Mitochondrial diseases are a group of genetic disorders characterised by defects in oxidative phosphorylation and caused by mutations in genes in the nuclear DNA or mitochondrial DNA. Mitochondrial DNA mutations occur in 1 per 5000 adults and are transmitted through maternal inheritance.1 Diabetes is the most common endocrinopathy among mitochondrial disorders. Defects in the tricarboxylic acid cycle and electron transport chain lead to reduced oxidative phosphorylation, resulting in inefficient and suboptimal glucose-stimulated insulin secretion.1 Mitochondrial encephalomyopathy, lactic acidosis, stroke-like episodes (MELAS), and maternally inherited diabetes and deafness (MIDD) are the most common mitochondrial diabetes disorders,2 Although the m.3243A>G mtDNA pathogenic variant is more frequently linked to diabetes, other mutations can occur. Mitochondrial diabetes typically affects adults over 35 years, and most patients require insulin treatment a few years after its onset.3,4 The severity of diabetes has been strongly associated with increasing age, consistent with the clinical picture of a progressive disease.5 Hearing loss in MIDD frequently precedes the diagnosis of diabetes and tends to develop in early adulthood.6,7

To our knowledge, no studies exist on ultra-rapid insulin therapy in mitochondrial diabetes. Two cases of mitochondrial diabetes under basal-bolus insulin therapy with fast-acting insulin aspart will be discussed.

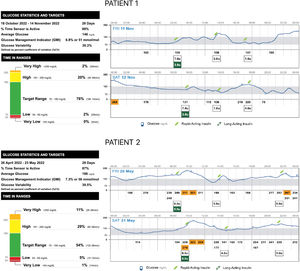

Patient 1 is a 50-year-old male with a chronic kidney disease known since childhood, and currently undergoing peritoneal dialysis and waiting for a kidney transplant. Notwithstanding occupational noise exposure, bilateral sensorineural hearing loss was identified in childhood. Diabetes was diagnosed during a routine evaluation when he was 30 years old (normal weight, c-peptide level 2.2ng/mL, and negative beta-cell antibodies), and insulin was started at diagnosis. To determine diabetes aetiology, he was submitted to genetic testing that revealed MT-TL1 mutation, m.3243A>G, 20% heteroplasmy in peripheral blood leucocyte DNA. He was on basal insulin alone for 17 years after his diabetes diagnosis. During this period, sitagliptin 25mg od was started. However, HbA1c levels started to rise to 7.5–8.0%, and the flash glucose monitoring device Freestyle Libre was employed, showing significant post-prandial hyperglycemia with insulin glargine U-100 9IU/day. He was then started on fast-acting insulin aspart before the three main meals, according to pre-prandial glucose levels. His basal insulin is now glargine U-100 3IU in the morning, and his daily insulin dose (TDI) is 10–15IU/d (0.15–0.23IU/kg/d). Glucose control has significantly improved, as shown by monitoring reports, and basal insulin needs are now less than 30% of TDI (Fig. 1). Apart from chronic kidney disease, no other target-organ diabetes complications were present years before the diabetes diagnosis. A family history of diabetes was present in Patient 1's mother and two siblings.

Patient 2 is a 56-year-old male with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss. A family history of hearing loss was present in the patient's mother and maternal aunt. Diabetes was diagnosed when he was 40 years old during routine evaluation (normal weight, c-peptide level 3.1ng/mL, and negative beta-cell antibodies), and insulin was started at diagnosis. Genetic testing revealed a variant in the MT-CO3 gene, m.9325T>C, p.(Met40Thr) in homoplasmy. Different basal-bolus regimens had been employed with inconsistent results. Due to HbA1c levels persistently over 8%, flash glucose monitoring Freestyle Libre was used. Due to significant post-prandial hyperglycemia, insulin glulisine was switched to fast-acting insulin aspart. Bolus insulin was adjusted, and basal insulin dosing was reduced to less than 30% of TDI (Fig. 1). Despite not achieving optimal glycemic control, ambulatory glucose profile reports have improved. Annual retinopathy screening was normal, and no other diabetes-related complications were known.

Management of mitochondrial diabetes is challenging, as there are no guidelines or clinically riented recommendations.

Due to the risk of lactic acidosis, metformin is usually contraindicated. It has also been proposed that metformin could trigger neurological manifestations in this condition.8 Sulfonylureas were traditionally viewed as first-line therapy in patients with MIDD. However, the risk of hypoglycemia with this therapy remains. DPP4-inhibitors are considered safe and well-tolerated in patients with MIDD.7 Patient 1 is being treated with sitagliptin.

Novel therapies, such as SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP-1 receptor agonists, have demonstrated clinical benefit in some case reports.9

In order to achieve reasonable glycemic control, both of our patients require basal-bolus insulin regimens. Compared with first-generation rapid-acting insulin analogues, ultra-rapid insulins have demonstrated benefits in post-prandial glycemic control in type 1 and type 2 diabetes.10 Since glucose-stimulated insulin secretion is impaired in mitochondrial diabetes, we have decided to use fast-acting insulin aspart to target post-prandial hyperglycemia more efficiently. Our results are satisfactory, as demonstrated by glucose monitoring reports.

Haemoglobin A1c has not been validated for diagnosis or follow-up of mitochondrial diabetes. Since these patients have significant post-prandial hyperglycemia, other methods of glycemic evaluation might be more suitable. We have opted for a flash glucose monitoring device for our patients, and the ambulatory glucose report has significantly impacted insulin therapy adjustment, with continuous reductions in basal insulin and bolus insulin.

The association of diabetes and sensorineural deafness must prompt an investigation of mitochondrial diabetes, especially if there is a maternal history of diabetes and/or deafness. This diagnosis will allow family screening, education, surveillance for future complications, and personalised care.

In a continuously evolving era in diabetes management, new strategies can also play a role in uncommon types of diabetes. As such, we propose that ultra-rapid insulin shall be considered in managing patients with mitochondrial diabetes when other strategies fail to achieve optimal glycemic control. Also, glucose monitoring devices can be employed to evaluate post-prandial glucose excursions and assist clinicians in decision-making.

Authors’ contributionsFSC drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in the critical revision of the manuscript and have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethical standardsWritten informed consent for publication was obtained.

FundingThis research received no funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors would like to thank all the physicians who followed our patient.