The prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide over the past decades. Obesity is associated with multiple comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes, that generates a great impact on health and economy. Weight loss in these patients leads to glycemic control so it is a target to achieve. Lifestyle changes are not effective enough and recently other treatments have been developed such as bariatric/metabolic surgery, as well as drugs for type 2 diabetes and antiobesity drugs. The aim of this review is to compare the results in weight reduction and glycemic control of the different kinds of drugs with bariatric/metabolic surgery's results in type 2 diabetes.

La prevalencia de la obesidad se ha incrementado mundialmente en las últimas décadas. La obesidad se asocia a múltiples comorbilidades, como la diabetes tipo 2, que generan un gran impacto en la salud y en la economía. La pérdida de peso en este colectivo favorece el control glucémico, por lo que es uno objetivo a lograr. Los cambios en el estilo de vida son poco efectivos por sí solos, y en los últimos años se han desarrollado otras opciones terapéuticas como la cirugía bariátrica/metabólica, así como fármacos para la diabetes tipo 2 y fármacos para reducir peso en la obesidad. El objetivo de la revisión es la comparación de los resultados en reducción de peso y control glucémico de los distintos tipos de fármacos con los resultados de la cirugía bariátrica/metabólica en diabetes tipo 2.

Excess weight is usually classified based on body mass index (BMI), but potential comorbidities should also be considered as prognostic factors.1 In some people, overweight (BMI≥25kg/m2) and obesity (BMI≥30kg/m2) have a negative impact because they are associated to psychological changes, functional impairment, comorbidities such as type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), cardiovascular disease,2 and greater mortality.1,3 Even people in whom they apparently have little effect (“metabolically healthy”) have a greater long-term risk of cardiovascular events and greater mortality as compared to the population with normal BMI.4

According to the WHO, in 2016 more than 1.9 billion adults had overweight, and 650 million of these were obese.5 Increased incidence of obesity and its severity result in higher prevalence of T2DM and promote occurrence of complications in this group. Patients with T2DM achieve a lower weight reduction than people with no diabetes, which is partly due to some types of hypoglycemic treatments such as insulin therapy. Dietary treatment and lifestyle changes are essential mainstays in management of obesity and T2DM (weight loss ≥3% in patients with T2DM improve blood glucose control),6 but results are often poor and difficult to maintain over time.7

Use of different drugs8 to treat obesity that contribute to improve T2DM control and promote weight loss has recently been approved. There are also drugs to treat T2DM that have a beneficial effect on weight, such as SGLT-2 inhibitors and GLP-1 receptor agonists. Bariatric surgery has been shown to be effective for weight loss and for resolving comorbidities, especially T2DM.9–13

This review was intended to analyze the effect on metabolic control in T2DM of drug treatment of obesity, and the effect on weight loss of some drugs used in the treatment of T2DM. In addition, the results were compared to those achieved with bariatric/metabolic surgery.

Drugs to treat T2DM that promote weight lossMetformin continues to be the first therapeutic option in obese patients with T2DM because, in addition to controlling hyperglycemia, its use has been associated to a decreased intake and small weight losses in patients with T2DM,14 adults with prediabetes,15 and children with overweight and hyperinsulinemia.16

There has been recently a great change in treatment of T2DM with the advent of new hypoglycemic drugs that have a favorable impact in metabolic control and promote significant weight losses.

Selective sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i)These drugs act by inhibiting sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 in the kidney and blocking glucose reabsorption in proximal tubule, both insulin-independent mechanisms. SGLT2i induce renal loss of approximately 75g of glucose (∼300kcal),17 promoting a negative energy balance. A 2013 meta-analysis reported decreases in HbA1C levels by approximately 0.66%18 with these drugs. More recent studies have reported decreases in HbA1C levels ranging from 0.45% and 1.03% and weight losses ranging from 2.2kg and 3.6kg from baseline weight.19

SGLT-2i may be used in any stage of T2DM combined with most antidiabetic drugs, and they may even preserve pancreatic beta cell function. The most relevant adverse effects reported with use of SGLT-2i include genitourinary infections, volume depletion and diabetic ketoacidosis. The latter is less common, but more relevant because of its severity.

The EMPA-REG20 and CANVAS21 studies have shown decreases in cardiovascular and renal events in patients with T2DM treated with empagliflozin and canagliflozin respectively.

Glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RA)GLP-1 RAs enhance glucose-mediated insulin secretion, stimulate insulin secretion by beta cells, suppress glucagon secretion by pancreatic alpha cells, and slow gastric emptying. They thus achieve long-term reductions in HbA1C levels ranging from 0.4% and 1.7% depending on studies.22 GLP-1 RA also cause satiety and decreased appetite and Food intake, and act on the central nervous system, which results in weight losses ranging from 0.9kg and 5.3kg.23,24 They also have effects on energy expenditure and thermogenesis.25 In a recent systematic review comparing different GLP-1 RA (albiglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide twice daily and weekly, and liraglutide), no significant differences were seen in weight loss, but dulaglutide and liraglutide were superior in blood glucose control as compared to exenatide twice daily.26 Semaglutide has been shown to be superior to exenatide weekly in blood glucose control and weight reduction (−1.5% vs. −0.9% in HbA1C and −5.6kg vs. −1.9kg in weight).27

Table 1 shows the adverse effects associated to their use.

Drugs for weight loss in obesity Mechanism of action, daily dose and side effects.

| Drug | Mechanism of action | Daily dose | Mean weight lost in T2DM with the drug vs. placebo in one yeara | Mean HbA1C reduction (%)b | Side effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Orlistat | Inhibition of gastric and pancreatic lipases: fat malabsorption | 120mg/3 times daily, oral | 4.5/2.1kg | 3.16 | Steatorrhea Fecal incontinence Decreased lipid-soluble vitamin absorption |

| Lorcaserin | Selective serotonin receptor (5-HT2C) agonist | 10mg/twice daily, oral | 5/1.6kg | 0.9 | Hypoglycemia Headache Back pain Nausea Dry mouth Fatigue Dizziness Constipation |

| Liraglutide | GLP-1 agonist | 3mg/day, subcutaneous | 6.4/2.2kg | 1.3 | Nausea Vomiting Diarrhea Constipation Gallstones Pancreatitis Hypoglycemia Abdominal pain |

| Phenterminec | Adrenergic agonist | 8–37.5mg/day, oral | 6/1.5kg | 0.1d | Dry mouth Constipation Headache Insomnia Upper respiratory tract infection Nasopharyngitis Paresthesia Blurred vision and dizziness |

| Phentermine/topiramate | Sympathomimetic action on central nervous system and anticonvulsant | 3.75/23mg 7/46mg 11.25/69mg Once daily, oral | 6.8%–8.8%/1.9% | 0.4–1.6 | Paresthesia Dysgeusia Dizziness Constipation Insomnia Dry mouth Increased heart rate |

| Naltrexone/bupropion | Inhibition of dopamine and norepinephrine uptake Opioid antagonist | 16/180mg/twice daily, oral | 5.2/1.8kg (NR) | 0.6 | Nausea Vomiting Constipation Headache Dizziness Increased blood pressure and heart rate Bupropion: increased risk of suicide |

NR: not reported.

The cardiovascular benefits seen are attributed to the extrapancreatic pleiotropic effects of GLP-1 RA on the cardiovascular system and their favorable impact on cardiovascular risk factors other than glucose levels, including weight, blood pressure, and lipids. GLP-1 receptors are distributed in different places in the body, including endothelial cells, cardiac cells, and smooth muscle cells in the vessels. The mechanism of action is based on activation of the enzyme nitric oxide synthase and on inhibition of other endothelial factors, decreasing endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Treatment with liraglutide or exenatide has been associated to decreases in blood pressure and cardiovascular risk biomarkers such as plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 and C-reactive protein. GLP-1 RAs have also been shown to have beneficial effects on lipid profile, decreasing free fatty acid, triglyceride, and LDL cholesterol levels.28

The LEADER29 and SUSTAIN 630 studies have shown decreases in cardiovascular and renal events in patients with T2DM treated with liraglutide and semaglutide. Liraglutide also decreases visceral fat, specifically liver steatosis.31

Drug combinationsThe combination of selective SGLT2i and GLP-1 RA is an attractive therapeutic option for patients with T2DM and obesity because the mechanisms of action of these drugs are complementary. The DURATION 8 study showed that the combination of dapagliflozin once daily and exenatide weekly decreased weight by 3.4kg and HbA1C level by 2% after 28 weeks of treatment.32 The AWARD-10 study, recently published online, reported a 1.34% decrease in HbA1C in patients with T2DM not controlled on selective SGLT2i when combined with dulaglutide 1.5mg weekly after 24 weeks of treatment.33 Other possible drug combinations are possible: thus, in a post hoc of the CANVAS study, treatment with canagliflozin 300mg daily together with GLP-1 RA (exenatide or liraglutide) caused additional decreases in weight and systolic blood pressure.34

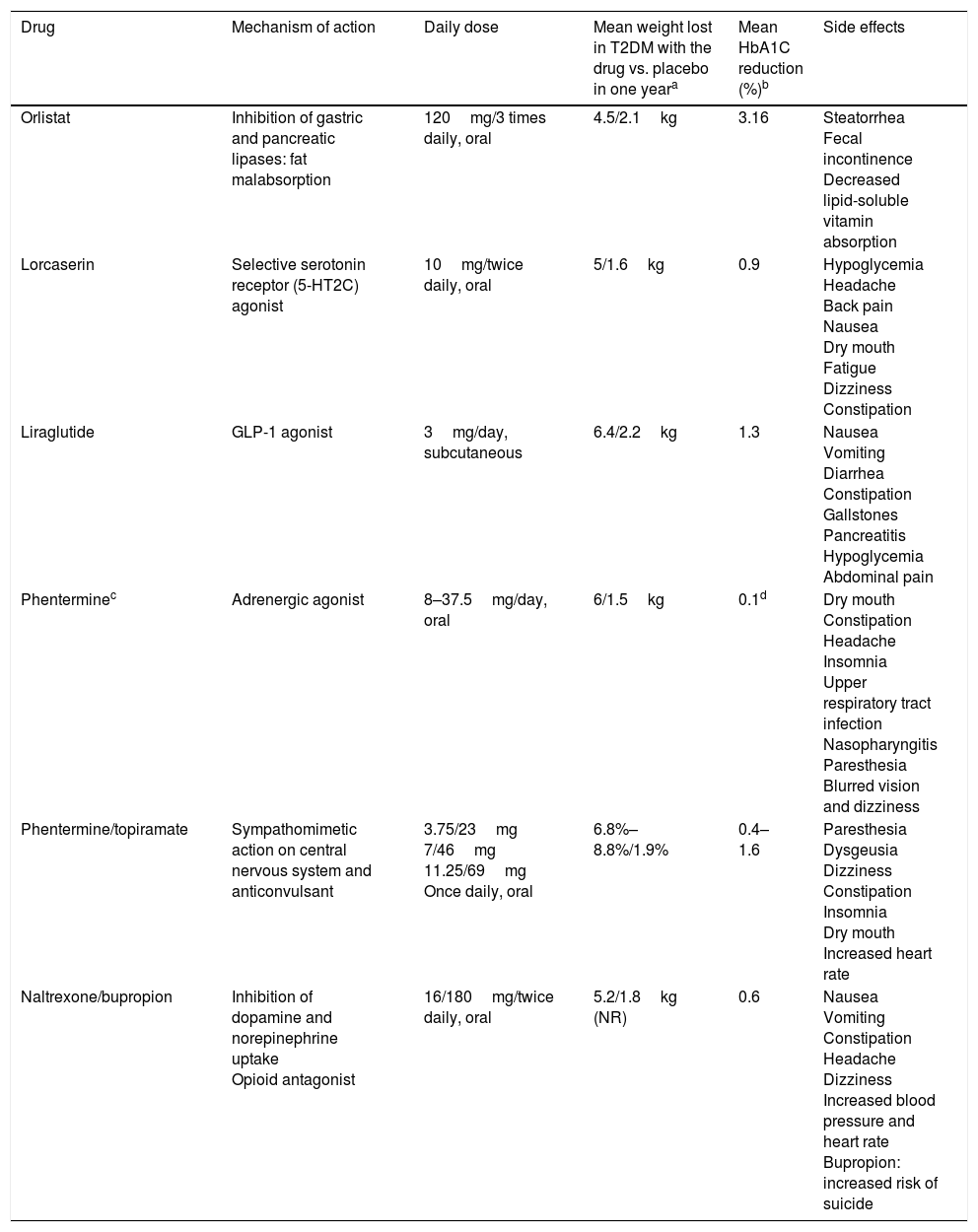

Drugs for weight loss in obesity and their use in patients with T2DMAlthough some drugs approved for weight loss have been withdrawn because of their significant adverse effects,35 other new drugs have been approved. In Europe, lorcaserin, phentermine/topiramate, and phentermine monotherapy are not yet available. These drugs are indicated when BMI is ≥30kg/m2 or ≥27kg/m2 with comorbidities such as dyslipidemia, high blood pressure, sleep obstructive apnea, or T2DM.36 They should always be offered together with lifestyle changes. Table 1 includes the drugs approved for obesity in the United States and their mechanism of action, daily dose, effects on weight and blood glucose control, and main side effects.

OrlistatIn a meta-analysis of 12 randomized clinical trials in obese patients with T2DM, administration of orlistat decreased weight by 4.25kg and HbA1C level by 3.16%. In the group treated with placebo, weight loss was only 2.1kg and HbA1C decreased 2.52% only.37

Treatment with orlistat has been shown to decrease by approximately 50% the risk of progression to T2DM in patients with prediabetes, but does not change the degree of progression to T2DM when basal blood glucose is normal. Orlistat also has positive effects on cardiovascular risk factors and causes significantly greater decreases in blood pressure, waist circumference, and LDL cholesterol levels as compared to placebo.38 Orlistat has been shown to decrease coronary risk in patients with metabolic syndrome.39

Prescription of orlistat would be most appropriate in patients with constipation and/or hypercholesterolemia that limit dietary fat intake, and use of the drug should be avoided in patients with gastrointestinal disease with episodes of diarrhea and in pregnant women.40

LorcaserinThe BLOOM-DM showed that patients treated with lorcaserin as compared to placebo lose more weight (5kg vs. 1.6kg) and achieve greater HbA1C decreases (0.9% vs. 0.4%). After 52 weeks of treatment, 37% of patients lost ≥5% (responders).41 In a subsequent analysis, benefits were seen in blood glucose control in both responders and non-responders.42

Basal blood glucose levels may decrease in the first few weeks of treatment with lorcaserin. Adjustment of the dose of hypoglycemic drugs should therefore be considered in patients with controlled T2DM.43 In the BLOOM-DM study, symptomatic hypoglycemia occurred in 7.4% of patients with T2DM treated with lorcaserin at doses of 10mg twice daily, in 10.5% of those given single daily doses of lorcaserin, and in 6.3% of the placebo group.41 In a meta-analysis assessing the addition of lorcaserin to metformin, as compared to addition of other hypoglycemic drugs, no inferiority was seen in HbA1C reduction. However, risk of hypoglycemia did not differ from that of all other hypoglycemic drugs except for sulfonylureas, whose risk hypoglycemia was higher when added to metformin.44

Based on its mechanism of action, prescription of lorcaserin would be adequate in patients with great appetite and in diabetes, and would be contraindicated in patients with heart valve disease or treated with other drugs having serotonin as route of action, or in pregnant women.40

Liraglutide 3mgThe SCALE Diabetes study showed weight losses of 6.4kg using liraglutide 3mg, 5kg with doses of 1.8mg and 2.2kg with placebo. With the 3mg dose, weight losses ≥5% were seen in 54.3% of patients. Considering glycemic control HbA1C decreased 1.3% with the 3mg dose, 1.1% with 1.8mg, and 0.3% with placebo.45 A subsequent analysis showed decreased risk of T2DM in patients with obesity and prediabetes with the 3mg dose.46

Prescription of liraglutide would be most adequate in patients who report no satiety with Food and with impaired carbohydrate metabolism or cardiovascular disease. By contrast, liraglutide should be avoided in patients with history of medullary thyroid carcinoma o pancreatitis and in pregnant women.40

PhentermineA randomized study comparing phentermine, topiramate and their combination for 28 weeks showed that phentermine 15mg daily induced a mean weight loss of 6kg, as compared to 1.5kg with placebo.47 Other study showed no differences in weight loss with continuous or intermittent phentermine treatment versus placebo.48

Prescription of phentermine as monotherapy would be most adequate in young patients to decrease appetite. Prescription is approved for short time periods (three months). Phentermine is not adequate for patients with cardiovascular disease (high blood pressure, heart disease), hyperthyroidism, anxiety, insomnia, glaucoma, personal history of drug addiction or recent use of MAO inhibitors or in pregnant women.40

Phentermine/topiramateThe CONQUER study included 2487 patients with overweight, obesity, and comorbidities (15.6% with T2DM) and showed greater weight losses (8.8% vs. 1.9%) and HbA1C reductions (0.4% vs. 0.1%) in patients given this drug combination as compared to placebo after 56 weeks of treatment.49 In the extension study (SEQUEL), HbA1C reductions by up to 0.4% were seen in the group of patients with diabetes at 52 weeks of treatment.

Similar results were achieved in the OB-202/DM-230 study, where 65% of patients treated for 56 weeks with phentermine/topiramate lost ≥5% of weight (24% with placebo). In addition, the group given this drug combination showed greater weight loss (9.4kg vs. 2.7kg with placebo) and HbA1C reduction (1.6% vs. 1.2% with placebo).50 Using doses of 15mg/92mg for 108 weeks, progression to T2DM decreased in patients with prediabetes and/or metabolic syndrome.51

Phentermine/topiramate has the same indications and contraindications as phentermine monotherapy, and this treatment should be avoided in patients with nephrolithiasis.40

Naltrexone/bupropionThe COR-Diabetes study, conducted in 505 patients with T2DM, showed greater weight loss (5% vs. 1.8%) and HbA1C reduction (0.6% vs. 0.1%) in the group given this combination for 56 weeks as compared to the placebo group. Weight losses ≥5% were achieved by 44.5% of patients treated with the combination versus 18.9% of the placebo group.52

Prescription of naltrexone/bupropion would be most appropriate in patients with anxiety or food addiction behaviors and who have other addictive behaviors such as alcohol consumption or smoking and/or experience depression. The combination would not be indicated in patients with risk of seizures or treated with MAO inhibitors, high blood pressure, uncontrolled pain, abrupt benzodiazepine withdrawal, alcohol, antiepileptic drugs or barbiturates, or pregnant women.40 Bupropion may increase risk of suicide and should be avoided in patients with these characteristics.

Future drug therapiesNew drug combinations for weight loss are under study. Phentermine/lorcaserin was tested in a randomized, double-blind clinical trial in a sample of 238 obese or overweight patients with at least one comorbidity but no diabetes. A short-term improvement was seen in weight loss with no increase in serotonergic side effects.53 Canagliflozin/phentermine is another potential drug combination in the future. This treatment achieved greater weight loss and a ≥5% decrease in systolic blood pressure as compared to placebo in a Phase 2 clinical trial in a sample of 335 patients without diabetes who had obesity or overweight with high blood pressure or dyslipidemia.54 Other treatments under study include melanocortin-4 receptor agonists (which have a significant role in regulation of food intake), inhibitors of the enzyme methionine aminopeptidase 2, and intestinal peptides (peptide YY [3-36], PYY receptor agonists, and ghrelin antagonists). Hybrid drugs (with dual actions on GLP-1 and GIP receptors, GLP-1 and GLP-2 receptors, or GLP-1 and glucagon receptors) and triple-acting agonist drugs are also being developed.55

Bariatric/metabolic surgeryThe most recent guidelines recommend as goal in the treatment of obesity the loss of 5%–10% of baseline weight over six months,36 which is difficult to achieve with diet and lifestyle changes, even when drugs are also used.7 Surgery is more effective for weight loss (15%–30%)56 and for long-term reduction of mortality and comorbidities. This has resulted in a significant increase in the number of bariatric/metabolic surgeries performed in recent years.

The most commonly used surgical procedures include Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) (48% of procedures worldwide) and vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG), (42%), followed by the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (LAGB) (8%) and biliopancreatic diversion (BPD) (2%).57 A meta-analysis of 136 studies examined the results of 22,000 surgical procedures (most of them in the short term) and found mean weight losses of 61.6% with RYGB, 68.2% with VSG, 70.1% with BPD, and 47.5% with LAGB.58

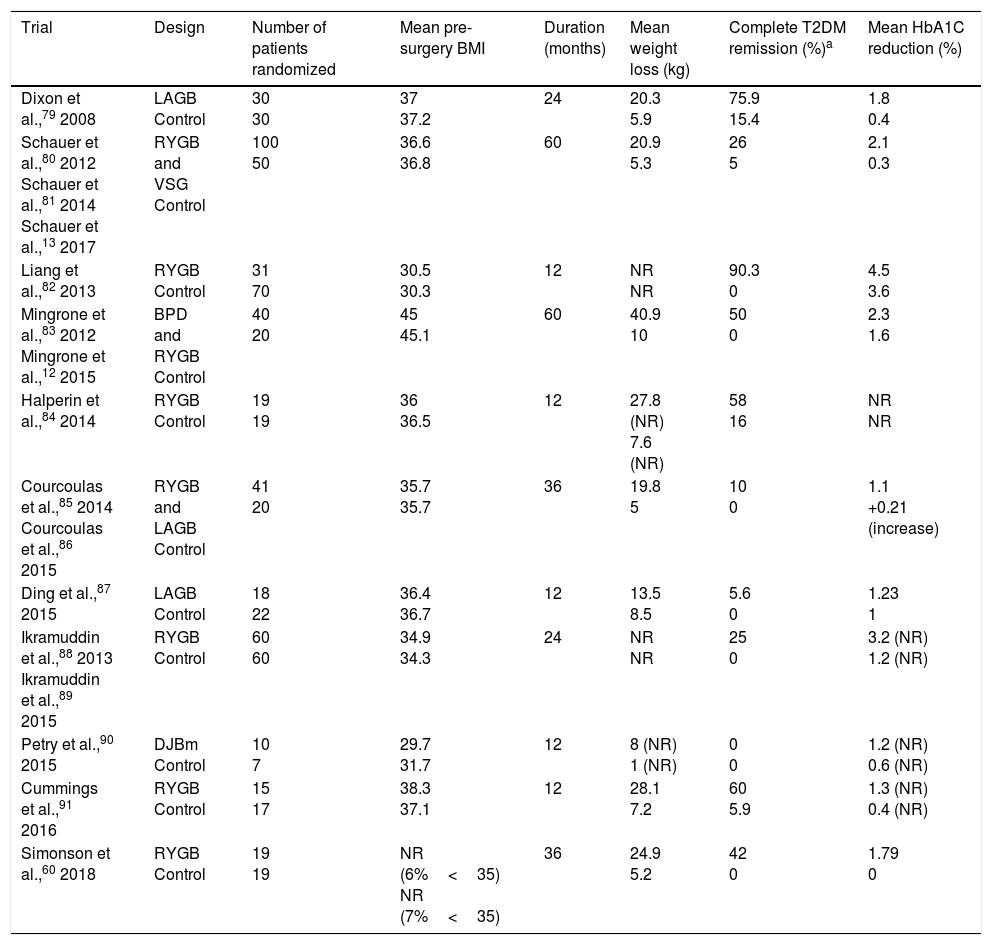

In addition to weight loss, bariatric/metabolic has been shown to achieve resolution of comorbidities such as T2DM and other cardiovascular risk factors (high blood pressure and dyslipidemia) in observational studies such as the Swedish Obese Study9 and in clinical trials (Table 2). Although T2DM remission is seen in 30%–63% of cases, the condition may recur in 35%-50% of patients. Mean HbA1C reduction is 2% after surgery, as compared to 0.5% with standard medical treatment.59 Simonson et al.60 reported a recent randomized study where HbA1C level decreased by 1.9% in patients with T2DM treated with bariatric surgery, while no changes were seen in the group on intensive medical treatment. Despite these beneficial effects, few patients with T2DM (<1%) currently undergo surgery.36

Randomized controlled clinical trials in bariatric/metabolic surgery in patients with T2DM.

| Trial | Design | Number of patients randomized | Mean pre-surgery BMI | Duration (months) | Mean weight loss (kg) | Complete T2DM remission (%)a | Mean HbA1C reduction (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dixon et al.,79 2008 | LAGB Control | 30 30 | 37 37.2 | 24 | 20.3 5.9 | 75.9 15.4 | 1.8 0.4 |

| Schauer et al.,80 2012 Schauer et al.,81 2014 Schauer et al.,13 2017 | RYGB and VSG Control | 100 50 | 36.6 36.8 | 60 | 20.9 5.3 | 26 5 | 2.1 0.3 |

| Liang et al.,82 2013 | RYGB Control | 31 70 | 30.5 30.3 | 12 | NR NR | 90.3 0 | 4.5 3.6 |

| Mingrone et al.,83 2012 Mingrone et al.,12 2015 | BPD and RYGB Control | 40 20 | 45 45.1 | 60 | 40.9 10 | 50 0 | 2.3 1.6 |

| Halperin et al.,84 2014 | RYGB Control | 19 19 | 36 36.5 | 12 | 27.8 (NR) 7.6 (NR) | 58 16 | NR NR |

| Courcoulas et al.,85 2014 Courcoulas et al.,86 2015 | RYGB and LAGB Control | 41 20 | 35.7 35.7 | 36 | 19.8 5 | 10 0 | 1.1 +0.21 (increase) |

| Ding et al.,87 2015 | LAGB Control | 18 22 | 36.4 36.7 | 12 | 13.5 8.5 | 5.6 0 | 1.23 1 |

| Ikramuddin et al.,88 2013 Ikramuddin et al.,89 2015 | RYGB Control | 60 60 | 34.9 34.3 | 24 | NR NR | 25 0 | 3.2 (NR) 1.2 (NR) |

| Petry et al.,90 2015 | DJBm Control | 10 7 | 29.7 31.7 | 12 | 8 (NR) 1 (NR) | 0 0 | 1.2 (NR) 0.6 (NR) |

| Cummings et al.,91 2016 | RYGB Control | 15 17 | 38.3 37.1 | 12 | 28.1 7.2 | 60 5.9 | 1.3 (NR) 0.4 (NR) |

| Simonson et al.,60 2018 | RYGB Control | 19 19 | NR (6%<35) NR (7%<35) | 36 | 24.9 5.2 | 42 0 | 1.79 0 |

BPD: biliopancreatic diversion; DJBm: duodenal-jejunal bypass surgery with minimal gastric resection; LAGB: laparoscopic adjustable gastric band; NR: not reported; RYGB: Roux-en-Y gastric bypass; VSG: vertical sleeve gastrectomy.

The order of choice of the procedure based on effectiveness to improve T2DM and weight loss would be BPD>RYGB>VSG>LAGB. The reverse order would be based on safety of the procedure.57 Although biliopancreatic diversion is theoretically the most effective procedure, it is the least used procedure because of its side effects derived from malabsorption. RYGB is therefore considered the procedure of choice for patients with T2DM, although VSG is more frequently used in many countries. In Spain, there has been an overall increase in use of VSG in the past 15 years.61

All surgical procedures improve blood glucose control because of weight loss; the most marked results are seen however with RYGB and VSG, and occur before weight loss.62,63 A possible explanation would be the recovery of pancreatic beta cell function after these surgical procedures. Mechanisms other than weight loss have been implicated in T2DM improvement or resolution64–67: bile acid changes, changes in intestinal microbioma and in nutrient detection mechanism in the gastrointestinal tract that modulate insulin sensitivity, increased postprandial secretion of intestinal hormones (GLP-1), exclusion of nutrients from the proximal area of duodenum and small bowel, and downregulation of anti-incretin factors not yet identified. All of these may contribute to the “antidiabetic” effect of metabolic surgery. Any patients with T2DM, regardless of their BMI, may benefit from the antidiabetic mechanisms not related to weight loss.68 The American Diabetes Association therefore recommended in 2018 that metabolic surgery is considered in patients with BMI 30kg/m2 or higher (27.5kg/m2 in Asians) and uncontrolled T2DM,69 in addition to the classical indications in patients with BMI≥35kg/m2 (32.5kg/m2 in Asians) and uncontrolled hyperglycemia or BMI≥40kg/m2 (37.5kg/m2 in Asians). Hypoglycemic treatment of patients with diabetes should be adjusted after bariatric surgery because reduction or even discontinuation of pre-surgery treatment is required in most cases due to improved blood glucose control.70

Despite their good metabolic and weight results, the different surgical procedures are not free from complications.71 There are high repeat surgery rates after LAGB due to erosion, slippage and obstruction, and surgery may cause progressive esophageal dilation. VSG has, as compared to RYGB, greater risk of postoperative gastroesophageal reflux and long-term obstructive problems. Complications associated to RYGB include nausea and vomiting (even dehydration), dumping síndrome and, less commonly, pneumonia, surgical wound infection, cardiac arrhythmia, and cholelithiasis. In the long term, intestinal obstruction, marginal ulcer and hernia may occur. There are life-threatening complications such as shock secondary to postoperative bleeding, sepsis from anastomotic dehiscence or cardiopulmonary disease. Thromboembolic disease rate is approximately 0.34%.56 An additional disadvantage of surgery is long-term weight recovery (2%–18% of patients, depending on the procedure, return to their baseline weight),72 as well as secondary recurrence of the comorbidities associated to obesity, such as T2DM.

Nutritional monitoring is required after bariatric surgery, especially after malabsorptive procedures. Blood tests including nutritional parameters should be performed during the first year after surgery every three months, during the second year every six months and yearly thereafter. Long-term supplementation with vitamins and minerals at higher or lower doses depending on the type of surgery performed is recommended.73 To prevent deficiency of micronutrients, multivitamin supplements or separate supplementation with thiamine 12mg/day, vitamin B12 (350–500mcg/day), folic acid (400–800mcg/day), and iron (at least 18mg/day and 45–60mg/day for women of childbearing age and after malabsorptive surgery) are required. Calcium (1200–1500mg/day for RYGB, VSG and LAGB, and 1800–2400mg/day for BPD) and vitamin D3 (3000U/day until blood vitamin D levels >30ng/mL are achieved), vitamin A (5000–10,000IU/day), vitamin K (90–120mcg/day), vitamin E (15mg/day), zinc (8–22mg/day), and copper (1–2mg/day) should also be provided.74 Thiamine deficiency requires special care, because it may cause Wernicke encephalopathy.

Future surgical proceduresInnovative surgical procedures aimed at achieving the “antidiabetic” benefit of surgery not related to weight loss have been developed in recent years. Metabolic control and small weight losses are achieved. Such procedures include:

- 1.

Ileal transposition and its variants (isolated ileal transposition, combined with gastric sleeve or with gastric sleeve and duodenal exclusion)75: the mechanism of ileal transposition is based on interposition of an ileal segment into the proximal jejunum to promote early passage of food across the ileum. This results in increased GLP-1 levels that enhance insulin secretion and increase sensation of satiety.

- 2.

Duodenal-jejunal bypass with or without gastric sleeve and EndoBarrier: one of the theories to explain its effect is that change in direction of food after surgery may cause decreases in the endocrine factors present in duodenum and jejunum that promote insulin resistance, leading to a sustained metabolic response.75 The EndoBarrier consists of implantation of a device to avoid contact of Food with the wall of the proximal bowel.76 Basal blood glucose levels decrease from the first week after insertion and reduce HbA1C by 1.2%–2.3%. The main limitation of this procedure is that the polymer must be removed at 6–12 months, or earlier if complication occur (abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, bleeding).77

- 3.

Other procedures: Single anastomosis duodeno-ileostomy with sleeve gastrectomy and single anastomosis duodeno-jejunostomy are effective procedures for resolution of diabetes, but with frequent nutritional complications similar to those of biliopancreatic diversion.75

The pathophysiology of obesity is complex, and devising an effective treatment is difficult. Bariatric/metabolic surgery was initially indicated in severe obesity, but it has recently been shown to be equally effective for resolution of comorbidities in less severe obesity. Drugs are less potent in terms of weight loss and glucose control, but are free from the risks of surgery and do not require concomitant long-term vitamin supplementation. Prescription should be individualized and, if not effective or if adverse effects occur, medication should be discontinued and switched to other drugs with other mechanisms of action.

The combination of surgery and drugs is an attractive therapeutic option. Drugs may be used in patients who experience inadequate weight losses after surgery or new weight gain over time,78 but additional studies are needed to generalize their use in this population.

New surgical techniques and procedures will be available in the future, as well as new drugs for weight loss that are currently under research.

Conflicts of interestThe authors Rosa Cámara Gómez and Juan Francisco Merino Torres have participated in papers on drugs for weight reduction in obesity. Matilde Rubio-Almanza states that she has no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Rubio-Almanza M, Cámara-Gómez R, Merino-Torres JF. Obesidad y diabetes mellitus tipo 2: también unidas en opciones terapéuticas. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:140–149.