The development of pseudoaneurysms of the internal carotid artery (pICA) is a vascular complication of endoscopic endonasal transsphenoidal (EET) surgery, with an incidence of 0.55–2%.1,2 These are lesions composed solely of the adventitial layer of blood vessels.1 Lack of adequate treatment can result in devastating consequences, due to the risk of rapid growth and rupture, with a mortality rate of 30–50%.1–4 Although therapeutic management of pICA is complex, there are multiple surgical and endovascular techniques available.1,2

We present the case of a 71-year-old woman with an incidental diagnosis of acromegaly associated with a Knosp grade 1 pituitary macroadenoma (1.3 × 1.1 × 1.4 cm), with suprasellar extension and contact with the optic chiasm. The patient had no hormonal abnormalities except for increased IGF-1. She was treated by Doppler-assisted EET surgery, with reaming of the sella turcica to expose both cavernous sinuses (CS), without uncovering of the carotids or opening of the CS. Macroscopically complete excision of the soft lesion was achieved, with no special manipulation of the lateral borders or carotid arteries required. No CSF fistula was identified. Multilayer closure was performed, without requiring nasal packing.

In the immediate postoperative period (p.o.) the patient developed nasal bleeding after sneezing, requiring anterior nasal packing, which was removed 48 h later. The patient progressed well and was discharged four days after the procedure. Ten days later she had new episodes of epistaxis in the context of hypertension. An urgent surgical review was performed, cauterising slight bleeding in the rescue flap and in the right upper turbinate.

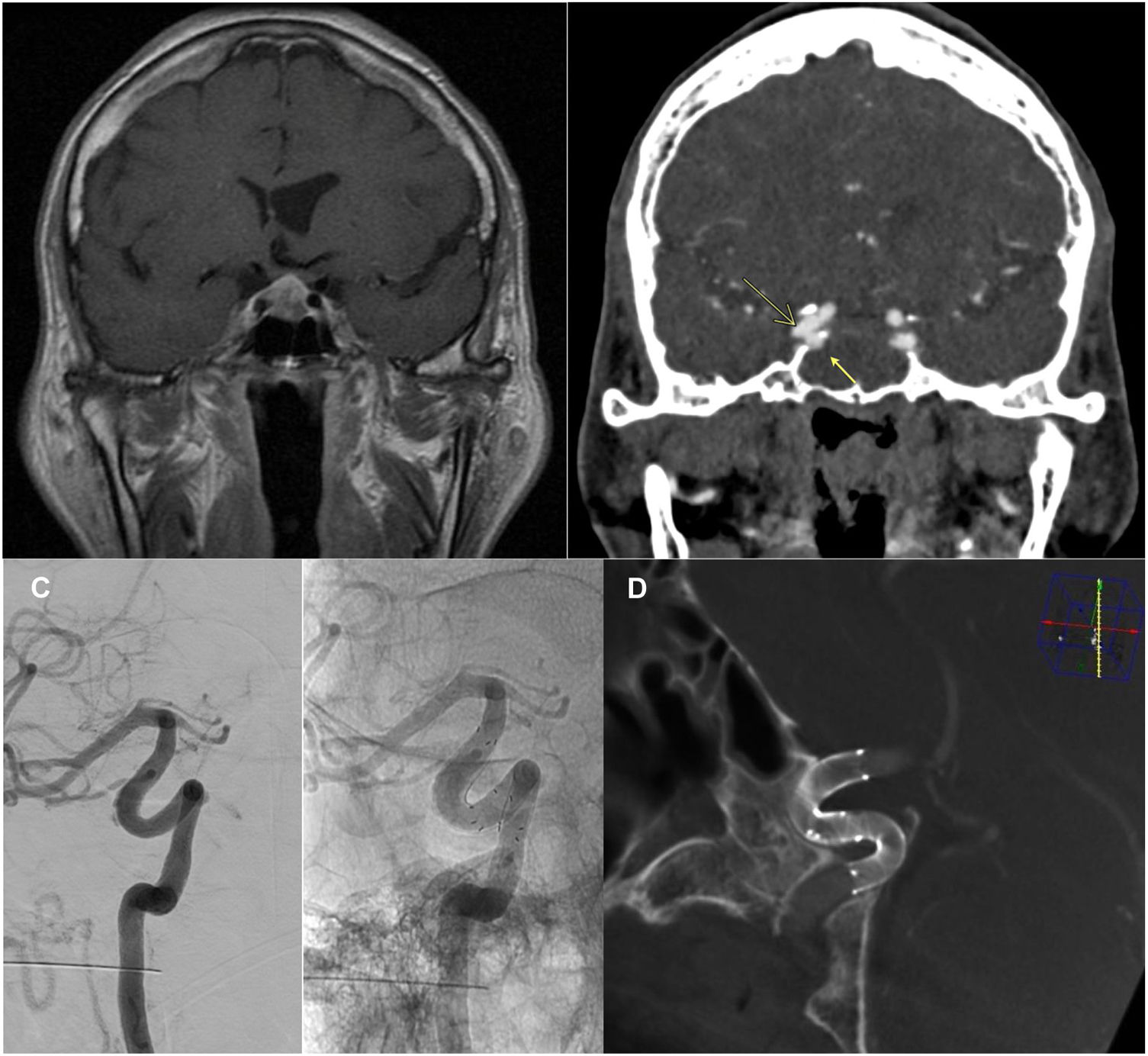

Despite that, three days later the patient had further episodes of epistaxis, which led to another surgical review and, in the absence of bleeding as a cause, to emergency CT-angiogram (Fig. 1A) and subsequent cerebral angiography (Fig. 1B). Two images were found to be consistent with pseudoaneurysms of the right internal carotid artery. They were treated by micro-catheterisation of the right internal carotid artery distal to the aneurysmal lesions and implantation of two overlapping Derivo® flow diverter stents covering the neck of both lesions, without incident and without complications. The patient was discharged after 48 h of observation with dual antiplatelet therapy (ticagrelor 90 mg/12 h and ASA 100 mg/24 h), without further complications. Follow-up at six and 15 months confirmed stent patency and resolution of the pICA, with persistent filling of the neck of the cavernous segment, without significant hyperplasia or other complications (Figs. 1C and 1D), and the ticagrelor treatment was discontinued. The patient's IGF-1 levels are currently stable within the normal range.

Pituitary macroadenoma seen on preoperative MRI (A), contrast-enhanced T1-weighted sequence. Diagnostic CT-angio (B) 20 days p.o. Two wide-necked, blister-like pICA (arrows) are identified in the cavernous (medial, 3.5 mm neck and 2.5 mm depth, adjacent to the pituitary gland) and clinoid (bilobar, lateral, 3 and 2.5 mm depth, respectively) segments of the right ICA, which were also studied by angiography. C and D) Repeat angiography at six months (C) and follow-up DynaCT® at 15 months (D) after endovascular treatment with implantation of two overlapping Derivo® flow diverter stents. Stent patency and resolution of pICA confirmed, with patency of the carrier artery and no signs of stenosis or other intra-stent abnormalities.

As occurred with the medial pICA in the case reported here, the most commonly affected segment is the cavernous segment.4 Even when there is good intraoperative haemostasis and no suspicion of carotid injury, delayed lesions such as pICA or carotid-cavernous fistulae can occur.3,5,6 Management is complex, and a lack of adequate treatment can have devastating consequences, including death.1,6 Clinical series report a pICA rupture rate of up to 60%.1

If vascular injury is suspected, an immediate angiographic study should be performed and, if negative, repeated after one week to identify possible delayed formation of pICA.3,4,7 Presentation with observed delayed epistaxis is described in the literature, with an incidence of 0.6–3.3 % (1–3 weeks after surgery).6,8

Risk factors for vascular injury during EET surgery are anatomical bone and vascular variants, displacement of the ICA by the lesion itself or reduced intercarotid space, invasion of the CS by the lesion, previous surgical or radiotherapy treatments and expanded approaches to more complex lesions.1,4,7,9

In this case, it was interesting that one of the pICA is located laterally, not directly in contact with the surgical site. Endothelial dysfunction has been described in patients with acromegaly due to structural and functional changes that make the vessels stiffer and less elastic9, a factor which could explain the development of acromegaly, possibly due to indirect damage. A higher incidence of dolichoectasia and protrusions in ICA (35–53%), asymmetry in their trajectory and a higher incidence of cerebral aneurysms (at any location) than the general population (2–18% vs. 0.8–1.3%) are described.9,10 At the bony level, there may be a lack of wall around the ICA ("carotid dehiscence", in 22.2% of cases with acromegaly vs 6.6%). Bone remodelling in these cases is related to a smaller intercarotid distance at the C3-segment.9,10 This is associated with an increased surgical risk in terms of possible ICA injury.9,10

The best management of ICA lesions is prevention, thanks to our understanding of the risk factors, and to take them into consideration when the case is studied in the preoperative MRI. In terms of treatment, more and more cases are described in which the vessel can be preserved thanks to current treatment techniques, as in our case, allowing embolisation or endovascular reconstruction.5,7 The treatment of choice is endovascular,1–3 as it is less invasive and has lower morbidity rates.

Treatment with flow diverter stents is usually the first choice as it has similar effectiveness to other endovascular techniques and fewer complications.2,3 The alternative is arterial occlusion using coils or a balloon.3 Surgical treatment should be performed in cases of significant mass effect, or as rescue in cases where endovascular treatment is ineffective.1

The favourable outcome in our patient after treatment was as would be expected according to the literature: in a review of 3,658 patients treated by EET surgery with 20 cases of ICA injury, 19 out of 20 had good recovery after endovascular treatment (six with stenting, five with arterial occlusion, 10 of them due to pICA) or packing (nine patients).3 At the one-month follow-up, the angiogram showed complete resolution of the ICA lesions.3 At subsequent follow-up (4–10 months) one patient had a modified Rankin Score (mRS) of 0, five patients an mRS of one and three patients an mRS of 2.3 Other series also describe favourable short- and long-term neurological outcomes after treatment of ICA lesions.7

Therefore, although uncommon, iatrogenic ICA injuries in EET surgery can have devastating consequences. In the case of suspected pICA, even with delayed symptoms, an immediate angiographic study should be performed and endovascular treatment considered. Acromegaly is a significant surgical risk factor.