DiaScope® is a software to help in individualized prescription of antidiabetic treatment in type 2 diabetes. This study assessed its value and acceptability by different professionals.

Material and methodsDiaScope® was developed based on the ADA-EASD 2012 algorithm and on the recommendation of 12 international diabetes experts using the RAND/UCLA appropriateness method. The current study was performed at a single session. In the first phase, 5 clinical scenarios were evaluated, selecting the most appropriated therapeutic option among 4 possibilities (initial test). In a second phase, the same clinical cases were evaluated with DiaScope® (final test). Opinion surveys on DiaScope® were also performed (questionnaire).

ResultsDiaScope® changed the selected option 1 or more times in 70.5% of cases. Among 275 evaluated questionnaires, 54.0% strongly agree that DiaScope® allowed finding easily a similar therapeutic scenario to the corresponding patient, and 52.5 among the obtained answers were clinically plausible. Up to 58.3% will recommend it to a colleague. In particular, primary care physicians with >20 years of professional dedication found with DiaScope® the most appropriate option for a particular situation against specialists or those with less professional dedication (p<0.05).

DiscussionDiaScope® is an easy to use tool for antidiabetic drug prescription that provides plausible solutions and is especially useful for primary care physicians with more years of professional practice.

DiaScope® es un software de ayuda a la prescripción individualizada del tratamiento antidiabético en la diabetes tipo 2. Este estudio evalúa la utilidad y aceptabilidad de dicha aplicación entre diferentes profesionales.

Material y métodosDiaScope® fue desarrollado en base al algoritmo de la ADA-EASD 2012 y con las recomendaciones de 12 expertos en diabetes internacionales, usando el método RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. El presente estudio se llevó a cabo en una sola reunión. En una primera fase, se evaluaron de 5 escenarios clínicos, eligiendo la opción terapéutica más adecuada entre 4 posibilidades (test inicial). En una segunda fase, estos mismos casos clínicos fueron evaluados con DiaScope® (test final). Además, se realizaron encuestas de opinión sobre DiaScope® (cuestionario).

ResultadosDiaScope® modificó la opinión una o más veces en un 70,5% de los casos. De los 276 cuestionarios evaluados, un 54,0% estuvieron muy de acuerdo en que DiaScope® permitía encontrar con facilidad un escenario terapéutico similar al de un paciente determinado, y un 52,5% en que las respuestas obtenidas eran clínicamente plausibles. Hasta un 58,3% se lo recomendaría a un compañero. En particular, los médicos de Atención Primaria y>20 años de ejercicio profesional encontraron con DiaScope® la opción terapéutica más adecuada para una situación concreta, frente a médicos de Atención Especializada o con menos años de ejercicio profesional (p<0,05).

DiscusiónDiaScope® es una herramienta de ayuda en la prescripción de antidiabéticos, de uso sencillo, con soluciones plausibles, especialmente útil en profesionales de Atención Primaria, con más años de ejercicio profesional.

The European Commission has pointed out that diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most important chronic diseases, and has developed a number of plans and projects to learn more regarding its prevalence and the economic burden associated with it, and to implement preventive measures.1 The latest report on diabetes published in 2016 by the World Health Organization2 estimated that in 2014, 422 million adults were diabetic, as compared to 108 million in 1980. Diabetes increases the risk of premature death, but is also associated with an increase in complications such as myocardial infarction, cerebral infarction, kidney failure, vision loss, etc. The disease is associated with high costs for healthcare systems and accounts for a major loss of productivity.3

Intensive treatment of hyperglycemia may contribute to prevent or delay the progression of chronic complications of diabetes. Individualized treatment to achieve or maintain glucose control goals is critical. One of the latest published guidelines for the treatment of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes4 concerns a treatment algorithm that contemplates the combination of up to 10 second-line therapy classes. The selection of the most appropriate treatment for a specific patient may be a complex task, particularly for less experienced professionals.

Computerized clinical decision support systems are designed to help with, and improve, the clinical decision-making process.5 Although there is little consistency in the way these systems work, they usually make it possible to enter the characteristics of individual patients to generate individualized therapeutic recommendations using algorithms integrated in the software.6 Based on this premise, a group of European diabetes experts used the best available scientific evidence and the RAM method (RAND Appropriateness Method, a modified Delphi approach) to design DiaScope®, a system to help in the individualized prescription of antihyperglycemic treatment in type 2 diabetes.7 This tool has not yet been evaluated in specific clinical settings. This study was therefore designed to assess the value and acceptability of the application in a number of real clinical scenarios with the collaboration of primary care physicians and specialists in several Spanish hospitals.

Patients and methodsDevelopment of DiaScope®The main objective of DiaScope® was to translate current evidence, particularly the recommendations of the algorithm of the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD)–ADA-EASD 2012–,8 into clinical practice. This software was also implemented after taking into consideration independent suggestions from 12 diabetes experts from different European countries. At an early meeting, and based on a literature review, this group of experts proposed clinical criteria for the population to be considered for evaluation using the DiaScope® tool.7 In the first version of DiaScope®, 175 different clinical contexts in which glucose control was inadequate with oral drugs and/or GLP-1 receptor agonists used were analyzed. Recommendations for each specific situation were prepared using the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method developed by the RAND Corporation and the University of California–Los Angeles.9 The clinical scenarios evaluated resulted from permutations of the clinical variables considered relevant for treatment selection, namely: current treatment, anticipated HbA1c decrease to individual goals, the risk of hypoglycemia (low, moderate/high), the body mass index (<25; 25–29.9; ≥30kg/m2), life expectancy (≥2 years and <2 years), comorbidities (coronary disease/stroke, heart failure, advanced microvascular complication, moderate kidney failure, moderate/severe liver failure, and dementia).

Study proceduresThe value and acceptability of DiaScope® were assessed in a single session. In the first phase of the study, before its introduction, five clinical scenarios of patients with type 2 diabetes were presented, for which the best of four possible therapeutic actions had to be selected (the initial test). Subsequently, attendees assessed the same clinical cases again, but this time with the help of DiaScope®, and any change in prescription from the first phase was recorded (the final test). At the end of the session, a survey on the value of DiaScope® (a questionnaire) was distributed.

The professionals invited to participate were mainly primary care physicians and other specialists (endocrinologists, internists). From the onset, each physician was assigned an ID code to preserve the confidentiality of their data and to ensure traceability during the different study phases.

Assessment criteriaTo assess the value of DiaScope®, the primary objective of the study, changes in treatment selection in the five clinical scenarios used before and after its use were recorded. The number of changes was analyzed as a function of the prescribers’ characteristics. The secondary objective of the study was to ascertain the level of acceptability of the tool. This was done by means of a survey consisting of six questions with five choices: 1, strongly disagree; 2, partly disagree; 3, undecided; 4, partly agree; 5, strongly agree. The final question of the survey attempted to record the features that best defined DiaScope®. This was an open-ended question where the physician could indicate several options.

The following data on the prescribers were also collected: sex: male/female; urban setting: yes/no; specialty: primary care/endocrinology/internal medicine/other; resident: yes/no; years of professional practice: <10/11–20/>20; number of DM patients per week: <10/11–20/>20; prior experience with GLP-1 RAs (glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists): yes/no; prior experience with insulin: yes/no. Clinical case assessments before and after the use of DiaScope® and survey questions were recorded in case report forms designed for that purpose.

Statistical analysisData from the case report forms were recorded in a specifically designed database consisting of three sheets: one for the initial test, one for the final test, and the satisfaction survey. All three sheets shared the participating physician's ID code. A new database was created with which traceability could be established through the physician's code. To develop this database, a filter was applied for each meeting site, along with the physician's code and the results from the clinical case assessment; double entry records allowed us to detect and rectify any differences. The database quantified the number of changes made after using DiaScope®, and gave a detailed description (number and %) of the prescribers’ characteristics. Finally, records that could not be traced using the code were discarded. However, the survey was also analyzed for all records with an available answer.

Several comparisons were made using a Chi-squared test to analyze variables that assessed value and acceptability as a function of the various characteristics of the prescribers. Values of p<0.05 were considered significant. On the other hand, as the distribution of the physicians’ specialties was not homogeneous, this variable grouped primary care versus all other specialties, and the number of changes and the survey were analyzed again. Analyses were performed using software SPSS vs23.0.

Finally, an exploratory multivariate analysis was performed to try and differentiate the characteristics of the physicians who appeared to find the DiaScope® most useful. For this purpose, the survey question “I can find the most adequate treatment option for a specific situation” was selected as the most relevant and, thus, as the dependent variable of the model. The variables most significant for this question in the Chi-squared tests were introduced. To create the model, a significance level of p<0.05 was again considered for each variable.

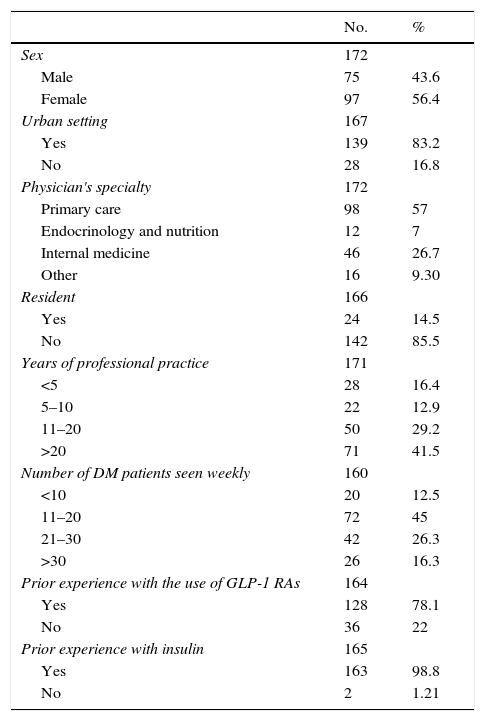

ResultsThe original database contained 301 records at the initial test, and 277 at the final test. The cleaned-up database that permitted traceability included 173 records only. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of the prescribers. An assessment survey was collected for 276 records. As Fig. 1 shows, prescribers gave a very positive evaluation of DiaScope®. Fifty-four percent strongly agreed that DiaScope® allowed them to easily find a treatment scenario similar to that of a given patient, and 52.5% that the responses obtained were clinically plausible; 45.6% strongly agreed that DiaScope® helped them to keep in mind the most relevant clinical characteristics when changing treatment; and 47.1% partly agreed that they would use DiaScope® in daily clinical practice to guide decision making. Also, 58.3% would recommend it to a colleague as support in regular clinical practice. The responses in the records that could not be traced back were similar. Table 2 shows the answers to the open question about the characteristics that best define DiaScope®.

Baseline characteristics of prescribers.

| No. | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | 172 | |

| Male | 75 | 43.6 |

| Female | 97 | 56.4 |

| Urban setting | 167 | |

| Yes | 139 | 83.2 |

| No | 28 | 16.8 |

| Physician's specialty | 172 | |

| Primary care | 98 | 57 |

| Endocrinology and nutrition | 12 | 7 |

| Internal medicine | 46 | 26.7 |

| Other | 16 | 9.30 |

| Resident | 166 | |

| Yes | 24 | 14.5 |

| No | 142 | 85.5 |

| Years of professional practice | 171 | |

| <5 | 28 | 16.4 |

| 5–10 | 22 | 12.9 |

| 11–20 | 50 | 29.2 |

| >20 | 71 | 41.5 |

| Number of DM patients seen weekly | 160 | |

| <10 | 20 | 12.5 |

| 11–20 | 72 | 45 |

| 21–30 | 42 | 26.3 |

| >30 | 26 | 16.3 |

| Prior experience with the use of GLP-1 RAs | 164 | |

| Yes | 128 | 78.1 |

| No | 36 | 22 |

| Prior experience with insulin | 165 | |

| Yes | 163 | 98.8 |

| No | 2 | 1.21 |

Characteristics best defining DiaScope® according to the prescribers.

| Open question | Number [276] | % | Number [173] | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With DiaScope® I can better assess all possible treatment options for a given patient | 203 | 73.6 | 127 | 73.4 |

| With DiaScope® I can find the best treatment option for a specific situation | 181 | 65.6 | 113 | 65.3 |

| DiaScope® is a complement to clinical guidelines | 176 | 63.8 | 111 | 64.2 |

| DiaScope® can help me avoid potential drug prescription errors | 163 | 59.1 | 108 | 62.4 |

| DiaScope® is of great help in patients with comorbidities | 138 | 50 | 85 | 49.1 |

| DiaScope® is not intended to be in conflict with local prescription guidelines | 102 | 37 | 56 | 32.4 |

| DiaScope® provides the most effective treatment options for a given patient according to the scientific evidence | 183 | 66.3 | 112 | 64.7 |

| DiaScope® may even be helpful in teaching medical students | 136 | 49.3 | 77 | 44.5 |

Analysis of prescription changes in clinical cases to assess the value of DiaScope® showed that only 29.5% made no changes after using the system. Thus, the use of DiaScope® modified opinion regarding treatment one or more times in 70.5% of cases. Analysis of the number of changes as a function of the prescriber's characteristics showed no significant relationship.

As regards DiaScope® acceptability in traceable records, primary care prescribers were more likely to say that DiaScope® helped them to keep in mind the patient's clinical characteristics when changing treatment; these differences were significant when compared to specialized care practitioners. Moreover, those prescribers who saw fewer patients per week, residents, and those with no prior experience with GLP-1 RAs stated that before using DiaScope® they had found it more difficult to find the best treatment option for a patient (Table 3).

Acceptability depending on the prescribers’ characteristics.

| Prescriber's specialty (n=171) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Specialist | p | |

| DiaScope®helps me keep in mind the patient's relevant clinical characteristics when changing treatment | 0.025 | ||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 2 (2.7%) | |

| 2 | 2 (2.1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| 3 | 6 (6.2%) | 12 (16.2%) | |

| 4 | 37 (38.1%) | 30 (40.5%) | |

| 5 | 52 (53.6%) | 30 (40.5%) | |

| DM patients seen weekly (n=160) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 | 11–20 | >20 | p | |

| Before using DiaScope®, I had difficulty in finding the best treatment option for a given patient with type 2 diabetes | 0.001 | |||

| 1 | 2 (10%) | 10 (13.9%) | 15 (22.1%) | |

| 2 | 0 (0%) | 21 (29.2%) | 26 (38.2%) | |

| 3 | 7 (35%) | 13 (18.1%) | 15 (22.1%) | |

| 4 | 9 (45%) | 22 (30.6%) | 9 (13.2%) | |

| 5 | 2 (10%) | 6 (8.3%) | 3 (4.4%) | |

| Resident (n=166) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| Before using DiaScope®, I had difficulty in finding the best treatment option for a given patient with type 2 diabetes | 0.033 | ||

| 1 | 25 (17.6%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| 2 | 45 (31.7%) | 2 (8.3%) | |

| 3 | 28 (19.7%) | 7 (29.2%) | |

| 4 | 37 (26.1%) | 10 (41.7%) | |

| 5 | 7 (4.9%) | 3 (12.5%) | |

| Prior experience with the use of GLP-1 RAs (n=164) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| Before using DiaScope, I had difficulty in finding the best treatment option for a given patient with type 2 diabetes | 0.009 | ||

| 1 | 24 (18.8%) | 3 (8.3%) | |

| 2 | 40 (31.3%) | 6 (16.7%) | |

| 3 | 29 (22.7%) | 7 (19.4%) | |

| 4 | 31 (24.2%) | 14 (38.9%) | |

| 5 | 4 (3.1%) | 6 (16.7%) | |

DM, type 2 diabetes; 1, strongly disagree; 2, partly disagree; 3, undecided; 4, partly agree; 5, strongly agree.

With regard to the open question about the characteristics that define DiaScope®, analyzed according to the prescribers’ characteristics, primary care physicians answered more frequently that with DiaScope® they were able to find the best treatment option for a specific situation; the differences between them and specialized care physicians were significant. The same occurred with physicians with more than 20 years of practice as compared to the rest, and with non-residents as compared to residents (Table 4).

Key question by prescriber's specialty.

| Prescriber's specialty (n=172) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Specialist | p | |

| I can find the best treatment option for a specific situation | 0.020 | ||

| 0 | 27 (27.6%) | 33 (44.6%) | |

| 1 | 71 (72.4%) | 41 (55.4%) | |

| Years of professional practice (n=171) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <10 | 11–20 | >20 | p | |

| I can find the best treatment option for a specific situation | 0.048 | |||

| 0 | 24 (48%) | 16 (32%) | 19 (26.8%) | |

| 1 | 26 (52%) | 34 (68%) | 52 (73.2%) | |

| Resident (n=166) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | p | |

| I can find the best treatment option for a specific situation | 0.033 | ||

| 0 | 45 (31.7%) | 13 (54.2%) | |

| 1 | 97 (68.3%) | 11 (45.8%) | |

1, indicated by physician.

An exploratory multivariate analysis was conducted where the dependent variable was the open question considered most relevant, that is, «With DiaScope® I can find the best treatment option in a specific situation». The variables included in this model were those which were significant for this question in the comparative analyses: medical specialty, being a resident physician, and years of practice. None of the variables included in the model was significant. Therefore, a model to distinguish which type of prescriber was helped the most by DiaScope® could not be generated.

An additional exploratory univariate analysis was performed for each variable included in the model. The results show that primary care physicians considered DiaScope® 2.12 times more useful as compared to specialists. Non-residents found it 2.55 times more useful as compared to residents, and those with more than 20 years of experience found it 2.53 times more useful than those with less experience. The coefficients found in the univariate analyses decreased when they were all integrated in the multivariate analysis; this was most remarkable for the years of experience variable. It suggests that these variables were interrelated, and thus showed colinearity.

DiscussionDiaScope® was developed as a software tool to help in the treatment of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, using the recommendations in the ADA-EASD 2012 algorithm and those based on the best current clinical evidence. When these were not available, the clinical judgment of experienced diabetologists in various clinical situations was used. The validated method used was the RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method. A review conducted by Carg et al.10 showed that the development of computerized systems for clinical decisions often includes expert opinions, in addition to clinical guidelines.

We therefore think that this software, which incorporates routinely used clinical variables (baseline and target glycosylated hemoglobin levels in each case, the risk of hypoglycemia, the degree of obesity, life expectancy, comorbidities, etc.) and contemplates a wide variety of possible clinical scenarios, with the additional contribution of expert diabetologists, is very likely to be accepted by physicians who treat diabetic patients. In this regard, the prescribers’ perception of the DiaScope® tool was very good. More than half of the prescribers considered that with DiaScope® they found patterns similar to those in their usual clinical practice, and that the answers obtained were clinically plausible. Thus, the prescribers stated that this tool could be useful when taking decisions, and that they would recommend it to colleagues.

It should be noted that the vast majority of prescribers changed their initial opinion regarding treatment after using DiaScope®. However, an analysis of these changes according to the prescribers’ characteristics showed no significant influence of any of these characteristics. This may be due to the descriptive nature of the study and to the lack of uniformity of the prescribers’ characteristics. In any case, it was the prescriber who made the final decision considering the different options and recommendations in each case. In studying the main characteristics of a successful clinical decision system, such suggestions must be considered relevant for improving patient care.11

Other important factors are that the tool should be easy to use and that the recommendation should be automatic and be part of the physician's practice. All these points were taken into consideration in the development of DiaScope®. Among the parameters for obtaining a recommendation, the physician may indicate the characteristics that best define the patient by using only five items (Fig. 2), actively introducing only the patient's latest HbA1c level and the control goal.7 The prescriber may thus quickly decide, based on the patient's characteristics, whether treatment should be changed or not, so avoiding an excessive delay in decision making.12

When survey responses on the value of DiaScope® were analyzed as a function of physician characteristics, primary care physicians stated more often than specialists that the tool helped them to keep in mind the patient's clinical characteristics when treatment had to be changed. Furthermore, the exploratory univariate analysis showed that primary care physicians felt 2.12 times more often than specialists that with DiaScope® they could find the best treatment option in specific situations. The systematic review conducted by Cleveringa6 also supported the values of these systems in primary care. Many studies related to diabetes support systems have been conducted in primary care13 because this is where the disease is managed in most countries.14,15 Thus, we think that a tool such as DiaScope®, which allows for the better individualization of treatment, may improve care for type 2 diabetics, especially in primary care.

Another interesting aspect is that before using DiaScope®, the prescribers stated that they had problems in finding the best treatment option for a given patient. This tool was therefore significantly more useful for prescribers providing weekly care to only a few patients, prescribers in training (residents), and those with no experience in using GLP-1 RAs (less experienced in prescribing new treatments for diabetes). In this sense, primary care physicians with more than 20 years of practice considered, significantly, that with DiaScope® they could find the best treatment option in specific situations. This may indicate that based on their experience, non-resident physicians need, and are able to, prescribe treatment, but that when they have the help of DiaScope®, they find it easier to access, and also appreciate receiving, a therapeutic recommendation in a simple form. Therefore, and although a model could not be found of the ideal prescriber for whom DiaScope® was most useful, there is evidence that this system may be most helpful for primary care prescribers with many years of practice and probably less updated knowledge regarding new drugs, and who are usually more reluctant to incorporate new initiatives into their daily practice.16 Although the factors influencing the participation of primary care physicians in patient care programs are not well known, a study conducted in the United Kingdom17 showed that factors that induce participation in programs to optimize patient care included, as would be expected, the desires to improve patients’ health and to maintain professional autonomy.

A recently published study18 followed a methodology similar to that of our study, based on the presentation of clinical cases and the subsequent evaluation of the software with a five-choice questionnaire. Qualitative evaluation has been used in multiple studies to assess computerized decision-making tools in diabetes19 and other conditions. A significant proportion of articles reviewing the published studies are therefore based on systematic descriptive reviews6,10,11,13,20 rather than on quantitative review methods, such as meta-analyses. Thus, both the analysis and the design of our study are consistent with what has been previously published. Moreover, it seems reasonable to ascertain the opinion of professionals before they use the system in daily clinical practice, which, as in other studies found in the literature,10 is what this study has done.

The strengths of our study include the use of the previously validated RAND/UCLA Appropriateness Method, together with published evidence regarding diabetes treatment and the informed opinions provided by a panel of international experts, to develop the tool. Also, the study was conducted in a single session to minimize the loss of participating subjects. This allowed for a very high number of prescribers at the end of the session (277) as compared to similar studies.13,18,19 It should be noted, however, that only 173 records (62.4%) could be analyzed, since we only took into consideration the number of prescribers who completed the two tests and the final survey. The reason for such a marked reduction was that if the prescriber's code was omitted at the time of data collection, we were unable to discover which prescriber had provided a given evaluation of the value and acceptability of DiaScope®. This is the reason why the main analysis of this database was performed on a smaller number of records, although with the assurance that the prescribers analyzed met the study requirements. Even so, as shown by Fig. 1 and Table 3, the perception of software acceptability was similar for the total records and for the traceable ones (62.4%). Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the results obtained with the smaller sample can be extrapolated to the total sample. In any case, it is possible that one of the factors contributing to the impossibility of finding a model to identify the ideal prescriber for DiaScope® was the reduction in the number of records included in the final analysis.

Finally, as the software was developed according to the 2012 ADA/EASD recommendations, yearly updates are planned to make DiaScope® a tool that can be adapted to new evidence and treatment options. In fact, there is already a new version that includes SGLT-2 inhibitors (sodium-glucose cotransporter type 2 inhibitors) among the treatment options and contains an insulinization module. The next step after this study should be the implementation of DiaScope® in daily clinical practice to assess its impact on the improvement of metabolic control in patients, the reduction of clinical inertia, and a decrease in the chronic complications of diabetes, etc.

ConclusionsDiaScope® is a helpful tool for deciding on drug prescription, is easy to use, and provides plausible solutions, making it especially useful for primary care physicians and those with many years of professional practice. In general, the prescribers’ perception of the DiaScope® tool was good. More than half of the prescribers considered that with DiaScope® they found patterns similar to those in their standard clinical practice, and that the responses obtained were clinically plausible. DiaScope® was therefore considered very useful for taking decisions, and could be recommended to colleagues. Moreover, a wide majority considered that DiaScope® allowed for a better assessment of the different treatment options to find the most adequate treatment for a given patient. Most prescribers changed their opinion regarding their initial prescription after using DiaScope®.

FundingThe study was funded by Novo-Nordisk.

Authorship/collaboratorsJavier Ampudia: design, evaluation, and manuscript drafting.

Javier G-S: design, evaluation, and manuscript revision.

Tra-Mi Pan: design, evaluation.

Manuela Rubio: design, evaluation.

Conflicts of interestDr. Ampudia has received fees for lectures and/or consultancy, and has participated in clinical trials funded entirely or in part by Novo-Nordisk.

Dr. Soidan states that he has no conflicts of interest with Novo Nordisk in connection to the present study.

Please cite this article as: Ampudia-Blasco FJ, García-Soidán FJ, Rubio Sánchez M, Phan T-M. Validación en situaciones clínicas reales del DiaScope®, un software de ayuda al profesional sanitario en la individualización del tratamiento antidiabético en la diabetes tipo 2. Endocrinol Nutr. 2017;64:128–137.