Prader–Willi syndrome is a genetic disorder caused by chromosomal changes in segment 15q11-q13 including cognitive, mental, and behavioral symptoms, as well as a specific physical phenotype. Both the most common psychopathological changes (intellectual disability, obsessions, impulsivity, autism spectrum disorders, self-injuries) and the main psychiatric comorbidities (affective disorders, psychosis, obsessive–compulsive disorder, autism spectrum disorder) are characterized by a great heterogeneity, which warrants the need for better identification of their frequency and clinical signs. In addition to its effects on body composition and hypotony, growth hormone has been shown to be useful for regulating patient behavior, and psychoactive drugs are also an option. Other alternatives have shown promising results in experimental trials. Adequate understanding of the psychopathology associated to Prader–Willi syndrome would allow for improving clinical approach, symptom identification, detection of comorbidities, and administration of more effective treatments, leading to better clinical outcomes.

El síndrome de Prader-Willi es un trastorno genético causado por alteraciones cromosómicas en el segmento 15q11-q13 que incluye sintomatología cognitiva, mental y conductual, así como un fenotipo somático específico. Tanto las alteraciones psicopatológicas más comunes (discapacidad intelectual, obsesiones, impulsividad, comportamientos de tipo autista, autolesiones) como las comorbilidades principales (cuadros afectivos, psicosis, trastorno obsesivo-compulsivo, trastorno del espectro autista) se caracterizan por una gran heterogeneidad, lo que justifica la necesidad de una mayor caracterización de su frecuencia y modo de presentación. Además de sus efectos sobre la composición corporal y la hipotonía, la hormona del crecimiento ha demostrado utilidad en el control conductual, así como algunos psicofármacos. También se han descrito alternativas a nivel experimental que están mostrando resultados alentadores. Un adecuado conocimiento de la psicopatología asociada a este síndrome permitiría mejorar el abordaje clínico, la identificación de los síntomas, la detección de comorbilidades y la instauración de un tratamiento más efectivo.

Prader–Willi syndrome (PWS) is a neurodevelopmental genetic disorder first described in 1956 and characterized by a specific physical and mental phenotype. The estimated prevalence is between 1:10,000 and 1:30,000, and the syndrome is caused by a lack of expression of genes of paternal origin in segment 15q11-q13. The chromosomal alteration responsible for PWS conditions the so-called “genetic subtype”, which may correspond to paternal microdeletion (70–75% of cases), maternal disomy (20–25%), imprint defect (1–3%) or chromosomal translocations (<1%).1

The physical manifestations of PWS include short stature, kyphoscoliosis, hypopigmentation, genital hypoplasia due to hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, small hands and feet, a narrow bifrontal diameter, an inverted U-shaped mouth, and ocular abnormalities (myopia, strabismus or almond-shaped palpebral fissures). Decreased fetal movements during pregnancy, hypotonia with suction difficulties in the perinatal stage and childhood lethargy, which improves with age, have also been seen. Exaggerated hyperphagia and a lack of satiety are also very characteristic, resulting in significant weight gain that has been associated with multiple comorbidities: high blood pressure, lipid metabolism disorders, diabetes, sleep apnea, etc. These complications represent the main cause of mortality in this patient population.2

Apart from the somatic repercussions of the disease, mental and behavioral symptoms associated with PWS have also been reported. The present review offers an update on our knowledge of the syndrome, focusing on its clinical characteristics and the comorbid psychiatric diagnoses. The treatment particularities of the syndrome are also reviewed.

Comprehensive management of this complex disease requires a multidisciplinary approach involving not only the healthcare setting, but also the social, community and educational services. Understanding the psychopathological changes associated with PWS is essential for the clinical management of these patients, since centers specializing in this condition are not always available. The endocrinologist plays a key role in this process, because in most cases the patients are mainly seen in the endocrinology clinic once the diagnosis has been confirmed.

Physiopathological mechanismIn recent years there have been numerous studies seeking to establish a neuroanatomical basis for the psychopathological features of genetic diseases. However, few studies specifically addressing PWS are available.

Positron emission tomography (PET) has revealed temporoparietal and limbic system hypoperfusion, as well as alterations in carbohydrate metabolism in multiple brain areas.3 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in turn has made it possible to quantify a decrease in gray matter in the hippocampus and frontal and temporal lobes; a decrease in white matter in the frontal and temporal lobes, brainstem and cerebellum; and abnormalities in the connection of cortical areas and basal ganglia, mainly related to the hypothalamus.4 Other characteristic findings have been polymicrogyria in certain areas, such as in the Sylvian fissure, and GABA neurotransmitter alterations.

All these observations suggest alterations in neuronal migration and in the cerebral fold-forming phase as the potential underlying etiopathogenic mechanism. Such variations in turn could be conditioned to alterations at the chromosomal level: structural differences depending on the genetic subtype (paternal microdeletion or maternal disomy) have been reported.5

The ultimate consequence of these processes is a reduction in cortical complexity, which would at least partially account for the psychopathological alterations associated with PWS. The neuroendocrine deficits most closely associated with the somatic clinical signs (hypothalamic dysfunction, growth hormone and gonadotropin hyposecretion, among others) could also play a role, though their mental impact has not been evaluated to date.

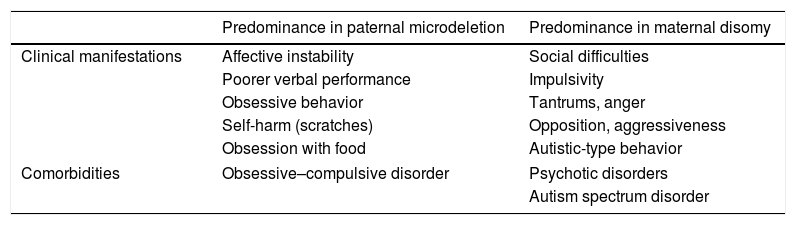

Clinical manifestationsIn determining structural differences, the genetic subtype involved also leads to variations in the clinical characteristics of PWS. This has been widely documented in relation to the two main genetic subtypes of the syndrome (see Table 1), and is addressed in more detail in each of the corresponding sections below.

Principal clinical manifestations and comorbidities of Prader–Willi syndrome according to genetic subtype.

| Predominance in paternal microdeletion | Predominance in maternal disomy | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical manifestations | Affective instability | Social difficulties |

| Poorer verbal performance | Impulsivity | |

| Obsessive behavior | Tantrums, anger | |

| Self-harm (scratches) | Opposition, aggressiveness | |

| Obsession with food | Autistic-type behavior | |

| Comorbidities | Obsessive–compulsive disorder | Psychotic disorders |

| Autism spectrum disorder | ||

With regard to the clinical evaluation of the syndrome, only two scales have been specifically validated for PWS to date. The Prader–Willi Syndrome Behavior Questionnaire (PWSBQ), developed in 2014 by an Israeli group, consists of 37 items that analyze the behavioral disturbances in these patients.6 The Hyperphagia Questionnaire, which is somewhat more limited, exclusively focuses on the feeding problems of the PWS population.7 Although not specifically dealing with PWS, the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale has also been used to assess the obsessive symptoms of these patients.

Despite a number of attempts, no integral model capable of explaining the psychopathology of this syndrome is yet available. The attempted model that comes closest is probably that of Thuilleaux et al., who characterized these patients based on their symptoms and defined four clinical profiles: basic, impulsive, compulsive and psychotic.8 The present review contemplates no clinical classification and only describes the psychopathology of the syndrome in a global manner.

Intellectual disability and other cognitive deficitsPatient cognitive capacity in PWS ranges from borderline to moderate intellectual disability, with mean IQ scores of 65 points. A literature review found that only 5% of the patients had an IQ within the normal range,9 this often leading to learning difficulties and failure at school.

In the neuropsychological setting, the patients obtain poorer scores in executive functions, facial recognition, and planning and problem solving. Short-term memory is more affected than long-term memory, while auditory processing deficits are more marked than visual processing deficits.10 “Very low” scores in visuomotor integration and “below average” scores in visual perception and motor coordination have been detected.11

Language acquisition is delayed compared to the healthy population: in some cases it is not reached until 6 years of age. These communication difficulties have been described both in emitting and receiving information, with results lower than expected from the verbal intelligence of the patients: although they retain the ability to define words, limitations are observed in the construction of semantic relationships, in oral comprehension and in the forming of phrases.

Socially, at least 60% of the patients with PWS have problems identifying emotions, tolerating changes in routine, playing with other children of their age, understanding the concept of interpersonal distance, and feeling integrated. Compared to the healthy population between 7 and 12 years of age, children with PWS show an average delay of four years in theory of mind (i.e., the ability to understand that others have their own thoughts and to accept that they may be different from their own).12 All these deficits result in a lack of social skills, causing a progressive tendency toward isolation; moreover, in contrast to other neurodevelopmental disorders, the problem worsens with age.

With regard to the genetic subtype, patients with paternal microdeletion score better in social skills, while subjects with maternal disomy perform better in the verbal area, but are slower in cognitive processing.13

Self-harm and binge eatingIn association with the cognitive deficits, PWS is characterized by cognitive rigidity, perseveration and difficulties in tolerating changes in routine. Obsessive–compulsive behavior, with a significant impact upon social functioning and quality of life, is very common in this context. Regarding such behavior, special mention should be made of self-harm and obsession with food, often linked to compulsive intake. Less frequently, there have been reports of a need for order and hoarding behavior (mainly food). Both self-harm and eating obsession are more frequent and severe in the paternal microdeletion subtype.14

Up to 89% of all subjects with PWS exhibit self-harm; the most common manifestation is compulsive skin scratching (82%), which is often associated with wounds and overinfection. Other similar but less common forms of behavior include nose (28%) or rectum rubbing (6%), hand biting (17%), knocking the head (14%), or hair pulling (9%).15 According to cross-sectional studies, skin scratching increases during adolescence and remains stable during adulthood, with a predominance among females.16 Although generally considered to be compulsive, behavior of this kind can be influenced by patient impulsivity and is correlated to the degree of intellectual disability. Such behavior increases in the absence of adult supervision, thus suggesting that it may be sustained through an automatic reinforcement mechanism. With regard to the underlying etiopathogenesis, an increased pain threshold has been demonstrated in these patients, and altered interoceptive processing might contribute to this.17

With regard to eating obsession, functional magnetic resonance imaging has linked it to the reward circuit through the detection of decreased connections between the ventral striatum and the limbic system.18 It has also been associated with multiple neuroendocrine mechanisms involved in the regulation of appetite.19,20 In the event of unlimited access to food, patients with PWS may consume three times as many calories as controls matched for their body mass index (BMI) and age. This eating obsession is so intense that some authors have equated it to dependence on toxic substances, defining it as a true “food addiction”.21,22 Such craving for food, linked to the impulsivity of these patients, conditions food-seeking compulsions that have been related to an increased mortality due to accidents, particularly in young males,23 in addition to the abovementioned physical comorbidities. In some more extreme cases, complications have been reported in the form of potomania or even allotriophagia. Behavioral changes associated with food have not been shown to decrease with age in either of the two genetic subtypes.

Other behavioral disturbancesPatients with PWS often suffer mood fluctuations and an inability to control their emotions, leading to tantrums, impulsivity and even physical aggressivity in 83–97% of the cases.24 Compared with healthy children, such violent forms of behavior have a later onset, are of greater severity and are more persistent over time, until they begin to decline after 19 years of age.25 The outbursts of anger appear to be the expression of frustration, but can also be attributed to feelings of inferiority, lack of empathy, and an inability to understand the motivations of others. The opposition and hostility that often accompany PWS are found in this context, with lies, minor thefts, and other possessive or manipulative attitudes. A greater prevalence of such alterations has been detected in patients with maternal disomy.26

Lastly, there are also certain repetitive forms of behavior that resemble those of autistic patients, such as tics and stereotypical behavior. Restricted interests (typically puzzles) and social interaction difficulties (commented above) constitute other manifestations shared with autism. These aberrant attitudes also predominate in the maternal disomy subtype27 and can manifest in the absence or presence of comorbid autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The genetic study, associated symptoms, and the physical phenotype contribute to establish the differential diagnosis.

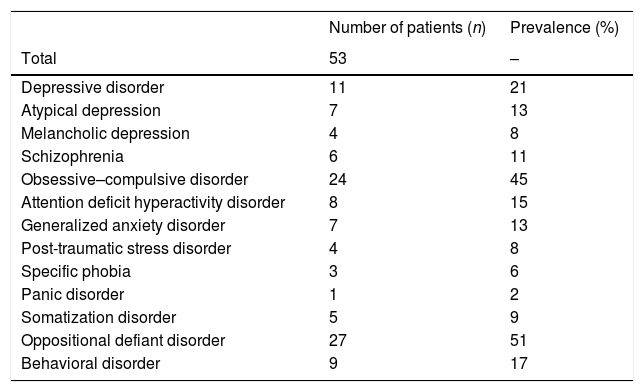

ComorbiditiesThe association of PWS with other psychiatric diagnoses is conditioned by multiple genetic, biological and environmental factors, and has been detected in up to 89% of all cases (see Table 2).28 The presentation is usually atypical in the earlier stages; any change in the usual behavioral patterns therefore should be regarded as suggestive of comorbidity.

Prevalence of the principal psychiatric comorbidities in a population of 53 patients (adolescents and adults) diagnosed with Prader–Willi syndrome.

| Number of patients (n) | Prevalence (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 53 | – |

| Depressive disorder | 11 | 21 |

| Atypical depression | 7 | 13 |

| Melancholic depression | 4 | 8 |

| Schizophrenia | 6 | 11 |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 24 | 45 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder | 8 | 15 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 7 | 13 |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 4 | 8 |

| Specific phobia | 3 | 6 |

| Panic disorder | 1 | 2 |

| Somatization disorder | 5 | 9 |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 27 | 51 |

| Behavioral disorder | 9 | 17 |

Source: Adapted from Shriki-Tal et al.28

Globally, 10–15% of all patients with PWS develop psychotic symptoms in late adolescence or early adulthood. In most cases, these symptoms are associated with an affective component and often present as hypomanic or depressive phases. The risk of suffering an affective disorder has been estimated to be 17.4%; by contrast, a higher prevalence of schizophrenia has not been confirmed, despite the existence of shared genetic and epigenetic alterations.29

There are differences in prevalence according to the genetic subtype of the patients. With regard to psychotic symptoms, the risk is very high (60%) in patients with maternal disomy and decreases to 20% in the case of the paternal microdeletion.30 The clinical presentation is usually in the form of cycloid psychoses associated with paranoid behavior, auditory hallucinations, and mood changes of subacute onset and variable intensity. Episodic patterns of euphoria or depression more consistent with bipolar disorder have also been reported, however.

In addition to suffering these symptoms more frequently, patients with maternal disomy tend to have a poorer prognosis, an increased risk of psychotic recurrence, and possibly a poorer response to treatment.31 This situation is not seen in depressive relapses, which occur with a prevalence of 20–25% in both genetic subtypes.32 By contrast, the paternal microdeletion has been linked in males to an increased risk of depression, aggression and dependent personality disorder.33 Despite this, it is generally considered that recurrences are rather uncommon once stabilization has been achieved with antipsychotic treatment.

Catatonia may be another manifestation of psychosis, as has been reported in case series. Despite this, no specific literature is available regarding its prevalence, clinical characteristics or therapeutic approach in comorbidity with PWS.

With regard to the underlying etiology, the development of psychotic symptoms may be related to the overexpression of maternal genetic material. A study published in 201734 reported that the high risk of psychosis in individuals with maternal disomy may result from the aberrant microstructural development of white matter. With regard to the affective symptoms, the small nucleolar RNA fragment (sno)RNA HBIII-52 has been implicated by altering the serotonin 2C receptor.35 Apart from these findings, the underlying causal mechanism remains unknown. Current efforts should focus on identifying those patients with PWS who are at increased risk of developing psychosis, as this would allow better characterization of the prodromal symptoms and would help in the design of clinical trials.

Autism spectrum disorderAlthough strictly speaking most individuals with PWS do not meet the criteria for autism spectrum disorder (ASD), there are similarities in the clinical presentation of both conditions: cognitive rigidity, perseveration, reluctance to change, rituals, repetitive behavior, restricted interests, and social difficulties. Some of the mutations identified in segment 15q11-q13 are present in both PWS and ASD, which may indicate a common genetic background.

According to the available evidence, such comorbidity is common, but is also influenced by the genetic subtype involved: in patients with idiopathic ASD, maternal disomy is present in 1–3% of the cases, while paternal microdeletion is less common.36 These data, based on family interviews and clinical scales, explain the greater coincidence of both diagnoses in the maternal disomy subtype (35–37.7%), with much lower values in the case of the paternal microdeletion (18–18.5%).37

In addition to the genetic subtype, the presence of ASD has been correlated to males, but not to drug treatment, the BMI, socioeconomic status, or the educational level of the parents. Broadly speaking, patients with such comorbidity, unlike those with PWS without ASD, have more stereotypias and restricted interests, and score poorer in terms of IQ and social skills. The most common form of self-harm in PWS consists of skin scratches, while bites or blows predominate in ASD. In comparison with Asperger's syndrome, different timing has been reported in the development of autistic-type behaviors, which is infrequent in early childhood, more prominent from 6 years of age, and comparable to those of Asperger's syndrome from 13 years of age.38

Obsessive–compulsive disorderIt is not clear to what extent the types of obsessive-compulsive behavior typically associated with PWS (food obsession, compulsive scratching, etc.) may overlap with well established obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD). Indeed, some of the brain connectivity alterations described for OCD (both between subcortical structures and between the prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia) can also be found in patients with PWS. As has been seen, obsessive symptoms occur with greater frequency and severity in patients with paternal microdeletion, which should cause us to expect a greater prevalence of comorbid OCD in this subpopulation, which is estimated to be 26%.39

As regards the differential diagnosis, obsessive thoughts in PWS are less apparent than compulsive behavior. The predominant compulsions are more related to self-harm and to the search for food, while those classically associated with OCD (hand washing, checking behavior) are more rarely observed. These compulsive acts typically do not respond to the need to relieve anxiety or stress, but are simply performed because they are pleasant.40

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorderThe behavioral disturbances in PWS include emotional lability, tantrums and outbursts of anger, which are also found in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The available evidence on the coincidence of both diagnoses is rather limited. According to a study published in 2005,41 the prevalence of ADHD reached 25.9% in a cohort of 58 patients with PWS. Of clinical significance was the fact that behavioral problems were also reported in 22.4% of the cases, and impulsivity and hyperactivity problems in 19%. Another study of similar characteristics42 conducted in 2012 in 24 patients with PWS found the prevalence of ADHD to be 21%. It should be noted that these results were based on scales administered to the relatives. Given that no direct patient assessments were made, this could represent a source of bias.

Sleep disturbancesDue to hyperphagia and obesity, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome is very common (seen in 79.9% of all patients).43 Systematic screening and, if sleep disturbances are suspected, referral to a specialized pulmonologist are generally recommended.

Excessive daytime sleepiness often accompanies PWS, with an onset in childhood, and occurs more frequently than in other intellectual disabilities. It is not uncommon for subjects to become sleepy during the first years of life and, when older, to present cataplexy-like symptoms in up to 16% of all cases (although in general there are no other clinical signs suggestive of narcolepsy).44 The SNORD116 gene, which is altered in PWS, has been implicated in both circadian rhythm control and hyperphagia control.45 In fact, excessive daytime sleepiness persists despite treatment for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and has been positively correlated to the behavioral disturbances that accompany PWS.

Other common disorders include snoring, difficulties in waking up, and decreased rapid eye movement (REM) latency.

Other comorbiditiesIncreased levels of anxiety and feelings of insecurity often translate into a hypersensitivity to stress, an inability to tolerate uncertainty, somatic complaints, dependency and a constant need for reassurance. A descriptive study in the adult population46 recorded an increased prevalence of anxiety disorder and adjustment disorder with a predominance of anxiety (38%). The same sample also documented cases of intermittent explosive disorder (30%), with a 2:1 male predominance. Another study in younger patients (7–17 years of age)47 revealed an increased frequency of oppositional defiant disorder (20%) regardless of age, gender, genetic subtype or IQ.

TreatmentThe use of drugs in PWS has had only a limited effect in terms of patient behavioral control. However, drug administration is common for the management of both symptoms and comorbidities.

The only specifically approved treatment for children with PWS is growth hormone, which has been shown to reduce hypotonia and the risk of obesity, partially normalize physical and psychological development, and improve cognitive ability, while reducing behavioral problems.48 Other studies also indicate an improvement in the signs of clinical depression and hedonic abilities, though at the risk of enhancing ADHD symptoms.49 Beyond its metabolic benefits, growth hormone has shown its value in improving mental agility, cognitive flexibility, reaction time, attention capacity and quality of life. However, according to most clinical guides, growth hormone deficiency should be demonstrated by stimulation tests in order for it to be indicated in the adult population, and this undoubtedly complicates its use. The administration of growth hormone is controversial due to the possibility of adverse effects, though this can be remedied through good patient monitoring.50

The combination of naltrexone and bupropion exerts a synergistic effect in the general population that facilitates a decrease in food intake and weight gain. For this reason, such treatment has been used in PWS in application to hyperphagia and impulsivity, although no clinical trials are currently available in this regard.51 In principle, the use of metformin in children with PWS who have insulin resistance and glucose intolerance should also improve hyperphagia questionnaire outcomes, food-related distress, and patient ability to stay away from food.52 On an experimental basis, good results have been obtained in terms of dietary control with the administration of GLP1 analogs (exenatide,53 liraglutide54) and a deacylated ghrelin analog,55 but not with long-acting somatostatin analogs (although capable of modifying the ghrelin levels, these did not achieve changes in weight, body composition, appetite or attitude toward food).56 To date, all other drug alternatives have been found to be ineffective in reducing food intake. Bariatric surgery does not decrease hyperphagia or achieve sustained weight loss, and is therefore likewise not useful over the middle or long term.57

Considering the high frequency of behavioral disturbances, most clinicians choose to use low-dose antipsychotics. Of these, risperidone is the most widely used drug,58 though a good response to aripiprazole, quetiapine, chlorpromazine, haloperidol and ziprasidone has also been reported. Paradoxically, a study published in 2015 showed that the use of antipsychotics in PWS may be associated with weight loss,59 probably as a result of better behavioral control. Replacement therapy for hypogonadism, which is present in up to 50% of all cases, has been shown to be safe, and does not necessarily imply an increase in aggressiveness or behavioral problems.60,61

For obsessive symptoms, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are the alternative gold standard for the control of tantrums and compulsions. Of all the SSRIs, fluoxetine is the antidepressant for which most experience has been gained in this field,58 though there is no evidence of its usefulness as an appetite inhibitor in patients with PWS. Topiramate is another equally applicable option for reducing self-harm and aggressiveness, due to its anti-impulsive effect. Its capacity to curb food-related behavior has yielded contradictory results, however.62 Benzodiazepines have been used successfully as supportive treatment, but they should be avoided because of the risk of iatrogenic effects.

Beyond drug treatment, an environmental approach is crucial, often including the need to keep food locked under key, careful monitoring of intake, diet and exercise, and specialized nutritional counseling. Behavioral measures (accompaniment, keeping nails short) and barrier mechanisms (bandages, topical antibiotics) also reduce self-inflicted skin injuries and possible infections. Psychotherapies such as applied behavioral analysis, used in autistic disorder, have also shown promising results in the management of behavioral disorders. The importance of facilitating the transition from pediatrics to adult care and of preventing loss to follow-up of these patients by Endocrinology should be stressed.63

Very few studies have analyzed the treatment of psychiatric comorbidities in PWS. Consequently, the concurrence of another mental disorder should be addressed on an empirical basis with the conventional alternatives, whether pharmacological or psychotherapeutic. The use of antipsychotics, regardless of the genetic subtype and history of previous psychotic episodes, has been shown to decrease the risk of major psychiatric disorders during follow-up.64

Finding new strategies for the management of these patients has become a challenge for the scientific community. Oxytocin administration may be associated with better social and behavioral performance, but the results are inconclusive at this time.65 Another promising alternative is N-acetylcysteine, a modulator of the glutaminergic excitatory pathway, which has been related to a decrease in skin scratching behavior.66 In a controlled environment, transcranial direct current stimulation67 and vagus nerve stimulation therapy68 decreased aberrant behavior associated with food. Excessive daytime sleepiness, specifically, has improved with modafinil in some cases.69

A highly recommendable document is the Prader–Willi Syndrome Management Guide (Guía da actuación en el syndrome Prader–Willi), developed by the public health system of the Basque Country and aimed at healthcare professionals, which develops several of the aspects of the present review in greater detail.70 The same can be said of Chapter 7 of the monograph Imprint Diseases: Good Clinical Practice Guidelines (Enfermedades de la impronta: guías de buena práctica clínica), which was written by members of our team and provides a comprehensive review of this genetic disorder and its therapeutic options.71 With regard to information for users and their caregivers, the Handbook for Family Members of People with Prader–Willi Syndrome (Manual para familiars de personas afectadas por el syndrome de Prader–Willi), published by the Prader–Willi Syndrome Association of Andalusia (Asociación Síndrome Prader–Willi de Andalucía [ASPWA]), collects experiences and testimonies from both patients and their relatives, and describes them in a language that is suitable for all audiences.72

ConclusionsPrader–Willi syndrome is a genetic disorder characterized by a specific physical and mental phenotype. The associated psychopathological disorders include cognitive deficits, intellectual disability, difficulties regarding social interaction, obsession with food, compulsive skin scratching, tantrums, mood fluctuations, impulsivity, and autistic-type behavior. Comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders is a common finding that often complicates the diagnosis and demands an integral approach.

The management of PWS requires biopsychosocial intervention to secure optimal symptom control. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation programs are the key tool for the treatment of patients and the support of their relatives and caregivers. Generally, a combination of psychotherapy, psychotropic drugs and specific behavioral management interventions are chosen. Since no evidence-based clinical guidelines are available, management should be individualized based on the needs of each case.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Guinovart M, Coronas R, Caixàs A. Alteraciones psicopatológicas en el síndrome de Prader-Willi. Endocrinol Diabetes Nutr. 2019;66:579–587.