 16.7%; renal failure: 16.7%; hypercalciruria: 8.3%. No change in the set point of calcium-mediated parathormone (PTH) secretion was observed, but an increase in the preoperative PTH/albumin-corrected calcium (ACC) ratio was observed. Predictive markers: PTH/ACC ratio (AUC 0.947; sensitivity 100%, specificity 78.9%) and PTH (AUC 0.914; sensitivity 100%, specificity 73.7%) one week postparathyroidectomy. Evolution: follow-up 30 ± 16.3 months: 50% normalized PTH and 8.3% had recurrence of hyperparathyroidism. Patients with PPNCHPPT less frequently received preoperative treatment with bisphosphonates and postoperative treatment with calcium salts.

ConclusionsThis is the first study in our country that demonstrates a mean prevalence of PPNCHPPT, mainly related to a vitamin D deficiency and a probable resistance to the action of PTH, which can be predicted by the PTH/ACC ratio and PTH a week post-intervention and often evolves normalizing the PTH. We disagree with the etiological effect of hypercalciuria and the change in the PTH/calcemia regulation set point, and we acknowledge the scant treatment administered with calcium salts in the postoperative period.

El hiperparatiroidismo normocalcémico postparatiroidectomía (HPPTNCPP) es una situación frecuente de la que no tenemos información de nuestro país. El objetivo es conocer nuestra prevalencia del HPPTNCPP, los factores etiológicos asociados, los marcadores predictivos, el tratamiento administrado y la evolución.

Pacientes y métodoEstudio retrospectivo observacional transversal sobre 42 pacientes. Se comparan 12 pacientes con HPPTNCPP y 30 sin HPPTNCPP.

ResultadosPrevalencia del HPPTNCPP: 28,6%. Factores etiológicos: déficit de vitamina D: 75%; remineralización ósea: 16,7%; insuficiencia renal: 16,7%; hipercalciuria: 8,3%. No se observó cambio en el punto de regulación de la secreción de parathormona (PTH) mediada por la calcemia, pero sí un aumento del cociente PTH/calcio corregido por albúmina (CCA) preoperatorio. Marcadores predictivos: cociente PTH/CCA (AUC 0,947; sensibilidad 100%, especificidad 78,9%) y PTH (AUC 0,914; sensibilidad 100%, especificidad 73,7%) una semana postparatiroidectomía. Evolución: seguimiento 30 ± 16,3 meses: 50% normalizó PTH y 8,3% tuvo recurrencia del hiperparatiroidismo. Los pacientes con HPPTNCPP recibieron con menor frecuencia tratamiento preoperatorio con bifosfonatos y posoperatorio con sales de calcio.

ConclusionesEs el primer estudio en nuestro país que demuestra una prevalencia media del HPPTNCPP, relacionado principalmente con un déficit de vitamina D y con una probable resistencia a la acción de la PTH, que puede ser predicho mediante el cociente PTH/CCA y la PTH a la semana postintervención, que con frecuencia evoluciona normalizando la PTH. Disentimos del efecto etiológico de la hipercalciuria y del cambio en el punto de regulación PTH/calcemia, y reconocemos el escaso tratamiento administrado con sales de calcio en el posoperatorio.

The biochemical cure of hyperparathyroidism (HPPT) after surgical treatment is confirmed when parathyroid hormone (PTH) and albumin-adjusted calcium (AAC) levels remain normal for at least six months after surgery. Hypercalcaemia with elevated PTH in this time period indicates persistent HPPT, and hypercalcaemia observed beyond six months after a period of normocalcaemia is considered to be recurrent HPPT. An intermediate situation between the cure and persistence of HPPT results from elevated PTH with normocalcaemia following the curative surgical resection of a primary HPPT (PPNCHPPT or post-parathyroidectomy normocalcaemic hyperparathyroidism). On average, this disorder has a prevalence of 30% outside of our setting.1–3

PPNCHPPT represents a complex clinical situation whose pathological significance has not been sufficiently defined and for which there is no consensus on follow-up and treatment.1,2,4,5 At this moment in time there is no evidence that PPNCHPPT is a consequence of surgical failure.1,2 In 30%–60% of these patients, PTH levels will normalise within 12–18 months of the procedure, and in the remainder this may mean an autonomisation of PTH secretion that should be monitored to assess for the recurrence of HPPT.1,2,6−9

Some predictive markers of PPNCHPPT have been described, although not unanimously,1,2,8,10–15 and a number of potentially responsible causes such as vitamin D deficiency, bone remineralisation syndrome, inadequate calcium intake or absorption, chronic kidney disease and hypercalciuria have been hypothesised. A further two aetiopathogenic mechanisms have also been proposed: an increase in the PTH secretion regulation point prompted by changes in the calcium-sensing receptors in the remaining parathyroid glands and a reduction in peripheral sensitivity to PTH.1,2,4,7–9,10–13,16–21

The objective of this study is to determine, in our setting, the prevalence of PPNCHPPT in the first six months after a successful parathyroidectomy for a single adenoma, to evaluate the possible aetiological factors and associated predictive markers, the treatment given and outcome after more than 12 months of follow-up.

Material and methodsThis was a retrospective observational study based on routine clinical practice in a hospital setting. In total, 42 patients undergoing a parathyroidectomy between May 2017 and May 2022, with anatomopathological findings of single parathyroid adenoma were included to compare those with PPNCHPPT and those who had normal post-parathyroidectomy PTH and calcium levels. All of them had a postoperative follow-up of more than six months, and those with PPNCHPPT had a follow-up of more than 12 months. Patients who exhibited a reduction in PTH of less than 60% in the first 24 h post-parathyroidectomy were excluded on the grounds that the procedure may not have been successful,10 as were those who received preoperative cinacalcet treatment, which may have modified PTH values and the calcium-mediated PTH secretion regulation point. The study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee of the Fundació Assistencial Mútua de Terrassa.

The variables collected from the clinical history were: personal data (sex, age and weight at the time of the parathyroidectomy), results of the dorsolumbar spine bone X-ray and preoperative bone densitometry; change over time of preoperative and postoperative analytical parameters in the first eight and 24 h, first week, first month, sixth month and subsequent follow-up of PTH, AAC, calcifediol, 24-h urinary calcium, plasma creatinine and glomerular filtration rate estimated according to the 2009 CKD-EPI creatinine equation, and plasma phosphate and magnesium in cases of hungry bone syndrome; preoperative and postoperative treatment with calcium salts, vitamin D supplements and bone antiresorptive agents, and patient follow-up time.

The primary endpoints were:

- -

Prevalence of PPNCHPPT identified by lab test at six months post-parathyroidectomy.

- -

Possible aetiological factors associated with PPNCHPPT2:

- o

Bone remineralisation syndrome: defined according to the appearance of hungry bone syndrome (AAC of less than 8 mg/dL in the first 24 h of the postoperative period prolonged for more than four days with hypophosphataemia and hypomagnesaemia) and/or pathological fractures in the dorsal or lumbar spine and/or bone densitometry prior to surgery with osteoporosis values in the lumbar spine and/or femur.21,22

- o

Calcifediol deficiency six months after the parathyroidectomy: plasma calcifediol less than 30 ng/mL.

- o

Kidney failure six months after parathyroidectomy: estimated glomerular filtration rate less than 60 mL/min.

- o

Hypercalciuria in the first six months after parathyroidectomy: 24-h urinary calcium greater than 4 mg/kg/day.23

- o

- -

Possible aetiopathogenic mechanisms associated with PPNCHPPT:

- o

Change in the calcium-mediated PTH secretion regulation point, evaluated by the percentage decrease in PTH and AAC in the first 24 h after surgery.6

- o

Decreased peripheral sensitivity to PTH evaluated as the preoperative PTH/AAC ratio.

- o

- -

Possible predictive markers of PPNCHPPT2:

- o

Patient age.

- o

PTH, AAC and calcifediol concentrations preoperatively and during the first six months postoperative.

- o

PTH ratios over time:

- •

Intraoperative post-exeresis PTH/intraoperative pre-exeresis PTH ratio.

- •

8-h post-exeresis PTH/preoperative PTH ratio.

- •

24-h post-exeresis PTH/preoperative PTH ratio.

- •

24-h post-exeresis PTH/8-h post-exeresis PTH ratio.

- •

- o

Preoperative and postoperative PTH/AAC ratio.

- o

Secondary endpoints were outcome after six or more months of follow-up of PPNCHPPT evaluated as normalisation of PTH (at least the last two PTH tests are normal), persistence of PTH elevation or recurrence of HPPT and the effect of treatment with calcium salts, vitamin D supplements and/or bone antiresorptive agents.

Calcium levels were determined using the 5-nitro-5'-methyl-BAPTA method; urinary calcium with o-cresolphthalein complexone, plasma albumin using bromocresol green and intact PTH and calcifediol using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. The reference values for calcium were 8.6–10.0 mg/dL, with a coefficient of variation of 0.61%, while for intact PTH they were 15.0–65.7 pg/mL, with a coefficient of variation of 3.05% and an assay sensitivity of 5.5 pg/mL. All the other biochemical parameters were performed by standard procedures. In the dorsal and lumbar spine X-rays, the presence of vertebral fractures was assessed by a reduction of 20% or more in the anterior, middle or posterior height of the vertebral body. Bone mineral density in the lumbar spine (L2–L4) and proximal femur was assessed by dual X-ray absorptiometry (Lunar PRODIGY device).

A descriptive analysis of the variables collected was performed. The univariate analysis of differences between continuous and categorical variables was analysed with the Student's t-test, and the relationship between the categorical variables with the Chi-square or Fisher's F-test. A binary logistic regression analysis was performed to investigate the independence of the predictive variables for PPNCHPPT. ROC curves were generated to determine sensitivity and specificity in predicting PPNCHPPT. Statistical significance was established at P < .05 (2-tailed). The statistical analysis was performed using the software Epidat, version 3.1 (Servizo Galego de Saúde [Galician Health Service], Galicia, Spain).

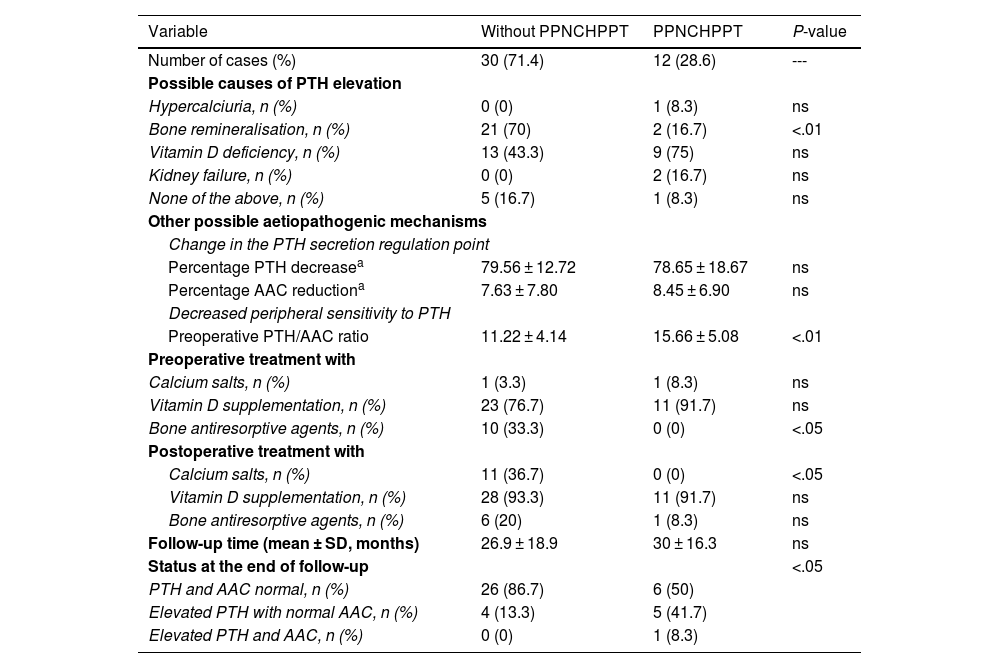

ResultsIn total, 42 patients were included, 39 women (92.9%) and three men (7.1%), with a mean age of 58.6 ± 11 years. The prevalence of patients with PPNCHPPT was 12 cases (28.6%). The related causes, treatment received and outcome are detailed in Table 1.

Prevalence, possible causes, treatment received and outcome of patients with PPNCHPPT compared to patients without PPNCHPPT after parathyroidectomy.

| Variable | Without PPNCHPPT | PPNCHPPT | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of cases (%) | 30 (71.4) | 12 (28.6) | --- |

| Possible causes of PTH elevation | |||

| Hypercalciuria, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | ns |

| Bone remineralisation, n (%) | 21 (70) | 2 (16.7) | <.01 |

| Vitamin D deficiency, n (%) | 13 (43.3) | 9 (75) | ns |

| Kidney failure, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (16.7) | ns |

| None of the above, n (%) | 5 (16.7) | 1 (8.3) | ns |

| Other possible aetiopathogenic mechanisms | |||

| Change in the PTH secretion regulation point | |||

| Percentage PTH decreasea | 79.56 ± 12.72 | 78.65 ± 18.67 | ns |

| Percentage AAC reductiona | 7.63 ± 7.80 | 8.45 ± 6.90 | ns |

| Decreased peripheral sensitivity to PTH | |||

| Preoperative PTH/AAC ratio | 11.22 ± 4.14 | 15.66 ± 5.08 | <.01 |

| Preoperative treatment with | |||

| Calcium salts, n (%) | 1 (3.3) | 1 (8.3) | ns |

| Vitamin D supplementation, n (%) | 23 (76.7) | 11 (91.7) | ns |

| Bone antiresorptive agents, n (%) | 10 (33.3) | 0 (0) | <.05 |

| Postoperative treatment with | |||

| Calcium salts, n (%) | 11 (36.7) | 0 (0) | <.05 |

| Vitamin D supplementation, n (%) | 28 (93.3) | 11 (91.7) | ns |

| Bone antiresorptive agents, n (%) | 6 (20) | 1 (8.3) | ns |

| Follow-up time (mean ± SD, months) | 26.9 ± 18.9 | 30 ± 16.3 | ns |

| Status at the end of follow-up | <.05 | ||

| PTH and AAC normal, n (%) | 26 (86.7) | 6 (50) | |

| Elevated PTH with normal AAC, n (%) | 4 (13.3) | 5 (41.7) | |

| Elevated PTH and AAC, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (8.3) | |

There were no cases with postoperative hungry bone syndrome among the remineralisation syndrome cases. More than one cause was identified in some patients: in the group of patients with PPNCHPPT there was one case of hypercalciuria and vitamin D deficiency and one case of remineralisation and vitamin D deficiency, and in the group of patients without PPNCHPPT there were nine cases of vitamin D deficiency and remineralisation. All the bone antiresorptive agents administered were bisphosphonates.

Regarding status at the end of follow-up, in the non-PPNCHPPT group there were four cases of normocalcaemic HPPT as a consequence of vitamin D deficiency. In the PPNCHPPT group, there was only one recurrence of HPPT in one patient with chronic renal failure, and in the 5 cases that persisted with elevated PTH and normal calcium at the end of follow-up, the causes recognised were remineralisation in one case, vitamin D deficiency in two cases, hypercalciuria and vitamin D deficiency in one case and vitamin D deficiency and remineralisation in one case; no patient received preoperative treatment with calcium salts or bisphosphonates, although all cases were given vitamin D supplements, and in the postoperative period no patient had received treatment with calcium salts, four received vitamin D supplements and one bisphosphonates.

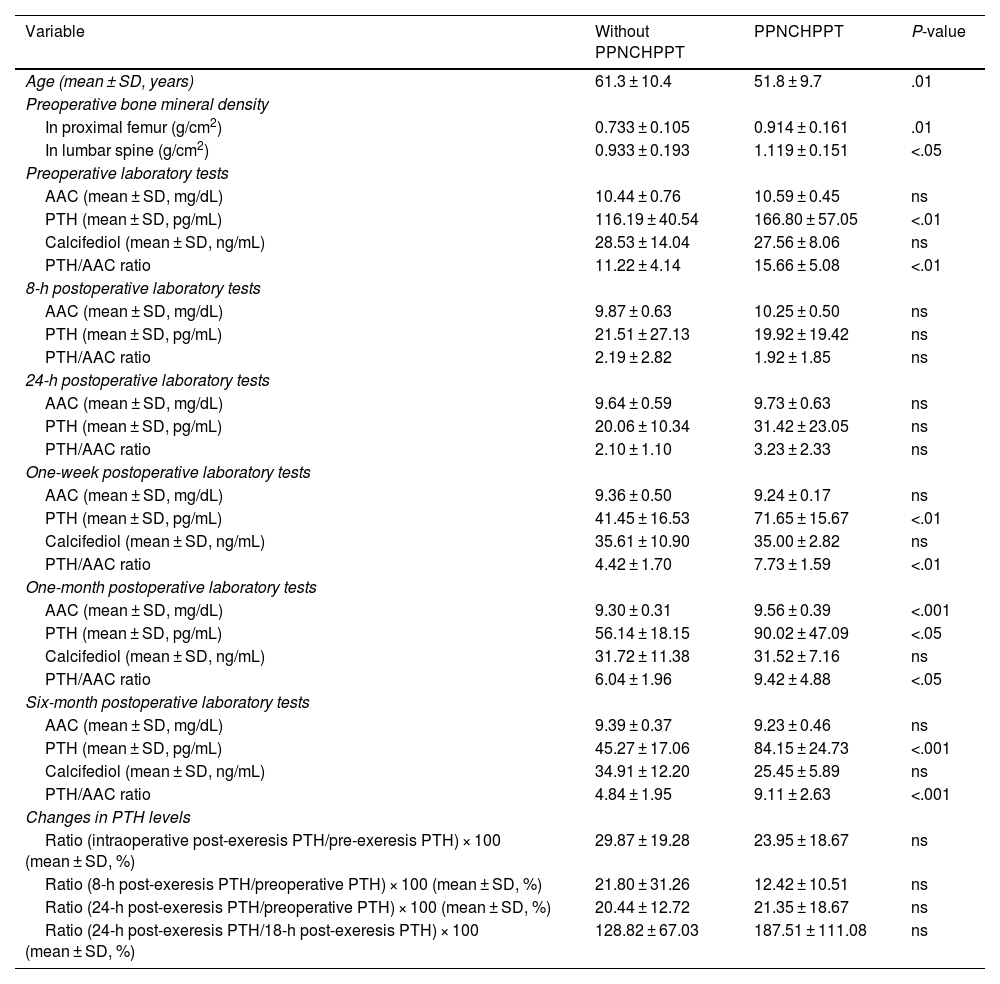

Table 2 details the possible predictive markers for PPNCHPPT. In the logistic regression analysis, only the one-week post-surgery PTH/AAC ratio variable was independently associated with PPNCHPPT (odds ratio 3.929, 95% CI: 1.054–14.647; P < .05). When this variable was extracted from the model, the one-week post-surgery PTH variable was the only variable independently associated with PPNCHPPT (odds ratio 1.130, 95% CI: 1.002–1.275; P < .05).

Possible predictive factors of PPNCHPPT.

| Variable | Without PPNCHPPT | PPNCHPPT | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD, years) | 61.3 ± 10.4 | 51.8 ± 9.7 | .01 |

| Preoperative bone mineral density | |||

| In proximal femur (g/cm2) | 0.733 ± 0.105 | 0.914 ± 0.161 | .01 |

| In lumbar spine (g/cm2) | 0.933 ± 0.193 | 1.119 ± 0.151 | <.05 |

| Preoperative laboratory tests | |||

| AAC (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 10.44 ± 0.76 | 10.59 ± 0.45 | ns |

| PTH (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 116.19 ± 40.54 | 166.80 ± 57.05 | <.01 |

| Calcifediol (mean ± SD, ng/mL) | 28.53 ± 14.04 | 27.56 ± 8.06 | ns |

| PTH/AAC ratio | 11.22 ± 4.14 | 15.66 ± 5.08 | <.01 |

| 8-h postoperative laboratory tests | |||

| AAC (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 9.87 ± 0.63 | 10.25 ± 0.50 | ns |

| PTH (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 21.51 ± 27.13 | 19.92 ± 19.42 | ns |

| PTH/AAC ratio | 2.19 ± 2.82 | 1.92 ± 1.85 | ns |

| 24-h postoperative laboratory tests | |||

| AAC (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 9.64 ± 0.59 | 9.73 ± 0.63 | ns |

| PTH (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 20.06 ± 10.34 | 31.42 ± 23.05 | ns |

| PTH/AAC ratio | 2.10 ± 1.10 | 3.23 ± 2.33 | ns |

| One-week postoperative laboratory tests | |||

| AAC (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 9.36 ± 0.50 | 9.24 ± 0.17 | ns |

| PTH (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 41.45 ± 16.53 | 71.65 ± 15.67 | <.01 |

| Calcifediol (mean ± SD, ng/mL) | 35.61 ± 10.90 | 35.00 ± 2.82 | ns |

| PTH/AAC ratio | 4.42 ± 1.70 | 7.73 ± 1.59 | <.01 |

| One-month postoperative laboratory tests | |||

| AAC (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 9.30 ± 0.31 | 9.56 ± 0.39 | <.001 |

| PTH (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 56.14 ± 18.15 | 90.02 ± 47.09 | <.05 |

| Calcifediol (mean ± SD, ng/mL) | 31.72 ± 11.38 | 31.52 ± 7.16 | ns |

| PTH/AAC ratio | 6.04 ± 1.96 | 9.42 ± 4.88 | <.05 |

| Six-month postoperative laboratory tests | |||

| AAC (mean ± SD, mg/dL) | 9.39 ± 0.37 | 9.23 ± 0.46 | ns |

| PTH (mean ± SD, pg/mL) | 45.27 ± 17.06 | 84.15 ± 24.73 | <.001 |

| Calcifediol (mean ± SD, ng/mL) | 34.91 ± 12.20 | 25.45 ± 5.89 | ns |

| PTH/AAC ratio | 4.84 ± 1.95 | 9.11 ± 2.63 | <.001 |

| Changes in PTH levels | |||

| Ratio (intraoperative post-exeresis PTH/pre-exeresis PTH) × 100 (mean ± SD, %) | 29.87 ± 19.28 | 23.95 ± 18.67 | ns |

| Ratio (8-h post-exeresis PTH/preoperative PTH) × 100 (mean ± SD, %) | 21.80 ± 31.26 | 12.42 ± 10.51 | ns |

| Ratio (24-h post-exeresis PTH/preoperative PTH) × 100 (mean ± SD, %) | 20.44 ± 12.72 | 21.35 ± 18.67 | ns |

| Ratio (24-h post-exeresis PTH/18-h post-exeresis PTH) × 100 (mean ± SD, %) | 128.82 ± 67.03 | 187.51 ± 111.08 | ns |

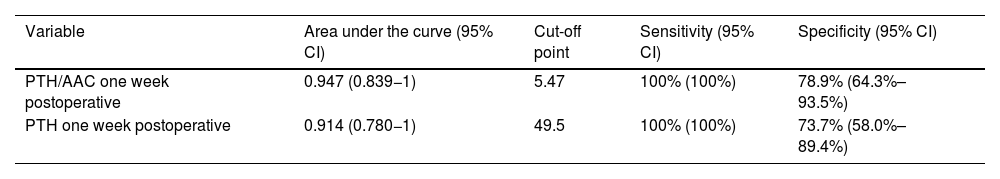

In the ROC curves to distinguish between patients with and without PPNCHPPT, the variables with the largest area under the curve, with a similar magnitude, were the PTH/AAC ratio and PTH, both at one-week post-surgery (Table 3).

Variables with predictive power to distinguish between patients with and without PPNCHPPT.

| Variable | Area under the curve (95% CI) | Cut-off point | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTH/AAC one week postoperative | 0.947 (0.839−1) | 5.47 | 100% (100%) | 78.9% (64.3%–93.5%) |

| PTH one week postoperative | 0.914 (0.780−1) | 49.5 | 100% (100%) | 73.7% (58.0%–89.4%) |

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first series of patients in our country in whom PPNCHPPT is analysed. The prevalence of 28.6% found is in line with previously documented series, although it should be noted that the reference range for this prevalence is very broad, from 8% to 44%.1,2,5–15,19,24 The reason for this disparity is unknown, but it may have to do with the cause of the PPNCHPPT that is not always easy to detect or to assess, which in our case proved to be predominantly vitamin D deficiency.

Most of the previous studies assess only some of the aetiologies responsible for PPNCHPPT, so there are no data on the actual incidence of each one, and comparisons cannot be drawn. Vitamin D deficiency is common and occurs more frequently in patients with HPPT due to increased vitamin D catabolism, which in turn can lead to secondary HPPT.1,6,11,12,15 In our series, it proved to be the most frequent aetiological factor related to PPNCHPPT, and was less present, albeit without statistical significance, perhaps because of the small number of cases in patients without PPNCHPPT. The vast majority of patients in each group received preoperative and postoperative treatment with vitamin D supplementation and their levels normalised within the first month, although in the group of patients with PPNCHPPT, levels fell by the sixth month post-parathyroidectomy, which could be reflected in a supranormal rise in PTH.

Bone remineralisation can be a very influential factor in PPNCHPPT and its effect can last between one and four years.8,10,11,21 This can be explained by the deposition of calcium salts in the bone, which leads to a decrease in serum calcium, resulting in elevated PTH levels to maintain normal extracellular calcium.2 The significant densitometric improvement in osteoporosis one year after parathyroidectomy in patients with primary HPPT provides valuable evidence of the bone remineralisation that occurs in these cases.25 The classic hungry bone syndrome, the ultimate example of bone remineralisation, with acute post-surgical presentation, is a rare occurrence not usually documented in series of patients with primary HPPT in recent decades due to its early diagnosis.11,21 The definition of bone remineralisation syndrome is not very precise, as it is based on certain characteristics associated with bone demineralisation, such as the presence of pathological fractures, lower bone mineral density, elevated alkaline phosphatase or osteocalcin levels, lower postoperative calcium and higher postoperative PTH, improved biochemical profile of PTH and calcium with treatment based on calcium salts with or without vitamin D supplementation, and its tendency to post-parathyroidectomy evolutionary extinction. In the actual clinical practice of patients with HPPT, we have sufficient densitometric, radiological and clinical data on pathological fractures to be able to justify a bone remineralisation phenomenon. However, there is no validated, accurate and stratified way of recognising it, whereby “less severe” forms of remineralisation may go undetected. In our series, bone remineralisation based on densitometric criteria of osteoporosis with or without pathological fractures was recognised in a small proportion of patients with PPNCHPPT and was surprisingly more frequent in the group of patients without PPNCHPPT, probably influenced by their older age; the higher frequency of preoperative treatment with bone antiresorptive agents and postoperative treatment with calcium salts may have helped to prevent supranormal PTH elevation.

Renal insufficiency is clearly a contributing factor to PPNCHPPT. Glomerular filtration rates below 70 mL/min already give rise to an increase in PTH values, and supranormal PTH levels are reached below 60 mL/min, albeit without a substantial effect on calcium until the glomerular filtration rate is below 20 mL/min.4,6,12,13 The same is not true for hypercalciuria, as its effect on PPNCHPPT is not fully understood. The first isolated cases were reported in the 1970s and 1980s, in which hypercalciuria was associated with HPPT recurrence.16 In 2005, Farooki et al.20 insisted that hypercalciuria should be regarded as a cause of PPNCHPPT. Idiopathic hypercalciuria is a metabolic abnormality that may be accompanied by urinary bladder stones and decreased bone mineral density, although characteristically patients do not have supranormal PTH values, unlike those with hypercalciuria secondary to HPPT.23,26–28 This does not tally with other studies in which elevated PTH values were attributed to some patients with idiopathic hypercalciuria,29,30 and has led current reviews to continue to consider idiopathic hypercalciuria as a cause of supranormal PTH levels.1–3 In patients with PPNCHPPT and hypercalciuria, it should be considered that hypercalciuria may be secondary to PPNCHPPT or that there are two concomitant diseases, idiopathic hypercalciuria and another factor leading to elevated PTH levels. In our series, there was one recognised case of hypercalciuria in the group with PPNCHPPT, associated with vitamin D deficiency, treated preoperatively, but not postoperatively, with vitamin D supplementation. The patient's calcifediol levels failed to normalise and supranormal PTH levels persisted during follow-up. In this case we were unable to establish the role of hypercalciuria in PTH elevation.

A change in the calcium regulation point on PTH secretion has been ruled out in two studies with different methodologies after evaluating this possible aetiopathogenesis of PPNCHPPT.6,10 A lower percentage of early postoperative PTH decrease in patients with PPNCHPPT suggests an increase in the calcium-mediated PTH secretion regulation point,6 although this was also not observed in our patients, hence it seems reasonable to rule out this phenomenon as a cause of PPNCHPPT.

Peripheral resistance to the action of PTH has also been considered as a possible aetiopathogenic mechanism of PPNCHPPT.1,2 Resistance to the renal effect of PTH was initially reported in patients with HPPT secondary to vitamin D deficiency due to a diminished response in the generation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate after the exogenous administration of PTH, which normalised after treatment with vitamin D.17 In another study, six weeks after parathyroidectomy, after an infusion of PTH, the rise in calcium and decrease in phosphataemia were seen to be lower in patients with PPNCHPPT than in those with normal PTH, which was interpreted as a reduction in peripheral sensitivity to PTH.18 This phenomenon of peripheral resistance to PTH could be caused by lower vitamin D levels and/or more severe preoperative HPPT, which would lead to a down-regulation in the number of PTH receptors.10,18 In the study by Dhillon et al.,19 the lower 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D/PTH ratio found in patients with PPNCHPPT was interpreted as renal resistance to PTH, endorsed by the group of Yamashita et al.,12 due to a higher preoperative PTH/renal cyclic adenosine monophosphate ratio, stressing that this resistance to PTH was greater in cases with renal insufficiency and vitamin D deficiency. Studies on peripheral resistance to the action of PTH are scant and do not provide a uniform and validated formula that can be applied routinely in clinical practice. They are based on response to the administration of PTH or on the ratio of PTH to a metabolite produced as a consequence of its action. Our study evaluated the preoperative PTH/AAC ratio, since AAC is a metabolite directly related to the action of PTH, and in the preoperative period it is not influenced by the dynamic changes of the postoperative period. This PTH/AAC ratio, described for the first time here, was significantly higher in patients with PPNCHPPT, indicating that a higher PTH level does not result in proportionally higher calcium, which could be consistent with peripheral resistance to the action of PTH. This could be related to more severe cases of HPPT given the higher preoperative PTH levels, to vitamin D deficiency and to the greater proportion of patients with chronic renal failure in this group of PPNCHPPT patients.

Regarding the predictive markers of PPNCHPPT, most authors report a higher preoperative PTH concentration5,6,10–15,19 and a larger resected adenoma size.10,13,18 Elevated osteocalcin,10 lower bone mineral content, lower vitamin D levels and lower postoperative calcium5,6,11–13,15 have also been described as predictive markers for PPNCHPPT. Older patient age has been found to be a predictor of PPNCHPPT in relation to a higher associated vitamin D deficiency.6,10,13–15,21 In our study, the age of the cases with PPNCHPPT was significantly lower, contrary to expectations, possibly because other factors such as a higher preoperative PTH level had an impact on this group. Similarly, the higher bone mineral density values in these patients may be related to their younger age. Furthermore, PTH values, and particularly the PTH/AAC ratio in the early postoperative period, at one week after surgery, have made it possible to obtain previously undescribed cut-off points with high sensitivity and specificity for predicting PPNCHPPT. The slight elevation of AAC one month after surgery may have been due to the significant increase in PTH over the previous weeks.

A large proportion of patients with PPNCHPPT achieve normalisation of PTH during follow-up, as was the case in 50% of our patients. In other series, normalised PTH is reported in 30%–60% of patients at a follow-up time of 1–1.5 years.1,2,6–11,13,19,25 This normalisation of PTH could be a result of a spontaneous postoperative or treatment-induced correction of vitamin D deficiency and the deficit in intestinal calcium intake or absorption, as well as the resolution of bone remineralisation.8,10,11,25 Our series suffers from a low percentage of patients treated with calcium salts, which could have worsened their outcome. Occasionally, patients with PPNCHPPT progress to recurrent HPPT by developing hypercalcaemia, which occurs in 0%–4.8% at a 10-year follow-up7,8,11,13,15,19 and up to 5.4% if patients with multiglandular disease are included.14,24 Patients with a recurrence of HPPT have been associated with increased preoperative HPPT involvement, increased preoperative calcium and impaired renal function13 and increased postoperative calcium.14 The recurrence rates described have not been uniformly higher than those found in patients without PPNCHPPT, as was the case in our study.2,3,15

There is currently no consensus on the management of patients with PPNCHPPT. Regardless, it would seem advisable to ensure that they have appropriate vitamin D levels and sufficient dietary intake of calcium.3 Treatment based on calcium salts with or without vitamin D supplementation has resulted in increased bone mineral density and significant decreases and normalisation of postoperative PTH.7,12,21 In some centres, it has been routinely recommended for all patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for HPPT,1 whereas in others only for patients with PPNCHPPT.2 Postoperative vitamin D treatment is also known to reduce the incidence of PPNCHPPT9 and has been recommended for patients with PPNCHPPT based on renal resistance to the action of PTH in vitamin D-deficient cases.12 In our series, almost all the patients had received vitamin D supplementation, but in the PPNCHPPT group this was insufficient to maintain adequate calcifediol levels for six months post-parathyroidectomy. In contrast, few, and significantly fewer patients in the PPNCHPPT group, were given calcium salts. Preoperative treatment with bisphosphonates in patients with osteoporosis and HPPT has a clear beneficial effect, improving bone mineral density by significantly decreasing or normalising bone turnover.22 This effect may also have been significant in the group of patients without PPNCHPPT, as they had received bisphosphonates more frequently. The utility of bisphosphonates for less expressive cases of bone remineralisation, without osteoporosis, remains to be studied.

This study has certain limitations. Its retrospective nature led to some data being missed in the recording of variables, which was taken into account in each statistical analysis carried out. The sample size was relatively small, moderate compared to other studies,6,8–10,12,18,19,25 and may have resulted in lower statistical power for detecting significant differences. The mean postoperative follow-up period of PPNCHPPT cases was limited to about 2.5 years; a longer period might have different outcomes. The definition of bone remineralisation syndrome is imprecise, as there are no diagnostic criteria for its severity, whereby less severe forms than those reported here may have gone undetected. We were unable to assess inadequate calcium intake or absorption as a cause of PPNCHPPT, as other retrospective studies have done. Bisphosphonate treatment in the group of patients without PPNCHPPT may have slightly increased PTH values and reduced calcium values, although this effect did not prevent the recognition of higher PTH and PTH/AAC ratio values in the PPNCHPPT group.

In conclusion, PPNCHPPT is a complex and common clinical situation. This is the first study in Spain to demonstrate an average prevalence of patients with PPNCHPPT and recognises that in most cases it is related to vitamin D deficiency and possible peripheral resistance to the action of PTH, taking into account that a precise and operational definition and stratification of post-parathyroidectomy bone remineralisation is not available. Continuing to consider hypercalciuria and a change in the calcium-mediated PTH secretion regulation point as causes of PPNCHPPT is also questionable. We describe the PTH/AAC ratio and PTH one week after surgery as accurate predictive markers of PPNCHPPT. Half of the cases with PPNCHPPT evolve to normal PTH and the recurrence rate of HPPT was not higher in this group of patients. Preoperative treatment with bisphosphonates in cases of osteoporosis and postoperative vitamin D supplementation may minimise the frequency of PPNCHPPT, although we would draw attention to the scant use of postoperative treatment with calcium salts.

AuthorsEach author has contributed materially to the research and preparation of the article. Specifically:

- -

Luis García Pascual: study conception and design, data acquisition and analysis, interpretation of results, writing of the draft and approval of the final version.

- -

Andreu Simó-Servat, Carlos Puig-Jové, Lluís García-González: study conception and design, interpretation of results, critical review and approval of the final version.

- -

Protection of people and animals. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

- -

Data confidentiality. The authors declare that they have adhered to their workplace protocols on the publication of patient data.

This study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.