Quality of life (QoL) in thyroid cancer patients is comparable to patients with other tumours with worse prognosis. The aim was to evaluate QoL in Colombian patients with thyroid carcinoma and to explore the association of QoL scores with patient features.

MethodsThis is a cross-sectional study. The present research was carried out from data obtained for the validation study of the Spanish version of the THYCA-QoL. Adult patients with thyroid carcinoma who underwent total or partial thyroidectomy were included and asked to complete the Spanish-validated versions of the THYCA-QoL and EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaires. The scores of each domain and single items underwent linear transformation to values of 0–100. Comparisons of scale scores with clinical variables were performed.

ResultsWe included 293 patients. The global EORTC QLQ-C30 score was 73.2±22.1 and the domains with poorer values were emotional and cognitive and the symptoms with poorer values were insomnia and fatigue. The global THYCA-QOL score was 28.4±17.8. The domains with poorer values were neuromuscular and psychological and the single items with poorer values were headaches and tingling hands/feet.

ConclusionColombian patients with thyroid cancer have a good prognosis, but they experience important problems related to QoL. QoL was influenced by demographic and clinical factors such as age, sex functional status and clinical stage.

La calidad de vida (CV) en pacientes con cáncer de tiroides es comparable a la de pacientes con otros tumores de peor pronóstico. El objetivo fue evaluar la CV en pacientes latinoamericanos (Colombia) con carcinoma tiroideo y explorar la asociación de los puntajes de CV con las características de los pacientes.

MétodosSe trata de un estudio transversal. La presente investigación se realizó a partir de datos obtenidos para el estudio de validación de la versión española del THYCA-QoL. Se incluyeron pacientes adultos con carcinoma tiroideo sometidos a tiroidectomía total o parcial, a los que se pidió que completaran las versiones validadas en español de los cuestionarios THYCA-QoL y EORTC QLQ-C30. Las puntuaciones de cada dominio y de los ítems individuales se sometieron a una transformación lineal a valores de 0-100. Se realizaron comparaciones de las puntuaciones de las escalas con variables clínicas.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 293 pacientes. La puntuación global del EORTC QLQ-C30 fue de 73,2±22,1 y los dominios con peores valores resultaron ser el emocional y el cognitivo, y los síntomas con peores valores el insomnio y la fatiga. La puntuación global del THYCA-QOL fue de 28,4±17,8 puntos. Los ámbitos con peores valores fueron el neuromuscular y el psicológico, y los ítems individuales con peores valores las cefaleas y el hormigueo en manos/pies.

ConclusionesLos pacientes colombianos con cáncer de tiroides tienen un buen pronóstico, pero experimentan importantes problemas relacionados con la CV. La CV se vio influida por factores demográficos y clínicos como la edad, el sexo, el estado funcional y el estadio clínico.

The incidence of thyroid carcinoma has been increasing worldwide in recent decades.1 The accepted treatment includes thyroidectomy associated with neck dissection, radioactive iodine (RAI) ablation and suppressive therapy with levothyroxine.2 Although thyroid carcinoma has a high overall survival, it has a potential risk of recurrence, which requires long-term follow-up with ultrasound, serum marker analysis and thyroid function tests. Therefore, survivors suffer the effects of treatment and prolonged follow-up, which cause emotional distress and decrease quality of life (QoL).3,4 A substantial percentage of the decline in quality of life is related to factors such as the extent of surgery (total thyroidectomy or lobectomy) or the requirement for excessive TSH suppression, both of which are side effects of treatment rather than illness. Furthermore, the influence of therapeutic complications such as recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis, hypoparathyroidism caused by surgery or sialadenitis, and gonadal dysfunction caused by radioactive iodine ablation is frequently underestimated.

Many studies have demonstrated a decreased QoL in thyroid cancer patients, comparable to patients with other tumours with worse prognosis.5,6 Most of these QoL assessments have been performed with generic instruments, such as EORTC QLQ-C30 and SF-36,7,8 but there are few studies using validated specific instruments.5,9,10 Husson et al11 designed the Health-related Quality of Life Questionnaire for Thyroid Cancer Survivors (THYCA-QoL) in 2013, and it was validated in the Spanish language.12 Although more than 450 million people speak Spanish in South and Central America, there are few studies assessing QoL in Latin American patients with thyroid cancer.13–15

Currently, we use interventions and treatments that are designed and evaluated in different populations that speak other languages but do not know the specific impact on Latin American patients. In addition, Aschebrook-Kilfoy et al9 realized the differences between patients’ and physicians’ concerns, illustrating that thyroid cancer survivors experience several adverse physical and psychological effects that are unrecognized.

The aim of this study was to evaluate QoL in patients with thyroid carcinoma with a generic instrument (EORTC QLQ-C30) and an adapted and validated instrument (THYCA-QoL). Second, our aim was to explore the association of QoL scores with patient features, such as sociodemographic, clinical and treatment characteristics, to identify potential factors that allow health care professionals to provide better supportive care.

Materials and methodsThe present research was carried out from data obtained for the validation study of the Spanish version of the THYCA-QoL.12 This is a descriptive cross-sectional study. The study was approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the Fundacion Colombiana de Cancerologia-Clinica Vida, and written informed consent was obtained.

PopulationAdult patients with histological confirmation of thyroid carcinoma undergoing total or partial thyroidectomy from a single specialized cancer centre who voluntarily agreed to complete the survey were included and asked to complete the Spanish-validated versions of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire and the Spanish version of the THYCA-QoL, which was subsequently validated in the main study.12 This study used a database with information that was previously used to perform the psychometric validation of the ThycaQoL instrument. Patients with reading, hearing or cognitive difficulties, patients with prior history of head and neck tumours and patients who did not consent to participate were excluded. Clinical charts were used to collect demographic information, comorbidity information, ECOG functional scale scores, TNM stage (UICC 7th version), and information regarding the surgical operation, adjuvant radioiodine therapy, T4 supplementation, surgical complications, and vital stages.

InstrumentThe Spanish version of the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire was used after authorization. This is a general tool developed to assess QoL in cancer patients. It has 30 items associated with global quality of life, five functioning scales (physical functioning, role functioning, emotional functioning, cognitive functioning and social functioning), and nine symptom scales (fatigue, nausea and vomiting, pain, dyspnoea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhoea, and financial difficulties). All items are scored on a four-point Likert scale (“not at all,” to “very much”) and are transformed to scores ranging from 0 to 100, where higher values indicate poorer function.

The THYCA-QoL test in Spanish comprises 24 questions divided into seven categories (neuromuscular, voice, concentration, sympathetic, throat/mouth, psychological, and sensory) and seven single items (scar issues, felt chilly, tingling hands/feet, gained weight, headaches, and interest in sex).12 Each question contains four answer categories on a range of 1 to 4 points (with 1 point assigned to the most favourable category and 4 points assigned to the least favourable category) and a time limit (one week for most items, four weeks for sexuality issues).

The questions from the questionnaire were incorporated into a tool that was used to collect personal and clinical data. The medical records were used to get other clinical information about the treatment.

Statistical analysisThe mean and standard deviation of continuous data are provided, while percentages and ranges of categorical variables are shown. A descriptive analysis was performed for each individual item of the THYCA-QoL after categorizing the values into not at all/a little vs. quite a bit/very much and for domain scores. The scores of each domain and single items underwent linear transformation to values of 0–100. For EORTC QLQ-C30 analysis, the Stata qlqc30 command was used. Comparisons of scale scores for categorical variables were performed using the chi-square test, and for continuous variables, we used ANOVA or Student's t test. Even though numerous variables had non-normal distributions, the parametric ANOVA and Student's t tests were used since the sample size was big enough to provide robust results. Finally, a stepwise multivariate linear regression analysis was done using the global value of the EORTC QLQ-C30 and the ThycaQoL as outcomes, adjusted for clinical and demographic characteristics.

We used Stata statistical software (StataCorp, Texas, Version 9.1) and set the significance level to p<.05.

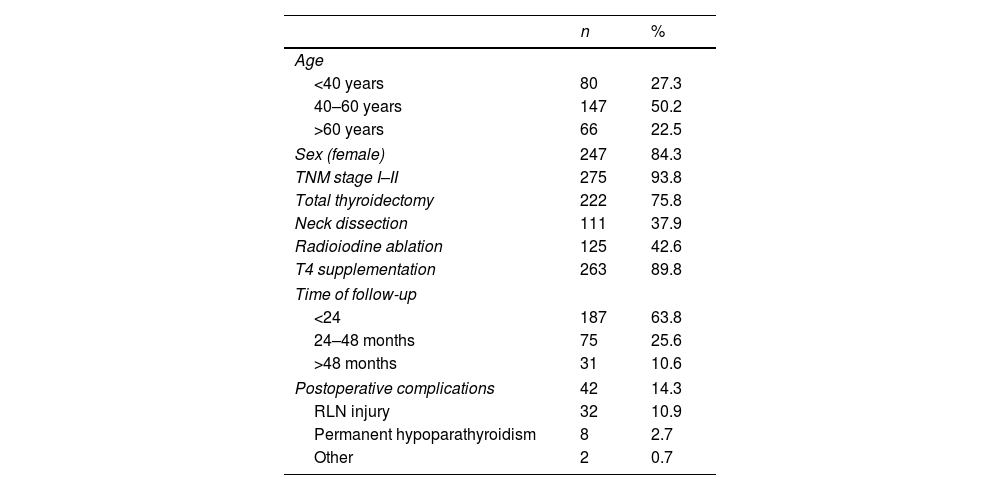

ResultsPopulationA total of 293 patients were recruited between 09/2018 and 03/2019. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical data. The mean age was 47±14.2 years (18–84 years), and 247 (84%) patients were female. Eighteen patients (6.1%) had severe comorbidities, and 49 patients (16.7%) had an ECOG value higher than 0. Almost all patients (96.6%) had papillary histology data. The most frequent type of surgery was total thyroidectomy, and 38% of patients underwent neck dissection. Almost 40% of patients needed RAI ablation. The mean time from diagnosis was 23.6±24.1 months (median 17, range 1–192), and 64% of patients had <24 months of follow-up.

Demographic data of a cohort of thyroid cancer patients.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| <40 years | 80 | 27.3 |

| 40–60 years | 147 | 50.2 |

| >60 years | 66 | 22.5 |

| Sex (female) | 247 | 84.3 |

| TNM stage I–II | 275 | 93.8 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 222 | 75.8 |

| Neck dissection | 111 | 37.9 |

| Radioiodine ablation | 125 | 42.6 |

| T4 supplementation | 263 | 89.8 |

| Time of follow-up | ||

| <24 | 187 | 63.8 |

| 24–48 months | 75 | 25.6 |

| >48 months | 31 | 10.6 |

| Postoperative complications | 42 | 14.3 |

| RLN injury | 32 | 10.9 |

| Permanent hypoparathyroidism | 8 | 2.7 |

| Other | 2 | 0.7 |

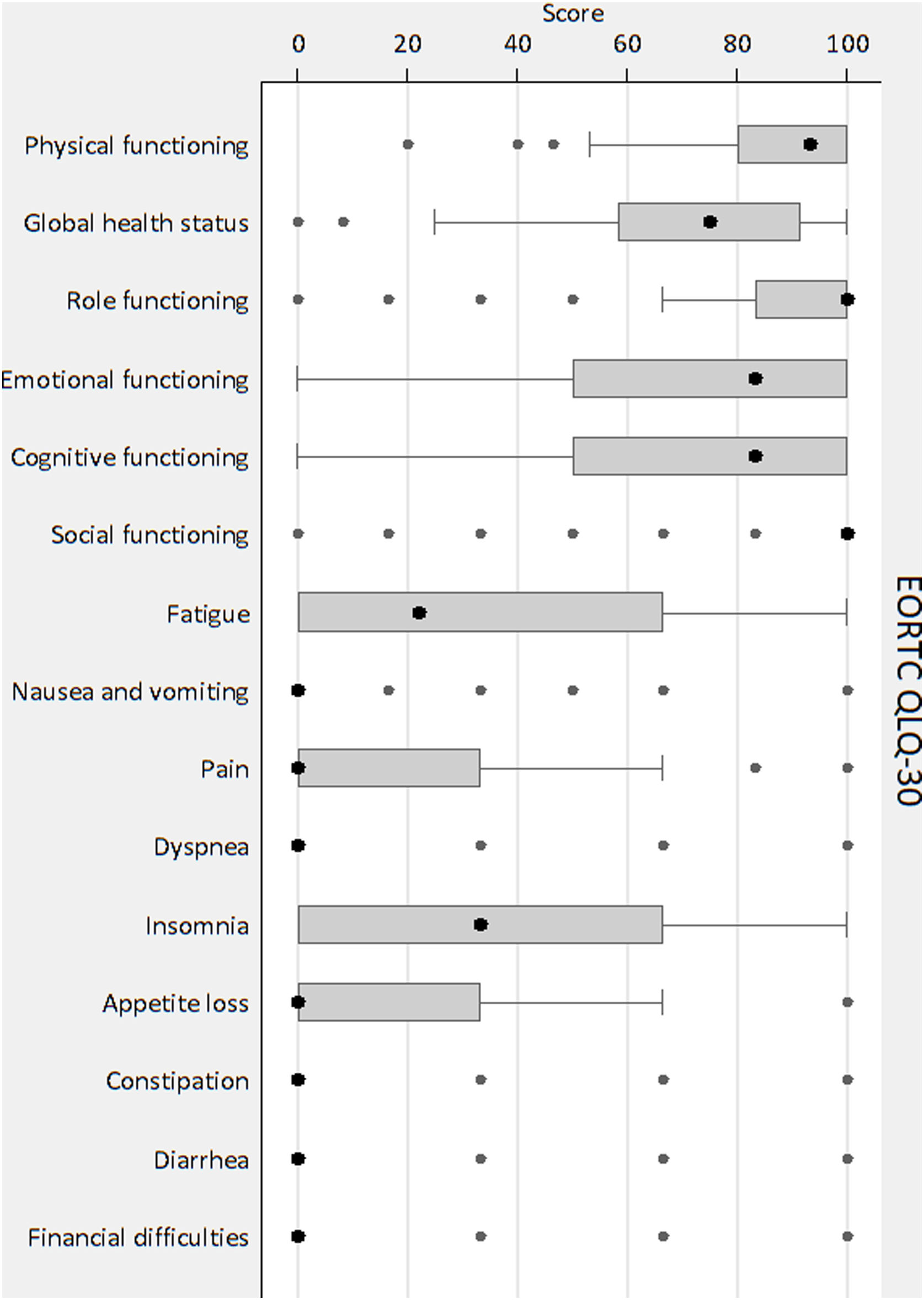

Fig. 1 shows the scores by domains and symptoms. The global EORTC QLQ-C30 score was 73.2±22.1. The domains with poorer values were emotional (69.6±31.6) and cognitive (73.1±28.4), and the symptoms with poorer values were insomnia (36.4±38.9, median 33.3) and fatigue (35.4±32.9, median 22.2).

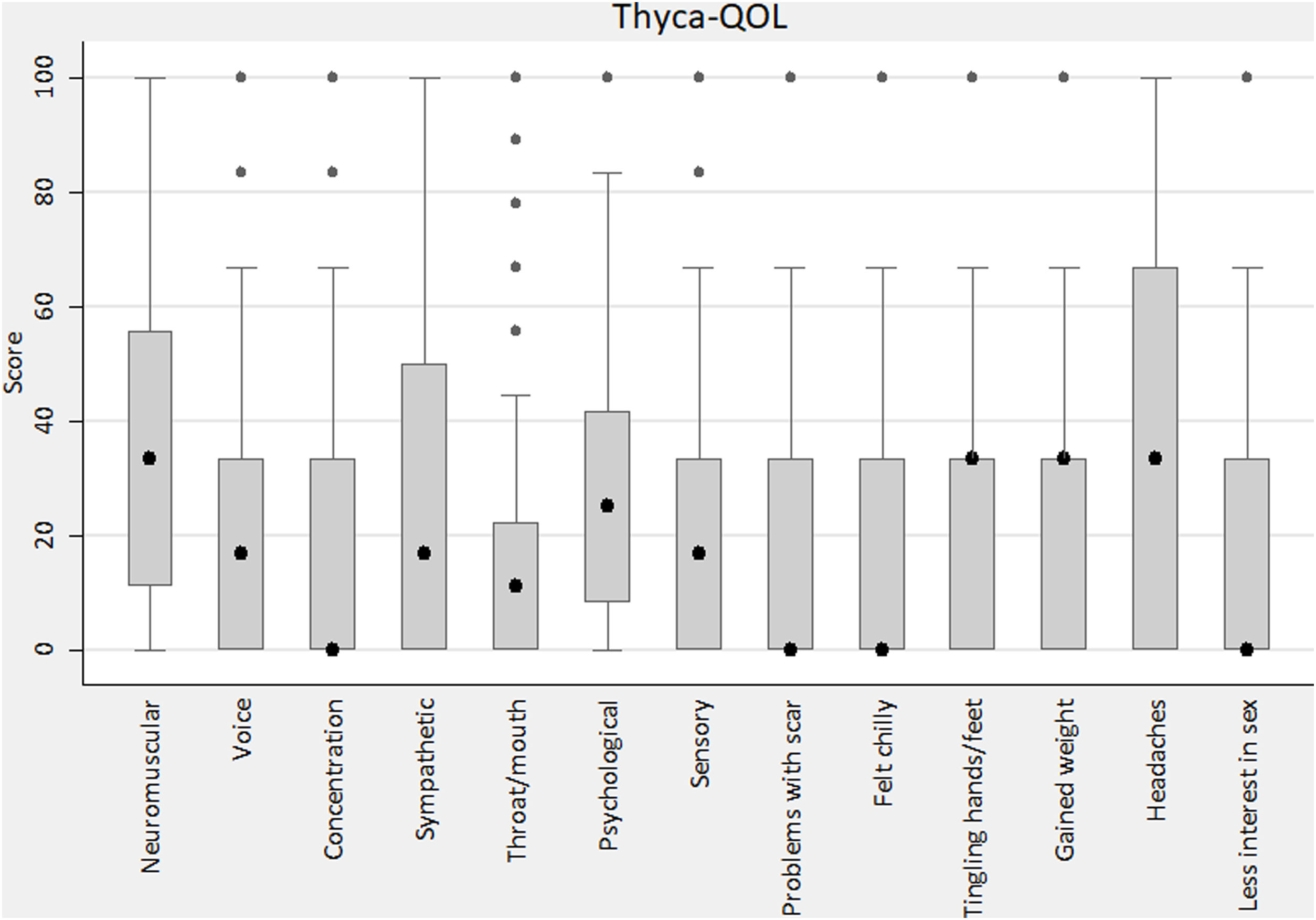

THYCA-QOL descriptionThe items with the less favourable results were abrupt tiredness (quite a bit/very much, 50.9%), muscle/joint pain (40.3%) and headaches (33.4%). The global THYCA-QOL score was 28.4±17.8.

Fig. 2 shows the scores by domains and single items. The domains with poorer values were neuromuscular (34.2±25.9) and psychological (30.8±23.3), and the single items with poorer values were headaches (39.7±36.7) and tingling hands/feet (30.2±33.8).

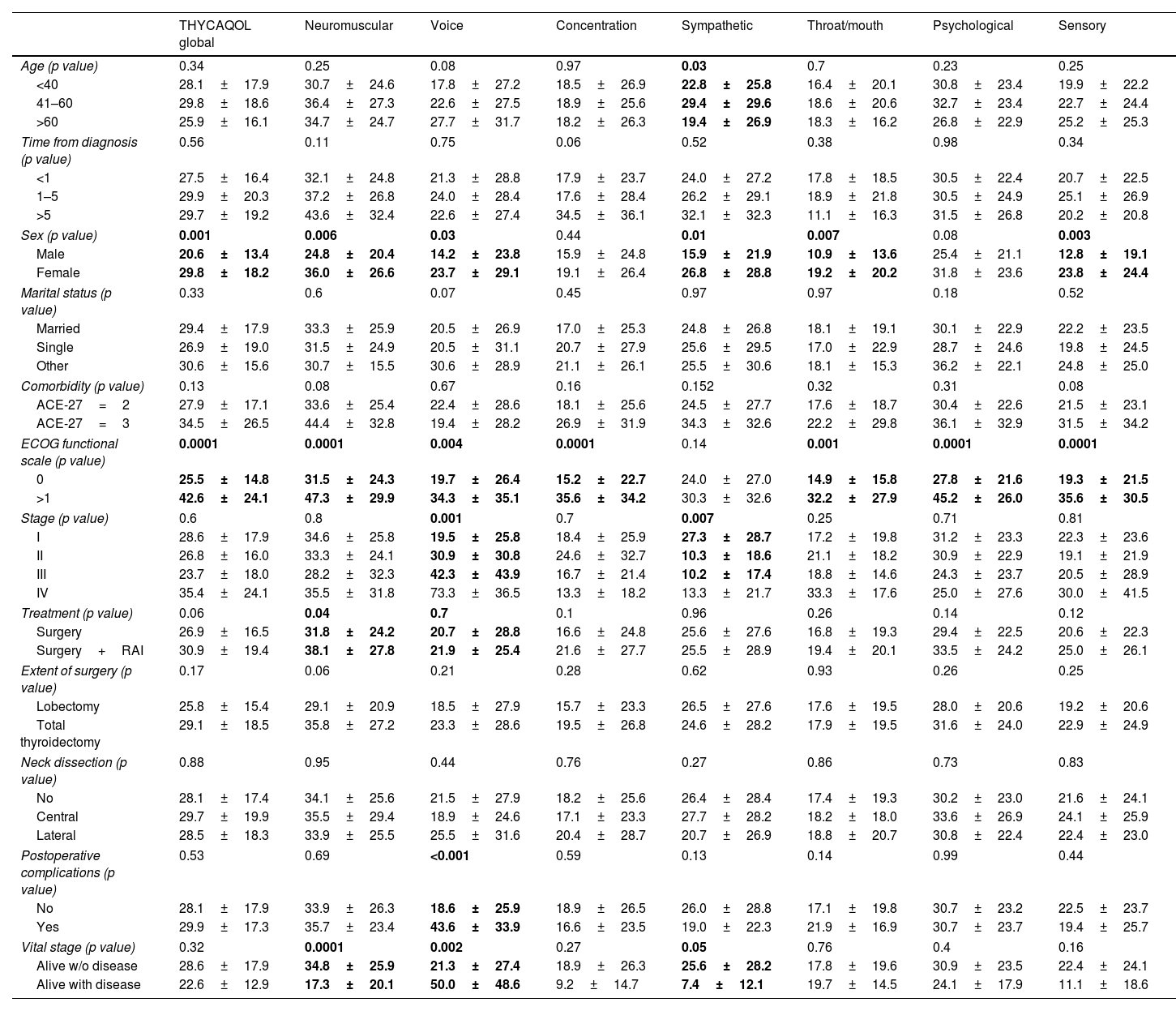

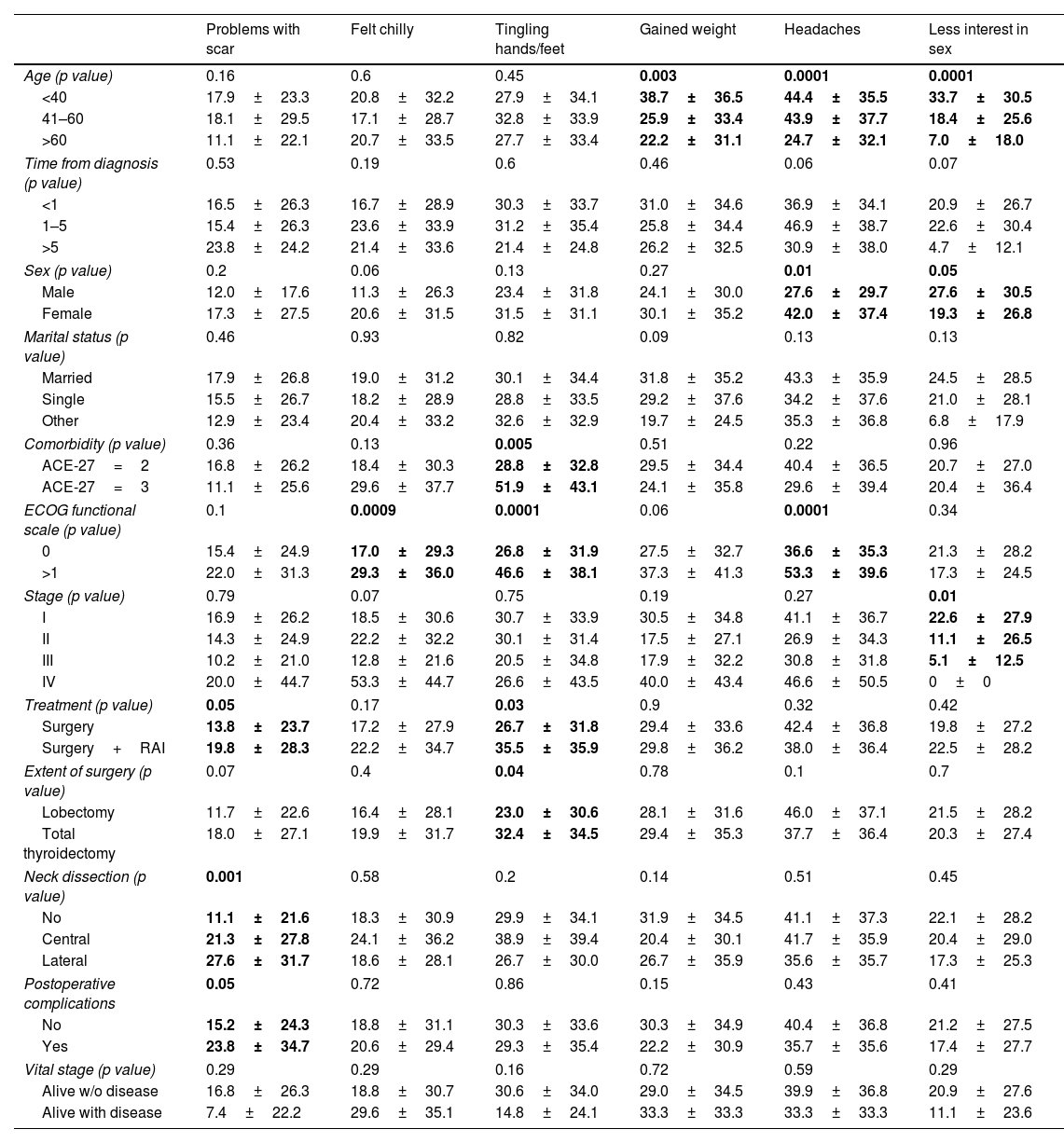

Comparisons of THYCA-QOL scoresTables 2 and 3 show the comparisons of the seven THYCA-QOL domains and the six THYCA-QOL items by demographic and clinical variables, respectively.

Results of the THYCA-QOL scores of seven domains by demographic and clinical characteristics.

| THYCAQOL global | Neuromuscular | Voice | Concentration | Sympathetic | Throat/mouth | Psychological | Sensory | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (p value) | 0.34 | 0.25 | 0.08 | 0.97 | 0.03 | 0.7 | 0.23 | 0.25 |

| <40 | 28.1±17.9 | 30.7±24.6 | 17.8±27.2 | 18.5±26.9 | 22.8±25.8 | 16.4±20.1 | 30.8±23.4 | 19.9±22.2 |

| 41–60 | 29.8±18.6 | 36.4±27.3 | 22.6±27.5 | 18.9±25.6 | 29.4±29.6 | 18.6±20.6 | 32.7±23.4 | 22.7±24.4 |

| >60 | 25.9±16.1 | 34.7±24.7 | 27.7±31.7 | 18.2±26.3 | 19.4±26.9 | 18.3±16.2 | 26.8±22.9 | 25.2±25.3 |

| Time from diagnosis (p value) | 0.56 | 0.11 | 0.75 | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 0.98 | 0.34 |

| <1 | 27.5±16.4 | 32.1±24.8 | 21.3±28.8 | 17.9±23.7 | 24.0±27.2 | 17.8±18.5 | 30.5±22.4 | 20.7±22.5 |

| 1–5 | 29.9±20.3 | 37.2±26.8 | 24.0±28.4 | 17.6±28.4 | 26.2±29.1 | 18.9±21.8 | 30.5±24.9 | 25.1±26.9 |

| >5 | 29.7±19.2 | 43.6±32.4 | 22.6±27.4 | 34.5±36.1 | 32.1±32.3 | 11.1±16.3 | 31.5±26.8 | 20.2±20.8 |

| Sex (p value) | 0.001 | 0.006 | 0.03 | 0.44 | 0.01 | 0.007 | 0.08 | 0.003 |

| Male | 20.6±13.4 | 24.8±20.4 | 14.2±23.8 | 15.9±24.8 | 15.9±21.9 | 10.9±13.6 | 25.4±21.1 | 12.8±19.1 |

| Female | 29.8±18.2 | 36.0±26.6 | 23.7±29.1 | 19.1±26.4 | 26.8±28.8 | 19.2±20.2 | 31.8±23.6 | 23.8±24.4 |

| Marital status (p value) | 0.33 | 0.6 | 0.07 | 0.45 | 0.97 | 0.97 | 0.18 | 0.52 |

| Married | 29.4±17.9 | 33.3±25.9 | 20.5±26.9 | 17.0±25.3 | 24.8±26.8 | 18.1±19.1 | 30.1±22.9 | 22.2±23.5 |

| Single | 26.9±19.0 | 31.5±24.9 | 20.5±31.1 | 20.7±27.9 | 25.6±29.5 | 17.0±22.9 | 28.7±24.6 | 19.8±24.5 |

| Other | 30.6±15.6 | 30.7±15.5 | 30.6±28.9 | 21.1±26.1 | 25.5±30.6 | 18.1±15.3 | 36.2±22.1 | 24.8±25.0 |

| Comorbidity (p value) | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.67 | 0.16 | 0.152 | 0.32 | 0.31 | 0.08 |

| ACE-27=2 | 27.9±17.1 | 33.6±25.4 | 22.4±28.6 | 18.1±25.6 | 24.5±27.7 | 17.6±18.7 | 30.4±22.6 | 21.5±23.1 |

| ACE-27=3 | 34.5±26.5 | 44.4±32.8 | 19.4±28.2 | 26.9±31.9 | 34.3±32.6 | 22.2±29.8 | 36.1±32.9 | 31.5±34.2 |

| ECOG functional scale (p value) | 0.0001 | 0.0001 | 0.004 | 0.0001 | 0.14 | 0.001 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| 0 | 25.5±14.8 | 31.5±24.3 | 19.7±26.4 | 15.2±22.7 | 24.0±27.0 | 14.9±15.8 | 27.8±21.6 | 19.3±21.5 |

| >1 | 42.6±24.1 | 47.3±29.9 | 34.3±35.1 | 35.6±34.2 | 30.3±32.6 | 32.2±27.9 | 45.2±26.0 | 35.6±30.5 |

| Stage (p value) | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.001 | 0.7 | 0.007 | 0.25 | 0.71 | 0.81 |

| I | 28.6±17.9 | 34.6±25.8 | 19.5±25.8 | 18.4±25.9 | 27.3±28.7 | 17.2±19.8 | 31.2±23.3 | 22.3±23.6 |

| II | 26.8±16.0 | 33.3±24.1 | 30.9±30.8 | 24.6±32.7 | 10.3±18.6 | 21.1±18.2 | 30.9±22.9 | 19.1±21.9 |

| III | 23.7±18.0 | 28.2±32.3 | 42.3±43.9 | 16.7±21.4 | 10.2±17.4 | 18.8±14.6 | 24.3±23.7 | 20.5±28.9 |

| IV | 35.4±24.1 | 35.5±31.8 | 73.3±36.5 | 13.3±18.2 | 13.3±21.7 | 33.3±17.6 | 25.0±27.6 | 30.0±41.5 |

| Treatment (p value) | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.7 | 0.1 | 0.96 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.12 |

| Surgery | 26.9±16.5 | 31.8±24.2 | 20.7±28.8 | 16.6±24.8 | 25.6±27.6 | 16.8±19.3 | 29.4±22.5 | 20.6±22.3 |

| Surgery+RAI | 30.9±19.4 | 38.1±27.8 | 21.9±25.4 | 21.6±27.7 | 25.5±28.9 | 19.4±20.1 | 33.5±24.2 | 25.0±26.1 |

| Extent of surgery (p value) | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.62 | 0.93 | 0.26 | 0.25 |

| Lobectomy | 25.8±15.4 | 29.1±20.9 | 18.5±27.9 | 15.7±23.3 | 26.5±27.6 | 17.6±19.5 | 28.0±20.6 | 19.2±20.6 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 29.1±18.5 | 35.8±27.2 | 23.3±28.6 | 19.5±26.8 | 24.6±28.2 | 17.9±19.5 | 31.6±24.0 | 22.9±24.9 |

| Neck dissection (p value) | 0.88 | 0.95 | 0.44 | 0.76 | 0.27 | 0.86 | 0.73 | 0.83 |

| No | 28.1±17.4 | 34.1±25.6 | 21.5±27.9 | 18.2±25.6 | 26.4±28.4 | 17.4±19.3 | 30.2±23.0 | 21.6±24.1 |

| Central | 29.7±19.9 | 35.5±29.4 | 18.9±24.6 | 17.1±23.3 | 27.7±28.2 | 18.2±18.0 | 33.6±26.9 | 24.1±25.9 |

| Lateral | 28.5±18.3 | 33.9±25.5 | 25.5±31.6 | 20.4±28.7 | 20.7±26.9 | 18.8±20.7 | 30.8±22.4 | 22.4±23.0 |

| Postoperative complications (p value) | 0.53 | 0.69 | <0.001 | 0.59 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.99 | 0.44 |

| No | 28.1±17.9 | 33.9±26.3 | 18.6±25.9 | 18.9±26.5 | 26.0±28.8 | 17.1±19.8 | 30.7±23.2 | 22.5±23.7 |

| Yes | 29.9±17.3 | 35.7±23.4 | 43.6±33.9 | 16.6±23.5 | 19.0±22.3 | 21.9±16.9 | 30.7±23.7 | 19.4±25.7 |

| Vital stage (p value) | 0.32 | 0.0001 | 0.002 | 0.27 | 0.05 | 0.76 | 0.4 | 0.16 |

| Alive w/o disease | 28.6±17.9 | 34.8±25.9 | 21.3±27.4 | 18.9±26.3 | 25.6±28.2 | 17.8±19.6 | 30.9±23.5 | 22.4±24.1 |

| Alive with disease | 22.6±12.9 | 17.3±20.1 | 50.0±48.6 | 9.2±14.7 | 7.4±12.1 | 19.7±14.5 | 24.1±17.9 | 11.1±18.6 |

The comparisons with bold values showed statistically significant differences.

Results of the THYCA-QOL scores of six symptoms by demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Problems with scar | Felt chilly | Tingling hands/feet | Gained weight | Headaches | Less interest in sex | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (p value) | 0.16 | 0.6 | 0.45 | 0.003 | 0.0001 | 0.0001 |

| <40 | 17.9±23.3 | 20.8±32.2 | 27.9±34.1 | 38.7±36.5 | 44.4±35.5 | 33.7±30.5 |

| 41–60 | 18.1±29.5 | 17.1±28.7 | 32.8±33.9 | 25.9±33.4 | 43.9±37.7 | 18.4±25.6 |

| >60 | 11.1±22.1 | 20.7±33.5 | 27.7±33.4 | 22.2±31.1 | 24.7±32.1 | 7.0±18.0 |

| Time from diagnosis (p value) | 0.53 | 0.19 | 0.6 | 0.46 | 0.06 | 0.07 |

| <1 | 16.5±26.3 | 16.7±28.9 | 30.3±33.7 | 31.0±34.6 | 36.9±34.1 | 20.9±26.7 |

| 1–5 | 15.4±26.3 | 23.6±33.9 | 31.2±35.4 | 25.8±34.4 | 46.9±38.7 | 22.6±30.4 |

| >5 | 23.8±24.2 | 21.4±33.6 | 21.4±24.8 | 26.2±32.5 | 30.9±38.0 | 4.7±12.1 |

| Sex (p value) | 0.2 | 0.06 | 0.13 | 0.27 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Male | 12.0±17.6 | 11.3±26.3 | 23.4±31.8 | 24.1±30.0 | 27.6±29.7 | 27.6±30.5 |

| Female | 17.3±27.5 | 20.6±31.5 | 31.5±31.1 | 30.1±35.2 | 42.0±37.4 | 19.3±26.8 |

| Marital status (p value) | 0.46 | 0.93 | 0.82 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Married | 17.9±26.8 | 19.0±31.2 | 30.1±34.4 | 31.8±35.2 | 43.3±35.9 | 24.5±28.5 |

| Single | 15.5±26.7 | 18.2±28.9 | 28.8±33.5 | 29.2±37.6 | 34.2±37.6 | 21.0±28.1 |

| Other | 12.9±23.4 | 20.4±33.2 | 32.6±32.9 | 19.7±24.5 | 35.3±36.8 | 6.8±17.9 |

| Comorbidity (p value) | 0.36 | 0.13 | 0.005 | 0.51 | 0.22 | 0.96 |

| ACE-27=2 | 16.8±26.2 | 18.4±30.3 | 28.8±32.8 | 29.5±34.4 | 40.4±36.5 | 20.7±27.0 |

| ACE-27=3 | 11.1±25.6 | 29.6±37.7 | 51.9±43.1 | 24.1±35.8 | 29.6±39.4 | 20.4±36.4 |

| ECOG functional scale (p value) | 0.1 | 0.0009 | 0.0001 | 0.06 | 0.0001 | 0.34 |

| 0 | 15.4±24.9 | 17.0±29.3 | 26.8±31.9 | 27.5±32.7 | 36.6±35.3 | 21.3±28.2 |

| >1 | 22.0±31.3 | 29.3±36.0 | 46.6±38.1 | 37.3±41.3 | 53.3±39.6 | 17.3±24.5 |

| Stage (p value) | 0.79 | 0.07 | 0.75 | 0.19 | 0.27 | 0.01 |

| I | 16.9±26.2 | 18.5±30.6 | 30.7±33.9 | 30.5±34.8 | 41.1±36.7 | 22.6±27.9 |

| II | 14.3±24.9 | 22.2±32.2 | 30.1±31.4 | 17.5±27.1 | 26.9±34.3 | 11.1±26.5 |

| III | 10.2±21.0 | 12.8±21.6 | 20.5±34.8 | 17.9±32.2 | 30.8±31.8 | 5.1±12.5 |

| IV | 20.0±44.7 | 53.3±44.7 | 26.6±43.5 | 40.0±43.4 | 46.6±50.5 | 0±0 |

| Treatment (p value) | 0.05 | 0.17 | 0.03 | 0.9 | 0.32 | 0.42 |

| Surgery | 13.8±23.7 | 17.2±27.9 | 26.7±31.8 | 29.4±33.6 | 42.4±36.8 | 19.8±27.2 |

| Surgery+RAI | 19.8±28.3 | 22.2±34.7 | 35.5±35.9 | 29.8±36.2 | 38.0±36.4 | 22.5±28.2 |

| Extent of surgery (p value) | 0.07 | 0.4 | 0.04 | 0.78 | 0.1 | 0.7 |

| Lobectomy | 11.7±22.6 | 16.4±28.1 | 23.0±30.6 | 28.1±31.6 | 46.0±37.1 | 21.5±28.2 |

| Total thyroidectomy | 18.0±27.1 | 19.9±31.7 | 32.4±34.5 | 29.4±35.3 | 37.7±36.4 | 20.3±27.4 |

| Neck dissection (p value) | 0.001 | 0.58 | 0.2 | 0.14 | 0.51 | 0.45 |

| No | 11.1±21.6 | 18.3±30.9 | 29.9±34.1 | 31.9±34.5 | 41.1±37.3 | 22.1±28.2 |

| Central | 21.3±27.8 | 24.1±36.2 | 38.9±39.4 | 20.4±30.1 | 41.7±35.9 | 20.4±29.0 |

| Lateral | 27.6±31.7 | 18.6±28.1 | 26.7±30.0 | 26.7±35.9 | 35.6±35.7 | 17.3±25.3 |

| Postoperative complications | 0.05 | 0.72 | 0.86 | 0.15 | 0.43 | 0.41 |

| No | 15.2±24.3 | 18.8±31.1 | 30.3±33.6 | 30.3±34.9 | 40.4±36.8 | 21.2±27.5 |

| Yes | 23.8±34.7 | 20.6±29.4 | 29.3±35.4 | 22.2±30.9 | 35.7±35.6 | 17.4±27.7 |

| Vital stage (p value) | 0.29 | 0.29 | 0.16 | 0.72 | 0.59 | 0.29 |

| Alive w/o disease | 16.8±26.3 | 18.8±30.7 | 30.6±34.0 | 29.0±34.5 | 39.9±36.8 | 20.9±27.6 |

| Alive with disease | 7.4±22.2 | 29.6±35.1 | 14.8±24.1 | 33.3±33.3 | 33.3±33.3 | 11.1±23.6 |

The comparisons with bold values showed statistically significant differences.

There were significant differences in most domains for sex (higher scores for female patients) and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) functional scale (higher scores for patients with ECOG>1). The sympathetic domain score was higher in young people, women, early clinical stage patients and patients surviving without disease. The neuromuscular domain score was higher in women, patients with ECOG>1, patients with who underwent surgical treatment and patients surviving without disease. The voice domain score was higher for women, patients with ECOG>1, patients with advanced clinical stage, with complications and patients surviving with disease.

Regarding individual items, tingling in hands/feet has higher scores in patients with higher comorbidities, patients with ECOG>1, patients who underwent surgery treatment and who underwent total thyroidectomy. The headache item had higher scores in young patients and women, and ECOG>1 and less interest in sex had higher scores in young patients, males and patients with early clinical stages.

The EORTC QLQ-C30 linear regression analysis showed that ECOG functional status was the only variable with a statistically significant association (B coefficient=−21.2, p=0.001). Female sex (B coefficient=9.6, p=0.002), functional status by ECOG (B coefficient=16.7, p=0.001), and use of RAI ablation (B coefficient=4.1, p=0.03) all showed a statistically significant association in the Thyca QoL scale evaluation.

DiscussionThe measurement of quality of life (QoL) is an essential tool for determining the impact of illness and therapy. Because the death and recurrence rates for thyroid cancer are low, people live with the diagnosis for a longer period. Recent evidence reveals that QoL in thyroid cancer patients may be as poor as in other forms of malignancies with a less favourable outcome.6

Unfortunately, no specific instruments have been validated in Spanish yet, and the few research that exist employ general instruments. Novoa et al.,13 used the SF-36 instrument to assess QoL in 75 patients with thyroid cancer in Colombia and found low scores in the physical, social, and mental domains, while Vega-Vasquez et al.14 used the UW-QOL instrument to assess QoL in 75 patients in Puerto Rico and found low scores in the physical and social subscales. Husson et al.,11 developed the THYCA-QoL questionnaire in 2013 as a specialized tool to evaluate QoL in patients with thyroid cancer, and it was the first to adhere to established methodological principles.7,10,16–20 However, there is no information about specific QoL in Latin American patients with thyroid cancer.

The results of this study support the findings that the QoL of patients with thyroid carcinoma decreases, even after being free of disease.3,5 In general, emotional function and cognitive function were the most adversely affected domains in the EORTC QLQ-C30, and patients had moderate problems with fatigue and sleep. It has been described that almost 34% of patients with thyroid cancer suffer distress even years after diagnosis, and this is triggered by emotional problems.21 The results of the EORTC QLQ-C30 global scores of our patients with thyroid cancer were higher than those reported in Korea and Austria3,22 but similar to those reported in the Netherlands, UK and China.4,7,23 The only available study reporting QoL measured with the EORTC QLQ-C30 questionnaire in a Latin American population was reported by Ramim et al.,24 in Brazil. The global score was similar to our study, but differences were found in social functioning (77.9 vs. 91.8), fatigue (24 vs. 35), insomnia (26 vs. 36), constipation (26 vs. 9) and financial difficulties (29 vs. 10). These comparisons show that although the global QoL measured by a generic instrument is similar, the burden of each domain and symptom is different between populations.

Our study is the first clinical application of the validated THYCA-QOL instrument to the Spanish language in Colombian patients. In comparison with generic instruments, the use of the specific THYCA-QOL questionnaire offers other perspectives to understand the QoL of thyroid cancer patients. Our patients scores were different from those in the original study by Husson et al.,5 with higher scores in the psychological domain and lower scores in the symptoms of felt chilly, tingling, gained weight and headaches. Ahn et al.,20 who included patients with microcarcinoma treated with total thyroidectomy and radioiodine ablation, showed worse scores than those reported here, while Lan et al.,25 who included patients treated with radiofrequency ablation, showed better scores, which suggests that tumour stage and treatment play an important role in the evaluation of QoL.

The analysis of the THYCA-QoL domain and item scores by clinical variables demonstrated specific association with sex and functional status. In comparison with men, women had significantly higher scores in all domains except in concentration and psychological domains, and these women exhibited higher chilliness and headache scores but lower interest in sex scores. Pak et al.,26 found that women reported more uncomfortable symptoms related to RAI ablation treatment, but specific studies centred on gender differences in QoL were not found. These differences by sex have been explained by disparities in coping strategies and illness perception between men and women.27 Regarding ECOG functional status, women had higher scores in all domains except in the sympathetic domains. Age was related to the sympathetic domain, weight gain, headaches, and less interest in sex, with lower scores in patients >60years old, similar to other results reported.7,10,28 This can be explained by overlapping symptoms related to menopause in patients <60 years, negative emotions related to body image in younger patients and changing perception of the disease in older patients.10,28

Patients with higher clinical stages reported higher scores in the voice domain, which is related to the extension of treatment. Use of RAI was associated with higher scores only in the neuromuscular domain and scar and tingling items. Lee et al.,3 and Ahn et al.20 did not find any effect on QoL when evaluating the use of RAI. We could not identify a difference in domains or items regarding the extension of neck dissection, except for the scar symptom, which is a consequence of the length of the scar. These findings are contradictory to those of studies that suggest that extent of surgery is a relevant factor related to QoL.15,24

In addition, we could not find an association between the time of diagnosis and QoL scores. Husson et al.,5 found associations of time of diagnosis with the voice, concentration, sympathetic, throat/mouth and psychological domains and with the scar and interest in sex items in the Netherlands. This relationship with time has been explained by the length of time needed for the adjustment of levothyroxine support and by the effect of temporary complications, such as hypoparathyroidism and subclinical hyperthyroidism, induced by TSH suppression.22

In the multivariate analysis, only ECOG was related to the global quality of life score measured with the EORTC QLQ-C30, whereas other factors such as sex and use of RAI ablation were associated when the THYCA-QoL scale was employed, supporting the notion that generic instruments have limitations when measuring quality of life in patients with thyroid cancer.

Some limitations of this work are related to the cross-sectional design, sample size and the possibility of selection bias due to the recruitment of patients in a reference centre, which does not represent the general population. As QoL is a continuum that can change with different factors, the cross-sectional design impedes the evaluation of these changes. In addition, most patients had a follow-up of less than 24 months, and it has been suggested that patients with longer follow-up times could improve their QoL. Besides, some of our patients did not receive levothyroxine support during their preparation for RAI ablation, and this factor can affect the evaluation of QoL.

ConclusionIn conclusion, this study shows that thyroid cancer patients experience important problems related to QoL. Relevant differences were found in comparisons with QoL assessments in other populations. QoL was influenced by demographic and clinical factors such as sex, functional status, treatment, and clinical stage. Screening and awareness of these factors during clinical assessment could improve outcomes. A prospective longitudinal assessment of individual QoL scores is necessary to understand temporal variations.

Availability of data and materialThe data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Author contributionAll the authors contributed to the study's conception and design. The material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Oscar Gomez and Alvaro Sanabria. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Ethics approvalThis study was approved by the Ethics in Research Committee of the Fundacion Colombiana de Cancerologia-Clinica Vida.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sector.

Conflict of interestThe authors have stated explicitly that there are no conflicts of interest in connection with this article.