To assess the effect of the 2019 coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on gestational diabetes (GDM).

Material and methodsIn this retrospective, multicentre, non-interventional study carried out in Castilla-La Mancha, Spain, we compared 663 women with GDM exposed to the pandemic (pandemic group), with 622 women with GDM seen one year earlier (pre-pandemic group). The primary endpoint was a Large for Gestational Age (LGA) newborn as an indicator of poor GDM control. Secondary endpoints included obstetric and neonatal complications.

ResultsDuring the pandemic, the gestational week at diagnosis (24.2 ± 7.4 vs 22.9 ± 7.7, p = 0.0016) and first visit to Endocrinology (26.6 ± 7.2 vs 25.3 ± 7.6, p = 0.0014) were earlier. Face-to-face consultations were maintained in most cases (80.3%). The new diagnostic criteria for GDM were used in only 3% of cases. However, in the pandemic group, the final HbA1c was higher (5.2 ± 0.48 vs 5.29 ± 0.44%, p = 0.047) and there were more LGA newborns (8.5% vs 12.8%, p = 0.015). There were no differences in perinatal complications.

ConclusionsCare for GDM in our Public Health System did not significantly deteriorate during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this did not prevent a higher number of LGA newborns.

Evaluar el efecto de la pandemia por coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) sobre la diabetes gestacional (DMG).

Material y métodosEn este estudio observacional, multicéntrico y retrospectivo llevado a cabo en Castilla-La Mancha, España, comparamos 663 mujeres con DMG expuestas a la pandemia (grupo pandemia) con 622 atendidas un año antes (grupo prepandemia). La variable principal fue un recién nacido grande para la edad gestacional (GEG) como indicador de mal control de la DMG. Como variables secundarias se incluyeron las complicaciones obstétricas y neonatales.

ResultadosDurante la pandemia, la semana gestacional al diagnóstico (24,2 ± 7,4 vs. 22,9 ± 7,7; p = 0,0016) y a la primera visita a Endocrinología (26,6 ± 7,2 vs. 25,3 ± 7,6; p = 0,0014) fueron más precoces. Las consultas presenciales se mantuvieron en la mayoría de los casos (80,3%). Los nuevos criterios diagnósticos de DMG solo se utilizaron en 3%. Sin embargo, en el grupo pandemia la hemoglobina glicosilada (HbA1c) final fue más alta (5,2 ± 0,48 vs. 5,29 ± 0,44%, p = 0,047) y hubo más recién nacidos GEG (8,5 vs. 12,8%, p = 0,015). No existieron diferencias en complicaciones perinatales.

ConclusionesLa atención a la DMG en nuestro Sistema Público de Salud no sufrió un deterioro importante durante la pandemia por COVID-19, sin embargo, ello no evitó un mayor número de recién nacidos GEG.

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, health services have been forced to implement strategies aimed at mitigating its negative effects.1,2 Healthcare activity is being affected by the measures introduced to try to contain the pandemic. Telemedicine has been one of the most widely used tools.3,4 While a large number of disorders in our speciality have been managed electronically, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) has continued to be treated in person in many cases, taking advantage of the patients’ obstetrics check-ups. It is unknown whether pregnant women are more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection.5

GDM is the metabolic disorder most commonly associated with pregnancy, affecting approximately 12% of pregnant women.6,7 Diabetic patients are more susceptible to developing severe forms of SARS-CoV-2 infection,8 which is why various scientific societies have developed temporary alternatives for the diagnosis and monitoring of gestational hyperglycaemia during the COVID-19 pandemic, in order to minimise the risk of infection.9–15

Our hypothesis is that the control of patients with GDM has worsened during the pandemic, not only due to the pressure of care borne by the public health service and the consequent changes in routine clinical practice, but also due to the decrease in physical activity, changes in eating habits and the stress to which pregnant women have been subjected.16,17

The aim of our study was to determine whether or not the COVID-19 pandemic increased the risk of having “large for gestational age” (LGE) newborns, as an indicator of poor control of patients with GDM treated in the public health service of Castilla-La Mancha Autonomous Region (Spain) and, as secondary endpoints, maternal and neonatal morbidity rates.

Material and methodsStudy designWe carried out a multicentre, retrospective, observational study in 11 Endocrinology and Nutrition Departments, which come under the Servicio de Salud de Castilla-La Mancha (SESCAM) [Castilla-La Mancha Autonomous Region Health Service] in Spain. We compared pregnant women with GDM kept under follow-up by this department in two periods, one running from the beginning of the lock-down decreed by the Government of Spain on 15 March 2020 until 14 March 2021 (pandemic group) and the other comprising the same period of the previous year (pre-pandemic group). The inclusion criterion was the date of the first consultation at the Endocrinology Department.

During the pandemic we followed the recommendations of the Grupo Español de Diabetes y Embarazo (GEDE) [Spanish Diabetes and Pregnancy Group],9 which proposed maintaining, as far as possible, the two-step diagnostic procedure for GDM in accordance with the criteria of the National Diabetes Data Group (NDDG)18:

- –

Universal screening using oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) with 50 g (O’Sullivan test) in the second trimester, at 24–28 weeks of gestation (except in case of risk factors, as it was done in the first trimester).

- –

OGTT with 100 g in those cases in which the O’Sullivan test was positive (≥140 mg/dl), using 105 mg/dl as a threshold for the diagnosis of GDM for fasting glucose and 190 mg/dl, 165 mg/dl and 145 mg/dl at 60, 120 and 180 min respectively. The diagnosis of GDM was made when glucose reached or exceeded these levels at two or more of the time points.

However, in order to minimise the risk of contagion, the possibility of an alternative diagnosis was suggested:

- –

First trimester: using glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) ≥5.9% combined with a preferably random determination of plasma glucose ≥165–199 mg/dl or, failing that, basal ≥100 mg/dl.

- –

Second trimester: using HbA1c ≥5.7% combined with a preferably random determination of plasma glucose ≥165–199 mg/dl or, failing that, basal ≥95 mg/dl. To make the diagnosis it would be enough to meet one of the criteria.

In the pandemic situation, the GEDE establishes that an O'Sullivan test ≥200 mg/dl can be considered a diagnosis of GDM.

Data collectionWe collected all cases treated during the above-cited periods, excluding patients who were not located for follow-up. The data were taken from the electronic medical records by diabetologists from the above-mentioned departments.

The primary endpoint was an LGA newborn, the data taken from the Paediatric discharge report, and the secondary endpoint consisted of obstetric and neonatal complications, considering the COVID-19 pandemic as the exposure variable. In addition to the sociodemographic variables, we recorded dates (last period, GDM diagnosis, first visit to Endocrinology, childbirth), clinical variables (family history of diabetes, obstetric history, GDM diagnostic procedure, weight before pregnancy and at the end of pregnancy, insulin treatment, weight of the newborn), analytical tests (O’Sullivan test, OGTT with 100 g, basal plasma glucose for the diagnosis of GDM according to the new temporary criteria recommended during the pandemic, HbA1c for diagnosis according to the same criteria, final HbA1c) and complications (preeclampsia, hypertension [HTN], type of delivery, perinatal complications, SARS-CoV-2 infection).

Statistical analysisAfter the descriptive analysis, a univariate model was developed which included the characteristics of the patients and the outcomes of the pregnancies, as well as a logistic regression model for the primary endpoint (LGA). Qualitative variables of frequency were expressed in terms of percentages and quantitative variables were expressed in terms of mean ± SD. In the univariate analysis, the Student t test was used to compare the quantitative variables and the X2 test for the qualitative variables (in some cases Fisher’s F test). Statistical significance was considered when p values were <0.05. For statistical analysis, the STATA package version 14.2 (StataCorp LLC, Texas, USA) was used.

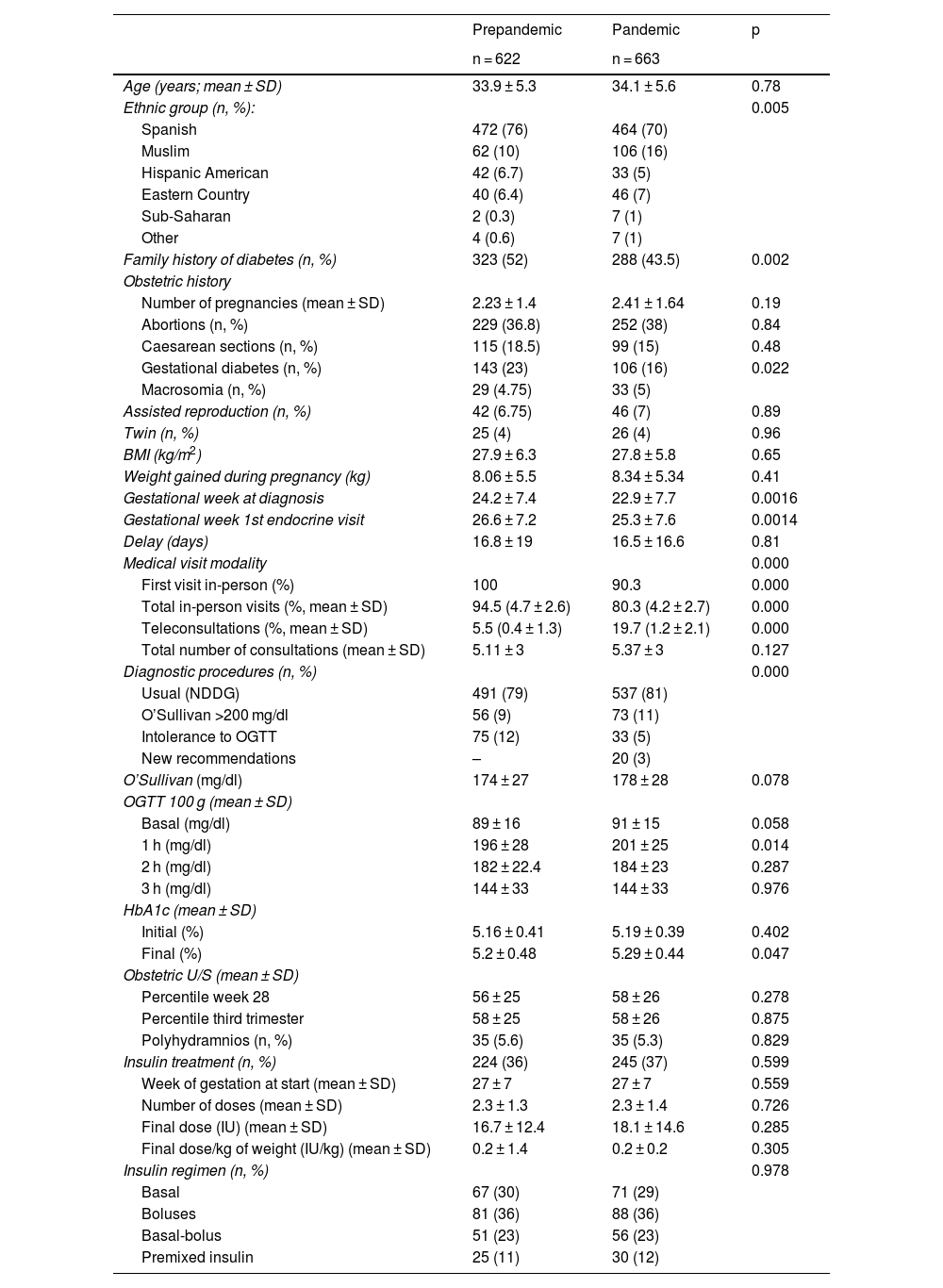

ResultsCharacteristics of the study populationA total of 1285 women diagnosed with GDM were included, 622 in the pre-pandemic group and 663 in the pandemic group (Table 1). Significant differences were observed in ethnic group (p = 0.005) mainly involving a lower percentage of Spanish women during the pandemic and more pregnant women of Muslim origin in the same period. Variations were also observed in family history of diabetes (52% vs 43.5%, p = 0.002) and in obstetrics history, having had GDM in previous pregnancies (23% vs 16%, p = 0.022), which were significantly lower in the pandemic group.

Comparison of the prepandemic and pandemic groups: sociodemographic, date-related, clinical and analytical variables.

| Prepandemic | Pandemic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 622 | n = 663 | ||

| Age (years; mean ± SD) | 33.9 ± 5.3 | 34.1 ± 5.6 | 0.78 |

| Ethnic group (n, %): | 0.005 | ||

| Spanish | 472 (76) | 464 (70) | |

| Muslim | 62 (10) | 106 (16) | |

| Hispanic American | 42 (6.7) | 33 (5) | |

| Eastern Country | 40 (6.4) | 46 (7) | |

| Sub-Saharan | 2 (0.3) | 7 (1) | |

| Other | 4 (0.6) | 7 (1) | |

| Family history of diabetes (n, %) | 323 (52) | 288 (43.5) | 0.002 |

| Obstetric history | |||

| Number of pregnancies (mean ± SD) | 2.23 ± 1.4 | 2.41 ± 1.64 | 0.19 |

| Abortions (n, %) | 229 (36.8) | 252 (38) | 0.84 |

| Caesarean sections (n, %) | 115 (18.5) | 99 (15) | 0.48 |

| Gestational diabetes (n, %) | 143 (23) | 106 (16) | 0.022 |

| Macrosomia (n, %) | 29 (4.75) | 33 (5) | |

| Assisted reproduction (n, %) | 42 (6.75) | 46 (7) | 0.89 |

| Twin (n, %) | 25 (4) | 26 (4) | 0.96 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.9 ± 6.3 | 27.8 ± 5.8 | 0.65 |

| Weight gained during pregnancy (kg) | 8.06 ± 5.5 | 8.34 ± 5.34 | 0.41 |

| Gestational week at diagnosis | 24.2 ± 7.4 | 22.9 ± 7.7 | 0.0016 |

| Gestational week 1st endocrine visit | 26.6 ± 7.2 | 25.3 ± 7.6 | 0.0014 |

| Delay (days) | 16.8 ± 19 | 16.5 ± 16.6 | 0.81 |

| Medical visit modality | 0.000 | ||

| First visit in-person (%) | 100 | 90.3 | 0.000 |

| Total in-person visits (%, mean ± SD) | 94.5 (4.7 ± 2.6) | 80.3 (4.2 ± 2.7) | 0.000 |

| Teleconsultations (%, mean ± SD) | 5.5 (0.4 ± 1.3) | 19.7 (1.2 ± 2.1) | 0.000 |

| Total number of consultations (mean ± SD) | 5.11 ± 3 | 5.37 ± 3 | 0.127 |

| Diagnostic procedures (n, %) | 0.000 | ||

| Usual (NDDG) | 491 (79) | 537 (81) | |

| O’Sullivan >200 mg/dl | 56 (9) | 73 (11) | |

| Intolerance to OGTT | 75 (12) | 33 (5) | |

| New recommendations | – | 20 (3) | |

| O’Sullivan (mg/dl) | 174 ± 27 | 178 ± 28 | 0.078 |

| OGTT 100 g (mean ± SD) | |||

| Basal (mg/dl) | 89 ± 16 | 91 ± 15 | 0.058 |

| 1 h (mg/dl) | 196 ± 28 | 201 ± 25 | 0.014 |

| 2 h (mg/dl) | 182 ± 22.4 | 184 ± 23 | 0.287 |

| 3 h (mg/dl) | 144 ± 33 | 144 ± 33 | 0.976 |

| HbA1c (mean ± SD) | |||

| Initial (%) | 5.16 ± 0.41 | 5.19 ± 0.39 | 0.402 |

| Final (%) | 5.2 ± 0.48 | 5.29 ± 0.44 | 0.047 |

| Obstetric U/S (mean ± SD) | |||

| Percentile week 28 | 56 ± 25 | 58 ± 26 | 0.278 |

| Percentile third trimester | 58 ± 25 | 58 ± 26 | 0.875 |

| Polyhydramnios (n, %) | 35 (5.6) | 35 (5.3) | 0.829 |

| Insulin treatment (n, %) | 224 (36) | 245 (37) | 0.599 |

| Week of gestation at start (mean ± SD) | 27 ± 7 | 27 ± 7 | 0.559 |

| Number of doses (mean ± SD) | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 2.3 ± 1.4 | 0.726 |

| Final dose (IU) (mean ± SD) | 16.7 ± 12.4 | 18.1 ± 14.6 | 0.285 |

| Final dose/kg of weight (IU/kg) (mean ± SD) | 0.2 ± 1.4 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.305 |

| Insulin regimen (n, %) | 0.978 | ||

| Basal | 67 (30) | 71 (29) | |

| Boluses | 81 (36) | 88 (36) | |

| Basal-bolus | 51 (23) | 56 (23) | |

| Premixed insulin | 25 (11) | 30 (12) |

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or n (%); comparisons between groups were made using the X2 test, Fisher’s F test or Student’s t test; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (values highlighted in bold in the table).

BMI: body mass index; HbA1c: glycosylated haemoglobin; NDDG: National Diabetes Data Group; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test; U/S: ultrasound.

It should be noted that both the gestational week at diagnosis (24.2 ± 7.4 vs 22.9 ± 7.7; p = 0.0016) and the first visit to the Endocrinology clinic (26.6 ± 7.2 vs 25.3 ± 7.6; p = 0.0014) were earlier during the pandemic, although there was no difference in the days of delay between them (16.8 ± 19 vs 16.5 ± 16.6; p = 0.81).

Face-to-face consultation was largely maintained (80.3%) during the pandemic. The diagnosis of GDM using the new recommended criteria was only used in 3% of the pregnant women who were detected in said period, with the usual two-step procedure (NDDG) prevailing in both groups (79% vs 81%). The final HbA1c was slightly higher in the pandemic group (5.2 ± 0.48 vs 5.29 ± 0.44%, p = 0.047).

Regarding the need for insulin treatment for adequate blood glucose control, no differences were found between the two groups.

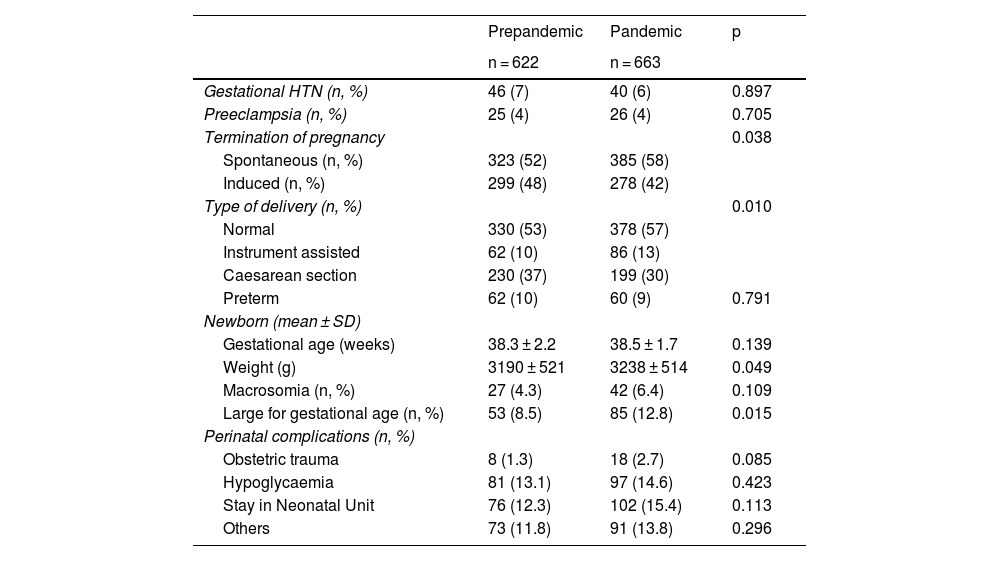

Pregnancy outcomesThe univariate analysis regarding obstetrics results is shown in Table 2. There was no difference in gestational age at birth between the two groups (38.3 ± 2 vs 38.5 ± 1.7; p = 0.139). In the pandemic group, a greater number of pregnancies ended spontaneously (52% vs 58%) and there were more normal deliveries (53% vs 57%) and instrument-assisted deliveries (10% vs 13%) compared to Caesarean sections, which were performed more frequently in the pre-pandemic group (37% vs 30%). For the newborns, they had a slightly higher weight in the pandemic group (3,190 ± 521 vs 3,238 ± 514, p = 0.049) and there were more LGA newborns (8.5% vs 12.8%, p = 0.015). However, there were no differences in perinatal complications such as obstetric trauma, hypoglycaemia or stay in the Neonatology Unit.

Comparison of the prepandemic and pandemic groups: pregnancy complications, birth characteristics, data on newborn, perinatal difficulties.

| Prepandemic | Pandemic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n = 622 | n = 663 | ||

| Gestational HTN (n, %) | 46 (7) | 40 (6) | 0.897 |

| Preeclampsia (n, %) | 25 (4) | 26 (4) | 0.705 |

| Termination of pregnancy | 0.038 | ||

| Spontaneous (n, %) | 323 (52) | 385 (58) | |

| Induced (n, %) | 299 (48) | 278 (42) | |

| Type of delivery (n, %) | 0.010 | ||

| Normal | 330 (53) | 378 (57) | |

| Instrument assisted | 62 (10) | 86 (13) | |

| Caesarean section | 230 (37) | 199 (30) | |

| Preterm | 62 (10) | 60 (9) | 0.791 |

| Newborn (mean ± SD) | |||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.3 ± 2.2 | 38.5 ± 1.7 | 0.139 |

| Weight (g) | 3190 ± 521 | 3238 ± 514 | 0.049 |

| Macrosomia (n, %) | 27 (4.3) | 42 (6.4) | 0.109 |

| Large for gestational age (n, %) | 53 (8.5) | 85 (12.8) | 0.015 |

| Perinatal complications (n, %) | |||

| Obstetric trauma | 8 (1.3) | 18 (2.7) | 0.085 |

| Hypoglycaemia | 81 (13.1) | 97 (14.6) | 0.423 |

| Stay in Neonatal Unit | 76 (12.3) | 102 (15.4) | 0.113 |

| Others | 73 (11.8) | 91 (13.8) | 0.296 |

The results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or n (%); comparisons between groups were made using the X2 test, Fisher’s F test or Student’s t test; p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant (values highlighted in bold in the table).

HTN: hypertension.

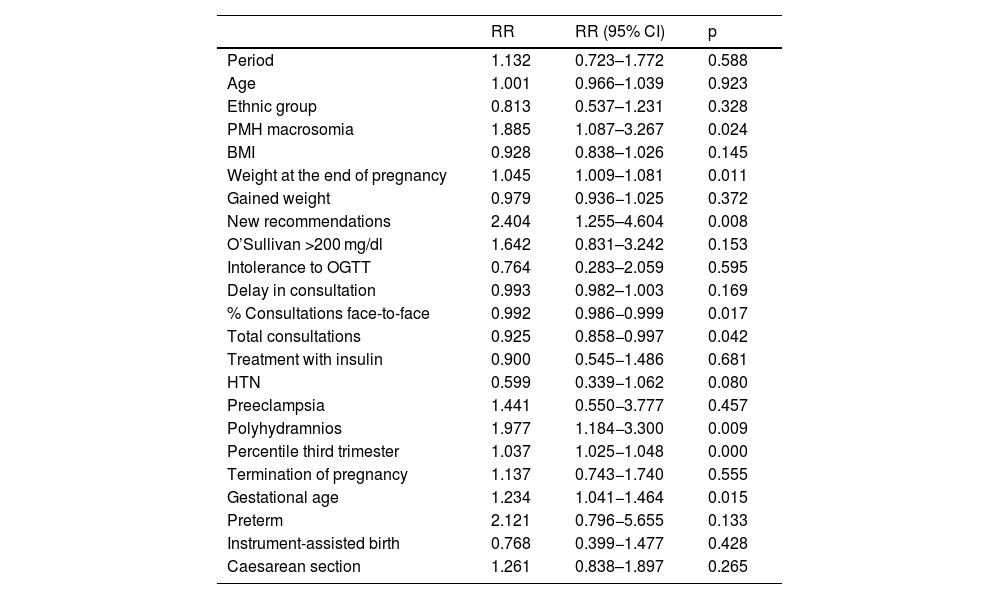

A multivariate logistic regression model was developed considering the dichotomous variable newborn LGA as dependent and, as independent variables, age, those which showed significance <0.05 in the univariate analysis or which could be related from a point of view of biological plausibility (Table 3). Among the variables introduced into the model, the “diagnostic procedure according to the new recommendations” is important, both for its clinically relevant effect and for its statistical significance. It was found that newborns of mothers diagnosed with GDM using the new guidelines, despite a relatively low sample size, had a statistically significant increased risk (relative risk [RR] = 2.40, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.255–4.604; p = 0.008) of being LGA (pseudo R2 = 0.19) at the time of delivery. Similarly, an increase in the RR of having LGA newborns was found in those who had a previous history of having had macrosomic children (RR = 1.88, 95% CI 1.087–3.267), those with greater weight at the end of pregnancy (RR = 1.045, 95% CI 1.009–1.081) and those who suffered from polyhydramnios (RR = 1.977, 95% CI 1.184–3.300). A decrease in the RR of having LGA newborns was found in mothers who attended a greater number of endocrinology consultations (RR 0.925, 95% CI 0.858–0.997) and in those in whom these consultations had been face-to-face (RR 0.992, 95% CI 0.986–0.999).

Multivariate model. Logistic regression for the variable large for gestational age.

| RR | RR (95% CI) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Period | 1.132 | 0.723–1.772 | 0.588 |

| Age | 1.001 | 0.966–1.039 | 0.923 |

| Ethnic group | 0.813 | 0.537–1.231 | 0.328 |

| PMH macrosomia | 1.885 | 1.087–3.267 | 0.024 |

| BMI | 0.928 | 0.838–1.026 | 0.145 |

| Weight at the end of pregnancy | 1.045 | 1.009–1.081 | 0.011 |

| Gained weight | 0.979 | 0.936−1.025 | 0.372 |

| New recommendations | 2.404 | 1.255–4.604 | 0.008 |

| O’Sullivan >200 mg/dl | 1.642 | 0.831–3.242 | 0.153 |

| Intolerance to OGTT | 0.764 | 0.283–2.059 | 0.595 |

| Delay in consultation | 0.993 | 0.982–1.003 | 0.169 |

| % Consultations face-to-face | 0.992 | 0.986−0.999 | 0.017 |

| Total consultations | 0.925 | 0.858−0.997 | 0.042 |

| Treatment with insulin | 0.900 | 0.545−1.486 | 0.681 |

| HTN | 0.599 | 0.339−1.062 | 0.080 |

| Preeclampsia | 1.441 | 0.550−3.777 | 0.457 |

| Polyhydramnios | 1.977 | 1.184−3.300 | 0.009 |

| Percentile third trimester | 1.037 | 1.025−1.048 | 0.000 |

| Termination of pregnancy | 1.137 | 0.743−1.740 | 0.555 |

| Gestational age | 1.234 | 1.041−1.464 | 0.015 |

| Preterm | 2.121 | 0.796−5.655 | 0.133 |

| Instrument-assisted birth | 0.768 | 0.399−1.477 | 0.428 |

| Caesarean section | 1.261 | 0.838–1.897 | 0.265 |

BMI: body mass index; HTN: hypertension; OGTT: oral glucose tolerance test; PMH: previous medical history.

Bold: statistically significant values.

Our results indicate that during the pandemic there was a greater number of LGA newborns, this being a criterion of worse control of GDM, despite the fact that the patients received similar healthcare.

In their retrospective study at a centre in Lille (France), Ghesquière et al. also found no differences in the follow-up of their patients, although their blood glucose control was worse in terms of postprandial blood glucose and the need for therapy with insulin.19 In our study we did not observe variations between the two groups in the analytical parameters collected, with the exception of the result for the OGTT with 100 g at the first hour and the final HbA1c, which were higher in the pandemic group, the latter reaching statistical significance. The need for insulin treatment was similar in both groups. We did not collect other control parameters, such as postprandial capillary blood glucose or time in target ranges, because it was a retrospective study and such information was not available in the medical records.

Various scientific societies published temporary recommendations for the diagnosis of GDM and its follow-up during the COVID-19 pandemic.9–15 The objective in all cases was to minimise face-to-face visits and reinforce telematics. In the first months of the pandemic, Justman et al. found a significant decrease in the number of visits by pregnant women to the Obstetrics and Gynaecology Department.20 We did not find a significant reduction in the total number of visits during the pandemic period studied compared to the previous year which, as they suggest, could be explained by the fact that these were pregnant women with GDM. Furthermore, in our study, more frequent and face-to-face monitoring acted as a protective factor against having an LGA newborn. Logically, we had a greater number of teleconsultations in the pandemic group, although the face-to-face mode was maintained at a rate that was probably higher than expected, despite which, only 53 (8%) patients in this group suffered SARS-CoV-2 infection, 65.4% of them asymptomatically. Four people required admission to the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) and treatment with corticosteroids due to serious complications related to the infection. Of all the variables studied in these women, we only found a significant difference in a greater weight at the end of pregnancy in those infected by SARS-CoV-2 (80.9 ± 14.9 vs 86.3 ± 17.1; p = 0.034), in accordance with epidemiological evidence that points to obesity as a risk factor for COVID-19.5,21 As in the cohort of the multicentre observational study of Spanish hospitals of the GESNEO-COVID research project,22 vertical transmission was not diagnosed in any of our cases.

In our population, the new GEDE recommendations were only used in 3% of pregnant women in the pandemic group, at the times of highest incidence of COVID-19, maintaining the usual diagnostic protocol in 81% of the women in this group. Curiously, the diagnosis of GDM and the first visit to Endocrinology took place earlier in the pandemic group. Some authors consider that the proposal to replace OGTT with the measurement of HbA1c and fasting plasma glucose in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic has a low sensitivity for detecting GDM. Furthermore, it does not appear to select women with the highest rate of adverse events during pregnancy.23 From our study we cannot infer a lower sensitivity of the new GEDE recommendations since the patients were not randomised to be diagnosed with one of the two methods. However, they would help identify those who are going to have a LGA newborn.

Other variables not collected, such as changes in lifestyle or a higher level of stress, could also justify our results, as well as the higher HbA1c at the end of pregnancy in the pandemic group. Ceulemans et al. found high levels of depressive symptoms and anxiety among pregnant women during the pandemic, which underlines the importance of monitoring perinatal mental health during this and other social crises.17 In an online survey of pregnant women with GDM in the United Kingdom, Hillyard et al. found that compliance with physical activity recommendations during the pandemic decreased by 50% compared to the previous period.16 In our study we did not collect information on physical activity, although the mobility restrictions suffered during the state of alarm decreed in Spain on 14 March 2020 and the subsequent conditions during the pandemic did not lead to greater weight gain in these women. This is in contrast to the report from Molina-Vega et al., who found that, although not statistically significant, there was greater weight gain in the 2020 group compared to the 2019 group,24 and the trial by the Sociedad Española para el Estudio de la Obesidad [Spanish Society for the Study of Obesity] in which the lockdown caused by the COVID-19 pandemic led to moderate weight gain in almost half of the Spanish population.25

Spontaneous and normal childbirth was significantly more common in the pandemic group, with fewer Caesarean sections, unlike reports from other authors who found no variations in this practice.20,26 The gestational age at the time of delivery was similar in both groups, as were the preterm births. Other perinatal complications such as obstetric trauma, hypoglycaemia or the need for admission of the newborn to the Neonatology Unit occurred equally in both groups in line with the results reported by Wilk et al.26

Among the limitations of our work is the fact that it is a retrospective study carried out under exceptional conditions motivated by the pandemic. It was not possible to collect variables, such as physical activity, questionnaires to quantify the level of stress or capillary blood glucose controls, which could also explain part of our results. The strengths of the study include its multicentre design and the fact that the data collected was compared with that of pregnant women from the same time period a year earlier, in order to obtain a control group not subjected to the effects of COVID-19. Last of all, this is a representative study of a Spanish region, given that 11 of the 13 SESCAM hospitals participated and that this included a large number of patients with gestational diabetes for whom data had been recorded, not only referring to follow-up of pregnancy and blood glucose control, but also the pregnancy outcomes. We took this unique opportunity to study the effect of a pandemic on GDM.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, care for GDM in our public health system did not significantly deteriorate during the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this did not prevent a higher number of LGA newborns. It is likely that other variables not collected for our study could have contributed to and also led to a higher level of HbA1c at the end of pregnancy. In future health crises, it would be advisable to give attention to other aspects such as mental health and lifestyle.

Ethical considerationsThe study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Hospital Virgen de la Luz in Cuenca (REG: 2021/PI1021), as the Endocrinology and Nutrition Department of that hospital was the sponsor of the study as part of the Sociedad Castellano Manchega de Endocrinología, Nutrición y Diabetes (SCAMEND) [Castilla-La Mancha Society of Endocrinology, Nutrition and Diabetes]. All researchers adhere to the updated Declaration of Helsinki and the Organic Law on the Protection of Personal Data and Guarantee of Digital Rights. The Ethics Committee approved this retrospective observational study as minimal risk research because it used data collected for routine clinical practice and the requirement for informed consent was waived, while ensuring that the privacy policy was followed.

FundingThis study did not receive any type of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors would also like to thank the following doctors from the listed hospitals for their contribution to the study in terms of data collection:

Hospital Virgen de la Luz: Mubarak Alramadan, David Martín, José Pérez, Carlos Arana and José Luis Quijada.

Hospital Virgen de la Salud: Almudena Vicente, Ana Castro, Rocío Revuelta, Belén Martínez, Ofelia Llamazares, Esther Maqueda and Virginia Peña.

Hospital Universitario de Albacete: Pedro Pinés, Cristina Lamas, Luz López, Lourdes García, Jose Joaquín Alfaro, Antonio José Moya, Marina Jara, Silvia Aznar and Andrés Ruíz de Assin.

Hospital Nuestra Señora del Prado: M.ª Felicidad Durán, Ana Martínez, Mary Llaro, Benito Blanco, Naiara Echepare and Elena Cobos.

Hospital General Universitario de Ciudad Real: Álvaro García-Manzanares, Carlos Roa and Belén Fernández de Bobadilla.

Hospital General de Villarrobledo: M.ª Carmen García.