With the increasing prevalence of obesity among women of reproductive age, the detrimental effects on maternal and neonatal health are increasing. The objective of this review is to summarise the evidence that comprehensive management of weight control in women of reproductive age has on maternal-fetal outcomes. First, the impact that obesity has on fertility and pregnancy is described and then the specific aspects of continued weight management in each of the stages (preconception, pregnancy and postpartum) during these years are outlined, not only to benefit women affected by obesity before pregnancy, but also to avoid and reverse weight gain during pregnancy that complicates future pregnancies.

Finally, the special planning and follow-up needs of women with a history of bariatric surgery are discussed in order to avoid nutritional deficiencies and/or surgical complications that endanger the mother or affect fetal development.

Con el incremento de la prevalencia de la obesidad entre las mujeres en edad reproductiva están aumentando los efectos perjudiciales para la salud materna y neonatal. El objetivo de esta revisión es resumir la evidencia que el manejo integral del control ponderal de las mujeres en edad reproductiva tiene sobre los resultados materno-fetales. Primeramente, se describe el impacto que la obesidad tiene en la fertilidad y la gestación y a continuación se destacan los aspectos específicos del manejo continuado del peso en cada una de las etapas (preconcepción, embarazo y postparto) durante estos años, no sólo en las mujeres afectas de obesidad antes de la gestación, sino también para evitar y revertir la ganancia de peso durante el embarazo que complique las gestaciones futuras.

Finalmente, se discuten las necesidades especiales de planificación y seguimiento de las mujeres con antecedente de cirugía bariátrica para evitar deficiencias nutricionales y/o complicaciones quirúrgicas que pongan en peligro a la madre o puedan afectar el desarrollo fetal.

Obesity in pregnancy is a currently a major challenge in obstetric care due to its prevalence, the adverse impact on both mother and foetus and the consequences for the health of present and future generations. This review describes the influence of obesity on reproductive health before and during pregnancy and postpartum. It also discusses the multidisciplinary management of obesity during a woman's reproductive period based on the Spanish- and English-language scientific literature on the subject published from 2010 to 2022.

In Spain, the prevalence of overweight and obesity in women of childbearing age (18–44) is 11.1%,1 with a similar rate of obesity reported in women during pregnancy.2 Obesity in this age group is not only important because of its prevalence, but also because it has a negative impact on the different reproductive stages: menstrual cycle and ovulation, achieving pregnancy spontaneously and through assisted reproductive techniques (ART) and in terms of maternal/foetal complications during the pregnancy.

Impact of obesity on fertilityThe majority of men and women with obesity are fertile, although obesity increases the risk of infertility. A number of elements could explain the negative impact obesity has on fertility: ovulatory dysfunction, altered oocyte quality, endometrial dysfunction and affected male fertility. This section summarises the available evidence on the effects of obesity on female fertility.

Alteration of the menstrual cycle and ovulatory dysfunctionMost studies concur that 30%–36% of women with obesity experience menstrual cycle irregularity, and the prevalence of oligomenorrhoea and amenorrhoea increases with the degree of obesity.3 Ovulatory dysfunction is also more common in women with obesity, and anovulatory infertility is more prevalent as body mass index (BMI) increases. Women with obesity and anovulation have greater abdominal obesity than patients with normal ovulation with a similar BMI, so abdominal obesity would therefore be a better predictor of ovulatory dysfunction.3 However, it is important to note that polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) is a confounding factor in determining the effects of obesity on ovulation, and this will be briefly discussed in a specific section.

Obese patients with regular cycles and no ovulatory disorders also experience subclinical endocrine changes which, when exacerbated, induce menstrual and ovulatory abnormalities. Compared to women of normal weight, the ovulatory cycles of women with obesity have lower total concentrations throughout the cycle of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinising hormone (LH) and lower concentrations of progesterone in the luteal phase, reduced LH pulse amplitude in the early follicular phase, lengthening of the follicular phase and shortening of the luteal phase.4 Insulin resistance associated with abdominal obesity increases ovarian androgen production and reduces the liver's production of sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG). Increased peripheral aromatisation of androgen to oestrogen in adipose tissue, together with altered levels of adipokines such as leptin and IGF-BP, contribute to hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis disruption and menstrual disturbances.3

Altered oocyte qualityObtaining oocytes surrounded by cumulus cells and follicular fluid in in vitro fertilisation (IVF) is a model for studying the intrafollicular endocrinological and metabolic environment. In this context, the patient with obesity has higher intrafollicular concentration of insulin, inflammatory markers and free fatty acids, and these alterations are correlated with abnormalities in the cumulus-oocyte complex.3,4 The results on the fertilisation capacity of oocytes from women who are overweight or obese are inconsistent, but obesity influences the development of the resulting embryos, although the proportion of euploid embryos is not reduced when BMI increases.3

Animal model studies have shown that lipotoxicity affects oocyte quality and development through the intracellular accumulation of lipids, oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction, producing meiotic defects and alterations in fertilisation and development from the pre-implantation embryo through to the newborn.5 Oocytes from women with BMI > 35 kg/m2 have a higher prevalence of meiotic spindle and chromosome alignment abnormalities compared to patients with normal BMI.6

Endometrial dysfunctionObesity is a risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. From the standpoint of fertility, endometrial immunohistochemistry studies found a correlation between increased BMI and a significant reduction in the glandular expression of oestrogen and progesterone receptors.7 At molecular level, women with obesity present differences in the gene expression pattern in the implantation window, the period when the endometrium is receptive for embryo implantation, and these differences are more pronounced in women with infertility or PCOS.8

The reproductive outcomes of oocyte recipients with obesity whose embryos came from oocyte donors of normal weight have made it possible to study the impact of obesity on the receptiveness of the endometrium, although the results from different studies are discordant.3 However, a combined analysis of the available evidence suggests a potential negative impact of obesity on both the oocyte and the endometrium.4

Impact of obesity on assisted reproduction techniquesApart from the effects of obesity on the quality of the oocyte, endometrium and sperm, obesity is associated with poorer outcomes in fertility treatments and in ART. First of all, women with obesity have a lower response to ovarian stimulation. In ovulation induction treatments, there is less likelihood of ovulation using clomifene citrate, they require higher doses of gonadotropins and a smaller number of follicles develop.3 In IVF cycles, ovarian stimulation takes longer and requires a higher dose of gonadotropins, fewer oocytes are obtained and there is an increased rate of cancelled cycles due to suboptimal or no response to stimulation.3 A reduction in the expression of the FSH receptor in the granulosa cells of the ovarian follicle and a decrease in the production of oestradiol have been found, which could be mediated by the hyperinsulinaemia associated with obesity.9

According to the results of a recent meta-analysis, women with obesity have a lower likelihood of live birth in IVF compared to women with normal BMI (RR [95% CI] 0.85 [0.82−0.87]), and the prognosis is worse when obesity is associated with PCOS.10 However, a woman's age has a huge influence on fertility and ART outcomes, so as a woman's age increases, BMI has less of an impact on the live birth rate from IVF.3 Lastly, the majority of the studies focused on the impact of BMI in women, but male obesity could also have a negative effect on the development of the pre-implantation embryo, and the results regarding its impact on IVF pregnancy, abortion and live birth rates are contradictory, the results of a meta-analysis point to a reduction in the IVF live birth rate in obese men.11

Before an IVF cycle, a couple with obesity should be assessed and advised by a multidisciplinary team, considering BMI, abdominal obesity and comorbidities, not only to establish the potential negative consequences for fertility and maternal foetal health, but also to determine the safety of the technique in the woman, particularly the follicular puncture-aspiration to obtain oocytes under sedation required by IVF techniques.

Obesity, polycystic ovary syndrome and reproductionPCOS is the most common cause of infertility due to anovulation. Women with PCOS have a higher likelihood of obesity (prevalence ranging from 14% to 75% depending on the population studied), longitudinal weight gain and abdominal obesity compared to women without PCOS.12 Obesity and PCOS are two conditions with complex pathophysiologies and it is not clear which one of them acts as a cause or as a consequence of the other. Obesity exacerbates different reproductive and metabolic aspects of PCOS, which contributes to increasing the likelihood of menstrual irregularity and oligo/anovulation, with a negative impact on these patients' fertility. Once pregnant, women with PCOS have an increased risk of gestational hypertension, preeclampsia, gestational diabetes (GD) and preterm birth.13 Obesity and PCOS are independent risk factors for several of these gestational complications, and when they present simultaneously their negative effects on pregnancy can be amplified.13 Weight loss is the first therapeutic step in patients with PCOS and obesity and is known to improve reproductive, metabolic and psychological parameters.14 Weight loss interventions that achieve a reduction of at least 5%–10% can reverse the negative effects on ovulation and fertility in these women.15 However, a systematic review of the literature found a high degree of heterogeneity among the interventions studied and a high drop-out rate, so it is not clear whether one strategy is better than the rest or for how long it should be maintained, or whether, if anovulation is not resolved after a weight loss of 5%–10%, proceeding with the intervention is indicated.16

Maternal-foetal complications in pregnancy in obese womenObesity is associated with different short-term and long-term adverse consequences. Overweight or obese woman have an increased risk of spontaneous abortion and euploid abortion compared to patients with normal weight.3 The pregnancies of women with obesity are at increased risk of a different complications, including GD, hypertensive disease of pregnancy (gestational hypertension or preeclampsia), foetal malformations, prematurity, both spontaneous and induced by other complications, Caesarean delivery, postpartum haemorrhage and thromboembolism.4,17 However, maternal obesity does not only have a negative impact on the health of women, but also on their children's. Different observational studies indicate a close relationship between maternal weight and obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors in their offspring.4 Pre-gestational BMI is highly correlated with adiposity not only in the newborn, but also in childhood, adolescence and adulthood, potentially affecting health throughout life.4

Although there is no single mechanism responsible for the different gestational complications associated with maternal obesity, the available evidence would suggest that the main culprits are hyperinsulinaemia, resulting from increased pre-gestational insulin resistance, and pro-inflammatory state and oxidative stress, which would contribute to early placental dysfunction and effects on the foetus. The placenta of these pregnant women is characterised by increased weight, elevated lipid content and the accumulation of pro-inflammatory mediators, altered gene expression and functional abnormalities.4

Management of obesityPreconception periodThe preconception period is an ideal time to assess and manage conditions that may affect the health of the mother and foetus during the pregnancy, as they can have long-term implications for both.

Weight stigmaDuring the periconception period, women are particularly vulnerable to weight stigma, including in the healthcare setting, where some healthcare professionals may evince prejudice and negative attitudes towards them. This situation can directly affect their physical and mental health and quality of life.18 Education in the health sector through recommendations for maintaining positive communication is essential if this situation is to be improved, for example using person-first language, promoting healthy behaviours rather than focusing solely on weight, and involving obese women in the therapeutic decision-making process.19

The role of primary careRoutine Primary Care (PC) practice includes health promotion and prevention actions, and PC is often the first point of contact between the woman and her partner and the healthcare service before they conceive. Primary Care is therefore responsible for providing this new family with quality prenatal care with preventive activities prior to pregnancy. In relation to obesity, this situation provides the opportunity for effective communication with women and their families about weight goals at this stage of life, the importance of weight loss prior to pregnancy, maximum weight gain during pregnancy and postpartum weight loss in order to reduce the risk of adverse outcomes in current and future pregnancies. The ideal role of the PC doctor is to raise the woman's awareness of the importance of maintaining a healthy weight, help them to engage in effective weight loss strategies and to support any initiatives undertaken by the patient. In PC, the intervention strategy of the Five As (Ask, Advise, Agree, Assist and Arrange) has been adopted for the implementation of behavioural interventions and advice on the main risk factors, including weight control.20

Healthy weightThe guidelines recommend that women of childbearing age and BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2 should receive pre-pregnancy counselling about the risks associated with obesity for their health during pregnancy and that of their child, and even that women with a BMI ≥ 40 kg/m2 should be referred to a specialist centre in the pre-conception period.21 The goal should be weight reduction to achieve a BMI < 30 kg/m2 or ideally in the overweight or normal range. However, improvements have been found in both maternal and neonatal outcomes in these women with weight reductions of between 5% and 10% of their initial weight,22 so weight reduction should always be personalized.23

Lifestyle changesThe first line of treatment for tackling obesity consists of promoting healthy habits through lifestyle changes, which combine dietary interventions and physical exercise (PE).24 There is no single diet for promoting weight loss, so it is important to design a personalised plan taking the woman's characteristics and preferences into account. In general, healthy diets encourage the consumption of plant-based foods, rich in fibre, vitamins, minerals and antioxidants (vegetables, fruits, legumes and whole grains), and unsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts and oily fish), together with poultry, dairy products, eggs and red meat eaten in moderation. Eating patterns such as the Mediterranean diet (MD), Atlantic, vegetarian or low glycaemic index (GI) diets could be effective for weight loss.25

PE should be started gradually, aiming for 150 min of moderate-to-intense aerobic activity such as running, cycling, swimming, aquagym or dancing. In addition, programming strength activities, either with the body alone or using elastic bands, two or more times a week is recommended.

At the same time, cognitive-behavioural psychological support should be considered in order to facilitate adherence to changes and to keep them up.26

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis has shown that preconception lifestyle changes are also associated with less weight gain during pregnancy and with maternal-foetal benefits, with dietary intervention being the most beneficial strategy.14

During the peri-gestational stage, alcohol and tobacco, as well as any other toxic substances, should be completely avoided.

Nutritional deficienciesWomen with obesity are at greater risk of having nutritional deficiencies, hence advice should be given to optimise their nutritional status prior to conception, especially if they have had bariatric surgery (BS). High-dose folic acid supplementation of 5 mg/day is recommended during the pre-gestational stage (1−3 months) and the first trimester of pregnancy, as women with obesity are at higher risk of neural tube defects and have lower circulating concentrations of folic acid.21 Additional preconception supplementation of other micronutrients, such as iodine, iron and vitamin D, should be considered in this population in accordance with the recommendations of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) and The Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG), respectively.27

Control of comorbiditiesApart from addressing weight in women with obesity who wish to become pregnant, in pre-pregnancy clinics it is also important to optimise the control of obesity-related complications, such as hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus (DM2), dyslipidaemia and sleep apnoea and hypopnoea syndrome (SAHS), as this has a beneficial impact on maternal-foetal outcomes. According to the recommendations of societies such as the Canadian Society of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (SOGC), preconception screening in obese women should include kidney, liver and thyroid function tests, a cardiovascular risk assessment, which would include screening for diabetes, hypertension, lipid profile and an echocardiogram, plus pulmonary function tests (including a sleep apnoea study if there were compatible clinical symptoms).28 At the same time, all drugs contraindicated during pregnancy, including drugs for the treatment of obesity, should be discontinued before the woman becomes pregnant, since to date the effects on the foetus are unknown.20

Reviews on the subject have shown that women who receive pre-pregnancy or between-pregnancy counselling have higher folic acid intake, lower weight gain during pregnancy and greater postpartum weight loss in addition to a lower risk of both GD and of the newborn being small for their gestational age (SGA).22

Medical managementFrom the pharmacological standpoint, few studies have been published in this area because the guidelines recommend that any potentially teratogenic medical treatment be discontinued before pregnancy.20 Some studies have analysed the effect of GLP1 analogues a few weeks before conception. In one of these studies, greater weight loss and an increase in the rate of spontaneous pregnancies were found in a cohort of women with obesity and PCOS who received treatment with exenatide during a short pre-pregnancy period when compared with metformin.29 Another pilot study in a cohort of women with obesity and infertility due to PCOS compared short-term treatment preconception with low-dose liraglutide combined with metformin to treatment with metformin alone, observing an increased IVF pregnancy rate in the combined treatment group.30 There is also a retrospective study on the use of phentermine in the preconception period in a cohort of women with obesity and infertility which found an average weight reduction of about 5 kg in three months and a pregnancy achievement rate of 60%.31

Weight management in the preconception period may also include advice on surgical treatment for obesity prior to pregnancy. Women who are candidates for BS should be advised and assessed by a multidisciplinary team, highlighting the benefits of weight loss prior to pregnancy, not only in terms of fertility, but also in maternal-foetal complications, without forgetting the potential negative consequences for maternal health (nutritional deficiencies, mechanical complications with restrictive techniques, episodes of intestinal obstruction due to internal hernias or weight regain) and foetal health (SGA and intrauterine growth retardation), as well as the advisability of referral to a specialised centre for management during the pre-pregnancy, pregnancy and postpartum periods.32,33

During pregnancyGestational weight gainAlthough specific figures for gestational weight gain (GWG) are usually based on pre-pregnancy BMI,34 everything would seem to indicate that the woman's weight prior to conception is more important.35 Moreover, the GWG recommendations do not distinguish between different degrees of obesity, although they do establish a range of obstetric risk based on them,27 as shown in Table 1. These values are intended to improve the prognosis of the pregnancy, although it should be borne in mind that the figures are purely indicative. Weight control during pregnancy can have an effect on the pregnant woman's bond with the healthcare team, and the possible anxiety caused to her must be taken into account, hence the real need for routine weight control should be assessed at each visit.18

BMI range, suggested weight gain during pregnancy and risk of perinatal complications.

| Initial BMI (kg/m2) | Total gestational weight gain (Kg) | Risk of complications | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low weight | <18.5 | 12.5−18 | Increased |

| Normal weight | 18.5−24.9 | 11.5−18 | Low |

| Overweight | 25−29.9 | 7−11.5 | Increased |

| Class I obesity | 30−34.9 | 5−9 | High |

| Class II obesity | 35−39.9 | Very high | |

| Class III obesity | ≥40 | Extremely high |

a Food and Nutrition Board. Institute of Medicine, 2009.

Source: Rasmussen et al.34

The evidence suggests that lifestyle changes, such as following a healthy diet and regular physical exercise, improve maternal-foetal outcomes and prevent excessive weight gain during pregnancy,36,37 so this strategy should be encouraged and agreed to on a consensus base.

First of all, the pregnant woman should be asked about advice on lifestyle changes received during the pre-pregnancy period, and if they have been beneficial they should be encouraged to keep them up. Dietary changes should be adapted to the habits, preferences and possibilities of the pregnant woman. The efficacy of different dietary approaches (MD, low GI diet) adapted to the gestational period has been demonstrated.38 Regular PE during pregnancy has been shown to be safe, in addition to providing multiple benefits. Gestational age and individual needs and abilities should be taken into account to gradually increase exercise and should include moderate-intensity aerobic activity, such as walking, swimming, stationary cycling, yoga or pilates and low-impact strength exercises.39

Management of associated comorbidityFor the reasons described above and the technical difficulties that may arise in performing obstetric ultrasounds, pregnant women with severe obesity (classes 2 and 3) should be referred to a specialised centre to minimise risks. The clinical guidelines establish a series of recommendations in this regard28:

- 1

GD screening is suggested in the first trimester (2-step method in our setting) given the importance of blood glucose control in early foetal development. If negative, it should be repeated between weeks 24 and 28 of gestation, as in the general population.

- 2

For proper blood pressure measuring, the size of the sphygmomanometer cuff must be considered; it must be adequate for the diameter of the patient's arm and should be at least 80% of the length of the arm (measured as the distance from the acromion process to the olecranon process) and 40% of its width.

- 3

Prophylaxis with acetylsalicylic acid should be considered in class II or morbid obesity based on risk factors for hypertensive complications of pregnancy.

- 4

Thromboprophylaxis with low molecular weight heparin is suggested during pregnancy in patients with obesity and two more risk factors (1 if obesity is class III or higher). In class III obesity and in obesity with another added risk factor, thromboprophylaxis and compression stockings for 10 days after delivery should be considered.

- 5

SAHS screening is recommended, based on medical history and the anaesthetic assessment of women with class III obesity before delivery.

- 6

Vitamin D supplementation is a subject of debate. Some guidelines do not recommend it, others recommend supplementing all pregnant women with 400 IU daily of vitamin D, while others give indications of daily intake as high as 1500–2000 IU. Although some studies suggest improved maternal and foetal outcomes after vitamin D supplementation, vitamin D supplementation is not recommended for obtaining extra-skeletal benefits.40

Induction of labour at 41 weeks of gestation should be considered due to the increased risk of intrauterine foetal death.

Pregnancy after bariatric surgeryMany patients who have had BS continue to have some degree of obesity after the surgery, so all the above recommendations need to be taken into account in the case of pregnancy. Multidisciplinary follow-up of these women during pregnancy is also advisable. Particularly in these pregnant women, the following are recommended41:

- 1

Avoid pregnancy until 12 months after the BS to wait for the weight stabilisation phase.

- 2

Assess possible micronutrient deficiencies before pregnancy and in each trimester (at least blood count, iron, ferritin, folate, cobalamin, calcium and vitamin D) and recommend a specific multivitamin for pregnancy in addition to the specific supplements appropriate in each case. Although the level of evidence is low (level 4), the daily supplementation shown in Table 2 is suggested.

Table 2.Recommended daily supplementation for pregnancy complicated by bariatric surgery.

Thiamine >12 mg Folic acid 5 mg Vitamin B12 1 mg (or 1 mg intramuscular every 1−3 months) Calcium 1200−1500 mg (including dietary intake) Vitamin D > 40 µg (1000 IU) Elemental iron 45−60 mg Copper 2 mg Zinc 15 mg Selenium 50 µg Vitamin E 15 mg Vitamin A 5000 IU (such as beta-carotene) Vitamin K 90−120 µg Source: Shawe et al.41

- 3

Perform baseline blood glucose and HbA1c tests in the first trimester to rule out frank diabetes of pregnancy. Screening for GD should be performed with capillary blood glucose measurements before and after meals for one week between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation. If >20% of blood glucose measurements exceed the cut-off points (≥95 mg/dl fasting or preprandial, ≥140 mg/dl 1 h post-intake and ≥120 mg/dl 2 h post-intake), a diagnosis of GD would be considered.

- 4

Monthly foetal ultrasound monitoring from 28 weeks of gestation to monitor foetal growth, given that BS increases the risk of newborns SGA.

Most women with GD return to a normoglycaemic state immediately after delivery. However, they have a risk of recurrence of GD in subsequent pregnancies of around 50%, especially those with a higher BMI and a birth weight of the previous child of more than 4 kg.42 They also have a 10 times higher long-term risk of developing DM2 than women without previous GD, the risk factors being BMI before and after pregnancy, maternal age, a family history of DM, basal blood glucose values in pregnancy and the need for insulin treatment during pregnancy.43 For these reasons, reassessing the metabolic status of patients who have had GD is recommended at 4–12 weeks postpartum with the 75 g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) using the diagnostic criteria for the general population.44 In the case of women with obesity and glucose intolerance or impaired basal glucose, an annual check-up is recommended, including complete somatometry (BMI and waist circumference), blood pressure and laboratory tests with basal glucose, HbA1c and lipid profile. GD is associated with twice the risk of developing metabolic syndrome and non-alcoholic fatty liver and a two-fold higher risk of cardiovascular disease in the first decade after childbirth, compared to women without GD.45

Postpartum weight retentionIt is estimated that a year after giving birth over 20% of women retain more than 5 kg.38 Significant postpartum weight retention (PPWR) is associated with obesity, diabetes and heart disease in the long term, so it is advisable to minimise the risks when planning a future pregnancy.46 PPWR is also associated with an increased risk of complications in a subsequent pregnancy regardless of the initial BMI.47

Lifestyle changesIn the postpartum period, the advice is to maintain healthy habits through a balanced diet and regular PE with the aim of reversing weight gain and improving metabolic profile. There is no consensus on the optimal time to involve mothers in postpartum weight control, but interventions on lifestyle changes have demonstrated their effectiveness, with a positive correlation the more intensive the intervention.38

BreastfeedingWomen with obesity are almost half as likely as women with normal weight to start and continue breastfeeding (BF).48 BF should be encouraged, since among many other benefits in the mother-baby dyad it is associated with greater weight loss during the puerperium. Supporting BF with activities targeting mothers with obesity during and after pregnancy as part of promoting healthy habits will contribute to improving women's physical and mental health. Moreover, promoting BF may be particularly relevant in this population due to its beneficial effects on child health, which is more vulnerable to cardiovascular and metabolic problems in the future as a consequence of maternal obesity problems.

Perinatal mental healthAn estimated 15% of women will have a mental disorder during the perinatal period. The most common disorder is postpartum depression, with a prevalence of around 10%.49 Obesity is a risk factor for the development of depressive disorders during the perinatal period, and prevalence seems to increase with the degree of obesity.50 This situation causes maternal suffering with symptoms of anxiety, loss of control or stress, which can lead to a lack of self-care, failure to attend prenatal check-ups, non-adherence to treatment and abuse of toxic substances, also compromising the newborn's health. Treatment requires a multidisciplinary intervention for the design and application of a personalised plan based on scientific evidence and maternal needs.

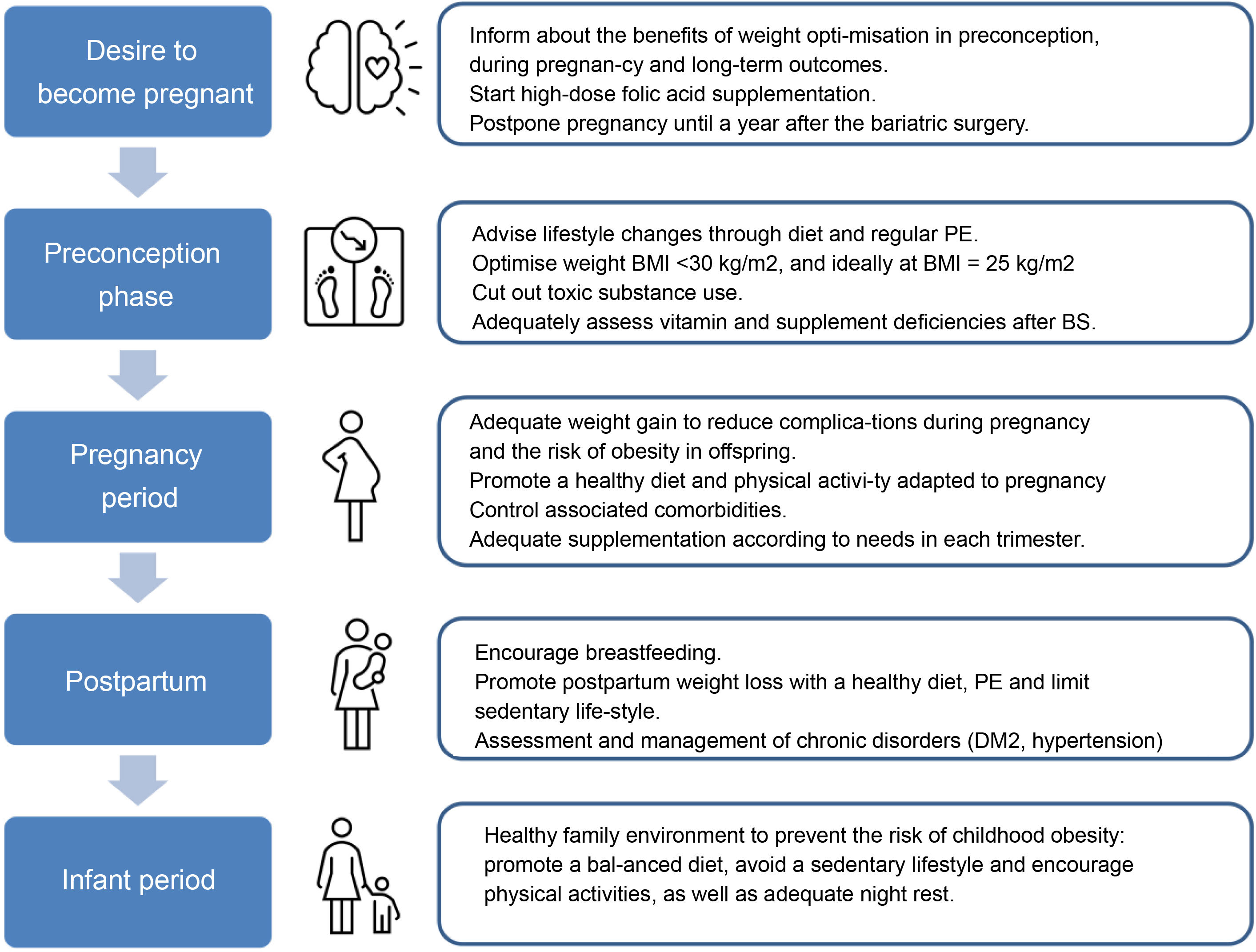

ConclusionsThe available evidence collected in this review supports the implementation of strategies for the prevention and integrated management of obesity in women of childbearing age, with the aim of improving their fertility, reducing pregnancy-related risks and benefiting the health of their offspring. Population-based information-providing activities, the design and development of preventive and therapeutic programmes and specific training for the different healthcare professionals involved in the management of these patients are all necessary, in addition to the organisation of multidisciplinary teams for the most complex cases. The involvement of the health authorities and scientific societies is essential for the organisation of activities intended to promote research, training and dissemination of information, in scientific forums and in the media, social networks, health centres and other areas in order to address a highly-prevalent problem, and at the same time potentially improve the health of the population (Fig. 1).