Hypoglycaemia is associated with long-term negative consequences in people with diabetes, such as an increase in glycaemic variability and a higher risk of mortality.1 A hypoglycaemic episode can involve acute symptoms, such as irritability, shakiness, tachycardia and confusion, which can progress to loss of consciousness, seizure, coma or death.1 Considering the unpleasant symptoms that can accompany hypoglycaemia and its potential short- and long-term risks, it can often lead to anxiety and fear in people with diabetes,2,3 leading to a reduction in their quality of life.2,4 Nocturnal hypoglycaemia is common in patients with diabetes, given that almost 50% of all episodes of severe hypoglycaemia occur during sleep.5 Thus, nocturnal hypoglycaemia can affect sleep quality.2,6

Considering that people might tend to search the Internet about a topic whenever it comes to their minds or worries them, we thought that people with diabetes worldwide would probably search more often for “hypoglycaemia” at the time of day when they have the most episodes, or whenever those episodes are severe enough to cause concern. These data could provide indirect insight into the hourly worldwide awareness of hypoglycaemia, as studies exploring the global interest in hypoglycaemia are lacking.

Google is undoubtedly the most popular Internet search engine. Google Trends is a tool Google developed in 2006 that can provide an analysis of the popularity of Google searches across various regions over time, showing the size of a term's search volume during every time period in the Internet's history. Mainly since 2020, Google Trends has been used by the scientific community to analyse social interest in various subjects, focusing particularly on the COVID-19 pandemic.7 To our knowledge, there are only a few Google Trends-based studies on diabetes,7–9 none of which have targeted hypoglycaemia.

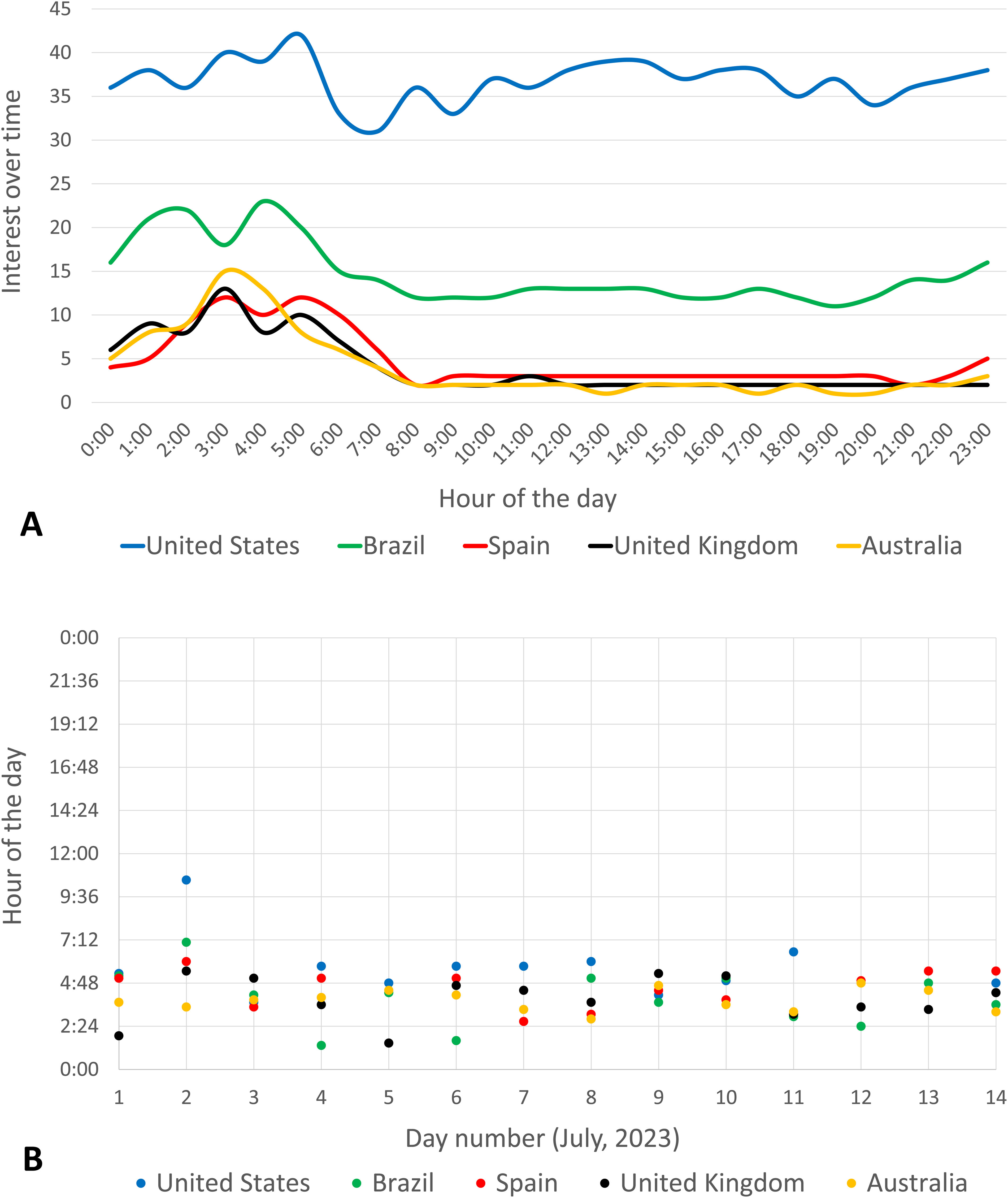

To analyse the time of day when the term “hypoglycaemia” was searched more frequently worldwide, we recorded day-by-day Google Trends data from five countries (United States, Brazil, Spain, United Kingdom and Australia) for 14 days (1–14 July 2023). So as to adapt this Google Trends search to the most spoken language of each country, the term was searched as “hypoglycemia” for the United States, as “hipoglicemia” for Brazil, as “hipoglucemia” for Spain, and as “hypoglycaemia” for the United Kingdom and Australia. Every search was adapted to each country's capital city time zone. Search data were obtained for each country every eight minutes for the 14 days of the study. This allowed us to calculate an hour-by-hour average Google interest in hypoglycaemia across these countries during this period (Fig. 1A). As the figure shows, the time of day when most of the Google searches for “hypoglycaemia” occurred was at night (especially from 3a.m. to 5a.m.), which was common to all the five countries studied. The average interest score from 0.00a.m. to 6.00a.m. (night-time) was higher than the average interest score from 6.01a.m. to 11.59p.m. (daytime) in each and every country (p<0.01 for every country, Student's t-test). The mean hourly night-time interest score for all the five countries combined (17 points) was higher than the mean hourly daytime score (11 points; p<0.001). The eight-minute time of day with the maximum searches in each country during each of these 14 days was also recorded, showing that the time of greatest interest in searching for hypoglycaemia was also at night (Fig. 1B). The same study was repeated two months later, with similar results (data not shown). Taken together, these results could reflect that the time of day with maximum interest in hypoglycaemia is at night, probably showing that people with diabetes tend to have more severe or worrying hypoglycaemic episodes at night, while sleeping.

Google Trends interest in hypoglycaemia. (A) (upper panel): mean Google Trends interest in hypoglycaemia during the day for 14 consecutive days in the five countries studied. Interest score, plotted on the y-axis, does not represent an absolute volume of number of searches. For every time period, Google Trends presents data normalised on a scale from 0 to 100 points. The eight-minute period of greatest interest each day is given 100 points. The rest of the day's points are calculated by taking the time of greatest interest as a reference. For instance, if the time of greatest interest one day (100 points) got 10 Google searches, an eight-minute period at which Google received five searches would be given 50 points. Therefore, eight-minute periods with 0 searches are given 0 points. In this context, the interest score is usually directly proportional to the number of searches, which is also directly proportional to the population of each country. (B) (lower panel): dots represent the time of day with the maximum searches for every country in each of the 14 days.

The study has limitations to be acknowledged. In general, infodemiology studies are mainly conceived as hypothesis generators. We cannot guarantee that the reason a person is searching Google for hypoglycaemia is because they have diabetes or are experiencing a hypoglycaemic episode. Moreover, the entire population is not fully represented, given that some people might use other search engines and some do not have access to the Internet. Neither Asian nor African countries were included due to their non-use of the Latin alphabet or little use of Google. Finally, the peak search time can be the one generally used, and it may be not restricted to hypoglycaemia. As a control, however, it can be observed that, when searching the words “breakfast”, “lunch” and “dinner” in the United States in Google Trends, the graphs displayed show that these words are searched more often at approximately 9a.m., 12p.m. and 6p.m., respectively (Supplementary Figure 1).

Understanding patients’ feelings is an important aspect of managing diabetes.2 Fear of hypoglycaemia at night is a particular concern.2,4–6 The data from the present study confirm the specific interest of the population in nocturnal hypoglycaemia. Understanding the complex interplay of emotions concerning hypoglycaemia can guide healthcare providers in improving clinical practice.2

FundingThis project was conducted without any financial support.

Conflicts of interestNone to declare.