While most small cell neuroendocrine carcinomas (SCNEC) arise from the bronchopulmonary tree, some have other origins. Primary SCNECs of lymph nodes are extremely rare. To date, only a few cases have been reported. Management of this condition is quite challenging since no clinical guidelines are available or published, and good-quality evidence is lacking.

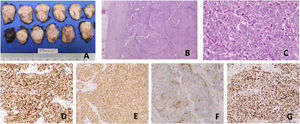

A 61-year-old male presented with a left inguinal mass of 4 months’ evolution. Past medical history was unremarkable, except for urolithiasis, and he denied taking any medication. No risk factors were present (no exposure to tobacco) and there was no family history for neoplastic disease. He was asymptomatic, and at physical examination nothing relevant was found. Laboratory workup (complete blood cell count, renal function and electrolytes, hepatic tests, calcium-phosphorus metabolism, high sensitivity c-reactive protein, sedimentation rate, serum protein electrophoresis) was normal. Left inguinal ultrasonography showed a 4-cm well-circumscribed hypoechoic lesion, suggestive of adenopathy. Fine needle aspiration cytology revealed small to medium-sized blue cells with scant cytoplasm, pleomorphic nuclei, and molding. Surgical excision was performed, and anatomopathological analysis established the diagnosis of small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma: immunohistochemistry showed positivity for synaptophysin, CK AE1/AE3 (perinuclear dot-like stain), CAM5.2, chromogranin and was negative for TTF-1 and CK20, with a Ki-67 score of 80–90% (Fig. 1).

Morphological and immunohistochemical features of a small cell NEC. (A) Lymph node with 22g and 52mm×30mm×21mm. (B) HE 40×, histopathology showing organoid and diffuse growth with necrosis. (C) HE 400×, tumor cells show round nuclei with fine granular chromatin, inconspicuous nucleoli, nuclear molding, high nuclear-cytoplasmic ratio, scant cytoplasm, and mitotic figures. Diffuse immunoreactivity to (D): cytokeratin CAM5.2 and (E) synaptophysin in tumor cells. (F) Chromogranin A immunostaining is present in some cells, with faint intensity. (G) Ki-67 labeling index is 80–90%.

A metastasis of SCNEC was suspected, and a thorough search for primary tumor was conducted: repeated dermatological assessment of inguinal region and left inferior limb showed no abnormalities; upper and lower endoscopic studies were normal; computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of neck, thorax, abdomen and pelvic region did not reveal any suspicious lesion; 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) study had no abnormal radiopharmaceutical uptake. Heterogeneous radiopharmaceutical hypercaptation at prostate topography on 68Ga DOTA-TOC PET was found (Q.SUVmax=7.5). In face of this finding, multiple prostate biopsies were performed, revealing bilateral atrophy and chronic inflammation, with no evidence of malignancy or prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Serum chromogranin A was 23ng/mL (RR<102), and every other hematological, biochemical, and immunological studies were normal. Chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or other adjuvant treatments were not performed. An active surveillance strategy was decided with patient agreement. He remains disease-free after a 40-month follow-up period. We opted, in a multidisciplinary team setting, to conduct follow-up with clinical and analytical evaluations, including inflammatory markers, and yearly CT/MRI imaging and 18F-FDG PET-CT scan.

Extrapulmonary small cell carcinoma are uncommon malignancies with a reported incidence between 2.5–5.0% of small cell carcinoma cases and 0.1–0.4% of all malignancies.1 They can occur in almost all sites of the body, mainly gastrointestinal and genitourinary systems.2 SCNEC usually present as aggressive high-grade tumors with dismal prognosis. Small cell carcinoma located exclusively in a lymph node or multiple lymph nodes without any evidence of a primary tumor are even rarer, our comprehensive literature review yielded less than 20 cases reported to date.

Lymph node SCNEC's origin is very peculiar since, in normal circumstances, neuroendocrine cells are absent from lymph nodes. It could arise from a multipotent stem cell or due to a primary cancer elsewhere in the body with secondary metastases to the lymph node and spontaneous regression of the primary lesion.

Everson and Cole first described, in 1956, spontaneous cancer regression.3 Should our patient's primary tumor had undergone spontaneous regression, diagnosis could have been established from the metastatic lesion. However, given the tumor's extremely high grade (Ki67 80–90%), it's likely that recurrence would have to become obvious after surgical resection.

Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC), an aggressive primary neuroendocrine malignancy of the skin, disseminates frequently to regional lymph nodes. MCC has also been found in inguinal lymph nodes in the absence of a primary site4. In our case, physical examination did not reveal any suspicious primary skin lesion and there was an absence of reactivity of malignant cells for cytokeratin 20, so a MCC is rather improbable.

Our first approach was to rule out an occult primary tumor. Exhaustive investigation was innocent and included clinical, analytical, and radiological evaluations, as well as functional exams (including 18F-FDG PET and a somatostatin receptor PET tracer). Also, after 40 months, our patient maintains an excellent general condition with a normal CT scan and absence of uptake in 18F-FDG PET.

The main difference between extrapulmonary SCNEC located in other organs compared with lymph node SCNEC seems to be the latter's better prognosis.5,6 Despite being a very rare entity, its identification is crucial because adequate treatment can lead to favorable clinical outcomes.

Although there's no standard treatment, several approaches have been proposed according to the site and stage of the tumor, the patient, and the physician. In the literature, surgery, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of these treatments remain the therapeutic options available.6 Immune checkpoint inhibitors were used with a favorable clinical response in other extrapulmonary SCNEC.7,8 Its’ efficacy in lymph node SCNEC is unknown.

Although surgical resection with curative intent combined with chemotherapy was proposed for lymph node SCNEC,6 some case reports demonstrate long-term disease-free survival in patients submitted solely to surgical resection, even with metastatic disease.9 This latter approach is only feasible if a close follow-up, with periodic 18F-FDG PET-CT scans, could be provided, in order to allow for early detection of recurrent or metastatic disease.

Although a 40-month period might appear somewhat short, the tumor's extremely high Ki67 index (80–90%) could lead to recurrence in over 3 years of follow-up. Studies show worse prognosis in neuroendocrine carcinomas with higher Ki67, including shorter overall survival for Ki67>55%.10

In conclusion, this case represents a very rare entity in which a more conservative approach, with simply surgical excision of lymph node SCNEC, lead to a favorable outcome.

Nonetheless, more evidence is needed to better understand lymph node SCNEC's natural history and to develop clinically oriented guidelines with optimal surveillance and therapeutic regimens.

Authors’ contributionsFSC drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical standardsWritten informed consent for publication was obtained.

FundingThis research received no funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the physicians who follow.